Exploring the Treatment and Management of Chronic Pain and Implications for Disability Determinations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 10 Emerging Research on New or Improved Methods for Measuring and Managing Chronic Pain

10

Emerging Research on New or Improved Methods for Measuring and Managing Chronic Pain

This session provided an overview of recent research on new or improved approaches to measuring and managing chronic pain. The speakers were Sean Mackey, Redlich Professor of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine, chief of the Division of Pain Medicine, and director of the Stanford Systems Neuroscience and Pain Lab at Stanford Medical School; Nathaniel Schuster, associate professor of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego; Konstantin Slavin, professor, chief of section, and fellowship director for stereotactic and functional neurosurgery in the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Illinois Chicago; John Chae, executive vice president and chief academic officer for the MetroHealth System and professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine; Ming-Chih Jeffrey Kao, clinical associate professor of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine at the Stanford Pain Management Center; and Christin Veasley, pain research advocate and cofounder of the Chronic Pain Research Alliance.

THE FUTURE OF CHRONIC PAIN ASSESSMENT

Sean Mackey said patient-reported outcomes are the way researchers and clinicians typically measure pain, but the 0 to 10 pain intensity score is overly simplistic, is only moderately consistent, and does not account for a person’s biopsychosocial, holistic aspects. What is needed, said Mackey, is a better way of capturing daily fluctuations in pain, tools reflecting the true lived experiences of those with chronic pain, and approaches to integrate the patient’s perspective with objective measures.

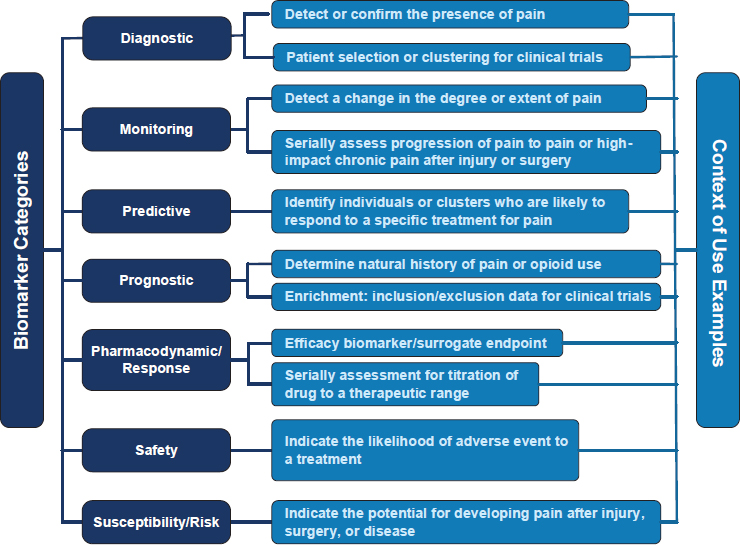

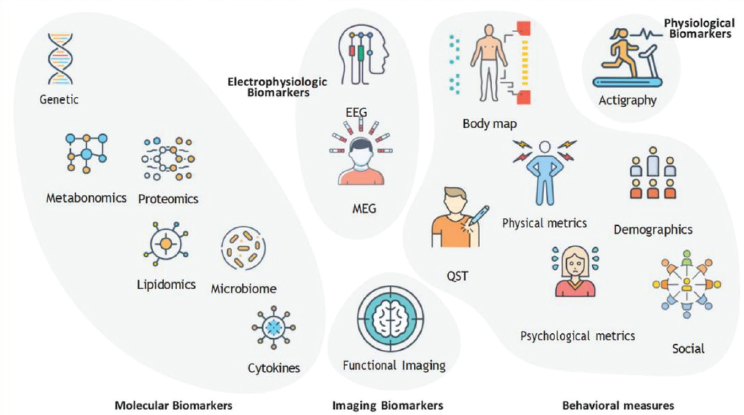

Mackey noted there are different types of biomarkers, including diagnostic, predictive, prognostic, and safety (Figure 10-1; Mackey et al., 2019). Researchers are developing multi-omic biomarkers that use genetic, proteomic, metabolomic, and others, but none have yet been established as reliable biomarkers of chronic pain. The hope is that biomarkers can someday distinguish between different types of pain—inflammatory versus neuropathic pain, for example—and predict which treatment will work best for a given individual. While this is an emerging area of research, it is one about which Social Security Administration (SSA) adjudicators will have to become knowledgeable.

Another active area of research is investigating whether wearable technology can accurately monitor pain. Changes in activity and sleep patterns, which many digital watches now measure, might be linked to pain. Mackey predicted there will likely be rapid advances in this area, given the necessary sensors are inexpensive and widely used. Such devices may be able to provide SSA with real-world evidence of pain’s functional limitations. Studies

SOURCES: Mackey presentation, April 18, 2025; Mackey et al., 2019. Copyright © 2019. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of The International Association for the Study of Pain. CC BY 4.0.

are also ongoing in quantitative sensory testing to measure pain thresholds and sensitivity, identify pain mechanisms, and match patients to targeted therapies. Quantitative sensory testing may be able to provide SSA with objective evidence of abnormal pain responses, noted Mackey.

Neuroimaging to visualize pain is one of the most interesting research areas to Mackey. Spinal cord and brain magnetic resonance imaging and positive emission tomography have produced pain signatures, while peripheral nerve imaging has identified pain sources. He noted that these methods are not yet at the point where they can tell if someone’s pain is disabling, but research is heading in that direction (Davis et al., 2017).

What is clear is that no single biomarker will provide all the necessary information (Mackey et al., 2025). “It is not possible to completely encapsulate the experience of pain into one type of biomarker, and we need to fold these together,” said Mackey. What is needed, he said, are composite, multimodal biomarker signatures, most likely enabled by artificial intelligence, to overcome the failure of electronic health records to integrate data and make them more actionable (Figure 10-2; Davis et al., 2020).

SOURCES: Mackey presentation, April 18, 2025; Mackey et al., 2025. Copyright © 2025, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. on behalf of American Society of Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine.CC BY 4.0.

EMERGING PHARMACOTHERAPIES FOR PAIN AND HEADACHE DISORDERS

Nathaniel Schuster discussed several emerging pharmacotherapy options for treating pain. He started with sodium channel inhibitors, the first of which the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved to treat moderate to severe acute pain. Sodium channel receptors, he explained, are highly expressed in pain-sensing neurons in the periphery and represent a drug target that might avoid central nervous system side effects.

Another class of drugs under development targets the transient receptor potential channels involved in pain sensation, explained Schuster. One drug candidate was well tolerated in a phase 1 clinical trial and is currently in a phase 2 study for acute migraine. Studies of a third class of molecules, known as Lyn tyrosine kinase inhibitors, have shown that they can reduce pain and are well tolerated (Tiecke et al., 2022).

Compounds found in marijuana, known as cannabinoids, may be useful as chronic pain treatments. Schuster noted that a 2017 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine stated there was conclusive or substantial evidence that cannabis is effective for treating chronic pain in adults (NASEM, 2017). Psychedelic compounds, including LSD and psilocybin, are also the subject of pain treatment research and have shown some promise in treating certain types of chronic pain (Goel et al., 2023; Lyes et al., 2023; Askey et al., 2024).

DEVELOPMENTS IN NEUROMODULATION FOR PAIN

Konstantin Slavin explained that neuromodulation aims to alter nerve activity by delivering a stimulus, such as an electrical pulse or chemical agent, to restore normal function and relieve symptoms. Neuromodulation does not address the underlying problem causing pain, but it changes the way patients feel their symptoms and helps them regain function.

Today, implanting a neuromodulation device is the most common surgical intervention for treating chronic pain, said Slavin. These devices can provide significant pain reduction without opioids. Neuromodulation is customizable and adjustable and has minimal side effects compared to medications. Device implantation involves a minimally invasive procedure that can be reversed. FDA has approved a long list of devices, allowing clinicians the ability to select the right device for the right indications.

Slavin said a new direction in neuromodulation is looking at its utility outside of stimulating specific regions of the spinal cord. The newest devices can stimulate the dorsal root ganglion and treat complex regional pain syndromes (Deer et al., 2013). Burst-mode devices, which deliver pulsed rather than continuous stimulation, work on both the somatic pain system

that localizes pain and the medial pain pathways involved in the emotional processing of pain (De Ridder et al., 2013). One limitation of this approach is that some people develop tolerance to the stimuli.

PERCUTANEOUS PERIPHERAL NERVE STIMULATION

John Chae discussed his work developing percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation to treat shoulder pain after stroke. With electrodes anchored in the muscle surrounding a patient’s shoulder, the nerve to the muscle is stimulated, causing it to contract and provide feedback to the central nervous system. This feedback is believed to modulate central sensitization. After 30 to 60 days, he removes the electrode, but the therapeutic effect—a significant reduction in shoulder pain—remains (Chae et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2014).

Based on these results and others, Chae said that if central sensitization is the convergent mechanism behind chronic musculoskeletal pain in general, and if percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation reduces shoulder pain via modulation of central sensitization, then percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation should reduce musculoskeletal pain in general. In fact, a recent review of prospective studies concluded that percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation for up to 60 days “provides durable clinically significant improvements in pain and pain interference. Similar efficacy across diverse targets and etiologies supports the broad applicability for use within the chronic pain population using this non-opioid technology” (Pritzlaff et al., 2024). Another recent “real-world” retrospective review found that 71 percent of over 6,000 patients experienced greater than 50 percent pain relief and improved quality of life (Huntoon et al., 2023). The device received FDA clearance in 2016 and has been placed in over 36,000 patients.

Chae also briefly discussed high-frequency blocks as a treatment for pain. This technique, which delivers high-frequency stimulation to block nerve impulses, was first developed to treat post-amputation pain and received FDA clearance in 2024 (Kapural et al., 2024).

EMERGING DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES FOR MEASURING AND MANAGING CHRONIC PAIN

Ming-Chih Jeffrey Kao provided a high-level survey of emerging digital technologies for measuring and managing chronic pain. In 2023 FDA approved the first device for quantitative assessment of nociception during surgery. This device features a finger probe that gathers information on a patient’s heart rate, skin moisture, movement, and temperature and produces a composite objective acute pain score. In a clinical trial, patients whose anesthesia was guided by this device received 30 percent less opioid

pain medication during surgery and experienced fewer episodes of low blood pressure (Meijer et al., 2019). Kao noted that FDA’s approval set a precedent for objective acute pain measurement devices, which should encourage further innovation.

Turning to the subject of pain management, Kao noted that in 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began covering digital mental health treatment, a category of prescription digital therapeutics that require FDA clearance as a medical device. Digital mental health treatment has the potential, said Kao, to address the worsening health care worker shortage the United States faces over the next decade. Kao noted that disability-focused software is not eligible for FDA’s Breakthrough Devices Program.

There are several digital therapeutic solutions for home physical therapy under development. A clinical trial of one such device found that an eight-week digital physical therapy program improved pain and pain interference in individuals with low back pain that was equivalent to conventional in-person physical therapy, though the digital group had half the dropout rate. Kao said the majority of digital rehabilitation therapeutics rely on advanced computer vision to detect the patient’s movements using pose estimation algorithms (Stenum et al., 2024). He noted that none of the eight commonly used pose estimation algorithms were trained using data that included disabled individuals, though studies are ongoing to address this shortcoming.

Kao said virtual reality is also emerging as a powerful tool for pain management without pharmaceuticals. In a clinical trial, a 56-day virtual reality program comprising daily sessions lasting 2 to 16 minutes each produced significant reductions in pain intensity and pain interference in individuals with low back pain that lasted for up to 24 months (Maddox et al., 2023).

While promising alternatives to medication, Kao said hardware-based digital therapies face significant accessibility hurdles, including cost, physical usability challenges, and inconsistent insurance reimbursement. Addressing these barriers, he said, is crucial to achieving equitable access.

Kao discussed the use of large language models, such as ChatGPT, for summarizing information in electronic health records. In one recent study, ChatGPT 4.0 summaries of radiology reports, patient questions, progress notes, and doctor–patient dialogue were deemed to be either equivalent or superior compared with summaries from medical experts (Van Veen et al., 2024). In contrast, an earlier study using ChatGPT 3.5 found it was prone to generating incorrect summaries (Tang et al., 2023). The lesson here is that humans must be in the loop to ensure safety and accuracy. Kao noted that large language models can complement natural language processing and artificial intelligence systems by providing better context, summaries, and decision support.

CO-CREATING PAIN THERAPEUTICS: WHERE INNOVATION MEETS LIVED EXPERIENCE

In her presentation, Christin Veasley addressed the reasons new therapeutics and innovation are needed for chronic pain treatment. She noted that deciding on treatment is complicated for an individual who lives with chronic pain, making it important that these decisions are made in partnership between clinician and patient. In making these decisions, factors such as the emotional toll, financial burden, and social impact are also involved.

Moreover, while there are many therapeutic options available, patients and clinicians alike have little or no evidence to guide them in making an informed decision, leading to a trial-and-error approach that can be costly, both financially and emotionally, and take an extreme physical toll. In her case, finding the right treatment for her chronic pain took 6 years with 6 clinicians, 20 to 25 hours a week, and tens of thousands of dollars a year trying dozens of medications and dozens of nonpharmacologic interventions. “I lost years of my life to ‘let’s see if this works,’” said Veasley.

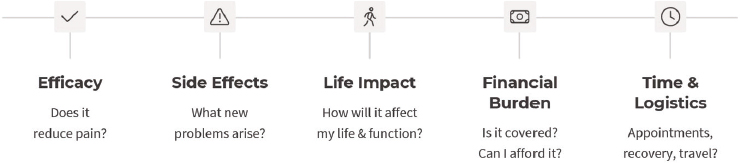

An underappreciated aspect of this type of journey that many people living with chronic pain face is the complexity of the risk-benefit decisions they must make for every single treatment they try (Figure 10-3). “It is not just the efficacy; it is also about the side effects,” said Veasley. Other considerations include how the treatment may impact a person’s ability to function, the financial burden, insurance coverage, appointment scheduling, and recovery time.

Complicating these decisions further, said Veasley, is the fact that many people have multiple pain conditions or multisite body pain along with comorbidities such as sleep disorders, mood disorders, cognitive impairment, and fatigue. As a result, treatments often need to be multimodal, and a risk-benefit analysis goes into each aspect of a treatment plan. In addition, it’s likely that people have other chronic diseases, since 6 in 10 U.S. adults have at least one chronic illness, and 4 in 10 have two or more. Treatment choices must then factor in heart disease or diabetes. “As you have more

SOURCE: Veasley presentation, April 18, 2025.

conditions or you are considering additional treatments, the decision tree grows exponentially,” said Veasley. “Then we are in this place where it is almost impossible to weigh all the risks and benefits simultaneously to identify the best overall treatment plan.”

The goal, said Veasley, is to end the trial-and-error era, and that requires better data to identify which treatments will work for which patients and to develop predictors of success. It also requires studying additive effects of treatment combinations and meaningful metrics to help individuals prioritize the outcomes that matter most to them. In addition, too many treatments have been evaluated only over the short term, with little grasp as to how they work over a person’s lifetime.

Key to addressing all of these challenges and complexities will be to partner with patients throughout the entire research and development cycle, starting at the very beginning with designing new and innovative therapeutics that take patients’ critical needs and input into consideration. This partnership should continue all the way through the research lifecycle, including patient-centered study design, execution of clinical trials, and implementation of new therapeutics (Haroutounian et al., 2024). “People are more likely to adopt solutions they help create, for that builds trust—a critical issue in the research landscape,” said Veasley. Regarding development of novel diagnostics for chronic pain, she noted that while the goal of pain research is to garner objective data, the experience of chronic pain remains subjective, and patients’ reports of their physical and emotional experiences should be prioritized. Also imperative is to design novel diagnostics and treatments that are accessible, non-intrusive, affordable, and easy for everyone to use.