Applying Neurobiological Insights on Stress to Foster Resilience Across Life Stages: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 4 Critical and Sensitive Periods to Build Resilience

4

Critical and Sensitive Periods to Build Resilience

Highlights

- The timing of stress exposure determines which neural circuits are affected. Understanding these temporal dynamics allows researchers to design targeted interventions that align with specific developmental stages to optimize resilience-building. (Hyde, Meaney, Peña)

- An individual’s environment shapes biological susceptibility to both stress and resilience. Understanding the mechanisms underlying responses to negative environmental factors—evident in both rodent and human studies—can be leveraged to develop interventions that buffer the long-term effects of severe stress and foster resilience. (Dias, Meaney, Peña, Rogers)

- Early life adversity alters key epigenetic markers, shaping neural circuits that regulate emotional and cognitive responses, that can persist into adulthood and amplify susceptibility to mental health disorders but also enhance responsiveness to environmental or neurobiological interventions. (Meaney, Peña)

- Parenthood induces neuroplastic changes that enhance caregiving and resilience but also increase vulnerability to mood disorders, reinforcing the need for targeted interventions during this life stage. (Saxbe)

- Many resilience factors do not operate as expected in contexts of extreme disadvantage, highlighting the need to address systemic barriers—like housing stability, food security, and access to education—alongside individual or parenting interventions. (Rogers)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Brian Dias highlighted that critical periods are not solely times when stress profoundly impacts biological systems but also moments when resilience may be actively built. Dias emphasized that while infancy and adolescence are traditionally recognized as epochs where stress “gets under the skin,” these periods also represent windows in which environmental inputs can promote adaptive responses (Taylor et al., 2025). The research presented in this chapter highlights how windows of heightened susceptibility to stress can also serve as periods when resilience may be built. As several workshop speakers described, the developmental trajectories—in utero, early childhood, adolescence, or the transition to parenthood—reflect an intricate dialogue between environmental challenges and biological adaptations (Ho and King, 2021).

ANIMAL MODELS OF EARLY LIFE STRESS AND EPIGENETIC PRIMING

Catherine Jensen Peña described work in rodent models that examines the interplay between early life stress and later vulnerability to the development of stress-related disorders. Peña’s research utilizes paradigms of early stress across the lifespan (Peña, 2025; Peña et al., 2017, 2019). She noted that the timing of stress exposure in animal models should be selected with consideration of how it maps onto key periods of human brain development. In her own research, Peña’s lab uses early life stress from postnatal days 10 to 17 in rodents, which she noted roughly corresponds to early childhood in humans for certain brain regions (Peña, 2025). These paradigms include a combination of early life stress such as maternal separation and resource restriction in rodents to mimic aspects of childhood adversity and adult stress, such as the chronic social defeat

model shared earlier by Scott Russo. These manipulations, when combined, not only elevate risks for mood and anxiety disorders in animals but also create measurable changes in brain development long before stress symptoms emerge. Peña found that early life stress changes the expression of a number of genes across different brain regions related to nervous system development that last into adulthood. Furthermore, individuals with early life stress experiences that are exposed to stress as adults have epigenome-modulated changes in gene expression—that is, those life experiences influence gene activity without altering the underlying DNA sequence.

A key focus of Peña’s investigation is epigenome priming. Epigenome priming refers to the process by which early life experiences—such as stress or environmental factors—modify chromatin structure, making specific regions of the genome more accessible for future transcriptional activation (Peña, 2025; Peña et al., 2017). This means that certain genes become “prepped” to respond more strongly to later stressors, shaping susceptibility to stress or resilience across development. She explained that early life stress is associated with persistent chromatin modifications—most notably monomethylation of histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me1)—in brain areas important for reward and stress regulation, such as the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens (Geiger et al., 2025). These epigenetic marks reduce the stress response threshold, triggering transcriptional change and therefore making the brain more sensitive to stress over time. Peña further discussed experiments where increased levels of the enzyme responsible for establishing these modifications, when experimentally overexpressed, led to elevated stress responsiveness at transcriptional, physiological, and behavioral levels (Peña, 2025; Peña et al., 2017, 2019). Moreover, her group explored thyroid hormone modulation as an upstream factor that may influence this epigenetic priming process, noting that early life stress could suppress active thyroid hormone levels, with brief synthetic thyroid hormone treatments in rodents later promoting resilience in the face of additional stress (Bennett et al., 2024).

ENVIRONMENTAL ENRICHMENT AS A PATHWAY TO RESILIENCE ACTIVATION

Michael Meaney, professor and James McGill Chair Emeritus in Medicine at McGill University, highlighted how both biological predispositions and environmental interventions can work together to promote resilience in individuals facing adversity. Meaney used a conceptual model for understanding the origins of psychopathology of stress and resilience called the stress diathesis framework. This framework suggests that under mild or positive environmental conditions, variations in mental health and well-being remain relatively small. However, as adversity increases, individual differences emerge—some

people remain resilient, while others become more vulnerable to mental health challenges.

Meaney tested the stress diathesis framework using a rodent population exposed to environmental enrichment as a resilience model. He described how under conditions of sustained environmental enrichment during post-weaning to early adulthood, rodents display reduced stress reactivity and improved recovery after stressful events. Meaney’s team has shown that enrichment not only increases neurogenesis in both dorsal and ventral regions of the hippocampus but also appears to boost executive functions like attention and cognitive flexibility (Pataskar et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018). This suggests that enrichment strengthens the brain’s ability to adapt to stress.

A noteworthy aspect of Meaney’s research was the translation of these findings to human populations. His team mapped the human orthologs—biological counterparts—of the genes upregulated in enriched mice and identified expression-based single nucleotide polymorphisms, which are DNA variations that functionally regulate gene expression. By compiling these variations into a targeted genetic profile, Meaney’s team created a polygenic score for enrichment, reflecting the genetic capacity for the expression of enrichmentassociated genes in humans. This score was then tested using data from more than 500,000 individuals through the UK Biobank,1 providing insights into how individual genetic predispositions might shape resilience to stress and adversity. His team found that among individuals experiencing high levels of stress, those with higher enrichment polygenic scores exhibited fewer symptoms of depression and a lower probability of mood disorders. Importantly, this genetic influence was only observed in those exposed to substantial adversity—for individuals with low or modest stress levels, the polygenic score had no effect on depression symptoms. This suggests that enrichment-related gene expression functions as a buffer specifically when faced with significant life challenges.

Meaney discussed environmental enrichment as one potential approach to promoting resilience, showing that structured interventions—like classroombased executive function training—may help enhance cognitive flexibility and emotional regulation, particularly in high-risk populations. He emphasized that resilience-building strategies should target both individual traits and broader structural factors, ensuring that families and communities have the stability needed to support positive developmental outcomes.

___________________

1 For more information on the UK Biobank, see https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/ (accessed June 2, 2025).

PRENATAL AND EARLY CHILDHOOD ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES ON BRAIN STRUCTURE

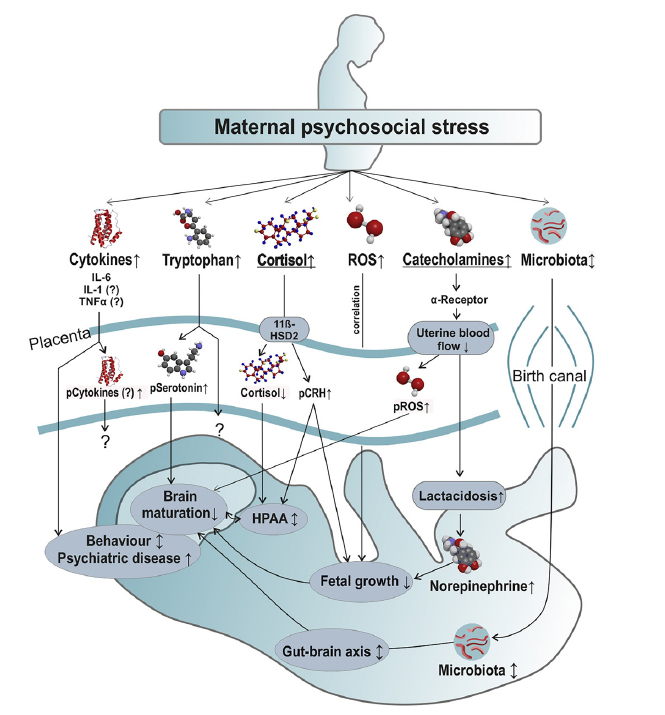

Cynthia Rogers focused on how social determinants of health impact infant brain development and early childhood social and emotional growth (Rakers et al., 2017). Her study, eLABE (Early Life Adversity, Biological Embedding, and Risk for Developmental Precursors of Mental Disorders), followed nearly 400 pregnant individuals through the third trimester and assessed how prenatal stress, inflammation, and environmental factors shaped neonatal brain structure (see Figure 4-1).

Rogers’s findings showed that higher social disadvantage correlated with reduced neonatal brain volumes across multiple tissue types, affecting limbic structures like the amygdala and hippocampus. Structural connectivity in key white matter tracts that connect brain regions involved in emotion regulation, memory, and cognitive processing—such as the cingulum, fornix, and uncinate—was disrupted in infants exposed to greater prenatal social adversity. She identified maternal IL-6 levels (interleukin 6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine) as biological mediators, linking social disadvantage to altered neonatal brain volume (Sanders et al., 2024). Additionally, maternal sleep disturbances during pregnancy were associated with reductions in cortical volume and surface area at birth.

Rogers’s research also explored environmental stressors like violent crime exposure (Brady et al., 2022). She found that even after adjusting for socioeconomic status and other environmental stressors, prenatal exposure to violent crime still had measurable effects on neonatal brain connectivity—particularly in regions like the amygdala and hippocampus. According to Rogers, this suggests that violent crime itself is a distinct factor influencing early brain development, beyond the broader effects of poverty or social disadvantage.

Turning to mechanisms that support resilience, Rogers’s research found that supportive parenting plays a crucial role in early childhood development, particularly in cognitive and language growth (Leverett et al., 2025). While supportive parenting behaviors such as sensitivity and positive regard were associated with higher cognitive and language scores in children with moderate social disadvantage, they did not significantly improve outcomes for children with severe social disadvantage (Leverett et al., 2025). Therefore, Rogers observed that while supportive parenting can help buffer stress and promote development, it may not be enough on its own to offset the impact of extreme socioeconomic hardship.

Rogers also examined the Thrive Factor, a set of postnatal resilience supports—including nutrition, neighborhood safety, child sleep, positive caregiving, and environmental stimulation—to determine whether it could mitigate the effects of early social disadvantage on socioemotional function-

NOTES: Six potential mediators of maternal–fetal stress: cytokines, serotonin/tryptophan, cortisol, reactive oxygen species (ROS), catecholamines, and maternal microbiota. IL-6 = interleukin 6; IL-1 = interleukin 1; TNFα = tumor necrosis factor-alpha; p = phosphorylated; pCRH = phosphorylated corticotropin-releasing hormone; pROS = phosphorylated reactive oxygen species; HPAA = hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis; α-receptor = alpha-adrenergic receptor; 11β-HSD2 = 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2.

SOURCES: Presented by Cynthia Rogers on March 25, 2025; adapted from Rakers et al., 2017, and reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

ing, cognitive, and structural brain outcomes (Luby et al., 2024). Her findings revealed a complex relationship between these protective factors and socioeconomic status. Higher Thrive Factor scores were also associated with lower internalizing scores for children facing high levels of social disadvantage. While children from less disadvantaged backgrounds showed stronger cognitive and language benefits when exposed to high levels of Thrive Factor supports, children with more extreme social disadvantage did not experience the protective effects. She noted that for families facing greater social disadvantage, these protective influences were less effective at offsetting developmental disparities. Rogers emphasized that broader structural interventions, such as housing stability, access to health care, and community support, may be necessary to fully unlock the benefits of resilience support for children in highly disadvantaged environments. As her study enters its next phase, Rogers aims to further investigate child-level and community-based resilience mechanisms, including school and neighborhood supports that may shape long-term developmental outcomes.

EARLY CHILDHOOD ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES ON ADOLESCENT BRAIN

Luke Williamson Hyde described how early adversity and neighborhood disadvantage affect brain development and behavior in children. He emphasized the significant role environmental influences play in shaping long-term outcomes. Hyde’s work integrates longitudinal studies, neuroimaging, and behavior genetics to understand risk and resilience in youth growing up in high-stress environments.

Complementing Rogers’s work, Hyde examined the effects of neighborhood violence on neural development in adolescents. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), his team found that youth exposed to higher community violence in early childhood exhibited increased amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli, suggesting heightened sensitivity to threat (Gard et al., 2017, 2022a) and lower activity in the inferior frontal gyrus during inhibition and lower inhibitory control (Westerman et al., 2024) and greater activity in the ventral striatum, potentially increasing vulnerability to later mental health challenges. His work also highlighted how parenting serves as a stress buffer—youth with more nurturing caregivers showed less pronounced neural alterations, suggesting a buffering effect against adversity.

Consistent with earlier workshop discussions, the findings underscore that the effects of adverse exposures hinge on their timing. Early exposures, such as harsh parenting at age three or neighborhood disadvantage in early childhood, were linked to heightened amygdala activity—a subcortical region that develops early, which plays a key role in threat detection, emotional

processing, and other functions (Gard et al., 2022b). And exposures later in development, including changes in parenting over childhood or neighborhood disadvantage during adolescence, relate to altered activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, a later-developing prefrontal area critical for emotion regulation (Hyde et al., 2022).

Broader adversities are inevitably funneled through immediate family experiences—a concept that is illustrated in Rand Conger’s family stress model (Conger et al., 1992). In this model, poverty and economic pressure elevate parental stress, which then manifests as harsher parenting practices, ultimately linking to child mental health challenges. Hyde’s brain data align with this view, reinforcing the idea that the impact of widespread adversity is mediated by more intimate, proximal interpersonal experiences that directly affect developmental outcomes.

In exploring the link between low-income neighborhoods and brain development, research has identified community violence as a key mechanism, with increased exposure predicting heightened amygdala responses to threat and altered ventral striatum activity to reward (Suarez et al., 2024; Westerman et al., 2024). However, positive social buffers emerge across multiple studies: Warm, involved parents both reduce the likelihood of exposure to such violence and temper its neurotoxic impact, while neighbors with strong protective norms further shield youth from these adverse effects (Gard et al., 2022a; Suarez et al., 2022). His findings emphasize the need for communitylevel interventions, advocating for policies that support families and reduce structural inequalities to encourage healthier brain development in children.

TRANSITION TO PARENTHOOD: A UNIQUE WINDOW FOR NEUROPLASTICITY

Darby Saxbe, a professor of psychology at the University of Southern California, examined the transition to parenthood as another critical window during which profound neuroplastic changes occur. Saxbe’s research documents that the transition to parenthood is accompanied by large-scale brain remodeling, including reductions in gray matter volume in cortical regions involved in social cognition and mentalizing. Current research indicates that in mothers, such structural changes may represent an adaptive streamlining of neural circuits to facilitate efficient processing of infant cues (Carmona, 2024; Hoekzema et al., 2017).

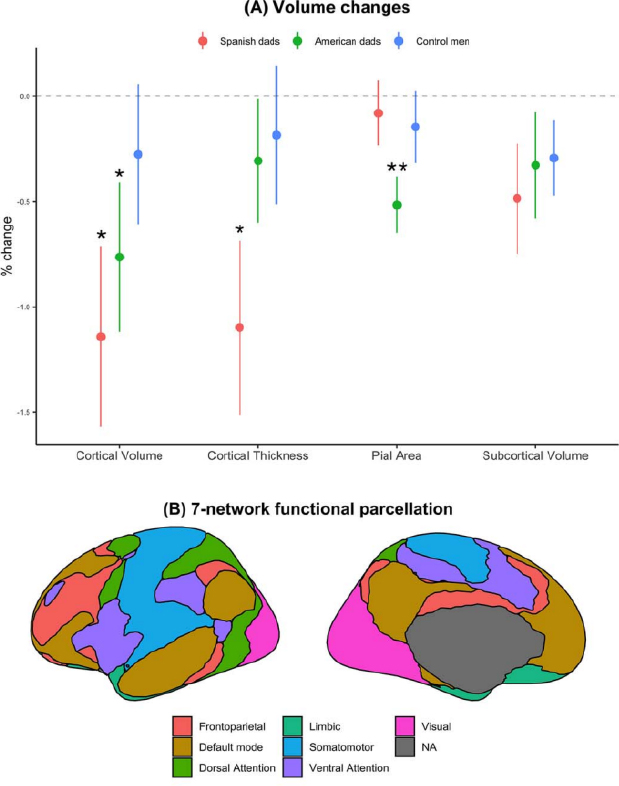

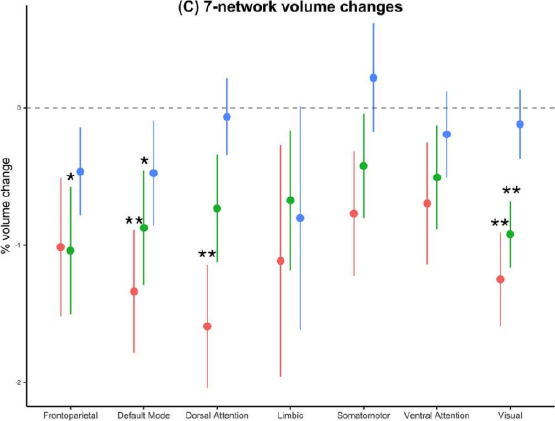

Saxbe’s work extends these observations to fathers, showing that men too exhibit changes—albeit subtler—in brain regions pertinent to caregiving and reward (see Figure 4-2). In fathers, greater reductions in cortical volume have been associated with stronger bonding to their infants and increased reports of parenting enjoyment (Martinez-Garcia et al., 2023). However, these neu-

NOTES: Percentage of brain volume changes across different groups—Spanish fathers and Californian first-time fathers, and childless men. Statistical analysis using onesample t-tests was performed to compare the percentage change in brain measures between prenatal and postnatal MRI scans. (A) shows the percentage of volume change for each brain measure. (B) presents a map of seven distinct functional networks in the brain, originally identified by Yeo and colleagues (2011), which highlight different brain regions involved in various cognitive and sensory functions. (C) displays the percentage of volume change within these seven functional networks.

SOURCES: Presented by Darby Saxbe on March 25, 2025; adapted from Martinez-Garcia et al., 2023. Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press.

robiological shifts were also linked to factors such as poorer sleep quality and heightened psychological distress, thus highlighting the dual nature of this window of plasticity: It may prime individuals for enriched caregiving while concurrently increasing susceptibility to mood disturbances if the environmental stress is high.

Moreover, emerging findings from Saxbe’s laboratory indicate differential trajectories within specific regions, such as increases in hippocampal volume related to better caregiving outcomes (Saxbe and Martinez-Garcia, 2024). This evidence suggests that even within the overall pattern of remodeling observed during the transition to parenthood, individual differences may reflect compensatory mechanisms engaged to optimize parental functioning.

Saxbe also shared findings from her research team, led by Sofia Cardenas, on brain structure and connectivity, specifically focusing on white matter. Their study examined how “early risky family environments”—characterized by coldness, neglect, and chaos—were associated with weaker white matter integrity in fathers, influencing brain connectivity during the transition to parenthood. Cardenas found that fathers from risky family environments reflect reduced neural connectivity, which in turn predicted less effective parenting (Cardenas et al., 2024). She also referenced their published research on preconception, emphasizing that fathers play a critical yet often overlooked role in shaping offspring outcomes. Saxbe cited Brian Dias’s work on pre-conception pathways, reinforcing the idea that fathers contribute to both stress and resilience in significant ways.

DISCUSSION

Reconciling Resilience Research Across Socioeconomic Contexts

Robert Valdez, professor of Family and Community Medicine at the University of New Mexico, asked how to reconcile the finding that socially disadvantaged individuals do not benefit from resilience-building factors as consistently as some datasets suggest. He emphasized the need for integration across studies and highlighted the challenge of defining resilience, questioning whether it should be understood at both societal and individual levels. Rogers emphasized the importance of considering developmental periods when comparing resilience across cohorts, explaining that findings at different ages—such as neonates versus school-aged children or adolescents—may reflect distinct processes in brain development. She cautioned against directly comparing results across studies without accounting for age-related differences in expected neural and behavioral outcomes. She also highlighted a critical factor in her research: Her cohort consists primarily of individuals living below 130 percent of the poverty line, which is a level of disadvantage often underrepresented in resilience studies. Unlike many other datasets, where severely disadvantaged individuals make up a smaller portion of the sample, her cohort’s majority population faces extreme socioeconomic hardship, allowing her team to examine resilience in deeply resource-deprived environments. Importantly, Rogers pointed out that when they excluded the most disadvantaged participants, their findings aligned more closely with existing resilience research. However, keeping this highly disadvantaged cohort in the analysis revealed a crucial insight—many conventional resilience factors do not function as expected when fundamental needs such as housing stability, food security, and educational access are not met. She argued that interventions focusing only on individual behavior or parenting strategies are insufficient without addressing the systemic barriers preventing disadvantaged families from benefiting from those efforts. Hyde noted that discrepancies in resilience research could stem from sample-specific factors, particularly the degree of disadvantage. He explained that his lab studies two different cohorts—one facing moderate poverty and another experiencing severe disadvantage—and cautioned that resilience outcomes may depend on where individuals fall on the socioeconomic continuum.

A workshop participant inquired whether research has examined the impacts of overly advantaged neighborhoods on stress resilience. Rogers acknowledged the importance of the question and noted that while some individuals in her studies might fall into the category of being overly advan-

taged, her research did not specifically analyze this population due to sample limitations. She pointed out that while definitions for social disadvantage and poverty are well established, there is no clear definition for what constitutes being “overly advantaged.” Rogers observed that in her research, positive effects of advantage appeared to follow a linear trend, whereas disadvantage showed a threshold effect before leveling off. She concluded that while the question is compelling, she is not aware of any studies directly investigating it.

Peña added that biological heterogeneity plays a role in resilience, emphasizing ongoing research into biomarkers that could help predict individual responses to adversity and improve treatment interventions. Frances Jensen reinforced the importance of biomarkers in resilience research, suggesting that advances in multimodal data may help identify thresholds for resilience and personalize intervention strategies.

Longitudinal Effects of Early Life Stress on Brain Development

Bustamante asked Peña to elaborate on how early life stress shapes neurodevelopment, potentially changing brain circuitry. Peña explained that research over decades has shown early life stress influences development in multiple ways, including altered social, emotional, and cognitive trajectories; changes in amygdala-to-prefrontal cortex connectivity; and delayed developmental milestones in rodents. These varied effects can occur simultaneously rather than being mutually exclusive. She discussed ongoing efforts to study different brain regions, cell types, and gene clusters to better understand these changes. Peña emphasized the importance of a field-wide approach, studying developmental processes longitudinally rather than focusing on single time points in adulthood. She noted that while some outcome measures eventually stabilize, early experiences have lasting effects, and a deeper understanding of brain development during critical periods could inform interventions to realign developmental trajectories.

The Neurological Mechanisms of Context-Specific Resilience

Adding to this perspective, Jensen asked if at different points during the lifespan an individual might develop resilience for one type of stressor but not another, and if this is reflected in the epigenetic changes in rodent models. Meaney cited studies by Gene Brody (e.g., Brody et al., 2013) to highlight how resilience can vary across domains within the same individual or family. He described families in which some members prosper in psychosocial realms (such as stable relationships, academic achievement, and steady employment) while simultaneously displaying vulnerability on biological measures like cardiovascular health and inflammatory responses. Meaney pointed out that

these findings challenge a “one-size-fits-all” view of resilience, arguing instead that resilience may be better understood as a pathway-dependent process. He suggested that identifying the specific mediators linking forms of adversity to particular outcomes could provide actionable targets for intervention. Building on this discussion, Hyde noted that while larger brain volume is generally linked to resilience, resilience in children remains highly domain-specific, reinforcing Meaney’s argument that resilience follows distinct pathways rather than a universal pattern (Miller-Graff, 2022). Peña acknowledged the complexity of resilience and adversity, explaining that human research is more advanced while rodent studies are still developing. She differentiated between deprivation-related stress (lack of expected experiences) and unpredictable environmental stress and noted that these different types likely influence distinct biological systems depending on the timing of exposure. While rodent models can help disentangle specific effects, she emphasized that in human development, chronic stress makes it difficult to isolate discrete impacts. Peña and Meaney underscored that resilience is not a singular static trait but a dynamic interplay of interdependent processes.

Eric Nestler inquired about brain volume changes in children and adults, asking whether there is a clear pattern of adaptive increases or decreases in brain size across different studies and conditions. Rogers addressed brain volume changes, emphasizing the importance of developmental timing. She noted that early childhood brain growth is expected, but resilience varies across environments—what is adaptive in one setting may be a disadvantage in another. To illustrate this context-dependent resilience, Rogers shared an anecdote from her research on young children in different socioeconomic environments. She explained that her team had difficulty getting two-year-olds to fall asleep in an fMRI scanner for brain imaging. Interestingly, children from more disadvantaged environments—where bedtime routines might have been less rigid—fell asleep more easily. In contrast, children from more structured home environments, who were accustomed to strict bedtime routines and specific comfort items, struggled to fall asleep in the unfamiliar setting. Rogers emphasized how this is just one anecdote that they have observed. Jensen added this might suggest highly structured environments might foster rigidity, potentially making adaptation to unexpected situations more difficult.

Potential Approaches for Resilience-Enhancing Interventions

Deanna Barch, Gregory B. Couch Professor of Psychiatry and vice dean of research at Washington University in St. Louis, asked the panel whether resilience factors, many of which are affected by early adversity, might also serve as optimal targets for intervention. She sought insights into how these mechanisms could guide efforts to promote resilience. Jensen invited Rogers to start the discussion, referencing the THRIVE framework. Rogers noted that

their research focuses on identifying the best intervention targets, particularly in caregiver behaviors that influence child resilience. Since neonates cannot actively participate in interventions, the team prioritizes factors within the caregiver’s control, including parenting practices, sleep, nutrition, stress reduction, and treatment for mental health conditions. While systemic changes at a societal level would have the greatest impact, Rogers acknowledged that individual families and clinicians will need to work within their immediate environments, as broader societal shifts take time. She emphasized the importance of identifying modifiable mediators—factors individuals can change with the right resources—to effectively promote resilience.

Hyde added to the discussion by highlighting differential susceptibility, referencing research showing that individuals with high amygdala activity tend to thrive with more resources but struggle with fewer. He argued that resilience-building should happen at multiple levels and expressed concern that relying on convenient solutions, such as apps, to address resilience could shift responsibility away from acknowledging and addressing systemic societal issues that contribute to adversity. He stressed that while individual-level interventions are important, scientists must also highlight broader societal influences that shape resilience and ensure that efforts extend beyond what individuals can control. Jensen agreed, emphasizing the need to examine whether structural aspects of society require overhauling or improvement to better support resilience. Rogers pointed to data showing that individuals who lack essential resources do not benefit from conventional resilience-building interventions. She explained that factors like unstable housing, food insecurity, and inadequate education can prevent people from gaining the expected benefits of interventions such as parenting classes. Rogers’s evidence supports the argument that resilience cannot be fostered solely at the individual level; systemic issues must also be addressed to create meaningful change.

Nestler wondered how early education programs can increase cognitive function and resilience. In response, Meaney described an early education program in Singapore, an initiative that identifies executive function as a crucial mediator of both risk and resilience, designed to strengthen these skills through structured interventions. Initially, the program faced challenges with implementation—teachers hesitated due to an already packed curriculum. However, once they introduced classroom-based games designed by experts like Clancy Blair, they noticed that students were highly engaged, making the program easier to integrate into daily lessons. Over two to three years, the initiative expanded and is now widely adopted across Singapore’s public child care system. The Singapore Ministry of Education’s sponsorship played a key role in ensuring the program’s success. Ongoing research aims to assess outcomes across multiple domains, including metabolic health, cognitive function, and socioemotional development. Meaney noted that while the games have been shown to work, the next step is to determine which children benefit the most and in what specific ways, refining future interventions accordingly.

On the other hand, Husseini Manji, professor at Oxford University, adjunct professor at Yale University, visiting professor at Duke University, and co-chair of the UK government’s Mental Health Goals program, speculated on the role of placebo responses in clinical trials for depression and anxiety. He proposed that some individuals might generate an endogenous resilience process in response to hope and support, potentially influencing treatment outcomes. He brought up the possibility that in preclinical studies environmental enrichment might be an indirect way to enhance endogenous resilience processes. So, perhaps if a treatment worked on top of environmental enrichment, that may increase the likelihood that it would exceed placebo responses in clinical trials.

Andrea Flammia, from Jiayal Media, asked whether there are studies tracking individuals who experienced traumatic childhoods but demonstrated resilience across different life stages. Flammia described experiencing lifelong trauma but building resilience through dance, singing, and music—talents she inherited from her mother. She also highlighted her strong academic performance as further proof of overcoming adversity. She emphasized the need for research examining resilience from biochemical, neural, and environmental perspectives, advocating for greater representation of successful individuals who have overcome adversity. Peña responded by noting that physical activity—particularly dance—has been shown to be a powerful resilience factor in both human and preclinical studies. She highlighted research indicating that dance promotes neurogenesis and plasticity, reinforcing resilience alongside environmental influences such as positive parenting. Flammia followed up by sharing her own academic research on exercise and brain development, expressing excitement over findings that hippocampal volume increases by 12 percent with physical activity. She reiterated the importance of showcasing successful individuals who have navigated adversity, emphasizing that such representation can inspire hope and shift perceptions about long-term outcomes.

Parenting, Emotional Regulation, and Community Responsibility

Another recurrent theme was the interplay between parental mental health and child development. Saxbe discussed the timing of resilience-related brain changes, describing a U-shaped pattern. Prebirth brain-volume decreases appear to be associated with better mental health outcomes, suggesting this reduction may be part of an adaptive process. Postbirth brain-volume increases are also linked to better mental health, indicating recovery and potential resilience following the initial decrease. She emphasized the complexity of modeling these trajectories around sensitive periods. Jon Nelson brought a personal perspective, questioning how long-term exposure to parental mental illness might affect their child’s resilience and ability to form authentic inter-

personal relationships. Rogers responded by emphasizing the protective role of supportive caregiving. She explained that even when a parent faces chronic challenges, an available emotionally regulated caregiver (which may include the other parent) could buffer adverse effects on the child.

Complementing this view, Meaney highlighted the tendency in literature to attribute poor parenting solely to maternal depression, even though many mothers with depression remain effective caregivers. To support this view, he referenced recent findings by Michelle Kee, which indicate that it is not parental depression itself but the accompanying emotional dysregulation that disrupts child development, as Rogers had mentioned earlier (Kee et al., 2023). Meaney highlighted the importance of targeting emotional regulation in prenatal interventions to better support parenting. Building on Meaney’s discussion, Hyde emphasized that parenting behaviors play a more critical role in child outcomes than depression itself. He also addressed broader societal perceptions of mental illness, pointing out that depression is widespread, affecting up to 50 percent of the population, and that mental health struggles are common across families. Hyde stressed that people do not typically choose partners based on whether their parents have mental illnesses, reinforcing the importance of open discussions to normalize these experiences and reduce stigma. He highlighted that such challenges are not abnormal but rather a shared reality for many households. Saxbe drew attention to the idea that resilience is more common than often assumed, explaining that children exposed to parental mental illness or adversity frequently do not experience negative long-term outcomes. She suggested that such experiences could foster empathy and insight within families, contributing to their emotional strength. The dialogue extended to broader societal factors as well: While individual interventions such as parenting classes can be valuable, several panelists pointed to unmet basic needs, such as stable housing, nutrition, and economic security, as critical elements that shape the resilience trajectory.

Emerging Themes in Resilience Research Noted by Workshop Participants

The panelists each offered a brief reflection that encapsulated their views. Terms such as “transformation,” “support,” “community responsibility,” “hope,” and “longitudinal intervention” were shared, collectively underscoring the multifaceted, dynamic, and context-dependent nature of resilience across the lifespan. These reflections highlighted that while scientific inquiry continues to unravel the complex biological and environmental influences on development, practical understanding remains rooted in the interplay between individual, familial, and societal resources.