Evaluation of Manhattan Project Records for Veteran Health and Exposure Assessments (2025)

Chapter: 3 Locations Specified in the Statement of Task and Other Manhattan Project Military Sites

3

Locations Specified in the Statement of Task and Other Manhattan Project Military Sites

The Manhattan Project was a large-scale, top-secret undertaking that employed an estimated 500,000–600,000 individuals who worked in a variety of capacities at three main sites: Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Hanford, Washington; and Los Alamos, New Mexico. On August 13, 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers assumed direction of the Manhattan Project and established the Manhattan Engineer District (MED) to manage this vast undertaking. Some historians have estimated that more than 200 separate sites (including research and academic institutions, military and government institutions, and private companies and contractors) were located across the United States (Wellerstein, 2019). Thousands of contract workers and military service members built, maintained, and worked at these sites during the Manhattan Project. In January 1947, President Harry S Truman began the transfer of the Manhattan Project plants, laboratories, equipment, and personnel to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). This transfer included 37 installations, 254 military officers, 1,688 enlisted men, 3,950 government workers, and about 37,800 contractor esmployees (Hewlitt and Anderson, 1962).

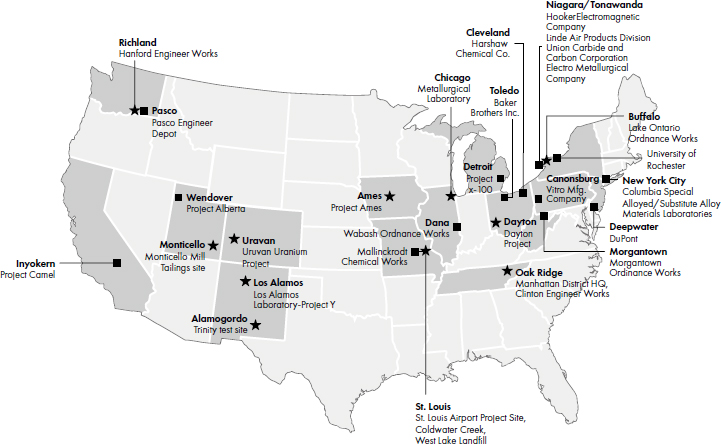

Figure 3-1 shows a continental map of the United States and select Manhattan Project sites, noting whether they were named in the statement of task. The specified 13 sites include the three main sites, three sites in St. Louis County, Missouri (Coldwater Creek, St. Louis Airport Project Site, and West Lake Landfill); Alamogordo, New Mexico (until July 16, 1945); the Lake Ontario Ordnance Works (LOOW) in Buffalo, New York; the University of Chicago (Metallurgical Laboratory (Met Lab)), Illinois; the Ames Project at Iowa State College (now Iowa State University), Ames, Iowa; the

NOTE: Stars designate Manhattan Project sites specified in the statement of task; squares designate other Manhattan Project sites of note.

SOURCE: Locations added by committee; map of the U.S. adapted from Wikimedia Commons, 2011. CC-BY SA 3.0.

Dayton Project in Dayton, Ohio; Monticello, Utah; and Uravan, Colorado. It is acknowledged that these sites existed within an intricate network of an estimated 200 Manhattan Project sites overall, only a selection of which are noted on the map.

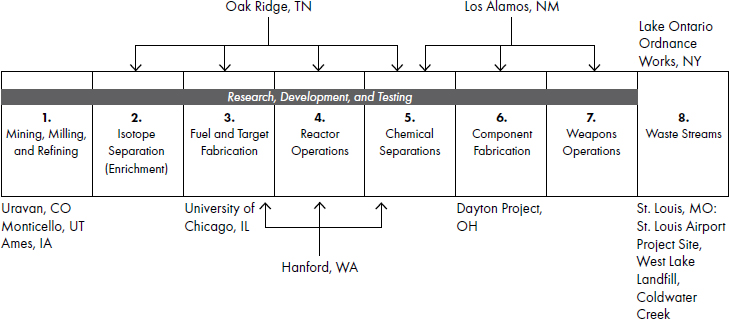

Manhattan Project activities and processes included large-scale production; research; waste management; component fabrication (including chemical processing for recovery, purification, and recycling of plutonium, uranium, and other metals, and component production scrap and residues) (DOE, 1997); uranium mining, milling, and refining; and testing. Figure 3-2 shows the general types of activities and how each of the sites in the statement of task fit into the complex process of nuclear weapons development. The Manhattan Project involved numerous heterogeneous chemical and radiological hazards, and each step of the manufacturing process represented an opportunity for exposure to multiple radiological and chemical hazards.

After the end of World War II and the conclusion of the work of the Manhattan Project, its many sites changed administrative hands, from one or more contractors to others, with some sites doing so multiple times. Handwritten and typed records documenting the wartime work, which

NOTES: Alamogordo, New Mexico, does not appear in this figure as the primary purpose of the site was for the Trinity test. Several of the processes occurred concurrently as indicated in part by the multiple arrows.

SOURCE: Adapted from Department of Energy (1997).

may have included lists of civilian and military staff, were often destroyed. If not, they were archived in various locations, fragmenting the historical record of the work and making future studies, such as this feasibility study, a challenging prospect.

This chapter describes the work that took place at the 13 Manhattan Project sites listed in the statement of task; other Manhattan Project sites are also discussed if they have evidence of a military presence. Unless otherwise noted, the discussion in this chapter pertains to those 13 sites. The sites are grouped by the type of work performed between 1942 and 1947. For each site, the following aspects are described: Manhattan Project activities conducted; likely sources of exposures and waste generated by those activities; documented active-duty military presence including numbers when available; and any epidemiologic studies of workers, since no epidemiologic studies specifically of service members or veterans were identified. The chapter begins with the three primary sites (Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos), which performed multiple roles for the project and had the largest number of service members. The sections that follow describe the research laboratories (University of Chicago and Iowa State), mining and milling sites (Uravan and Monticello), component fabrication (Dayton Project), and waste storage sites (St. Louis Airport Project Site, Coldwater Creek, West Lake Landfill, and the Lake Ontario Ordnance Works). After descriptions of these sites, other Manhattan Project sites that were not included in

the statement of task but may offer additional insights or information are briefly discussed.

Epidemiologic studies of workers or residents at or around Lake Ontario Ordnance Works in Buffalo, New York; the University of Chicago Met Lab in Chicago, Illinois; the Ames Laboratory at Iowa State, Ames, Iowa; and the vanadium mine located near Monticello, Utah, were not identified by the committee’s literature search. Epidemiologic investigations were also conducted at some facilities that performed work similar to the Manhattan Project in later years, such as Rocky Flats, Colorado, and Fernald Feed Materials Production Center, Ohio (Milder et al., 2024a). These sites or studies of workers at them are not summarized, as they were not included in the statement of task, but they are mentioned because investigators may find them informative regarding health outcomes of exposures similar to those of Manhattan Project veterans.

SELECTIVE HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE MANHATTAN PROJECT SITES

Despite dozens of historical books about the Manhattan Project overall—documenting its origins, challenges, development, achievements, and legacies—site-specific professional histories are relatively few. The three primary production sites have received the greatest attention from professional historians. Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project (Hales, 1999) examines all three primary sites (Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos).

Site-specific historical studies of Oak Ridge include At Work in the Atomic City: A Labor and Social History of Oak Ridge (Olwell, 2004); City Behind a Fence: Oak Ridge, Tennessee (Johnson and Jackson, 1981); Oak Ridge National Laboratory: First Fifty Years (Johnson and Schaffer, 1994); and The Girls of the Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II (Kiernan, 2014). Historical studies of Hanford include Atomic Frontier Days: Hanford and the American West (Findlay and Hevly, 2011); Nowhere to Remember: Hanford, White Bluffs, and Richland to 1943 (Bauman and Franklin, 2018); Made in Hanford: The Bomb that Changed the World (Williams, 2011); and Supplying the Nuclear Arsenal: American Production Reactors, 1942-1992 (Carlisle and Zenzen, 1996). Los Alamos is documented in Inventing Los Alamos: The Growth of an Atomic Community (Hunner, 2007).

Of the many other Manhattan Project sites across the United States, only a handful have received comparable attention. Historical books about them include Nuked: Echoes of the Hiroshima Bombs in St. Louis (Morice, 2022); Polonium in the Playhouse: The Manhattan Project’s Secret Chemistry Work in Dayton, Ohio (Thomas, 2017); Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic

Bomb (Jones, 1985); and the three-volume series The New World, 1939–1946 (Hewlett and Anderson, 1962), Atomic Shield, 1947–1952 (Hewlett and Duncan, 1969), and Atoms for Peace and War, 1953–1961: Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission (Hewlett and Holl, 1989).

PRIMARY MANHATTAN PROJECT SITES

The large-scale nuclear production facilities at Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos operated in tandem to produce the materials necessary for the world’s first nuclear weapon. Oak Ridge was the site of uranium enrichment, a process that increased the concentration of the fissile uranium-235 isotope. It also housed the X-10 graphite reactor, which produced small amounts of plutonium. Hanford was dedicated to plutonium production; massive nuclear reactors generated plutonium-239. The enriched uranium and plutonium from these two large facilities were then transported to Los Alamos, where both the implosion-type plutonium weapon and the gun-type uranium weapon were designed and constructed. Military personnel were at each of these sites, and thus, potentially exposed to a wide range of hazardous materials, including radioactive isotopes and other chemical substances.

Oak Ridge, Tennessee

In 1942, General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., approved creating a uranium enrichment and separation site in Eastern Tennessee on 59,000 acres called the Clinton Engineer Works, later renamed Oak Ridge (Oak Ridge Convention and Visitor Bureau, 2024). The site encompassed multiple facilities, including two uranium enrichment plants (K-25 and Y-12), a liquid thermal diffusion plant (S-50), and a laboratory and graphite pile reactor (X-10). Operations for the Y-12 plant were overseen by the Tennessee Eastman Corporation, a former methanol and cellulose acetate yarn production company that had a contract with the U.S. Army Ordnance and National Defense Research Committee to manufacture explosives during World War II (Egan, 2018).

The X-10 Graphite Reactor, built by DuPont de Nemours, Inc. (DuPont), included aluminum cans holding uranium slugs that would drop into the first cell of the chemical separation facility, dissolve, and begin the plutonium extraction process. The facility prioritized plutonium production until 1945, when Hanford assumed responsibility (ATSDR, n.d.). In 1944, a pilot plant located alongside the X-10 graphite reactor used the bismuth phosphate process for extracting plutonium from irradiated uranium (DOE, 1997). The X-10 site produced radioactive lanthanum between 1944 and 1956; during processing, the by-product radioactive iodine was released

into the air via stacks and vents (Apostoaei et al., 1999). It also housed the solid waste burial ground starting in 1944.

The S-50, K-25, and Y-12 facilities at Oak Ridge used separation methods to enrich natural uranium with uranium-235 (U-235), the isotope relevant to producing a nuclear weapon, from the more common uranium-238 (U-238) isotope, each using a different mass separation method. The three facilities were designed to operate simultaneously, each stage increasing the concentration of U-235 (NPS, 2023c). The uranium product was enriched at S-50 (up to 0.9% U-235), and this was fed into the K-25 plant, which used the gaseous diffusion method to separate the isotopes of U-235 from U-238. That process raised the enrichment to about 20%. This was fed into the Y-12 plant for the final enrichment cycle (up to 90% U-235) (NPS, 2023c) using electromagnetic separation. The enriched uranium and plutonium were transported to Los Alamos for further development into nuclear weapons. Release of ionizing radiation, uranium, hydrogen fluoride, and fluoride resulted in potential exposures for workers on the K-25 and S-50 sites in particular (ATSDR, 2012). The S-50 plant ceased operations in 1945, and Y-12 ceased uranium enrichment in May 1947 and became a nuclear materials fabrication operation (DOE, 1997).

The Navy’s contributions, although small in terms of personnel, played major roles in the ultimate success of the Manhattan Project as a result of research conducted by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory at Anacostia Naval Air Station and the Philadelphia Navy Yard at pilot plants to test the feasibility of the liquid thermal diffusion process to produce enriched uranium. The process evolved into the operations of the S-50 thermal diffusion process building.

At Oak Ridge, tens of thousands of laborers, contractors, and Army Special Engineer Detachment (SED) personnel were tasked with constructing the production plant and the town that housed the scientists and operating personnel (Hewlitt and Anderson, 1962). The majority of workers were White, but approximately 7,000 African Americans contributed to the war effort at Oak Ridge, but they were segregated (NPS, 2023g); no documentation was found for African Americans being assigned to Manhattan Project military units. While the site was mostly occupied by civilians, there are records of military police, SED members,1 and Women’s Army Corps (WAC) personnel (OSTI, n.d.g). Military police guarded technical and restricted areas, 62–190 soldiers were usually assigned to the site at any time (OSTI, n.d.g). SED personnel peaked at 450 at Y-12, 500 at K-25, 126

___________________

1 Army Corps of Engineers officers were engineers who oversaw the construction of the plants and community site at Oak Ridge. SEDs were involved in the scientific and technical aspects and operations of the production plants at Oak Ridge.

at S-50, and 100 at X-10, but no years were given for when these peaks occurred (OSTI, n.d.h). A separate WAC detachment was established on June 3, 1944, with an initial 74 women split among Hanford, Los Alamos, and Oak Ridge. The WAC Yearbook on the Atomic Heritage Foundation website lists 422 WAC members working on the Manhattan Project (U.S. Army, 1946b). They were stenographers, typists, clerks, librarians, cooks, drivers, hospital technicians, scientific research staff, and telephone operators. They handled both classified and nonclassified records, reports, files and communications. Some became metallurgy, electronic, or spectroscopic technicians (McGehee, 2004; U.S. Army, 1946b).

Numerous health studies have examined morbidity and mortality among Oak Ridge workers from the 1940s to the present day. The types of radiation exposures and radiation monitoring programs differed and changed over time for each Oak Ridge facility (Frome et al., 1997). The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) has a collection of reports detailing various exposures and health outcomes associated with the different facilities from the Manhattan Project. None of the ATSDR reports specifically refer to military populations, but it is likely that veterans who were at Oak Ridge were included in cohort studies of the entire workforces.

Among the studies of workers at Oak Ridge (Checkoway et al., 1985; Wing et al., 1991, 1993), of particular relevance is a large cohort study of 106,020 workers employed at any of the four facilities (K-25, Y-12, S-50, X-10) between 1943 and 1985 (Frome et al., 1997). It compared mortality among workers at the four facilities and conducted dose–response analyses for those potentially exposed to external radiation. It also addressed methodologic challenges associated with analyzing data for individuals who worked at more than one plant. Annual external dose estimates were computed for workers obtained from a postwar computerized database of personal monitoring data collected by each facility as part of its radiation monitoring program (Watkins et al., 1997). Internal radiation exposure was also obtained from that database (computerized during the Cold War era) and categorized for analysis as eligible for monitoring but not monitored, eligible for monitoring and monitored, or not eligible for monitoring. Vital status was obtained from the Social Security Administration (SSA). The number of military veterans included in the cohort or what proportion of the cohort was working during 1942–1947 is not stated. The authors reported that all-cause mortality and all-cancer mortality were similar to national rates. Among White men, an excess of lung cancer (standardized mortality ratio (SMR) = 1.18) and nonmalignant respiratory disease (SMR = 1.12) was observed, but no confidence intervals were provided. In analyses of external radiation doses in a subcohort of individuals who worked at X-10 or Y-12 (n = 28,347), the excess relative risk (ERR)

at 10 millisievert2 (mSv) for all cancers (ERR = 1.45; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.15–3.48) and lung cancer (ERR = 1.68; 95%CI 0.03–4.94) were both elevated.

In another occupational cohort mortality study, Richardson and Wing (1999) examined 14,095 workers employed at X-10 between 1943 and 1972. The study population included White and non-White males and females; some had also been employed at other Department of Energy (DOE) facilities (Y-12, K-25, Hanford, and Savannah River). Similar to Frome et al. (1997), there was no indication of whether military veterans were included in the cohort and, if so, how many or what proportion of the cohort was working during 1942–1947. Vital status was determined through SSA records, National Death Index (NDI) data, and employer information through 1990. External radiation exposure was obtained from Oak Ridge National Laboratory personal monitoring records that started in February 1943 to determine cumulative radiation dose. Notably, while radiation exposure monitoring began in 1943, and by 1948 over 98% of workers were monitored, it was not standard procedure for employees to have a dosimeter until November 1951. Exposures other than external ionizing radiation may have occurred, but limited quantitative data were available regarding individual exposures to agents such as beryllium, lead, or mercury. The authors used 5-, 10-, and 20-year lagged cumulative external radiation doses after age 45 years in regression models adjusted for age, race, sex, birth cohort, employment status, pay code, and internal radionuclide monitoring to examine associations with mortality from multiple causes. The lagged exposures were associated with increased mortality from all cancers (percent increase per 10 mSv of dose = 4.39%, 4.98%, and 7.31% for 5-, 10-, and 20-year lags, respectively), lung cancer (percent increase per 10 mSv = 5.19%, 5.48%, 6.63%), and all cancers except lung (percent increase per 10 mSv = 3.88%, 4.67%, and 7.69%).

Hanford, Washington

In 1943, the U.S. government selected and sequestered a 586-square-mile area at Hanford for a new plant that used uranium to produce plutonium with a nuclear reactor. Nearly two-thirds of the plutonium in the Trinity test and the nuclear weapons used by the U.S. military in World War II was produced at Hanford Engineer Works (DOE, 2024).

Collaboration between the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and DuPont resulted in constructing three production areas: 100, 200, and 300. Area 100 housed the three water-cooled production reactors (piles) B, D, and F. The main function of the massive chemical separation plants in the 200 Area was to remove plutonium from uranium fuel rods (DOE, 2021). The largest

___________________

2 The unit of effective dose is J/kg, with the special name sievert (Sv) (ICRP, 2007).

such facility was the T Plant, which began operating in 1944 to separate the plutonium from the uranium and other radioactive by-products of irradiation (AHF, 2022d; NPS, 2023d). The facility incorporated ventilation systems for low-concentration release of certain gaseous chemicals, notably iodine-131, and waste storage tanks. A second, smaller facility, the B Plant, performed the same separation functions and began operating in 1945. Both plants used the bismuth phosphate process (DOE, 1997). Area 300, 20 miles south of the chemical separation plants near Richland, Washington, produced uranium slugs for fueling the reactors and housed a small 50-watt graphite pile and a technical laboratory for experiments of more efficient means to transform uranium into plutonium (DOE, n.d.c; OSTI, n.d.e).

The first step in the transformation process was to create fuel slugs by forming uranium rods, then confining the slugs in aluminum “cans.” Nearly 20 million uranium fuel slugs were prepared at Hanford (Gephart, 2003). The first slugs were loaded into the B Reactor on September 13, 1944. Through nuclear reactions, a portion of the U-238 was converted to plutonium-239. The B Reactor reached full operation in February 1945, and its operations continued until it was shut down at the end of 1946. However, it was restarted in 1948 to support plutonium production for the Cold War and operated through 1967. It was shut down permanently on February 12, 1968 (DOE, n.d.a).

The canned slugs, at this point highly radioactive and thermally hot, were pushed through the reactor and out the back into water-filled storage tanks for a cooling period of approximately 2 months before being transported to the T or B plants (Gephart, 2003; OSTI, n.d.a). These storage tanks were diluted with water from the adjacent Columbia River, and radioactivity levels were monitored until they were at an acceptably low level (not defined) before release (Gephart, 2003; OSTI, n.d.a).

As a result of these chemical and nuclear processes, Hanford produced large quantities of both solid and liquid waste. Since 1944, it has released at least 142 million curies3 of radioactivity into the air, soil, and Columbia River (Richards, 2016). On site, 56 million gallons of radioactive and chemical waste were placed into 177 underground storage tanks (DOE, 2016). After environmental contamination concerns, Hanford became the concentration of the nation’s largest environmental cleanup, which is ongoing at an estimated cost of $2.8 billion annually (DOE, 2024; NASEM, 2022; NRC, 1996).

Hanford required a large workforce to perform the highly sensitive and complex work of plutonium production and maintain the numerous

___________________

3 A curie is a non-International System of Units measure of radioactivity and represents the number of decays per second of a radioisotope. A standard smoke detector contains 0.9 microcuries. The overall radioactivity is roughly equivalent to 161 trillion smoke detectors.

facilities. Contracted construction peaked at 42,400 workers in June 1944, and the site housed approximately 50,000 people at its peak in 1944, with an additional 17,500 people living in the nearby community of Richland (OSTI, n.d.b). According to DOE, DuPont hired 94,307 construction workers, with approximately 45,000 at the peak in May 1944 (Harvey, 2000). The majority were White; approximately 15,000 African Americans contributed, but they were segregated (NPS, 2023e). Military presence at Hanford seems to have been primarily the Army Corps of Engineers construction teams that, in collaboration with DuPont, built the production facilities. MED, through the War Manpower Commission, recruited large numbers of civilian workers to Hanford in collaboration with DuPont representatives stationed at recruiting centers around the country (OSTI, n.d.f).

According to the Hanford Site Historic District, 175 military personnel were assigned to Hanford on September 28, 1944, and December 31, 1944. The number increased in 1945 to 224 by March 31 and 268 by June 30 and then decreased to 225 on September 30, with a final rise to 243 by December 31. The next year, the numbers of military personnel fluctuated as well, with 316 by March 31, 259 by June 30, 290 by September 30, and 270 on December 31, 1946. In 1947, the numbers rapidly dropped off as the AEC assumed oversight of the complex; military personnel declined from 262 in March, to 12 in June, and to 3 in September (Cannan, 2001). The numbers in this source do not indicate to what group these military personnel were assigned, that is, whether they were SED, WACs, military police, or any other group.

As secrecy of the Manhattan Project goals remained imperative to military and government leadership, military police were assigned to escort classified material moved within and out of Hanford (Harvey, 2000). Transporting the purified plutonium to Los Alamos, New Mexico, was predominantly by military ambulance and caravan to avoid suspicion. It was performed in secret and likely by military units similar to those transporting material within Hanford. The first small shipments of plutonium from the Hanford 200 area reached Los Alamos on February 2, 1945, with larger quantities transported through May 1945 (OSTI, n.d.b).

Several epidemiologic studies have investigated the health of workers and community members living near the Hanford site, including studies related to exposures to plutonium (Wing et al., 2004; Wing and Richardson, 2005) and iodine-131 (CDC, 2009; Davis et al., 2002). Although these studies did not specifically investigate outcomes in veteran populations, they provide relevant background to help the committee consider the types of exposures at Hanford and potential health outcomes.

In a cohort mortality study, Wing et al. (2004) examined health outcomes related to plutonium exposure in 26,389 workers hired 1944–1978, with no indication of the number of veterans included or what proportion

of the cohort was working 1942–1947. Vital statuses for 1944–1994 were obtained from linkage with SSA records, Health Care Financing Agency records, NDI, and driver’s license records from Washington state. Plutonium exposure potential was determined by creating a job-exposure matrix using 1944–1989 employment files. The highest rates of bioassay-confirmed plutonium deposition were in workers who had been employed for 5 or more years in jobs with routine plutonium exposure potential and who had never held non-routine plutonium exposure jobs. Depending on their job, workers also may have been exposed to various chemicals and radionuclides (see Chapter 5). Compared with workers who had no employment in routine plutonium jobs (0 years), workers with more than 10 years of such employment had increased annual death rates for non-external causes (defined as International Classification of Disease 9th Revision codes 001–799), cancers of tissues where plutonium deposits occur (defined as a composite outcome of lung, liver, bone and connective tissue, and lymphatic tissue cancers), and lung cancer of 14.2%, 6.9%, and 20.4%, respectively. When stratified by age, these positive associations were found only in those workers aged 50 years or older (Wing and Richardson, 2005).

Los Alamos, New Mexico

In January 1943, Project Y was established at Los Alamos to develop, design, and test nuclear weapons. The operations were carried out by a partnership between the University of California, where Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer was employed, and the Army Corps of Engineers with Colonel John M. Harman as the first commanding officer. The initial survey conducted by Army engineers proposed an acquisition of 54,000 acres for the Los Alamos site (OSTI, n.d.m) that became home to more than 6,000 scientists, engineers, technicians, and military and support personnel (NPS, 2024).

Exposure to plutonium and enriched uranium and other hazardous materials, such as beryllium, was highly probable for those inside the technical area, where the uranium gun type and the plutonium-core implosion–type nuclear weapon were developed and constructed. While military personnel were tasked with transporting radioactive materials between Los Alamos and Alamogordo for the Trinity test, much of the radioactivity was shielded and would have resulted in minimal exposure to those handling the radioactive core (Hacker, 1987). See Chapter 5 for additional discussion of potential exposures.

Military personnel assigned to Los Alamos included military police, those in the Provisional Engineer Detachment (PED), a detachment of WACs, and technical personnel in SED. The military police manned guard posts 24 hours a day (OSTI, n.d.g). In 1942, the military police contingent

was 7 officers and 196 enlisted men; by December 1946, it was 9 officers and 486 enlisted men (OSTI, n.d.g). PED personnel performed maintenance of buildings, roads, and facilities onsite and consisted of 465 men through June 1946 (AHF, 2017b; Truslow, 1973). WACs performed a wide variety of jobs, including transportation, telephone operation, clerical tasks, hospital technicians, and some specialized scientific research within the technical area (OSTI, n.d.f). The WAC detachment initially had 2 officers and 43 enlisted women and reached a peak of approximately 260 women in 1945 (OSTI, n.d.d). SED service members “worked on everything from bomb design to inventory control, often in tandem with their civilian counterparts” (AHF, 2022f) and by 1945 included over 1,800 men. Most military units lived apart from the civilian population, apart from Navy officers who were categorized in the same way as scientific personnel, and some Army officers who brought their families to site and were afforded family housing privileges (U.S. Army, 1946d).

By 1945, 41 Navy officers with technical qualifications were assigned to Los Alamos (Cox, 2020). Several of them were renowned scientists when they accepted their commissions in the U.S. Navy Reserve (Cox, 2020). Navy personnel were few compared to those from the Army SED, WAC, PED, and military police at the site.

Numerous epidemiologic studies have examined potential associations between occupational exposures at Los Alamos and a variety of health outcomes (Daniels et al., 2006; Galke et al., 1992; Hempelmann et al., 1973; Voelz et al., 1997; Wiggs, 1987, 1994; Wilkinson et al., 1987). Most recently, a 2021 cohort mortality study of 26,328 workers included men and women employed at Los Alamos (what would become Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in 1981) anytime 1943–1977 and those employed by the ZIA Company, a support services contractor to LANL, anytime 1946–1977 (Boice et al., 2021). The LANL study included 8,368 workers hired 1943–1949; however, it is unknown how many or which of them were veterans or how many worked specifically 1942–1947. The authors note that they obtained radiation exposure dosimetry for 301, 138, and 19 workers who had ever served in the Navy, Air Force, and Army, respectively, during the study follow-up, but it is unknown if any of those linkages pertain to service 1942–1947. Vital status was obtained through December 31, 2017, using NDI, state mortality files, the SSA Death Master File, SSA Service to Epidemiological Researchers, and credit reporting agencies. Gamma, neutron, and tritium exposures obtained during previous studies of these workers were used to calculate estimates of external radiation to different body tissues. Bioassay data and incident reports from LANL were used to estimate potential intake of plutonium-238 and plutonium-239. Observed numbers of deaths were compared to expected numbers using SMRs. Cox proportional hazard models were used to conduct internal cohort analyses

to calculate risk across different categories of estimated doses of radiation to specific organs and tissues. Compared with the general U.S. population, an excess of berylliosis was observed but based on only four deaths. Increased mortality for bone cancer was observed among workers monitored for plutonium exposure based on seven cases (SMR = 2.44; 95%CI 0.98–5.03) but not among those not monitored for plutonium (n = 4 cases, SMR = 0.63; 95%CI 0.20–1.48). The analysis also identified a statistically higher than expected number of suicides among exposed workers (n = 309, ERR = 1.16; 95%CI 1.03–1.30), particularly women (n = 49, SMR = 1.92, p < 0.05). In internal cohort dose–response analyses, an increased risk was observed for esophageal cancer (n = 106; hazard ratio (HR) at 100 mGy = 1.33; 95%CI 1.02–1.73). Notably, this and past studies of the LANL workforce have included military veterans but not conducted analyses limited to them. However, these larger occupational studies offer insight into the types of methods and procedures needed to find and assess exposure and health data for 1942–1947.

Alamogordo, New Mexico

Although Alamogordo was added to the list of Manhattan Project sites in the statement of task, VA told the committee during its official charge that atmospheric and nuclear weapons testing was out of its scope. This excludes Alamogordo after the Trinity test (after July 15, 1945). However, the committee discusses Alamogordo in the context that many service members from Los Alamos constructed the Trinity test site and witnessed the detonation (U.S. Army, n.d.).

Manhattan Project leaders selected a site 210 miles south of Los Alamos on the Alamogordo Bombing Range for the Trinity test. To prepare, the military constructed a base camp with high-security measures; 12 soldiers (unspecified) and 200 laborers built and paved miles of roads to transport materials and disassembled pieces of the plutonium implosion device to the test site, erected poles for large amounts of electrical wires and cables to provide the power that would detonate the weapon, and built three observation bunkers and two towers for the experimental detonation (AHF, 2014b; Los Alamos MainStreet, 2020).

The plutonium implosion device was carefully transported to the site in several pieces and assembled in the McDonald ranch house near the 100-foot tower from which it would be dropped (sources do not state whether military personnel did the transportation) (White Sands Missile Range Museum, n.d.). On July 16, 1945, when it was detonated, it released 18.6 kilotons of TNT equivalent power which instantly destroyed the tower and melted the surrounding sand into a glassy composite subsequently named trinitite (DOE, n.d.d).

The blast itself was reported to have been seen 160–200 miles away (Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center, n.d.; Grant, 2020). Those closest to it were stationed at three observation bunkers 10,000 yards (approximately 5.7 miles) north, west, and south of the tower. Both scientists and service members were in these shelters, made of wood and protected by concrete and earthen barricades (NPS, 2023f), to observe and measure the effects of radiation during and after the test (AHF, 2014). Manhattan Project leaders observed the explosion from a shelter 20 miles from ground zero. A detachment of 144 soldiers was available for evacuation of nearby population centers if needed; a crew of technicians monitored conditions around the test area and was prepared to alert the detachment if an evacuation became necessary.

The military presence at Alamogordo included 125 military police guarding and maintaining the base camp. Likely, most of them came from the Los Alamos detachment (U.S. Army, n.d.). Military police detachments began arriving in fall 1944 to set up security checkpoints (U.S. Army, n.d.); they patrolled the site on horseback and in Jeeps (Los Alamos MainStreet, 2020). The reported number of service members at Los Alamos for the Trinity detonation was 425.4 The connection between Los Alamos and Trinity was kept secret, and soldiers who worked at Trinity were not informed of its purpose (Los Alamos MainStreet, 2020).

Supplementary military personnel included maintenance staff to keep the generators, well pumps, and power lines running. Up to 45 PED members were sent to the Trinity site in the lead-up to the implosion device test in 1945. They served as mess hall crew, constructed and maintained buildings, kept the generators operating, and generally supported all activities at base camp and the surrounding area (White Sands Missile Range Museum, 2020). When the test date neared, additional PED personnel were sent from Los Alamos. They were stationed about 18 miles from ground zero at Trinity and would aid in any potential evacuations of nearby communities within the likely fallout path (AHF, 2017b).

RESEARCH LABORATORIES

Among the 13 sites listed in the statement of task are two research laboratories: the University of Chicago’s Met Lab and Ames Laboratory at Iowa State College (now Iowa State University). This section highlights potential radiation exposure risks for workers at both facilities. Although no information was found on military personnel involved in the research, further investigation into university archives and the Ames Laboratory itself

___________________

4 Personal communication, Patricia Hastings, chief consultant, Health Outcomes Military Exposures, Department of Veterans Affairs, September 17, 2024.

may offer additional information. No epidemiologic studies of workers were identified for either location.

University of Chicago, Illinois

In January 1942, the University of Chicago was selected as the center of the Manhattan Project’s research to determine whether a fission chain reaction could be created and controlled, to subsequently develop a nuclear weapon (UChicago News, 2024). The Met Lab designed reactors called piles, and researched how to develop a sustained, controlled nuclear chain reaction and subsequent methods for separation techniques to extract plutonium from irradiated uranium (DOE, n.d.e; OSTI n.d.k). The scientists considered multiple methods of separating plutonium, eventually deciding that a bismuth phosphate process would be the most successful (OLM, n.d.a). Exposure to radiation at the Met Lab would have been minimal as the work with plutonium prior to the construction of the Oak Ridge X-10 reactor involved such small quantities of uranium. The laboratory’s chemical section successfully separated a weighable sample of plutonium in August 1942; under the unused Stagg Field, it began to build a 20-foot-tall stack of graphite and uranium blocks. This reactor was known as Chicago Pile 1 (CP-1); on December 2, 1942, it produced the first sustained nuclear chain reaction (NPS, 2023b).

After this successful reaction, CP-1 paved the way for developing Oak Ridge’s X-10 Graphite Reactor, and later the massive plutonium-producing reactors at Hanford (NPS, 2023b; OLM, n.d.a). In spring 1943, the Met Lab expanded off campus for safety and security reasons; CP-1 was reassembled as CP-2 and CP-3 was built—along with access roads, laboratories, and service buildings—approximately 25 miles southwest of Chicago.5 Unlike these later nuclear reactors, the CP-1 reactor operated at such low power that it required no shielding or cooling (NPS, 2023b). During its peak operations, the Met Lab employed 2,008 staff (U.S. Army, 1946c). No information was found regarding military members, including whether any were on site (AHF, 2022a; Holl et al., 1997; Norris, n.d.; OSTI, n.d.c). Records for the Met Lab can be found at Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago Library.

___________________

5 After the end of World War II, the Met Lab became the first national laboratory, known as Argonne National Laboratory. Today, the Chemistry Building, in which some of the research for CP-1, CP-2, and CP-3 was conducted, is a National Historic Landmark (OLM, n.d.a).

Iowa State, Ames, Iowa

In 1942, the Ames Laboratory was created as a chemical research and development program to complement the physics program of the Manhattan Project (Goldman, 2000), serving initially as an offshoot of the University of Chicago Met Lab. It focused on the chemical and metallurgical aspects of plutonium and uranium. Overseen by Frank Spedding at Iowa State College, the Ames Project developed into its own research program of the chemistry and metallurgy of plutonium. He and his colleagues created the “Ames Process” for preparing pure uranium metal that originally involved mixing powdered uranium tetrafluoride (green salt) with calcium, placing the mixture inside an iron pipe, and heating it to 2,730°F, where the contents reacted to form a 35-gram ingot of pure uranium metal (ACS, 2022; Chem Europe, n.d.). By September 1942, Ames generated more purified uranium into a single ingot than had ever been produced before, and after that experiment, production increased drastically. This process revolutionized the purification of uranium metal, and by 1945, Ames had become the primary supplier for the Manhattan Project.

In December 1942, several tons of uranium were shipped from Ames to the University of Chicago Met Lab to be used in the first controlled nuclear chain reaction inside CP-1; Ames provided approximately 30% of the uranium used in the experiment (Ames National Laboratory, n.d.; NPS, 2023h). Production of pure uranium at the Ames Project was scaled up to over 910 tons between 1942 and 1945. The laboratory also created methods of preparing and casting thorium, cerium, and beryllium for the Manhattan Project and later provided 90% of the uranium for the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge.

Workers at the Ames Laboratory could have been exposed to radioactive waste from uranium purification. No information was found on the number of service members who may have been part of the Ames effort. According to a written public comment received,6 “the Iowa State University archives and probably the Ames Laboratory maintains some level of records of the Ames Project, including the monthly reports sent from Ames to its reporting organization, the Met Lab at the University of Chicago” (Ames National Laboratory, 2014; Futrell, 2014). Further investigation of these records may confirm whether there were military personnel at this site. Additionally, the comment noted that there were “thousands of Navy V-12 officer training program candidates at Ames during the war that occupied many of the dormitories and took classes in university classrooms.”7

___________________

6 Personal communication, Donald Browne, public commenter, May 5, 2024.

7 Ibid.

MINING AND MILLING

The Manhattan Project’s success hinged on a robust supply chain, including mining and milling uranium ore. To secure it, the project turned to various locations across the United States, including Monticello and Uravan, with the assistance of contracted private mining companies, such as the Vanadium Corporation of America and the United States Vanadium Corporation. Most U.S. uranium mining and milling resulted in large volumes of low-level radioactive residues, known as mill tailings, which typically contain radioactive material, such as thorium, radium, and radon, and some low concentrations of nonradioactive metals (DOE, 1997).

The milling and refining of uranium ore to remove as many impurities as possible and generate materials that would be usable for the enrichment factories and production reactors involved four basic conversion steps. First, the ore needed to be made into black oxide and soda salt. Next, the black oxide and soda salt had to be converted into orange oxide and then brown oxide. Third, the brown oxide needed to be converted to green salt. And, finally, the green salt was converted to uranium hexafluoride or uranium metal (OSTI, n.d.j).

Monticello, Utah

In 1942, the Defense Plant Corporation, under the Department of War, funded the construction of a vanadium plant operated by the Vanadium Corporation of America and used solely for the Manhattan Project (Chenoweth, 1985b; Rimrocker Historical Society, 2016; U.S. Army, 1947b). Vanadium is a rare ductile metal used in many different alloys, for hardening steel, and in nuclear reactors. In January 1943, the plant’s owners agreed to produce a uranium-vanadium sludge at the Monticello Mine Tailings site near Monticello that was sold to the Manhattan Project. It was shipped from Utah to the Vitro Manufacturing Company in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, for further processing (Chenoweth, 1997). In February 1944, the Monticello plant was closed, but in 1945, the Vanadium Corporation of America leased it from the Metals Reserve Corporation, a federal government agency, which processed and purchased the stockpiled uranium-vanadium sludge directly through 1946, when the plant once again ceased operations (Chenoweth, 1985a; U.S. Army, 1947b). The mill tailings that remained after uranium had been extracted from the ore were used throughout Monticello for construction. The workers at the vanadium plant were exposed to the waste products from the sludge processing, which were likely radioactive. No information was found about service members at Monticello during this time, and no studies of workers were identified.

Uravan, Colorado

The United States Vanadium Corporation established the company town of Uravan in 1936 in western Colorado as the site of a carnotite (potassium uranium vanadate radioactive mineral) ore mine. The ore deposits, which contained small amounts of uranium, were initially more valued for their vanadium (AHF, 2022c). However, in 1942, with the growing need for uranium, MED entered into a contract with the corporation to convert these uranium-containing deposits into uranium sludges. That same year, the Army Corps of Engineers built a mill at Uravan to process uranium and vanadium (Henseler, 2023; Intermountain Histories, 2025; Rimrocker Historical Society, 2016; U.S. Army, 1947b). The Uravan carnotite deposits and the other carnotite mines on the Colorado Plateau averaged approximately 3 tons of uranium sludge per day and provided 14% of the total uranium acquired for the Manhattan Project (AHF, 2022c). Throughout World War II, Uravan workers mined and milled uranium for the Manhattan Project; however, wartime secrecy allowed the Manhattan Project to publicly admit only to purchasing the vanadium, while avoiding acknowledgment of any of the work done by uranium miners at Uravan.

The site’s Manhattan Project–related activities took place between 1943 and 1946 and mostly entailed processing and then shipping uranium sludge to Oak Ridge. To maintain security and confidentiality, the Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation created the Union Mines Development Corporation to deflect suspicion from Uravan’s activities. The Union Mines Development Corporation, led by Major Paul Guarin, conducted field examinations and covert surveys of uranium sites through 1946 under the cover of a large international mining company interested in other metals (AHF, 2022c). Workers at the Uravan processing mill and mine could have been exposed to the radioactive waste from uranium extraction and processing.

VA provided the committee with a list of military personnel at Uravan between June 19, 1943, and August 6, 1945. DOE Office of Legacy Management supplied the list, and it contains the names, locations, work classifications, and service dates for personnel working primarily in Colorado, including those assigned to Uravan. It includes 80 service members, which is the only evidence of a military presence at the site identified by the committee.

The Uravan mill closed in 1984. Much of the radioactive waste from the mill and plant were buried onsite (Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, 2025). By mid-1985, the town of Uravan was uninhabited, and all buildings were demolished. It was declared a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1986; that same year, environmental cleanup efforts began that were determined to be complete

by 2008 (Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, 2025; Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2022).

A cohort mortality study of Uravan residents was conducted in the early 1980s, with a follow-up study published in 2007. The studies examined mortality among 1,905 adult men and women, alive after 1978, who lived in Uravan for at least 6 months between 1936 and 1984, compared with the general U.S. population (Austin, 1986; Boice et al., 2007). Their military status is not available from the publications, and neither is the number of veterans who lived in the town in the years of interest. Overall mortality was not elevated compared with the general U.S. population, but a statistically significant increase in lung cancer mortality was observed among the subset of 459 residents who had worked in underground uranium mines (SMR = 2.00; 95%CI 1.39–2.78).

COMPONENT FABRICATION

The Manhattan Project’s goal of creating a nuclear weapon required constructing a neutron initiator, a device designed to trigger the fission chain reaction. As development of the weapon progressed, it was proposed that the trigger be a polonium-based modulated neutron initiator (a device that releases a burst of neutrons) rather than spontaneous fission. To develop and produce this essential component, MED contracted with the Monsanto Chemical Company, leading to the establishment of the Dayton Project in Dayton, Ohio (Thomas, 2017; U.S. Army, 1947a). It conducted the research necessary to create this initiator using plutonium and polonium (Po-210) purification and production. While many Manhattan Project activities occurred in remote locations, the Dayton Project was spread across the urban landscape of the city.

Beginning in 1943, Charles Allen Thomas and those working on the Dayton Project created techniques for removing polonium from lead dioxide ore and bismuth targets, shipped from Oak Ridge, that had been blasted by neutrons in a nuclear reactor before transport to Dayton (U.S. Army, 1947a). In 1944, it was proposed that combining Po-210 with beryllium could create the right reaction to trigger the weapon (AHF, 2022b). The polonium was shipped to Los Alamos, where it was built into the neutron initiators. Workers on the Dayton Project were exposed to radioactive bismuth, polonium, and plutonium.

The Dayton Project was known to have 30–40 SED members (Gilbert, 1969). Armed guards provided 24-hour security at the research and production locations associated with the Dayton Project, specified as units III and IV. The official history of the Dayton Project noted that 43 individuals were assigned to “protection services” by December 1946; however, it is not clear if these guards were military police or civilian employees (Thomas, 2017).

WASTE STORAGE

The Manhattan Project activities relied on a complex network of operations at multiple sites across the United States, many of which generated radioactive and chemical waste streams. While several of the Manhattan Project sites in the committee’s statement of task also had waste storage as part of their larger processes (such as Hanford and Oak Ridge), this section focuses on those sites which were solely created for waste storage purposes (Gephart, 2003; OSTI, n.d.l). The three St. Louis sites in the statement of task are not typically thought of as Manhattan Project sites because the dates when they received waste leading to contamination are beyond August 15, 1947; however, they are examples of the lasting environmental and potential public health impacts of the Manhattan Project.

St. Louis, Missouri

In 1942, Mallinckrodt Chemical Works began processing uranium in downtown St. Louis under contract with the Manhattan Project. It became the first industrial-scale producer of uranium metal and uranium oxide (St. Louis Site Remediation Task Force, 1996).8 The uranium was extracted from pure uranium ore, a process that produced radioactive waste. The waste included uranium-thorium, “relatively insoluble” thorium monazite, pitchblende raffinate, radium-bearing wastes, barium cake residue, and several stable metals, such as cobalt, nickel, and copper (Kaltofen et al., 2018; St. Louis Site Remediation Task Force, 1996). Acids and solvents were also used in the process and contributed to waste (DOE, 1997). The ore was shipped elsewhere to be purified, enriched, and used in the Manhattan Project.

The waste generated by the uranium refining to purified uranium oxide process used by Mallinckrodt Chemical Works is tied to the three specific St. Louis sites, although neither the Mallinckrodt Chemical Works itself nor the surrounding area was included in the statement of task. Beginning in 1957, Mallinckrodt Chemical Works operated the Weldon Spring Uranium Feed Materials Plant west of St. Louis under contract to the AEC. The company moved its refining and processing operations from downtown St. Louis to Weldon Spring when the new plant opened. The site was originally the Weldon Spring Ordnance Works, where the Atlas Powder

___________________

8 Mallinckrodt Chemical Works and the uranium refining it performed was only one company and one step in the Manhattan Engineer District’s uranium processing complex. Additional companies were contracted to produce and refine uranium. These activities generated industrial wastes at each site, which required remediation efforts decades later, along with continual monitoring for health and environmental concerns. It remains unclear whether or how many of these uranium refining and processing facilities included military personnel.

Company manufactured trinitrotoluene (TNT) and dinitrotoluene during World War II. Mallinckrodt produced uranium feed materials at Weldon Spring until 1966 (DOE, 2004; EECAP, 2024; EPA, n.d.; OLM, 2011b). The plant closed, and production buildings were buried in the Weldon Spring Quarry. A large-scale draining and remediation effort at the site became part of the cleanup conducted by the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP)9 overseen by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; cleanup was completed in 2001.

The committee heard from St. Louis–area historian Gwendolyn Verhoff that although the statement of task lists only the three sites associated with Manhattan Project waste, these do not exist in a vacuum but rather are connected to several other uranium processing sites and waste disposal sites in the area. The uranium processing waste from Mallinckrodt was stored at the St. Louis Airport Project Site. However, due to inadequate storage practices, radioactive materials leaked into nearby Coldwater Creek, contaminating it and surrounding areas. The West Lake Landfill also received and stored the radioactive waste from uranium processing, which was then used for landfilling operations (Missouri Department of Natural Resources, n.d.).

These waste streams have led to remediation studies and environmental cleanup efforts in the St. Louis area over several decades and served as the impetus for the congressional language resulting in this feasibility assessment. No evidence of military presence during the Manhattan Project was found at Mallinckrodt or any of the specified St. Louis sites.

Milder et al. (2024b) evaluated health risks among 2,514 White male employees who worked at least 30 days between January 1, 1942, and December 31, 1996, at Mallinckrodt Chemical Works; the cohort was followed through 2019 for vital status. This study was a follow-up to two studies of this workforce (Dupree-Ellis et al., 2000; Golden et al., 2022). Radiation doses were estimated from film badge records, records of occupational chest X-rays, uranium urinalysis, radium intake through radon breath measurements, and ambient radon measurements. Silica dust exposure from pitchblende processing was also estimated. The number of veterans in the cohort and what proportion of it worked 1942–1947 are not stated. The authors found an excess of brain cancer mortality in the workers compared with the U.S. population (SMR = 1.79; 95%CI 1.14–2.70) but no statistically significant radiation dose response for brain cancer. Kidney cancer mortality was statistically significantly elevated in dose–response models (HR at 100mGy = 2.07; 95%CI 1.12–3.79), as was cardiovascular disease (HR at 100mGy = 1.11; 95%CI 1.02–1.21).

___________________

9 The Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program, established in 1974, is intended to remediate sites where radioactive contamination remained from Manhattan Project and early Atomic Energy Commission operations.

St. Louis Airport Project Site

In 1946, the U.S. government acquired property near the city of St. Louis–owned airport (St. Louis Airport Project Site;10 the Wabash Railroad and Coldwater Creek areas) via eminent domain, to store uranium processing residues from the Mallinckrodt facility. Between 1948 and 1952 (after the period of interest for this feasibility assessment), Mallinckrodt Chemical Works decontaminated two of its processing plants in north downtown St. Louis, trucking much of the waste and debris to this site (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.b). It transported approximately 133,000 metric tons of waste to the St. Louis Airport Project Site (Kaltofen et al., 2018), including pitchblende raffinate residues, radium-bearing residues, barium sulfate cake, Colorado raffinate residues, and contaminated scrap (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.a). Much of the radioactive waste was placed in storage drums stacked across the site. Scrap metal and other bulk waste were stored in large covered and uncovered piles in the ground. Some contaminated materials and scrap iron were buried in other parts of the property (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.a). Years of deterioration of the drums and piles from rain, wind, and other weather elements led to contaminated runoff and threatened to pollute Coldwater Creek as early as 1949. The property was fenced from entry by the public to limit direct radiation exposure (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.a). This material was not moved for almost 20 years, as Mallinckrodt Chemical Works officials were concerned that doing so would harm their employees (Kauffman et al., 2023).

Ownership of the airport storage site transferred to the AEC in 1947. AEC surveyed the site in 1965 and found that 121,050 tons of uranium residues and contaminated material remained (St. Louis Site Remediation Task Force, 1998). In 1966, AEC sold a large portion of the waste material to the Continental Milling and Mining Company for recycling. This material was then trucked from the St. Louis Airport Project Site to the Hazelwood Interim Storage site (also referred to as the Latty Avenue Site) in St. Louis city (St. Louis Site Remediation Task Force, 1998). Following a transfer of ownership to the Commercial Discount Corporation of Chicago, the waste was dried and shipped to Colorado. After removal of the waste from the St. Louis Airport Project Site, onsite structures were demolished, buried, and covered with 1–3 feet of uncontaminated fill material. Although these activities reduced the surface concentrations, buried deposits of uranium-238, thorium-230, and radium-226 remained (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.b).

___________________

10 This is not the same site as the St. Louis Lambert International Airport.

In 1989, Congress placed the St. Louis Airport Project Site and the Latty Avenue site on a priority list for environmental cleanup (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.b). Until 1997, DOE (the successor agency of AEC) was the lead agency responsible for the cleanup of the former. In 1997, DOE proposed removing radioactive contaminated materials immediately adjacent to Coldwater Creek at the west end of the St. Louis Airport Project Site and transferring them to a licensed out-of-state disposal facility. In October 1997, Congress transferred the cleanup efforts from DOE to the Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis District, which remediated the remainder of the site in accordance with the North County Record of Decision, issued in September 2005. More than 600,000 cubic yards of contaminated material were removed over 9 years. On May 30, 2007, a formal closing ceremony took place, and upon completion of the remediation by FUSRAP, responsibility for the long-term management of the site reverted to DOE (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.b). No documentation regarding the presence of military personnel during the Manhattan Project at this site was found.

Coldwater Creek

Coldwater Creek, a tributary of the Missouri River, runs alongside both the St. Louis Airport Project and Latty Avenue sites. After the deterioration of storage drums and weathering of open piles at the St. Louis Airport Project Site, radioactive waste began to leak into this nearby creek, likely as early as 1949 (Rosenbaum, 2024). Radioactive waste materials from the uranium extraction process performed at Mallinckrodt Chemical Works slowly contaminated both the soil and water of the creek over several decades (ATSDR, 2016; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.b). An investigative article in the local newspaper said that in 1966, the Continental Milling and Mining Company purchased the waste from the U.S. government and transferred the barrels to Latty Avenue, where it was stored in open containers. Latty Avenue is adjacent to Coldwater Creek, and it is likely that natural elements, such as wind and rain, led to leaching of the waste and further contamination of the creek (Kite, 2023). In 1989, EPA identified low-level radioactive contamination from thorium-230, a product of uranium decay, on several residential St. Louis County properties abutting Coldwater Creek (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.b). In 1981, Oak Ridge National Laboratory prepared a radiological survey of Coldwater Creek, published in 1984, which “showed elevated levels of U-238” (ATSDR, 1991). Following this report, EPA listed it as “one of the most polluted waterways in the U.S.” (Kite, 2023). Ongoing efforts to remediate it are being conducted by the Army Corps of Engineers (Rosenbaum, 2024), which assumed cleanup duties from DOE in 1997 (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, n.d.b).

No peer-reviewed studies exist of individuals who either worked at or lived in the areas of Coldwater Creek, St. Louis Airport Project Site, or West Lake Landfill. However, health assessments focused on these areas have been published by the state of Missouri and ATSDR. The Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services published a community-level (ecologic) study in 2014 that evaluated cancer risk in eight zip codes in the area of Coldwater Creek. Cancer cases observed in the zip codes were compared with the expected number based on the rest of the state of Missouri from 1996 to 2011. Statistically significantly elevated standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) for the eight zip code areas were observed for leukemia (SIR = 1.11; 95%CI 1.01–1.21), female breast cancer (SIR = 1.08; 95%CI 1.04–1.12), colon cancer (SIR = 1.07; 95%CI 1.02–1.13), prostate cancer (SIR = 1.18; 95%CI 1.13–1.23), and bladder cancer (SIR = 1.13; 95%CI 1.05–1.21). Observed thyroid cancer cases were statistically significantly lower than expected (SIR = 0.75; 95%CI 0.65–0.85). Risks specific to military veterans were not part of this community study, although some residents may have been veterans.

In 2019, ATSDR released a public health assessment that evaluated community exposures related to Coldwater Creek. It used available environmental data and community information to evaluate whether people playing or living near the creek have or had harmful exposures to radiological or chemical contaminants. Four main conclusions were presented:

- Radiological contamination in and around Coldwater Creek, prior to remediation activities, could have increased the risk of some types of cancer in people who played or lived there.

- ATSDR does not recommend additional general disease screening for past or present residents around Coldwater Creek.

- ATSDR supports ongoing efforts to identify and properly remediate radiological waste around Coldwater Creek.

- Other exposure pathways of concern to the community could have contributed to risk. ATSDR is unable to quantify that risk (ATSDR, 2019, p. iii–v).

West Lake Landfill

In 1939, the West Lake Quarry Company opened a limestone quarry in Bridgeton, Missouri. It remained open and operational through 1985; however, in the early 1950s, a portion of it was used for landfilling of municipal solid waste (Missouri Department of Natural Resources, n.d.). After the radioactive waste material was shipped from the St. Louis Airport Project Site to the Latty Avenue Storage Site, much of it was dried and shipped to Canon City, Colorado, although approximately 8,700 tons

of barium sulfate cake from the Manhattan Project remained at Latty Avenue. In 1973, this leached barium sulfate and other radioactive waste material from Latty Avenue was mixed with approximately 38,000 tons of soil and transported to West Lake Landfill, where it was used for landfilling operations (Missouri Department of Natural Resources, n.d.; St. Louis Site Remediation Task Force, 1998). The West Lake Landfill has become an EPA Superfund cleanup site (EPA, 2023). As this site was a product of the cleanup efforts of Latty Avenue, it is a potential source of “thorium-containing particulate matter” (Kaltofen et al., 2018) but not a site specific to the Manhattan Project, and the activities occurred after the dates of interest. Additionally, no documentation exists for a military presence or involvement with transporting the waste material to the West Lake Landfill.

Lake Ontario Ordnance Works, New York

In Niagara County, 7,500 acres of land, including LOOW, was purchased by the Department of War (which became the Department of Defense in 1949) in 1941. This site was initially used to manufacture TNT until 1943, when the need for TNT decreased and the need for uranium became much more pressing (U.S. Army, 2007). After the closure of the LOOW in 1944, 191 acres of the site were converted into the Niagara Falls Storage Site (OLM, 2011a; U.S. Army, 2007). In 1944, MED began using the site to store radioactive residues and wastes that resulted from the processing of uranium ores (pitchblende) generated at the nearby Linde Air Products facility in Tonawanda, New York.11 Additional residues were brought to the site through 1952 (U.S. Army Corps Engineers, 2024, 2025).

In 1981, the New York State Assembly Task Force on Toxic Substances issued an interim report to the New York State Assembly Speaker, Stanley Fink (New York State Assembly Task Force on Toxic Substances, 1981): The Federal Connection: A History of U.S. Military Involvement in the

___________________

11 The Linde Air Products Division of Union Carbide Corporation operated two facilities in the Buffalo and Tonawanda, New York, areas 1941–1946. Linde Air Products processed uranium-235 and produced nickel for the gaseous diffusion barrier used in the K-25 Plant at Oak Ridge. At the Tonawanda plant, uranium was refined into black oxide, producing approximately 8,000 tons of sludge or tailings. The liquid waste was drained into wells and the public sewage system, then flowed into the Niagara River. The 1981 New York State Assembly Task Force report found that Linde Air Products disposed of “37 million gallons of radioactivity liquid chemical wastes in shallow underground wells located beneath the Linde Property” (New York State Archives) and that both “the Army and Linde were well aware that this method of disposal would further contaminate Linde’s wells and the wells of Linde’s neighbors in the surrounding region.” By 1995, it had become known that in 1939–1946, the Tonawanda plant not only pumped liquid wastes into bedrock wells but discharged overflows directly into nearby Two Mile Creek (OLM, n.d.b).

Toxic Contamination of Lovel Canal and the Niagara Frontier Region examined MED activities in the Buffalo/Niagara area. The report found that the Manhattan Project’s use of LOOW as a storage and disposal center for radioactive materials and wastes “created a continuing environmental hazard over the past thirty years” (p. viii of Summary of Findings and Recommendations). The task force found that radioactive waste buried and stored onsite had migrated offsite through the air and surface drainage systems. In 1982, DOE began cleanup and consolidation of the wastes and residues in an earthen containment cell constructed on the property (Stephens and Stephens, 2024; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2025).

The Niagara Falls Storage Site continues to operate and now includes a 10-acre interim containment structure for radioactive waste and residues (DOE, n.d.b; OLM, 2011a). The Army Corps of Engineers has been tasked with managing its cleanup and remediation since 1982 through FUSRAP, which performs routine testing and monitoring of the waste containment structure. When it was built in 1986, the facility only had a 25- to 50-year life-span; therefore, a more permanent solution to the waste issue remains a priority (Benson, 2023).

Little information is available on either the number of workers at LOOW 1942–1947 or a military presence at the site. Workers would have been exposed to chemicals associated with TNT production. Possible exposure of veterans may have occurred when transporting the waste, but records of who performed such tasks were not found.

No epidemiologic study has been identified for LOOW or Niagara Falls Storage Site workers or service members. Their employees, and contractors and subcontractors who worked between January 1, 1944, and December 31, 1953, are part of National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Special Exposure Cohort. However, no technical documents on the site are available from NIOSH. In a technical assessment for the LOOW special exposure cohort, NIOSH found no external exposure records were available before March 1949, and insufficient information is available to estimate the potential internal exposure of workers (Page, 2009).

SELECT MANHATTAN PROJECT SITES NOT INCLUDED IN THE STATEMENT OF TASK

The size and complexity of MED far exceeds the limited number of sites specified in the statement of task. Although this feasibility assessment was limited to select sites in the continental United States with Manhattan Project activities 1942–1947 and excluding atmospheric or weapons testing, a number of other sites with a military presence were not included in the statement of task, including production facilities, research laboratories,

supply units, and other mining, milling, and refining operations. Figure 3-1 is by no means a comprehensive depiction of all sites but was generated by the committee to demonstrate the complexity and scale of the project. Some historians estimate that the total locations associated with the Manhattan Project exceed 200 (Wellerstein, 2019). The numerous contractors and subcontractors hired by the Army Corps of Engineers that made the Manhattan Project successful likely totaled 100 or more.12 In this section, the committee describes some of the Manhattan Project sites not included in the statement of task that had a documented military presence or exposures to known wastes that may be relevant to the lines of scientific inquiry in the task.

Other sites that contributed to the Manhattan Project conducted activities such as

- production of materials (e.g., P-9 Project for heavy water production at the Morgantown Ordnance Works, West Virginia, Wabash River Ordnance Works, Indiana, and Alabama Ordnance Works, Alabama) (Hewlett and Anderson, 1962; U.S. Army, 1947b);

- research (e.g., Radiation Laboratory at the University of California, Berkley, which led the development of electromagnetic enrichment of uranium using cyclotrons; the “calutrons” (modified cyclotrons) served as the basic enrichment instruments at the Y-12 complex at Oak Ridge) (OSTI, n.d.i);

- supply units and facilities (e.g., Hooker Electrochemical Company, Niagara Falls, New York, contracted to chemically process uranium-bearing slag as a precursor to uranium recovery; and Project X-100, Detroit, Michigan, contracted with the Chrysler Corporation to use several thousand workers to manufacture the 3,500 large, cylindrical metal diffusers to enclose the barrier material required to separate the uranium isotopes at the Oak Ridge K-25 gaseous diffusion complex);

- uranium mining and milling, including at Grand Junction and Durango, Colorado; and

- uranium refining (e.g., the Vitro Manufacturing Company in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, processed carnotite ores to recover radium-vanadium and uranium content to obtain uranium oxide, uranium sludge, radium and radioactive lead, and similar products).

Although important in their contributions to developing a nuclear weapon, these sites had no documented military presence or only a few military

___________________

12 See Hewlett and Anderson (1962) for the sheer volume of contractors and subcontractors that contributed to the successes of the Manhattan Engineer District.

officers assigned to overseeing the operations, but the majority of the personnel were contractor employees and administrators. Some of these sites are associated with a military base or ordnance works (for example, the ordnance works in Morgantown, Wabash River, and Alabama), but details regarding a military presence were not found. A selection of these other sites with a documented military presence is briefly described and presented by process: research laboratories, supply units and facilities, and milling and refining.

Research Laboratories

In addition to the University of Chicago Met Lab and Ames Project, several other Manhattan Project sites were involved with research on processes or materials. These research laboratories with a documented military presence include the Special Alloyed/Substitute Alloy Materials Laboratories (SAM Labs) at Columbia University, New York; Z Division, Los Alamos; University of Rochester; and Project Alberta, Wendover Army Airfield, Utah.

Special Alloyed/Substitute Alloy Materials Laboratories, New York

Although the SAM Labs at Columbia University received some of the first contracts from the federal government to carry out early research on the possible use of atomic energy and development of nuclear weapons, most of the research was conducted in the late 1930s, led by Ernesto Fermi at the University of Chicago, who was trying to demonstrate a chain reaction in natural uranium. In January 1942, MED scientific leaders decided to concentrate all reactor work at the University of Chicago Met Lab. SAM Labs scientists continued to research other uranium separation methods, including high-speed centrifuge technology and gaseous diffusion. After contracting with the M.W. Kellogg Company in early 1942, which provided industrial expertise, experience, and data from operations of its Pilot Plant No. 1, a small 12-stage apparatus informed the building and operations of the much larger Oak Ridge K-25 gaseous diffusion complex. Columbia University and MED representatives officially reorganized the research at the institution into the SAM Labs in 1943. By 1944, the SAM Labs employed nearly 1,000 scientists and workers, including SED personnel who helped to research and develop the gaseous diffusion process for the separation of uranium (AHF, 2022e). The Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation assumed managerial supervision of the SAM Labs for the Manhattan Project in February 1945.

The entry of the Kellogg Company into the MED led to the formation of the Kellex Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Kellogg that

participated in the Manhattan Project’s efforts to use gaseous diffusion to enrich uranium. For this, 100 SED personnel were assigned to New York and worked with Kellex employees on designing and engineering the K-25 plant site. Some of them were involved in developing gaseous diffusion barrier materials research and experiments carried out in the Nash Building of SAM Labs. Employees who worked in the Pupin, Schermerhorn, Havemeyer, Nash, or Prentiss buildings at the SAM Labs from August 13, 1942, through December 31, 1947, were determined to have both external exposure and potentially internal exposure to ionizing radiation from the processes (Harrison-Maples, 2008). As the SAM Labs work shifted to industrialization, some SED personnel were reassigned to Oak Ridge to work on the K-25 complex (AHF, 2022e; Jones, 1985). When small detachments of SED service members were assigned to work with private contractors, such as Kellex, or in small communities, MED transferred them to the Enlisted Reserve Corps.

Z Division Los Alamos, New Mexico

Although Los Alamos and Alamogordo are specified as sites of interest, a third New Mexico facility, Z Division of Los Alamos and located in Albuquerque, which became Sandia National Laboratory in 1948 (and separated from Los Alamos) was not included (LANL, 2024; Sandia National Laboratories, 2025b). Beginning in July 1945, it was associated with weapons development, particularly the nonnuclear components, research on future weapons development, testing, and bomb assembly (Sandia National Laboratories, 2025a). The wastes generated could fall under the committee’s charge, but the exact number of military personnel assigned to Z Division 1945–1947 was not available, nor were details about their specific duties (Truslow, 1973; U.S. Army, 1947c).

University of Rochester, New York

The Rochester Project at the University of Rochester conducted experiments on the effects of radioactive isotopes, including plutonium, uranium, and polonium, on humans as part of the Manhattan Project (ACHRE, 1994; AHF, 2017a; Georgetown University, n.d.; U.S. House of Representatives, 1986). The purpose was to study effects of small amounts of radiation on workers of the Manhattan Project, specifically to identify protection measures by “(a) determining a tolerance standard” for doses of radiation; (b) developing instruments to measure the exposure which these workers received; (c) determining by measurement which areas in the plants showed the greatest intensity of radiation; (d) determining the amount of contamination of worker clothing with radioactive materials; and advising what protections should be taken to safeguard the workers” (Dowdy,

1945, p. 4). The experiments were conducted in the Manhattan Annex of Strong Memorial Hospital at the university (ACHRE, 1994; AHF, 2017a; U.S. House of Representatives, 1986). The ward for studying the metabolic effects of radioactive materials was purposefully located across the street from the medical school (AHF, 2022g). It took 5 months to build and outfit the annex, and by the end of World War II, 350 people worked in it. The workforce included members of the Army Corps of Engineers who designed and were responsible for the operation, maintenance, and safety of several unique types of dust chambers for these experiments, and officers from the Industrial Division of the Medical Section of MED who visited plants and reported to the Rochester Project. Military police guarded the Manhattan Annex, which was only accessible through an underground tunnel (Dowdy, 1945).

Project Alberta, Utah