The Role of Plant Agricultural Practices on Development of Antimicrobial Resistant Fungi Affecting Human Health: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 10 Integrated Plant Disease Management

10

Integrated Plant Disease Management

The ninth session of the workshop focused on agricultural technologies and strategies to mitigate the threat of antifungal resistance by reducing the use of fungicides and addressing conditions that foster development of resistant fungi. Tim Widmer, national program leader for plant health at the U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service (USDA/ARS), moderated the session. Melanie Lewis Ivey, associate professor of plant pathology at The Ohio State University (OSU), discussed technology that reduces fungicide output, decreases water usage, and yields financial savings while also being as effective as traditional fungicide application methods in controlling disease. Walt Mahaffee, research plant pathologist at the USDA/ARS, detailed challenges in detecting grape powdery mildew, new detection methods, and efforts to detect azole resistance in this fungus. Jianhua Zhang, evolutionary microbiologist at the Netherlands National Institute for Health and Environment, discussed dynamics of A. fumigatus hotspots and strategies to decrease the total number of A. fumigatus or remove the fungicide pressure to select for resistance within these settings.

Widmer noted concerns expressed by multiple workshop participants regarding the possible connection between agricultural application of azoles and resistant pathogens in humans, as well as the challenges in verifying and communicating that connection. Regardless of a relationship between agricultural fungicide use and human pathology, more judicial and reduced use of fungicides is advantageous for plant health and thereby for growers, by decreasing the likelihood that the target pathogen will develop resistance. Therefore, an integrated disease approach could reduce resistance-induced

pressure on the plant pathogen, which, in turn, could potentially lead to a reduction of resistance in human pathogens.

PRECISION APPLICATION TECHNOLOGIES AND STAKEHOLDER COMMUNICATION

Ivey discussed technology designed to reduce chemical use, resulting in decreased volume of fungicide application within the environment and savings in cost and water usage. She detailed validation measures used to demonstrate that this technology offers spray coverage and disease control equivalent to that of traditional fungicide application methods. Ivey is a fruit pathologist who works to identify economical and sustainable strategies to control diseases of fruit, hop, and nut crops, with a particularly focus on reduced reliance on pesticides, pesticide resistance mitigation, and pesticide stewardship.

Laser Guided Intelligent Sprayer Technology

Ivey described how fruit crops are sprayed using airblast technology, which creates a huge plume of pesticide; some of the pesticide settles on the crop, but the majority goes into the air or drops to the ground. Heping Zhu, a professor in the department of Food, Agricultural and Biological Engineering at OSU and agricultural engineer at USDA/ARS, approached Ivey in 2016 to determine whether a laser-guided intelligent sprayer he had developed for the ornamental industry could be used in the fruit crop industry. Using lidar sensor technology, the sprayer can detect the canopy architecture and density, as well as measure the speed at which a tractor is traveling. The sprayer collects these measurements as it moves along a row of crops, using these data to determine the quantity and location of nozzles to engage and the variable spray pressure setting appropriate for the density of the canopy. Whereas conventional airblast technology sprays continuously as it travels each row of crops, the intelligent sprayer utilizes a pulsating spray pattern; it issues spray as it detects plants, and it ceases to spray as it detects the spaces and posts in between plants. Similarly, the sprayer only engages the nozzles required to treat the specific height of each plant. This technology results in reduced drift during application.

Technology Efficacy Validation

During initial tests of the intelligent sprayer, growers expressed doubt that the chemicals were coming into contact with the plants due to the low levels of product being used and the lack of visible droplets, said Ivey. Traditional airblast technology utilized since the 1950s produces a spray

that is visible on plants, on farmers themselves, and in the drift in the air. Thus, validation efforts became a component of stakeholder communication. Validation criteria included (1) provision of adequate coverage for pest control, (2) provision of disease control equivalent to airblast technology, and (3) economic and environmental sustainability. Ivey remarked that in the fruit crop industry, environmental and economic sustainability are associated, because growers can increase market share by labeling products as “reduced pesticide” or “pesticide free” without meeting organic status.

Adequate Coverage and Disease Control

Optimal spray coverage for pest control purposes is 25–30 percent, with coverage below 25 percent deemed inadequate and greater than 50 percent considered excessive, Ivey explained. Excessive spray coverage indicates that greater quantities of pesticides are being applied than what is required to control pests. To test the spray coverage of the intelligent sprayer, water sensitive cards were attached to apple trees and grape plants. Samples were taken from various locations of the plant canopy and trunk or vine for both the intelligent mode and the airblast mode. The pesticide coverage of the intelligent sprayer measured between 42–56 percent, with the center of the plant indicating higher percentage coverage than the samples taken from the edge of the canopy. In comparison, the pesticide coverage with the airblast sprayer was 61–79 percent, with samples from all parts of the plant surpassing the 50 percent threshold for excessive coverage. The mean percentage for all intelligent sprayer samples was 50 percent, compared to a mean of 70 percent for the airblast method. To validate adequate disease control, grape plants were investigated for foliar fungal diseases including powdery mildew, downy mildew, and black rot. The same fungicide program was utilized for the crops treated by the intelligent sprayer and the crops receiving airblast application. The two types of sprayers demonstrated similar percentages of disease severity and progression, which were significantly better than the non-treated control group. This finding indicates equivalent disease control for the intelligent and airblast sprayers, said Ivey.

Environmental and Ecological Sustainability

Pesticide volume and water usage are equivalent, and pesticide volume output was measured to determine water usage for the two application methods, Ivey explained. Measurements were taken for grape plant application at various phenological stages. When grape plants are small, they feature a larger ratio of trunk to green growth. As they become larger, the canopy expands. The intelligent sprayer moves between rows of plants and applies pesticide when it senses canopy or trunk. Therefore, as plants have

wider canopies, pesticide is applied a greater proportion of time, and the pesticide volume output increases. The intelligent sprayer pesticide output for plants at 10–12 inches of growth on the grape vine was less that 0.2 liters per vine. This rate increased with plant size until reaching a rate of approximately 0.7 liters per vine for grape at pre-harvest stage. In contrast, the airblast pesticide output is fairly consistent across all phenological stages, measuring between 0.7 to just over 1 liter per vine for all stages. Depending on the phenological stage, the intelligent sprayer demonstrated a 29–91 percent reduction in pesticide and water usage over the airblast technology. Thus, the intelligent sprayer achieves equivalent disease control as the airblast, while using far less water and releasing smaller quantities of pesticide into the environment.

Ivey emphasized that California is experiencing drought to the extent that farmers with minimal access to water must drive miles to refill water tanks. This reduction in water usage would necessitate fewer trips for water for farmers using the intelligent sprayer. She added that the results were validated in an apple orchard. The farmer conducting the pesticide application for the demonstration trial decided to use the new technology on the remainder of his 100-acre orchard due to the reduction in chemical and water usage. The reduced pesticide output translates to financial savings, with the pesticide cost dropping $469 per hectare when using the intelligent sprayer. Ivey noted that this figure is a 3-year average of the same chemical program used each year based on 2019 prices. The price of fungicides has since skyrocketed, and this price increase could alter the reduction in cost.

To validate the economic sustainability of the intelligent sprayer, Guilherme Signorini, assistant professor of value chain management in the Department of Horticulture and Crop Science at OSU, conducted a cost-benefit analysis of utilization of the new technology in a 20-hectare vineyard. The analysis assumed that investment is made in year 0, the plants require 3 years to produce grapes, and the vines will have 23 years of productivity in a viniferous planting. Fixed and variable costs were based on an enterprise budget Signorini developed, and extreme weather conditions and grape cost were excluded from the analysis. Ivey noted that the cost of the intelligent sprayer is considerable, and her figures are based on the price after Heping sold the technology to a sprayer company. Demand for the intelligent sprayer has been high, and thus the current cost may have increased since the analysis was last updated before being submitted for publication. At the time of this analysis, a new intelligent sprayer costs $70,000. Retrofitting an existing sprayer with the intelligent technology is approximately $36,000. Whereas an intelligent sprayer purchased in new condition decreases in value over time, with a net present value of under $50,000, the present value of a retrofitted sprayer is over $51,000, indicating an increase in value. The internal rate of return is comparable for both

the new and retrofitted sprayers, at 14.3 and 14.8 percent, respectively. Similarly, the payback terms are nearly equivalent at 11.7 years for the new sprayer and 11.4 years for the retrofitted. The return on investment is 3.53 for a new machine and 4.45 for a retrofitted one. Ivey noted that an economic analysis is currently being conducted for an apple orchard, and the payback term will likely be about half the length of the grape vineyard setting.

Ivey remarked that the intelligent sprayer provides environmental benefit by achieving reduced pesticide and water usage, which is particularly valuable as extended droughts become more frequent across the United States. Targeted pesticide applications decrease the pesticide in the ground and air, resulting in less contact with non-target organisms. She added that the growers involved in the demonstration trials have become promoters of the intelligent sprayer, suggesting that farmers would be open to adopting this new technology.

FINDING NEEDLES IN HAYSTACKS: DISEASE MONITORING AND RISK ASSESSMENT

Mahaffee gave an overview of fungal disease management, challenges in detecting grape powdery mildew, recently developed detection methods involving samples from the air and from field workers’ gloves, and efforts to detect azole-resistant powdery mildew. Grape production within the United States has a farm gate value of $6 billion, and it has an economic impact of almost $220 billion in grape-producing regions. Mahaffee described that 95 percent of grape yield is attributed to fungicide-based disease management of grape powdery mildew (Gianessi and Reigner, 2006). Thus, 78 percent of pesticide used in grape production targets this pathogen (Fuller et al., 2014).

Fungal Disease Management

Because disease will inevitably develop in an agricultural crop, the goal of disease control is to delay that development to limit economic impact, Mahaffee remarked. Disease control works toward the aim of pushing the logistic curve of a disease further into the future. The threat from any given plant pathogen varies annually, posing high risk during some years and low risk during others. No single tool addresses all threats. Rather, successful disease management involves combining tools in the locations, times, and sequences that are most effective. These tools include pesticide application, disease forecasting, disease scouting, and cultural practices related to fertility, canopy management, and planting times. Mahaffee noted that he has seen the frequency of fungicide applications for grape

powdery mildew range from 3–17 applications per year. The majority of fungicide compounds only affect the infection process—rather than curing established disease—and therefore most fungicide applications are primarily prophylactic. Pesticide product labels specify regulatory stipulations regarding the frequency of use, rotation, and other products with which a compound can be mixed within a single application.

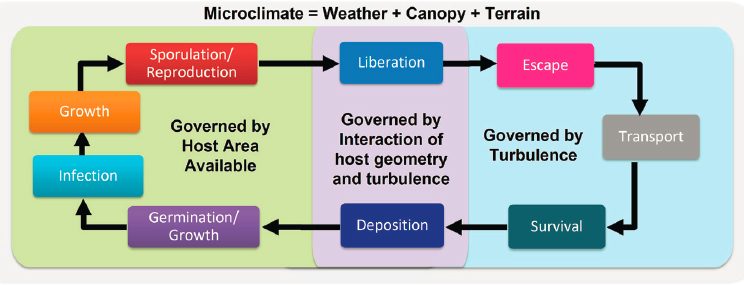

Crop disease risk is not uniform nor random across the field. Identifying a localized approach to replace broadcast fungicide application is challenging due to the difficulty in detecting and locating powdery mildew. Detection tools for the fungus are limited to spectral data and visual observation, and powdery mildew must be identified within a small portion of the pathogen life cycle in order to be controlled (Aylor, 2017). Visual observation often results in false positives, and visual scouting data Mahaffee collected indicate that the percentage of false positives sometimes exceeds the percentage of incidence during an observation period. To improve pathogen monitoring, Mahaffee and his team have investigated mechanisms for detecting spores during the dispersion segment of the pathogen life cycle, while they are still in the air and have not yet attached to hosts (Mahaffee et al., 2023) (see Figure 10-1). Various types of mobile spore trap detection devices have been deployed for this purpose.

Inoculum Detection

Mahaffee has engaged in research on using inoculum detection to inform fungicide intervals (Thiessen et al., 2016, 2017, 2018). In the initial phase of this research, fungicide application was based on pathogen detection in the air using spore traps. The application intervals were then adjusted based on pathogen concentration. Over an interval of eight field

SOURCE: Mahaffee presentation, June 27, 2022; Mahaffee et al., 2023.

seasons, fungicide frequency was reduced by an average of 3.8 applications per season, resulting in a decrease of over 13 pounds of fungicide per acre. This reduction equated to a cost savings of $150–250 per acre in fungicide costs, depending on the chemicals being used. He and his colleagues are working with several companies to commercially implement this method. In collaboration with Rob Stoll at University of Utah and Brian Bailey at University of California, Davis, his team is using modeling to develop a rational strategy for deployment of inoculum samplers.

Powdery mildew does not become visually detectable until the leaf is at least 5 percent infected, Mahaffee noted, highlighting the difficulty of detecting pathogens on plants. At that point, even the most intense scouting efforts have less than a 50 percent probability of detecting disease. Sarah Lowder, a doctoral student of plant pathology at Oregon State University, conducted research using swabs of vineyard workers’ gloves as a method for monitoring disease and fungicide resistance risk. Given that workers interact with the plants, she investigated whether pathogens could be identified by sampling workers’ gloves. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis found that visual detection methods resulted in a high number of false negatives. The glove sampling detected pathogens at lower levels before they became visible. The study found that disease can be detected almost a month earlier using the glove sampling technique over visual observation.

Resistance Detection

In addition to pathogen detection, the spore trap and glove swab techniques have been used to test for quinone outside inhibitor (QoI) resistance (Miles et al., 2021). The G143A allele associated with QoI resistance began appearing in field populations in 2013 and prevalence steadily progressed until 2016, when major disease control failure events took place across much of the Western United States. In 2017, Mahaffee and colleagues worked with growers to cease use of QoI fungicides, and the frequency of the resistant allele decreased as QoI usage was reduced. From 2018–2020, nearly 5,000 samples from 107 vineyards in 17 West Coast counties were tested for QoI resistance. A higher frequency of resistance was found in California than in Oregon or Washington, but California also has a higher density of grape production. Therefore, it has not been determined whether the resistance is related to the density of production, given that spores can travel from one vineyard to another neighboring one. A public database enables growers to view the frequency of QoI resistance detection in near-real time.1

___________________

1 The Fungicide Resistance Assessment, Mitigation and Extension (FRAME) Network database is available at https://framenetworks.wsu.edu (accessed August 29, 2022).

Research is under way to detect azole resistance in grape powdery mildew, which is associated with the Y136F mutation (Golan and Pringle, 2017). Approximately 4,000 historical air samples collected from conventional and organic vineyards throughout the season were investigated, confirming the Y136F mutation in 273 of the samples. These samples with Y136F mutation were then tested for the TR34 and TR46 alleles associated with azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus (A. fumigatus), but A. fumigatus was not identified within the samples. However, Botrytis cinerea—a fungus similar in spore morphology and size to A. fumigatus—was detected in all samples. Mahaffee expressed that the detection of Botrytis cinerea indicates that the DNA collection technique was suitable for isolating A. fumigatus DNA. Mahaffee is researching whether sentinel data can be used to determine the probable source of an inoculum plume and predict the area at risk for deposition and disease development.

MITIGATION MEASURES IN COMPOST HOTSPOTS

Zhang discussed features of A. fumigatus hotspots—settings in which resistant fungi proliferate—and strategies to transform these into coldspots by reducing the total number of A. fumigatus or removing the fungicide pressure that selects for resistance. In 2015, she discovered that samples taken from flower bulb plant waste heaps contained high numbers of azole-resistant genotypes (Zhang et al., 2017a). Research revealed that these heaps also contained substantial amounts of fungicide residues. At the time, she worked at the Wageningen University and Research, and she found that a plant waste heap located near the institution had low levels of azole residues and azole-resistant fungal isolates. This sparked her investigation into why some plant waste heaps become resistance hotspots.

Dynamics of Azole-Resistance in Hotspots

Zhang tested numerous potential types of natural waste for A. fumigatus. Flower bulb compost, wood chippings, and green waste were all determined to be hotspots for the fungus (Schoustra et al., 2019a,b; Zhang et al., 2021c). She noted that fruit waste, silage cow feed, wood waste, grain storage, and manure and straw from chickens and cows were not found to have substantial levels of A. fumigatus. The process of composting bulb waste was explored in order to determine the portion(s) of the chain during which A. fumigatus developed resistance. Composting begins during summer harvest, with a small pile of bulb plant leaves that becomes larger as more waste is discarded. Multiple processes are at play as pre-compost degrades into mature compost—such as explosive growth of bacteria and fungi and increases in temperature from less than 40 degrees

Celsius to 65 degrees—which enable the compost to kill plant pathogens (van der Wurff et al., 2016).2 Approximately 3–4 months into the composting process, machinery is used to turn the piles on a bi-weekly basis until the compost reaches maturity, at which point it is used in planting new crops of flowers. Zhang found that the practice of turning the compost piles releases clouds of spores into the air.

Samples from the flower waste heaps were taken over the course of a year to determine whether emergence of resistant A. fumigatus is dependent on the season or stage of the operation (Zhang et al., 2021c). The heaps were tested for total amount of A. fumigatus, concentration of azole fungicides, and fraction of resistant isolates compared with the total population. A. fumigatus was found throughout the year, independent of the season, whereas azole fungicide concentration varied over time. The samples indicated a high fraction of resistant isolates in the population with initial readings of approximately 50 percent. Zhang described challenges in isolating A. fumigatus in the samples arising from the presence of other fungi that were difficult to remove from the culture plates. She and her team developed a new “flamingo” medium—so named for its pink color—which resulted in better A. fumigatus isolation over five other media (Zhang et al., 2021a). The flamingo medium resulted in significant reductions in surface area covered by non-A. fumigatus in plant waste samples, as well as in samples from ditchwater, grass, soil, and wood.

Once the A. fumigatus was isolated, seven types of resistant genotypes were identified, all of which contained TR34 and TR46 mutations (Zhang et al., 2021c). Zhang noted that the dominant genotype varied over time. During the course of a year, resistant genotypes appeared and remained present for variable durations, with some genotypes no longer detectable 1 month after appearing, while other genotypes remained present for multiple months. She described that the cyp51A gene involved in azole resistance has evolved over time. The first identified clinical azole-resistant isolate—TR34/L98H—appeared in 1998 (Snelders et al., 2012). In the years since, TR34/L98H has been found in bulb waste heaps, in addition to additional resistant cyp51A genotypes that have emerged. With these genotypes, both the length of the promoter region and the variation and single nucleotide polymorphism mutation have increased over time.

Flower bulb waste material has been found to be a natural niche for the sexual cycle in A. fumigatus (Zhang et al., 2021d). In researching how bulb waste heaps promote sexual reproduction of A. fumigatus, Zhang found that this substrate provides favorable conditions for reproduction, including adequate nutrition, a dark environment, and 30-degree Celsius temperature.

___________________

2 More information about compost research conducted at Wageningen University and Research is available at www.biogreenhouse.org (accessed August 30, 2022).

Furthermore, sexual reproduction promotes the survival of A. fumigatus in the flower bulb waste, because ascospores produced during this process withstand extreme conditions (Zhang et al., 2015, 2021b). Sexual reproduction also can generate diverse genotypes able to survive varying conditions. When the spore begins to grow and undergoes mitotic division, de novo mutations can occur. In the presence of azole fungicide residue, a resistant genotype can be selected over time. Thus, the sexual cycle and sporulation of A. fumigatus are important functions for adaptation within the waste heaps.

Zhang explained that 1 gram of bulb waste compost can contain 100,000 A. fumigatus spores. Moreover, a single stockpile measuring 50 meters wide by 50 meters long and 10 meters high may contain 2,500,000,000,000,000 A. fumigatus spores, half of which could be azole-resistant, given a 50 percent abundance approximation. Furthermore, these resistant spores can involve various genotypes resulting from asexual and sexual reproduction and azole selection.

Strategies to Mitigate Resistant A. fumigatus

The development of bulb plant waste composting offers ecological benefits. In the 1970s, plant waste in Europe was burned, releasing carbon dioxide into the air that contributed to climate change. Zhang noted that many developing countries continue to burn plant waste on large scales. Although the circular economy of reusing plant waste to fertilize future crops offers ecological sustainability, it generates enormous quantities of resistant A. fumigatus spores, which can pose health risks to susceptible patients. Thus, approaches that balance both ecological and health needs should be considered. Strategies to alter the plant waste stream to transform hotspots into coldspots are being investigated in an effort to capitalize on the ecological benefits of composting without increasing health threats. Wageningen University and Research is conducting ongoing studies on self-composting and compost fermentation processes to determine whether these methods can reduce the total number of A. fumigatus spores or remove the selective pressure of azoles. They are experimenting under controlled conditions toward understanding the factors that can reduce A. fumigatus and the pressure of azoles; they plan to apply these learnings in validating strategies within the agricultural setting.

A strategy to reduce the total number of A. fumigatus spores involves interrupting its propagation and germination processes. Waste plant material is put into boxes that vary in substance and conditions. Given that different conditions can influence the growth of A. fumigatus, Zhang stated that it may be possible to identify conditions that reduce A. fumigatus growth. Freestanding plant waste piles were compared with plant waste placed in wooden boxes, plastic boxes, and plastic boxes with water added.

Preliminary data found prolific growth of A. fumigatus in wooden boxes and significant reduction of A. fumigatus in non-watered plastic boxes. Although the plant waste in watered plastic boxes had more A. fumigatus than the freestanding piles, the percentage of resistant isolates was lower in the watered boxes. These findings demonstrate that oxygen and water content could play a role in reducing A. fumigatus, said Zhang. Studies are also exploring whether adjusting the ratio of bacteria, yeast, and mold in compost can reduce the amount of A. fumigatus in compost. Bacteria are being added to plant waste to determine whether (1) the compost ecosystem will still function with an adjusted ratio and (2) A. fumigatus will remain at a lower proportion.

Zhang described another approach to transforming hotspots involving removal of fungicide pressure and selection. Fungicide residues constitute a source of carbon and nitrogen, and microorganisms could potentially degrade these residues. A laboratory study found that Pseudomonas aeruginosa can biodegrade propiconazole, a fungicide often found in agricultural plant waste (Satapute and Kaliwal, 2016). If Pseudomonas or a similar organism can degrade triazoles in agricultural settings, this strategy could reduce the fungicide pressure that causes A. fumigatus to select for resistance.

Plant waste is an excellent niche for A. fumigatus to complete its life cycle, evolve, and cope with extreme conditions. Zhang noted that much has been learned about hotspots, but the factor(s) driving the emergence of the TR genotype has not yet been identified. Collaboration is needed to determine the most effective strategies to mitigate azole resistance in A. fumigatus.

DISCUSSION

Jeff LeJeune, food safety officer in the Food Systems and Food Safety Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, asked whether integrated pest management (IPM) or other approaches can prevent the use of fungicides by reducing the need for it, particularly in low-income settings. Mahaffee replied that pathogens can evolve quickly—slowing this evolution to overcome resistance requires the incorporation of fungicides into the disease management program. Thus, IPM minimizes the use of fungicides to levels that are necessary to achieve desired outcomes, but this approach does not eliminate the need for fungicides. He added that a pesticide can be targeted to the stage of the pathosystem where it will have the most effect. For instance, in grape production, this often involves using sulfur fungicides early and limiting synthetic fungicides to the susceptible period during bloom, when maintaining crop quality is most critical. Ivey added that education and outreach efforts in low-income settings could

contribute to ensuring that pesticides are used correctly. The misuse of pesticides in terms of the number of applications used is common, thus education in this area is important in reducing use and mitigating resistance. Widmer remarked that social scientists can play a role in plant pathology by facilitating buy-in among growers to incorporate practices that limit fungicide use. Ivey noted that adopting new technologies poses challenges for mid-size growers. However, sustainability grants for new equipment could be established for farmers working to reduce the input of pesticides and increase environmental sustainability.

REFLECTIONS ON DAY THREE

Paige Waterman, interim chair of medicine and vice chair for clinical research at the F. Edward Herbert School of Medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, offered reflections on the third day of the workshop. The sessions highlighted the value of stepping outside of professional comfort zones, whether these be surveillance, diagnostics, therapeutics, mitigation, product development, laboratory research, agricultural environments, clinical settings, or policy arenas. Addressing antifungal resistance is an ongoing endeavor, and this workshop emphasized priority areas in bridging the gap between plant agriculture and human health. She noted her appreciation of the integrated approach the workshop utilized in examining the complexities involved in antifungal resistance.