Risk Management at State DOTs: Building Momentum and Sustaining the Practice (2025)

Chapter: Appendix B: Literature Review

Introduction

Background

Leaders either practice risk management or they routinely practice crisis management.

Risk management is the systematic effort to mitigate uncertainty and variability to an organization’s objectives by addressing both threats and opportunities. When this process is proactively integrated into organizational decision-making, with risks documented and considered, it leads to better management of resources and the creation of a culture of preparedness.

The diversity and complexity of risks facing state DOTs are broad as evidenced by the range of hazards from human-based and natural events. For example, the disruption to transportation system operations due to the COVID-19 pandemic or major hurricanes, like Hurricane Ian, point to a need for risk management to identify response strategies and manage risks to achieve overall strategic objectives. Emerging technologies, economic uncertainty, a changing workforce, and the ongoing requirement to develop and maintain risk-based Transportation Asset Management Plans (TAMPs) also drive the relevance and requirement of adopting formal risk management by state DOTs.

In response, several risk management tools and resources for state DOTs have been developed. However, these are not commonly used, and formal risk management has not been widely adopted. Additional resources are needed to support those working to overcome barriers and initiate, build momentum for, or sustain formal risk management practices.

Research Objective and Task Overview

The objective of NCHRP Project 08-151 is to develop content on how to implement and sustain the use of formal risk management at state DOTS.

This literature review task is the third of five tasks in Phase I of this research effort. Phase I consisted of gathering valuable information, lessons learned, and successful practices from risk management practitioners. Phase II comprised three tasks and dove deeper into the specific content and promotional materials, created content and recommendations, and vetted the content with state DOT practitioners to provide proof of concept.

Literature Review Methodology

The documents reviewed in this memorandum were assembled in two groups: research reports and state or federal guidance documents; and state DOT resources drawn from a web search. Each document was assessed against the project’s areas of emphasis: successes; gaps; value proposition; quantification of risk; organizational change; data and tools; culture of risk; integration of existing processes; and communication and promotion.

To identify documents to review, the research team compiled an initial list of documents where risk management within state DOTs was directly or indirectly discussed. Ten documents were selected from the initial list that seemed the most relevant to thoroughly review. The selected documents largely consisted of other research reports and state or federal guidance documents. Documents were selected based on industry knowledge of key publications; a review of traditional databases such as TRB’s integrated database, Transport Research International Documentation (TRID), and AASHTO’s Transportation Asset Management (TAM) Portal; and an internet search using these keywords: integrating risk into state DOT.

Each document was reviewed and assessed based on the following questions:

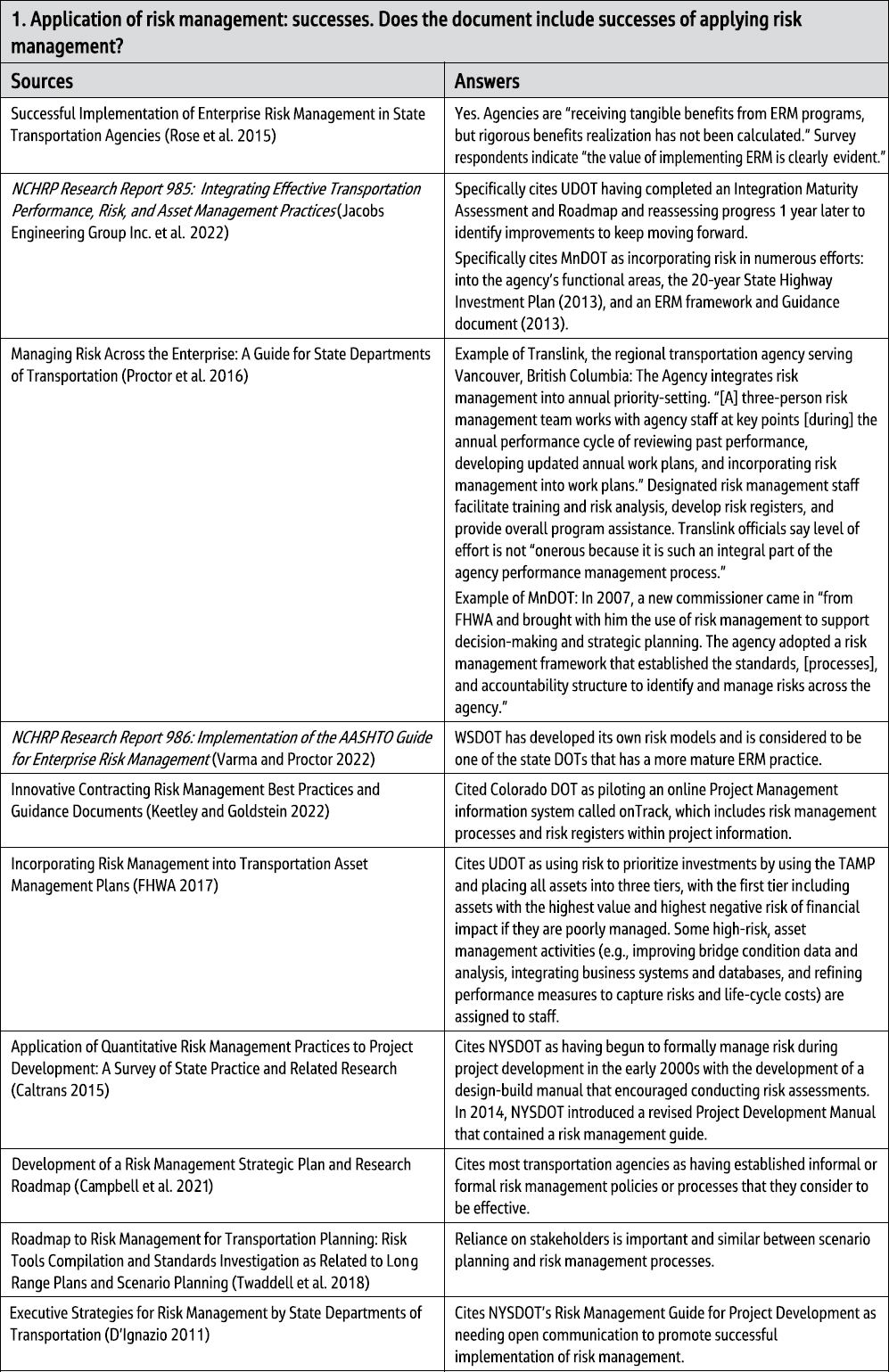

- Application of risk management: successes. Does the document include successes of applying risk management?

- Application of risk management: gaps. Does the document include gaps of applying risk management?

- Area of emphasis: value proposition. How is the value proposition evaluated and shared? What are the key elements that create a value proposition from the top of the organization throughout the agency?

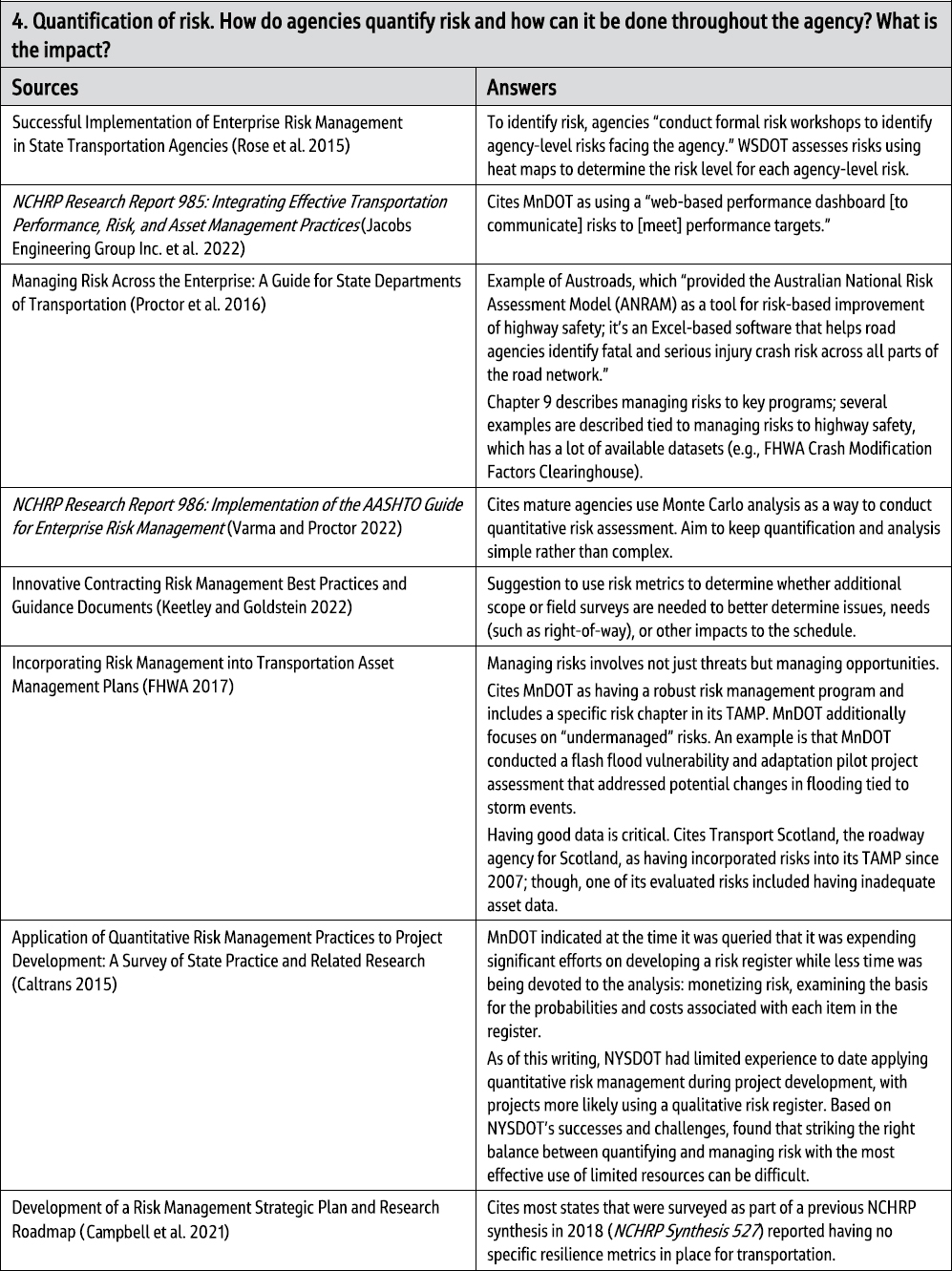

- Area of emphasis: quantification of risk. How do agencies quantify risk and how can this be done throughout the agency? What is the impact?

- Area of emphasis: organizational change. How have agencies successfully managed major change initiatives? Is it top-down or bottom-up? What was done to prepare the agency for change?

- Area of emphasis: data and tools. What are the risk management tools and data agencies use to help in their risk assessments? How can the data be shared across divisional lines—up and down?

- Area of emphasis: culture of risk. What is the tolerance for risk within the agency? How do agencies create a culture that accepts certain failures?

- Area of emphasis: integration with existing processes. What are acceptable methods of considering risk as part of planning, programming, environmental review, asset management, transportation system management and operations, and other existing processes? What concerns do agencies have about ensuring consistency with federal requirements?

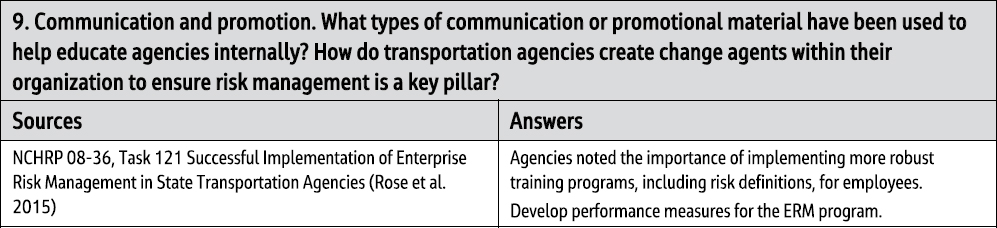

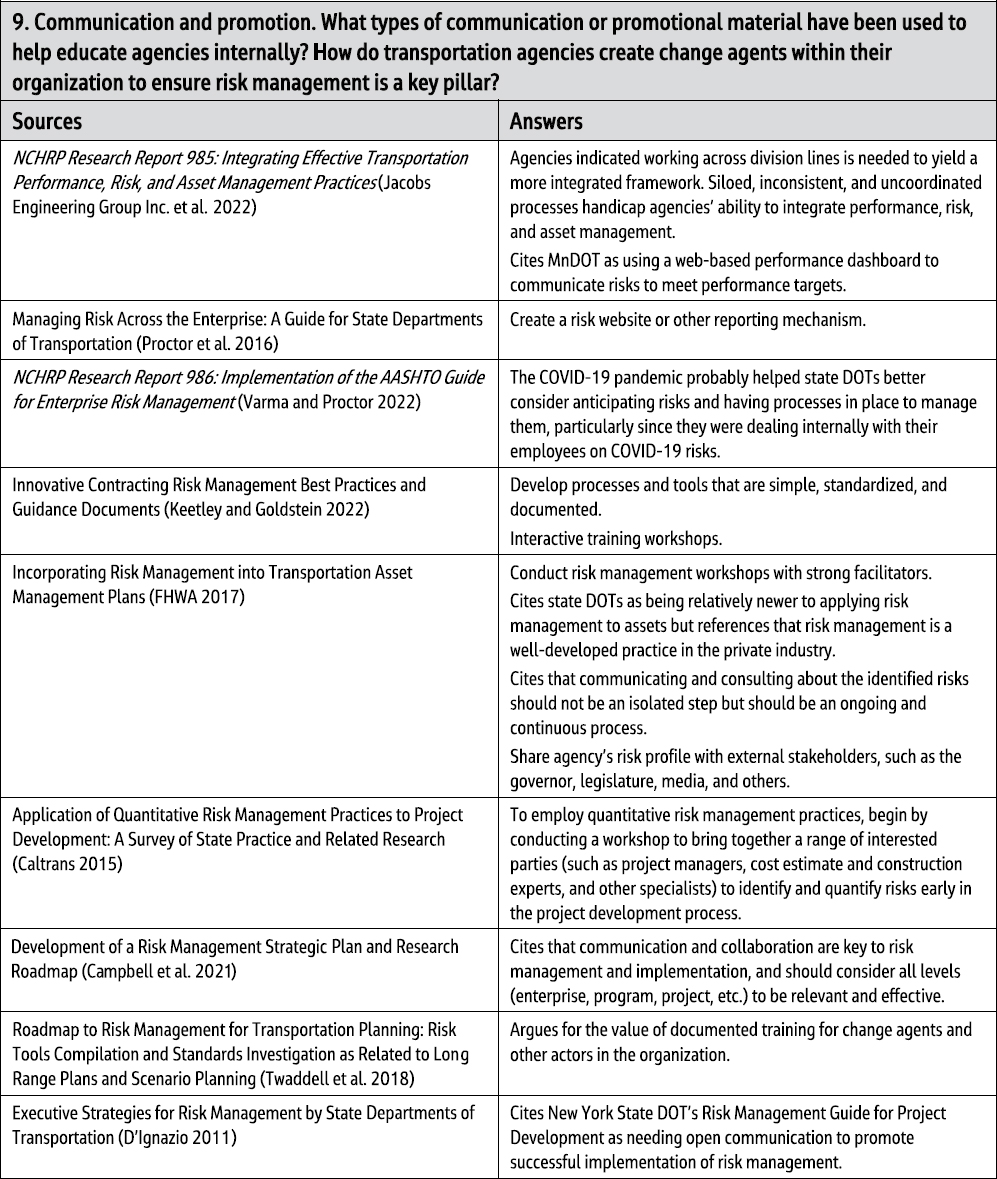

- Area of emphasis: communication and promotion. What types of communication or promotional material have been used to help educate agencies internally? How do transportation agencies create change agents within their organization to ensure risk management is a key pillar?

A secondary internet search was conducted using the keywords “risk management” and “DOT” with the addition of the name of each state. The intent of asking this query was to demonstrate whether state DOTs have readily available risk management resources that are public facing. This basic query yielded slightly over a dozen state DOTs that clearly showed some type of reasonably available risk management resource.

Results of Document Review

List of Documents Reviewed

The 10 documents in this literature review included the following:

- Successful Implementation of Enterprise Risk Management in State Transportation Agencies (Rose et al. 2015)

- NCHRP Research Report 985: Integrating Effective Transportation Performance, Risk, and Asset Management Practices (Jacobs Engineering Group Inc. et al. 2022)

- Managing Risk Across the Enterprise: A Guide for State Departments of Transportation (Proctor et al. 2016)

- NCHRP Research Report 986: Implementation of the AASHTO Guide for Enterprise Risk Management (Varma and Proctor 2022)

- Innovative Contracting Risk Management Best Practices and Guidance Documents (Keetley and Goldstein 2022)

- Incorporating Risk Management into Transportation Asset Management Plans (FHWA 2017)

- Application of Quantitative Risk Management Practices to Project Development: A Survey of State Practice and Related Research (Caltrans 2015)

- Development of a Risk Management Strategic Plan and Research Roadmap (Campbell et al. 2021)

- Roadmap to Risk Management for Transportation Planning: Risk Tools Compilation and Standards Investigation as Related to Long Range Plans and Scenario Planning (Twaddell et al. 2018)

- Executive Strategies for Risk Management by State Departments of Transportation (D’Ignazio 2011)

Summary of Documents Reviewed

Successful Implementation of Enterprise Risk Management in State Transportation Agencies (Rose et al. 2015)

This publication was selected based on the results of a query within AASHTO’s TAM Portal.

This study identifies, analyzes, and describes the qualities of successful implementation of enterprise risk management (ERM) programs in U.S. state DOTs. The study included interviews of DOTs and ERM practitioners to identify state issues associated with ERM implementation and to evaluate the impact these issues have on the quality of its implementation. Out of an initial 44 state DOTs, five agencies were selected for an additional case study on implementation of ERM; this included the following:

- California DOT (Caltrans)

- Massachusetts DOT (MassDOT)

- Missouri DOT (MoDOT)

- Washington State DOT (WSDOT)

- New York State DOT (NYSDOT)

The study found that DOTs are motivated to use ERM practices because they believe these practices will enhance their governance and improve public confidence in the agency and are starting to receive tangible benefits from ERM programs. The research concludes that DOT ERM programs are still in their infancy and agencies realize that mature ERM programs and agencywide risk management cultures take time to develop.

Key findings include the following:

- State DOT ERM programs are in their infancy.

- DOTs are leveraging industry-standard ERM guidelines and frameworks.

- ERM champions are critical for implementation success.

- Designating a stand-alone ERM office is not a requirement.

- Initial evidence demonstrates tangible evidence of ERM benefits.

DOTs recognize the importance of continually improving their ERM programs.

NCHRP Research Report 985: Integrating Effective Transportation Performance, Risk, and Asset Management Practices (Jacobs Engineering Group Inc. et al. 2022)

This publication was selected based on industry knowledge of the report as well as being identified in a query within several industry databases, including AASHTO’s TAM Portal and the National Academy of Engineering.

This report was prepared under NCHRP Project 08-113, “Integrating Effective Transportation Performance, Risk, and Asset Management Practices.” It provides guidance, recommendations, and successful implementation practices for the following:

- Integrating performance, risk, and asset management at transportation agencies.

- Identifying, evaluating, and selecting appropriate management frameworks.

- Recruiting, training, and retaining human capital to support asset management and related functions.

Representative examples of risk management deployment are described in the report. State DOTs referenced in this report as applying risk management include the following:

- Minnesota DOT (MnDOT)

- Vermont Agency of Transportation (VTrans)

- Utah DOT (UDOT)

- Caltrans

The report identifies the following key focus areas as integral to asset management integration efforts:

- Institutional approaches to integration

- Data and software needs

- Personnel and skills

- Policy and agency structure

- Resource requirements

Managing Risk Across the Enterprise: A Guide for State Departments of Transportation (Proctor et al. 2016)

This publication was selected based on industry knowledge of the report as well as being identified during a query within AASHTO’s TAM Portal.

A 27-page quick guide and project overview presentation associated with NCHRP Project 08-93 may be found at https://apps.trb.org/cmsfeed/TRBNetProjectDisplay.asp?ProjectID=3635.

This publication is a guide that summarizes how state transportation agencies can establish and benefit from an ERM program. The guide expands on several previous research efforts.

Of note, this guide

- Includes a chapter that reviews the state of practice and provides examples of risk applied to typical business areas (Chapter 10).

- Provides a get-started roadmap/framework to identify and manage risk.

- Identifies available tools, and develops new tools where appropriate, that agencies might find useful in identifying and managing risk (Chapter 11).

- Reviews several state DOTs and how risk is managed within state DOT asset management.

Key findings of incorporating ERM into state DOTs include the following:

- Provides documented benefits.

- Applies to state transportation agencies.

- Builds credibility and transparency.

- Supports decision-making.

- Complements performance.

- Provides consistency and continuity in services.

- Minimizes threats and capitalizes on opportunities.

NCHRP Research Report 986: Implementation of the AASHTO Guide for Enterprise Risk Management (Varma and Proctor 2022)

This publication was selected based on a query of the National Academy of Engineering database.

NCHRP Research Report 986 documents the activities of state DOTs that implemented the risk management methods developed as part of NCHRP Project 08-93, “Managing Risk Across the Enterprise: A Guidebook for State Departments of Transportation,” which was published six years prior in 2016.

This report is targeted at those in leadership and management positions at state DOTs who are looking to integrate risk management principles and practices in their agencies. This research was initiated in 2018, with pilot activities beginning in mid-2019. The COVID-19 pandemic that became widespread in 2020 influenced this research and results.

The report

- Explains how state DOTs can establish and benefit from an ERM program.

- Describes how to manage risks at four levels: enterprise, program, project, and activity.

- Provides detailed summaries of how risk management is being successfully applied nationally and internationally to transportation program areas.

Three state DOTs—Tennessee, Utah, and Washington State—were pilot agencies that joined seven other states that met regularly to discuss ideas, challenges, solutions, and experiences of incorporating risk management in their agencies. As part of the research effort, the research team held regional meetings to increase awareness of the 2016 guide. Other key activities of the pilot state DOTs included creating risk management tools, forming a risk management community of practice, and other engagement activities, including peer exchanges, webinars, and outreach to other state DOTs. Documents and tools from the pilot state DOTs are included in report appendices.

The report cites the following key risks facing state DOTs:

- Hiring and retaining employees with the skills the DOT needs.

- Improving cultural sensitivity and inclusions and increasing employee diversity.

- Enhancing employee performance and leadership development.

- Managing knowledge.

- Mitigating environmental threats to corridors.

- Reducing variability in quick-clearance efforts.

- Ensuring consistency and quality in construction plans.

- Reducing the risk of late or incomplete construction plans.

Innovative Contracting Risk Management Best Practices and Guidance Documents (Keetley and Goldstein 2022)

This publication was selected based on an internet query of the following words: integrating risk management into state DOTs.

This research documented national transportation industry risk management practices to inform the development and implementation of a comprehensive risk management program for the Michigan DOT Innovative Contracting Unit. Best practices were collected to inform project managers about managing project risk to “improve project delivery on a consistent basis.”

The report contains a literature review and desktop survey of 10 state DOTs, which included the following states: Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Washington.

Representative best practices findings included the following:

- Obtain leadership support to help the program gain acceptance and region buy-in and to promote risk philosophy.

- Develop processes and tools that are simple, standardized, and documented.

- Identify risks of greatest concern and focus the attention on critical items.

- Focus on mitigating schedule risks.

This research also included preparing a set of formal risk management guidance documents, templates, and tools, which included a variety of items, such as a project risk management plan, risk breakdown structure, risk assessment matrix, and risk register. Additionally, an interactive training program on the risk management workbook and associated templates, documents, and tools were created.

Section 2.9 of the report includes recommendations for the risk management development phase within the following key topics: phased approach, scalable process, documentation and tools, project team responsibilities, risk workshops, training, industry and stakeholders, cost estimates and schedules, and leadership support and risk culture.

Incorporating Risk Management into Transportation Asset Management Plans (FHWA 2017)

This publication was selected based on its inclusion as a useful listed resource in NCHRP Research Report 970: Mainstreaming System Resilience Concepts into Transportation Agencies: A Guide (Dorney et al. 2021).

The FHWA issued this publication to provide guidance on the risk element of the TAMP requirement. The publication was issued the year after the FHWA adopted a final TAMP rule that elaborated on the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (2012) (MAP-21) requirement, which amended 23 U.S.C. 119 and required state DOTs to develop risk-based TAMPs. This document “defines risk and provides guidance on how the risk element can be applied to meet risk-based TAMP requirements.”

The document reiterates that risk-based TAMPs “acknowledge, identify, assess, and prioritize risks that could affect performance.” Risk-based TAMPs “also help agencies make difficult tradeoffs of scarce resources to address top-priority risks.”

Key findings include the following:

- Key to risk management success is high-level (top-down) support.

- “A successful, risk-based, asset management program includes trade-off scenarios” that illustrate which trade-offs reduce the greatest risks.

- Integrating processes may lead to greater success, such as reviewing “risks and risk registers with the periodic review of performance.”

Application of Quantitative Risk Management Practices to Project Development: A Survey of State Practice and Related Research (Caltrans 2015)

This publication was selected based on an internet query of the following words: integrating risk management into state DOTs.

This study summarizes an information-gathering effort sponsored by Caltrans that examined both “domestic and international published and in-process research” that addresses “the application of quantitative risk management practices to transportation project development.” The effort to identify the use of quantitative risk management practices applied during project development was conducted (1) using a literature search, and (2) by contacting representatives of state DOTs who indicated their practices were employed by their agencies.

Based on the input from the AASHTO Standing Committee on Planning, the following state DOTs were contacted: Minnesota, Nevada, New York, Utah, Virginia, and Washington. Vermont was noted as also developing quantitative risk management practices for use during project development but indicated they had nothing to share at the time.

Development of a Risk Management Strategic Plan and Research Roadmap (Campbell et al. 2021)

This publication was selected based on industry knowledge of the report.

This research study is part of a broader effort that aims to create planning documentation to help further the integration of risk management into transportation agencies. This final report contains findings of a state-of-the-practice literature review and gap analysis, engagement webinars and events, and stakeholder/agency workshops, which fed into creating the Strategic Approach and Action Plan as well as the research roadmap.

Roadmap to Risk Management for Transportation Planning: Risk Tools Compilation and Standards Investigation as Related to Long Range Plans and Scenario Planning (Twaddell et al. 2018)

This publication was selected based on an internet query of the following words: integrating risk management into state DOTs.

This document provides guidance to help transportation agencies apply risk management methods and techniques to the planning process. The report is not intended to be a how-to manual but instead presents general approaches to identifying and understanding risks associated with transportation decisions.

Executive Strategies for Risk Management by State Departments of Transportation (D’Ignazio 2011)

This publication was selected based on industry knowledge of the report.

The objective of this report was to describe how DOT leadership uses risk management in conducting business and to identify executive strategies that may be useful to leadership for ERM. The document reported that DOT leadership needs to be aware of risk management strategies being implemented at multiple levels, including at the enterprise, program, and project levels.

This report includes a survey of 43 of the 52 DOTs to identify the risk management practices being implemented. Follow-up interviews occurred with the three top DOT agencies that were considered to be advanced in risk management, based on the results of the survey.

This report includes recommendations related to the following key topics:

- Leading the development of policies and communication.

- Supporting the integration of the risk management process through the DOT.

- Appointment of an executive risk manager.

- Participation in national ERM efforts.

Summary of Findings from Documents Reviewed

This section presents findings from the documents reviewed in response to the themed questions.

Summary of Findings: Successes

Summary of Findings: Gaps

Summary of Findings: Value Proposition

Summary of Findings: Quantification of Risk

Summary of Findings: Organizational Change

Summary of Findings: Data and Tools

Summary of Findings: Culture of Risk

Summary of Findings: Integration with Existing Processes

Summary of Findings: Communication and Promotion

Internet Query of State DOT Risk Management Web Pages

As part of the literature review effort, a secondary internet search was conducted to determine whether there were readily available risk management resources associated with state DOTs currently online.

The following results of that search showcase states that had relevant web pages. This does not represent an exhaustive search. All web page snapshots were taken on November 7, 2022, though these images do not show the full extent of the web page image in several instances.

Arizona DOT (ADOT)

ADOT Asset Management web page has specific reference to risk management analysis as it relates to TAMP content.

Colorado DOT (CDOT)

CDOT Risk Management web page is housed with its Program and Project Management web page.

Website: https://www.codot.gov/business/project-management/scoping/risk-management.

Maryland DOT (MDOT)

MDOT Risk Management and Safety web page (MDOT has an Office of Risk Management and Safety).

Website: https://www.mta.maryland.gov/safety-quality-assurance-risk-management.

Minnesota DOT

Minnesota Project Management Risk web page (with links to guidance and tools).

Website: http://www.dot.state.mn.us/pm/risk.html.

Montana DOT

Montana Risk Management web page (with links to guidance and tools).

Website: https://www.mdt.mt.gov/business/consulting/risk-mgmt.aspx.

Nevada DOT

Nevada DOT weblink to Risk Management and Risk-based Cost Estimate Guidelines (2021).

Website: https://www.dot.nv.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/4518/637637657516400000.

New Jersey DOT (NJDOT)

NJDOT Risk Management web page (with links to flow charts, guidance documents, and templates).

Website: https://www.state.nj.us/transportation/capital/pd/process_riskmgt.shtm.

NYSDOT

NYSDOT weblink to Risk Management for Project Development document.

Oregon DOT (ODOT)

ODOT weblink to the Guide to Managing Project Risks for ODOT Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (2019)

Website: https://www.oregon.gov/ODOT/Engineering/Docs_RMVE/Managing-Project-Risks-ODOT-STIP.pdf.

Tennessee DOT (TDOT)

TDOT weblink to Enterprise Risk Management Guide.

Website: https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tdot/documents/InternalAudit/TDOT_Risk_Management_Guide.pdf.

UDOT

UDOT web page housed within project management and project delivery tools web page (with links to risk management tools for qualitative risk and risk model for Monte Carlo analysis).

Website: https://www.udot.utah.gov/connect/business/project-management-project-delivery-tools/.

VDOT

VDOT Risk Management Worksheet web page (with links to worksheet template and guidance document).

WSDOT

WSDOT weblink to Project Risk Management Guide.

Website: https://wsdot.wa.gov/publications/fulltext/CEVP/ProjectRiskManagementGuide.pdf.

Conclusions

Risk Management Implementation Successes and Gaps

The question posed: Did the literature include successes and gaps of applying risk management?

Risk management is being implemented to a certain degree within state DOTs. Literature published in 2021 indicates most transportation agencies have some type of informal or formal risk management policies or processes established that they consider to be effective. This is somewhat consistent with what was reported a decade prior in a 2011 publication; many state DOTs queried at that time claimed to have formal, published risk management policies and procedures (D’Ignazio 2011). In the 2011 report, those queried state DOTs indicated the policies and procedures were applied at varying degrees, with nearly 20% of queried state DOTs indicating they never apply appropriate strategies. It should be noted that during this period between 2011 and 2021, the transportation industry was beginning to move toward enterprise risk management as compared with project-level risk management. So, while the 2011 report provides some context as to the early stages of risk management, the span between the two studies also experienced a growth in the broadening of the application of risk from project-based to enterprise risk management.

When state DOTs formalize enterprise risk management, they often follow a framework with guidance, methodology, policy, and tools to systematically assess risk and adopt strategies and policies to manage it. Having parameters or a policy framework to follow is critical. The creation of policies and guidance and building a framework to follow have helped numerous state DOTs. For MnDOT, a new commissioner came in from FHWA in 2007 and brought with him the use of risk management to support decision-making and strategic planning. The agency established standards, processes, and accountability to identify and manage risks across the agency. Other states have indicated that the lack of clear policy results in inconsistent practices across

the agency. To maintain momentum, state DOTs should reassess progress regularly to identify improvements to help sustain the risk management practice. For instance, UDOT has completed an Integration Maturity Assessment and Roadmap that assesses progress.

Educating state DOTs on the benefits of risk management is important for building the practice. Many state DOTs report they are receiving clear, tangible benefits from ERM programs. However, due to the infancy of implementing risk management, the quantification of realized benefits may often not be calculated. If state DOTs are better educated on the realization of benefits, perhaps there would be greater momentum for state DOTs to build and sustain a practice. A sampling of the benefits reported that could be used to educate state DOTs included better decision-making; maximizing public investment; improved project selection; improved transparency and credibility; and gaining insight into the overall portfolio status and projected performance.

The need for additional staff support is a commonly identified challenge and gap. State DOTs often cite workforce capacity as one of the largest impediments to building and sustaining risk management. In addition to insufficient resources, perceived competing priorities are another aspect cited as being an obstacle to ERM.

Other commonly cited challenges included the following:

- Need for standards and policies regarding collecting and using data, tools, and resources and agency structure, personnel, and skills development. Best management practices for risk management implementation are also needed.

- Access and integration across the state DOT.

- Understanding of the benefits of risk management.

- Adequate data.

- Training.

Organizational Structure

The following questions were posed:

- How have agencies successfully managed major change initiatives? Is it top-down or bottom-up?

- What was done to prepare the agency for change? How is the value proposition evaluated and shared?

- What are the key elements that create a value proposition from the top of the organization throughout the agency?

- What is the tolerance for risk within the agency?

- How do agencies create a culture that accepts certain failures?

One of the greatest takeaways from the literature review is that a risk management champion and executive leadership support are key to building and sustaining momentum. Literature commonly cited implementing ERM with a top-down approach, with senior executive leadership support as extremely important. Part of this may initially require educating and demonstrating to leadership the value of applying risk management. Champions not only have to be identified but also equipped with knowledge of the value of risk management. An example of executive leadership was cited for TDOT, in which its chief engineer conducted the opening remarks at an agency risk management workshop, which helped to emphasize the importance of underlying leadership support and buy-in for risk management. While some state DOTs have designated risk management staff, the literature review did not suggest this was a common practice. In many cases, the responsibilities are usually absorbed into existing staff’s roles.

Establishing or defining risk management within an agency takes time. One document laid out a simple process, with the first step being to base risk management on policy. For instance, the first step is for the agency director, commissioner, or commission to issue a clear policy that the agency

will adopt or ingrain risk management into its strategic planning and performance management processes.

For successful organizational change, it was noted that risk management must be practical to be effective. To prepare agencies and staff, tools need to be created and employees need to be educated to understand risks and to successfully manage them. To create a culture of risk management at all levels, training needs to be conducted agencywide.

Agencies are looking to national and international standards to design their risk management programs. Another report cited that people and organizations are more likely to adopt strategies that are used by their peers; in other words, risk management implementation gains momentum when the knowledge of implementation successes spreads to others within the industry.

Risk Management Application, Integration, and Communication

The following questions were posed:

- What are the risk management tools and data agencies use to help in their risk assessments?

- How can the data be shared across divisional lines—up and down?

- How do agencies quantify risk and how can it be done throughout the agency? What is the impact?

- What are acceptable methods of considering risk as part of planning, programming, environmental review, asset management, transportation system management and operations, and other existing processes?

- What concerns do agencies have about ensuring consistency with federal requirements?

- What types of communication or promotional material have been used to educate agencies internally?

- How do transportation agencies create change agents within their organization to ensure risk management is a key pillar?

Keep it simple. To help with risk assessment, literature often suggests that tools (as well as policies or programs) be simple, scalable, and rightsized. For instance, UDOT uses both qualitative and quantitative tools depending on project size (e.g., whether the project is less or more than $20 million). Literature identified that state DOTs may be applying quantitative risk management to major capacity projects but may not be doing so as frequently or in-depth on smaller-scale projects. The increased frequency in application to major projects could be a result of the quantitative risk management requirements for major projects set forth under the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU), when total project cost exceeds $500 million.

When quantifying risks, documentation often cited the desire to keep it simple and scalable rather than complex. For more complex scenarios, the use of Monte Carlo analysis is one of the most cited tools used to conduct quantitative analysis. The NYSDOT reported that striking the right balance between quantifying and managing risk was the most effective use of limited resources.

Online databases and risk websites for internal agency staff to easily access were also identified as desired tools to use to help in assessing risks. An internal agency website could be used as a reporting mechanism. Specific cited online examples included the following:

- The CDOT is piloting an online Project Management information system called onTrack, which incorporates risk management processes and risk registers within project information.

- The MnDOT is using a web-based performance dashboard to communicate risks to meet performance targets.

- In Australia, Austroads uses an Excel-based software that helps road agencies identify fatal and serious injury crash risks across all parts of the road network.

- State DOTs use FHWA’s Crash Modification Factors Clearinghouse and its datasets to manage risks to highway safety.

The development of a suite or catalog of risk-based tools was noted as being potentially useful; though one report cited concerns with spending more time developing the right tools and templates rather than doing the actual risk analysis, which is the most important aspect.

Literature reviewed indicates risk management is being integrated with numerous existing processes. State DOTs appear to do a good job of integrating risk management into areas where it is required, like incorporation into TAMPs or on major projects as required by FHWA. Due to federal regulatory requirements, with the addition of the risk-based requirements in the Moving Ahead for Progress Act in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) in 2012 and FHWA’s Asset Management Final Rule in 23 CFR Part 515 in 2017, incorporation of risk management into TAMPs is one of the more frequent ways in which state DOTs are implementing the practice. Even with the incorporation of risk into TAMPs, there is a lack of a consistent risk management approach.

Across the literature reviewed, MnDOT was routinely cited as having a robust risk management program. MnDOT includes a dedicated risk chapter in its TAMP. MnDOT also incorporates risk into numerous other efforts, including its functional areas. Nearly a decade ago, MnDOT incorporated risk in its 20-year State Highway Investment Plan and created an ERM framework and guidance document. Another example was the flash flood vulnerability and adaptation pilot project assessment that MnDOT conducted to address potential changes in flooding tied to storm events. UDOT was also noted to use risk to prioritize investments by using the TAMP and placing all assets into three priority tiers.

Translink, the regional transportation agency serving Vancouver, British Columbia, integrates risk management into its annual priority-setting. Translink officials indicate the level of effort is not onerous because it has become an integral part of the agency’s performance management process.

Other applications of risk management include project-level integration, with WSDOT having a strong project management process that includes directives to identify risks. As for the incorporation of risk into the construction bid process, TDOT has prepared a detailed checklist to accompany every complex project when it is submitted for scheduling in the bidding process; this is one way to capture risks to mitigate project delays.

Though not reported as often in the literature reviewed, leveraging partnerships is another method in risk management. For instance, risks managed by state DOTs may be different from those managed by MPOs. MPOs may focus more on planning and programming, whereas state DOTs’ responsibilities focus more on planning, funding, implementing, and operating a project.

Lack of communication, alongside lack of workforce support, was cited as one of the likely largest knowledge gaps regarding risk management. Several documents reported the need for better communication and education for incorporating risk management within agencies. It was noted that staff need terminology defined and formalized policies, processes, tools, and metrics to build a risk management culture. Culture of risk and tolerance begins with a consistent understanding and communication across the agency of the basic principles and terminology of risk management. Also, while only cited once in the reviewed literature, formal memoranda and public communications were listed as ways to communicate risk management issues both internally and with the public.

Bibliography and References

AEM Corporation. (2020). CDOT Risk and Resilience Analysis Procedure. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/54937/dot_54937_DS1.pdf.

Antofie, T. E., Doherty, B., and Marin Ferrer, M. (2018). Mapping of Risk Web-Platforms and Risk Data: Collection of Good Practices. JRC Technical Reports. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, Belgium.

Caltrans. 2015. Application of Quantitative Risk Management Practices to Project Development: A Survey of State Practice and Related Research. California Department of Transportation, Sacramento. https://dot.ca.gov/-/media/dot-media/programs/research-innovation-system-information/documents/preliminary-investigations/application-of-quantitative-risk-management-practices-pi-a11y.pdf.

Cambridge Systematics, Inc. (2011). NCHRP Report 706: Uses of Risk Management and Data Management to Support Target-Setting for Performance-Based Resource Allocation by Transportation Agencies. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/13325/chapter/1.

Campbell, M. K., Ashdown, M., Zissman, J., Pena, M., and Moser, C. (2021). Development of a Risk Management Strategic Plan and Research Roadmap. NCHRP Project 20-123(04). https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/docs/NCHRP20-123(04)_Final_Report_w_Appendices.pdf.

Colorado Department of Transportation. (2020). Risk and Resilience Procedure: A Manual for Calculating Risk to CDOT Assets from Flooding, Rockfall, and Fire Debris Flow. Denver.

D’Ignazio, J. (2011). Executive Strategies for Risk Management by State Departments of Transportation. NCHRP Project 20-24(074). https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/docs/NCHRP20-24(74)_ResearchReport.pdf.

Dorney, C., Flood, M., Grose, T., Hammond, P., Meyer, M., Miller, R., Frazier, E. R., Sr., Western, J. L., Nakanishi, Y. J., Auza, P. M., and Betak, J. (2021). NCHRP Research Report 970: Mainstreaming System Resilience Concepts into Transportation Agencies: A Guide. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.17226/26125.

FHWA. (2017). Incorporating Risk Management into Transportation Asset Management Plans. Washington, DC. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/asset/pubs/incorporating_rm.pdf.

Gad, G. M., Dawoody, H., Shabana, O., Ryan, C., de la Peña, P. M., Caplicki, E., Minchin, E., Planeta, C., and Weber, W. (2022). NCHRP Legal Research Digest 86, Managing Enhanced Risk in the Mega Project Era. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/26713/chapter/1.

Graglia, D. (2023). How Many Survey Responses Do I Need to be Statistically Valid? Find Your Sample Size. https://www.surveymonkey.com/curiosity/how-many-people-do-i-need-to-take-my-survey/.

Herrera, E. K., Flannery, A., and Krimmer, M. (2017). Risk and Resilience Analysis for Highway Assets. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 2604, pp. 1–8.

Indrakanti, S., Kaliski, J., Kiselewski, K., Forbush, D., Huang, C., Campbell, M., Sirianni, M., Pena, M., Moser, C., and Stokes, C. (2023). NCHRP Web-Only Document 385: Business Case and Communications Strategies for State DOT Resilience Efforts. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC.

Jacobs Engineering Group Inc., Cambridge Systematics, and AEM Corporation. (2022). NCHRP Research Report 985: Integrating Effective Transportation Performance, Risk, and Asset Management Practices. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.17226/26326.

Keetley, A. R., and Goldstein, G. A. (2022). Innovative Contracting Risk Management Best Practices and Guidance Documents. Michigan Department of Transportation, Lansing. https://www.michigan.gov/mdot/-/media/Project/Websites/MDOT/Programs/Research-Administration/Final-Reports/SPR-1711-Report.pdf?rev=132c333e74274c9abf6ef9309cc0a3ef&hash=36BF6CC178A5D6A7309CCD32A34C493B.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. (n.d.). Seven Best Practices for Risk Communication (Self-Guided Module). Office for Coastal Management. Retrieved from https://coast.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/training/best-practices-module.html.

Office of International Programs. (2012). Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery. FHWA, U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC. https://international.fhwa.dot.gov/scan/12030/12030.pdf.

Proctor, G., Varma, S., and Roorda, J. (2016). Managing Risk Across the Enterprise: A Guide for State Departments of Transportation. NCHRP Project 08-93. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC.

Rose, D., Molenaar, K. R., Javernick-Will, A., Hallowell, M., Senesi, C., and McGuire, T. (2015). Successful Implementation of Enterprise Risk Management in State Transportation Agencies. NCHRP Project 08-36/Task 121. Prepared for AASHTO. Parsons Brinckerhoff, NY. https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/docs/NCHRP08-36(121)_FR.pdf.

Twaddell, H., Proctor, G., and Varma, S. (2018). Roadmap to Risk Management for Transportation Planning: Risk Tools Compilation and Standards Investigation as Related to Long Range Plans and Scenario Planning. FHWA, Washington, DC. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/84944.

Varma, S., and Proctor, G. (2022). NCHRP Research Report 986: Implementation of the AASHTO Guide for Enterprise Risk Management. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC.

Varma, S., Dickey, C., Pilson, C., Proctor, G., Bhat, C., Vargo, A., and Dix, B. (2023). NCHRP Research Report 1066: Risk Assessment Techniques for Transportation Asset Management: Conduct of Research. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC.

Washington State Department of Transportation. (2022). Project Risk Analysis Model User Guide. Olympia. https://wsdot.wa.gov/publications/fulltext/CEVP/ProjectRiskAnalysisModelUsersGuide.pdf.

Willis, H. H., Tighe, M., Lauland, A., Ecola, L., Shelton, S. R., Smith, M. L., Rivers, J. G., Leuschner, K. J., Marsh, T., and Gerstein, D. M. (2018). Homeland Security National Risk Characterization: Risk Assessment Methodology. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA.

This page intentionally left blank.