Applying Neurobiological Insights on Stress to Foster Resilience Across Life Stages: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 3 Understanding the Neuroscience of Stress and Resilience

3

Understanding the Neuroscience of Stress and Resilience

Highlights

- In stress-susceptible mice, suppressing the activity of the lateral septum—a brain region that regulates social behavior—reduces avoidance behavior and improves social engagement, pointing to its role in shaping stress-related information. (Russo)

- Neural population, fear extinction, and genetic studies indicate that the amygdala may play a large role in stress susceptibility and resilience. (Cameron, Kheirbek, Ressler)

- Both preclinical and human studies have shown sex differences in stress susceptibility and resilience, emphasizing the need to consider biological sex when designing resilience-building interventions or treatments. (Baratta, Cameron)

- The long-term effects of trauma and resilience can span generations, suggesting that reducing stress in parents may foster greater emotional stability and adaptability in future generations. (Ressler)

- Resilience is dynamic and can be influenced by many factors, such as early life experiences (e.g., maternal separation), behavioral control, physical activity, antidepressants, support systems, sleep quality, and household stability. (Baratta, Cameron, Kheirbek, Ressler, Russo)

- Inconsistent definitions of resilience across research fields make translational comparisons challenging. (Hyde)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Michael Milham, senior child and adolescent psychiatrist, chief science officer, and founding director of the Center for the Developing Brain at the Child Mind Institute, described how the use of different preclinical (rodents, nonhuman primates) and clinical models has helped to uncover fundamental neural mechanisms of stress, examine how developmental and social factors shape responses, and ultimately provide insights into mental health across the lifespan. He emphasized that the findings from the speakers’ research offer crucial insights for designing interventions that better support individuals and communities facing adversity.

THE ROLE OF THE LATERAL SEPTUM IN SOCIAL TRAUMA

Scott Russo, professor of neuroscience and director of the Center for Affective Neuroscience and the Brain-Body Research Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, introduced a series of studies that use rodent models to probe the neural impact of negative social experiences. He noted that social behavior, maintained by evolutionary pressures, has played a critical role in enabling animals to detect predators, allocate limited resources, and enhance reproductive success. Russo added that these interactions offer positive affective experiences and serve as natural rewards. Yet when social experiences become traumatic, he explained, the very networks that provide support may transform into sources of distress. More specifically, Russo detailed how the brain encodes negative social experiences through activation of the lateral septum, a brain region associated with regulating social behaviors (Li et al., 2023). This activation reportedly suppresses downstream reward pathways, such as those projecting from the nucleus accumbens, a brain region important in processing reward, positive reinforcement, and pleasure (Li et al., 2023). This suppression of the reward pathways ultimately leads to

generalized social avoidance, and this effect is amplified by social trauma (Li et al., 2023). Therefore, Russo’s team employed a chemogenetic1 approach by using an inhibitory designer receptor exclusively activated by a designer drug (DREADD) to precisely silence lateral septum activity, which in turn reduced avoidance and boosted social interaction. Russo underscored two key brain-behavior features associated with traumatic social experiences: a blunted response to natural rewards (anhedonia) and an accentuated threat response during exposures to ambiguous stress signals (Li et al., 2023).

Russo also described a chronic social defeat stress model where genetically identical mice are subjected to brief five-minute bouts of social bullying from an aggressor mouse, repeated over a span of 10 days (Krishnan et al., 2007; Li et al., 2023; Navarrete et al., 2024). He demonstrated that, despite their uniform genetic background, experimental mice exhibit divergent responses: roughly half become stress susceptible while the other half show signs of resilience. Through modifications in standard paradigms (including resident intruder and social preference tests), his data suggested that stress not only triggers state-dependent neural activity but also leads to a generalized form of fear that impairs positive social interactions. Russo inferred that the lateral septum may be acting as a sensor that operates within the particular context of a stressful environment; the lateral septum registers environmental threat and also interacts dynamically with the brain’s reward systems to shape behavior. Rather than simply reflecting an absence of interest in social stimuli, these data suggest, the lateral septum may inhibit the brain’s capacity to experience social interactions as rewarding.

THE DYNAMICS OF THE AMYGDALA–HIPPOCAMPAL CIRCUIT IN STRESS RESILIENCE

Mazen Kheirbek, an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, and a member of the Kavli Institute for Fundamental Neuroscience, extended the discussion by explaining how real-time monitoring of neural population dynamics could help predict different stress responses in a rodent model of chronic stress. Kheirbek’s work harnesses Neuropixels2 to obtain simultaneous live recordings of large populations of neurons within the amygdala and hippocampus. Analysis of a

___________________

1 Chemogenetics is a method used in neuroscience that involves genetically engineering receptors to respond exclusively to synthetic chemical ligands. This allows researchers to precisely control cellular activity, particularly in neurons, by administering specific compounds that activate or inhibit these receptors without affecting natural signaling pathways (Menard and Russo, 2018).

2 Neuropixels is a silicon digital neural probe that allows for large-scale neural recording

six-minute time period revealed that the neural activity in stress-susceptible mice shifted through a greater number of distinct population states in the amygdala compared to that of control and stress-resilient populations (Xia et al., 2025). This variation in amygdala signaling emerges precisely during decision-making moments—such as when choosing between water and sucrose solutions—thereby potentially interfering with the normal valuation of rewards (Xia et al., 2025). Kheirbek explained that these inherent differences in the spontaneous resting activity of these regions can distinguish between control, stress-resilient, and stress-susceptible mice (Xia et al., 2025).

A particularly striking observation was the increased synchrony of activity between the ventral hippocampus and the amygdala in stress-resilient mice immediately before high-reward decisions, said Kheirbek (Xia et al., 2025). The data revealed that in stress-resilient mice, the ventral hippocampus and amygdala become more synchronized immediately before making high-value reward choices (Xia et al., 2025). Leveraging this observation, Kheirbek’s group used DREADD—the chemogenetic approach that employs designer receptors—to artificially enhance the correlation between these regions in stress-susceptible mice (Xia et al., 2025). By boosting this synchrony between the amygdala and hippocampus in stress-susceptible mice, Kheirbek’s group was able to rescue disrupted reward processing and reduce anhedonia-related behaviors.

STRESS CONTROLLABILITY AND SEX DIFFERENCES IN NEURAL RESPONSES

Michael Baratta, an assistant professor of behavioral neuroscience at the University of Colorado Boulder, pivoted the discussion toward how the ability to physically control a stressor—a coping behavior called stressor controllability—can buffer the impacts of stress and build resilience. Because resilience is deeply rooted in neural processing, Baratta’s research examines how stress-related experiences shape the rodent prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and limbic structures—key brain regions involved in decision making, emotional regulation, and adaptive behavior. His work focuses on how experiential factors like physical activity, stress coping, pharmacological resilience, and dominant status influence these neural circuits. He explained that human resilience is closely linked to coping strategies, which are categorized into emotion management and direct conflict resolution. While coping strategies are difficult to model in animals, behavioral control over stressors is a notable

___________________

with single-cell resolution. For more information, see https://www.neuropixels.org/ (accessed June 11, 2025).

exception and is commonly studied using an instrumental learning task. During the instrumental learning task, rats learn to turn a wheel to stop tail shocks (controllable stress), affecting both the rat itself and a yoked partner in the uncontrollable condition. For the uncontrollable stress subject, turning the wheel has no effect. Baratta explained that the physical stressor is the same between conditions, emphasizing that the experimental manipulation rests solely on the degree of control exercised over stopping the stressor. Baratta noted that decades of research have shown that when subjects are exposed to adverse events that they cannot control or escape, the stress can overwhelm certain brain pathways, leading to behavioral symptoms analogous to learned helplessness or depression (Maier and Watkins, 2005).

However, Baratta’s data revealed a crucial sex difference: Behavioral control was not protective in female rats (Baratta et al., 2018). Female rats in the controllable stress condition displayed similar symptoms of learned helplessness and depression as both male and female counterparts in the uncontrollable stress condition. Further investigations revealed that male rats primarily relied on a goal-directed pathway through the dorsomedial striatum, where actions were driven by outcome-based decision making. In contrast, female rats with behavioral control primarily relied on a habit-based pathway through the dorsolateral striatum driven by reflexive and automatic decision making. Moreover, in female rats, excess dopamine release in the prefrontal cortex appeared to suppress the goal-directed system, thereby limiting the protective benefits of behavioral control (Baratta et al., 2018). These findings suggest that the equivalent expression of behavioral control can be governed by two very different neural circuit mechanisms in males and females, with major implications for understanding stress resilience across sexes, said Baratta. He underscored the importance of examining resilience-specific mechanisms—not just the mechanisms of uncontrollable stress—thereby offering a nuanced view of how sex differences may shape health outcomes in response to stress.

EARLY LIFE STRESS AND THE ROLE OF SOCIAL SUPPORT

Bridging animal models to human developmental studies, Judy Cameron, professor of psychiatry, neuroscience, obstetrics, gynecology, and behavioral and community health sciences at the University of Pittsburgh, provided important context on the timing of stress exposure. Drawing from her nonhuman primate studies, Cameron contrasted outcomes in infant monkeys experiencing maternal separation at different developmental stages. For example, monkeys separated at one month of age exhibited a persistent increase in social avoidance, whereas those separated as one-week-olds, although initially distressed, later demonstrated some recovery when provided with timely social

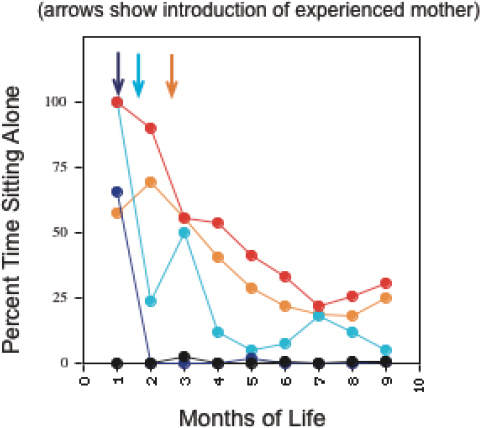

support through the comfort of a foster mother. She found that all 200 genes she examined in the amygdala were changed in three-month-old monkeys that experience just one week of early maternal separation. She highlighted that the gene that changed the most in the one-week- and one-month-separated animals was the soluble guanylate cyclase gene, identifying it as part of the nitric oxide pathway in the amygdala. Additionally, Cameron described a strong correlation between guanylate cyclase expression levels and social behavior, with lower expression associated with increased social avoidance. Cameron’s research also showed that even a few days’ delay in providing an adoptive mother’s support could result in markedly different long-term social behaviors (see Figure 3-1). She stressed that the timing of social support interventions in the immediate aftermath of early life stress is a critical factor for promoting resilience.

In parallel, her work with young children exposed to family stress underscored the mediating role of sleep in socioemotional and executive functioning.

NOTES: Percentage of time infant monkeys spend sitting alone following one-week maternal separation. Social recovery is compared across different intervention points: foster mother introduced at 25 days (purple), 35 days (blue), and 45 days (orange) postseparation. Additionally, behavioral outcomes are contrasted with infant monkeys who received no foster mother (red) and those who never experienced maternal separation (black).

SOURCE: Presented by Judy Cameron on March 24, 2025.

Her research indicates that children exposed to low resources, poor caregiver education, and chronic family stress exhibited impairments in social-emotional skills, attention, and problem solving. Importantly, Cameron identified sleep as a significant mediator of these effects. In her studies, children growing up in adverse environments who nonetheless got sufficient, quality sleep were more likely to maintain better developmental outcomes, despite the stressors. She noted that in statistical models, sleep appears to buffer the detriments of stress on children’s cognitive and social development. This finding points to sleep as a potential lever for resilience: Ensuring healthy sleep habits may help children cope with or recover from the effects of early adversity. During the discussion period, sleep was also raised as a protective factor to stressors.

Cameron also observed notable sex differences in how stress affects child development. For instance, in her data, exposure to high adversity was linked to increased attention problems in boys, whereas girls did not show the same degree of impact on attention (Cameron et al., 2017). This suggests that biological sex may influence vulnerability or resilience to certain stress-related outcomes, an important factor to consider when designing interventions, said Cameron. Factors like the timing of stress exposure, the availability of supportive relationships, and even basic health behaviors such as sleep may all shift a child’s trajectory toward susceptibility to stress and resilience. With better understanding of these developmental mechanisms, early life interventions may be tailored to foster resilience in vulnerable children.

RECOVERY, PLASTICITY, AND INTERGENERATIONAL MECHANISMS OF RESILIENCE

Kerry Ressler, chief scientific officer at McLean Hospital and professor at Harvard Medical School, focused on understanding resilience through the lens of trauma recovery and the neurobiological mechanisms underlying adaptation after stress. Drawing from the Grady Trauma Project, a large-scale study of civilian trauma in an urban, historically marginalized African American population, Ressler highlighted the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, noting that resilience moderates these effects (Wingo et al., 2010; Wrenn et al., 2010). He explained how genetic factors contribute to stress vulnerability. Ressler cited recent Psychiatric Genomics Consortium findings that identified 95 loci (genetic locations) linked to PTSD risk (Nievergelt et al., 2024). Moreover, they found that variations in the corticotropinreleasing hormone receptor—an important regulator of stress response, mood, metabolism, and other physiological functions—play a key role in individual differences in PTSD susceptibility (Nievergelt et al., 2024).

Ressler highlighted fear extinction, the process by which repeated passive exposure to fear-related stimuli, without reinforcement, gradually weakens

the fear response, as a model of resilience. His work began with an antibiotic drug (D-cycloserine) that enhances the brain’s ability to adapt and form new connections (or neural plasticity) by influencing specialized proteins important in learning and memory, called N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Ressler explained that their early studies showed that D-cycloserine could accelerate fear extinction in anxiety disorders, PTSD, obsessive compulsive disorder, and social anxiety. However, later findings revealed that when memories are reactivated, D-cycloserine could inadvertently strengthen fear memories rather than inhibit them (Ressler et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2002). Ressler suggested that some clinical trials may have faltered because not everyone was engaging in effective fear extinction learning. He raised the question of whether neural plasticity is always beneficial or if it must be carefully directed to avoid unintended effects. He proposed that future research should focus on pinpointing specific cellular mechanisms that promote fear inhibition—rather than risk reinforcing fear memories. One promising direction comes from Andreas Lüthi’s group, which identified “fear-off” neurons in the amygdala that activate specifically during extinction learning (Herry et al., 2008). Ressler emphasized the importance of understanding fear-off circuits in the amygdala to advance research on fear extinction and resilience.

He then connected this to intergenerational effects of trauma that demonstrated that children of mothers exposed to high levels of abuse face an increased physiological risk for stress-related responses (Jovanovic et al., 2011; Stenson et al., 2021). Ressler emphasized that this includes heightened startle reactions and increased sympathetic nervous system activation.

Building on this understanding of fear responses, Ressler discussed research on sensory modulation in the olfactory system. His lab found that mice conditioned to fear an odor developed enhanced neuronal and structural changes in the olfactory bulb, such as increased glomerular size (Jones et al., 2007). They also demonstrated that these changes were passed down to the next generation—even without direct exposure to the fearful odor (Dias and Ressler, 2014). Further research revealed that fear extinction reversed these structural changes, raising the question of whether resilience can be inherited (Morrison et al., 2015). Ressler referenced a study that found that when fathers underwent extinction training before mating, their offspring no longer exhibited fear-related structural changes (Aoued et al., 2019). Ressler suggested that treating the parental generation could break the cycle of fear transmission through behavioral and epigenetic mechanisms.

DISCUSSION

Translating from Animal Models to Human Interventions

Aleksandra Vicentic, a branch chief at the National Institute of Mental Health, opened by pointing out that while animal models offer clear insights into controlled factors like stress timing and context, translating these findings to the human experience is challenging. Milham challenged the panel to elaborate about how resilience and stress are defined across species, how findings can be translated between species, and the role of timing in these processes. Ressler explained that while basic science researchers often bear the responsibility for translating findings, psychiatry still struggles with achieving measurable, reproducible biomarkers and behavioral tests. He pointed out that psychiatric diagnoses have remained largely unchanged for a century, relying on self-reported feelings rather than objective markers. However, the shift toward biomarkers, quantitative behavioral approaches, and brain-based measures will improve reproducibility and facilitate translation across mammalian species. Cameron underscored the importance of treatment timing by noting that animal studies reveal limited time windows during which neural circuits remain malleable, suggesting that identifying similar windows in humans could improve treatment efficacy. “It isn’t that one type of intervention at one time is always going to work,” she added. Cameron noted that different stresses alter distinct circuits and advocated for precision in targeting interventions: “The science is telling us that we need to target our interventions to specific times and to specific stresses.” Cameron also pointed out that while science supports early intervention, societal challenges make it difficult to reach children experiencing stress early.

Baratta emphasized the need for a framework that organizes behavioral and cognitive dimensions that contribute to resilience. He noted that different resilience factors—such as exercise, safety signals, and enhanced extinction learning—may operate through distinct pathways and mechanisms rather than affecting all aspects of resilience uniformly. Baratta also suggested that there must be a neural system that integrates these dimensions, allowing for behavioral flexibility and adaptation. He pointed out that freezing behaviors, for example, would limit one’s ability to explore new contingencies, implying that resilience mechanisms need to be compatible with broader adaptive behaviors. Baratta also questioned whether there is a specific brain structure responsible for coordinating these interconnected resilience-promoting factors.

Adding a technological perspective, Kheirbek highlighted that advances like high-resolution functional magnetic resonance imaging and other direct neural recording techniques have emerged only in the past 10 to 20 years. These innovations in human research enable a reverse translation process,

where observations in human studies guide further exploration in animal models. He concluded that this approach fosters a bidirectional integration between basic science and clinical research. Cameron supported the idea that moving between human and animal models can deepen understanding. She described how a chance meeting with Takao Hensch, a researcher from Boston Children’s Hospital, led to a pivotal discovery—attention mechanisms observed in children mirrored findings from his studies in mice. This prompted Hensch to revisit his animal research, reconfirming this result. Cameron added that the mouse model provided a valuable opportunity to investigate neural mechanisms in greater detail, such as dopamine receptor changes in the anterior cingulate—insights that would have been impossible to examine directly in humans (Makino et al., 2024).

Brian Dias, an associate professor at the University of Southern California, asked how long-lasting the chemogenetic stimulation effects were and whether boosts were needed. Kheirbek stated that his team had not yet tested the long-term effects of chemogenetic stimulation, but they were actively investigating whether plasticity within the circuit could be induced to create lasting change. He referenced deep brain stimulation research, noting that repeated stimulation can enhance plasticity over time, leading to greater circuit excitability.

Luke Williamson Hyde, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, raised concerns about inconsistent definitions of resilience across research fields, making translational comparisons challenging. He explained that the National Institutes of Health convened researchers who had received funding via a specific grant-funding mechanism focused on resilience with projects ranging from child development to military veterans and PTSD. One goal of the meeting was to establish standardized definitions of resilience or standardized measures. However, after two days of discussion, they were unable to reach a consensus because resilience is highly context dependent. Hyde explained that different fields study resilience in distinct ways, making it difficult to apply a single definition across disciplines, but also that substantial work on resilience and its definitions in human developmental science has often not penetrated to researchers in other fields.

Demographic Factors Contributing to Resilience

A workshop participant asked Cameron whether her research, which identified sex differences, also examined ethnic, cultural, or racial differences in resilience and development. Additionally, the audience sought insight into trauma- and thriving-informed approaches to better distinguish resilience from depression, especially in diverse and vulnerable populations. Cameron explained that her studies, which included children from Canada and the

United States, have not found ethnic or racial differences despite examining diverse samples. She noted that this does not mean such differences do not exist, only that her team has not observed them. However, they did find sex differences, particularly in attention-related outcomes among males. She cautioned against assuming sex-based findings are absolute, suggesting that high levels of stress might impact girls in similar ways under certain conditions. Ressler added that in national cohort studies where racial or cultural differences have been observed in trauma or depression outcomes, those differences have almost always been moderated or mitigated by socioeconomic factors such as poverty, adversity, and access to green space. Kheirbek also acknowledged challenges in studying resilience at the population level, noting that resilient individuals are less likely to enroll in clinical trials because they are otherwise psychologically healthy. Ressler suggested the the ABCD (Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development) study as a valuable resource for examining resilience across healthy and at-risk populations, ensuring a broad symptom spectrum beyond strictly clinical samples.3

In a related line of inquiry, Herman Taylor, a cardiologist and director at the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Morehouse College of Medicine, asked whether experimental models account for acute-on-chronic adversity, where populations experience long-term generational hardship alongside new acute stressors, such as policy changes, violence, or environmental instability. He inquired whether any models exist to examine the vulnerability, susceptibility, and resilience associated with this compounded adversity. Ressler confirmed that models addressing acute-on-chronic adversity do exist, though the topic is complex and requires multifaceted approaches. He explained that in human studies, patterns of poverty and adversity tend to increase risk, particularly when a new trauma is added to childhood trauma, exacerbating susceptibility. Ressler added that in mouse models, researchers see similar effects: For example, mice exposed to chronic social defeat in adolescence display heightened fear responses and reduced ability to extinguish fear conditioning when tested in adulthood. He emphasized that the neural mechanisms underlying this process are complex, but there is clear evidence of an additive effect, where prior adversity amplifies the impact of later stressors.

The Dynamic Nature of Resilience

Vicentic posed a question on whether resilience is better understood as an innate trait or a flexible state that may be measured before or after trauma

___________________

3 The ABCD study is a longitudinal study following the biological and behavioral development of children through adolescence and into adulthood. For more information, see https://abcdstudy.org/ (accessed June 11, 2025).

exposure. Building on that, she wondered if resilience exists as a trait prior to experiencing adversity or if it is instead a more positive coping strategy after adversity happens. In response, Ressler clarified that resilience is not merely the absence of vulnerability but rather the ability to bounce back or recover from adversity. He noted that neural circuit mechanisms may influence susceptibility or resilience differently as well. Ressler also brought forth the concept of “traumatic growth”—the idea that exposure to manageable levels of stress could, under the right conditions, catalyze personal development and better coping mechanisms. Beyond self-report measures, emerging techniques in the integration of machine learning with neuroimaging and behavioral studies may offer innovative ways to quantify these phenomena, although the conversation acknowledged that much work remains to capture the full continuum of resilience in diverse populations. Kheirbek pointed to animal model research, explaining that resilient mice exhibit unique neural activity compared to both unstressed controls and susceptible mice. He cited findings from Eric Nestler’s lab, showing that dopamine neuron activity in the ventral tegmental area adapts uniquely in resilient mice and can be manipulated to promote behavioral resilience.

Indida Birto asked whether there is a predictable threshold for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—a “make-it-or-break-it” number—beyond which resilience becomes harder to maintain. She acknowledged that recovery is always possible but wondered whether a specific number of ACEs allows researchers to predict long-term outcomes. Cameron emphasized that adversity is often repeated throughout life, and early exposure increases the likelihood of experiencing additional adversity later. She pointed out that brain circuits develop until age 25, meaning that the timing, type, and affected neural circuits play a role in how adversity influences outcomes. Cameron concluded that there is no universal threshold, as each experience interacts uniquely with development. Ressler reinforced this by noting that PTSD rarely develops from a single trauma—instead, risk tends to increase with repeated interpersonal adversity. He added that much of childhood trauma is relational, such as ongoing abuse, which compounds over time. Ressler also highlighted a gap in self-reported trauma data, explaining that declarative memories form around ages three to four, while emotional memories begin at birth. This raised concerns that early adversity may impact individuals in ways that they cannot consciously recall, leading to underreported trauma histories in studies.

Factors That Can Foster Resilience

Another topic that generated considerable interest was whether positive enrichment following a stressor might push neural circuits toward a more resilient state. Frances Jensen, a professor of neurology and the chair of the

neurology department at the Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania, asked whether resilience could be actively fostered through enrichment rather than simply removing stressors. She wondered if introducing positive rewards at key moments—particularly in susceptible animals—could counteract stress-induced network dysfunction and promote lasting resilience. Cameron agreed that enrichment can be effective when applied while neural circuits remain plastic. She pointed out that stress affects multiple circuits over time, raising the question of whether targeted enrichment could influence different circuits at different developmental stages. Kheirbek highlighted research showing that enrichment can boost adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus, citing work by Chris Anacker and Rene Hen demonstrating its role in promoting resilience. Russo emphasized that environmental enrichment, physical activity, antidepressants, and social buffering all contribute to resilience in animal models. Baratta added that behavioral control during late adolescence in rats leads to longer-lasting protective effects compared to adulthood, suggesting critical windows where interventions may be more effective.

Alexa Ryan, a senior at Howard University at the time, asked whether certain stressors can increase resilience rather than decrease it. Ressler noted that there is a body of literature on traumatic growth, but much remains unclear. He suggested that controllability plays a key role, explaining that individuals who face stressors but have strong support systems—such as parents, mentors, or coaches—may develop a resilient, perseverant personality rather than experiencing learned helplessness. However, he acknowledged that more studies are needed to fully understand this process. Baratta reinforced that resilience emerges within adversity, explaining that resilience-related neural circuits require activation under stressful conditions to be protective. He emphasized that certain early life stressors can produce long-lasting resilience, but only if tied to adversity itself rather than occurring in a neutral setting. Ressler added a follow-up, referencing Tallie Baram’s research on predictability despite negative experiences. He shared a powerful finding from his team’s work at the Grady Trauma Project, where asking participants whether they grew up in a stable or unstable household proved to be a highly predictive factor for resilience outcomes, suggesting that stability—regardless of adversity—plays a crucial role in fostering resilience.

The Negative Effects of Sustained Resilience

Laura Bustamante, a postdoctoral researcher at Washington University in St. Louis, referenced the John Henryism hypothesis, which suggests that effortful active coping can be beneficial for those in advantaged positions (e.g., higher education) but can lead to negative health outcomes, such as cardiovascular issues, for individuals in disadvantaged circumstances. Bustamante wondered whether animal models could be used to explore these neurobiologi-

cal interactions between resilient and vulnerable subjects. Russo agreed that resilience research raises important concerns, including for type-A individuals (individuals who tend to be perceived as highly motivated, goal-oriented, and independent) who exhibit high psychological resilience but increased cardiovascular risk. He explained that in their psychosocial stress models, mice that are susceptible to stress tend to show broad vulnerability across multiple domains, whereas resilient mice experience benefits beyond psychological adaptation, including lower cardiovascular disease risk and improved response to statins. However, he cautioned that this does not apply to all definitions of resilience. Baratta described his team’s coping-with-stress paradigm, in which animals can turn a wheel to mitigate stress exposure, leading to long-term behavioral protection. However, he noted that while behavioral resilience improves, immune system activity, autonomic nervous system function, and endocrine responses remain elevated, suggesting that even resilient individuals may still experience physiological strain.

Digital Technologies and Biological Measurements

Milham asked about advancing behavioral measurement, particularly in relation to digital technologies. He sought insights into whether these tools could improve cross-species research and help integrate findings across the lifespan. Russo highlighted several digital tools that are expanding behavioral measurement capabilities, including smartphones, wearable devices, and natural language processing. He pointed out that smartphones can provide both active and passive data, such as texting patterns and behavioral insights, while wearable devices can measure physiological factors like heart rate, temperature, and sleep patterns. Russo emphasized that quantitative sleep tracking has improved significantly, allowing researchers to study sleep behaviors across mammals and apply findings to younger populations. He suggested that these technologies could play a crucial role in bridging behavioral research across species and the lifespan, offering new opportunities for data collection and analysis.

Eva Feldman, a neurologist at the University of Michigan, asked whether researchers are using the All of Us cohort4 for their work and whether doing so would be valuable. She also inquired about the use of AI to integrate human data with preclinical findings. Cameron stated that her team is not using the All of Us cohort but is actively employing machine learning to analyze videotaped behavior in children and monkeys. She explained that

___________________

4 All of Us is a National Institutes of Health program created to build a diverse database that can inform thousands of studies on a variety of health conditions. See https://allofus.nih.gov/article/program-overview (accessed June 11, 2025).

researchers are trained to observe specific behaviors, and AI could help identify overlooked behavioral patterns in developmental studies. Cameron noted that machine learning has already yielded valuable insights in rodent research. Ressler described All of Us as an exciting and large-scale initiative, though its data availability is still rolling out. He compared it to the ABCD cohort, which has been instrumental in developmental research, and predicted that All of Us will soon have a similar impact. Ressler also discussed AI applications, noting that researchers have used machine-learning tools like DeepLabCut for videobased behavioral analysis. While AI has been useful for genetic comparisons between animal models and humans, he acknowledged that researchers have yet to fully bridge the gap at the behavioral circuit level.

Sleep and Stress Management: Public Health and Cultural Perspectives

Diane Bovenkamp, vice president of scientific affairs at BrightFocus® Foundation, asked about leveraging population health approaches to improve sleep and stress management, particularly in public schools or health care settings. She suggested offering digital tools, such as apps like Calm, to support better sleep habits, noting that stressors like social media are often unpredictable. She also wondered whether a billing code for sleep interventions could encourage doctors and pediatricians to integrate preventive measures into routine care. Cameron emphasized that sleep plays a critical role in childhood development, serving as a mediator for cognitive, emotional, and problemsolving abilities. She noted that her team has studied sleep insufficiency and poor sleep quality, finding that 79 percent of children in their research do not get enough sleep. She acknowledged the potential for broad interventions but expressed caution about mass-scale programs without careful tailoring. Ressler expanded on intervention strategies, highlighting that short-term treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy are effective in improving emotion regulation and cognitive flexibility. He suggested that integrating these interventions into school health programs or prenatal care could have wide-reaching benefits for resilience and mental health.

A workshop participant asked how sleep physiology, alongside factors such as emotional regulation, neuroendocrine function, and developmental timing, influences neural circuit vulnerability or protection against substance misuse, personal violence, and social defeat. The participant also inquired about whether sleep deprivation acts as a confounder, distorting study results by making it appear as though one factor causes another when, in reality, an unaccounted-for third variable is driving the relationship. Cynthia Rogers, the Blanche F. Ittleson Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics and vice chair and division director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Washington

University in St. Louis, shared that her team, including Caroline Hoyniak, is studying maternal and child sleep through polysomnography and at-home sleep studies. She highlighted research showing that maternal sleep affects brain development, suggesting that child sleep is likely to play a significant role as well. While she acknowledged the clinical importance of sleep for development and mental health, she noted that her team has not yet examined sleep at the molecular or biological level. Catherine Jensen Peña, an assistant professor at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, emphasized that disrupted sleep is a strong cross-species factor, making it a critical target for research in understanding neurodevelopmental effects. Nadine Burke Harris, senior advisor for the ACE Resource Network and former surgeon general of California, pointed out that sleep regulation affects the sympathoadrenal medullary and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axes, which play key roles in stress and neuroendocrine function.

Dias asked Cameron about sleep education programs, specifically how cultural perspectives, such as co-sleeping, influence approaches to sleep education. He shared a personal experience of being shamed in parental groups for allowing co-sleeping, despite its prevalence globally. Cameron responded that her research on sleep education programs focuses primarily on families in impoverished conditions, where co-sleeping and frequent relocation are common. She explained that her team adapts sleep strategies to fit these realities, such as recommending that children sleep on portable mattresses in consistent locations to maintain a sense of stability. Cameron also described her approach to tailoring sleep routines, emphasizing practical strategies like having children wear the same T-shirt to sleep instead of conventional pajamas, which may be unrealistic for families in poverty. She underscored the challenges of external disruptions, such as violence and loud noises, and highlighted efforts to help parents manage these stressors to support their child’s sleep.

In sum, preclinical research has focused on identifying the brain regions that underlie stress susceptibility and resilience, including the lateral septum, amygdala, dorsolateral striatum, and dorsomedial striatum. This can create opportunities for new targeted biomarkers, diagnostics, and treatments to cultivate resilience. However, there remains more to learn about the individual variability and dynamic nature of resilience, such as the contribution of factors such as sex, race, or cultural difference.