Exploring the Treatment and Management of Chronic Pain and Implications for Disability Determinations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 4 Methods and Metrics for Chronic Pain Assessment in Adults and Children

4

Methods and Metrics for Chronic Pain Assessment in Adults and Children

The workshop’s second session discussed best practices and methods of categorization for chronic pain; advances in treating, managing, and measuring chronic pain levels in children and adults; and how the assessment of chronic pain connects to assessments of function, performance, behavior, and disability. The four speakers were Deb Constien, a person with lived chronic pain experience; Steven George, the Laszlo Ormandy Distinguished Professor of orthopedic surgery at Duke University; Carole Tucker, professor and associate dean of research at the University of Texas Medical Branch; and Anna Wilson, professor of pediatrics at the Oregon Health & Science University.

LIVING WITH RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Deb Constien, diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) at age 13, said pain and fatigue have been part of her life for the past 43 years. Fortunately, the era of biologic medications for RA has been a game changer for her and her 26-year-old son, who also has RA, as these medications have stopped the progression of their disease. Nonetheless, living with RA means thinking through and prioritizing daily activities and allocating tasks to others to accommodate the energy-limiting nature of the disease. “You have to think and prioritize every movement you make,” she said.

Constien said she is a volunteer with the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) group, a global, volunteer-driven, not-for-profit organization committed to improving outcomes for patients with autoimmune and musculoskeletal diseases through advancing the design

and quality of clinical studies.1 This group has collaborated with patients to identify three important domains for clinical trials: pain, fatigue, and independence.

One challenge, said Constien, is that each person with RA has a different experience dealing with limitations in physical function and participating in life. RA patients struggle with having control over their lives and with needing assistance, she said, because assistance can be both supportive and independence-limiting. Constien also mentioned how the role of shame associated with having a disability interfered with utilizing necessary support services and accommodations, such as Social Security Disability Insurance. For example, Constien emphasized hesitancy to use elevators as opposed to stairs and reluctance to use a handicap placard due to the associated stigma of being a person with a disability. Finally, she stressed the importance of involving patients in research and gaining their perspectives, since they are the experts in the experience of living with chronic pain.

CURRENT EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT BEST PRACTICES IN MEASURING AND ASSESSING CHRONIC PAIN

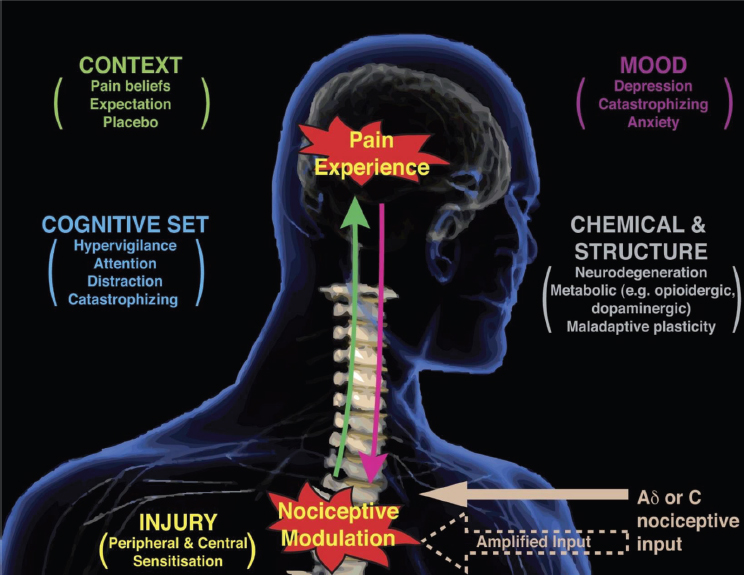

Steven George said there is substantial evidence delinking anatomic pathology from pain severity. As a result, imaging is not recommended for diagnosing non-specific and nociplastic spine-related pain and making treatment decisions. He noted that because evidence linking anatomy with pain is weak, there is limited value in using diagnostic terms such as “discogenic,” “facet joint,” “sacroiliac,” or even “osteoarthritis” for pain assessment. Rather than being driven by anatomy, the pain sensation has several contributors, including modulation by the nervous system; contextual factors such as pain beliefs, expectations, and the placebo effect; cognitive factors including attention, distraction, hypervigilance, and catastrophizing; and mood (Figure 4-1).

George said substantial evidence supports the nervous system’s influence on developing and maintaining chronic pain, suggesting chronic pain is a nervous system disease (George and Bishop, 2018). As a result, there is a great deal of interest in quantifying nervous system processing of nociception using quantitative sensory testing. This type of testing, he explained, is a form of psychophysical testing that assesses somatosensory function by measuring how individuals respond to controlled, standardized stimuli (MacKichan et al., 2008). This move toward assessment of nervous system processing, said George, is consistent with the evidence. However, there is likely limited value in assessing pain related to disability because

___________________

1 Additional information is available at https://omeract.org/ (accessed May 8, 2025).

SOURCES: George presentation, April 17, 2025; Tracey and Mantyh, 2007, used with permission from Elsevier.

such an assessment is good at measuring the response to a painful stimulus but not as good at measuring the pain itself.

Pain-related disability assessment, said George, needs to be more than measuring the ability to feel pain. Rather, it needs to measure the interference or impact pain has on an individual’s life. Pain measurement that considers interference or impact has two key components: the number of days of pain an individual experiences in a set period and how frequently pain interferes with activities. One example of a graded chronic pain scale uses the number of days in the past three months as the primary differentiator, along with responses from the Pain, Enjoyment of Life, and General Activity Scale (Von Korff et al., 2020). These measurements allow standardization, which in turn enables comparison across different populations and conditions. The data from these measurements may have important implications for disability assessment.

George ended his presentation with a caveat: The science supporting the use of physical performance measures, such as Functional Capacity

Evaluations, to determine how much pain is affecting performance, and thus disability or functional levels, is dubious. Evidence does support using self-report measures for assessing pain, and measures that assess pain impact and interference may be relevant for disability determination.

PREVALENCE AND IMPACT OF CHRONIC PAIN IN CHILDHOOD

In 2024, said Anna Wilson, a systematic review of data from 119 studies representing more than 1 million children found that 20 percent of children and adolescents experienced chronic pain lasting three months or longer, with the highest prevalence for headaches and musculoskeletal pain (Chambers et al., 2024). She added that some 5 to 8 percent of children experience moderate to severe functional impairment in activity, engagement, peer relationships, and school attendance resulting from pain, with the prevalence increasing with age and peaking at 14 to 15 years old. Wilson noted that U.S. health care expenditures associated with pediatric pain-related conditions total in the billions, with decade-old estimates ranging from $12 billion (Groenewald et al., 2015) to $20 billion (Groenewald et al., 2014), about double the cost of asthma.

Wilson said sex differences begin around puberty and persist into adulthood, with females reporting more high-impact chronic pain than males. Adults with chronic pain often report onset during childhood, and follow-up assessment of adolescents with chronic pain has shown that pain problems persist into adulthood. The highest rates of persistence occur among children who experience high pain frequency and interference. Moreover, adults with childhood pain onset have higher pain-related disability compared to those with adult onset. She emphasized, however, that just because pain persists across the lifespan does not mean there is no lifespan variability in individual patients over time.

Wilson noted the results of one study that assembled children with chronic pain, their parents, and medical providers to reach consensus about the outcome measures needed for clinical trials of pain interventions in children (Palermo et al., 2021). By unanimous vote, the assembled group recommended that pain severity, pain interference with daily living, overall well-being, and adverse events should be mandatory domains that all trials assess. “Starting with these core domains is a great place not just for clinical trials but for any comprehensive assessment of children’s pain,” said Wilson.

She noted that children’s pain occurs in the context of their parents and family, as well as the broader social and cultural contexts. Thus, assessment needs to consider these factors, as well as how pain interferes with typical development and participation in age-appropriate social roles and activities. Wilson and her colleagues have identified an intergenera-

tional risk for pain, with children with pain being highly likely to have at least one parent with chronic pain (Higgins et al., 2015). In addition, offspring of parents with chronic pain have higher pain levels. Both genetics and shared environments seem to play a role here.

In an ongoing study, Wilson and her collaborators are looking at the effect of maternal chronic pain on children (Stone et al., 2019). What the data have shown so far is that chronic pain affects the physical aspects of parenting, the mother’s involvement in the child’s activities, and the mother’s emotions related to parenting. She noted that childhood is an opportunity to prevent chronic pain in adulthood, as well as to provide patients with coping mechanisms and ways of managing pain that can help them across the lifespan.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SOCIAL SECURITY DISABILITY DETERMINATIONS

Carole Tucker said children as young as eight years old are reliable and consistent reporters of their health conditions using self-report measures such as face pain scales, the pediatric pain questionnaire, Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire, and Pain Catastrophizing Scale for children. However, it is important to take a multidimensional approach to pain assessment because children’s expression of pain differs significantly across developmental stages. This makes standardized assessment challenging for Social Security Administration (SSA) determinations.

Tucker said pain in children has neurophysiological effects on their development, including physically altered movement patterns, psychological anxiety, depression, and strained social and peer relationships. While developing social and peer relationships is a key hallmark of healthy, functioning children, the electronic health record (EHR) does not accurately reflect those relationships. Thus, making a disability determination based primarily on medical diagnoses in the EHR serves children poorly.

Multidisciplinary measurement involves assessing different domains as well as getting those assessments from a variety of professionals, including medical specialists, physical and occupational therapists, psychologists, school personnel, and social workers. Getting important information from the school environment, however, is “a nightmare,” said Tucker, because states regulate who can collect and use school-generated data.

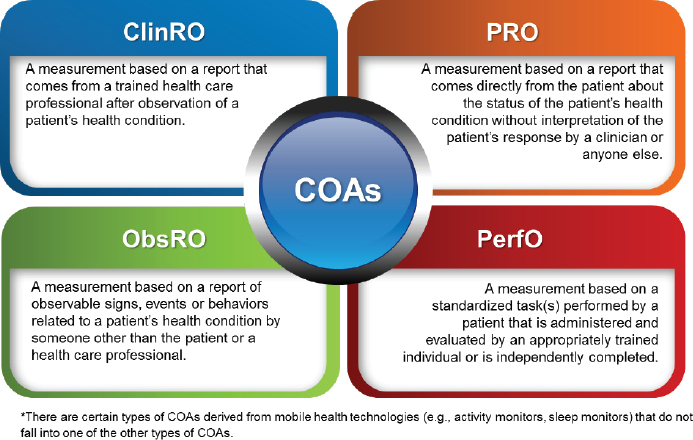

Tucker said several types of clinical outcome assessments could be useful for disability determinations (Figure 4-2). In her opinion, outcome assessments based on patient-reported outcomes should be weighed more heavily than those based on observational reports. At the same time, performance outcomes are helpful because they assess the impact of pain on function and participation.

SOURCE: Tucker presentation, April 17, 2025; FDA, 2018.

If pressed to recommend gold-standard measures for assessing pain in children, Tucker said such measures would need to be developmentally appropriate, account for the child’s developmental stages, and include information from the child, parents, clinician, schools, and others involved with the child. The measures would be multidimensional, assessing pain intensity, location, quality, frequency, duration, and functional impact, and include context-specific measures appropriate for different settings. Finally, they would be longitudinal and include regular assessment over time rather than at a single point. “For Social Security disability determinations, the combination of standardized self-report measures, functional assessment tools, and school and home functioning documentation provide the most comprehensive evidence base,” said Tucker.

After noting challenges with the current SSA framework for pediatric chronic pain, Tucker recommended several improvements SSA could make. These included using enhanced assessment protocols, relying on cross-system collaboration, improving transition planning from childhood to adult, and issuing guidance updates. “Children with chronic pain face unique assessment challenges that impact their access to appropriate disability determinations,” she said. “By improving our measurement tools, documentation systems, and cross-disciplinary collaboration, we can better serve this vulnerable population and ensure appropriate support through the Social Security disability system.”