Applying Neurobiological Insights on Stress to Foster Resilience Across Life Stages: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 6 Public Health and Clinical Strategies to Enhance Resilience

6

Public Health and Clinical Strategies to Enhance Resilience

Highlights

- Although often overlooked in traditional stress research, positive experiences and human adaptability play an important role in resilience-building, and exploring mechanisms that both reduce the impact of negative experiences and enhance responsiveness to positive ones might offer greater insight into human functioning and adaptability. (Fuligni)

- Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) constitute a public health crisis with immense societal costs. Expanding treatment access to individuals at high risk of having a toxic stress physiology with an ACE score of four or more regardless of mental health diagnosis has demonstrated improved access to care, quality of care, and outcomes along with potentially significant cost saving compared to traditional reactive care models. (Burke Harris)

- Longitudinal studies reveal that chronic exposure to racial discrimination, economic instability, and neighborhood disadvantage accelerates aging and increases disease susceptibility, disproportionately affecting Black communities and contributing to rising suicide rates among Black youth. Equipping parents with cultural strategies that foster racial pride not only reduces depressive symptoms in youth but also recalibrates neural

- responses that can collectively strengthen lifelong resilience. (McBride Murry)

- Despite the complexity of symptoms observed in children who have experienced abuse and neglect, a thorough holistic assessment can lead to clear, focused, and personalized treatment pathways that are effective and responsive to each child’s unique circumstances. (Minnis)

- Families can play a key role in protecting their children from the negative consequences of adversity, but masking underlying physiological stress can lead to onset of early aging. As such, there is a need for broader structural-level interventions beyond family, individual, and community support to alleviate the hidden mental, behavioral, and physical health burdens of discrimination and poverty. (Burke Harris, McBride Murry)

- While adverse experiences pose risks, many individuals have the capacity to adapt when provided with proper support. Reframing trauma as a challenge rather than an inevitable determinant of negative outcomes fosters empowerment and allows affected individuals to develop resilience through structured interventions and relational networks. (Burke Harris, Minnis)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Andrew Fuligni referenced Huda Akil’s discussion on the rise of mental distress among young people, suggesting that increasing stress levels may be worsened by a diminished emphasis on positive experiences, fewer opportunities for meaningful engagement, or an underutilization of neural systems designed to respond to such experiences. He proposed that as negativity escalates, access to enriching and supportive experiences may decline, further compounding the issue. Fuligni encouraged deeper exploration into mechanisms that not only mitigate the effects of negative experiences but also actively enhance responsiveness to positive ones. He also underscored the importance of resilience-building systems linked to positive experiences and human adaptability—elements often overlooked in traditional discussions of stress. This chapter, therefore, centers on the application of biological and

clinical insights into stress and resilience to strengthen public health strategies in intervention, prevention, and the detection of stress-related effects.

EVIDENCE-BASED MECHANISMS FOR EARLY INTERVENTION AND PUBLIC AWARENESS

Nadine Burke Harris discussed the profound public health implications of ACEs and toxic stress, framing these issues as a pressing public health crisis. She highlighted that two-thirds of the population have at least one ACE, but these experiences are disproportionately distributed among marginalized communities (Merrick et al., 2019). The term ACE originates from a landmark study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente over two decades ago (Felitti et al., 1998). The study identified 10 key categories of stressful or traumatic childhood events (see Figure 6-1). ACEs are preventable, potentially traumatic experiences that occur before the age of 18 and are linked to a wide range of negative health outcomes. Understanding these categories helps inform prevention and intervention strategies aimed at reducing their long-term impact. Burke Harris’s discussion elaborated on the dose-response relationships observed between ACE exposure and a range of adverse outcomes, with the greatest health risk associated with four or more ACEs (Putnam et al., 2013). These include associations with mental health conditions, substance use, homelessness, childhood adversity, and even links with the 10 leading causes of death.1

The CDC recently published a study estimating the annual economic burden of ACEs in the United States at approximately $14.1 trillion in direct health care costs and lost productivity (Peterson et al., 2023). Recognizing the scale of this impact, discussions have increasingly centered on the need to understand the biology of adversity to inform targeted public health strategies. Burke Harris reflected on earlier workshop discussions about how the biological effects of early life stress extend across multiple systems, such as the epigenetic, inflammatory, and endocrine pathways. Key disruptions include alterations in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, alongside impacts on critical brain regions such as the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and the ventral tegmental area involved in reward processing. Burke Harris also noted that there is an increasing amount of evidence that stress can be treated (Bick et al., 2015; Chino and Debruyn, 2006; Miller et al., 2014).

___________________

1 According to the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, the leading causes of death in the United States in 2022 included heart disease, cancer, accidents (unintentional injuries), COVID-19, stroke (cerebrovascular diseases), chronic lower respiratory diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, nephritis (including nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis), and chronic liver disease and cirrhosis (Kochanek et al., 2022).

NOTE: ACEs, identified in a CDC–Kaiser Permanente study, refer to 10 types of traumatic childhood events in three categories: Abuse (physical, emotional, or sexual); neglect (physical or emotional); and household dysfunction (parental incarceration, mental illness, substance dependence, divorce, or intimate partner violence).

SOURCES: Presented by Nadine Burke Harris on March 25, 2025; adapted from the Office of the California Surgeon General, 2025.

Burke Harris shared her efforts in helping to launch California’s Initiative to Advance Precision Medicine, a groundbreaking first-in-the-nation effort in toxic stress research, by focusing on the early detection of adversity’s effects on brain, immune, hormonal, and thymic development during critical periods to improve outcomes. Primary care providers were trained to screen universally for ACEs not merely to document history but to assess risk for a dysregulated physiologic stress response. Burke Harris noted, “For those who are at high risk of having a toxic stress response, we implement evidence-based interventions to regulate the stress physiology.”

One example of an evidence-based intervention is a University of California, Los Angeles, pilot study that examined the effectiveness of virtual mindfulness interventions in children screened for ACEs. Participants demonstrated measurable reductions in symptoms, as indicated by improvements in their Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores—a widely used depression screening tool. This study underscored the value of accessible nonclinical interventions that directly target physiological stress responses before they progress into more severe mental health conditions.

Additionally, Burke Harris discussed California’s policy shift, which expanded eligibility criteria for wraparound services based on the evidence

and the science of toxic stress. Previously, children required a formal diagnosis of a mental health disorder to receive support. However, under new guidelines, children with an ACE score of four or more could qualify based on their risk level alone. This approach enabled earlier detection through interventions such as the California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) program2 during critical developmental periods, potentially preventing long-term health consequences associated with toxic stress. The impact of this policy change was profound, dramatically increasing the number of children eligible for enhanced care management, substance use treatment, and mental health support. Burke Harris stressed that this model, currently implemented in California, could serve as a framework for other states or countries seeking to mitigate the intergenerational cycle of ACEs and stress-related health outcomes.

Building on these systemic efforts to address toxic stress, First 5 California3 launched a $120 million public education campaign that led to a 2.5-fold increase in community awareness of both toxic stress and ACEs, with 89 percent of respondents believing in the potential for children to heal from trauma and 88 percent confident in breaking the cycle of toxic stress. In parallel, a youth-designed campaign emerged, where messages crafted by young people for their peers resonated more effectively, highlighting the benefits of tailored, age-specific communication in supporting efforts to disrupt this cycle.

CLINICAL INTERVENTIONS AND PUBLIC HEALTH STRATEGIES PROMOTING RESILIENCE

Velma McBride Murry, university distinguished professor in the Department of Health Policy at the Vanderbilt School of Medicine and Department of Human and Organizational Development at Vanderbilt University, shared that the alarming 233 percent increase in suicide rates among Black youth over the last decade is a significant issue that highlights the need for greater public awareness and engagement from policymakers, researchers, and community leaders to identify and eliminate the root cause of lost lives among Black youth (Sheftall, 2023). This trend points to the need for thoughtful discussion and

___________________

2 CalAIM is an initiative to improve care and outcomes for millions of Medi-Cal enrollees. It is led by the California Department of Health Care Services. CalAIM builds on prior initiatives, like the Whole Person Care pilots, Health Homes program, Drug Medi-Cal Organized Delivery System, and the Coordinated Care Initiative. See https://calaim.dhcs.ca.gov/ (accessed July 18, 2025).

3 First 5 California is an initiative that aims to establish a comprehensive, integrated, and coordinated system to benefit California’s youngest children and their families, with a core mandate to enhance early childhood health, education, and family resilience (California First 5, 2025).

a deeper examination of contributing factors beyond the individual or family circumstances. McBride Murry highlighted that, although discussions of youth mental health disparities often take a broad approach, Black youth specifically experience an exceptionally high and disproportionate increase in suicide rates at younger ages (Sheftall, 2023). This troubling pattern, she underscored, requires interventions that address not only individual behaviors but also the broader structural and system level that has historically perpetuated a wide array of disparities.

McBride Murry introduced the concept of syndemic conditions, explaining that multiple interrelated stressors—including racial discrimination, neighborhood disadvantage, and economic instability—work together to compound health disparities, leading to early mortality and chronic disease (Lei et al., 2022). She pointed to evidence showing that 44 percent of ACEs are preventable, suggesting that reducing exposure to these conditions could significantly impact long-term health trajectories. Rather than viewing adversity in isolation, she framed syndemic conditions as systemic, reinforcing cycles of harm over generations.

Recognizing the continued need for systemic change, McBride Murry highlighted family-level interventions as part of the broader approach to mitigate adversities. McBride Murry pointed to the benefit of a racial-equityaffirming parenting program, a protective process targeted in the Pathways for African American Success (PAAS), designed to enhance parenting skills to foster resilience in their children. Racial-equity-affirming parenting is a socialization process by which parents equip their children with strategies to navigate adversity, particularly in the context of environments where they are at greater risk for experiencing racial stress and discrimination. PAASinduced racial-equity-affirming parenting demonstrated significant reductions in depressive symptoms among participating youth, even in the presence of racial discrimination.

This finding highlighted the protective role of culturally attuned parenting practices in buffering children from racialized adversities. McBride Murry also shared findings from a recent study, testing the extent to which PAAS enhanced brain functionality. This is the first study to merge prevention and neuroscience in a test of the effectiveness of a family-strength-based program to increase cognitive, emotional, and self-regulation behaviors among youth by enhancing both caregiver and youth protective processes. Findings revealed that youth assigned to the PAAS program demonstrated greater increases on neuronal coupling of the ventral striatum and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, brain regions associated with improved risk resistance coping skills, compared to youth assigned to waitlist control (Gillespie et al., 2020). Furthermore, results shed light on the importance of enhancing regions of the brain that influence optimal decision making, self-regulation, and emotional coping to

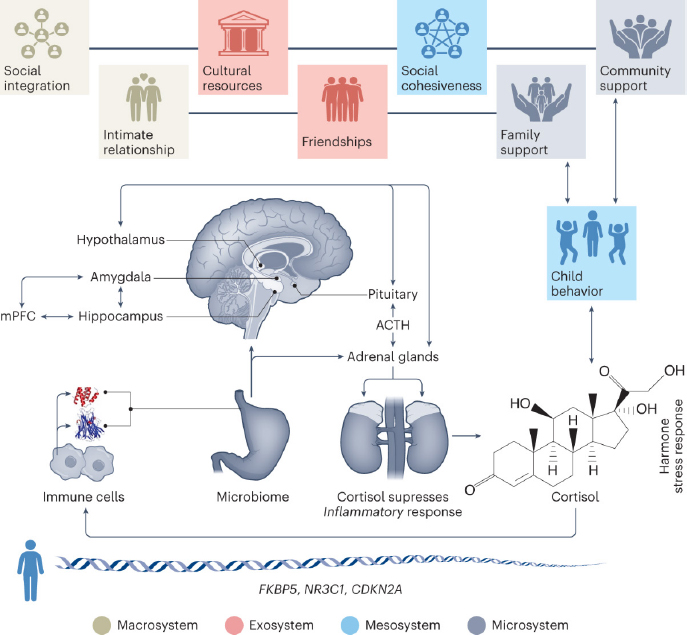

NOTE: ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; FKBP5 = FK506 binding protein 5; NR3C1 = nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1; CDKN2A = cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A; O = oxygen; H = hydrogen; OH = hydroxyl group.

SOURCES: Presented by Helen Minnis on March 25, 2025; adapted from Minnis et al., 2024.

prepare youth to navigate adversities, particularly challenges that elevate risk vulnerabilities.

In her final comments, McBride Murry added that merging findings from the brain functioning testing of PAAS to two of her other studies on the promotion of racial-equity-informed parenting and racial pride, noting that these studies collectively may offer insights on the importance of greater insight on how the protective nature of brain development in the midst of adversity. Being equipped with coping strategies through culturally attuned parental socialization may provide an environment to enhance awareness, and improve neural responses when processing environmental cues. These cues are

processed cognitively and emotionally, giving signals of how to respond in that manner that reduces hypervigilance and threat. This shift in attentional processing may contribute to reduced anxiety and stress-related disorders later in life. Altogether, McBride Murry’s findings underscored the need for systemic approaches integrating neuroscience and public health efforts to disrupt cycles of adversity and promote long-term well-being.

OPTIMISM IN TREATMENT AMONG COMPLEXITIES IN CHILDHOOD ABUSE

Helen Minnis, a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Glasgow, explored the need for better assessments of the complex interplay between childhood abuse and neglect and later mental health outcomes. Minnis began by noting that although abuse and neglect increase the risk of psychiatric issues, the global picture is not straightforward (Vila-Badia et al., 2021). For instance, epidemiological maps suggest that regions like sub-Saharan Africa, where exposure to abuse is reportedly high, do not necessarily show parallel rates of conditions such as schizophrenia, as seen in North America (Fernandes et al., 2021; Solmi et al., 2023). This contrast raises intriguing questions about the direct links between early adversity and later psychiatric disorders.

Delving into the science of early trauma, Minnis discussed research that emphasizes children’s biological capacity to adapt to adverse conditions. She referenced the Adaptive Calibration Model of Stress Responsivity—a framework that accounts for individual differences in stress responsivity as shaped by early environments and evolving across the lifespan—highlighting the idea that “children have evolved…to respond in biologically adaptive ways to harsh and unsupportive family environments, not just loving and supportive ones” (Del Giudice et al., 2011). These physiological adaptations can help children function in challenging contexts and may partly explain why some children exposed to severe abuse or neglect do not inevitably develop mental health problems. However, the model also recognizes that such adaptations occur within a broader context of risk, and adverse outcomes can still emerge, especially when environmental demands exceed the limits of these evolved coping mechanisms.

Expanding on this theme, Minnis introduced the concept of the “bioexposome” (see Figure 6-2). This framework captures the dynamic interactions among genetic predispositions, stress regulation, immune responses, the microbiome, neural development, and the broader social environment (Minnis et al., 2024). Using the example of a child reacting to traumatic experiences with elevated cortisol levels and observable externalizing behaviors, she illustrated how these early indicators could potentially steer life trajectories. In environments where supportive interventions or naturally nurturing

relationships emerge, the outlook may shift toward more positive social and developmental outcomes.

Another key point discussed was the complexity seen in neurodevelopmental profiles among children who have experienced abuse and neglect. Drawing on her clinical observations and a large twin study from Sweden, Minnis noted that children with early maltreatment were six times more likely to exhibit multiple neurodevelopmental conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, tic disorders, and learning disabilities (Minnis, 2013). Although Minnis initially thought that maltreatment was causing the heightened comorbidity among neurodevelopmental conditions, her findings pointed to additional genetic factors that might predispose the children to additional neurodevelopmental conditions. While the study could not explain what those genetic factors are, it raised the possibility that these factors may reflect neurodevelopmental conditions that run in families. If a child presents with such a condition, it is conceivable that the child’s parents might also experience heritable challenges in learning, impulse control, language, or social understanding. This perspective offers a measure of optimism, as the well-established support for neurodevelopmental conditions in both children and adults could hold promise in mitigating the impact of ACEs.

Minnis emphasized the importance of assessing abused and neglected children with respect for their journey, as earlier mentioned by Akil. She referenced a collaborative effort led by Rachel Hiller, in which international clinical academics examined how to approach such assessments. Their key finding was that despite the complexity of abused or neglected children’s experiences and needs, the underlying mental health symptoms requiring treatment are often straightforward (Hiller et al., 2023). Minnis noted that a holistic assessment can help identify these core issues, allowing for a clear and focused treatment approach.

Minnis underscored the urgent need to provide children who have experienced neglect or abuse with comprehensive assessments that form the foundation for high-quality, individualized care. Moreover, she reinforced the shared perspective among workshop presenters that resilience is not a static trait but a journey. She emphasized that both children and adults burdened by ACEs require steadfast compassionate support to empower them toward genuine thriving.

DISCUSSION

Economic Impacts in Early Intervention Strategies

Catherine Jensen Peña asked a question centered on the financial viability of early intervention programs that seek to prevent ACEs before they manifest

as full‐fledged clinical conditions. Burke Harris explained that since launching the initiative in 2020, her team has been examining data spread across various systems. The previous estimated lifetime impact of ACEs on direct health care cost was $124 billion, and the new estimate provided by the CDC rose to $14.1 trillion annually. Burke Harris pointed out that a significant portion of these expenses derives from costly conditions such as cardiovascular diseases and that even after accounting for traditional risk behaviors, biological factors—specifically, a dysregulated stress response combined with neuroendocrine and immune disruptions—continue to elevate risk for chronic conditions. This is in drastic contrast to the cost analysis of California’s coordinated public health approach, which estimated an annual cost of roughly $112.5 billion on California’s health care system. This contrast suggests that addressing only symptomatic diseases might result in interventions that are not only costly but only partially effective, compared to the cost-effective preventive approach.

Brian Dias inquired about the eligibility criteria for public health programs such as Medi-Cal, specifically whether children with four or more ACEs qualify independently of traditional eligibility requirements. Burke Harris explained that children at high risk for toxic stress are eligible for CalAIM under a clinical algorithm that assesses ACE scores, ACE-related health conditions, and family protective factors. She noted that a child with four or more ACEs who does not have a mental health diagnosis may not necessarily require care from a licensed mental health professional. To address the broader need for stress regulation, Burke Harris highlighted California’s efforts to train and expand the capacity of community-based organizations in evidence-based interventions—such as sleep, exercise, nutrition, mindfulness, mental health support, and healthy relationships. These initiatives are designed to be culturally and linguistically appropriate, helping to reduce the burden on the state’s mental health providers while increasing access to community-based care.

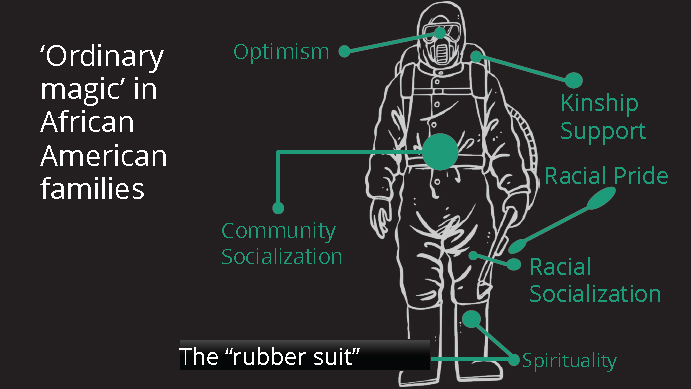

The “Rubber Suit” Metaphor: Cultural Resilience in Context

Simone Gentilhomme, a master’s student in social work at Howard University, introduced a metaphorical inquiry by asking about the notion of the “rubber suit” (Murry et al., 2023). McBride Murry came up with the concept of the “rubber suit” while looking at protective gear during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 6-3). It represents the socially inculcated coping mechanisms that Black families use to face toxic social and environmental challenges. In her depiction, optimism functions as the essential goggles—sharpening vision with hope and a forward-looking perspective—while the kinship system becomes a sturdy backpack, laden with the indispensable support of extended family and community. Racial pride acts as an antibacterial spray

SOURCES: Presented by Velma McBride Murry on March 25, 2025; adapted from Murry et al., 2023.

bottle, offsetting negative societal messages, and community socialization ties everything together like a reliable belt that holds the system in place. Finally, spirituality serves as the grounding boots, enabling individuals to advance steadily despite persistent systemic challenges. Together, these elements form a comprehensive, ever-adaptable defense—embodying both the resilience and the inevitable burdens of safeguarding oneself within systems marked by adversity. In response to Gentilhomme on her inquiry using McBride Murry’s metaphor of a “too-tight rubber suit” to describe clients overwhelmed by their own coping systems, Burke Harris emphasized that risk factors for developing the toxic stress response extend well beyond childhood maltreatment to include systemic factors like discrimination and poverty.

Dias questioned how the rubber suit metaphor accounts for “skin-deep resilience,” where outward displays of strength may mask underlying biological weathering, including inflammation. Minnis responded by underscoring the importance of family and community in fostering resilience, particularly in societies that have become increasingly nuclear. She reflected on the vital role of extended family networks—such as support from aunties, grandparents, and cousins as seen in Caribbean cultures—in buffering stress and promoting well-being. Minnis argued that in nuclear societies, individuals may experience a different kind of biological weathering, as they often face adversity alone rather than within a strong communal support system. She stressed that marginalized communities, which traditionally rely on extended family

structures, possess strengths that should be recognized and integrated into broader societal frameworks. Minnis advocated for surrounding children and young people with these extended support systems to help recalibrate their physiological responses to stress and enhance resilience.

McBride Murry expanded the conversation by considering resilience in the context of intergenerational survival and genetic inheritance. She pointed to historical examples, such as the survival of individuals during the transatlantic slave trade, suggesting that genetic and environmental factors have been transmitted across generations, contributing to intergenerational resilience. McBride Murry questioned how resilience traits might be “transported” from ancestors to the present, shaping how individuals navigate adversity today. She summarized findings from a longitudinal study of more than 800 families participating in the Family and Community Health Study, which has tracked both risk and protective processes in African American families since the early 1990s. Findings from McBride Murry and her colleagues have shown that despite generational poverty, families consistently exhibit protective mechanisms as pathways for their children to thrive. McBride Murry also raised concerns about the burdens placed on parents to “be resilient” so that their children will be healthy, arguing that greater attention should be given to supporting caregivers so that they are healthy and able to effectively nurture resilient children. Husseini Manji added to the conversation by highlighting the importance of caregiver support and the positive role of extended family structures in mental health outcomes, particularly in conditions like schizophrenia.

Understanding Trauma in a Complex Societal Context

Akil questioned whether the rising prevalence of mental health issues might be understood through a lens like the “hygiene hypothesis,” suggesting that just as exposure to microbes is integral to immune system functioning, a balanced engagement with life’s challenges might be necessary for building robust resilience. She wondered whether reduced exposure to adversity in some populations might contribute to rising depression rates. Minnis found the question intriguing but acknowledged the complexity of resilience. She pointed to historical contexts where shared experiences of hardship fostered social support, contrasting this with modern societies in which trauma can lead to increased fragility due to social isolation. While she recognized ongoing inequalities, she also suggested that some communities may have become overly insulated from adversity. Burke Harris challenged the idea that reduced exposure to adversity is a cause of rising depression rates. Instead, she framed trauma as an unavoidable part of life, much like microbial exposure. She emphasized that ACEs significantly increase the risk of numerous health conditions and argued that interventions often fail when they only address symp-

toms rather than the underlying dysregulated stress response. Christopher Weber, director of Global Science Initiatives at the Alzheimer’s Association, expanded on the discussion by drawing connections between structural inequities—such as interpersonal racism and neighborhood disadvantages—and later-life cognitive challenges.

Laura Bustamante praised the ACEs program, which provides children exposed to toxic stress with mental health support without conferring psychiatric diagnosis. She shared her personal experiences, reflecting on how despite being “a really resilient, really positive kid,” she believes she would have benefited from such a program. Burke Harris warned against overlooking the physiological consequences of trauma and advocated for a broader systemic approach to treatment. She underscored that while interventions at the individual level are valuable, transformative change also requires bolstering community relationships and cultivating societal infrastructure that nurtures healing.

Digital Mental Health Solutions

A workshop participant wondered about digital technology’s potential to scale supportive interventions, such as using AI and mental health chatbots. McBride Murry revisited her earlier research and described an electronic health version of a family-based preventive intervention program that was deployed across multiple digital platforms. She suggested that these methods may allow communities even in rural areas to access evidence-based approaches for regulating stress responses. In discussing digital literacy and the use of AI-driven mental health chatbots, McBride Murry noted that care must be taken to ensure these digital tools incorporate diverse cultural and linguistic perspectives. The conversation highlighted a vision of “virtual villages” where digital platforms serve as extensions of community-based care, helping to bridge gaps in access and support.

Bridging Research and Practice for Broader Societal Change

Throughout this chapter, workshop speakers highlighted the importance of identifying adverse experiences early to facilitate intervention and treatment. Negative factors such as racial discrimination, economic instability, and neighborhood disadvantage can cause severe physiological stress and aging. But strong, warm support systems have been repeatedly demonstrated to alleviate some of the biological burden of adverse experiences. Early interventions have also been demonstrated to not only improve health outcomes but also decrease the economic burden, which could be the target of public health and advocacy initiatives.

This page intentionally left blank.