Law Enforcement Use of Probabilistic Genotyping, Forensic DNA Phenotyping, and Forensic Investigative Genetic Genealogy Technologies: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 4 Forensic DNA Phenotyping

4

Forensic DNA Phenotyping

OVERVIEW OF FORENSIC DNA PHENOTYPING (FDP)

Alicia Carriquiry, Iowa State University and chair of the workshop planning committee, moderated this session of the workshop, which focused on FDP (see Box 4-1). The panel featured speakers with expertise in biology, biotechnology, anthropology, and criminal legal defense reform. The session examined the potential of FDP to function as an investigative tool while also emphasizing the significant ethical, legal, and social challenges associated with its use. Several participants called for careful consideration of these issues to ensure that FDP is used responsibly and effectively in the criminal legal system.

Presentations began with Susan Walsh, Indiana University Indianapolis, who explained that FDP is used to infer likely phenotypic characteristics (such as eye, hair, and skin color) from DNA left at crime scenes. It is intended to provide investigative leads by predicting physical traits of unknown persons of interest based on their genetic material.

Walsh provided an overview of the different types of professionals that work on FDP. Researchers focus on identifying variants or genes that are associated with human traits and generally focus on appearance, age, or ancestry. Commercial partners develop tools that allow laboratories to use the information generated by the researchers. Many work with researchers and use the markers and models that researchers have provided, although others use their own methods. The public, said Walsh, tend to have a narrow view of FDP through “big splash news stories” that highlight specific cases.

BOX 4-1

Overview of Forensic DNA Phenotyping

The following overview reflects information shared in presentations from multiple workshop speakers. They should not be construed as consensus or exhaustive definitions of the topics discussed.

What is it? Forensic DNA phenotyping (FDP)* is a technique that aims to predict visible physical characteristics and biogeographical ancestry of an unknown person from DNA evidence left at a crime scene, typically used for investigative lead generation. It is an investigative intelligence tool that provides information about likely physical traits from DNA to help inform or narrow a police investigation, rather than a means of definitive identification like traditional DNA profiling.

How does it work? FDP involves analyzing specific regions of DNA and applying predictive modeling to infer traits such as eye, hair, and skin color; age; facial features; and the geographic ancestry or ethnic background of a sample’s source. This is done by looking at how certain genes influence the expression of these visible characteristics. The goal is to generate investigative leads about the unidentified person’s appearance and origins when there is no match in criminal DNA databases. The predicted traits can then be used to focus the investigation on potential suspects, missing persons, or unidentified human remains.

Who is involved in its use? Generally, law enforcement agencies contract with private consultants and/or external vendors that offer FDP services and tools.

What is the scale of use? FDP is an emerging technique with increasing commercial availability. Though there are examples of its use by forensic laboratories in the United States, it has not been widely adopted. FDP is typically used for investigative lead generation rather than routine casework.

What regulations and/or guidelines apply to its use? In the United States, there is currently no federal law regulating FDP specifically, and most states do not have laws addressing FDP specifically.** The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Quality Assurance Standards, which became effective as of July 2020, provide guidelines for forensic DNA testing laboratories. While not mentioning FDP specifically, they cover validation requirements for new methodologies used in DNA analysis.

__________________

*The DNA technologies discussed at the workshop are not referred to with consistent terminology by forensic, law enforcement, and legal experts, with multiple variations on the names of the technologies discussed at this workshop. For consistency, the terms forensic investigative genetic genealogy, probabilistic genotyping software, and forensic DNA phenotyping are used across these workshop proceedings.

**Some states are considering new legislation to regulate FDP. For example, New York state legislators proposed Bill S. 226, “An Act to amend the executive law, in relation to prohibiting the use of DNA phenotyping in criminal prosecutions and proceedings.”

SOURCE: Definitions presented by Heather McKiernan and Craig O’Connor on March 13, 2024. Regulations and guidelines sourced from workshop discussions and presentations on March 13 and 14, 2024.

Looking for variants or genes associated with a trait is like looking for a “needle in a haystack,” said Walsh. Traits may be binary, categorical, or continuous, and the variants or genes can be highly or only slightly associated with the traits. Once relevant genes or variants are identified, they are combined to create a reliable tool that can be used for prediction. Walsh said that the data, methods, and models created by researchers in this field are published and peer reviewed. She emphasized that the process of FDP is designed to accumulate intelligence about persons of interest, not to identify a single suspect; the intelligence generated by FDP must be followed by normal police work to investigate further.

FDP predictions are group based, not individual, said Walsh. This means that the results will provide likelihood information on multiple traits and will highlight several potential phenotypes of interest. Rather than producing a single definitive prediction of an individual based on DNA, FDP provides information about the likelihood of several traits. Later, Walsh noted that in her scientific opinion, it is currently not possible to reliably predict facial morphology through FDP. She noted that facial morphology prediction could be possible in the future, and that she is working with other scientists to deepen understanding of the genetic formation of the face. For now, she reiterated, FDP does not enable law enforcement to point to a single individual but can inform police investigations.

Walsh explained the current state of evidence in appearance, age, and ancestry prediction. Associations are described with an area under the curve (AUC) metric that represents predictive value; an AUC of 1 would be a perfect prediction and an AUC of 0.5 would be comparable to “tossing a coin.” Predictions of brown and blue eye color are fairly accurate, with AUCs of 0.95 and 0.94. Hair and skin color predictions are slightly less accurate, with AUCs ranging from 0.72 for brown hair to 0.92 for red hair and 0.72 for pale skin and 0.96 for dark-to-black skin. Walsh stressed that while some of these predictions are fairly reliable, all of them will produce some false positives and false negatives. Other traits associated with a predictive gene or variant include eyebrow color, freckling, hair shape, and baldness. There is no DNA model available for continuous height prediction, given that hundreds of thousands of markers would be needed, and many environmental factors contribute to an individual’s height. The process for predicting age is slightly different and involves detecting and measuring methylated DNA regions; this process results in a quantitative output.

Ancestry prediction uses genetic data to infer the geographic origin of the person’s most recent ancestors, said Walsh. It can be conducted using select ancestry informative markers or large-scale genetic data, but the prediction is only as good as the reference population. Walsh stressed that ancestry prediction should not be used to predict a phenotype and vice

versa. Each assessment should be considered an independent test that helps accumulate information toward a fuller representation of the sample tested.

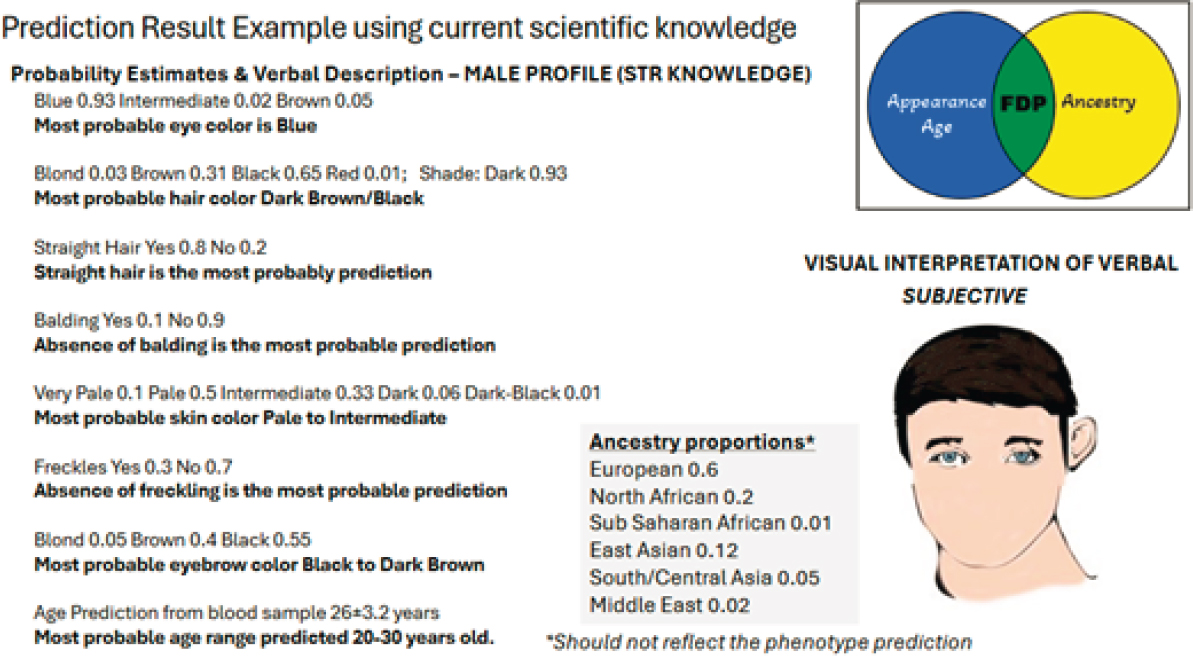

Walsh provided an example of the types of predictions that result from FDP analysis. She explained that currently, biologists can provide prediction results of the most probable physical traits associated with a DNA sample, for a discrete set of traits. While a most probable presentation of a trait (such as blue eyes) is indicated by the results, there is still a real possibility that the most probable presentation is not the actual presentation. Walsh noted that epistasis and epigenetics, fields where knowledge is actively evolving, can affect the expression of genes.

The results of FDP can also be translated into a possible visual interpretation, Walsh explained. Given the potential variability of traits, and the independent nature of each trait, Walsh noted that the most accurate visual representation of FDP results based on current science would include multiple images that offer simple visual indicators for discrete traits such as eye or hair color, hair texture, presence of balding, skin tone, presence of freckles, eyebrow color, and age prediction (see Figure 4-1).

Walsh concluded by emphasizing her views on the need for independent validation and peer review of genetic phenotyping tools used by law enforcement, both of the underlying science and of products of FDP, including the best practices for presentation of results. During the Q&A session, an audience participant noted that in addition, independent validation of software as it is deployed in the field is necessary to ensure reliable and accurate use of such technology.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR FDP USE BY LAW ENFORCEMENT

Opportunities

Asked to consider opportunities around law enforcement use of FDP (see Box 4-2), Walsh explained that for unsolved cases in which other investigative leads have gone cold, FDP can be used as part of normal police work to accumulate intelligence that may help narrow down a list of suspects or help generate leads in identifying a missing person. She explained that unlike traditional testing that compares a sample from a crime scene to a potential suspect, FDP generates information about what an individual may look like based on their genetic profile and can thus be a unique tool for lead generation. Walsh clarified that as an investigative tool, FDP intelligence is then followed by normal police work to investigate further.

These uses echoed those highlighted by Paul Belli, International Homicide Investigators Association, and Leigh Clark, Florida Department of Law Enforcement, in the law enforcement perspectives panel (see Chapter 1). Belli and Clark described previous examples of FDP use as a means of

SOURCE: Presented by Susan Walsh on March 14, 2024.

BOX 4-2

Opportunities and Challenges in Using FDP Identified by Workshop Speakers

Opportunities

Technological capabilities: FDP can generate predictions about an individual’s appearance based on their genetic profile, including hair color, skin pigmentation, freckling, and eye color. Emerging markers aim to predict body height and refine geographic ancestry. (Walsh)

Generating leads: FDP can be used in an investigative capacity for unsolved cases where other leads have gone cold, helping to generate leads, inform investigation priorities, narrow down suspects or find missing persons. (Walsh)

Challenges

Consistency and objectivity: The use and interpretation of FDP results by law enforcement can be influenced by human factors such as implicit bias, confirmation bias, and tunnel vision. Additionally, because FDP is often used as a last resort in attempts to generate leads, there can be limited evidence to independently corroborate predictions. (Brown)

Disparate impact: Because communities of color are overrepresented in the criminal legal system, any risks associated with the use of advanced forensic DNA technologies affect communities of color disproportionately. Insofar as it produces visual representations, FDP has risks similar to those associated with traditional police sketches, including racial profiling or misidentification, potentially leading to innocent people becoming the focus of investigations. (Brown & Martschenko)

Limitations of current science: There may be a gap between what the public believes is possible in the case of FDP and what the current science enables. It is important for the implementation of FDP for law enforcement investigative use to be independently validated and openly peer reviewed, hallmarks of the scientific enterprise. (Walsh & Martschenko)

SOURCE: Generated by the rapporteur based on workshop presentations from March 13 and 14, 2024.

generating investigative leads in the absence of other evidence for the identification of both suspects and of unidentified human remains, and as a tool for garnering renewed public attention for a case.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Uncertainty and Scope of Impact

Rebecca Brown, Maat Strategies, framed her presentation in terms of considerations related to law enforcement applications of FDP in the field, including questions around the potential for accuracy to be impacted when a tool moves from laboratory to field use, how relative accuracy can be misunderstood by law enforcement, and the need to carefully evaluate the utility of investing limited criminal justice resources in the use of FDP. Without careful regulation of investigative tools, suggested Brown, innocent people can inadvertently become the focus of investigations. She expressed the view that these applications’ relative value to crime solving may not outweigh potential risk to the public good. Brown pointed to an example of National Institute of Standards and Technology tests of facial recognition algorithms in nonlab settings, which found that accuracy rates varied widely between demographic groups, with certain racial demographics seeing higher rates of misidentification. She called for FDP models to undergo similar independent forensic validation to assess their accuracy on samples derived from real-world case studies, under the supervision of institutional review boards. Brown also suggested that in moving from the lab to real-world application, analysts should also account for environmental factors that influence appearance, such as body choices including diet, cosmetic surgery, makeup, or hair dye. To this point, Walsh and O’Connor both noted in previous presentations the extent to which genetic markers may vary from phenotypical presentation—particularly around racial identity. FDP involves probabilistic inferences, said Brown, which invite human factors, such as confirmation bias, implicit bias, and tunnel vision, to impact how the information is used. Brown expressed her concern that FDP application may be more prone to impact by problematic human factors. For example, law enforcement officers may exhibit confirmation bias and interpret FDP-generated information in ways that confirm their existing beliefs or may focus only on the direction suggested by FDP while ignoring other leads. Brown also noted an example where law enforcement use of FDP had previously enabled racial profiling. In that case, genetic evidence suggested that a Black person had committed a crime; police used this information to obtain DNA swabs from hundreds of Black and Hispanic men who had previously been arrested in the general area of the crime.

Brown noted that there are multiple examples of investigative tools being expanded beyond their original intended use. For example, color-based field drug tests were developed as a preliminary testing method; results were to be confirmed by laboratory testing. However, despite evidence about unreliability and even warnings from the vendors of the tests, these tests remain in use and are responsible for hundreds of thousands of arrests each year. Echoing Bradford in the earlier ethics panel, Brown emphasized the significant impact a false arrest can have on an individual’s life. It is essential, she suggested, that we carefully weigh the use of law enforcement technologies with the cumulative costs and harms to society. She urged the audience to ask themselves, “If the goal before us is to identify those tools best equipped to solve crime, given limited resources and our inability to control the psychological factors impacting investigations like tunnel vision and implicit bias, should this particular tool be employed?”

Understanding and Education

Brown offered her view of the potential risks related to law enforcement use of visual representations of suspects, particularly given the biases inherent in eyewitness and public response to these images. One of the most unreliable procedures used by law enforcement to identify a suspect is the traditional composite sketch, she explained. Innocent people have been arrested because they share resemblance to a composite. In addition, Brown explained that memory is malleable and can be altered through the viewing of a composite, leading to an inability to properly identify the actual perpetrator later. Finally, cross-racial misidentification is a common issue in wrongful convictions. Brown also noted her concern that the public may misperceive FDP-generated images as definitive images of a suspect rather than as an investigative tool.

In a previous panel featuring law enforcement perspectives, speakers noted that FDP is often used when other traditional forms of investigation have been unable to generate leads. Brown reiterated this point, noting that use of FDP in this context can mean there is little to no evidence to independently corroborate a phenotyping prediction or public identification of a suspect based on a phenotyping prediction.

“We cannot train our way out of the shortcomings of these tools,” said Brown. Implicit bias, confirmation bias, and tunnel vision are human factors that impact the way an FDP result is interpreted by law enforcement and members of the public.

Disparate Impact

The risks of FDP and other forensic DNA technologies fall disproportionately on communities of color, said Brown, pointing to existing evidence of racial profiling and DNA dragnets, and noting that these consequences can extend to wrongful arrest and conviction. Brown explained that there is the additional risk of reinforcing racial biases and stigmatizing certain populations.

Brown suggested that if law enforcement relies on FDP or other advanced forensic DNA technologies to the detriment of the communities they serve, trust will be eroded. Furthermore, relying on advanced forensic DNA technologies can waste resources that could be directed elsewhere. For example, there are thousands of untested rape kits, and thousands of drug arrests predicated on color-based drug tests. Brown suggested that investing in using validated tools in these areas would be a better use of limited resources.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

The presenters next discussed considerations for implementation.

Ethical Considerations

Matthias Wienroth, Northumbria University, offered an accounting of the state of the art of forensic science in terms of its engagement with ethics. Wienroth noted that both forensic analysts and law enforcement officials typically associate their roles with a moral duty to protect the public from harm. This is complicated, he noted, by the fact that this duty can come into direct conflict with other values, including fairness, equity, and public trust. Wienroth encouraged the audience to carefully consider efforts to weigh the risks and benefits of implementing advanced genetic forensic technologies, and to recognize that even in those cases where a technology leads to the resolution of the case, there can be significant costs.

Before continuing with the implementation of advanced genetic forensic technologies, Wienroth said that the public needs to ask several questions. Are laboratories capable of employing the statistical and probabilistic methods required to apply these approaches? Are service providers ready to discuss and address the limitations of technologies as well as challenges of application by forensic scientists and law enforcement officials in real-world settings? Are law enforcement processes prepared for reliably, usefully, and legitimately integrating new and emerging forensic genetics technologies into the practice of law enforcement and investigation? Are advanced forensic DNA technology practitioners working transparently? Are they aware

of the societal context in which they operate and what that means for their own practice? In moving forward, Wienroth suggested, we should consider ethics in law enforcement use of advanced forensic DNA technologies not as a hurdle that must be cleared, but as an embedded, everyday practice.

Frameworks for Governance and Oversight

To meaningfully implement this kind of ethics, Wienroth suggested, requires enforceable self-governance, with enforcement mechanisms that are both internal and external to the field. Wienroth proposed a framework for the ethical implementation of FDP that considers reliability, utility, and legitimacy (Figure 4-2). This framework emphasizes the need for reliable scientific methods, useful applications that genuinely aid investigations, and legitimate practices that are transparent and inclusive. Wienroth explained that this framework relies on effective governance structures, including independent validation and public reporting, which he said are necessary for overseeing the use of FDP.

Other speakers echoed Wienroth’s calls for governance and oversight and reemphasized the importance of public education and transparency around the use of advanced forensic DNA technologies. Walsh outlined methods for enhancing transparency and accuracy in law enforcement use of FDP. Specifically, she highlighted the need for peer-reviewed publications on the science behind the tool, prediction model design, and performance of the predictions on global independent test sets. She also identified a need for guidelines on how to understand and report results from FDP, and for education and training for users of the tool, law enforcement, and the public. Finally, Walsh called for standardized, publicly available sample sets to

SOURCE: Presented by Matthias Wienroth on March 14, 2024.

examine both the science of the method and the impact of result interpretation by law enforcement.

REFLECTIONS

Following the panelist presentations, Daphne Martschenko, Stanford University, offered her reflections. This panel discussion, she said, emphasized the importance of being very clear about terminology. Brown demonstrated the differences in how “accuracy” is understood in the laboratory, in real-world cases, and by the public. Wienroth identified reliability, utility, and legitimacy as important concepts, said Martschenko, but what do these terms mean to different actors? Who gets to determine what these terms mean? Martschenko emphasized that workshop discussions had made clear that problems arise when independent parties do not have the opportunity to inform decisions about what is reliable, beneficial, or legitimate. Reconciling the different understandings of the concepts in forensic DNA technologies may require educating the public, the media, and researchers about how technologies are used and understood downstream. Ultimately, “these tools should not be made available to those who do not have the training to use them or the education to know how to appropriately interpret findings,” said Martschenko.

The public release of FDP-generated images has the potential to bring groups of people under suspicion, and existing biases may be reinforced within the legal system. There is a fraught relationship between race and genetic ancestry, and describing race as biological rather than as a sociopolitical construct can have very harmful consequences, she said. Despite researchers’ best intentions, FDP predictions are often misunderstood as identifying specific individuals.

Multiple speakers at the workshop have emphasized the need for an agreed-upon threshold for scientific accuracy prior to implementation of technologies, as well as the need for independent verification, professional and ethical guidelines, and oversight and governance, said Martschenko. She said that while all of these are critically important, we need to be comfortable revisiting and adjusting the needs as technologies are implemented and evaluated. Furthermore, there is a need to answer fundamental questions about who defines the risks and benefits, and for whom justice is being served through the use of advanced forensic DNA technologies. If we do not address these issues, she said, “we create an environment that’s ripe for unaccountability, for ambiguity, and for mistrust.”

This page intentionally left blank.