Evaluation of Manhattan Project Records for Veteran Health and Exposure Assessments (2025)

Chapter: 5 Manhattan Project Exposures and Associated Records

5

Manhattan Project Exposures and Associated Records

This chapter addresses the third subtask in the committee’s charge (see Box 1-1) to characterize the information contained in and the quality and completeness of records related to the types of exposures experienced by military veterans from Manhattan Project activities, including radiological, chemical, and combined exposures. The chapter offers insight into the types of exposure assessment that may be possible based on records identified during the committee’s information-gathering sessions.

The first section of this chapter provides definitions and an overview of what exposure is and its relationship to dose, from which the remainder of the chapter builds. The committee presents its own tiered system to consider various types of exposure and dose assessments. With that tiered framework in mind, the chapter shifts to a brief history of the evolution of the Manhattan Project dosimetry program to provide context for the types of exposure records that are available for 1942–1947. A section with examples of the types of Manhattan Project exposures, both radiological and chemical, follows. The committee then presents a summary of the databases and resources containing exposure information. A synopsis of the likely sources, availability, and state of information on exposures and wastes ends the chapter.

The sites in the statement of task include those related to mining, processing, production, and waste storage (see Figure 3-2 in Chapter 3). Military personnel at each of these sites had different jobs and duties, which may have led to different exposures, including multiple types of radioactive, chemical, and combined forms of waste. The committee requested information about the existence and examples of chemical exposure and dosimetry records at

the three primary sites (Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos), and sought information on the jobs of military personnel from historians and historical documents, all of which could inform potential exposures. It also examined agency databases to supplement information on known exposures. Given that the Manhattan Project compartmentalized its activities, work performed at each site was specialized to specific materials handling, so that people at one site may have had different exposures than those at another site. With the exception of the military police, military personnel at those sites were mostly working side by side with their civilian counterparts (Seidel, 1993). Some military personnel may even have worked at more than one site, adding another layer of complexity to understanding their exposures.

The many definitions of what constitutes waste vary based on context, location, and period, as described in Chapter 2. However, the term waste was defined by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in its official charge to the committee as “anything that is not the intended by-product of an activity or process and that was required to be put in a specific location or managed by the site or group that produced it” (Hastings, 2024). Waste generally implies something unwanted, but not all veterans’ exposures are associated with waste and may include those experienced during industrial and scientific processes. Thus, this chapter discusses exposure more broadly than that specifically from waste products.

OVERVIEW OF EXPOSURE AND DOSE ASSESSMENT

A robust understanding of exposure and dose is necessary for developing and appropriately assessing exposure– or dose–response relationships and evaluating potential health outcomes (see Chapter 6). Thus, the committee considered what information is available related to the type and extent of worker exposures, specifically for military members, during 1942–1947 by site location. This report is not intended to be a textbook reference for exposures or wastes related to Manhattan Project activities. Rather, it gives an overview of the possible types of exposures and their use in exploring the relationships to health outcomes for active-duty military personnel during the Manhattan Project.

Exposure typically refers to the contact between a substance and the human body (NRC, 2012). The definition of dose depends on the context; radiation dose is related to energy transfer or energy absorption, whereas the relevant property for most chemical substances is mass (Cantril and Parker, 1945; EPA, 2019; ICRP, 2007). An exposure to radiation becomes a “dose” when radiation deposits energy in the body; for chemicals, an exposure is typically considered a “dose” when the chemical crosses the external surface of the body (EPA, 2019). Exposure and dose assessments for specific substances involve identifying the individual or population of

interest and quantifying their exposure and dose, through evaluation of exposure-related measurements, modeling, or, most commonly, a combination of these, along with the route, duration, and frequency of exposure (EPA, 2011; Fjeld et al., 2023; Rocco et al., 2008). Such assessments can be complex, as exposures may involve a single substance or a mixture, occur once or often, and be further influenced by time, place, and activity. The human body may be internally exposed to chemical or radioactive substances through inhalation, such as breathing in acid vapors or gaseous iodine-131 (a common by-product of weapons manufacturing); ingestion, such as eating contaminated food or water; dermal contact (absorption); or wounds (e.g., injections such as finger pricks). How a substance enters the body often influences its behavior in the body and potential effects on health or body systems.

Some forms of ionizing radiation, such as gamma radiation, can penetrate the body without physical contact with the source of radiation, resulting in external exposures. Other forms of radiation are easily shielded and present more of an internal hazard. For example, alpha particles (such as that emitted by plutonium-239) can generally be blocked, including by skin, so are typically only a health concern if taken into the body. Of note is that many radionuclides have decay chains that involve multiple types of radiation emissions, making the exposure scenario more complex.

Measuring an individual’s occupational external exposures is easier than internal chemical or radiological exposures. Long-lived radionuclides (e.g., half-lives on the order of millennia—such as uranium-235 and plutonium-239) can potentially have greater chemical toxicity (as heavy metals) than radiological toxicity when taken into the body because radiation is emitted (and deposited in the body) at a slow rate (Kathren and Burklin, 2008; UNSCEAR, 2016). Also, some exposure–response associations have a threshold at or above which an effect is observed, whereas others do not. Understanding these qualities of a substance helps researchers perform exposure assessments; however, the availability of exposure data for individuals or groups remains a crucial factor.

The level of uncertainty in an exposure assessment, along with the ability to draw strong conclusions about exposure–health relationships, strongly depends on data availability. However, even with limited data availability, valuable information can be gained to inform policy decisions and guide further research. Carefully considering the strengths and weaknesses of the data is essential when interpreting results and making recommendations based on the exposure assessment.

Dose reconstruction is a retrospective assessment that can be used to estimate doses to specific or representative individuals (NRC, 1995). Elements and technical aspects of radiation dose reconstruction are discussed in detail elsewhere (NCRP, 2018; NRC, 1995), but key information

includes the specific objective of the study, worker activities and locations, monitoring data, and modeling data.

Personal monitoring data is ideal for individual dose reconstructions. A radiation dosimeter (a device used to measure radiation dose, typically to monitor an individual or workspace) worn by a worker can provide information on their external exposure (within its design and calibration parameters), although care needs to be taken when reconstructing dose from historic dosimetry records, as standards, procedures, and dosimeters themselves have evolved (see section on Evolution of Manhattan Project Dosimetry Program). Estimating internal exposure is more complex because, unlike external exposures, internal dose is not directly measurable. However, methods such as bioassays (e.g., urinalysis or fecal samples) were taken during the Manhattan Project, and can provide information on radioactivity in the body (Brackett and Ushino, n.d.). Computational models can then estimate intake and dose; this is more reliable and precise than using air monitoring data. Bioassays were not systematically conducted during all years of the Manhattan Project, but measurements taken several years after exposure, depending on the biological half-life of the radionuclide, could still provide information on the dose received by an individual worker.

Area monitoring data, which could include air monitoring and surface contamination surveys, can often be used to estimate dose if individual data are not available or practical to obtain and to validate or refine exposure models and provide context for interpreting personal monitoring data. When neither personal nor workplace (i.e., area) measurements are sufficient, process knowledge complemented with computational methods can be used to estimate dose.

Dosimetric uncertainty plays a crucial role that any researcher undertaking a study performing dose reconstruction should consider. For both external and internal dose reconstruction, uncertainties span two broad categories: data issues (including changes in site operations and exposure characterization) and dosimetry issues (covering sensitivity of monitoring methods, exposure geometries, and bioassay uncertainties). Appropriate statistical methods must be applied to account for these uncertainties when estimating radiation dose and failure to properly account for uncertainties in dose estimation can lead to biased results and incorrect confidence bounds for risk parameters. This report will not cover analysis in detail, but there are existing resources that may benefit researchers interested in the science of historic dose reconstruction (e.g., NCRP, 2024; Toohey, 2008).

TIERS OF EXPOSURE AND DOSE ASSESSMENT

The quality and quantity of exposure or dose data determine the depth, accuracy, and type of study that can be conducted. Approaches to exposure assessment can be conceptualized as tiered, with each tier representing a different level of data availability and detail. Illustrative tiers are summarized in Table 5-1 and then described. The tiers do not represent an established classification system but were intended to assist the committee in framing and organizing its feasibility assessment. The appropriate exposure assessment tier will depend on the study situation and objective. For example, a tier 3 study may be the most appropriate to inform a risk management decision or evaluate if a tier 2 or tier 1 study is justified, given limited resources (Jayjock et al., 2007; NCRP, 2018, 2024; NRC, 1995).

TABLE 5-1 Summary of the Committee’s Tiers of Exposure and Dose Assessments

| Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Assign an estimate of exposure to each individual in a study population based on individual exposure measurements. | Assign an estimate of exposure to each individual in a study population based on group-level exposure estimates. | Assign an estimate of exposure to a study population based on group-level exposures estimates through a risk assessment. |

| Data required | Individual exposure measurements Defined cohort |

A) Exposure estimates for groups (e.g., each job and location) based on area monitoring or models Individuals’ employment and job histories Defined cohort |

Exposure estimates for a group (facility average) or groups (e.g., job and location) from area monitoring data or models No defined cohort |

| B) Estimates of group-level exposure limited and primarily based on duration of exposure as a surrogate No direct exposure information |

Tier 1: Individual Estimates Based on Individual Exposure Measures

This tier represents the ideal scenario for conducting an epidemiologic study, where individual-level exposure measurements for each person and time period are available or can be estimated for an identified cohort of sufficient size to discern statistically significant patterns (see Chapter 2). Tier 1 exposure assessment provides the strongest foundation for establishing causal relationships between exposures and health outcomes. Individual-level exposure data allow for the most robust analysis of that relationship. With individual-level data, researchers can account for personal variations in exposure, calculate individual doses, and potentially identify subtle dose–response relationships. However, even in this ideal scenario, challenges may arise, such as missing data for some individuals, certain sites, or specific time periods. Data gaps require careful consideration and may necessitate the use of advanced statistical techniques to appropriately account for missing data. In addition, high-quality information is required regarding an individual’s exposures before and after the Manhattan Project period. The existence of a well-defined cohort assumes that accurate knowledge of health outcomes of individuals is available along with information on relevant covariates, confounders, and effect modifiers.

Tier 2: Individual Estimates Based on Group-Level Exposure

The committee divided this tier into two subtiers based on the amount of information available to perform the exposure assessment. Tier 2A estimates each person’s exposure based on group-level average exposure estimates, typically with groups defined based on job title or location. This scenario is common in occupational and environmental epidemiology studies in which individual exposure measurements may not be feasible or available but those at a group or area level are available. To conduct an assessment at this tier, three key elements are required:

- Detailed job or location histories for each individual in the cohort, such as the time spent in each job and location/area;

- Exposure data associated with each job and/or location over time (if such data are unavailable, then knowledge of the workplace (size of the room, airflow rates and patterns, contamination generation rates, and task/job descriptions) should be available to facilitate mathematical modeling to estimate these exposures), and

- All the job titles or location histories for each individual in the cohort.

With these elements, it becomes possible to assign exposures to individuals for each time period based on job title–level or location-level data. This approach allows for changes in exposure over time and between different roles within an organization; it has been used in some studies of U.S. military veterans. However, this tier assumes a certain level of homogeneity in exposure within a job title, which may not always reflect reality. Variations within the same job title may not be captured, leading to some degree of exposure misclassification.

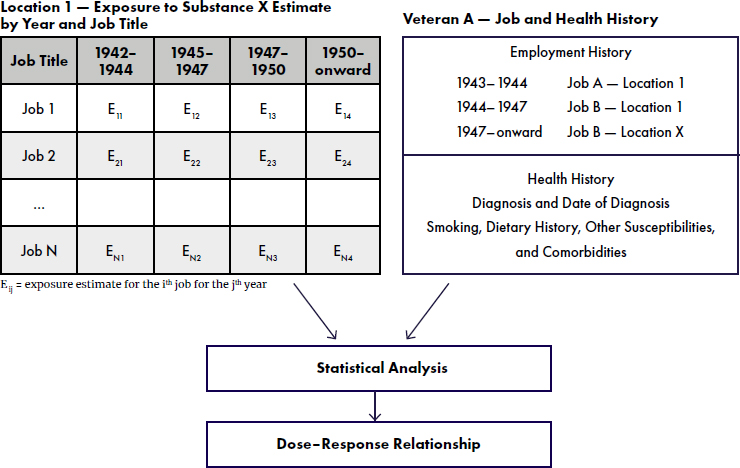

One tool used for a tier 2 approach in occupational epidemiology is a job-exposure matrix (JEM), which is used to systematically assess and quantify exposure to various workplace hazards across different jobs and industries. A JEM links information about job titles with exposure estimates (obtained using monitoring or modeling), allowing researchers to estimate the levels and types of exposures that specific occupations might encounter. A JEM can be used to estimate radiological, chemical, and combined exposures. Since the goal of retrospective exposure assessment is to develop estimates of dose for use in epidemiologic studies, estimating exposure histories (i.e., exposure as a function of time) of various job categories is critical. These job exposure histories are combined with worker employment histories to obtain individual exposure histories. The job-exposure data matrix in the top left of Figure 5-1 is a simple way of organizing exposure estimates to describe, analyze, estimate, and link exposure estimates to workers explicitly (Seixas and Checkoway, 1995). It is simple and has only two dimensions, job title and time. However, a JEM can have many dimensions, such as site, facility, type of process or machine, and availability of exposure controls. When exposures to multiple chemicals need to be accounted for, a separate dimension for each one might be included. Other information, such as production and ventilation records and subjective judgments of exposures made by plant occupational hygienists, can also be separate dimensions. Ideally, highly specific dimensions with all information included would exist, so that the exposure estimates are as precise and free of bias as possible.

JEMs are particularly useful in retrospective studies where direct exposure measurements are unavailable. They help reconstruct past exposures based on job or location/neighborhood histories and known hazard information. They are efficient for large-scale epidemiologic studies where detailed individual exposure assessments (i.e., tier 1) are impractical, such as when reconstructing historic exposures to a large number of chemicals. JEMs are versatile and can be adapted for various study designs, including case-control and cohort. However, their effectiveness depends on the quality and completeness of the data on job histories and exposure levels and ensuring that exposure estimates remain valid for the period of interest (Descatha et al., 2022).

NOTES: The matrix combines information regarding the worker’s job type by year and location. This can be correlated with what is known about the historical use of known substances used in specific job at a specific site and available exposure information (e.g., chemical concentrations, radiation dosimetry records, or bioassay data).

Tier 2B is applicable for when information about variation in exposure concentrations between groups in an occupational study setting is lacking but information on the length of time individuals spent in each job position is available. One approach is to assume that exposure levels are uniform across groups in a JEM and simply assign these based on the duration of time spent in each job. This approach assumes a linear relationship between time spent in a job and the level of exposure, which may not always be accurate. It does not account for potential variations in exposure intensity between different time periods or locations within the same job title. Despite these limitations, this approach can still provide valuable information, especially when more detailed exposure data are not available, but job histories are well documented. If job histories are available, then both radiological and chemical exposure and dose assessments are feasible.

Tier 3: Risk Assessment Based on Group-Level Exposure Data

This tier describes a scenario where exposure measurements or information for mathematical modeling are available for all relevant job titles and locations in a defined area, but no cohort is identified for an epidemiologic study. The focus shifts from epidemiology to risk assessment using the exposure information, combined with dose–response relationships obtained from peer-reviewed literature. This approach allows for estimating potential health risks associated with the measured exposures but cannot directly link these exposures to health outcomes in a specific population. Relying on external data for dose–response relationships introduces an element of uncertainty, as these relationships may not perfectly apply to the exposure scenario. Nevertheless, this tier can provide valuable insights for risk management decisions, particularly when assembling a cohort for an epidemiologic study is not feasible.

Sometimes, exposure measurements or estimates from models are available for only specific locations. Researchers might conduct a partial risk assessment, focusing only on these locations, or estimate exposure scores for jobs or locations with missing values (e.g., based on the overall facility mean). To provide a more comprehensive assessment, researchers may need to use extrapolation techniques or develop models to estimate exposures at unmeasured locations. However, such estimations introduce additional uncertainties into the assessment. This tier of exposure assessment can highlight areas where additional data collection or more sophisticated modeling approaches may be necessary to fully understand the exposure scenario and associated risks.

EVOLUTION OF THE MANHATTAN PROJECT DOSIMETRY PROGRAM

During the Manhattan Project, processes and technology for worker safety were developed and implemented concurrently with the research and manufacture of a nuclear weapon. However, the varying degrees to which worker exposures were monitored and recorded creates a unique challenge for 21st-century researchers who wish to assess the chemical, radiological, and combined exposures of that period. Manhattan Project contemporaries were less concerned about exposure to chemical hazards than to radiological ones, as they understood the basic principles of radiation detection and that it was a known health hazard (Parker, 1947). Present-day investigators need to know the radiation standards in use during the Manhattan Project to work with historical exposure data appropriately.

History of Dosimeter Development

The Manhattan Project’s Health Division was established in 1942 and led by experts from the Metallurgical Laboratory of the University of Chicago and the University of Rochester. Within the division, the Health Physics Section was responsible for improving instrumentation, including dosimeters, to measure radiation levels in the workplace and monitor workers for both external and internal exposure of the different radiation types. A dosimeter is a device used to measure radiation dose, typically in the context of monitoring an individual or a space an individual works. This effort included standardizing units for exposures recorded by the dosimeters. While these groups were the lead for the Manhattan Project on developing these practices, all the sites had their own health physics groups. Despite implementing safety controls, such as specialized protective equipment, controlled access to radioactive areas, and monitoring techniques, the division struggled to maintain comprehensive individual exposure records due to limited resources, time constraints, and the complex nature of varying radiation risks across different project sites (Hacker, 1987).

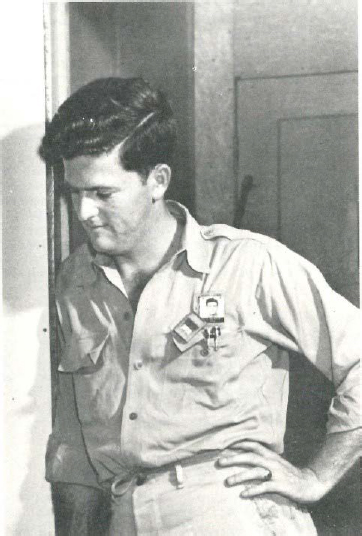

Despite differences in site-by-site rollout of the Health Division’s radiation safety protocols, some common practices were adopted when a site first became operational. During the early months of the Manhattan Project (1942–1943), the most common form of records would likely be surface contamination on various media (mostly wood and metal work surfaces) and air contamination. In addition, direct radiation (exposure measured in roentgens) readings of the work environment were taken and could provide high level information on potential exposure to workers (Taulbee, 2024). The first external radiation dosimeter to be implemented was the pocket ionization chamber (PIC), because the technology existed when the Manhattan Project began and it was easy to wear (see Figure 5-2). However, it could only detect radiation from gamma, X-ray, and beta sources, missing potential dose from neutron sources. These dosimeters also cannot provide information on internal dose, such as that received from inhalation of an alpha-emitting radionuclide. Manhattan Project work required a more robust method to measure each worker’s radiation exposure given the variety of radiation types involved (Advisory Board on Radiation and Worker Health, 2009).

The common practice for external radiation monitoring at most Manhattan Project sites pre-1944 was to issue duplicate PICs to employees anticipated to be exposed (i.e., two PICs to each worker as shown in Figure 5-2) and record exposures daily (Parker, 1947).1 However, PIC

___________________

1 This practice is site and job dependent. During the early years of the Manhattan Project, it is unlikely that administrative staff (likely including many members of the Women’s Army Corps) or military police would have worn dosimeters.

NOTES: Notice the two PICs next to a film dosimeter badge in the upper left pocket underneath the identification. A dosimeter’s location influences its response. (Photograph ca. late 1940s–1950s; original caption reads: “Early film badge and pocket ionization chambers used at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.”)

SOURCE: Auxier, 1980. Used with permission from Elsevier. Copyright © 2025 International Atomic Energy Agency. All rights reserved.

accuracy and reliability depended on ambient and physical conditions (i.e., humidity or physical impact), which often resulted in overestimates of exposure (Watson, 1957). Because of “false-positive” dose readings from routine handling and environmental effects, the lower of the two readings for each day was used to calculate a daily dose for comparison with the daily dose limits at that time. By 1944, the Health Division had developed and implemented a two-element film dosimeter (Pardue et al., 1944) that expanded the detectable types of radiation to neutrons. Thereafter, it was common to record readings from both types of dosimeters to account for their limitations, such as overresponse of a PIC if it was accidentally bumped or jostled. In some cases, workers’ hands were monitored “by micro-ionization chambers or by small film packs contained in special rings” (Parker, 1947). Personnel were also monitored for contamination (e.g., hands and feet), although typically this was for decontamination and not necessarily to

determine or evaluate dose. A 1990 report, Description and Evaluation of the Hanford Personnel Dosimeter Program From 1944 Through 1989 provides a comprehensive review of the Hanford external dosimetry program, including descriptions and technical details of the dosimeters and their calibration, quality control studies, and intercomparison studies (Wilson et al., 1990).

Despite a concerted effort to monitor each worker, not all workers may have received a dosimeter. The health physics divisions at sites were often understaffed and could not always keep up with routine monitoring of individual radiation exposures, leading to gaps in worker records (Lewis, 2024). Notably, radiation exposure monitoring at Oak Ridge began in 1943, and by 1948, over 98% of workers were monitored, but it was not standard procedure for employees to have a radiation dosimeter until November 1951 (Richardson and Wing, 1999). Additionally, the dosimetry program was segregated by sex, and woman were often not given dosimeters. Lack of individual dosimeter records limits the ability to do a tier 1 exposure assessment (GAO, 1985).

While external dosimetry was being refined, determining internal exposure if someone inhaled or ingested a radioactive substance continued to be complicated. In 1945, the Health Division began implementing bioassay urinalysis tests, beginning in Oak Ridge and Los Alamos and later (1946 onward) at other sites for workers who might have taken up plutonium. Routine monitoring for intake of radionuclides was not implemented until after the Manhattan Project ended. The exact dates for standardized exposure monitoring varied from site to site based on the main radionuclides being handled, with plutonium and uranium being of primary concern at most sites. Other radionuclides were later included for monitoring of intake (Brackett and Ushino, n.d.). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has relied heavily on exposure models using air sample data to reconstruct internal doses for workers 1943–1947 (Taulbee, 2024).

Examples of Historic Radiological Exposure Records

During the committee’s information-gathering sessions, multiple presenters provided a variety of examples of dosimetry records from the Manhattan Project, specifically from the three primary sites of Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos. Dosimetry records were requested to understand radiation exposure levels for individuals and in aggregate. The committee also sought information on the jobs of military personnel through historians and historical documents, which could inform potential exposures. The committee heard presentations from several health physicists at NIOSH, Oak Ridge, Hanford, Los Alamos, and the Army Corps of Engineers, several of whom had experience working with historic dosimetry records. Requests

for dosimetry records and information were also made to VA, U.S. Army Center for Dosimetry, and Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Legacy Management, but no information was provided to the committee.

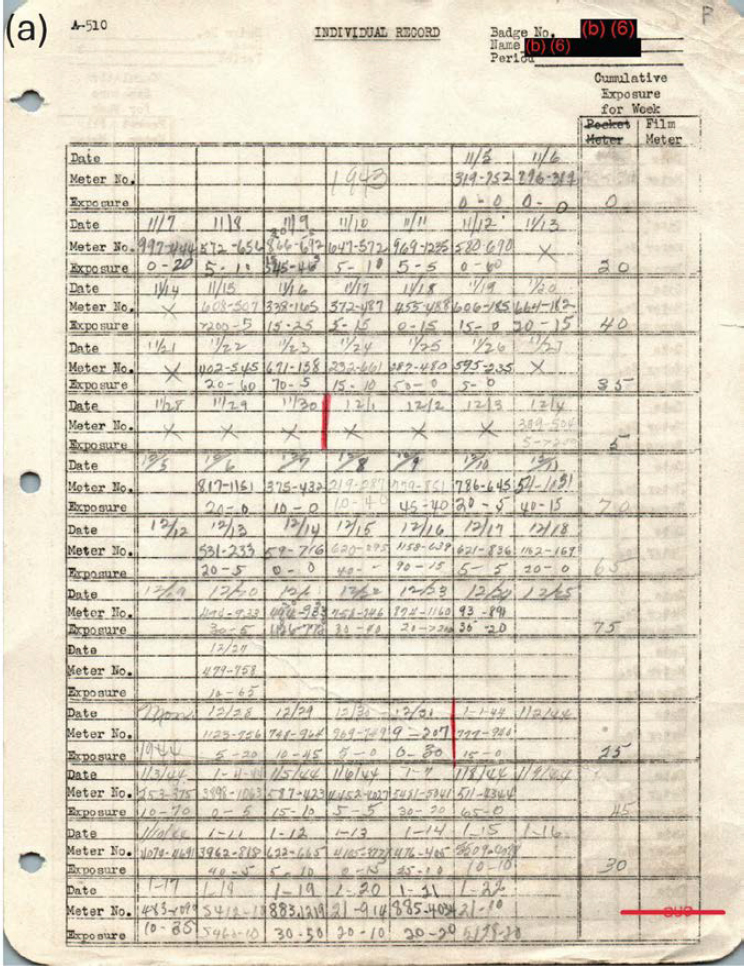

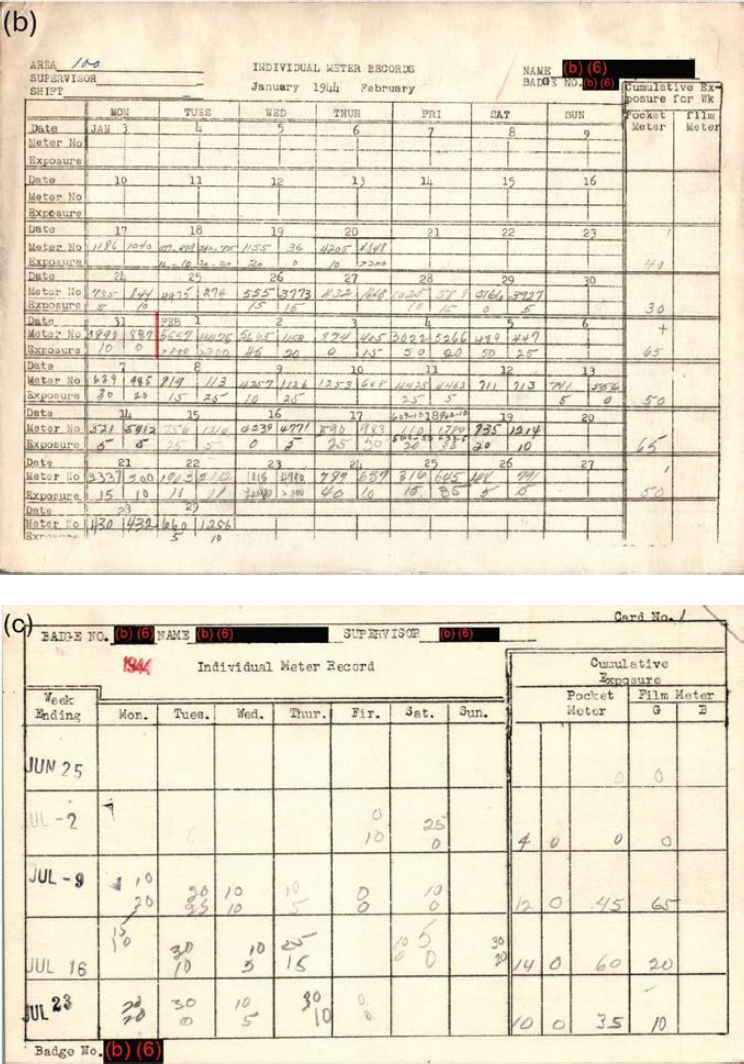

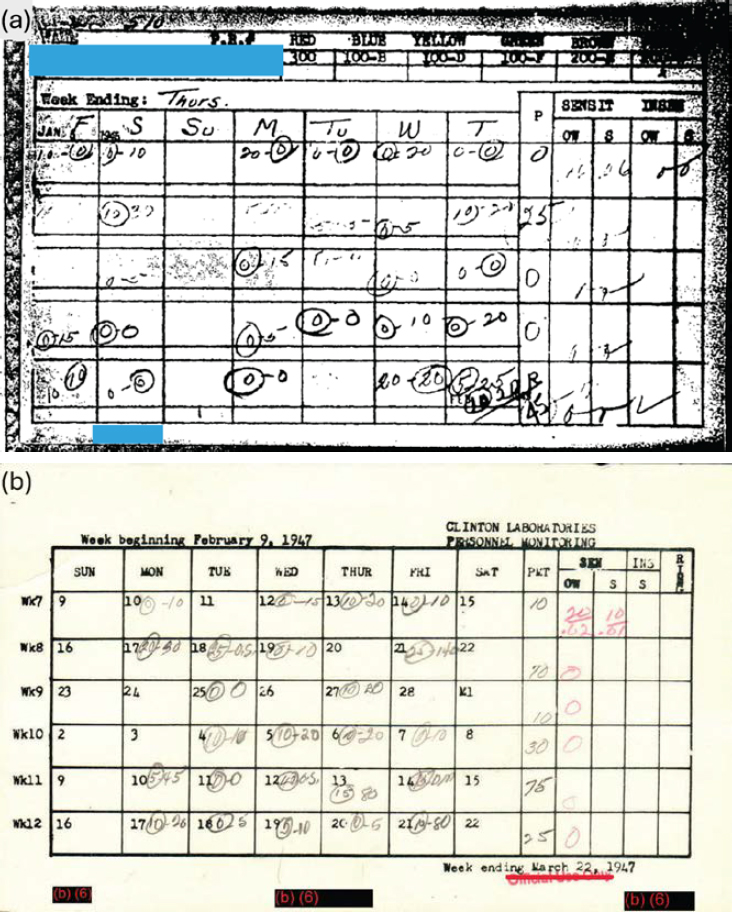

The presenters noted an evolution in dosimetry records from the beginning to the end of the Manhattan Project for types of dosimeters used and information captured and its quality and frequency. Some records were legible, while others were illegible or nearly so. For example, Figures 5-3a, 5-3b, and 5-3c depict early individual dosimetry records for a Clinton Engineer Works (Oak Ridge) worker in December 1943, January 1944, and June 1944, respectively. The units of the exposure were not recorded but, given the period, likely to be roentgen (R). In the December 1943 record (Figure 5-3a), the writing is difficult to read, and the pocket meter (PIC dosimeter) column is heavily faded. Furthermore, as is explicitly indicated in the January 1944 record (Figure 5-3b), two readings were recorded per day. In the December 1943 record, both are difficult to read and extract, as they are in the same cell separated by a dash, compared with the January 1944 record, which incorporates distinct cells for each meter and dates of record. By June 1944 (Figure 5-3c), the format changed to list only 5 weeks of exposure, still with two daily readings, which make it easier to read. The June 1944 record shows that the film dosimeter badge readings were broken out for gamma (G) and beta (B) radiation. For all three records, the cumulative exposure for each week is the sum of the lower meter readings for each day worked.

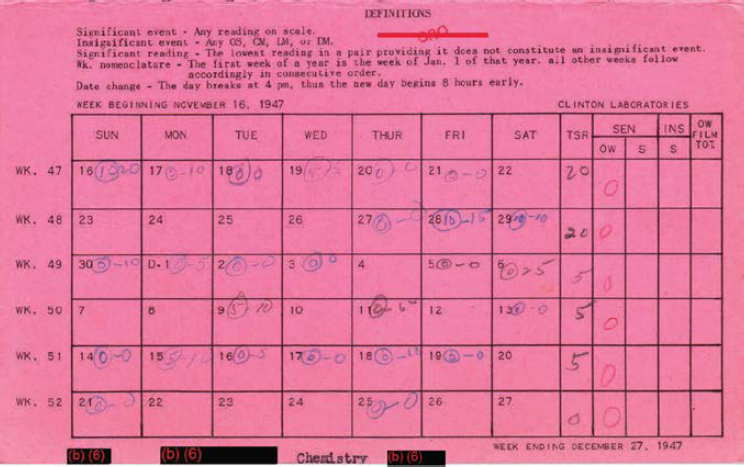

By 1945 the records were more detailed and becoming standardized across sites, as shown in Figure 5-4. The examples in Figure 5-4a and 5-4b are from Hanford and Oak Ridge, respectively.2 The information can still be difficult to read, depending on the clarity of handwriting and quality of the scanned image (if scans are provided), but the information is more complete and more standardized. This format of recordkeeping was maintained at least through 1947, as shown in Figure 5-5. Not seen in earlier records, the 1947 record provides a key for both film badge and pocket dosimeter symbols, which should be taken into account to understand potential issues with the exposure readings. As noted in the key in the record, different colors of pens were used also indicate the worker’s shift.

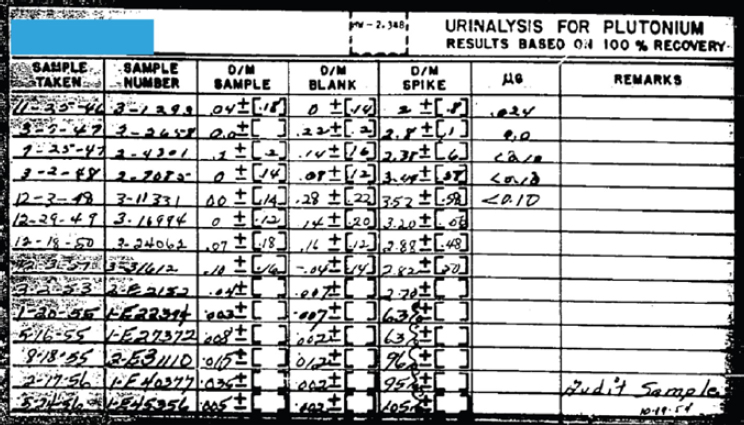

In addition to film and pocket meter records, the committee received a record of a plutonium urinalysis for a Hanford worker, shown in Figure 5-6; while readable, it is still difficult to interpret and could add to the time and labor involved in extracting its information. Urinalysis testing was not done on a set schedule, as noted in the history of the rollout of the internal monitoring/bioassay program. A researcher would need to determine how and when it was performed and if the frequency was reliable enough to

___________________

2 The committee did not receive an example of this type of record for Los Alamos workers.

NOTES: These examples show that smudges and fading affect the readability of even legible text in these records. Figures enhanced for readability.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Michael Stafford, Director Nuclear and Radiological Protection Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, June 18, 2024 (Stafford, 2024).

NOTE: Figures enhanced for readability.

SOURCES: (a): Presented by Timothy Taulbee, Associate Director of Science for the Division of Compensation Analysis and Support, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, March 7, 2024 (Taulbee, 2024). (b): Personal communication, Michael Stafford, Director Nuclear and Radiological Protection Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, June 18, 2024 (Stafford, 2024).

NOTES: The card is pink and the handwritten entries in several colors (blue, black, and red) make it difficult to read certain entries. Figure enhanced for readability.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Michael Stafford, Director Nuclear and Radiological Protection Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, June 18, 2024 (Stafford, 2024).

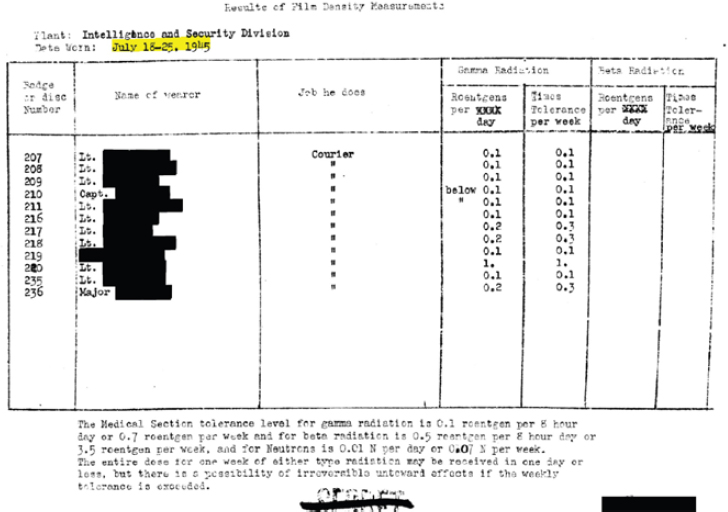

reconstruct the internal dose for that worker and the types of workers or jobs in general. Mathematical models may use bioassay measurements taken after the Manhattan Project to estimate the initial body burden when uptake occurred, cumulative dose equivalents received by various organs and tissues, and currently retained body burden; the latter estimate is unlikely for Manhattan Project veterans. However, these estimates are only possible if a specific veteran continued as an energy worker and had a known job history. While most records do not include military status, rank was occasionally noted, such as in Figure 5-7.

These examples highlight some of the limitations from the records alone; however, retrospective radiation dosimetry estimates have several other sources of uncertainty, such as completeness and accuracy. For example, in internal dosimetry, biases may arise due to problems with detector calibration, contaminated glassware, or improper assumptions about the nature of the intake itself. Biokinetic models themselves often rely on parameters extrapolated from animals or chemical analogues. External dosimetry estimates may rely on measurements from technologies with

NOTE: Figure enhanced for readability.

SOURCE: Presented by Timothy Taulbee, Associate Director of Science for the Division of Compensation Analysis and Support, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, March 7, 2024 (Taulbee, 2024).

less-than-optimal limits of detection. Documented cases show where a recorded zero exposure may actually signify unmonitored periods rather than no exposure at all (Wing et al., 1994). Additionally, workers may have missing raw data, such as misplaced dose record cards, so interpolation may be needed to estimate complete career doses.

Nonradioactive Chemical Exposure Records

Chemical exposure information for this period is limited, which would affect the ability to construct any robust epidemiologic study or risk assessment. During the committee’s information gathering near Hanford, Washington, Dr. Joyce Tsuji presented on the difficulties of chemical dose reconstruction for not only 1942–1947 but also the sites in the committee’s statement of task more generally. Chemical incident reports (i.e., exposure to high concentrations) exist but are often difficult to read (e.g., poor image quality scans or handwritten records) (Tsuji, 2024). Incident reports may include key information, such as building number or area, job title(s) of individual(s) involved, or the associated activity. The types of chemicals, processes, jobs, and facilities for this era are often characterized and described in aggregate using the same categories from the 1950s, as seen in the job

NOTES: The figure caption reads, “The Medical Section tolerance level for gamma radiation is 0.1 roentgen per 8 hour day or 0.7 roentgen per week and for beta radiation is 0.5 roentgen per 8 hour day or 3.5 roentgen per week, and for Neutrons is 0.01 N per day or 0.07 N per week. The entire dose for one week of either type radiation may be received in one day or less, but there is a possibility of irreversible untoward effects if the weekly tolerance is exceeded.” Figure enhanced for readability.

SOURCE: Presented by Timothy Taulbee, Associate Director of Science for the Division of Compensation Analysis and Support, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, March 7, 2024 (Taulbee, 2024).

exposure matrices presented in the University of Washington’s Workers Needs Assessment for Medical Surveillance of Former Hanford Workers (Barnhart et al., 1997). U.S. nuclear sites did not begin to develop chemical worker safety programs or collect and curate the same types of exposure records for general chemicals as they did for radiochemicals and radiation until the 1990s (GAO, 1981, 1983, 1990). In 1994, a DOE working group on chemical safety vulnerability report noted the inability to protect workers because of the lack of recognition of chemical hazards despite the use of many hazardous specialty chemicals (DOE, 1994). As noted by the cited documents, DOE had also been delegating worker safety to its contractors with insufficient

oversight resulting in inconsistencies in worker protection. The full program for chemicals consistent with Occupational and Safety Health Administration took effect in 2007 (DOE, 2006).

During its information-gathering sessions, the committee heard from records managers at Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos who discussed data access concerns due to the sensitive nature of the weapons manufacturing processes. For chemical exposure reconstruction to be feasible, a more in-depth understanding of the specific processes performed by each veteran would be necessary than is readily available, based on the information gathered by the committee. Researchers would need to be aware of all these difficulties in terms of the time and cost of analyzing these records. The examples in this section highlight the complexities of attempting to perform dose reconstructions of chemical, radiological, or combined exposures for Manhattan Project workers from this period.

EXAMPLES OF MANHATTAN PROJECT EXPOSURES

This section identifies notable exposures from the Manhattan Project based on available documentation. Depending on their job, veterans may have been exposed to a wide variety of toxic exposures including but not limited to: acids and acid vapors (e.g., nitric acid), beryllium, additional nonradioactive metals and metal compounds (e.g., aluminum, iron, nickel, cadmium, zirconium, silver, lead, and chromium), mercury, radioactive heavy metals and compounds (e.g., uranium-235, plutonium-239, americium-241), nonradioactive and radioactive gases and vapors (e.g., iodine, volatile organic solvents), and asbestos and silica (construction materials) (DOL, n.d.; Wing et al., 2004).

As mentioned in Chapter 3, a large portion of the Manhattan Project was concerned with producing fissile material, a critical mass of which is necessary for a functional nuclear weapon. Uranium was of primary importance because uranium-235 is fissile and uranium-238 can be transmuted into plutonium-239, which is also fissile, in a nuclear reactor. Nuclear fission is the splitting of a heavy nucleus into two lighter components, resulting in the formation of “new” atoms, fission products, that are typically radioactive. It also releases a few neutrons (which can induce subsequent fission events) and a large amount of energy. An array of isotopes of varying half-lives and decay types ultimately result due to decay (decay products) and/or neutron absorption (activation products) (Voillequé, 2008). To characterize a worker’s exposure, a researcher would need to understand both the radiological and chemical processes associated with producing and managing fissile material. The Department of Labor (DOL) Site Exposure Matrix (SEM) contains information on over 18,000 chemicals (both nonradioactive and radioactive chemicals and compounds) and covers 9 of the 13 sites in

the committee’s statement of task. The SEM is not time specific (it is an aggregate number of chemicals from a site’s inception to the present), so it cannot be used to identify when a chemical was present. Table 5-2 summarizes the number of chemicals ever used at each of the identified sites based on the SEM database. The chemicals are in many categories, including acids/caustics/reducing and oxidizing agents; dusts/fibers; explosives and explosive components; gases; metals; other materials; pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, and rodenticides; radiation and radioactive substances; and solvents. For sites in the SEM database, the number of chemicals (which includes radiochemicals) ever used ranges from a low of 30 (Uravan, Colorado) to a high of 5,417 (Ames, Iowa); at some sites, the number of chemicals was not captured (e.g., St. Louis sites and Monticello, Utah).

The wide range of potential exposures to veterans in the Manhattan Project and corresponding toxicities contributes to the complexity of evaluating these exposures; radionuclides have different physical, chemical, and biologic properties that influence their behavior in the body and how an individual might be exposed (Leggett, 2019). Moreover, biologic information on radionuclide exposures is available predominantly from comparatively high-exposure experiments in rodents, dogs, and, to a lesser extent,

TABLE 5-2 Number of Chemicals Reported at Statement of Task Sites in the SEM Databasea

| Site | Number of Chemicals |

|---|---|

| Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant K-25 | 1,371 |

| Oak Ridge Institute for Science Education | 1,131 |

| Oak Ridge National Laboratory (X-10) | 2,274 |

| S-50 Oak Ridge Thermal Diffusion Plant | 536 |

| Y-12 Plant | 1,106 |

| Hanford (1943–present)/PNNL (1965–2004) | 3,102 |

| Los Alamos, NM | 2,666 |

| Lake Ontario Ordnance Works (Niagara Falls Storage Site) | 540 |

| University of Chicago, IL (Argonne National Laboratory-East) | 1,727 |

| Iowa State, Ames, IA (Ames Laboratory) | 5,417 |

| Dayton Project | 597 |

| Uranium Mill in Monticello, UT (remediation) | 293 |

| Uravan, Montrose County, CO (Uravan #2) | 30 |

a The Department of Labor Site Exposure Matrix does not list St. Louis Airport Project Site, West Lake Landfill, or Coldwater Creek. However, it does list Mallinckrodt Chemical Company, which produced the wastes stored at those sites.

nonhuman primates (Ricciuti, 1969); extrapolation to humans and low doses is challenging. Individuals also have different physiologies that will influence their response to an exposure, including a radionuclide’s transport or chemical substance’s metabolism in the body (Applegate et al., 2020; Rajaraman et al., 2018). Adding to the complexity, many times, these combined exposures include not only external and internal radiation with possible internal metal (i.e., chemical) contamination but also exposure to other toxic substances in the same location and even at different times. Having limited information on the specific exposure, compounded with limited health outcome information (see Chapter 6), limits the type of study that would be feasible (see Chapter 7).

DATABASES AND SOURCES CONTAINING EXPOSURE INFORMATION

Many of the Manhattan Project sites and workers have been the subject of numerous studies, and extensive exposure information has already been captured in various databases over the past 80 years. However, no studies exist specifically of active-duty military or veterans and their exposures during the Manhattan Project in total or at a specific site. This section highlights resources that have been used for research on chemical and radiological exposures of energy workers (encompassing Manhattan Project workers). It summarizes the availability of record repositories, including their contents and the time periods they cover. None of the databases are specific to veterans or have an indicator to easily identify if or when a worker may have served in the military. However, as discussed in previous chapters, the majority of veterans who participated in the Manhattan Project were at Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos, and therefore, an assumption can be made that veteran records are included in the collections for all workers at these sites even if determining veteran status may not be possible. Several of the databases contain deidentified information. If a researcher is able to access the original dataset, which would have individual-level information, then a tier 1 assessment might be possible. Deidentified data can be used to support tier 2 and tier 3 assessments. Some datasets that have relevant exposures, such as the Beryllium-Associated Worker Registry, the Polonium Reconstruction and Plutonium Reconstruction databases, and the U.S. Army Dosimetry Center, do not cover the Manhattan Project time frame.

Comprehensive Epidemiologic Data Resource

CEDR is a DOE database that provides free access to deidentified datasets from health studies of DOE workers and environmental assessments

at DOE facilities. It is maintained by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) as an online repository. CEDR does not maintain any original records from DOE sites, but rather the record of research (i.e., the research work product as analytic data files) of site-specific studies. It includes over 80 epidemiologic studies involving more than 1.5 million workers at 34 sites, primarily focusing on data from major nuclear weapon production plants, including Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos (a set of these studies is included in Appendix D). Most studies examined mortality, particularly from cancer, in relation to radiation exposure and have detailed accounts of the types of chemical and radiological records. Dosimetry records of workers in many of these cohorts have also been compiled and are available in the CEDR datasets; these data have been analyzed in several peer-reviewed papers and may be available for future epidemiology studies. Several studies included in CEDR also collected confounding variables, such as smoking; however, these confounders are not necessarily recorded for 1942–1947, and veteran status is not available (Golden, 2024).

The on-going Million Person Study (MPS) aims to address the concerns of radiation occupation workers who received relatively low doses and at a more gradual rate (as opposed to acute exposures). CEDR is directly connected to the MPS in two ways. The first connection between CEDR and MPS is the utilization of existing CEDR records by the MPS to expedite updates to past studies by leveraging previous DOE efforts to study health effects in its nuclear workers (Ellis et al., 2022). This use of CEDR data requires permission from DOE in order to obtain identifying information about cohort members that is stored within CEDR but not publicly available. The second connection between CEDR and MPS occurs after the work of the MPS is completed to update, analyze, and publish results from each cohort. After publication, the updated cohort-specific data files are made available within CEDR. Some MPS cohorts include workers at some of the Manhattan Project sites during the years of interest, but the CEDR resources have no way to identify veterans that may have been part of the DOE cohorts at the sites relevant to this task.

Department of Labor—Site Exposure Matrices

DOL provides the SEM through its website: https://www.sem.dol.gov/expanded/SiteProc3.cfm. It is used to assist with claims under the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act (EEOICPA). SEM provides information about toxic substances, including both radioactive and nonradioactive chemicals, at various DOE and Radiation Exposure Compensation Act sites, the chemicals by job category as well as site, location, or building, and the potential health effects associated with exposure. The SEM database is structured to provide site-specific

information, which includes history, labor categories, processes that used toxic substances, areas and buildings where toxic substances were present, and incidents involving toxic substances. Epidemiologic studies can be conducted by comparing workers with occupations that involve exposure to a substance versus those who do not for health outcomes related to the substance.

However, this source has an important limitation. Despite its name, the database does not contain specific exposure information, that is, the route of exposure (inhalation, dermal, oral), intensity (concentration), duration, frequency, or amounts used at different times; it describes only whether a chemical was present at a given site and its health effects (IOM, 2013). The relationship between toxic substances and health effects in SEM are primarily derived from the Haz-Map database (haz-map.com), but not all substances in SEM have listed health effects and additional research may be necessary.

NIOSH Technical Documents for Special Exposure Cohorts

A special exposure cohort (SEC) was established under EEOICPA to automatically compensate certain groups exposed to radiation during their employment in the nuclear weapons complex (CDC, 2024a). The process involves identifying specific groups based on their exposure history, cancer types, and employment records. A group of employees may be added to the cohort or new groups may be created when NIOSH determines that dose reconstruction is not possible with sufficient accuracy and there are known exposures that could have harmed the class (NIOSH, 2005). NIOSH plays a crucial role by analyzing data related to worker exposure, including individual monitoring records and demographic information, to assess eligibility for inclusion in the SEC. Feasibility assessments are made for environmental, external, internal, and medical doses, often bounding the dose assessment for a given period and specific types of radiation (radioisotopes specific). These are useful documents for researchers interested in this area as a starting point for an evaluation of the availability of data.

An important caveat regarding NIOSH’s SEC ruling is that it analyzes data and performs dose reconstructions under a principle of “claimant favorability.” The overall evaluation and ruling emphasize the need for timely decision making, which requires balancing the thoroughness of exposure source characterization against the potential doses from each source. After an SEC is established, workers in that group that experience one of the 22 cancers identified by the program do not have to go through the exposure reconstruction process even if insufficient records exist for the worker either because of lack of monitoring (including sufficient internal bioassays) or missing records (CDC, 2024b). Of the Manhattan Project

sites that Chapter 3 highlighted as most likely to have a military presence, the following SECs have technical documentation: Hanford, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Dayton Project, Clinton Engineer Works (Oak Ridge), Oak Ridge gaseous diffusion plant (K-25), Oak Ridge National Laboratory/X-10, S-50 Oak Ridge thermal diffusion plant, and Y-12 (Oak Ridge).3 Therefore, if NIOSH has found dose reconstruction to be feasible, it is likely that enough data are available for at least a risk assessment (tier 3) analysis (as described in the tiers of exposure assessment section). However, if a dose reconstruction is determined to not be feasible, that does not necessarily rule out having enough data for an exposure assessment. Interpreting such data requires assuming conservative estimates to favor claimants when exact data are missing, adjusting for misclassifications or underreporting of dosage. A research team could potentially find enough data to perform a higher tier of analysis, but it may take more time and resources than what is needed for a compensation program.

Radiation Exposure Monitoring System and Radiation Exposure Information Reporting System

The DOE REMS is a comprehensive database that tracks occupational radiation exposures for all monitored DOE employees, contractors, subcontractors, and members of the public at facilities such as nuclear power plants, research laboratories, and medical institutions. Established to ensure compliance with radiation protection standards, REMS contains over 4 million exposure records, encompassing data from more than 775,000 individuals since 1986. REMS is managed by the DOE’s Office of Environment, Health, Safety and Security, with technical support provided by ORISE. It is updated annually, incorporating new exposure records and ensuring the data remain current for research and analysis. NIOSH uses REMS data to support radiation dose reconstructions for worker health assessments (OEHSS, 2024, 2025).

Closely related, REIRS is a comprehensive database maintained by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) that consolidates reports of occupational radiation exposure for individuals monitored by NRC-licensed facilities. Established to support NRC safety concerns, REIRS contains detailed records of radiation doses received by employees, contractors, and visitors (Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2024). The first annual report was released in 1976, containing exposure information back to

___________________

3 Special exposure cohort documents exist for additional statement of task sites that have lower probability of military presence: Ames Laboratory, Metallurgical Laboratory (University of Chicago), Lake Ontario Ordnance Works, and St. Louis Airport Project Site. The Dayton Project SEC is called “Monsanto Chemical Company.”

1969 (Johnson, 1978). The database includes personal information, such as names, Social Security numbers, birth dates, exposure dates, and radiation dose data, which are reported annually by licensees in accordance with 10 CFR 20.2206 (Hagemeyer, 1994; Hagemeyer et al., 2022).

REMS and REIRS are potential sources of worker exposure data to support epidemiologic studies. Notable limitations are that they lack assurances that they contain any flags of veteran status or health outcomes and do not cover the Manhattan Project. These databases would be useful in determining occupational exposures of veterans that remained working at a DOE site or NRC licensees after the Manhattan Project.

United States Transuranium and Uranium Registries

The primary purpose of USTUR is to collect, analyze, and preserve whole-body donations from individuals who have been occupationally exposed to radioactive materials, primarily workers from nuclear facilities during the Manhattan Project and other early nuclear research periods. The biosamples are used to study biokinetics, dosimetry, and possible biologic effects of actinides in humans. Study results are used to refine dose estimates and estimation methods in support of reliable epidemiologic studies, radiation risk assessment, and regulatory standards for radiological protection of workers and the general public. In its presentation to the committee, USTUR reported that of the 365 registrants in its database, 122 worked 1942–1947 at Oak Ridge, Hanford, or Los Alamos (some transitioned between sites). Of those 122 registrants, 19 self-reported military service at some point during their occupational career (nonspecific time) (McComish, 2024). The records belong to the individual sites, and each site would need to be contacted to obtain access. This database is unlikely to inform a tier 1 exposure assessment, but it could provide important data for dose reconstruction models for other tiers of analysis.

Data Access for Dosimetry Records

Access to dosimetry records for 1942–1947 is possible but has several challenges. For instance, the CEDR resource offers deidentified exposure data for radiation workers at many DOE sites. Because these publicly available datasets are anonymized, they have limited usefulness in drawing epidemiologic inferences. However, with considerable effort and appropriate permissions, it may be possible to track down and collect original datasets (before they were submitted to CEDR) that have identifiers for the individual-level data. Sites such as Hanford and Los Alamos have large occupational databases that include official worker exposures from the 1940s, but these records are not publicly available. Similarly, NIOSH and,

to a lesser extent, USTUR maintains exposure records from this period across a large variety of sites. These records are not publicly available, so obtaining them will require the proper levels of authorization, and they would need to be converted into a usable format, a resource-intensive task. Despite the necessity for authorization, many of the repository points of contact did express optimism that researchers could gain access to existing records. Therefore, site-by-site access to dosimetry records is possible but would require extensive levels of approval, time, and effort.

SYNOPSIS

The Manhattan Project involved numerous complex processes using toxic chemicals and radiological substances to produce the world’s first nuclear weapons. Each site played a unique role, and a researcher will need to understand that role and the major processes to know the full extent of the types of toxic exposures at that site. Depending on their job and location, military personnel may have had a wide variety of toxic exposures, including acids and acid vapors, beryllium, mercury, radioactive heavy metals (e.g., uranium and plutonium) and compounds, nonradioactive metals and metal compounds, and nonradioactive and radioactive gases and vapors (e.g., iodine, volatile organic solvents). Many processes were being performed for the first time under strict time constraints, and standards and practices for monitoring and recording worker exposures were being refined and developed in tandem. Chemical exposures were not well documented and often only reported as a result of a high exposure (incident report). However, the health concerns from radiological exposures were more widely recognized, and those exposures were documented to varying degrees at and across sites.

The committee found that little information is available that describes Manhattan Project–specific chemical exposures and these were infrequently recorded. Moreover, the chemicals and processes involved in the activities and weapons manufacturing process are sensitive, and access to these records and information is likely to be restricted.

For most radiological exposures, the Manhattan Project sites (particularly Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos) followed the radiation dosimetry program guidance from the Manhattan Engineer District’s Health Division and concurrently developed their own radiation protection guidance. Implementation of the guidance varied, as did the type and accuracy of dosimeters available. External radiation exposure monitoring is often available starting in 1943, but the dosimeters (and therefore information captured) continued to be refined throughout the Manhattan Project. This in turn means that not all external dosimetry records from the period are comparable, and the disparate measures would need to be converted to current units and measures, which may make it difficult to reconstruct the full external dose for an

individual. Furthermore, not all workers were given a dosimeter in the early years of the Manhattan Project, and daily monitoring records may contain gaps. This may result in early records being available only for veterans in specific technical jobs. Moreover, the records of dose reconstruction are not always digitized; owned by different sites, agencies, and offices; and often difficult to read (e.g., smudged, handwritten, and with abbreviations not always defined). The examples of exposure records 1942–1947 provided to the committee and what was presented by records managers and health physicists indicate that the records do not, in general, contain an indicator of military status.

The committee found that some records exist for radiological exposures for 1942–1947, but record gaps, inconsistent record maintenance, differences across sites, limitations in the dosimetry programs, and changing contemporary technology would all affect the time and effort needed to extract usable information.

The committee found that, in general, exposure records 1942–1947 do not often distinguish between civilian and military personnel.

The quality and quantity of available data related to exposures determine the type of study that can be conducted. The committee presented a tiered approach to exposure assessment, with each tier representing a different level of data availability and completeness. Given the heterogeneity of exposures across sites, exposure assessments for Manhattan Project military veterans would need to be conducted site by site and might require different tiers. Incomplete individual radiation exposure records and the need to use area monitoring or source characterization assessments pre-1943 preclude a tier 1 radiological exposure assessment, although a tier 2 or tier 3 assessment may be possible.

For chemical exposures throughout the entire Manhattan Project and radiological exposures pre-1944, area monitoring measurements or documents detailing the processes performed (if available) are the best source of exposure information for a site and its individual military personnel. A review of relevant job categories and associated activities could also provide exposure information to support a group-level exposure assessment (tier 2). However, some information associated with particular military jobs or processes for nuclear weapons will be restricted and cannot be used to build exposure models. A JEM may be used to systematically assess and quantify exposure to various workplace hazards across different jobs and sites by linking information about job titles with exposure estimates (obtained using monitoring or modeling) and estimate radiological, chemical, and combined exposures. Since the goal of retrospective exposure assessment is to develop estimates of dose for use in epidemiologic studies, the estimation of exposure histories (i.e., exposure as a function of time) of various job categories is critical. These job exposure histories are then

combined with worker employment or military job histories to obtain individual exposure histories that can be used in exposure assessment models.

When only group-level exposure data are available for a particular site, subareas of a site, or particular job classes, but no individual exposures were recorded or can be reconstructed, risk assessment (tier 3) may be considered. In a risk assessment, exposure information is combined with dose–response data from the peer-reviewed literature to estimate potential health risks associated with the measured exposures. Tier 3 would apply to internal radiation exposures that occurred during the Manhattan Project. Internal radiation monitoring was not common until 1945 or 1946, depending on the site, and limited to bioassay measurements that were often taken infrequently or only when exposure was suspected for a particular activity. It may be possible to reconstruct some earlier exposures from bioassay measurements, but individuals would only have these if they continued working for DOE after 1945–1946; it would also require knowledge of their job history to estimate an internal radiation dose.

Conclusion 5-1: Given limitations of exposure records and lack of indication of military status, the committee concludes that individual exposure estimates (tier 1) would not be possible for the Manhattan Project. Group-based exposure assessments (tier 2) could cover all chemical, radiological, and combined exposures. A risk assessment (tier 3) may be used if veterans’ job histories cannot be determined.

Many of the Manhattan Project sites, particularly Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos, and workers at them have been the subject of numerous epidemiologic studies or risk assessments that have used exposure information captured in various databases throughout the more than 80 years since the official start of the Manhattan Project. However, despite many studies, military veterans have not been the target population nor included as a stratum. Moreover, Manhattan Project–specific exposures are not the only types of exposures considered in these studies or databases.

Several databases and sources of chemical and radiological exposures, such as CEDR, SEM, and NIOSH support for the EEOICPA special exposure cohorts, are available. These resources are specific for DOE workers, including Manhattan Project workers, but none of them indicate military status specifically. As the majority of Manhattan Project veterans were located at Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos, it can be assumed that veteran records are included in the collections of records for all workers at these sites even if identifying veteran status is not possible. Several databases contain deidentified information, but access to the original dataset may be possible in some cases. However, without individual-level data, these databases would support at most tier 2 or tier 3 exposure assessments.

REFERENCES

Advisory Board on Radiation and Worker Health. 2009. Assessment of the Metallurgical Laboratory Special Exposure Cohort (SEC) Petition-00135 with special emphasis on the 250-workday criterion. Vienna, Virginia: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Applegate, K., W. Rühm, A. Wojcik, M. Bourguignon, A. Brenner, K. Hamasaki, T. Imai, M. Imaizumi, T. Imaoka, and S. Kakinuma. 2020. Individual response of humans to ionising radiation: Governing factors and importance for radiological protection. Radiation and Environmental Biophysics 59:185–209.

Auxier, J. A. 1980. Personnel monitoring: Past, present and future. In Health physics, a backward glance: Thirteen original papers on the history of radiation protection, edited by R. L. Kathren. and P. L. Ziemer. Pergamon Press.

Barnhart, S., T. Takaro, B. Stover, K. Durand, B. Trejo, C. Mack, and K. Ertell. 1997. Needs assessment for medical surveillance of former Hanford workers. Seattle, WA: University of Washington.

Brackett, E., and Ushino, T. n.d. Internal and external dosimetry of the early nuclear weapons workers. https://www.aahp-abhp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2016-pm2.pdf (accessed March 13, 2025).

Cantril, S. T., and H. M. Parker. 1945. The tolerance dose. Argonne National Laboratory.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2024a. Special exposure cohort (SEC). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ocas/ocassec.html (accessed May 15, 2025).

CDC. 2024b. FAQS: Special exposure cohort (SEC). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ocas/faqssec.html (accessed June 5, 2025).

Descatha, A., M. Fadel, G. Sembajwe, S. Peters, and B. A. Evanoff. 2022. Job-exposure matrix: A useful tool for incorporating workplace exposure data into population health research and practice. Frontiers in Epidemiology 2:857316.

DOE (Department of Energy). 1994. Chemical safety vulnerability working group report. Washington, DC: Department of Energy.

DOE. 2006. Chronic beryllium disease prevention program; Worker safety and health program. Federal Register 71(6931).

DOL (Department of Labor). n.d. Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs. https://www.sem.dol.gov/expanded/SiteProc3.cfm (accessed March 13, 2025).

Ellis, E. D., D. Girardi, A. P. Golden, P. W. Wallace, J. Phillips, and D. L. Cragle. 2022. Historical perspective on the Department of Energy mortality studies: Focus on the collection and storage of individual worker data. International Journal of Radiation Biology 98(4):560–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/09553002.2018.1547851.

EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). 2011. Exposure factors handbook: 2011 edition. Washington, DC: National Center for Environmental Assessment.

EPA. 2019. Guidelines for human exposure assessment. Washington, DC: Environmental Protection Agency.

Fjeld, R. A., T. A. DeVol, and N. E. Martinez. 2023. Quantitative environmental risk analysis for human health. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons.

GAO (General Accounting Office). 1981. Better oversight needed for safety and health activities at DOE’s nuclear facilities. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office.

GAO. 1983. DOE’s Safety and health oversight program at nuclear facilities could be strengthened. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office.

GAO. 1985. Personnel radiation exposure estimates should be improved. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office.

GAO. 1990. Nuclear health and safety: Need for improved responsiveness to problems at DOE sites. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office.

Golden, A. 2024. Review of ORISE Epidemiologic Studies and the U.S. Department of Energy Health and Mortality Studies Program. Presentation to the Committee on the Feasibility of Assessing Veteran Health Effects of Manhattan Project (1942–1947)–Related Waste, Oak Ridge, Tennessee. May 8. Guidance for requesting available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/about/institutional-policies-and-procedures/project-comments-and-information.

Hacker, B. C. 1987. The dragon’s tail: Radiation safety in the Manhattan Project, 1942–1946: Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hagemeyer, D. 1994. Experience with REIRS for the revised 10 CFR 20. Vienna, Austria: International Atomic Energy Agency.

Hagemeyer, D., G. Nichols, M. T. Mumma, J. D. Boice, and T. A. Brock. 2022. 50 years of the Radiation Exposure Information and Reporting System. International Journal of Radiation Biology 98(4):568–571.

Hastings, P. 2024. Charge to the Committee on the Feasibility of Assessing Veteran Health Effects of Manhattan Project (1942–1947) Related Waste. Presentation to the Committee on the Feasibility of Assessing Veteran Health Effects of Manhattan Project (1942–1947)–Related Waste, Washington, DC. January 10. Guidance for requesting available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/about/institutional-policies-and-procedures/project-comments-and-information.

ICRP (International Commission on Radiological Protection). 2007. The 2007 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Vol. 37, Annals of the ICRP. Exeter, UK: International Commission on Radiological Protection.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2013. Review of the Department of Labor’s site exposure matrix database. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jayjock, M. A., C. F. Chaisson, S. Arnold, and E. J. Dederick. 2007. Modeling framework for human exposure assessment. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 17(1):S81–S89.

Johnson, L. A. 1978. Occupational radiation exposure at light water cooled power reactors. Washington, DC: U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Kathren, R. L., and R. K. Burklin. 2008. Acute chemical toxicity of uranium. Health Physics 94(2):170–179.

Leggett, R. 2019. Biokenetic models. In Advanced radiation protection dosimetry, 1st ed, edited by S. A. Dewji and. N. E. Hertel. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Lewis, N. 2024. The Military at Project Y. Presentation to the Committee on the Feasibility of Assessing Veteran Health Effects of Manhattan Project (1942–1947)–Related Waste, Los Alamos, NM. September 25. Guidance for requesting available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/about/institutional-policies-and-procedures/project-comments-and-information.

McComish, S. 2024. Military Veterans at the USTUR. Presentation to the Committee on the Feasibility of Assessing Veteran Health Effects of Manhattan Project (1942–1947)–Related Waste, Hanford, WA. July 18. Guidance for requesting available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/about/institutional-policies-and-procedures/project-comments-and-information.

NCRP (National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements). 2018. Deriving organ doses and their uncertainty for epidemiologic studies (with a focus on the one million U.S. Workers and veterans study of low-dose radiation health effects). Bethesda, Maryland: NCRP.

NCRP. 2024. Commentary No.34 - Recommendations on statistical approaches to account for dose uncertainties in radiation epidemiologic risk models. Bethesda, Maryland: NCRP.

NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health). 2005. Special exposure cohort (SEC). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2005-143/default.html (accessed June 5, 2025).

NRC (National Research Council). 1995. Radiation dose reconstruction for epidemiologic uses. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2012. Exposure science in the 21st century: A vision and a strategy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nuclear Regulatory Commission. 2024. Annual report on occupational radiation exposure, NUREG-0713. https://www.reirs.com/0713.html (accessed March 31, 2025).

OEHSS (Office of Environment, Health, Safety and Security). 2024. Instructions for preparing occupational exposure data for submittal to the Radiation Exposure Monitoring System (REMS) repository. U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/ehss/articles/radiation-exposure-monitoring-systems-data-reporting-guide (accessed May 29, 2025).

OEHSS. 2025. DOE occupational radiation exposure monitoring for CY 2023. https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2025-01/OES%202025-01%20REMS%20CY2023%20-%20FINAL.pdf (accessed March 13, 2025).

Pardue, L. A., N. Goldstein, and E. O Wollan. 1944. Photographic film as a pocket radiation dosimeter. Oak Ridge, Tennessee: Argonne National Laboratory.

Parker, H. M. 1947. Health-physics, instrumentation, and radiation protection. Oak Ridge, Tennessee: Atomic Energy Commission.

Rajaraman, P., M. Hauptmann, S. Bouffler, and A. Wojcik. 2018. Human individual radiation sensitivity and prospects for prediction. Annals of the ICRP 47(3–4):126–141.

Ricciuti, E. R. 1969. Animals in atomic research. Oak Ridge, Tennessee: Atomic Energy Commission.

Richardson, D. B., and S. Wing. 1999. Radiation and mortality of workers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Positive associations for doses received at older ages. Environmental Health Perspectives 107(8):649–656.

Rocco, J. R., E. A. Stetar, and L. H. Wilson. 2008. Site conceptual exposure models, radiological risk assessment and environmental analysis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Seixas, N. S., and H. Checkoway. 1995. Exposure assessment in industry specific retrospective occupational epidemiology studies. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 52(10):625–633.

Seidel, R. 1993. Scientists in uniform—the Special Engineer Detachment. https://library.sciencemadness.org/lanl1_a/LANL_50th_Articles/10-29-93.html (accessed June 20, 2025).

Stafford, M. 2024. Follow-On to Historical Background for Assessing ORNL Staff Exposure Records (1942–1947). Presentation to the Committee on the Feasibility of Assessing Veteran Health Effects of Manhattan Project (1942–1947)–Related Waste, Virtual. June 26. Guidance for requesting available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/about/institutional-policies-and-procedures/project-comments-and-information.

Taulbee, T. 2024. Overview of NIOSH Exposure Records and Dose Reconstruction Methodology in the 1942–1947 Era. Presentation to the Committee on the Feasibility of Assessing Veteran Health Effects of Manhattan Project (1942–1947)–Related Waste, Washington, DC. March 7. Guidance for requesting available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/about/institutional-policies-and-procedures/project-comments-and-information.

Toohey, R. E. 2008. Scientific issues in radiation dose reconstruction. Health Physics 95(1):26–35.

Tsuji, J. 2024. Issues for Consideration in Reconstruction of Non-Radiological Exposures for Veterans at Hanford in 1943–1947. Presentation to the Committee on the Feasibility of Assessing Veteran Health Effects of Manhattan Project (1942–1947)–Related Waste, Hanford, WA. July 18. Guidance for requesting available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/about/institutional-policies-and-procedures/project-comments-and-information.

UNSCEAR (United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation). 2016. Sources, effects and risks of ionizing radiation. New York, NY: United Nations Publications.

Voillequé, P. G. 2008. 31 Radionuclide source terms. In Radiological risk assessment and environmental analysis, edited by J. E. Till and H. Grogan. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Watson, E. C. 1957. Weekly processing of pocket ionization chambers. Richland, Washington: Hanford Works.

Wilson, R. H., J. J. Fix., W. V. Baumgartner, and L. L. Nichols. 1990. Description and evaluation of the Hanford personnel dosimeter program from 1944 through 1989. Richland, Washington: Pacific Northwest Laboratory.

Wing, S., C. West, J. Wood, and W. Tankersley. 1994. Recording of external radiation exposures at Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Implications for epidemiological studies. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology 4(1):83–93.

Wing, S., D. Richardson, S. Wolf, and G. Mihlan. 2004. Plutonium‐related work and cause-specific mortality at the United States Department of Energy Hanford site. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 45(2):153–164.

This page intentionally left blank.