Sex and Gender Identification and Implications for Disability Evaluation (2024)

Chapter: 5 Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender and Gender Diverse People

5

Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender and Gender Diverse People

This chapter provides an overview of gender-affirming care for transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people across the lifespan in response to questions in the statement of task. The chapter begins with a discussion of developmentally appropriate support for prepubescent gender diverse children; in contrast with prepubescent children with variations in sex traits (VSTs) (as described in Chapter 7), prepubescent gender diverse children do not require any gender-affirming medical interventions. However, psychosocial support for gender diverse children and their families may be critical to ensure a safe environment for these children to thrive, and this chapter describes these important interventions.

Next, the chapter describes gender-affirming medical care for people who have accessed puberty-delaying medication and/or gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) during puberty, including treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs, exogenous testosterone, or estrogens. This is followed by an overview of gender-affirming medical care for people who initiated GAHT and other care after puberty. The committee separated these two TGD populations—those that receive GAHT during puberty and those that receive it after—as their developmental and health trajectories may differ in some known respects (e.g., with regard to physical appearance and mental health), while the long-term benefits and risks of early medical intervention are under study and not yet fully understood. However, research to date clearly indicates that gender-affirming medical interventions during puberty and adolescence lead to reduced gender

dysphoria and increased mental health for TGD youth (Connolly et al., 2016; de Vries and Cohen-Kettenis, 2012; de Vries et al., 2011; Van Der Miesen et al., 2020).

Following this discussion, the chapter examines gender-affirming surgery, reviewing facial, breast, chest, and genital surgeries. Next, the chapter briefly discusses nonmedical gender-affirming interventions, such as chest binding, packing, and the practice of silicone injections—the latter not uncommon and with potential disabling consequences.

In addition to the medical interventions of hormone therapy and surgery, psychosocial support and mental health care are, for many TGD people and their families, of utmost importance in coping with gender dysphoria, as well as the social stigma attached to nonconformity in gender identity and expression. The latter leads to minority stress, which has been shown to negatively affect TGD people’s mental health and physical well-being (Delozier et al., 2020; Gosling et al., 2022; Pellicane and Ciesla, 2022; Pellicane et al., 2023; Valentine and Shipherd, 2018). The chapter provides an overview of TGD people’s identity development across the lifespan, and how families, peers, and mental health professionals can play an important role in facilitating resilience, health, and well-being. Finally, the chapter describes the wide variability in gender-affirming care accessed by TGD people across the life course.

PREPUBESCENT GENDER DIVERSE CHILDREN: DEVELOPMENTALLY APPROPRIATE PSYCHOSOCIAL SUPPORT

Until relatively recently, little attention has been directed toward prepubescent gender diverse children, most likely because, particularly in the United States, gender-affirming health care has been limited for minors of all ages. It is only more recently that gender health centers have proliferated in the United States, typically following the model of prioritizing medical care, and therefore serving only postpubertal children and their families. Nevertheless, the distribution of these centers varies significantly by geographic location, with less access to care in southern portions of the United States. Thus, care for gender diverse prepubescent children—who do not qualify for any medical interventions to affirm their gender diversity—has been less well understood clinically and empirically than care for older youth and adults.

More recently, however, increased attention has prioritized the experiences and needs of gender diverse children prior to puberty, although characterization of this population through research remains undeveloped. For the first time, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) included a separate chapter on best practices and recommendations for the care of prepubescent gender diverse children in the

Standards of Care Version 8 (SOC-8) (Coleman et al., 2022). This section of the SOC-8, based on an understanding of ethics, a review of research, and clinical expert consensus, draws on several foundational principles and frameworks extracted from clinical and developmental psychology, including ecological models and principles of developmental psychopathology. The text stipulates that gender diversity is an expected developmental variation and not a mental health disorder, and that attempts to “convert” a gender diverse child to be more gender typical of any given culture risks significant harm and should not be attempted. The chapter also emphasizes that gender expressions and identities may evolve over the course of childhood and later, and that children should be supported in gender fluidity over time.

Frameworks for Understanding the Development of Transgender and Gender Diverse Children

An ecological model of child development is rooted in the understanding that a child’s well-being and safety should be prioritized in all settings in which the child functions (e.g., home, school) (Belsky, 1993; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Lynch and Cicchetti, 1998) in order to foster positive mental health and adaptation over time. Additionally, a developmental psychopathology framework, established by a wealth of empirical research, demonstrates that childhood experiences are linked to trajectories of well-being that can continue from childhood through adolescence and into adulthood; these early life experiences may be predictive of resilience or the exacerbation of vulnerabilities and risks over time.

Early childhood is an important developmental period in many ways. Childhood is a time when a young person develops a schema or understanding of the world and of themselves, often based on their earliest relationships. As one example, much research demonstrates that secure caregiver–child relationships early in life are fundamental to positive development and continuing relationship stability over time (Hong and Park, 2012). When stress and adversity disrupt a child’s well-being and relationships, the effects can be broad and can negatively impact most or all aspects of the child’s mental health and function, including social, academic, emotional regulation, and somatic well-being (Nelson et al., 2020; Nurius et al., 2015). Thus, positive support and safety are important for a child’s quality of life, but also for ensuring that a child has the resilience, confidence, and support to adapt during important life transitions, including that from childhood to adolescence. Thus, the prepubescent years offer an opportunity to nurture characteristics—such as confidence, optimism, and a strong sense of self—that will facilitate a child’s resilience. Conversely, early-life adversities are harmful to children and are linked to a significant

array of negative mental and physical health outcomes, including trauma (Anda et al., 2010; CDC, 2021; Masten and Cicchetti, 2010; Shonkoff and Garner, 2012).

TGD youth experience significantly higher rates of adversity, such as family rejection, maltreatment, and bullying, relative to their cisgender peers, with risks for continuing and accumulating mental health disabilities. Research indicates that this type of chronic stress is associated with somatic/medical morbidities as well, both from direct exposure to violence to the impacts of chronic stress on somatic well-being. In addition, TGD children often encounter persisting gender minority stressors, including lack of recognition of their gender diversity (such as deliberate misgendering), exclusion from normative peer-related activities, and ostracism within and outside of families. Although risks associated with exposure to detrimental experiences are high, research also demonstrates that family and peer acceptance can mitigate these risks to well-being for TGD children (Cardona et al., 2023; Olson et al., 2016; Pariseau et al., 2019), and children supported in their diverse identities have been shown to be well adjusted (Olson et al., 2016).

Gender Stability

At this point, researchers are unable to reliably predict the stability of a diverse gender identity expressed during childhood. Much of the research published on the stability/instability of gender identity has been criticized, particularly for not using assessment measures in childhood that clearly and validly differentiate measures of gender identity from gender expression, and some of which measure only binary (versus nonbinary) gender identities (Ehrensaft et al., 2018; Olezeski et al., 2020). The invalidity of earlier research and the limited ability to measure diversity in gender identity in childhood create obstacles to identifying rates of TGD identity in prepubescent children and to understanding the needs of these children. Research on gender stability among prepubescent TGD children is limited but suggests that children who are the most assertive about their gender diverse identity experience more identity stability compared with their less assertive peers (Olson et al., 2022; Rae et al., 2019; Steensma et al., 2013). It is likely, however, that social context and acceptance may influence a child’s comfort and sense of safety in asserting a noncisgender identity, which may then complicate understanding of the occurrence and stability of gender diversity in these children. In general, as recommended in the recently published WPATH SOC-8, it is important to recognize that young TGD children may experience gender fluidity or gender evolution over time, which may be represented by inconsistencies in gender designations in medical records (Coleman et al., 2022).

Gender-Affirming Care for Prepubescent Children

The WPATH SOC-8, as well as a corresponding article (Tishelman and Rider, 2023), provides important recommendations for mental health approaches to protective care for prepubescent children. Mental health intervention is not mandatory for young TGD children. Whether to seek mental health guidance is a decision typically made by caregivers, sometimes with strong recommendations from medical providers, teachers, or others. Assessment and therapeutic supports can be critical for many purposes, including advocacy and support for safety across environments; help in reducing family conflict and increasing family acceptance and positive communication; aid in strategizing whether and how to implement a social transition process (a process by which a child manifests changes in gender expression, including pronoun preferences, name changes, and so on); assistance with caregiver support and guidance; screening for mental health adjustment and risks in the child and other family members; increasing the child’s and family members’ gender-related knowledge and body literacy, including preparation for changes associated with puberty; decision making about potential medical interventions at the time of puberty and after; supporting the child and family members in developing positive coping strategies; and fostering resilience.

GENDER-AFFIRMING CARE FOR PEOPLE WHO INITIATE MEDICAL INTERVENTIONS DURING PUBERTY

Gender-affirming care for TGD people is multidisciplinary and includes both medical care and psychosocial support. In this section, the committee focuses on the medical care of TGD people who have delayed puberty through the use of GnRH analogs and/or received masculinizing or feminizing hormone therapy during puberty (i.e., during childhood and adolescence). The goal of these hormonal treatments is to align the physical characteristics of TGD youth with their gender identity. These medical interventions can help reduce gender dysphoria and improve quality of life for TGD people (Coleman et al., 2022; Van Der Miesen et al., 2020). However, medical interventions are not necessary for all TGD people (Coleman et al., 2022). Some TGD youth may be comfortable with their bodies or find other ways of expressing their authentic self and gender identity. Ideally, the decision to pursue medical interventions is made in consultation with a multidisciplinary team of health care professionals with expertise in gender-affirming care. Members of the health care team typically include adolescent medicine specialists, pediatric endocrinologists, behavioral health specialists, social workers, and nursing support staff (Coyne et al., 2023).

Gender-affirming medical care for TGD people should be patient centered, such that clinicians respect patients’ autonomy, preferences, values, dignity, individuality, and goals. Such standards are applicable to all health care situations. Patient-centered care is particularly important for gender-affirming care since, as discussed in Chapter 3, many TGD people experience barriers to care (e.g., difficulty locating care, disrespect, stigma in health care environments, discriminatory laws that prohibit gender-affirming care). The medical care of TGD people should be evidence based, culturally competent, and tailored to the individual needs and circumstances of each patient (Coleman et al., 2022; Salas-Humara et al., 2019).

With minors, psychologists, psychiatrists, and/or other behavioral health specialists are often asked to collaborate with patients and their families to aid in understanding their needs—which is necessary for making informed decisions about gender-affirming interventions (medical, psychosocial, or both)—and to facilitate access to these services. These clinicians also can aid in facilitating appropriate assent and consent processes1 to ensure that youth and their parents/caregivers understand the short- and long-term implications of treatment decisions, even when assent and consent are complex because of disabilities or other factors (Shumer and Tishelman, 2015). The SOC-8 strongly emphasizes the need for a process of biopsychosocial assessment and decision making prior to the initiation of gender-affirming medical care for adolescents; typically, this process will occur with a mental health provider trained in this type of assessment. Thus, the medical care of TGD people involves much more than gender-affirming hormonal and surgical interventions; clinicians also provide accurate information, offer emotional support, help with shared decision making, and coordinate care across different settings and disciplines.

For prepubescent children, hormone therapy, surgeries, and other treatment options described in this chapter are not appropriate (Hembree et al., 2017; Salas-Humara et al., 2019). For these young children, the only

___________________

1 Consent may only be given by individuals who have reached the legal age of consent (in the United States, this is typically age 18). “Assent” is an agreement by an individual who is not competent to give legally valid informed consent (e.g., a child aged 7–17 or cognitively impaired person). As part of the assent process, minors receive developmentally appropriate information about medical interventions to help them decide whether they want to take part. The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics (1995) describes appropriate assent as including the following: (1) Helping the patient achieve a developmentally appropriate awareness of the nature of their condition; (2) Telling the patient what he or she can expect with tests and treatment(s); and (3) Making a clinical assessment of the patient’s understanding of their condition and what, if any, outside factors may be influencing the patient’s response (including whether there is inappropriate pressure to accept treatment).

care choices are nonmedical and involve psychosocial interventions when needed, as described above (Coleman et al., 2022; Salas-Humara et al., 2019). For hormonal and surgical interventions, minors under age 18 provide assent and their parents or legal guardians provide consent before the intervention proceeds (Coleman et al., 2022; Salas-Humara et al., 2019). Individuals aged 18 and older can provide consent for hormonal and surgical interventions (Coleman et al., 2022; Salas-Humara et al., 2019).

Puberty-Delaying Medication

Puberty begins when increased GnRH is secreted from the hypothalamus, which causes the pituitary gland to secrete hormones known as gonadotropins (Abdel-Aziz et al., 2021). The gonadotropins cause the gonads (ovaries and testes) to produce the sex steroids estrogen and testosterone, respectively, which leads to the development of secondary sex characteristics. Puberty-delaying medications2 (also referred to as puberty blockers or puberty suppression) are GnRH analogs that act on the pituitary gland to prevent release of the gonadotropins, thereby forestalling the hormonal and physical changes of puberty (Salas-Humara et al., 2019). These medications have been used for many years to treat some forms of precocious (early) puberty and have been found to be safe and effective (Conn and Crowley, 1991; Martinerie et al., 2020). Importantly, use of these medications to treat these specific forms of precocious puberty does not cause infertility in adulthood (Kim, 2015).

When given early in puberty, GnRH analogs can ease “gender dysphoria”—the distress TGD adolescents may experience when their body does not align with their gender identity (Achille et al., 2020; Chakraborty et al., 2023; de Vries et al., 2011; Kuper et al., 2020; Van Der Miesen et al., 2020). Gender dysphoria can negatively affect adolescents’ general mental health, hamper their social development, and increase their vulnerability to self-harm and suicide (Marconi et al., 2023). By causing puberty delay, treatment with GnRH analogs may prevent these adverse outcomes, provide relief of psychological distress, and allow more time for psychosocial exploration of gender identity and expression (Achille et al., 2020; Allen et al., 2019). GnRH analogs prevent pubertal changes such as breast development and deepening of the voice, which are irreversible, thus alleviating dysphoria and reducing the need for future gender-affirming chest or voice

___________________

2 It should be noted that puberty delay as described in terms of gender-affirming care is not the same thing as “delayed puberty.” “Delayed puberty” is a medical condition in which puberty happens later than it is supposed to as part of a physical health condition. “Puberty-delaying medications” are used to pause puberty for adolescents who seek this intervention as part of gender-affirming care.

surgery (Patel et al., 2020; Van De Grift et al., 2020). GnRH analogs can also prevent menses, although this can also be achieved with other medications (Mauvais-Jarvis et al., 2013).3

Two medications are commonly used to suppress puberty: histrelin acetate (a long-acting, flexible rod inserted under the skin of the arm that typically lasts for 1–2 years) and leuprolide acetate (a long-acting injectable medication that typically lasts for 1, 3, or 4 months at a time) (Krebs et al., 2022). These medications are given only to children who have started puberty (i.e., have begun to undergo development of breast tissue or enlargement of the testes); puberty typically begins between ages 8 and 13 for children with ovaries and between ages 9 and 14 for children with testes. As with most other medical interventions for minors, puberty delay requires assent from the minor patient and consent from parents or guardians (Shumer and Tishelman, 2015).

Puberty-delaying medications are typically continued for a few months to several years, depending on an individual’s age and circumstances. This treatment provides time for youth and families to consider whether to initiate masculinizing or feminizing hormone therapy (with exogenous testosterone or estrogen, respectively), and if so, when (Guss and Gordon, 2022). Use of GnRH does not mean that gender diverse adolescents will subsequently start a course of hormone therapy: one study of 434 adolescents found that GnRH use did not increase the likelihood of subsequent use of gender-affirming hormones (Nos et al., 2022). However, findings are inconsistent, and some other research has demonstrated a high likelihood of adolescents continuing on to be prescribed gender-affirming hormones (Lee, 2023; Verroken et al., 2022).

The effects of puberty-delaying medications are generally reversible; if the youth stops taking them, puberty will resume within about 6 months (Salas-Humara et al., 2019). While physical changes may be reversible, however, there may be psychological or neurocognitive changes that are not reversible, and these important issues need additional investigation (Chen et al., 2020; Jorgensen et al., 2022). In addition, youth who began puberty-delaying medications early in puberty (e.g., Tanner Stage or sexual maturity rating 2) and who then initiate and remain on exogenous testosterone or estrogen will likely experience changes in fertility (discussed below) (Cheng et al., 2019).

Research is examining the associations between puberty-delaying medications and changes in bone density and neuronal maturation; both of these

___________________

3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises that hormone therapy for menstrual suppression is safe and effective in adolescent populations. According to ACOG (2022), there are many methods for achieving menstrual suppression, including “combined oral contraceptive pills, combined hormonal patches, vaginal rings, progestin-only pills, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device, and the etonogestrel implant” (p. 528).

potential associations are likely further modified by treatment with exogenous testosterone or estrogen (Ciancia et al., 2022; Van Der Loos et al., 2023). Additionally, for youth with a penis, puberty-delaying medications maintain the penis at its prepubertal size, leaving less available tissue for future vaginoplasty (Cheng et al., 2019). Any potential side effects should be carefully weighed against the benefits of alleviating and preventing gender dysphoria and improving mental health outcomes. Shared decision making by the youth, the parents (if the youth is younger than 18 years), and the health care team enables comprehensive discussions regarding the benefits and risks of specific treatment options (Mazzola et al., 2023).

Gender-Affirming Masculinizing or Feminizing Hormone Therapy during Puberty

Many, but certainly not all, TGD people initiate gender-affirming masculinizing or feminizing hormone therapy (Lane et al., 2022). Exogenously administered testosterone and estrogen help TGD people achieve, respectively, a more masculine or feminine appearance.

Testosterone

Testosterone induces changes in the body similar to those expected during typical male puberty, including increased growth of facial and body hair, deepening of the voice, and increased muscle mass and strength, as well as clitoral enlargement (Irwig, 2017; Yeung et al., 2019). The timeline for changes varies among patients, but most changes begin to take place within about 3–6 months of initiating the therapy and are fully realized after 2–5 years (Irwig, 2017). Clinicians should discuss with patients and families and monitor the potential side effects of testosterone therapy, such as increased risk of acne, male-pattern baldness (Yeung et al., 2019), increased cholesterol levels, and changes in sexual function. Testosterone also stimulates erythropoiesis, the production of red blood cells, and can unmask erythrocytosis (overproduction of red blood cells).

The most commonly used formulations of testosterone in the United States are testosterone enanthate (Delatestryl) and testosterone cypionate (Depo-Testosterone), which are injected intramuscularly or intradermally (Unger, 2016). Long-acting injectable testosterone formulations, implantable testosterone, buccal patches, and oral testosterone are available but less commonly used in the United States. Testosterone patches were discontinued in the United States in spring 2023 as they can cause contact dermatitis (itchy rash) which many patients found irritating (ASHP, 2023; Fleshner and Lawrentschuk, 2009). Testosterone gels are common but are more difficult to adjust in dose compared with other modalities (Unger, 2016). Testosterone may interact with other medications or supplements

an individual may be taking, but drug–drug interactions are rare (Moyer et al., 2019). Patients should be counseled that testosterone does not prevent pregnancy, even if they are not experiencing menstrual periods; thus, contraception should still be used for birth control (e.g., condoms; or long-acting reversible contraceptives such as an intrauterine device or etonogestrel implants, which can often further suppress menstruation) (Cheng et al., 2019).

Estrogen

Estrogen therapy and the suppression of testosterone induce changes similar to those expected during typical female puberty. Effects include growth of breast tissue and redistribution of fat to the buttocks and thighs (Patel et al., 2020). Lower levels of testosterone can also result in decreases in body hair, facial hair, muscle mass, acne, and balding. Decreases in spermatogenesis result in decreased testicular mass (Sinha et al., 2021). The timeline for changes varies among patients, but changes typically begin within about 3–6 months of initiating hormone therapy and continue for 2–5 years.

Estrogen therapy is associated with increased risk of blood clots (Abou-Ismail et al., 2020; Rosendaal et al., 2002). These side effects are not unique to TGD people, as cisgender people who take estrogen therapy experience these risks as well (Abou-Ismail et al., 2020; LaVasseur et al., 2022; Rozenberg et al., 2021). The most common forms of estrogen used in the United States are oral pills, injections, and transdermal patches (Safer and Tangpricha, 2019b). The choice of formulation depends on the individual’s preference, medical history, and other factors. Transdermal patches are associated with lower or no risk of blood clots but may be more expensive than other formulations (Abou-Ismail et al., 2020). Exogenous estrogen therapy does not typically interact with other medications or supplements an individual may be taking, although some binding proteins are increased that result in changes to some laboratory readings (Moyer et al., 2019).

Medical Monitoring

Given the changes and potential side effects that testosterone and estrogen can induce, individuals receiving GAHT should undergo regular monitoring, including blood work (Hembree et al., 2017). Youth who begin receiving estrogen or testosterone following pubertal delay should have their height and weight checked, ideally every 3 months, during the first year of treatment (Hembree et al., 2017). Hormone levels (i.e., testosterone or estradiol) should be monitored with blood testing to ensure adequate dosing and adherence to treatment; levels should be checked more frequently when

treatment is initiated or dose adjustments are made and can be checked less frequently once patients are on a stable regimen (Hembree et al., 2017). For patients on injectable formulations, interpretation of levels should be based on the timing of the most recent dose (i.e., peak, mid, or trough levels). At least yearly during adolescence, clinicians should order a complete metabolic panel, lipid panel, and hemoglobin A1C test; collectively, these assess renal function, liver function, cholesterol levels, and risk for diabetes (Hembree et al., 2017).

Dual X-ray absorptiometry scans should be performed to assess bone mineral density, especially among TGD youth using puberty-delaying medications without gender-affirming masculinizing or feminizing hormone therapy. Treatment with GnRH analogs followed by long-term gender-affirming masculinizing hormone therapy has been shown to be safe with respect to bone health in TGD people receiving testosterone (Ciancia et al., 2022); whether that is true for feminizing regimens remains to be established (Van Der Loos et al., 2023).

Fluidity of Gender Identity and Provider Response

Recent research has indicated that gender identity may evolve or be fluid for some adolescents (Katz-Wise et al., 2023a); thus, teens may experience shifts in needs and desires for medical interventions, with implications for a slower process of decision making for some (Cohen et al., 2023). Although understudied, some research also indicates that individuals may sometimes reflect upon the need or desire for continuing previously initiated GAHT, and mental health assistance may support individuals with decision making regarding care needs across time (MacKinnon et al., 2023).

Fertility Preservation

Before initiating gender-affirming hormone therapy, clinicians need to explain to youth and families that youth who receive puberty blockers followed by exogenous testosterone or estrogen may experience reduced fertility (Cheng et al., 2019; Choi and Kim, 2022). Specifically, puberty-delaying medications suppress germ cell maturation in ovaries and testes. Subsequently, sustained therapy with exogenous testosterone (in an individual with ovaries) prevents ovulation and menses, and sustained therapy with exogenous estrogen (in an individual with testes) prevents sperm development (Greenwald et al., 2021). Stimulated egg retrieval has been achieved in patients who started GnRH agonists early. In addition, in vitro fertilization (IVF) pregnancy has occurred with eggs retrieved from patients who did not stop testosterone (Greenwald et al., 2021). Thus, clinicians should present fertility preservation options to youth and their families, specifically

cryopreservation of ova and sperm. Ova and sperm can be retrieved once youth are midpuberty or at any time thereafter, and ideally before initiation of puberty-delaying medications (Choi and Kim, 2022). Fertility preservation may be possible for youth with ovaries who are prepubertal or in early puberty, but clinically available fertility preservation options for youth with testes do not exist unless spermatogenesis has occurred. Later in life, ova and sperm can be used for IVF (Choi and Kim, 2022). Individuals without a functional uterus typically require that a surrogate carrier with a functional uterus carry the pregnancy (Cheng et al., 2019).

Many clinicians refer youth and their families to an interdisciplinary fertility clinic that can offer integrated medical and psychosocial care. Limited access to and the cost of high-quality fertility services may be prohibitive for some families—such services are often not covered by health insurance—thus contributing to disparities in care.

Long-Term Follow-Up

During the initiation of GAHT, patients should return at least every 3 months for monitoring of their hormonal levels and assessment of whether treatment is meeting their goals (Hembree et al., 2017). After the first year of therapy, visits can be spaced to approximately every 6 months or even longer, provided that hormone treatment doses are stable, the therapy is meeting the patient’s goals, and the patient is not experiencing significant side effects or other complications. Ongoing support and care coordination from the clinician/health care team are beneficial, as gender-affirming care involves more than hormones. Thus, patients and their families should be supported in meeting with members of their health care team more frequently than every 6 months if requested. Additionally, when a multidisciplinary team is involved, and especially when care involves minors, patients may visit more frequently for psychosocial support and therapy, as well as coordination with medical intervention. More frequent visits can be particularly helpful for youth taking puberty-delaying medications who may need to decide whether and when to initiate gender-affirming masculinizing or feminizing hormone therapy, in collaboration with the team endocrinologist. Moreover, psychosocial support and therapy can benefit youth greatly in addressing social or emotional challenges that may arise. As discussed above, research indicates that it is not uncommon for adolescents’ gender identities to evolve over time (Cohen et al., 2023; Katz-Wise et al., 2023b), and gender-affirming mental health professionals can help youth and families, when appropriate, to consider their evolving gender-affirming care priorities as they develop.

GENDER-AFFIRMING MEDICAL CARE FOR PEOPLE WHO INITIATE GENDER-AFFIRMING HORMONE THERAPY AND OTHER CARE AFTER PUBERTY

Many TGD people do not seek gender-affirming medical care until after puberty. For some, this may be shortly after puberty is complete (which typically occurs in late adolescence or young adulthood and may occur before or after attaining the age of majority); others may access gender-affirming care later in life, long after puberty is complete. The reasons to wait to seek gender-affirming care until after puberty are varied: for some, postpubertal initiation of gender-affirming care reflects their personal choice, but others may lack information about possible interventions until adulthood, may not have the familial support and financial resources required, and/or may lack access to appropriate providers, all of which may prohibit initiation of gender-affirming care at an earlier stage (Puckett et al., 2018). Postpuberty, TGD people may seek any one of a number of gender-affirming interventions (as described further in this chapter), including GAHT. This section describes common GAHT regimens for these groups of TGD people, modifications to GAHT regimens to meet individual patient goals, and long-term follow-up for this patient population.

Gender-Affirming Masculinizing or Feminizing Hormone Therapy Postpuberty

As in the use of GAHT during puberty, the primary therapeutic goal for GAHT postpuberty is to allow for the acquisition of secondary sex characteristics (e.g., voice, facial hair, breast size, distribution of body fat and muscle) more aligned with an individual’s gender identity. For TGD people who seek gender-affirming medical care after puberty, masculinizing hormone therapy usually consists of exogenous testosterone to increase testosterone levels to the typical range of cisgender men (300–1,000 ng/dL). Feminizing hormone therapy usually consists of exogenous estrogen, along with other antiandrogens used adjunctively, to decrease testosterone to the typical range of cisgender women (<50 ng/dL). The literature describes commonly used masculinizing and femininizing hormone regimens, and these are presented briefly in the sections below (Ramsay and Safer, 2023; Safer and Tangpricha, 2019a,b). Boxes 5-1 and 5-2 display common GAHT regimens for TGD people that may be referred to in medical records.

Masculinizing Hormone Therapy

Both transgender men and other gender diverse individuals (including nonbinary and bigender people) may seek masculinizing hormone therapy

BOX 5-1

Common Masculinizing Hormone Therapy Regimens That May Be Referred to in Medical Records

Parenteral

- Testosterone ester (enanthate or cypionate)

- Testosterone undecanoate

Transdermal or transbuccal

- Testosterone gel

- Testosterone patch

- Testosterone buccal patch

Oral

- Testosterone undecanoate

SOURCE: Safer and Tangpricha, 2019b.

with the goal of developing typical male secondary sex characteristics, while minimizing sex characteristics typically associated with females. The use of GAHT in these populations is very similar to the hormone replacement therapy that cisgender men may need for hypogonadism (where the testes produce little or no hormones),4 with some dosing modifications.

As shown in Box 5-1, testosterone can be administered orally, transdermally, or parenterally, and regimens consist of gels, patches, injectable esters, and long-acting implanted testosterone (Barbonetti et al., 2020; Ramsay and Safer, 2023). Exogenous testosterone preparations currently used in the United States are chemically equivalent to the testosterone secreted from human testes (Barbonetti et al., 2020; Shoskes et al., 2016). The most popular formulation is a testosterone ester (enanthate or cypionate) 50–200 mg weekly administered intramuscularly or subcutaneously (Safer and Tangpricha, 2019b; Spratt et al., 2017), although some patients may prefer higher doses (100–200 mg) administered less frequently. Transdermal testosterone gel (2.5–10 g/day) can achieve the same virilizing effects as injection testosterone, but poor absorption may prove frustrating, especially to larger patients (Safer and Tangpricha, 2019a). Although not widely used,

___________________

4 “Hypogonadism” occurs when the body’s sex glands (the testes or ovaries) produce little or no hormones. Some types of hypogonadism can be treated with hormone replacement therapy (Kumar et al., 2010).

oral testosterone undecanoate (160–240 mg/day), long-acting implanted testosterone pellets, and long-acting injectable testosterone are also available (Safer and Tangpricha, 2019b). There is no indication for adjunct antiestrogens therapy.

Over the first 3–12 months, response to testosterone treatment may include increased facial/body hair, male-pattern balding, increased acne, increased libido, increased muscle mass, clitoromegaly, deepening of the voice, and redistribution of fat (Safer and Tangpricha, 2019b). Menses cease in most individuals within 6 months of starting treatment.

Feminizing Hormone Therapy

Both transgender women and other gender diverse individuals (including nonbinary and bigender people) may seek femininizing hormone therapy with the goal of developing typical female secondary sex characteristics, while minimizing sex characteristics typically associated with males. Commonly used exogenous estradiol can suppress testosterone levels via central feedback while avoiding hypogonadism. The use of GAHT in these populations is similar to hormone replacement therapy that cisgender women use to treat menopausal symptoms, with some dosing modifications (Safer and Tangpricha 2019a; Vigneswaran and Hamoda, 2022).

Like testosterones, estrogens can be administered orally, transdermally, or parenterally, as shown in Box 5-2. The primary class of exogenous estrogen used in feminizing hormone therapy, 17-beta estradiol, is chemically identical to estradiol, a naturally occurring hormone produced by the ovaries. Oral 17-beta estradiol (2–10 mg) daily is a popular regimen because it is easy to use and readily available. Also, 17-beta estradiol can be delivered via transdermal patch. Data suggest that this approach may reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism (blood clots) associated with exogenous estradiol use,5 and WPATH guidelines recommend transdermal estradiol in doses up to 100 mcg/daily for individuals aged 45 and older (Coleman et al., 2022). In addition, estradiol can be administered orally as conjugated estrogens (2.5–7.5 mg) or parenterally as estradiol valerate or cypionate (5–20 mg intramuscularly every 2 weeks or 2–10 mg intramuscularly every week). Each formulation may result in metabolites that can confound the measurement of hormone levels. Ethinyl estradiol should be

___________________

5 There may be a slightly elevated potential for venous thromboembolism with exogenous estrogens. The risk is relatively low with estrogens in current use for TGD people. Therefore, for transgender women and nonbinary individuals seeking feminizing hormone treatment with a history of venous thromboembolism, it may be most effective to maintain the hormone treatment regimen and to follow prophylaxis protocols (Abou-Ismail et al., 2020).

BOX 5-2

Common Feminizing Hormone Therapy Regimens That May Be Referred to in Medical Records

Estrogens

Oral

- Estradiol (17-beta estradiol)

- Conjugated estrogens

Transdermal

- Estradiol patch

Parenteral

- Estradiol valerate

Androgen-lowering or inhibiting agents

Spironolactone

Cyproterone acetate

gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (e.g., leuprolide)

SOURCE: Safer and Tangpricha, 2019b.

avoided because of its increased risk of venous thromboembolism (Hembree et al., 2017; Safer and Tangpricha, 2019b).

Incorporating in the hormone regimen an adjunctive antiandrogen (which suppresses testosterone) is thought to allow for lower doses of estrogen, decreasing the dose-related risk of venous thromboembolism. Spironolactone—an aldosterone receptor antagonist that can also inhibit the secretion of testosterone—is the most commonly prescribed adjunct antiandrogen agent because it is the least costly (Ramsay and Safer, 2023). Spironolactone is typically administered to TGD people in doses of 100–200 mg daily. GnRH analogs, such as leuprolide (3.75 mg administered subcutaneously monthly), are another common androgen-lowering agent, working to inhibit the production of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, and therefore testosterone (Ramsay and Safer, 2023). GnRH analogs are the preferred adjunct to estrogens in the United Kingdom, but they are more expensive than spironolactone and must be given by injection. Cyproterone acetate, a progestin, was historically the most popular adjunct gender-affirming hormone treatment in Continental Europe (although not available in the United States). However, side effects associated with cyproterone acetate—including elevations in prolactin

levels (the hormone that enables breast milk production), worsening of lipid profiles, and rare meningioma (benign brain tumor) growth—have all served to decrease its popularity (Burinkul et al., 2021; Hage et al., 2022). Nonetheless, these adjunctive antiandrogens may still be in use by some patients and could be listed in medical records.

In the first 3–12 months of feminizing hormone therapy, patients should expect decreased rate of growth of facial/body hair, decreased libido, decreased spontaneous erections, decreased skin oiliness, decreased muscle mass, redistribution of fat, and breast development. Breast growth may continue for the first 2 years of therapy.

Lower-Dose Regimens

Some patients may request treatment with lower doses of testosterone or estrogens than would be needed to achieve typical male or female hormone levels; some patients term this “microdosing.” The cautions with lower-dose regimens are twofold. First, in patients who do not have endogenous hormone production, exogenous hormone doses should not be so low that they are insufficiently protective of bone density (Safer and Tangpricha, 2019a). However, if there is sufficient sex hormone circulating (testosterone and estrogens combined), there is no medical reason to favor a hormone profile that is more typically female, versus one that is more typically male, versus one that is along the continuum in between. Second, even lower hormone therapy doses can have dramatic physical consequences for some people, and patients who seek lower-dose regimens should be aware that they may be more sensitive than anticipated and may have irreversible physical responses (e.g., more significant than expected beard growth and voice lowering from testosterone, more significant than expected breast growth from estrogen-induced testosterone lowering). Patients should be counseled accordingly, with a review of their specific needs and goals before treatment begins.

Both patients who have a binary identity (e.g., as transgender men or transgender women) and patients who identify as nonbinary or bigender may seek lower-dose hormone treatments. Also, TGD patients, regardless of terms used to describe themselves, may seek conventional binary hormone regimens. Thus, it is important to determine independently both a patient’s self-identified gender identity and a patient’s hormone regimen.

Additional Hormone Regimens

The WPATH Standards of Care (Coleman et al., 2022) and such practice guidelines as the Endocrine Society of North America’s Guidelines for Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons

(Hembree et al., 2017) reflect recommended and commonly used practices, as described above. However, not all hormone regimens used by TGD patients are accounted for in these evidence-based guidelines—for example, because of a lack of efficacy data, insufficient data in TGD populations, or safety concerns. However, TGD people may access various alternative hormone regimens, as may be reflected in medical records.

Additional Approaches to Administering Masculinizing Hormone Therapy

These approaches include testosterone pellets, testosterone nasal spray, and oral testosterone undecanoate. None of these are known to be superior to the more popular injectable testosterone esters and topical testosterone gel. Concerns with the nasal spray relate to the irritation observed with other nasal spray products with other active ingredients (Acerus Pharmaceuticals Corporation, 2016). Testosterone pellets are typically reserved for people who already have an established dose because titrating pellets (especially down-titrating) can be a challenge.

Additional Approaches to Administering Feminizing Hormone Therapy

These approaches include sublingual estradiol (Doll et al., 2022; Sarvaideo et al., 2022) and estrogen pellets. Sublingual estradiol can result in higher peak levels followed by lower trough levels (Doll et al., 2022), with unknown benefits or detriments. For those patients concerned with thrombolytic events, sublingual estradiol may be useful because it avoids a first pass through the liver. Alternatively, if the major cause for increased thromboembolic risk with exogenous estrogens is associated with the total dose received, sublingual estradiol may best be avoided (Doll et al., 2020). Estrogen pellets are typically reserved for people who already have an established dose because, as noted above, titrating pellets (especially down-titrating) can be a challenge.

Additional Approaches to Androgen-Suppressing Medications

These approaches may include bicalutamide (Neyman et al., 2019; Wilde et al., 2024), dutasteride (Gao et al., 2023), and flutamide. Bicalutamide has gained interest because it is inexpensive, and it blocks the androgen receptor. However, bicalutamide has been associated with a small number of cases of fulminant hepatitis and death (O’Bryant et al., 2008; Wilde et al., 2024; Yun et al., 2016). Although rare, cases of hepatitis and death came without warning and were not dose related; currently, there are no options for monitoring these risks. Therefore, the WPATH SOC-8 guidelines note that the use of bicalutamide is not recommended (Coleman et al., 2022).

Progesterone

Available medications for administration of progesterone include medroxyprogesterone acetate and micronized progesterone (Bahr et al., 2024). There are no quality data demonstrating any benefit from progestogens used in gender-affirming hormone treatment. All data on progestogens to date show harm with agents used over many years (Coleman et al., 2022). Specifically, medroxyprogesterone is associated with increased breast cancer and increased heart disease in postmenopausal cisgender women (Chlebowski et al., 2020; Rossouw et al., 2002). A range of progestogens are associated with increased thromboembolic risk when combined with estrogens (the most common examples being birth control pills for cisgender women) (Dragoman et al., 2018). Cyproterone acetate has been associated with worse lipid profile, slight prolactin elevation, and a small increased risk of meningiomas in transfeminine people (Millward et al., 2022).

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators

These agents, such as tamoxifen, raloxifene, and lasofoxifene, also known as estrogen receptor agonists/antagonists, have different effects in various tissues (Xu et al., 2021). These medications have been proposed for TGD people who want some of the effects of estrogens, such as softer skin and a gynoid fat distribution, but not others, such as breast growth (Xu et al., 2021). There are no data showing the efficacy of these agents and no data to support the risks of heart disease, bone harm, or hot flash symptoms (depending on the agent chosen) outside of indicated uses (e.g., for breast cancer).

Minoxidil

Topical minoxidil has been used off-label to facilitate facial hair growth in transgender men whose response to testosterone has been limited (Pang et al., 2021). Oral minoxidil has been used off-label to treat androgenetic hair loss in TGD people exposed to higher levels of testosterone either endogenously from testicular production or exogenously as part of masculinizing hormone therapy (Motosko and Tosti, 2021).

Fertility and Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy

GAHT may reduce fertility, but does not necessarily eliminate it (Amato, 2016). TGD people on testosterone have reduced fertility, but if a uterus and ovaries are still present, pregnancies can occur. Similarly, estrogen and

antiandrogens can cause diminished spermatogenesis and testicular atrophy (Cheng et al., 2019). Because ovulation and spermatogenesis may continue in the presence of hormone therapy, all TGD people who engage in sexual activity that could result in pregnancy should be counseled on the need for contraception (Amato, 2016).

GAHT likely affects fertility only temporarily (Coleman et al., 2022), although infertility can be permanent (Amato, 2016). The extent to which fertility can return is unresearched, but some TGD people do reproduce (Keuroghlian et al., 2022; Light et al., 2014; Thornton and Mattatall, 2021). Some transgender men may wish to carry a pregnancy and stop using testosterone to facilitate doing so safely; anecdotally, fertility may return 3–6 months after cessation of GAHT (Amato, 2016). Transgender women may wish to use their sperm for pregnancy and can often do so after stopping GAHT.

However, gender-affirming surgeries that remove the gonads (ovaries or testes) result in infertility, as does hysterectomy. Guidelines recommend thorough counseling with a patient who wishes to undergo gonadectomy (Amato, 2016). Fertility preservation options for storing eggs or sperm allow for future reproductive choices (Cheng et al., 2019).

Long-Term Follow-Up

It is important to monitor hormone levels in patients receiving GAHT to ensure that levels reach the target range for specific patients. Guidelines suggest monitoring hormone levels in transgender patients with each adjustment in hormone dose (approximately every 3 months during the first year) and once or twice yearly after target levels have been achieved, or whenever the dose is changed (Hembree et al., 2017; Safer and Tangpricha, 2019b).

In addition, long-term follow-up of patients on GAHT includes monitoring other factors, as transgender men and nonbinary individuals who access GAHT may have a risk of erythrocytosis (high concentration of red blood cells), and transgender women and nonbinary individuals may have an increased risk of blood clots while on GAHT (Ramsay and Safer, 2023). Because androgens are known to stimulate erythrocytosis, hematocrit (or hemoglobin) levels in transgender men and nonbinary individuals should be monitored with dose titration, typically every 3 months, and once or twice annually thereafter (Madsen et al., 2021; Ramsay and Safer, 2023). Dose adjustment and/or other interventions, such as phlebotomy, may be required if erythrocytosis is unmasked and a reversible explanation (e.g., hypoxia, obstructive sleep apnea, polycythemia rubra vera, renal cell carcinoma) is not found. For transgender women and nonbinary individuals who receive spironolactone, routine monitoring of serum potassium is advised because of the potential risk of hyperkalemia (high potassium); serum potassium

levels should be checked upon initiation of spironolactone therapy and with changes in dose (often with titration every 3 months until steady-state hormone levels have been achieved). Although some guidelines still suggest monitoring serum prolactin levels, elevated prolactin levels have been noted only in patients using adjunct cyproterone acetate, not in those using other adjunct treatments or in those using estrogens alone (Bisson et al., 2018).

In addition, testing of bone mineral density may be important for TGD patients who have had prolonged periods of hypogonadism or have other risk factors for osteoporosis. Overall, there is no evidence of major bone loss with GAHT (Verroken et al., 2022), and bone mineral density may increase for TGD people using testosterone (Radix et al., 2016; Stevenson and Tangpricha, 2019). Medicare data show lower rates of osteoporosis in TGD (8.2 percent) than in cisgender (15.7 percent) people (Dragon et al., 2017). There are no consistent guidelines for optimal frequency of bone density screening for cisgender people, and there is not enough evidence to guide recommendations on bone density testing for TGD adults (Radix et al., 2016).

Routine cancer screening is important for TGD patients in accordance with guidelines established for the general population, but screening should be performed on the tissues and organs present, not those related to gender identity or sex as recorded in the medical record. Additional considerations for cancer screening in TGD people are discussed below.

Finally, and importantly, providers should monitor patients to determine the need for mental health support. Psychosocial supports are described in further detail below.

GENDER-AFFIRMING SURGERY AND POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Gender-affirming surgery comprises a constellation of medically necessary procedures intended to align people’s bodies with their identity. While some TGD people do not undergo gender-affirming surgery, such surgery is considered safe and effective and results in reduced gender dysphoria and improved quality of life (Almazan and Keuroghlian, 2021; Coleman et al., 2022; Departmental Appeals Board, 2014). The decision to pursue the surgery today is based on a thoughtful and multidisciplinary evaluation following WPATH’s SOC-8 (Coleman et al., 2022). This evaluation allows for an individualized approach using shared decision making to optimize preparedness for surgical interventions.

This section examines preoperative preparation and assessment, describes surgical aftercare, and details common surgical procedures (including facial surgery, breast surgery, chest surgery, vaginoplasty, metoidioplasty, and phalloplasty). The section ends with a discussion of considerations for customizing gender-affirming surgery for individual patients.

Preoperative Preparation and Assessment

The WPATH SOC-8 guidelines offer best practices for providing evidence-based care to TGD people. The overarching goal for gender-affirming care—including surgical interventions—is to maximize overall health, psychological well-being, and self-fulfillment (Coleman et al., 2022). For this reason, surgical care for gender dysphoria is best approached with a multidisciplinary team. The diagnosis of gender dysphoria is generally made by mental health providers or primary care professionals with expertise in TGD health. These providers then refer appropriate candidates for gender-affirming surgery. Communication between the surgeon and mental health and primary care professionals helps the surgeon understand the unique needs of each individual. Discussion with other treating medical providers (endocrinologists, allied health practitioners, and other surgeons) can also provide insight into the patient’s goals. Open dialogue should extend beyond the preoperative period; the surgeon should relay information regarding surgical findings and postoperative care to relevant members of the health care team (Schechter, 2009). In recent years, the multidisciplinary care team has expanded to include other disciplines, such as physical therapy for pelvic health, sex therapy, and voice therapy. This comprehensive approach helps individuals realize the optimal positive impact of the surgery.

While preoperative mental health evaluation has historically been criticized for “gate-keeping” access to gender-affirming surgery, the current role of mental health professionals has evolved. Mental health professionals can help individuals with decision making about surgical and other care options, provide counseling on reproductive and sexual goals, and collaborate with surgeons to provide counseling in preparation for surgery. In addition, mental health professionals can help prepare a patient for surgery and postoperative life by identifying and building support systems and by informing expectations regarding the impact of the surgery on other aspects of life (e.g., family, friends, intimate relationships, work) (Roblee et al., 2023). The importance of evaluating and addressing psychosocial needs is seen in other fields, such as organ transplantation, in which poor social support and other vulnerabilities are associated with less favorable outcomes (Maldonado, 2019). Additionally, preoperative assessment of psychosocial measures strengthens the informed-consent process by helping individuals understand and internalize the expected effects of surgery.

Aftercare

Development of an aftercare plan prior to surgery not only facilitates care coordination but also helps optimize surgical outcomes (Roblee et al., 2023). Social workers and/or care navigators can work with patients to assemble a detailed aftercare plan, which includes identifying physical, mental, social, and financial resources, as well as surgical follow-up. For example, social workers

might verify local lodging after discharge to allow for follow-up care (especially if a patient is traveling from out of town), confirm social support during the postoperative period, and verify that travel logistics have been arranged (Coleman et al., 2022).

Surgical Procedures

Surgery for TGD people includes several options and may involve procedures to enlarge, reduce, or remove the breasts, various genital surgeries, and facial or other body-contouring procedures to create a more feminine or masculine appearance. Facial and breast surgeries may sometimes be performed prior to GAHT as a way to facilitate social transition (Altman, 2021; Davis and St. Amand, 2014; Olson-Kennedy et al., 2018; Van Boerum et al., 2019).

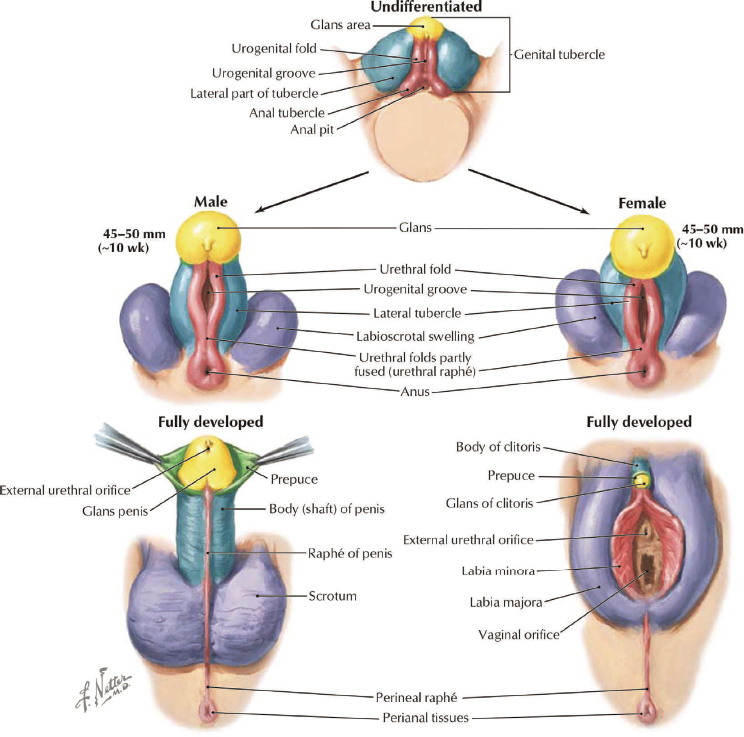

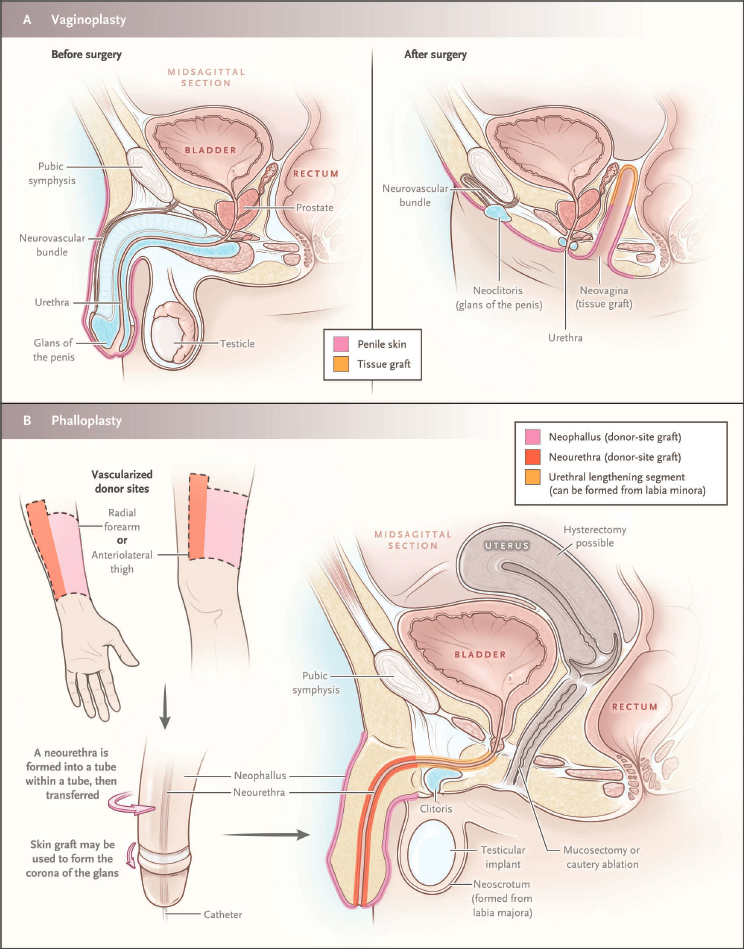

The principles of gender-affirming genital surgery are based on anatomy and embryology. The external genitalia are homologous structures (there is a corresponding anatomic part in each of the biological sexes), and the corresponding anatomic tissues are used to create the relevant anatomy. Figure 5-1 illustrates the embryology of the external genitalia, while Figure 5-2 shows the anatomy of common approaches to gender-affirming surgery. In vaginoplasty procedures, the glans clitoris is formed from the glans penis, the labia majora are formed from the scrotum, and the penile urethra is shortened to form the urethra and vestibule. Conversely, in a phalloplasty, the clitoro-vulvar anatomy is reconfigured, and additional tissues are used to reconstruct the penis; the perineal and penile urethra; and the scrotum, constructed from the labia majora.

The relationship between GAHT, especially estrogen, and the risk of perioperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) following gender-affirming surgery continues to evolve. Historically, surgeons discontinued GAHT in the perioperative period to decrease the risk of VTE (Hontscharuk et al., 2021). However, abrupt cessation of GAHT may negatively affect well-being (Hontscharuk et al., 2021). While additional research on mitigating the risk of VTE in gender-affirming surgical care is needed, recent research has not found significant risk of perioperative VTE in TGD people on estrogen therapy (Kozato et al., 2021), and current evidence does not support routine discontinuation of GAHT prior to surgery for all patients (Boskey et al., 2019).

The subsections below provide a brief description of facial, breast, chest, and genital gender-affirming surgical procedures.

Facial Surgery

Facial surgery can be feminizing or masculinizing. Feminizing procedures often focus on areas of the forehead, nose, malar region, mandible, and thyroid cartilage. For example, brow lift with advancement of the frontal hairline and frontal bone reduction is frequently performed. A feminizing rhinoplasty can involve dorsal hump reduction, cephalic trim, elevation of

NOTE: The male and female external genitalia are considered homologous structures; that is, there is a corresponding anatomic part in each of the biological sexes. In transgender females who receive gender-affirming surgery, the component parts of the typical male anatomy are reassembled to construct the relevant typical female anatomy. Conversely, in transgender males, the typical female anatomy is removed and reassembled to construct portions of the typical male anatomy.

SOURCE: Schechter, 2016. Used with permission of Elsevier; from Surgical management of the transgender patient, 1st Edition, Copyright © 2016: permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

NOTE: The term “mucosectomy” used in the figure in reference to ablation of the vaginal lining is not correct. The vaginal lining is epithelium (not mucus membrane).

SOURCE: Safer and Tangpricha, 2019b. From New England Journal of Medicine, Care of Transgender Persons, 381(25):2451–2460 Copyright © 2018 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

the nasal tip, and osteotomies to narrow the nasal pyramid. Feminization of the chin and mandible often involves an osteoplastic genioplasty and mandibular angle reduction. Reduction thyroid chondroplasty can reduce the appearance of the “Adam’s apple.” Nonsurgical interventions, such as lipofilling (or “fat grafting”), injectable fillers, and hair transplantation or removal, may be performed as well.

Masculinizing facial procedures include chin and mandibular angle implants and/or augmentation of the thyroid cartilage to create a more prominent “Adam’s apple” (Safa et al., 2019). This continues to be an emerging area of surgery, although the techniques for developing masculine facial features have been adapted from other types of facial plastic surgery procedures (Deschamps-Braly et al., 2017).

Breast Surgery

While estrogen hormone therapy results in some breast growth, the degree of breast growth is often limited and may be highly variable (de Blok et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2021). Additionally, the breast growth is frequently similar to a “tuberous” breast (where breasts do not have a round shape) and may consist of a constricted lower pole and “herniation” of breast tissue beneath the nipple-areola complex. Because these results can be disappointing, breast augmentation is commonly pursued among transgender women to achieve a more feminine appearance (Patel et al., 2021).

A person whose sex at birth was recorded as male and who has undergone an androgen puberty (e.g., a person who did not access pubertal delay and GAHT during puberty) typically has a wider chest than that of a person whose sex was recorded as female at birth. The nipple-areola complex is smaller, the distance between the nipple and the inframammary crease is shorter, and the pectoral muscle is larger. Because of these anatomic differences, a wider implant is commonly chosen. Location and incision choice depend on the individual, but a sublandular, subfacial, or subpectoral pocket may be used, and the inframammary crease incision is most commonly chosen (Brown et al., 2021).

Pre- and postoperative breast cancer screening guidelines depend upon age, family history, genetic risk, duration of hormone use, and physical examination (Claes et al., 2018).

Chest Surgery

Chest masculinization surgery is the most commonly requested masculinizing gender-affirming surgery. Goals of chest surgery include removing breast tissue and excess skin, reducing and repositioning the nipple-areola complex, releasing the inframammary crease, and minimizing chest scars

(Monstrey et al., 2008).6 Choice of incision depends on breast volume, degree of breast ptosis (sagging of the breasts), nipple-areola size and position, amount of excess skin, and skin elasticity. A periareolar incision may be adequate for small breasts with good skin elasticity and without ptosis, whereas larger breasts often require the traditional “double incision” (i.e., transverse incision along the origin of the pectoral muscle) with nipple-areola grafts. Liposuction may be a useful adjunct to further contour the chest. Drains and elastic compression are used in the postoperative period (Brown et al., 2021).

Vaginoplasty

The use of pedicled penile flaps was described more than 40 years ago and serves as the foundation for feminizing genital surgery (Hage et al., 2007; Hontscharuk et al., 2021). Surgical options for vaginoplasty include penile inversion vaginoplasty, intestinal vaginoplasty, and/or peritoneal flaps. Penile inversion vaginoplasty is most commonly performed for primary surgery, while other techniques are used in revisions or in cases involving inadequate penile tissue. Penile inversion vaginoplasty uses an anterior pedicled penile skin flap combined with a scrotal skin graft. Prior to surgery, removal of hair on the scrotum and penile shaft is recommended to reduce intravaginal hair growth. The vaginoplasty procedure requires lifelong vaginal dilation to maintain vaginal depth and width. Intestinal vaginoplasty, typically using the sigmoid colon, creates a 12–15 cm vagina with moist lining due to mucus production from goblet cells. This procedure requires intra-abdominal surgery with a bowel anastomosis. While the intestinal approach may lessen the need for vaginal dilation and lubrication, significant discharge may require use of a pad in the underwear. Nongenital flaps (i.e., peritoneum) may also be employed. In these cases, the peritoneal lining is advanced to form the apex of the vaginal canal.

Additional options include vulvoplasty (construction of clitorovulvar structures) without creation of a vaginal canal. This surgery may be performed in individuals who do not anticipate receptive vaginal intercourse, are unable or do not want to dilate the vaginal canal or have medical

___________________

6 While chest masculinization is very similar to mastectomy, the goals are different. Mastectomy is most often performed as part of breast cancer treatment or prevention and involves removal of the entire breast (and sometimes other nearby tissues, such as lymph nodes). The goal of chest masculinization surgery is to shape the skin and tissue of the chest to match the contour of a male chest; residual breast tissue (used to aid in masculine chest contour) may remain and, for this reason, individuals may continue to carry risk for breast cancer.

contraindications to construction of the vaginal canal (i.e., previous pelvic surgery and/or radiation).

Following vaginoplasty, in addition to dilation of the surgically created vaginal canal, vaginal rinsing (or “douching”) is also recommended to cleanse the canal, as desquamated skin or mucus secretions may be retained.

Metoidioplasty and Phalloplasty

Masculinizing genital surgery requires understanding the goals of the individual, as reconstruction may or may not include urethral reconstruction, colpectomy/colpocleisis, and various flap options. Surgery may range from clitoral release (metoidioplasty) with or without urethral lengthening (to allow for voiding while standing) to phalloplasty, which allows for sexual penetration following placement of implantable penile prostheses.

Metoidioplasty, first described by Hage (1996), involves lengthening the hormonally hypertrophied clitoris by releasing the suspensory ligament, resecting the ventral chordee, and lengthening the urethra (see also Heston et al., 2019). Hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and colpectomy with colpocleisis may also be performed. Scrotoplasty and testicular implants are often performed in a secondary surgical procedure to reduce the risk of infection and wound-healing complications (Kocjancic and Iacovelli, 2018).

Phalloplasty techniques include pedicled flaps and free flaps. Pedicled flaps transfer tissue from the thigh, groin, or lower abdomen, whereas free flaps involve microsurgical transfer of tissue from a remote location, typically the forearm. The radial forearm free flap is the most common technique used for phalloplasty (Gottlieb, 2018; Schechter and Facque, 2021). This procedure transfers tissue, including blood vessels and nerves, from the forearm to reconstruct a sensate phallus and urethra, when requested. Drawbacks of the forearm procedure include the visibility of the donor site and the need for microsurgical skills. The second most common technique entails use of tissue from the thigh, known as the anterolateral thigh flap (Schechter and Facque, 2021; Xu and Watt, 2018). In some cases, however, thick subcutaneous thigh tissue may preclude this technique. In both the anterolateral thigh flap and the radial forearm free flap, the urethra is formed by a skin-lined tube; as a result, preoperative electrolysis may be required for hair removal.

Following phalloplasty, an implantable penile prosthesis may be placed to achieve rigidity and allow for penetrative intercourse. The metoidioplasty does not create a phallus of sufficient dimensions to allow placement of a prosthesis. Testicular implants may be placed in a surgically created scrotal sac following either metoidioplasty or phalloplasty.

Complications following metoidioplasty/phalloplasty are not uncommon and can include urethral problems (e.g., stricture, fistula) and wound-healing complications (Nikolavsky et al., 2018). Lifelong urological follow-up is recommended following the surgery (Coleman et al., 2022).

Individually Customized Surgery

TGD people, particularly those who self-identify as nonbinary, may have surgical goals and expectations that differ from the more binary options reviewed above. Therefore, gender-affirming surgical procedures need to be individualized (Schechter and Facque, 2021). For example, patients may opt for phallus-preserving vaginoplasty, vagina-preserving phalloplasty, penile subincision, or penile bisection (Chen et al., 2021; Salgado et al., 2021).

As with all individuals considering surgery, the patient and multidisciplinary team need to work together in a shared decision making process to ensure that the patient’s goals are realistic and achievable, as well as safe and technically feasible (Coleman et al., 2022). In addition, the medical record should clearly document surgeries undertaken and organs that are still present.

Sexual Function Postsurgery

Sexual function is an important consideration for many people undergoing genital gender-affirming surgery, and preoperative sexual function tends to correlate with postoperative sexual function. Studies of sexual function following masculinizing genital surgery (metoidioplasty and phalloplasty) report high sexual function satisfaction: one study found that 87.63 percent of patients surveyed were satisfied with overall sexual function (Vukadinovic et al., 2014). Other studies have found similarly high rates of retained sexual function among transgender males (Garcia et al., 2014; Van de Grift et al., 2019). Vaginoplasty results in similar levels of high satisfaction among transgender females (Hadj-Moussa et al., 2018; Holmberg et al., 2019; Horbach et al., 2015; Zavlin et al., 2018). In a study of patients years after vaginoplasty, sexual satisfaction was related to neoclitoral sensitivity, and less to vaginal sensitivity or depth (Jerome et al., 2022).

Complications following surgery may impair sexual function. Lack of erogenous sensation and complications with prosthetics (required for the phallus to achieve rigidity) have been reported among transgender males (Elfering et al., 2021; Khorrami et al., 2022). Complications regarding prosthetics (malfunction, extrusion, infection, dislodgement) are not uncommon.

Among transgender females, a small percentage of patients (2–6 percent) report painful intercourse (dyspareunia) (Horbach et al., 2015).

NONMEDICAL MODALITIES

Gender-affirming interventions may include nonmedical modalities that can have an impact on physical health, including important implications for disability evaluations. These interventions include binding, tucking, packing, and non–medically supervised injection of soft-tissue fillers. These interventions may be used on their own or in combination with GAHT and/or surgery, depending on individual patient preference.

Binding

Transgender males and nonbinary people whose sex was recorded female at birth may choose to bind the breasts (including with commercial binders or by wearing one or more sports bras, tape, cloth, plastic wrap or elastic bandages) to create a flat and more masculine appearance (Coleman et al., 2022). Chest binding is associated with reduced chest dysphoria, improved mental health outcomes, and increased sense of safety in public, and may be undertaken prior to or in lieu of gender-affirming chest reconstruction surgery (Lee et al., 2019; Peitzmeier et al., 2017). Many individuals who bind do so daily and for extended periods of time, often exceeding 10 hours each day (Julian et al., 2021; Peitzmeier et al., 2017). Adverse effects associated with binding in a large cross-sectional survey included pain (back, chest, shoulder, and abdominal) (74 percent); skin and soft-tissue complaints, including tenderness, skin infection, scarring, and itching (76.3 percent); shortness of breath (46.6 percent); and lightheadedness or dizziness (27.8 percent). Musculoskeletal changes related to binding may include muscle wasting (5.4 percent), rib fractures (2.8 percent), or other rib/spine changes (11.6 percent) (Peitzmeier et al., 2017).

Chest binding may impact spirometry testing. In a small study of TGD people, wearing a binder reduced chest circumference and resulted in significant declines in forced vital capacity and slow vital capacity compared with not wearing a binder (Cumming et al., 2016). Chapter 8 describes respiratory health, spirometry measurement, and chest binding in greater detail.

Tucking

Tucking refers to the process of creating a flat appearance by compressing or hiding the external genitalia in transgender females and nonbinary

people whose sex was recorded male at birth. One study of transgender female adults found that most (74.4 percent) practiced tucking, with the majority of those practicing tucking (84.5 percent) doing so daily (Malik et al., 2024). This process includes positioning the testicles close to or through the inguinal canal and tucking the penis back between the buttocks, usually accompanied by wearing a compressive undergarment (called a gaff), tape, or tight padded or layered underwear. Tucking may cause skin and soft-tissue conditions (itching, rash, fungal infections) (Huang et al., 2022), impaired semen quality, pain, and testicular torsion (de Nie et al., 2022; Debarbo, 2020; Williamson, 2010).

Packing

Transgender males and nonbinary people whose sex was recorded female at birth may use padding or a penile prosthesis (“packer”) to create a genital bulge. Packers can be soft or firm and are held in place with a harness or tight undergarments or skin adhesive. Some packers may allow the individual to urinate while standing (“stand-to-pee” packer). Packers may be associated with skin irritation and excoriation (Huang et al., 2022; Williamson, 2010).

Silicone

Transgender females and nonbinary people whose sex was recorded male at birth may inject soft-tissue fillers, including free silicone, into the breasts, buttocks, and hips to create a more feminine appearance. This process can result in migration of silicone and pigment changes (Bertin et al., 2019; Soliman, 2023), skin and soft tissue infection (Bertin et al., 2019), granulomas (Ohnona et al., 2016; Pando et al., 2022), hypercalcemia (Pando et al., 2022), chronic ulceration (Soliman, 2023), immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (van der Pluijm et al., 2022), pneumonitis, and alveolar hemorrhage (Bejarano et al., 2020). It may also lead to concerns about bloodborne pathogens, such as HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C, due to sharing of needles.

CANCER SCREENING CONSIDERATIONS

As noted earlier, patients should in general be screened for cancers in the tissues they have present, rather than being screened based on data on sex or gender identity recorded in medical records. TGD people who have accessed gender-affirming care interventions—including GAHT, gender-affirming surgery, and nonmedical modalities—may require modifications to

routine preventive cancer screenings. This section describes considerations for screening for breast, prostate, and cervical cancer. Additional considerations for TGD people who have prostate or cervical cancer or other cancers of the reproductive system are described in Chapter 11 of this report.

Breast Cancer Screening