Nuclear Terrorism: Assessment of U.S. Strategies to Prevent, Counter, and Respond to Weapons of Mass Destruction (2024)

Chapter: 4 Geopolitical and Other Changes Eroding Long-Standing Nuclear Security Norms and Practices

4

Geopolitical and Other Changes Eroding Long-Standing Nuclear Security Norms and Practices

4.1 BACKGROUND

Since the development of the first atomic weapon and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II, there has been global concern about how to limit the use and spread of nuclear weapons. Throughout the Cold War, while the United States and the former Soviet Union built up massive nuclear arsenals, they also reached agreements to stabilize the numbers of these weapons and reduce the risk of inadvertently crossing the nuclear threshold. The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought with it fear that the Russian government and the newly independent states of Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan would be unable to effectively control the nuclear weapons within their jurisdictions. This led to joint U.S. and Russian programs to protect and repatriate these weapons, and to protect Russian nuclear material stockpiles made vulnerable by the abrupt disappearance of the centralized command-and-control system.

A decade later, the 9/11 terrorist attacks again elevated concerns about the threat of nuclear terrorism by non-state actors. The dissolution of the Soviet Union along with the threat of global terrorism led to the development of a range of U.S. and other cooperative international government-to-government programs, as well as new international frameworks and agreements, to include:

- The Department of Defense (DOD) Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program, which has evolved into Material Management and Minimization in the Department of Energy (DOE), and multiple program efforts managed by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) in the DOD.

- Material Protection, Control, & Accounting (MPC&A), a DOE program that also grew out of CTR and is currently the International Nuclear Security Program (INS).

BOX 4-1

Summary

A unifying theme in this report is the indispensable role that the United States has played and must continue to play in mobilizing and sustaining global efforts to advance nuclear security. Renewed attention to this imperative is especially important given the erosion in recent years of many of the post–Cold War norms that supported international cooperation in addressing the risk of nuclear terrorism. Most prominent among this shift is Russia’s transition from an important partner in enhancing nuclear security to a violator of long-standing nuclear taboos. This includes the Russian threat to use nuclear weapons as a coercive tool in its war on Ukraine, which had chosen to become a non-nuclear state when the Soviet Union dissolved. This undermines nonproliferation efforts by demonstrating the possible usefulness for an aggressor of possessing nuclear weapons and the relative weakness of a state that does not (Committee Meeting, November 29, 2022).a Given this new reality, there must be strong U.S.-led efforts to adapt and expand the international programs that have to date prevented a successful terrorist nuclear attack and have slowed the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

For three decades, the cornerstone of managing the nuclear terrorism threat has been limiting the number of nuclear weapons and the availability of weapons-usable nuclear materials that may potentially fall into the hands of non-state actors. In recent years, global partnerships in support of arms control, nonproliferation, and combating nuclear terrorism have weakened. The Nuclear Security Summit process that mobilized and focused international attention on the need to manage the risk of nuclear weapons-usable materials ended in 2016 (Bunn 2016; Gill 2020). It was followed by a U.S. administration that, although it made statements in support of international institutions to reduce nuclear terrorism threats, espoused doubts about the effectiveness of international obligations and responsibilities (Arms Control Association 2019; Roth 2020). Meanwhile, China, Russia, India, Pakistan, and North Korea continue to expand their nuclear weapons programs, fueling the anxieties of

- The Second Line of Defense, which included the Megaports Initiative and is now Nuclear Smuggling Detection and Deterrence (NSDD) in the DOE.

- The Global Threat Reduction Initiative (GTRI), now the Radiological Security Program in the DOE.

- The Container Security Initiative (CSI) in the DHS.

- The Customs Trade Partnership against Terrorism (C-TPAT) in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

- The Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI).

- International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS).

other countries in Asia and Europe. Iran has begun to enrich uranium to 60% and above in violation of its obligations under the JCPOA, which could stimulate interest in enrichment in other countries in the Middle East (Cordesman 2021; International Atomic Energy Agency 2023; Lerner 2022; Murphy 2023). Fortunately, intergovernmental and international organizations, such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), have expanded their focus on the security of nuclear materials.

Given this dynamic threat environment, there is an urgent need for the United States to reinvigorate efforts to engage heads of state to work together to close any existing or emerging gaps in the international nuclear security system. Additionally, U.S. prevention and protection programs carried out in cooperation with organizations such as the IAEA and Interpol, as well as with like-minded countries, require increased funding and coordination. A more integrated international approach is needed for managing the evolving nuclear terrorism risk.

Highlights

- Destabilizing changes in the political, societal, and technological environment over the last several years require an increased focus on preventing nuclear and radiological terrorism.

- The increasing amount of nuclear and radiological material being produced worldwide could elevate the amount of material at risk if strict security and materials safeguards are not in place.

Without dialogue between the United States and Russia, and a significant change in the current U.S. relationship with China, cooperation on nuclear and terrorism issues among the three largest nuclear states will vanish.

__________________

a Written materials submitted to a study committee by external sources and public meeting recordings are listed in the project’s Public Access File and can be made available to the public upon request. Contact the Public Access Records Office (PARO) at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine for a copy of the list and to obtain copies of the materials. E-mail: paro@nas.edu.

- U.N. Security Council Resolution 1540 (UNSCR 1540).

- Nuclear Forensics International Technical Working Group (ITWG).

- Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

- International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism (ICSANT).

- The Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism (GICNT).

For an NNSA overview of these strategies and U.S. policies, refer to the NNSA strategic plan (National Nuclear Security Administration 2021).

4.2 WEAKENING POLITICAL, SOCIETAL, AND TECHNOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT

FINDING 4-1: Destabilizing changes in the political, societal, and technological environment over the last several years require an increased focus on preventing nuclear terrorism, both by strengthening and expanding government prevention programs and by reinvigorating and extending international cooperation in this area. These adverse changes include: the increasing amount of nuclear and radiological material being produced worldwide (see chapters 6 and 7); the erosion of norms and international collaboration around nuclear threats and nonproliferation (chapter 4); the blurring of the distinction between state and non-state actors (chapter 3); persistent insider threats (chapter 3); and powerful new technologies for sharing information and misinformation, for manufacturing weapons, and for weapon delivery (discussed in the classified annex to this report).

While it is difficult to measure, verify, and validate the individual contribution to nuclear security of each of these programs and agreements listed above, the historical record is clear: to date no terrorist group has detonated a nuclear weapon, an improvised nuclear device (IND), or a radiological dispersal device (RDD). However, the absence of catastrophe or limited knowledge of major security incidents can contribute to complacency, especially when there are many other urgent issues competing for the attention of national leaders as well as budgetary challenges. As the world moves toward the eighth decade of the nuclear era, there are worrisome indications that the nuclear threat, and in particular the threat from non-state actors, is not receiving the active and ongoing attention it once had by political leaders and the general public.

When it comes to the threat posed by non-state actors, the foundations of nuclear security are well established. The greatest impediment to making an IND or RDD has always been the challenge of obtaining a sufficient quantity of nuclear or radiological material. Accordingly, prevention programs have been designed to make such efforts by non-state actors prohibitively difficult. These programs pursue three outcomes: (1) reducing the amount of nuclear and radiological material available; (2) effectively protecting the material that remains; and (3) detecting and intercepting any material that has moved out of regulatory control. Significant achievements by the United States and its international partners have been made in all three of these areas. However, there are new developments that will most likely lead to a significant increase in nuclear material to include the expansion of arsenals by current nuclear weapons states, the likely emergence of new nuclear weapons states, and the renewed global interest in civil nuclear power as a sustainable source of energy.

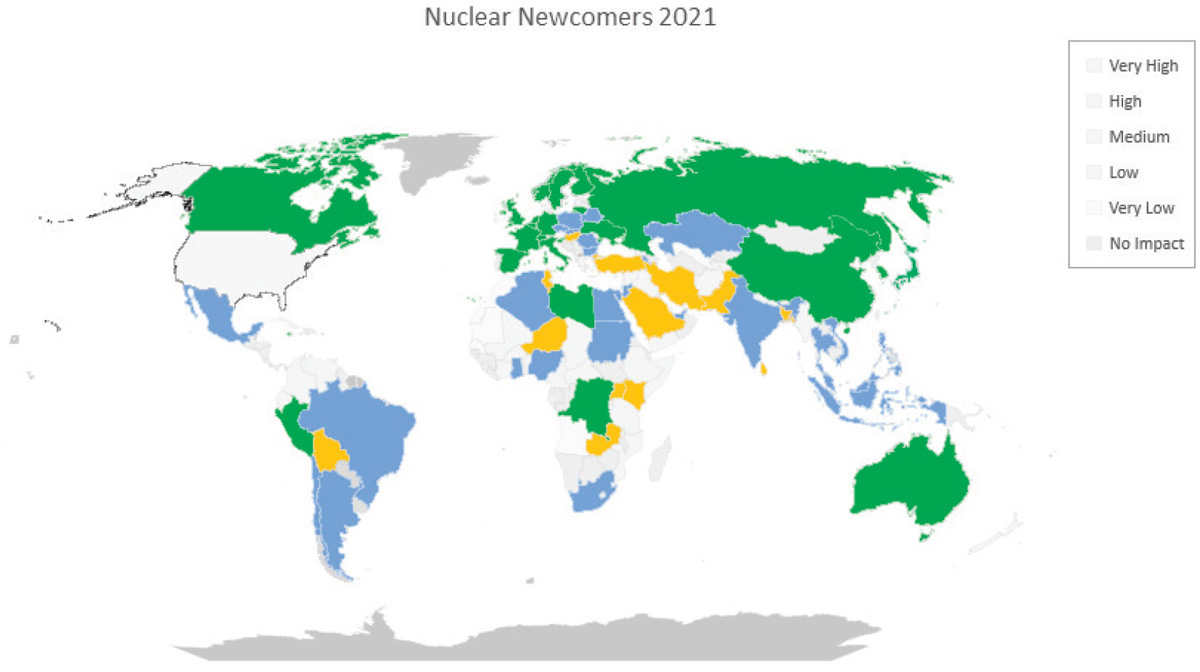

A new chapter in the nuclear era, fraught with risks and challenges but also opportunities, is unfolding. Many countries are embracing the development of new nuclear power programs despite lacking any experience in managing and safeguarding nuclear material and facilities. In the 1990s, Ukraine had returned to Russia the Soviet-era nuclear weapons that had been stationed there, under Soviet operational control. As a consequence of this and long-standing insecurities about reliance on allies, some coun-

tries may think obtaining nuclear weapons is in their interest and others may be reluctant to relinquish any special nuclear material already in their possession. Still others may be motivated to manufacture, or develop the capacity to manufacture, nuclear materials.

The sobering current reality is that the international institutions and partnerships that have been the cornerstone of nonproliferation and counterproliferation efforts are faltering. The disruptive role Russia is currently playing on the world stage is a growing challenge, given that it possesses the world’s largest nuclear arsenal. Additionally, high-level political attention among national leaders has waned since 2016 with the end of the Nuclear Security Summit process initiated by President Barack Obama in 2010. The Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism, jointly led by the United States and Russia, has paused its meetings and working groups. China and North Korea, along with Russia, are expanding their nuclear programs. Pakistan faces challenges to its stability and is locked in an ongoing conflict with India, another nuclear state; Iran continues to produce weapons-usable nuclear materials. Finally, quantities of separated plutonium in the civilian sector are increasing in many countries.

New technologies are also introducing new challenges for nuclear security. While obtaining material continues to be a significant hurdle to developing an IND or RDD, powerful communication tools have made obtaining information about the location of material and how to weaponize it increasingly available, although the accuracy is suspect. New and accessible technologies — such as AI, additive manufacturing, and drones—may simplify the manufacturing and delivery process as well as create new threats and vulnerabilities at nuclear facilities. These trends all point to the need for urgency in bolstering efforts to reduce and protect material, to develop countermeasures for new attack vectors, and to develop a rejuvenated international network of countries working to counter proliferation.

The risks and challenges posed by the expanding and evolving civil nuclear energy sector and those posed by the most dangerous nuclear materials, highly enriched uranium (HEU) and separated plutonium, will be addressed at greater length elsewhere in this report. So too will the issues associated with radiological materials that can be used to fabricate an RDD, given the amount and accessibility of these materials around the world.

4.3 THE ERA OF GREAT POWER COMPETITION AND COUNTERING NUCLEAR TERRORISM

FINDING 4-2: The broken U.S. relationship with Russia, and the increasingly distrustful U.S. relationship with China, have led to a major reduction in cooperation on nuclear and terrorism issues and greater uncertainty about security of the world’s largest nuclear stockpiles.

The once robust collaboration with Russia to secure its nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons-usable fissile materials, and the repatriation of weapons and material from the newly independent states, was the origin for many of the important U.S. government and international programs to prevent nuclear terrorism. These cooperative efforts also

eventually expanded to include work to jointly develop and deploy detection equipment at key Russian land and sea borders with the aim of deterring and intercepting the possible smuggling of uncontrolled nuclear weapons and material. With the post-9/11 focus on preventing terrorists from obtaining nuclear weapons and material, these programs were all expanded to countries outside Russia.

The extensive experience developed through the Russian material protection control and accounting work is currently reflected in the DOE International Nuclear Security Program, which works at both the national and site level with long-term and emerging nuclear states. The post-Soviet removal of nuclear material from the newly independent states by the DOD and DOE expanded into a major worldwide effort by the DOE during the Nuclear Security Summit era. It is now being managed by the DOE/NNSA Office of Material Management and Minimization. Early efforts to secure radiological sources were integrated into a single DOE program that is focused on the consolidation and protection of radiological material both domestically and internationally. Finally, the collaborative work to deploy detection equipment along Russian borders evolved into the DOE Nuclear Smuggling Detection and Deterrence Program, which is providing equipment and working with customs, border police, and investigative agencies along land and sea borders worldwide.

All of these programs would benefit from additional investments, enhanced integration and coordination, and renewed high-level support. Specific recommendations for a subset of these and related programs are outlined in chapter 8.

While these and additional important programs led by other U.S. agencies continue to do excellent work, the collaboration between Russia and the United States, which underpinned many of the global nonproliferation, counterproliferation, and counter-terrorism efforts, is no longer operative since Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine. An additional example of the collapsed cooperative relationship is Russia’s February 2023 announcement that it will suspend participation in New Start (U.S. Department of State 2023), the last remaining strategic arms control treaty with the United States.

The history of U.S. cooperation with China on nuclear- and terrorism-related issues was never as advanced as U.S. cooperation with Russia. More recently, the increasingly intense competition and distrust between the United States and China has resulted in a significantly reduced level of cooperation in all areas, at a time when China is undertaking a significant expansion of its nuclear weapons program.

The March 2023 release of National Security Memorandum 19 (NSM-19) provides an updated U.S. government strategy to “Counter Mass Destruction Terrorism and Advance Nuclear and Radioactive Material Security.” NSM-19 clarifies the overall strategic framework along three mission areas (The White House 2023):

- Counter WMD terrorism: “Combatting all stages of WMD terrorism requires constant vigilance against an ever-changing threat landscape. This NSM also serves as a call to action to disrupt and hold accountable those who provide material, financial, or other support to non-state actors seeking WMD capabilities.”

- Advance nuclear material security: “The peaceful uses of nuclear technology provide considerable economic, medical, and environmental benefits. However, the storage, transportation, processing, and use of highly enriched uranium, separated plutonium, and other weapons-usable nuclear material globally present persistent national security risks to the United States.”

- Advance radioactive material security: “As with nuclear materials and technology, the peaceful uses of radioactive materials provide considerable benefits, although the storage, transportation, processing, and use of radioactive materials globally present a security risk that must be addressed through collective and continuous efforts. Minimizing the use of these materials where technically and economically feasible alternatives exist reduces risk in our collective national security, health, and economic interest.”

RECOMMENDATION 4-1: Based on the Biden Administration’s recently released Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism (NSM-19), the U.S. government, led by the National Security Council, should continue to prioritize and provide oversight of a “whole of government”/“whole of nation”1 focus on preventing nuclear terrorism, to include strengthening and extending ongoing nonproliferation and counterproliferation programs.

Under this strategic direction, agencies such as the DOE, DOD, and the state, with one-of-a-kind programs and unique capabilities, would proactively continue to identify gaps, overlaps, and new opportunities to respond to the changing threat environment. Congress should adequately fund these programs and activities as well as the federal workforce and staff, and provide regular oversight to include conducting hearings.

RECOMMENDATION 4-2: Combating the threat of nuclear terrorism is a shared global interest; the U.S. government should provide strong and visible international leadership as it has done in the past.

Strong U.S. leadership would influence and encourage collaboration among global leaders to prioritize domestic, bilateral, and multilateral nuclear security activities. Such collaboration and cooperation would include capacity-building to prepare for and respond to the changing risk environment. The full range of diplomatic efforts should be brought to bear on the problem and should include engagements with governments that have the resources and technical know-how to contribute to these efforts. Moreover, as appropriate and politically feasible, these efforts should include Russia and China as well as other states with which the United States and its allies have difficult and complicated relations.

___________________

1 In the report, the committee stresses the importance of coordination and capacity-building with state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) governments. The addition of “whole of nation” was added as a reminder that this is not singularly an interagency activity at the federal level but extends to SLTT involvement.

References

Arms Control Association. 2019. “A Critical Evaluation of the Trump Administration’s Nuclear Weapons Policies.” Arms Control Today. https://www.armscontrol.org/events/2019-07/critical-evaluation-trump-administrations-nuclear-weapons-policies.

Bunn, Matthew. 2016. “The Nuclear Security Summit: Wins, Losses, and Draws.” All Nuclear Security Matters. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/37375266.

Cordesman, Anthony H. June 30, 2021. Iran and U.S. Strategy: Looking beyond the JCPOA. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep33760.

Gill, Amandeep S. 2020. Nuclear Security Summits A History. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

International Atomic Energy Agency. 2023. “Verification and Monitoring in the Islamic Republic of Iran in Light of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231 (2015).” GOV/2023/24. https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/23/06/gov2023-24.pdf.

Lerner, K. Lee. 2022. “Policymakers Must Now Assume That Iran Has the Enriched Uranium It Needs to Build a Nuclear Weapon.” Taking Bearings. Harvard Blogs (June 1). https://blogs.harvard.edu/kleelerner/iran-now-has-the-enriched-uranium-it-needs-to-build-a-nuclear-weapon/.

Murphy, Francois. 2023. “Iran Expands Stock of Near-Weapons Grade Uranium, IAEA Reports No Progress.” Reuters, September 4, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iaea-reports-no-progress-iran-uranium-stock-enriched-60-grows-2023-09-04/.

National Nuclear Security Administration. 2021. “Prevent, Counter, and Respond—A Strategic Plan to Reduce Global Nuclear Threats (NPCR).” https://www.energy.gov/nnsa/articles/prevent-counter-and-respond-strategic-plan-reduce-global-nuclear-threats-npcr.

Roth, Nickolas. 2020. “Preventing Nuclear Terrorism.” The Trump Administration after Three Years: Blundering toward Nuclear Chaos, edited by Jan Wolfsthal. American Nuclear Policy Initiative. https://www.globalzero.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Blundering-Toward-Nuclear-Chaos-ANPI-Report-May-2020.pdf.

The White House. 2023. “Fact Sheet: President Biden Signs National Security Memorandum to Counter Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism and Advance Nuclear and Radioactive Material Security”. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/02/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-national-security-memorandum-to-counter-weapons-of-mass-destruction-terrorism-and-advance-nuclear-and-radioactive-material-security/

U.S. Department of State. 2017. Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism.

—. 2023. Russian Noncompliance with and Invalid Suspension of the New START Treaty.

This page intentionally left blank.

SOURCE: Holt 2021.