Evaluation of Manhattan Project Records for Veteran Health and Exposure Assessments (2025)

Chapter: 4 Identifying the Veteran Population

4

Identifying the Veteran Population

To describe the demographic characteristics and specific military characteristics and duties of veterans, they must first be identified. As discussed in Chapter 3, only 6 of the 13 Manhattan Project sites listed in the statement of task had a military presence (Oak Ridge, Hanford, Los Alamos, Uravan, Dayton, and Alamogordo before the Trinity test); these six sites are the focus of this chapter, which describes and identifies (including quantifying) the veteran population potentially exposed to toxic substances as a result of their duties. Approximately 500,000–600,000 people worked on the Manhattan Project during its officially recognized period, January 12, 1942–August 15, 1947 (Los Alamos Main Street, 2020; Wellerstein, 2013). At its peak operation in 1945, approximately 5,600 (~1%) of the project workforce were military personnel (Jones, 1985, p. 344). Some of them worked side by side with civilian employees and contractors in administrative, engineering, and scientific roles, whereas others were assigned purely military tasks, such as site security provided by military police. Regardless of task, all military personnel were assigned to a specific Army unit.

As a roster of Manhattan Project veterans is not readily available, creating one would be an important but challenging aspect of any potential epidemiologic study. Roster is a specific term used in this context to mean both an identification of service members and sufficient additional information (e.g., identifiers and military assignments) needed for a study linking exposures during the period of interest with health outcomes. A roster is a standardized, unchanging, and formalized collection of individuals compared with the more general list. Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos had the largest military presence, so the committee focused its efforts on these

sites to find service member information. As discussed in Chapter 3, some Manhattan Projects sites that are not listed in the statement of task had a military presence, but they are not considered further, as they are outside of the scope of this report. Identifying the veterans could be addressed by compiling a list of individuals assigned to Manhattan Project military units, but an ideal roster would also provide personal identifiers, such as military service numbers, rank, and specific locations and dates of service. The committee heard from invited experts and made information requests to determine how such a roster could be created. Military units systematically record the names and identifiers of individuals assigned to them for specified periods (usually monthly), as discussed later, and service members (and veterans after separation) have personnel files that detail unit assignment history. However, no crosswalk exists between individual service member–level data and military unit–level data, making it daunting to create complete rosters or develop population samples. Nevertheless, the former Department of Defense (DoD) Environmental Support Group compiled population data for studies of Vietnam veterans, such as the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (Kulka et al., 1988). The committee considered rosters compiled by independent researchers and organizations, including the Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) and the Atomic Heritage Foundation archive of Manhattan Project workers, to determine if they could be used or expanded to identify military veterans for an epidemiologic study.

This chapter begins by describing the units and detachments of military personnel who participated in the Manhattan Project sites of interest and provides an estimate of their numbers. The next section describes potential sources of records and the process that would be required to create a roster identifying all such veterans. To determine the extent of available data, the committee requested information from federal agencies and other organizations that potentially hold either military or non-military records of service members who worked on the Manhattan Project for the six statement of task sites with a known military presence. Information requests were sent to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Department of Energy (DOE), DoD, and others. The request for information from DOE headquarters led to further requests and presentations to the committee by field office record managers at the three primary sites (Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos) to determine whether site-specific data, such as employment rolls or medical surveillance programs, could yield information about service members. For each of these sources, the information requested and received is described, and instances of no reply to information requests are noted. As per the terms of this feasibility assessment, the committee was not permitted to collect records or conduct analyses but rather was asked to understand and characterize available records, including their contents and format. Findings from searches

of published materials, targeted information requests, summaries of invited presentations to the committee, and other information are described in the relevant sections of the chapter.

DESCRIBING THE MILITARY POPULATION

As one of its first tasks, and related to the first subtask, the committee attempted to approximate the number of military veterans “exposed to toxic substances” during the Manhattan Project and for those six locations with a known military presence. To estimate the number of individuals at each location, the committee focused on identifying first all types of military personnel who were assigned to the Manhattan Project and their associated units and then the individuals assigned to those units. The next section describes the types of military personnel assigned, including their units, documented personnel strength, deployment locations, and roles and jobs. Under the umbrella of the Manhattan Engineer District (MED) was the Special Engineer Detachment (SED; which consisted of scientists and technical personnel), Provisional Engineer Detachment (PED), military police, and the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) which all were under the 9812th Technical Service Unit Corps of Engineers (TSU-CE) after February 1, 1945. A few U.S. Naval personnel were assigned to the MED to support operations. Apart from WAC, which was comprised of enlisted women, these military groups were comprised of male service members.

Manhattan Engineer District

On August 13, 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers assumed direction of the Manhattan Project and established the MED in New York to manage this vast undertaking; General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., commanded it. After the Army Corps of Engineers assumed responsibility for process development, materials procurement, engineering design, and site selection for the Manhattan Project, it used both military personnel and private contractors to construct the development and production facilities, with civilians greatly outnumbering military personnel (Jones, 1985).

MED faced a prodigious challenge of identifying, recruiting, and training the vast numbers of technical personnel needed to develop a nuclear weapon. The assigned military personnel included many scientists and engineers already employed as civilians at the Manhattan Project sites, but they were inducted into the military for security and administrative reasons (OSTI, n.d.c). Other military personnel were recruited through the Army specialized training program, established in 1942, at some universities and colleges, and, beginning in 1940, through the “National Roster of Scientific and Specialized Personnel” compiled by the National Resources Planning

Board and the Civil Service Commission to mobilize academic and industrial science (Carmichael, 1944).

By November 28, 1942, 1,590 requests for specialized personnel had been received by federal government agencies, the war industry (i.e., mass mobilization of the entire U.S. manufacturing industry toward war production), and agriculture (including specialists in biology, veterinary science, husbandry, and agricultural sciences), and 136,593 names had been certified as scientific and specialized personnel in response to those requests, as documented in Scientists in Uniform WWII (U.S. Army, 1948). By January 1946, approximately 400,000 individuals were included in the National Roster of Scientific and Specialized Personnel (Carmichael, 1946). A 1944 article in The Scientific Monthly stated that as of February 1944, this national roster had “certified over 140,000 names of specialists to various agencies engaged in the war effort, including requests from the Army and the Navy for specialists to be made commissioned officers. More than 10,000 individuals have been directly offered commissions in the Army and Navy from the Roster’s rolls” (Carmichael, 1944, p. 143). However, only a few of these worked on the Manhattan Project, and they would not have been assigned to the sites of interest (Carmichael, 1944). The National Archives II holds the records of the National Resources Planning Board Divisions, which may include the actual list of names on the national roster (NARA, 1931–1943). Additional information or lists of names may be available in the NARA holdings of the War Manpower Commission (NARA, 1936–1947). Both resources may also contain information on locations where individuals were sent as part of the wartime scientific/technical effort, including those assigned to SED at the sites listed in the statement of task.

MED was a complex operation; the military structure varied at each site, and organizational hierarchies changed over time. Prior to February 1, 1945, the military police, PED, and WAC detachments reported to the Eighth Service Command Unit (SCU). Military police, PED, and those WACs not administered by Oak Ridge were assigned to the 4817th SCU; WACs administered by Oak Ridge were attached to the 1467th SCU (Jones, 1985, p. 361; U.S. Army, 1946a, p. S14). The Office of the Chief of Engineers directed general administrative functions for MED and gave the Manhattan Project its first military designation: the 9812th TSU-CE Manhattan Project (Truslow, 1973; U.S. Army, 1946a), effective February 1, 1945. The entire military portion of scientific and technical Army personnel assigned to MED, regardless of location, were assigned to the 9812th TSU-CE, which reported directly to the district engineer (U.S. Army, 1946a). The committee also identified some MED organizational charts, but these cannot be used to compile a roster because they do not identify the specific military units or dates of activation or strength, all of which are critical elements for an epidemiologic study.

President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 in 1941 to ban racial discrimination in employment by all federal agencies and all unions and companies contracted for war-related work, and this provided more employment opportunities for Black Americans within the Manhattan Project (Gardner-Chavis et al., 2016). However, the Army was segregated until 1948, when President Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which banned segregation in the armed forces. Additionally, different sites followed the cultural norms of the communities in which they were located, and therefore, had varying degrees of segregation and discrimination in hiring processes (Gardner-Chavis et al., 2016). For instance, in the 1940s, there were no Black military police units and few if any Black technical military personnel. Those Black scientists working on the Manhattan Project were most likely contractors rather than service members assigned to MED.

Special Engineer Detachment

Military personnel performed tasks that, for security reasons or lack of civilian workers, could not be assigned to contractor employees. Manhattan Project leaders expected problems with recruiting and retaining younger technicians and junior scientists who might be called to military service by spring 1943 (Jones, 1985). Labor shortages were exacerbated by competition with wartime production plants, other federally funded research programs, and the draft. It was proposed to establish a military command within MED to assign these technicians and junior scientists, once drafted. On May 22, 1943, the commanding general of the Army Service Forces approved creating SED within MED (U.S. Army, 1946a); recruitment began late in 1943. The initial authorization called for 334 enlisted men; this increased until a peak authorization in December 1945 of 6,032 (U.S. Army, 1946a). SED personnel were assigned to Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and other MED sites. They served multiple roles and functions, including as lab technicians, engineers, and scientific lab staff, depending on their skill sets and the needs at the time.

The Army Specialized Training Program Headquarters in Washington, DC, worked with the Manhattan Project, arranging clearances with universities for screening possible SED candidates and interviewing qualified Army Specialized Training Program students (Jones, 1985; U.S. Army, 1946a). The Office of the National Roster of Scientific and Specialized Personnel provided the names, education, industrial backgrounds, and military status of available and qualified scientific personnel from its records (Jones, 1985; U.S. Army, 1946a). Universities and colleges nationwide, particularly those with engineering schools, submitted the names and draft status of qualified graduate students. MED representatives screened and interviewed enlistees at Army camps throughout the country to identify and recruit personnel

for the Manhattan Project (Jones, 1985). Manhattan Project officials also reached out to other government agencies and private firms for information concerning former employees who were in the military and their draft status.

Even as recruitment moved forward for SED, the geographic distribution of MED made creating a centralized administrative point for the scattered SED personnel unlikely. Normally, these units would have been attached to the various area service commands for administrative purposes. However, the amount of site-specific classified information that needed to be made available to the service commands presented a security risk (Jones, 1985). Rather than create possible security breaches, Manhattan Project officials assigned administrative responsibility for enlisted personnel to the commissioned officers at the larger sites and to experienced noncommissioned officers at the remaining MED locations (Jones, 1985). Consequently, administrative policies varied at each specific location, and this structure led to additional compartmentalization of personnel and records.

At Oak Ridge, a peak of 1,176 SED personnel were spread across the Y-12 plant, K-25 gaseous diffusion plant, S-50 thermal diffusion plant, and X-10 graphite reactor (OSTI, n.d.d). Hanford had fewer SED than Oak Ridge or Los Alamos. Sources do not differentiate military personnel at Hanford, but the peak of MED, SED, and WAC personnel was 268 by June 30, 1945 (Cannan, 2001). At Los Alamos, SED service members “worked on everything from bomb design to inventory control, often in tandem with their civilian counterparts” (AHF, 2022) and by 1945 included over 1,800 men (AHF, 2014; Seidel, 1993). The Dayton Project had 30–40 SED members assigned to it (Gilbert, 1969). Whether SED personnel were at Uravan is unknown.

Eighth Service Command

The U.S. Army Eighth Service Command provided logistical support to various military units during World War II. Within it, two service command units specifically aided the Manhattan Project: the 4817th and the 1467th (Jones, 1985; U.S. Army, 1946a). Military police, PED personnel, and WACs not assigned to Oak Ridge were assigned to the 4817th SCU; it was formally transferred to MED on October 31, 1945 (U.S. Army, 1946a). WACs at Oak Ridge were assigned to the 1467th SCU.

Provisional Engineer Detachment

By November 1945, the 4817th SCU at Los Alamos had 108 officers, 2,517 enlisted men, and 236 WACs (McGehee, 2004; U.S. Army, 1946a). PED personnel were only located at Los Alamos and Alamogordo, and they

performed important roles in construction, operation, and maintenance of Los Alamos. Initially, they were selected to fill specific jobs, and they operated the power plant, steam plant, motor pool, garage, and mess halls and repaired and maintained all the buildings and roads (AHF, 2017; Truslow, 1973). They assumed positions in the commissary, post exchange, and post engineer office that could not be filled by civilians due to security concerns. They were also assigned to firefighting roles (AHF, 2017; Jones, 1985). Additionally, they were involved in constructing scientific and technical facilities at Los Alamos, including many of the critical test site areas. PED crews constructed many of the S-Site1 buildings, including the laboratory, shops, powder magazines, office building, steam plant, casting house, high explosives preparation buildings, and mess hall. They also built the facility at Anchors Ranch, another satellite technical area at Los Alamos, that cast containers for explosive charges (AHF, 2017; Truslow, 1973; U.S. Army, 1946e).

In April 1943, the PED detachment at Los Alamos had one officer and 43 enlisted men (Truslow, 1973). The initial unit was increased to 256 men and two officers to fulfill the needs of the expanding laboratory complex. PED again expanded to 465 men as more mess halls and motor vehicles were added and the power and steam plants enlarged. When PED was deactivated in July 1946, it had 302 enlisted men (Truslow, 1973; U.S. Army, 1946a).

Up to 45 PED personnel were sent to Alamogordo in 1945 in the lead-up to the Trinity test, and they served as mess hall crew, constructed and maintained buildings at the test site, kept the generators operating, and generally supported all activities at the base camp and the surrounding area. As the test date neared, additional PED personnel were sent to Alamogordo (AHF, 2017; Maag and Rohrer, 2003; White Sands Missile Range Museum, 2020).

Military Police

Military police detachments also served under the 4817th SCU and were assigned to the three primary sites. At Oak Ridge and Hanford, they provided security for technical and restricted areas and protected against enemy spies and saboteurs. The Hanford military police provided onsite security and accompanied the transportation of plutonium from Hanford to Los Alamos. On June 24, 1944, an arrangement between MED and the chief of staff of the Army service forces provided that one military police company, typically 62–190 soldiers, be assigned to both Hanford and Oak

___________________

1 S-Site (or Sawmill Site) served as the principal location for the development, testing, and manufacturing of high explosives casting and lenses for the nuclear weapon design.

Ridge (OSTI, n.d.e). The one for Oak Ridge arrived on July 2, 1944, and the one for Hanford arrived on July 4, 1944, to supplement DuPont’s Hanford Site Patrol. Military Police Detachment No. 2 took over perimeter patrol at Hanford in August 1944 and from 1943 to 1947 patrolled the site perimeter and barricades; secured the 213 Final Storage Magazine Building, construction camp, Midway Substation, and Hanford Ferry; and guarded classified shipments off site. Two military police officers were assigned to patrol the Richland Village, primarily on the weekends. In 1947, the military police slowly phased out the perimeter patrol, and their other security duties were transferred to the Hanford Site Patrol (Marceau, 2001; OSTI, n.d.e; U.S. Army, 1946a).

A Hanford military police detachment was assigned escort duty for the heavily armed convoys that used military ambulances to carry the plutonium to Utah for a handoff to similar convoys destined for Los Alamos. By 1946, however, a specially equipped rail car was used to transport the plutonium (U.S. Army, 1946c). A similar truck convoy system was used to carry uranium from Oak Ridge to Los Alamos and would have included officers in charge, enlisted military police, and counterintelligence agents acting as special guards. The motorcade met a convoy from Los Alamos at a halfway point and transferred the materials (U.S. Army, 1945a). Other truck shipments occurred between locations, such as the regular transfer of uranium hexafluoride from the Harshaw Chemical Company in Cleveland, Ohio, to the K-25 plant at Oak Ridge. These shipments were made in government trucks with armed auxiliary military police drivers dressed in plain clothes (U.S. Army, 1945a).

Los Alamos was a military undertaking from its inception, with assigned military police arriving in late April 1943 and numbering 7 officers and 196 enlisted men. By September 1943, 99 additional men had arrived. The increased personnel and expanding duties of the Manhattan Project unit led to adjustments in patrol lengths and duty systems. Personnel strength continued to increase as the site expanded, reaching a wartime peak of 9 officers and 486 soldiers. The military police were divided into four patrols of approximately 35 men. Each patrol had a sergeant in charge and served 8 hours on duty and 24 hours off duty (U.S. Army, 1946a).

Between May and December 1943, approximately half of the guards served inside the Technical Area as construction activities increased. These groups patrolled special buildings and the incomplete fence line. Once construction neared completion, the sentries were removed from inside the Technical Area, and two perimeter foot patrols and gate guards replaced them. By December 1946, the Los Alamos unit manned 44 full-time posts that required 115 men to be on duty every 24 hours. Additionally, due to the ongoing construction at the laboratory, escorts were needed, requiring five additional guards per day (U.S. Army, 1946e).

The Los Alamos military police also provided personnel to guard the Alamogordo Bombing Range/Trinity test site. That detachment secured it during the preparations for and the actual Trinity test on July 16, 1945.

Women’s Army Corps

In May 1942, Congress created the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps to support the work of the Army; however, these women were not considered members of the armed services. On July 1, 1943, the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) was established, and women became fully recognized members of the armed services, with the same ranks and privileges as male troops. The women from the auxiliary corps became members of WAC. An estimated 100,000 women were WACs, but only a small fraction of them were assigned to MED as part of the 4817th SCU (OSTI, n.d.b; U.S. Army, 1946d). Between 16–24 WACs were assigned to Hanford 1943–1945, generally to “production work” (Cannan, 2001, p. 2-12.9; NPS, 2023). The number increased throughout the war, with the Oak Ridge detachment reaching 370 in December 1945 and Los Alamos reaching 260 in August 1945 (OSTI, n.d.a; U.S. Army, 1946a). The MED WAC detachment was inactivated in October 1946 (OSTI, n.d.a).

Manhattan Project WACs served as librarians, clerks, telephone and teletype operators, cooks, drivers, hospital technicians, and scientific research staff who handled highly classified documents (McGehee, 2004; U.S. Army, 1945b). The security was strict and the hours long. As one WAC noted, “We had only two shifts and operated 24 hours a day, seven days a week” (OSTI, n.d.b). At Los Alamos, the working program for WACs was not well defined at first, and they were all put on “basic jobs,” although many of them had technical qualifications. Over time, however, WACs were placed in practically every department at the site. Several were engaged in scientific research, and many, as at Oak Ridge, were in positions handling highly classified material (McGehee, 2004; OSTI, n.d.b).

Naval Personnel

About 150 U.S. Naval officers2 with expertise in mechanical, chemical, and electrical engineering and chemistry and physics were assigned to

___________________

2 One of the appendices in this reference was unavailable but appears to have more detail. Almost all of the Naval officers were assigned to Tennessee Eastman Corporation (Oak Ridge); under the command of the District Engineer and assigned to a Naval “Special Project,” they were technically assigned to the Eighth Naval District. A few Naval personnel were at the Army District Engineer (U.S. Army, 1946a, p.118–121).

MED to support operations (U.S. Army, 1946a).3 Although few, the Navy officers played major roles in the ultimate success of MED’s task through the research conducted by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory at Anacostia Naval Air Station in Washington, DC, and the Philadelphia Navy Yard at pilot plants to test the feasibility of liquid thermal diffusion as a process to produce enriched uranium. This evolved into the S-50 thermal diffusion process at Oak Ridge, which was operated by Army SED personnel who were first trained at the Philadelphia pilot plant.

Naval personnel filled temporary roles in various units, including operating plants, the District Personnel Division, and the patents section. They peaked at 150 in July 1944 but gradually decreased as civilian replacements were found (U.S. Army, 1946a). By the end of 1946, eight Naval officers remained in MED. Unit records might be used to identify personnel records for these officers to determine other assignments they may have had related to Manhattan Project activities and related exposures.

Summary of Manhattan Project Military Personnel

The Army Corps of Engineers directed the Manhattan Engineer District (MED; synonymous with the Manhattan Project), a large, secret network of highly technical research and development sites across the United States. All military personnel who participated in the Manhattan Project were assigned to MED, regardless of duty location. Through its examination of documents, reports, and other references to the Manhattan Project, the committee identified that military personnel were assigned to three units, all under the MED umbrella. The majority of technical personnel were in SED, and, along with MED headquarters staff, assigned to the 9812th TSU-CE (U.S. Army, 1946a). SED personnel had heterogeneous duties and jobs within those roles and across sites.

In support of MED, two units within the Eighth Service Command were also assigned: PED personnel, military police, and WACs not at Oak Ridge were assigned to the 4817th and WACs at Oak Ridge were assigned to the 1467th. After February 1, 1945, all military personnel of MED were assigned to the 9812th TSU-CE (Jones, 1985; U.S. Army, 1946a). Although PED personnel only appear to have served at Los Alamos and Alamogordo, detachments of military police and WACs served at numerous MED locations, including the three primary sites of Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos.

___________________

3 Local supervision exercised from the Eighth Naval District was initially assigned by the District Office to the Military Personnel Section of MED, then by the Commander, U.S. Naval Detachment, and finally through the U.S. Naval Unit, Special Project No. 157, which was established via Special Order No. 104 of the District Engineer on June 17, 1944 (U.S. Army, 1946a).

While both technical and administrative personnel may have had civilian counterparts performing similar, if not the same duties, the military police and PED personnel would have performed jobs unique to military service. For example, during its information gathering, the committee heard that military police may have been stationed outside of the Hanford T-plant when unfiltered iodine-131 releases occurred (Napier, 2024). The diversity of job duties, and therefore possible exposures, makes a combined military cohort inadvisable.

The committee examined numerous historical documents and heard from several site-specific historians regarding Manhattan Project personnel. These sources generally cited authorized strength (not actual numbers of personnel) of a detachment for a specific year, often with a breakdown of ranks and duties at specified locations. It is likely that true and authorized strengths did not differ significantly, but without a complete roster, quantifying the number of veterans is more uncertain. Furthermore, a full accounting of the military presence at the sites in the statement of task would not include all military personnel who served in MED, as other MED sites also had documented military presence (see Chapter 3). Using the available historical authorized unit strengths by year and other information on the military presence at each site discussed in Chapter 3, including the estimated peak of 5,600 in 1945 (Jones, 1985), the committee estimates that approximately 10,000 military personnel participated in the Manhattan Project from 1942 to 1947 across all sites.

Military presence ranged from an estimated low of 30–40 SED members at the Dayton Project to several thousand service members at Los Alamos. These data are order of magnitude estimates and not counts. They also do not comprise a roster for an epidemiologic study, as they lack information about individual tasks and years of service.

In the next section, the committee discusses the most likely sources and methods for identifying individual veterans and creating a complete roster of veterans for the sites of interest.

POTENTIAL SOURCES AND METHODS FOR CREATING A ROSTER OF MANHATTAN PROJECT MILITARY VETERANS

This section describes several important sources of information that might lead to developing a nearly complete roster of Manhattan Project military veterans. Military records contain unit rosters and daily reports of action (also termed morning reports) of the technical service units and SCUs assigned to the Manhattan Project and are the most likely source of names and personal identifiers. Using that data, individual military records can be requested to provide additional information, including service dates and military jobs. The DoD Environmental Support Group successfully

used this approach to identify veterans and reconstruct unit rosters in a battalion tracking study of III-Corps Vietnam, 1966–1969 (NARA, 1997).

Rosters have been created for other veteran cohorts that could serve as examples (IOM, 2000, 2003). For example, the Five Series Study of mortality associated with military exposures to radiation from atmospheric nuclear weapons testing during the 1950s and 1960s assembled information from more than 100 distinct sources (IOM, 2000). Sources included handwritten paper logs, microfilm or microfiche, computer files, medical records, work orders, transport orders, memoirs, interoffice memorandums, testimony, secondary compilations of primary sources, letters from spouses, death certificates, film badge records, computer programs, and benefits and compensation claims. Staff from the National Academies and DoD staff and contractors made strenuous efforts to identify the existence of any relevant records, acquire them, and corroborate information using multiple sources. Data related to personnel movements, radiation exposure, and vital status were dispersed across the nation in cartons, computers, and file cabinets and under the authority of many federal, state, and local agencies. These data formed the basis of efforts to (1) identify individual members of the exposed and comparison cohorts, (2) ensure the comparability of these cohorts, (3) ascertain vital status and mortality information, and (4) compare the mortality experience of those cohorts while controlling for characteristics of individuals, military service, or time period that might influence mortality (IOM, 2000).

Data for developing a roster could also be contained in personnel or medical records at individual Manhattan Project sites if those files have indicators of whether an individual served in the military. Similarly, partial rosters may also have already been constructed for research studies, special exposure studies, or other administrative purposes. The committee sent written information requests to various federal agencies, research programs, and nonprofits dedicated to preserving Manhattan Project history, and to multiple historians to determine whether full or partial rosters existed that could be combined to identify military personnel at those sites known to have a military presence and create at least a partial roster.

In the sections that follow, the committee details its process and requests for information from these entities and summarizes the responses it received. In addition to the written information requests, the committee reviewed historic documents and reports and held information-gathering sessions of invited presentations and speakers to identify sources of information on veterans, their exposures, and health outcome records. Some records may have been maintained entirely by government contractors and not physically transferred to the pertinent federal agency. If the contracting company still exists, it may have some records in corporate archives; however, storage creates both a logistic and financial burden on the company,

so it is common to dispose of these records. The committee did not make requests to private companies that are successors of the companies that operated during the Manhattan Project at the sites of interest.

As the nation’s recordkeeper, NARA has a large collection of Manhattan Project records, and the National Archives at St. Louis4 is the central repository for military personnel records. The next section describes sources of military records, beginning with NARA overall and its National Archives at St. Louis, for creating a roster of Manhattan Project service members. This is followed by summaries of information available at DoD and VA. After sources of military records, other sources are described, including those held by DOE headquarters and field offices. Additional nonfederal sources were also considered, including rosters compiled by researchers and the Atomic Heritage Foundation.

Sources of Manhattan Project Military Records

To begin identifying sources of service members’ records, the committee submitted information requests and looked at where military records are held. The committee engaged with NARA and the National Archives at St. Louis, which is the central repository of both civilian and military personnel records; the Army Center for Military History; and VA. Each institution presents challenges regarding the availability of and access to its records. The intentional secrecy and functional compartmentalization of the Manhattan Project also contributes to the difficulty in identifying all relevant personnel and records.

National Archives and Records Administration

Among the foremost stewards of records pertaining to the Manhattan Project is NARA. It organizes, preserves, and makes these records publicly available by categorizing them into collections of related material (record groups). Manhattan Project–related materials are stored in multiple locations and include handwritten and typed records, ranging from wartime and postwar military memorandums, reports, and contemporary histories to research data files, letters, and logs documenting daily activities, protocols, and procedures; still and moving-image sources;

___________________

4 The National Archives at St. Louis retains the legal and physical custody of federal records that have been accessioned into, and thereby owned by, NARA, which allows these records to be open to the public. The St. Louis-based National Personnel Records Center of NARA is responsible for maintaining and answering record requests on behalf of the agencies; these records are still owned by the agency or branch of service and are not open to the public. Personal communication, Theresa Fitzgerald, Personnel Records Division Director, National Archives at St. Louis, May 30, 2025.

and interviews with Manhattan Project researchers. While many of these records are processed—meaning that archivists have organized, described, and preserved them for public access and research—some are in the same condition as when they were received, and archivists have not yet examined them.

In a joint memorandum of the Office of Management and Budget and NARA, issued December 23, 2022, federal agencies were directed to transform all permanent records not yet accessioned to NARA to an electronic format by June 30, 2024, for accession. It also directed federal agencies to manage all temporary records5 in an electronic format or store them in commercial storage facilities (unless they are transferred to a NARA federal records center). Finally, it directed NARA to issue guidance that allows federal agencies to move toward fully electronic recordkeeping, including policies to help them digitize permanent records from analog formats (Young and Wall, 2022). Simultaneously, NARA is digitizing its own collections. As of March 2024, NARA has some electronic World War II records, including on casualties, prisoners of war, enlistment and draft, duty locations for Naval intelligence personnel, Japanese Americans relocated during the war, and U.S. soldier surveys for 1942–1945 (NARA, 2022).

NARA and other archival organizations create and provide informational tools (finding aids) that summarize the content of record groups organized by folders within each record group, but the finding aids are limited to high-level content information. Using these finding aids, the committee identified record groups 77 and 326 as most relevant to its work, although other useful groups may be uncovered.

- Record group 77 contains records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers (NARA, 1789-1996), including the World War II–era work of the Army Corps of Engineers, and specifically “Records of the Manhattan Project Organization, 1940–1961 (bulk 1942–1946)” (NARA, 1940-1961). As of March 31, 2025, it has 143,317 textual scans online of the 163,045,325 total text pages, meaning that only 0.09% of the text has been digitized from this record group; more relevant data may become available (NARA, n.d.a).

___________________

5 All records stored by NARA are divided into one of two categories: permanent or temporary. Permanent records are kept by an agency until the end of a specified retention period, when they are legally transferred to NARA. Temporary records are destroyed at the end of their retention period. The records are put on a schedule that is jointly approved by the owning agency and NARA and specifies how long the records will be held before being destroyed. Holds and freezes may suspend the disposition cycle for particular temporary records (NARA, 2021). Government temporary records are routinely destroyed due to the lack of space, but efforts are being made to digitize them. Agencies must receive NARA’s approval before converting permanent or unscheduled originals to microfilm (Bosanko, 2024).

- Record group 326 contains records of the Atomic Energy Commission (NARA, 1923-1975), including its predecessor agency, MED. It is physically split between multiple NARA sites; a large portion is in the College Park/Archives II facility, but holdings in Atlanta, San Francisco, and Seattle have been described as including personnel information. The national archives in Atlanta identified seven folders within four series within the record group that may have records related to military personnel at MED sites during the 1940s.6 As of March 31, 2025, 110 textual scans appear online of 22,855,975 total textual pages, meaning that less than 0.001% has been digitized and pointing to the potential of further relevant data becoming available (NARA, n.d.b).

Physical copies of NARA records are stored in boxes at the same location. The boxes contain information cards that detail the contents of the box but may not fully characterize the contents, necessitating a physical search to locate a specific record. Additionally, once a box or series of boxes is located, the surrounding boxes may have relevant information that was not identified in the initial catalog search and may be overlooked if the boxes are not opened and examined. A search for the necessary records related to veteran health outcomes and Manhattan Project–related exposures will likely involve intensive labor by researchers to examine the contents of numerous boxes.

The Epidemiological Moratorium, established on March 15, 1989, places a moratorium on destruction of DOE epidemiologic records, including records associated with environmental monitoring; health and safety; administrative organization and management; process and material control; and work history, assignments, and locations. Although any records that were destroyed before this moratorium will not exist, potentially relevant records that could inform a future study may still exist and will not be destroyed while it remains in effect (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2021).

National Archives at St. Louis

The National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) and National Archives at St. Louis maintain records that are in the legal custody of NARA and available for research; 56 million are official military personnel records (NARA, 2011), including military unit rosters and morning reports. These records have not been used to compile a roster of the individual military

___________________

6 Personal communication, Jay Bosanko, deputy archivist of the United States, National Archives and Records Administration, June 3, 2024.

service members who participated in the Manhattan Project, which may be difficult because unit roster records for 1944–1946 were destroyed in 1975 by the Army, according to its retention schedule and due to storage space limitations. The committee heard that specific sites, such as Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos, may have created unified military rosters, but the secretive nature of the Manhattan Project and personnel movement meant that they were not consistently made, nor were they within NARA’s holdings or found at these sites when the committee conducted its information gathering. Installation-specific directories or lists of personnel are rare and may not exist for the Manhattan Project sites (Fitzgerald, 2024).

The National Archives at St. Louis performs some limited research services for the public, primarily providing information about its records, making the records (or microfilm) available in its research facilities, and assisting with ordering copies of available records. However, for more extensive research projects, as this would be, NARA may have a more direct role, or researchers experienced in working with these records may be available for hire (NARA, 2023b). The committee heard from one such group, Footsteps Researchers, to gain insights into the record retrieval process (Vicat, 2024). These researchers are trained through a program at NARA that teaches them how to handle older records. Once trained and given a research task, they submit requests for documents to NARA for physical copies of documents. They receive the documents onsite at a NARA facility and can scan and file them in their own databases. These researchers are experts in understanding historical military structure, reading code used on military records, and completing research using supplementary sources, such as ancestry.com or newspapers.com.

As described in the previous section, the three relevant military units for the Manhattan Project were identified as the 9812th TSU-CE (SED), and within the Eighth Service Command, the 4817th SCU (PED, military police, and WACs not assigned to Oak Ridge) and 1467th SCU (for WACs assigned to Oak Ridge). All Army unit records and morning reports located in St. Louis belong to Record Group 64 (Fitzgerald, 2024). In response to a committee information request, National Archives at St. Louis provided a listing of unit rosters and morning reports by year for the three units (see Table 4-1) and example scans of them.7 Although the dates of inclusion for this feasibility assessment are January 12, 1942–August 15, 1947, National Archives at St. Louis grouped 1940–July 1943. The table shows that unit rosters and morning reports are not consistently available for 1942–1947, with no other source for them. Notably, no unit rosters are available for any of the three units for 1944–1946—the years of highest Manhattan Project activity.

___________________

7 Personal communication, Theresa Fitzgerald, Personnel Records Division Director, National Archives at St. Louis, March 25, 2025.

TABLE 4-1 Unit Records and Morning Reports by Year for Manhattan Project Military Personnel

| 1940–July 1943 | Aug–Dec 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Record | ||||||

| 9812th TSU Rosters | Yes (1) | Yes | No | No | No | Possibly (2) |

| 4817th SCU Rosters | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Possibly (2) |

| 1467th SCU Rosters | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Possibly (2) |

| Morning Report | ||||||

| 9812th TSU | Yes (1) | |||||

| 4817th SCU | Yes (3) | Yes (4) | ||||

| 1467th SCU | Maybe (5) | Yes (6) | ||||

| Other | ||||||

| “Man Engineer Dist” MR | Yes | Yes (7) | ||||

NOTES: This information was provided in kind by Theresa Fitzerald in response to the committee’s request for information from National Archives at St. Louis. Blank cells indicate that more research would be needed to determine availability of those records. 1) Encompasses ALL Manhattan Project locations, providing a separate card for each one. Most begin June 1945, except for Washington, DC, and Oak Ridge. 2) Rosters for 1947 onward were filmed in January and July. 3) Aug–Dec 1943 Located Santa Fe, New Mexico, Station code 8365. 4) Santa Fe, New Mexico. 5) Only listing is 1467 Engr. Maint. Colorado. 6) Ft. Oglethorpe, Georgia. 7) Station Code “4878” seems to be a “catchall” for much of the Manhattan Project.

SOURCE: Committee adapted from information received from Theresa Fitzgerald, Personnel Records Division Director, National Archives at St. Louis, March 25, 2025.

Unit records for MED appear to be available for 1942 (when it was created) through 1943. Records for the 9812th TSU-CE, 4817th SCU, and 1467th SCU are available for 1942 and 1943 and possibly 1947 (for those detachments still active by then). Availability of morning reports do not appear to correspond to the same years as for unit records, except for the 4817th for August–December 1943. As shown in the examples, using the 1467th, records are available for October 1943, when it was at Fort Oglethorpe (not one of the sites of interest but a large base for service members who were passing through to duty stations), but the morning reports are for May 1943, so not an exact correspondence or match in terms of time. However, as this is a feasibility assessment and the information on these units and associated records was searched in kind, more information and exact time frames of records may be available for a formalized research project.

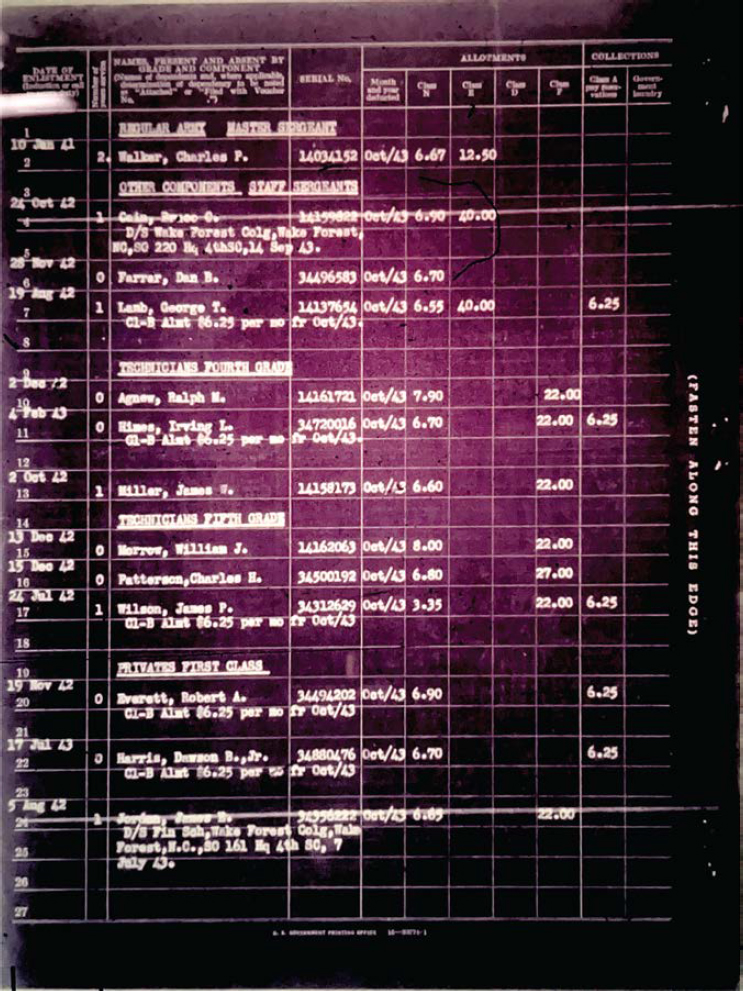

To compile a roster, one would start with a list of units by their official number and name and dates of interest. The unit record for the first month (e.g., January 1942) would become the basis of a roster of individual names (and service numbers). Each subsequent monthly report for the unit would be used to build the roster; these reports could also provide time in unit at the month level so that it might be possible to see when individuals entered and left the unit and possibly entered and separated from service. Ideally, the monthly unit report would be accessed and reviewed for the total time of interest; for the committee’s task, this would be 60 months (ending August 1947). However, Table 4-1 shows that records are not available for a large portion of that time. The available unit rosters for the Manhattan Project have been digitized by NARA, and examples of some of these were shared with the committee. Figure 4-1 shows an example of one of 16 pages for the 1467th SCU record for October 1943. It has been scanned onto microfilm and, of the 16 pages, is the clearest to read. From these unit records, which were primarily used for payroll, information for individuals by date of service entry (enlistment), grade and component, service number, month and year of detachment, and pay and other provisions is listed.

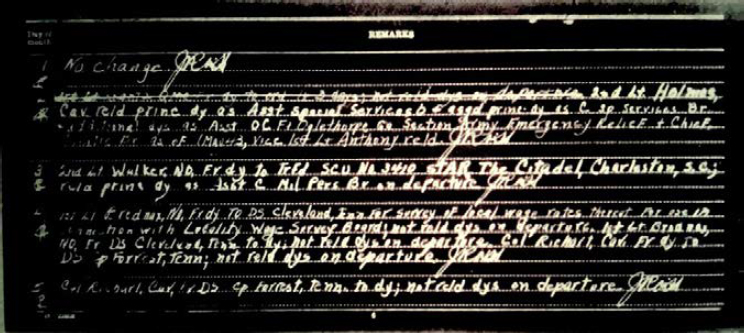

The roster generated from the monthly unit records may not be complete, even if they were available for the full period. Morning reports, available for all Army units in World War II, are a primary source of data. These reports documented status changes at the company level for individuals assigned to the unit and include unit assignment change, promotion, transfer, disciplinary action, or wounds received in combat (Golden Arrow Research, n.d.). They are not intended to be a full roster. Figure 4-2 shows an example of a morning report for the 1467th SCU for May 1943. The full morning report is eight pages, and the example page is the clearest to read. The morning reports have been scanned to microfilm, many from handwritten documents. Table 4-1 shows that they are not available for any of the three units for 1946 or 1947. They appear to be available for the 4817th SCU for August–December 1943 and 1944. For the WAC detachment at Oak Ridge, as part of the 1467th SCU, morning reports are available for 1944, but only Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, not Oak Ridge, Tennessee, is stated.

Each change in the morning report is noted by a code that would have to be interpreted by a research team. These reports contain important details to help track veterans who worked at Manhattan Project sites, as each report lists the name, rank, service number, unit designation, geographical location, and map coordinates for each veteran (Golden Arrow Research, n.d.). Only individuals with changes are listed. However, the reports can be used to track service members and their unit on a daily basis, as the report (during World War II) lists the record of events for the unit, including strength, rations, and commanding officer’s signature (Golden

NOTE: Figure enhanced for readability.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Theresa Fitzgerald, Personnel Records Division Director, National Archives at St. Louis, March 25, 2025 (U.S. Army, 1943b).

NOTE: Figure enhanced for readability.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Theresa Fitzgerald, Personnel Records Division Director, National Archives at St. Louis, March 25, 2025 (U.S. Army, 1943a).

Arrow Research, n.d.). These reports were handwritten until 1943, when the Army required them to be typed. They are stored on microfilm at the National Archives at St. Louis; however, they may be degraded and difficult to read (Golden Arrow Research, n.d.), as seen from Figure 4-2. NARA and VA use the morning reports to verify benefits eligibility for veterans whose service records were burned. Morning reports for 1940–1943 should be online in the NARA catalog. Reviewing them could help complete the roster that was started from unit records for the years that morning reports are available. These reports would also likely indicate the time each individual spent at each Manhattan Project site and other sites (potentially relevant to statement of task subtask 4).

Potentially Valuable Data Linkages

In 2024, NARA announced expansion of its joint digitization effort with Ancestry.com, a multiyear agreement to “digitize, index, and publish tens of millions of historical United States records, previously unavailable online” (NARA, 2024b). National Archives records to be digitized through this public–private partnership include U.S. military morning reports from World War II (NARA, 2024b).

National Archives at St. Louis stated that the time that the search and retrieval take in response to a records request depends on the digitization of hard copies and whether information lost in the 1973 fire can be recreated.

Conducting research in the National Archives can be time consuming, especially when records are not available digitally. Because many of the MED records and related materials may not be digitized, searching through them for relevant information to extract is likely to be laborious. Furthermore, as NARA notes, “Photocopies of the filmed images are often illegible . . . due to poor quality of the film reproduction, we [NARA] do not offer photocopies of microfilmed rosters or morning reports through the mail, nor do we offer to sell duplicate reels of morning report microfilm” (NARA, 2024a). In addition, these primary records for 1944–1946 will not be available from NARA because they were destroyed in 1975 in accordance with the general records schedule. Thus, it is likely that complete unit histories based on primary sources may no longer be available. However, secondary and tertiary records may provide nearly complete rosters, as described later. Additionally, the availability of efficient means of digitization and data extraction may aid in review of records for constructing the roster.

In response to a request from the committee, Jay Bosanko, deputy archivist of the United States, provided access to files from several NARA locations for the committee’s review. These included organizational structure of MED’s medical departments at several sites, but this is a small number of total MED personnel. However, the committee determined these files did not have information that would aid in quantifying the veteran population or creating a roster of Manhattan Project veterans.8

Linking Unit Histories to Personnel Records

Every member of the armed services has an official military personnel file, which is created for administrative functions; sections of these records are publicly available. The National Archives at St. Louis manages all official military personnel files for veterans with a separation date (discharged, deceased, or retired) of 62 (or more) years ago (NARA, 2024a); these files are accessioned to NARA by DoD and given permanent status.9 This is the culmination of 1942–1966 work to gather all former civilian and military personnel records under one administrative unit. These files, which include military health and medical records of discharged and deceased veterans, retirees, and military family members treated at military service medical facilities (NARA, 2025), are permanent records as of July 8, 2004. The quality and even what types of records are available for an individual vary

___________________

8 Personal communication, Jay Bosanko, deputy archivist of the United States, National Archives and Records Administration, June 3, 2024.

9 For service members with a separation date of less than 62 years (rolling date), their physical records are maintained by National Personnel Records Center, but the legal custodian of these records is the creating service branch (Fitzgerald, 2024).

widely. In the NARA organization system, official military personnel files are arranged by name, service number, or a NARA-unique identifier; no indicator identifies individual personnel associated with the Manhattan Project in any of the World War II records (Fitzgerald, 2024). The official military personnel file generally contains basic demographics; job titles (military occupation specialty); assignments, locations, and dates of service for each unit in which they served; training; qualifications; performance; awards and decorations; disciplinary actions; and administrative remarks. It may also contain birth certificates, marriage certificates, divorce decrees, letters, photographs, and discharge forms used by the military before 1950, the latter of which could help provide exposure information (Fitzgerald, 2024). Notably, detailed information about an individual’s participation in combat and military engagements is not in the official file; this information would be part of unit records and morning reports (Fitzgerald, 2024). Deceased veterans’ claim files contain post-service medical and clinical care information.

Access to and the completeness of these personnel records may be compromised because in July 1973, a fire in the National Archives at St. Louis Military Personnel Records building destroyed approximately 17 million official military personnel files, including 80% of the files for World War II and post–World War II Army personnel discharged between September 8, 1939, and December 31, 1959 (Fitzgerald, 2024). After the fire, NPRC initiated several records recovery and reconstruction efforts, including establishing a new branch to deal with damaged records (NARA, 2023a). These efforts included searches through sources both inside and outside of NPRC for supplemental documentation to reconstruct service information, which included VA claims files, individual state records, multiple name pay vouchers from the Adjutant General’s Office, Selective Service System registration records, burial files, pay records from the Government Accountability Office, and medical records from military hospitals (NARA, 2023a). As no duplicate copies of these records were ever maintained, nor any indexes created before the fire, no complete listing of records that were lost exists (NARA, 2023a). Therefore, it is unknown how many records for individual service members who worked on the Manhattan Project were affected by the fire.

While the National Archives at St. Louis records room in St. Louis normally allows researchers to view up to 12 records per day, for a special project, such as creating this roster of veterans, it does not impose a limit.10 These files are all now digitally delivered, but availability depends on how quickly staff can reconstruct the burned files.

___________________

10 Personal communication, Theresa Fitzgerald, Personnel Records Division Director, National Archives at St. Louis, December 20, 2024.

Department of Defense

DoD does not appear to maintain easily accessible complete rosters of individuals who served in particular units over the entire course of a conflict. After passage of the 2022 Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act, VA contacted DoD’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Nuclear Test Personnel Review Program,11 to ask whether it held records or information regarding the Manhattan Project. The program responded that it did not have records for individuals who participated in the Manhattan Project (Hastings, 2024). The committee noted this response and did not make its own request of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency. Knowing that the DoD Environmental Support Group (and its successor the U.S. Armed Services Center for Unit Records Research) had supported efforts to identify specific battalions and individual service members in those units to create rosters for epidemiologic studies for exposure to herbicides in Vietnam and other studies of military exposures,12 the committee considered whether similar efforts had been undertaken for the Manhattan Project. However, the Center for Unit Records Research and its successor, the Joint Services Records Research Center, closed more than 15 years ago, and so is not a potential source of information. Thus, based on information-gathering sessions with researchers familiar with unit records and morning reports, although it does not appear that DoD maintains copies of unit records, especially dating back to the Manhattan Project, a request could be made to the DoD Assistant Secretary for Health Affairs for additional details about the existence of a locator system for tracking all personnel (U.S. Army, 1946a) and whether site-specific rosters exist, any records 1942–1947 contain health records for active-duty service members, and if individual service discharge forms are available.13 Because the committee was not permitted to collect data or records or charged with actually creating a roster, it did not believe that making such a request of the Assistant Secretary for Health Affairs was appropriate for the feasibility assessment; however, future investigators may choose to do so. The committee also sent an information request to

___________________

11 Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Nuclear Test Personnel Review Program, is the same source used in the Five Series Study to compile a cohort of veterans (IOM, 2000).

12 Personal communication, Donald Hackinson, former director of DoD Center for Unit Records Research, June 4, 2024.

13 Military discharge forms used before 1950 (replaced by the DD 214 and related) include WD AGO 53 (Enlisted Record and Report of Separation Honorable Discharge), WD AGO 55 (Honorable Discharge from the Army of the United States), WD AGO 53-55 (Enlisted Record and Report of Separation: Honorable Discharge), NAVPERS 553 (Notice of Separation from U.S. Naval Service), NAVMC 78-PD (U.S. Marine Corps Report of Separation), and NAVCG-553 (Notice of Separation from U.S. Coast Guard) (VA, 2023).

the Army Dosimetry Center, which responded that its program was initiated in 1954 and does not have records from the Manhattan Project.14

U.S. Army Center of Military History

CMH has the goal of preserving and disseminating history for both Army training and to educate the public and provide historical advice to Army staff. CMH also performs museum management for a vast network of Army museums and historical holdings, conducts extensive historical research, maintains official records and lineage information for all Army units, preserves oral histories, and maintains data-retrieval systems (CMH, n.d.). Army historians maintain the organizational history of Army units, allowing CMH to provide units of the Regular Army, Army National Guard, and Army Reserve with certificates of their lineage and honors and other historic material. CMH also determines the official designations for Army units and works with Army staff during force reorganizations to preserve units with significant histories, as well as unit properties and related historic artifacts.

Army Regulation 870-5 (U.S. Army, 2007) requires historical data from reporting agencies within the Army Secretariat be submitted to CMH for inclusion in and updates to the Annual Department of the Army Historical Summary not later than 120 days after the end of the fiscal year being reported. It also states that

The lineage of an organization establishes the continuity of the unit despite various changes in designation or status, thereby certifying its entitlement to honors, as well as heraldic items, organizational historical property, organizational history files, and other tangible assets. Each lineage entry is supported by substantial proof, normally documentary in nature. (U.S. Army, 2007, p.13)

Based on the mission of CMH, it appears that it could assist in completely quantifying authorized troop strength. An information request was sent to both Charles Bowery, the executive director and chief of military history, and Stephen J. Lofgren, director of CMH’s Field Programs and Historical Services Directorate. CMH was initially responsive and had a preliminary call with National Academies staff in which it indicated that a search of its holdings for information pertinent to the units that served in the Manhattan Project had identified a few items to share but in general “we do not have much to offer directly for this effort.”15 The request for

___________________

14 Personal communication, William S. Harris, chief, U.S. Army Dosimetry Center, February 26, 2024.

15 Personal communication, Stephen J. Lofgren, director, Center of Military History’s Field Programs and Historical Services Directorate, February 29, 2024.

information included five inquiries regarding the contents of specific collections listed on the CMH website and publicly available finding aids:

- Willis, Samuel A. Box 24 T/4 9812 Tech Serv Unit Survey, discharge;16

- Characterization or description of records and quantitative and/or qualitative data held by the Army (or DoD) which document activities of active-duty military personnel of any rank and role, assigned to the Manhattan Project, at any location, from January 1, 1942, to August 31, 1947, including names, job titles, and specific locations of duty stations;

- Whether CMH has records that contain radiation or chemical exposures;

- Records that contain health outcome information for service members who served anytime in 1942–1947 regardless of when the health outcome occurred; and

- Locations and process to access such records.

CMH further declined to give a presentation to the committee but stated that it would send written responses to the committee’s questions. However, despite numerous follow-up e-mails over 12 months, no written responses or other source items were ever provided.

Department of Veterans Affairs

The committee began its work with a January 10, 2024, presentation by VA’s sponsoring office, Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Health Outcomes Military Exposures (HOME), which included discussion between VA and the committee regarding the bounds of its statement of task (see Chapter 2). In addition to this presentation, the committee sent specific information requests to the HOME office and, via this office, to the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA). A separate request was sent to the office of the VA chief historian. VA does not keep any medical records from the relevant period and added that all records of veterans serving during that time have been transferred to NARA’s Research Services or are in the life cycle process at NARA’s Federal Records Center. Archivists within the VA Office of History searched VA and HOME’s archival collections and found that the latter contains information only from the Vietnam era onward.17 In sum, the committee determined that VA does not maintain complete rosters of veterans who served in military

___________________

16 Army Heritage, 2009; this has since been removed.

17 Personal communication, Michael D. Visconage, chief historian, Department of Veterans Affairs, February 9, 2024.

units over the entire course of any conflict or for the Manhattan Project, nor does it intend to create one.

Within the VBA administrative databases, no identifier for the Manhattan Project exists or indicator to facilitate locating such records. VBA does have the ability to request claims data for veterans by period of service, and specifically World War II (1941–1946), but it has no identifier or indicator that would allow it to search or stratify those records by a site of interest. VBA noted 11,448 total compensation claims for all World War II–era veterans as of September 30, 2023, but with no master roster of Manhattan Project veterans, VBA is unable to determine how many of them submitted a claim for compensation.18 Within the response to the committee, VBA included PDFs of the full annual reports for each year 1942–1947 that contain numbers of living and deceased veterans by conflict era and aggregated benefits and health data. Each report is about 150 pages and contains a section of aggregated tables of medical treatment, but individuals or units are not specified.18 VA operates several databases with veteran information, including Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem, VHA, and VBA, that might be used to identify or confirm veteran status. These are covered in more detail in Chapter 6.

Non-Military Sources of Records

Technical SED and PED personnel may have continued to be employed by DOE when their work on the Manhattan Project was finished; however, the committee was unable to estimate how many might have done so. Therefore, it is only those who worked for DOE (or its predecessor agencies) whose records would be kept by DOE site records managers. The DOE Office of Science and Technical Information houses a large, digitized database of historical information and is supported by the Office of Classification. One source of documentation might be DOE’s OpenNet online database (DOE, n.d.b). Some information pertaining to radiological exposures among Manhattan Project personnel has been collected through the now closed DOE Office of Human Radiation Experiments,19 last updated in 2012, but most of it is related to people that would be excluded from this feasibility assessment, given the timing and types of exposure.

However, this section presents the general structure of DOE offices that are responsible for records and summarizes what was learned through

___________________

18 Personal communication, Carla Ryan, assistant director, Military Exposures Team, Department of Veterans Affairs, September 17, 2024.

19 Information from the Office of Human Radiation Experiments remains accessible through the website. The website also lists by site the available archives and record holdings (Office of Environment, Health, Safety and Security, n.d.).

information-gathering sessions near the primary sites of Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos. After describing these DOE sources, other sources are described, including lists of veterans compiled by researchers, OARU, the Atomic Heritage Foundation, and others.

Department of Energy Records Managers

DOE records management of Manhattan Project–era sites is split between the Records Management Office, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), and the Office of Legacy Management, which maintain these records through the various field offices at those sites. Due to the complexity of records ownership among DOE offices, no single point of contact exists to identify records at each site for this feasibility assessment. Within the Office of Records Management, field offices maintain site-specific records. For example, the DOE Office of Science, DOE Environmental Management office, and NNSA maintain records for Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos, respectively.

Records for sites that have been closed are maintained by the Office of Legacy Management, including for Uravan and Lake Ontario Ordnance Works. The Office of Legacy Management, in partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, runs the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program, for which it maintains historical records at its Business Center storage facility in Morgantown, West Virginia. This storage facility holds 70,000 cubic feet of physical records and more than 4 million digital items (Office of Legacy Management, n.d.). This collection contains records of Manhattan Project and U.S. Atomic Energy Commission work contracted to private and academic entities. For many of the sites, it has the only remaining record of that work. Without responses by the Office of Legacy Management to the committee’s request for information (see Chapter 2), many unknowns affect the committee’s ability to offer a more complete assessment of available data for a study.

For those records verified to be under the aegis of DOE, the first step is to make a formal request to DOE Records Management Headquarters to be given a contact and introduction to the appropriate field office. The committee took this approach for each of its information-gathering sessions at the three primary Manhattan Project sites and required multiple coordination and approval requests before information was provided. Approvals for this congressionally required effort took on average 6–8 weeks. The committee appreciates and acknowledges the in-kind time that the site records managers spent in responding to its requests, preparing for and presenting to it during site-focused information-gathering sessions, and responding to follow-up questions and clarifications in support of this feasibility assessment. Should additional effort be needed to find and retrieve records for a

study, a cost may be associated with records retrieval or use of some of the databases discussed in the following sections.

Records at Oak Ridge

Records Management directed the committee to the Office of Science, Consolidated Service Center in Oak Ridge, which manages the DOE’s employment records. To request a document from here, one must go to their website and fill out a digital request form and provide as much detailed information as possible, such as document number, title, date, and author if known. However, many documents “are no longer available to the public due to new security criteria enacted after September 2001” (DOE, n.d.a). When a request is made, it is subject to security review by the office.

Jennifer G. Hamilton, senior program analyst for the Records, Directives, Technical Standards Programs, and the Science Management System, at the Office of Science Consolidated Service Center in Oak Ridge, responded to National Academies staff inquiries about what applicable 1942–1947 information is available, such as names, job titles or categories, rank, or other indication of military service, and locations of service. Her presentation to the committee at its third information-gathering session described the potential data that could be found in Oak Ridge employment records and estimated the labor associated with reviewing and abstracting it. She included images of examples of types of records, such as a workman’s compensation case card from 1944–1948 and an employee termination card dated 1945, but all information on these records was redacted (Hamilton, 2024). Furthermore, she reviewed a random sampling of 250 employee cards identified as likely to have military information; of these cards, 15 (or 6%) had rank beside the name, indicating military service. She stated that approximately 246,000 employment cards are at the Oak Ridge Consolidated Service Center Records Management Library, and to review all of these would take approximately 984 hours, or 6 months of full-time work by one person. However, it cannot be assumed that the estimated 6% identified as military based on one sample is representative of all employment records. This estimate is based on hand review and not potential use of more automatic artificial intelligence and character recognition processes. Any information about former employees that would be used for research and so would be made public would need to first be shared with and reviewed by the Consolidated Service Center Privacy Act Officer and their Oversight Attorney. Consistent with protections for personally identifiable information, Social Security numbers or other personal

employee information needed by researchers would require a derivative classifier before release.20

In addition to hearing from records management at Oak Ridge, local historians and museum directors associated with the Y-12 National Security Complex and the K-25 gaseous diffusion process building at Oak Ridge were contacted about presenting to the committee on military presence during the Manhattan Project and records availability. Most did not respond, and the two that did declined to present. The records office of Methodist Medical Center in Oak Ridge was also contacted to request information on records for 1943–1947 because it was the former Oak Ridge Army Hospital, which began operating in November 1943. The records office staff stated that the hospital does not keep records from that period, and they were unaware of where the records may have been moved or if they were destroyed.21

Records at Hanford

At the fifth information-gathering session, in Richland, Washington (near Hanford), Meg Milligan, records management field officer at the Richland Operations/Office of River Protection, and Lorna Zaback, Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act (EEOICPA) Workers Compensation Program Management and program analyst at the Hanford Workforce Engagement Center, gave an overview of their offices’ records and the potential use of them for a study of Manhattan Project service members. Records managers indicated that some of the records that may be useful in identifying military personnel at Hanford, including locator cards for personnel, phone books with lists of individuals with rank notes next to names, employment files, work history reports, a security database, dosimetry records and accident reports, organizational charts, and union cards. Other files at Hanford include temporary badges for visitors, which may indicate military service, a personnel badge book, personal records of Manhattan Project worker family members, and monthly unit reports, but it is unknown what information these sources may provide. Additionally, the records management office has some mimeographs and magnetic tapes of “daily attendance sheets” for which digitization is planned but not yet started (Milligan and Zaback, 2024).

Many of the examples of records provided were prepared for EEOICPA and have been digitized, but these records did not differentiate between

___________________

20 Personal communication, Jennifer G. Hamilton, senior program analyst, Office of Science Lead Records Management Field Official, Office of Science Consolidated Service Center, June 17, 2024.

21 Personal communication, Methodist Medical Center Staff, April 22, 2024.

military and non-military personnel. The records managers said that any record that identified a specific person at a specific location or in a specific job was digitized and data mined for EEOICPA. They believe that they might be able to identify military status through classified badge data, but these data may only go back to 1965. Exposure records at Hanford through 1946 were taken to DuPont’s headquarters in Wilmington, Delaware, and their disposition is unknown. The Hanford site records management office could be used as a supplementary source to confirm locations of individuals added to a roster created from National Archives at St. Louis records, but it could not be a primary source for identifying those Manhattan Project military personnel assigned to Hanford due to the comingling of civilian and military records and lack of rank in many unclassified records.