Exploring the Treatment and Management of Chronic Pain and Implications for Disability Determinations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 8 Health Care System Challenges in Comprehensive Chronic Pain Management

8

Health Care System Challenges in Comprehensive Chronic Pain Management

The first session of the workshop’s second day covered how the many experiences and challenges related to chronic pain and its management affect health status, functional limitations, and medical records for adults and children. Its discussions also explored systemic barriers to delivering comprehensive, evidence-based pain care across various health care practices. The speakers were Andrea Anderson, patient advocate and advisor to the National Pain Advocacy Center; Beth Darnall, professor of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine and director of the Stanford Pain Relief Innovations Lab at Stanford University Medical School; Julie Fritz, distinguished professor of physical therapy and athletic training at the University of Utah; and V. G. Vinod Vydiswaran, associate professor of learning health sciences and associate professor of information at the University of Michigan.

PATIENT EXPERIENCES WITH SOCIAL SECURITY DISABILITY

Andrea Anderson became a chronic pain sufferer after she received a surgery planned for someone else rather than the small surgery she was scheduled to have on her lower back. She was fortunate, though, to receive excellent pain management in her community from a pain specialist, enabling her to raise her family and maintain her professional and social obligations.

High-impact chronic pain affects 10.6 million people, or 20 percent of the chronic pain population in the United States (Pitcher et al., 2019). High-impact chronic pain results in substantial restrictions in daily activi-

ties, such as being able to work, go to school, or complete daily chores, and typically lasts three months or longer (Pitcher et al., 2019). “It is the kind of pain that feels like you cannot spend another day inside your body—the kind that can take your life hostage if you cannot find a way to manage it,” said Anderson.

To prepare for her presentation, Anderson crowdsourced information via multiple social media platforms from hundreds of chronic pain patients who receive or would like to receive Social Security disability. Responses to the first question she asked, about barriers to care, included the following:

- Challenges with qualifying and acceptance, with the average application being denied multiple times, and having to hire an attorney to finally be granted needed services. The average wait for an application review is now 14 months, up from 2–4 months, and the average hold time to speak to a person is now 4.5 hours. Every respondent said their calls are often terminated before they reach a human.

- Lack of access to clinicians and specialists, particularly in health care deserts such as rural communities. Patients on disability in these communities often rely on disability van services to get them to appointments, but many of these programs operate only one day a week and not on the day their clinicians are in the office.

- Insufficient provider networks, as many physicians do not take Medicare or Medicaid patients. In addition, some plans limit patients to seeing one provider per day, which can be a problem for a patient that relies on hired transport to get them to their appointments.

- Financial constraints, with disability payments inadequate for current economic realities. This can create housing instability, a significant health stressor.

- Difficult pharmacy access, particularly if mobility is a challenge or during a natural disaster when patients report having trouble accessing their medications.

Taken together, these barriers usually increase disability-related delays in care that can affect disease progression, worsen health and symptoms, impede an individual’s personal agency and independence, and strain family relationships.

Anderson then offered recommendations from the patient community to the Social Security Administration (SSA):

- Increase staff and training to improve wait time for applications to acceptance and time spent on phone and in-person visits.

- Increase reimbursement rates to clinicians who treat people with complex conditions and persistent pain.

- Allow patients to see more than one provider on a single day.

- Allow patients to store emergency medications in case of disaster.

- Increase mail-order pharmacy access.

- Increase cost of living adjustments beyond Medicare premium increases.

- Provide more low-cost housing and transportation options.

ACCESSIBLE BEHAVIORAL PAIN CARE

What is common throughout the journey from acute pain to chronic pain and then into the Social Security disability determination process is a need for behavioral treatment to support the individual, address their pain more completely, and mitigate some of the symptoms and stresses that co-occur throughout this journey, said Beth Darnall. “We know that people who receive intensive behavioral pain treatment do better, but these intensive treatments are inaccessible, and most people are left without [them],” she said. She added that briefer treatment can offer people many benefits and can be administered across a variety of settings.

Darnall noted the International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as both a noxious sensory and emotional experience, highlighting the importance of treating both the physical and psychological aspects of chronic pain. However, poor access to behavioral treatment leads to incomplete treatment and overmedicalization of chronic pain. In addition, the distress people with chronic pain experience amplifies the pain, allows the pain to progress, and leads to greater disability. While federal agencies and nonprofit organizations have called for better integration of behavioral treatment into pain care pathways and research has shown that integration leads to cost savings (Lanoye et al., 2017; Melek et al., 2018), access to and uptake of behavioral treatment is poor.

Behavioral pain treatment, Darnall explained, is delivered one-on-one or in small groups. Often it involves 16 hours or more of treatment time, during which individuals learn what worsens pain and which daily choices and skills offer the most relief, gain skills and resources to help modulate pain, and create action plans (Darnall, 2019). Barriers to behavioral treatment include the significant time commitment, insurance and copay limitations, work and family obligations, proximity to the treatment site, and a lack of trained clinicians (Darnall et al., 2016). The rise of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic has helped somewhat with the proximity issue, she added.

There are also health care system barriers, said Darnall. Often, the health care system emphasizes medical approaches and de-emphasizes behavioral approaches. In addition, reimbursement for behavioral treat-

ment is often insufficient to fully incentivize both adoption and delivery of behavioral treatment and deploy the resources to implement behavioral treatment.

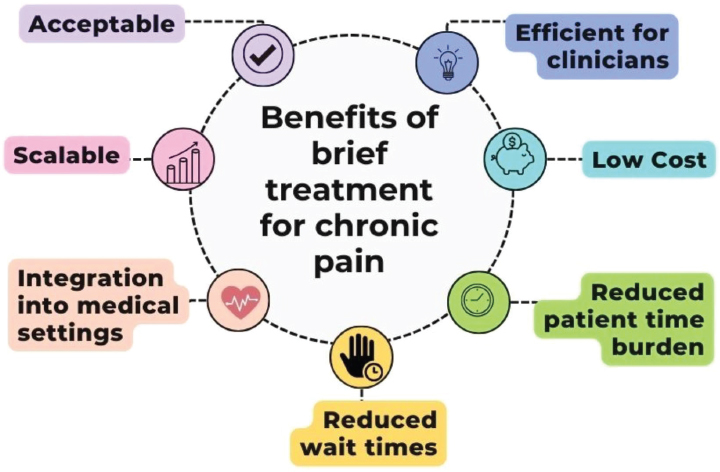

To overcome these barriers, Darnall said the solution is to implement brief treatment approaches. While these approaches may not benefit everyone, they would provide all individuals with chronic pain at least a minimal level of care. She noted there are several benefits of brief treatment for chronic pain (Figure 8-1; Darnall, 2025b), and evidence supports the use of six different brief behavioral treatments for addressing chronic pain (Darnall, 2025b).

Of the six interventions supported by evidence, only two have been adopted widely, largely because clinician training systems are needed to support the adoption and sustainability of these interventions. One of the adopted interventions is brief cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for veterans in primary care. It comprises six 30-minute sessions that are integrated with an individual’s primary care visits. The second intervention is Empowered Relief®, the only applied intervention adopted widely for nonveterans (Darnall et al., 2021; Ziadni et al., 2021). Empowered Relief® consists of a two-hour didactic session during which people learn three pain management skills and complete a personalized plan. Participants receive access to an app they can use to help them follow their plan.

SOURCE: Darnall presentation, April 18, 2025.

Darnall highlighted the results from several clinical trials comparing this 1-session intervention to an 8-session, 16-hour CBT-based approach, showing that the 1-session intervention produced results equivalent to those produced by the more extensive approach that lasted for at least 6 months (Darnall et al., 2024). There are now some 1,600 certified Empowered Relief® instructors in 30 countries, with 15,000 people visiting the Empowered Relief® app each month. Darnall said most types of licensed clinicians may become certified (Davin et al., 2022; Darnall et al., 2023).

Darnall said providing access to evidence-based behavioral pain treatment is essential, and individuals with chronic pain should receive low-burden behavioral pain treatment early and throughout the Social Security disability determination process. She recommended SSA support research on brief behavioral pain interventions; consider relevant, unsolicited proposals that would relieve pain care gaps; and consider interagency policy advocacy to improve reimbursement across provider types. Finally, she noted that digital interventions integrated into a learning health system could help scale access to behavioral interventions nationally.

HEALTH CARE SYSTEM CHALLENGES IN COMPREHENSIVE CHRONIC PAIN MANAGEMENT

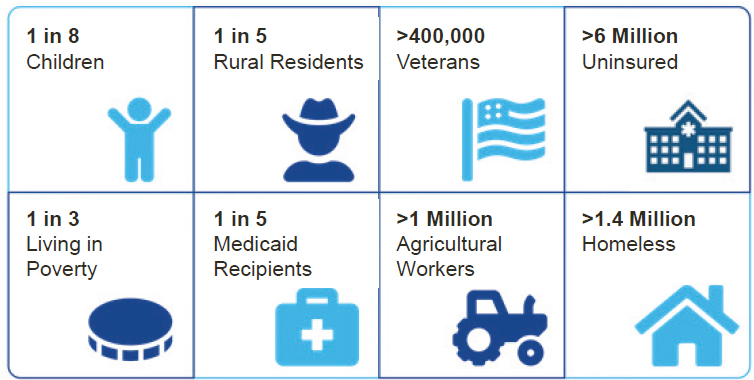

Julie Fritz cited data showing the percentage of adults with chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain increases as the place of residence becomes more rural and family income levels decrease. Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), which serve medically underserved communities and provide services to all comers on a sliding fee scale, could help meet the demand for chronic pain management services for rural residents and individuals with incomes below the federal poverty line. Fritz noted that in 2023, FQHCs served about 10 percent of the U.S. population (Figure 8-2).

One challenge for FQHCs is a shortage of clinicians trained to provide nonpharmacologic pain treatment for individuals living with chronic pain. FQHCs are attempting to address this shortage using telehealth, particularly in rural settings, though patient access to the necessary technology can be limited. Fritz and her colleagues in Utah have been implementing telehealth for people with chronic pain in the state’s rural and underserved urban areas.

She listed several lessons learned in partnering with FQHCs for telehealth pain care (Table 8-1). For example, experience demonstrated the usefulness of incorporating motivational interviewing to produce behavior change and help patients develop coping skills, and to deliver linguistically and ethnically competent care to the state’s rural communities.

SOURCE: Fritz presentation, April 18, 2025.

THE ROLE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND NATURAL LANGUAGE PROCESSING IN CHRONIC PAIN AND DISABILITY DETERMINATIONS

V. G. Vinod Vydiswaran spoke about the use of artificial intelligence and medical natural language processing (NLP) to extract information from clinical notes in electronic health records (EHRs) that could be helpful for finding those at risk for high-impact chronic pain. In general, he explained, these data extraction methods are looking for computable phenotypes, or key characteristics about a patient that can be derived computationally, in the massive amount of data in an EHR. One study he and his collaborators conducted used NLP to identify risky alcohol use from clinical notes. In this study, NLP identified three times more patients with risky alcohol use than had been identified with International Classification of Diseases codes (Vydiswaran et al., 2024). NLP identified 87 percent true positives versus the 29 percent identified by International Classification of Diseases codes, the existing standard approach. Vydiswaran said researchers have developed NLP-based methods for extracting information from the EHR on social determinants of health, including alcohol use, tobacco use, drug use, and employment status, as well as disease state, medication use, and changes in those over time (Lybarger et al., 2023). In particular, deep neural network models have proven better at extracting this type of information than traditional machine learning–based models.

TABLE 8-1 Lessons Learned Partnering with Federally Qualified Health Centers

| Issues Encountered | Facilitators Identified | Strategies Implemented | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Access to Care |

|

|

|

| Adaptations to PT Interventions |

|

|

|

| Patient-PT Working Alliance |

|

|

|

| Culturally Competent Care |

|

|

|

NOTES: mHealth = mobile health; PT = physical therapy.

SOURCE: Fritz presentation, April 18, 2025.

Vydiswaran noted that chronic pain has been described in EHRs using structured data, such as pain intensity, treatment modalities, diagnostic codes, and interventions. Methods using these data, however, can only identify upward of 80 percent of individuals with chronic pain. In addition, while large language models have improved significantly in recent years, biased data, such as clinicians’ dismissal of Black women’s pain in clinical notes, beget biased models. There is active research on developing validated intersectionality-aware artificial intelligence models that can determine phenotypes such as pain.