Exploring the Treatment and Management of Chronic Pain and Implications for Disability Determinations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 5 Considering Best Practices and Clinician Perspectives on Chronic Pain Treatment and Management in Children

5

Considering Best Practices and Clinician Perspectives on Chronic Pain Treatment and Management in Children

In this session participants discussed best practices and methods of categorizing chronic pain and advancements in the treatment, management, and measurement of children’s chronic pain levels. They also highlighted special considerations in how medical providers approach treatment of different severities in chronic pain in children. The speakers were Casey Cashman, director of the Pediatric Pain Warriors Program at U.S. Pain Foundation; Tonya Palermo, professor and vice chair for research, anesthesiology, and pain medicine at the University of Washington; Stefan Friedrichsdorf, medical director of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative and Integrative Medicine at Benioff Children’s Hospitals in Oakland and San Francisco; and Laura Simons, professor of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine at Stanford University Medical School.

LIVING WITH MULTIPLE SERIOUS HEALTH CONDITIONS, INCLUDING COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME

Casey Cashman, who said she does not remember a time when she was not dealing with strange medical issues, said having a family who believed in her and a pediatrician who did not dismiss what she was going through made all the difference. Today, while she deals with several serious health conditions, including complex regional pain syndrome, people tell her she does not look like she is in pain. The truth is that pain is invisible, and just because someone is smiling does not mean they are not struggling, Cashman said. She has been fortunate to have access to experimental treatments, such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy and ketamine infusions, but

these are expensive, rare, and not available to everyone, so many people go without.

Cashman stressed how important it is to believe what children are saying about their pain, to support them and their families, and to not make them fight for the care they need. “We need to change the way our health care system sees pain, especially in young people, because if we can change the pain journey for children, we can change their whole life,” she said. Having accepted that she will never be pain free, she has hope that life is manageable and that she can have a life with joy, purpose, and love.

PSYCHOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS FOR YOUTH WITH CHRONIC PAIN

Tonya Palermo listed the four transformative goals of the Lancet Child and Adolescent Health Commission, developed for the field of pediatric pain:

- Make pain matter by improving equity, eliminating stigma, and making pain matter to everyone, including health professionals, policy makers, funders, researchers, clinicians, and society at large.

- Make pain understood by improving knowledge of all types of pain across the life course and integrating biological, psychological, and social elements.

- Make pain visible by standardizing assessments for pain and determining pain status in every child.

- Make pain better by avoiding unnecessary pain, preventing the transition from acute to chronic pain, and striving for universal access to effective pain treatments for children and adolescents.

Palermo said there are beliefs and biases about childhood pain that reinforce stigma and delay treatment, particularly the tendency to disbelieve children and adolescents about their pain experience that can make the journey to find pain care more challenging (Wakefield et al., 2022). She noted how important it is to recognize the potential long-term effects of adolescent chronic pain on adult educational, vocational, and social outcomes. Additional research has shown that someone with chronic pain during adolescence is less likely to receive a high school diploma, bachelor’s degree, and employer-provided insurance benefits, and more likely to receive public assistance or disability payments, become pregnant or a parent earlier, and have lower relationship satisfaction as young adults (Murray et al., 2020).

A wide range of neurobiological, emotional, social, family, and health behavior vulnerabilities influence childhood chronic pain. Palermo said

these factors predict pain during childhood but also chronic pain maintenance into adulthood, with longitudinal studies showing that 30 to 70 percent of children with pain continue to experience it into adulthood. Therefore, prevention and management of chronic pain must begin in childhood, Palermo said, and her focus as a psychologist has been on identifying and targeting vulnerabilities that psychological treatment approaches can address (Palermo, 2020). She explained that, compared to those without pain, children and adolescents with chronic pain have three times the increased risk of developing mental health conditions, including anxiety and depressive disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, suicidality, and substance use disorder.

Fortunately, said Palermo, robust evidence supports the use of psychological therapies to manage chronic pain in childhood, most of which are based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Fisher et al., 2018). CBT-based therapies teach children and families skills for self-managing and coping with pain and focus on enhancing functioning in daily life, including supporting re-engagement in school, social life, and physical activity. Unfortunately, only 5 percent of children and adolescents with chronic pain will receive a psychological intervention, largely because of a shortage of interdisciplinary pediatric pain clinics and pain psychologists, delayed referral to subspecialty care, and long waiting lists for pain services.

To address the availability problem, Palermo developed and tested an internet-delivered, family-based CBT program, WebMAP, for reducing adolescent pain-related disability and depression and anxiety symptoms (Palermo et al., 2009; Walker et al., 2021). This program improved parents’ perceptions of the effects of chronic pain and helped change parental protective behaviors. Specialty clinics have implemented a mobile app version of WebMAP and achieved high adoption and sustainability (Palermo et al., 2020). The free app, also available in a Spanish version, is available in both Apple and Google app stores.

While schools would be an ideal setting for implementing this type of intervention, Palermo said the lack of standardized guidelines and resources for school personnel to effectively support students with chronic pain is a major impediment. Researchers have conducted few school-based interventions, but Palermo said there are opportunities to embed pain education and intervention in existing school-based mental health programs, such as mindfulness courses and adverse childhood experience training.

Palermo noted the need to make low-cost, low-intensity interventions universally available to help children with chronic pain in multiple settings of care. “Early intervention and prevention are really key to having a population-level impact on pain,” she said.

PREVALENCE OF CHRONIC PAIN IN CHILDREN

Stefan Friedrichsdorf said 3 to 5 percent—444,000 to 740,000—of U.S. children and adolescents develop significant pain-related disability and need intensive pain rehabilitation (Huguet and Miró, 2008). Between 12 and 20 percent of pediatric inpatients show features of chronic pain (Friedrichsdorf et al., 2015; Postier et al., 2018), he added. Primary chronic pain disorders in children include chronic migraines and tension-type headaches, chronic abdominal pain, and widespread chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Friedrichsdorf said surgery is usually not recommended to address chronic pain in children and adolescents. In fact, there are data showing that adolescents who had surgery for lumbar disk herniation experienced worse pain and other health complications in adulthood (Lagerbäck et al., 2021; Ruehr et al., 2024). He noted that children in pain develop more stress and anxiety, which causes a vicious cycle of more pain, triggering more stress and anxiety and more pain. Eventually, these children develop avoidance behaviors that make them less active, then lose conditioning and develop a faster heart rate when they are active.

An important factor in treating children with chronic pain, said Friedrichsdorf, is that these children hear their pain is real, as young people often experience pain for over 2 years before getting a diagnosis (Neville et al., 2020).

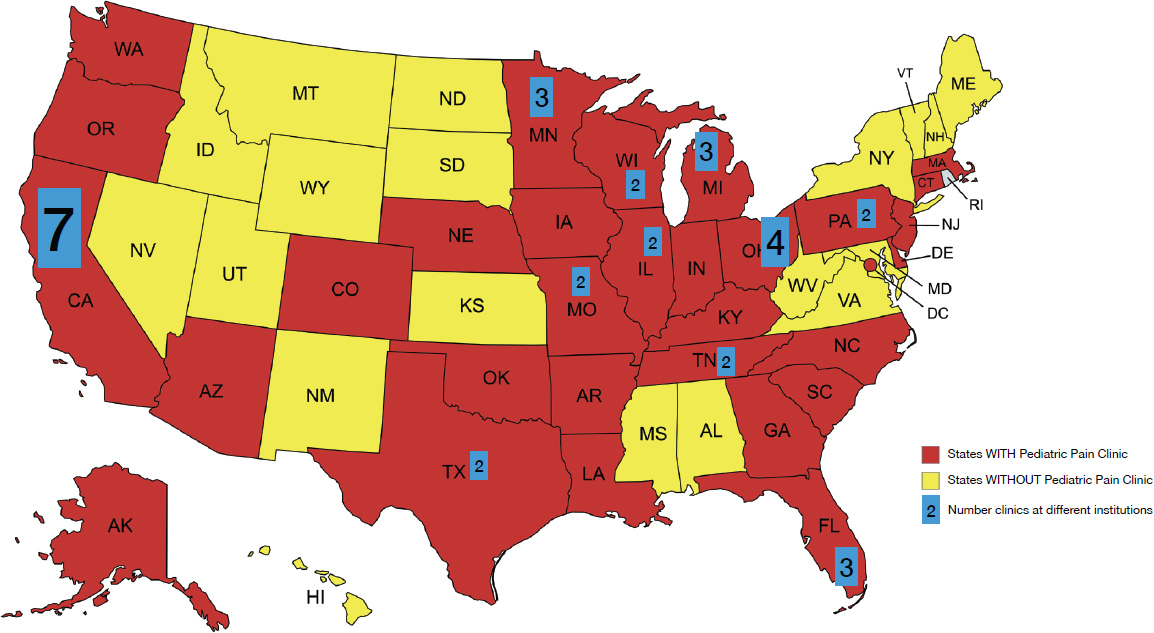

Friedrichsdorf explained that a rehabilitative pediatric pain clinic approach includes physical therapy, integrative medicine techniques, psychotherapy, family coaching, and normalizing life activities such as sleeping, having fun, and attending school full time. There is little emphasis on pharmacotherapy, particularly using opioids. This cost-effective approach enables many children treated in pediatric outpatient pain clinics to return to everyday function, with some needing additional intensive treatment such as additional rehabilitative day treatment or an inpatient program (Evans et al., 2016; Friedrichsdorf et al., 2016; Mahrer et al., 2018; Simons et al., 2018). However, there are fewer than ten pediatric programs in the United States that offer this approach. In fact, there are only 60 self-declared pediatric pain clinics in 32 states and the District of Columbia (Figure 5-1).

CONSIDERING INNOVATIVE APPROACHES FOR THE TREATMENT OF CHRONIC PAIN IN CHILDREN

Laura Simons said one way to treat young people more efficiently, given the shortage of pediatric pain specialists and pain clinics, is to use brief screening tools to triage risk level (Simons et al., 2015; Heathcote et al., 2018). This allows children to get into appropriate treatment pro-

SOURCE: Friedrichsdorf presentation, April 17, 2025. Based on data from Palermo, T. “International Directory of Pediatric Chronic Pain Programs.” Published December 23, 2024 at http://childpain.org/index.php/resources.

grams. One program she has been using is the two-hour virtual Empowered Relief®1 class adapted for youth, which helps validate the pain these children are experiencing, teaches them about how the brain processes pain, provides them with simple daily skills, and helps them create a personalized plan for long-term relief.

The Empowered Relief® program adapted for youth prepares children who need more intensive interventions. One intervention she has been working on is Graded Exposure Treatment (GET) Living, which integrates pain psychology and physical therapy to help young people regain their functionality (Simons et al., 2020). This intervention has also been modified to deliver GET Living digitally and to incorporate virtual reality into pain rehabilitation as a means of increasing engagement in what can be a boring, uncomfortable, and painful experience (Griffin et al., 2020; Simons et al., 2024).

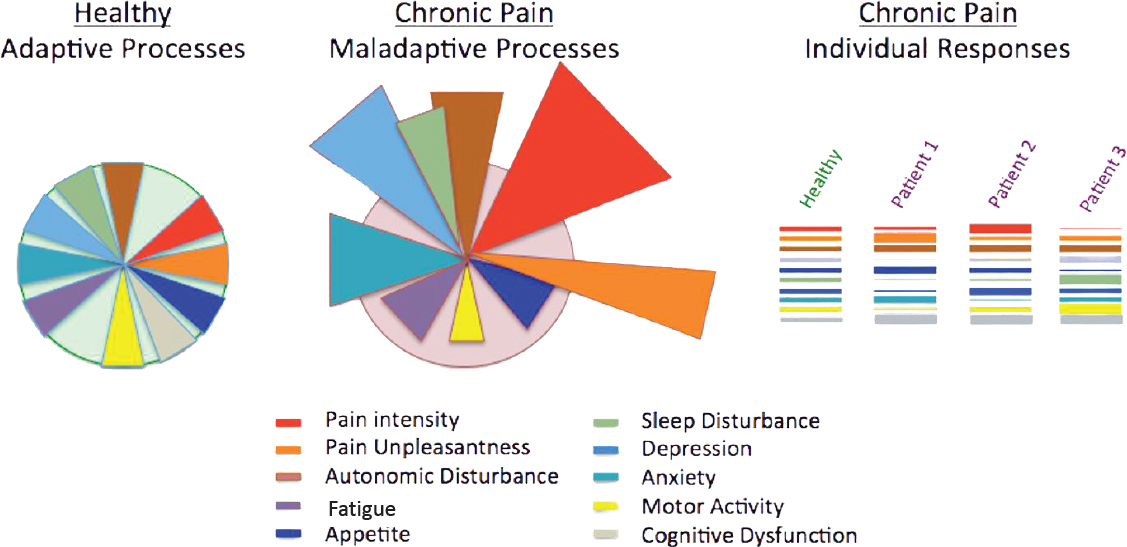

As Friedrichsdorf noted, some patients will need more intensive rehabilitation programs. However, said Simons, even with more intensive programs, her data show that between one-third and half of young people continue to experience chronic pain, though with improved functionality (Simons et al., 2013, 2018). The challenge is emphasizing different aspects of an intensive interdisciplinary approach to pain treatment depending on an individual’s particular need (Figure 5-2). “I think there is so much promise in our ability to use predictive analytics and patient-centered precision care to have a better understanding of who needs what,” she said.

Simons said a young person’s journey with chronic pain is long and complex. It is critical, she said, that young people can access low-burden, scalable behavioral health interventions, and that current innovative approaches to screening and comprehensive assessment can inform individualized treatment approaches. A meaningful subgroup of patients will require intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment, which is of limited availability today, she acknowledged.

___________________

1 https://empoweredrelief.stanford.edu/ (accessed June 19, 2025).

SOURCES: Simons presentation, April 17, 2025. Adapted from Borsook and Kalso, 2013.

This page intentionally left blank.