Sex and Gender Identification and Implications for Disability Evaluation (2024)

Chapter: 8 Chronic Respiratory Disorders

8

Chronic Respiratory Disorders

Chronic respiratory diseases affect the airways and other structures of the lungs. While there are many chronic respiratory diseases, this chapter reviews only those that appear in the disability criteria established by the Social Security Administration (SSA) under 3.00 Respiratory Disorders—Adult and 103.00 Respiratory Disorders—Childhood. SSA further specified that this committee examine only those respiratory disorders that use sex-specific diagnostic criteria. Under SSA’s disability criteria, there are two primary pulmonary function tests that, under current medical guidelines, use sex-specific diagnostic criteria: (1) spirometry and (2) diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Box 8-1 outlines the SSA disability Listings examined in this chapter, all of which contain spirometry and/or DLCO test measurements in disability criteria.

While asthma is a major focus of this chapter, it should be noted that the childhood Listing for asthma is absent from Box 8-1 and from this committee’s charge. As explained in the notes to Box 8-1, SSA’s childhood Listings include asthma as a category (under 103.03). However, to meet criteria for having a disability due to asthma under 103.03, a child applicant is required to demonstrate asthma exacerbations or complications that require hospitalization, but not to provide the results of any pulmonary function test (such as spirometry or DLCO).1 For this reason,

___________________

1 Under 103.03, SSA criteria state that child applicants must show asthma with “exacerbations or complications requiring three hospitalizations within a 12-month period and at least 30 days apart (the 12-month period must occur within the period we are considering in connection with your application or continuing disability review). Each hospitalization must last at least 48 hours, including hours in a hospital emergency department immediately before the hospitalization” (SSA, n.d.-b).

BOX 8-1

Disability Listings for Respiratory Disorders with Sex-Specific Diagnostic Criteria

3.00 Respiratory Disorders—Adult:

3.02: Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CFa

3.03: Asthma

3.04: Cystic fibrosis

103.00 Respiratory Disorders—Childhood:

103.02: Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CFb

103.04: Cystic fibrosis

__________________

NOTES: CF = cystic fibrosis.

a The adult Listing “Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF” (3.02) includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (chronic bronchitis and emphysema), pulmonary fibrosis, pneumoconiosis, and bronchiectasis. This category also includes asthma, which covers cases of overlap between asthma and COPD (known as asthma–COPD overlap syndrome or ACOS).

b The childhood Listing “Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF” (103.02), includes COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, and asthma. The childhood Listings also include chronic lung disease of infancy (also known as bronchopulmonary dysplasia) under 103.02, but measurement of this condition does not include spirometry. For this reason, this report does not address this respiratory condition.

SSA did not include this specific Listing within the committee’s statement of task.2

This chapter describes the multiple respiratory disorders listed in Box 8-1, describes available research on the prevalence of these disorders in transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people and people with variations in sex traits (VSTs), and examines whether and how gender-affirming hormone therapy impacts these disorders and overall lung function. This chapter also reviews the current research on pulmonary function tests,

___________________

2 Other respiratory disorders—including chronic pulmonary hypertension (under 3.09), lung transplant (under 3.11 and 103.11), and respiratory failure (under 3.14 and 103.14)—are not included in this committee’s charge as they do not include spirometry or DLCO measurements as part of the evaluation of disability for these conditions. In addition, this chapter does not include a discussion of lung cancer; while the committee acknowledges there are sex differences in the presentation of lung cancer and disparities for the transgender and gender diverse population, SSA’s Listing for lung cancer (13.14) does not include sex- or gender-specific criteria and, therefore, this condition was not included within the statement of task. SSA childhood Listing 103.06, “Growth failure due to any chronic respiratory disorder,” is within the committee’s purview but included in the discussions of growth failure in Chapter 9.

appropriate evaluation criteria for TGD people or people with VSTs, and what this information means for SSA disability evaluation.

CHRONIC RESPIRATORY DISEASE: PREVALENCE AMONG TRANSGENDER AND GENDER DIVERSE PEOPLE AND PEOPLE WITH VARIATIONS IN SEX TRAITS

Respiratory diseases are common. An estimated 7.7 percent of American adults and children (24.96 million) have asthma (National Center for Environmental Health, 2023), and an estimated 6.5 percent of American adults (14.2 million) have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Liu et al., 2023). While other respiratory diseases are less common, the substantial symptoms experienced by people who have these conditions can cause significant impairment and disability. Some data suggest that TGD people may experience a greater burden of respiratory disease relative to the general population, but respiratory disease is not well researched in TGD people, and few studies have examined these conditions among people with VSTs.

This section reviews the prevalence of asthma, COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, pneumoconiosis, bronchiectasis, and cystic fibrosis and, where possible, describes the known research on these conditions in TGD people and people with VSTs.

Asthma (Adult Listing 3.03)

Asthma is the most common chronic respiratory disease, affecting an estimated 262 million people worldwide (Global Asthma Network, 2022), including approximately 4.7 million children and 20.3 million adults in the United States (National Center for Environmental Health, 2023). Asthma attacks cause inflamed and narrowed airways, making it more difficult for air to flow out of the lungs during exhalation.

Asthma affects people of all ages and often starts during childhood. Of importance to this study, there are well-established sex differences in the prevalence of asthma throughout the lifespan: before adolescence, the prevalence of asthma is higher in populations assigned male sex at birth, but this trend is reversed after adolescence. In addition, after puberty, asthma severity worsens in people who go through typical female puberty compared with those who go through typical male puberty. According to asthma surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2023a), males younger than 18 are more likely than their female counterparts to have asthma, asthma-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations, and mortality due to asthma. After puberty, CDC data show a sex shift in asthma prevalence, whereby asthma becomes

more common among females compared with males, asthma severity (characterized by the rate of hospitalization and emergency department visits) becomes greater for female patients, and asthma-related mortality is higher in females (CDC, 2023a; National Center for Environmental Health, 2023). Gender differences in asthma incidence, prevalence, and severity, along with the postpuberty gender switch in asthma prevalence and severity, have been reported worldwide and indicate the importance of puberty for lung development and function (Almqvist et al., 2008; de Marco et al., 2000; Fu et al., 2014; Schatz and Camargo, 2003; Siroux et al., 2004; Yung et al., 2018; Zein and Erzurum, 2015).

Asthma in Transgender and Gender Diverse Populations

A few studies have attempted to estimate asthma in TGD populations. Using data from the U.S. Transgender Population Health Survey fielded from 2016 to 2018, researchers at the Williams Institute estimate that 208,500 transgender adults in the United States have asthma (Herman and O’Neill, 2020). Overall, research finds that transgender status is associated with a significantly greater risk of lifetime asthma. A 2018 cross-sectional study with a large clinical data set assessed the prevalence of lifetime asthma among transgender people, finding that asthma prevalence was high for transgender men (odds ratio [OR] 2.62; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.40–2.85, p < .001 and highest among transgender women (OR 3.49; 95%CI 3.18–3.84, p < .001) compared with cisgender individuals of the same birth sex (Morales-Estrella et al., 2018).

Other studies have yielded similar results. A 2023 analysis of 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey data showed significantly higher odds of lifetime asthma among transgender men compared with cisgender individuals (Job et al., 2023), and a 2017 study of chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries observed higher percentages of asthma among transgender beneficiaries compared with cisgender beneficiaries (29.6 vs. 13.6 percent) (Dragon et al., 2017). Finally, the Minnesota Student Survey, an anonymous statewide school-based survey on the health and well-being of student populations in Minnesota, found that transgender students reported the highest prevalence of asthma across all grades (Minnesota Department of Health, 2019).

Finding accurate data on asthma prevalence is a challenge, as CDC’s most recent data on asthma prevalence are based on the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which did not ask survey respondents about their gender identity or sex recorded at birth. However, the 2023 NHIS includes questions about gender identity or sex recorded at birth (CDC, 2023b), so future data may provide better estimates of asthma prevalence and severity among TGD populations in the United States.

Asthma in Populations with Variations in Sex Traits

A few studies have examined asthma risk among populations with VSTs. A 2021 study found that androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) is strongly associated with increased asthma risk (18.4 vs. 6.8 percent; p <. 001) (Gaston et al., 2021). The study found that the risk of asthma is higher in individuals with complete AIS than in those with partial AIS, and that both pediatric and adult populations with loss of androgen receptor function are at comparable asthma risk. Men with Klinefelter syndrome (characterized by lower concentration of testosterone) are more likely to be diagnosed with pulmonary diseases compared with men without Klinefelter syndrome (Bojesen et al., 2006), and asthma is also reported in this population (Ladias and Katsenos, 2018; Nan et al., 2013). It is unclear whether the 2023 NHIS will provide any data on asthma and populations with VSTs, as the 2023 questionnaire does not ask about VSTs, and while it asks about sex recorded at birth and gender identity, it does not allow for any free-text responses to these questions where a person might disclose or explain a variation in sex trait (CDC, 2023b).

Chronic Respiratory Disorders Due to Any Cause Except CF (SSA Adult Listing 3.02 and Childhood Listing 103.02)

The SSA Listing “Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF” [cystic fibrosis] is a category of respiratory disorders that includes COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, pneumoconiosis, asthma,3 and bronchiectasis.4,5

___________________

3 Asthma also has its own adult Listing, 3.03, and its own childhood Listing, 103.03. Asthma is also included under the Listing “Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF” (3.02 and 103.02) in recognition of the overlap between asthma and COPD. Asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) is diagnosed for people who have symptoms of both asthma and COPD. It may be difficult for clinicians to distinguish between the two conditions, as asthma and COPD have overlapping symptoms and features. Therefore, for the purposes of disability evaluation, listing criteria under the broader category of 3.02 or 103.02 may be appropriate (ALA, 2023c; de Marco et al., 2013).

4 Bronchiectasis has its own adult Listing, 3.07, but it is also included under “Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF” (3.02) in recognition of the fact that while some people experience bronchiectasis on its own, many will have a dual diagnosis of COPD and bronchiectasis. For disability applicants with both COPD and bronchiectasis, listing criteria under the broader category of 3.02 may be appropriate (Martinez-Garcia and Miravitlles, 2017).

5 The adult Listing “Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF” (3.02) includes COPD (chronic bronchitis and emphysema), pulmonary fibrosis, pneumoconiosis, asthma, and bronchiectasis. The childhood Listing “Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF” (103.02) includes COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, and asthma. The childhood Listing “Chronic lung disease of infancy” (also known as bronchopulmonary dysplasia) is also included, but measurement of this condition does not include spirometry. For this reason, this report does not address this respiratory condition (SSA, n.d.-a,b).

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Of the diseases within this disability Listing, COPD is by far the most common. COPD refers to a group of diseases—including emphysema and chronic bronchitis—that cause airflow blockage and persistent breathing-related problems. In 2021, an estimated 6.5 percent of adults in the United States (14.2 million) had COPD (Liu et al., 2023). Chronic lower respiratory diseases (of which COPD is the main component) were the sixth leading cause of death in the United States in 2021 (Liu et al., 2023).

Sex-specific differences have been reported for COPD. Historically, COPD was considered a disease that impacted mainly elderly men, but in many developed countries, it is now more prevalent among women (Boers at al., 2023; Mannino and Buist, 2007). While increases in rates of smoking among females have contributed to increases in COPD among women, research shows that females compared with males may be more susceptible to developing COPD, may have more severe disease, and may experience a more rapid decline in lung function (Barnes, 2016; Rea et al., 2024; Tam et al., 2011). Given these sex differences, COPD may impact TGD people or people with VSTs differently, but there is very limited research on COPD in these populations:

- COPD and TGD Populations. One study of chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries observed higher percentages of COPD among TGD compared with cisgender beneficiaries (27.3 vs. 20.8 percent) (Dragon et al., 2017). In an analysis of electronic health record data from the Veterans Health Administration, researchers found that, among known TGD veterans who had died between October 1999 and December 2019 (N = 1,415), 15.1 percent had died of COPD, and COPD was the third leading cause of death overall (Henderson et al., 2023). As with asthma, future data may provide better estimates of COPD prevalence among TGD people since the 2023 version of the NHIS, has, for the first time, included questions about sex recorded at birth and gender identity (CDC, 2023b), which could be used to track COPD in these populations.

- COPD and Populations with VSTs. The committee found only one study that examined COPD among populations with VSTs. Bojesen and colleagues (2006) found that men with Klinefelter syndrome are more likely than men without Klinefelter syndrome to be diagnosed with pulmonary diseases, such as COPD. Again as with asthma, despite including questions on sex recorded at birth and gender identity, the 2023 NHIS may not shed light on COPD prevalence among populations with VSTs because the questionnaire does not ask about VSTs or allow for free-text responses, which may prevent people with VSTs from reporting about COPD.

Pulmonary Fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) is a rare disease that causes scarring (fibrosis) of the lungs, which can make it difficult to breathe (ALA, 2023a). Some cases of PF can be caused by other diseases, medication, and/or genetics, or by inhalation of hazardous chemicals. Most often, however, the cause of PF is unknown, and the condition can be referred to as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Although IPF is the most common type of PF, IPF is considered a rare disease, with prevalence rates in North America of 2.40 to 2.98 per 10,000 persons (Maher et al., 2021). However, IPF prevalence has been increasing in recent years, possibly occurring secondary to COVID-19 (Pergolizzi et al., 2023).

IPF is found predominantly in males: in international cohorts, males had a higher prevalence, with 67.7 percent found among males in an Australian registry and 78 percent of males in a study of low-income adults in France (Jo et al., 2017; Sesé et al., 2021). Males also have higher IPF-related mortality (Sauleda et al., 2018). Given its rarity in the population overall, PF has not been studied for TGD populations or populations with VSTs.

Pneumoconiosis

Pneumoconiosis comprises a spectrum of respiratory diseases caused by the inhalation of mineral dust in the lungs, usually as the result of certain occupations. For example, coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, also known as “black lung disease,” occurs when exposure to airborne coal and silica dust causes lung scarring (fibrosis), impairing the ability to breathe. While coal worker’s pneumoconiosis declined over time in the United States with increased workplace safety procedures for coal miners, the disease has been on the rise since 2000, an increase that may be linked to changes in coal mining technology that appear to impact lung health negatively (Shriver and Bodenhamer, 2018). Researchers estimate the prevalence of coal worker’s pneumoconiosis to be more than 10 percent among miners who have worked for 25 years or more (Potera, 2019). Men have higher occupational exposures associated with the development of pneumoconiosis (Shi et al., 2020), and therefore, the condition is found predominantly in men. Pneumoconiosis has not been studied for TGD populations or populations with VSTs.

Bronchiectasis

In this chronic lung condition, the walls of the bronchi or airways become irreversibly thickened and damaged, a phenomenon associated with persistent airway inflammation, chronic cough mucus buildup, and risk of infection (Chalmers et al., 2018). While it is often linked to CF,

bronchiectasis can result from other conditions, including COPD and asthma, and it can also be caused by infections such as pneumonia, pertussis (whooping cough), and tuberculosis (ALA, 2024). Non-CF bronchiectasis was once considered an orphan disease, but its prevalence is increasing worldwide as a result of improved and increased use of imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) scans (Imam and Duarte, 2020). In one study of data from Medicare prescription drug plans, the average annual prevalence of bronchiectasis from 2012 to 2014 was 701 per 100,000 persons (Henkle et al., 2018), and the American Lung Association (2024) estimates that bronchiectasis affects an estimated 350,000 to 500,000 adults in the United States. The risk of developing bronchiectasis increases with age, and the condition is more common in women than in men (Henkle et al., 2018; Seitz et al., 2012). However, no studies have been published on the prevalence of bronchiectasis among TGD populations and populations with VSTs.

Cystic Fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive inherited life-limiting disease that affects more than 40,000 adults and children in the United States, according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) Patient Registry (CFF, n.d.-a.), and upward of 160,000 people worldwide (Guo et al., 2022). CF is a multisystem disorder, but people with CF most commonly die of complications of progressive respiratory failure (Mall and Elborn, 2014).

Multiple epidemiologic studies show that CF is a disease of equal incidence in females and males (given its autosomal recessive nature), but that females exhibit a decreased life expectancy, largely because of more severe lung disease (Harness-Brumley et al., 2014; Rosenfeld et al., 1997). Reports using the U.S. CFF Patient Registry show worse outcomes in females relative to males, even after adjusting for confounding morphometric, nutritional, and comorbid factors. In addition, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, one of the most common and pathogenic bacteria in CF, is acquired earlier and associated with a more rapid decline in lung function and higher mortality in females versus males with CF (Harness-Brumley et al., 2014; Rosenfeld et al., 1997). Etiologies for this differential are likely multifactorial, but sex hormones have been implicated. Several pathophysiology studies suggest that estrogen can convert Pseudomonas aeruginosa to a more pathogenic mucoid form, increases mucus synthesis in airway epithelium, is associated with more pulmonary inflammation, and inhibits calcium-mediated chloride channels on the airway epithelial cell surface—all of these factors may contribute to the sex disparity in CF (Abid et al., 2017; Chotirmall et al., 2012; Coakley et al., 2008; Demko et al., 1995; Holtrop et al., 2021; Tam et al., 2014).

Cystic Fibrosis and TGD Populations

No published data exist on the prevalence of CF among TGD populations (Shaffer et al., 2021). However, researchers have estimated that 200–300 people with CF may identify as TGD (Shaffer et al., 2022).

Cystic Fibrosis and Populations with VSTs

CF is known to have a major impact on male reproductive health, and has been linked with male hypogonadism, a condition whereby the body does not produce enough testosterone during puberty (Khan et al., 2022; Yoon et al., 2019). CF is also genetically linked to congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens, a rare obstructive anomaly that contributes to male factor infertility; nearly 95 percent of men with CF have this condition (de Souza et al., 2018; Hannema and Hughes, 2007). Cases of people with Turner syndrome and CF have been reported, but CF has not been studied in this population (Wu et al., 2022).

IMPACT OF GENDER-AFFIRMING HORMONE THERAPIES ON LUNG FUNCTION

The pathophysiology of respiratory diseases is complex, and many factors may contribute to sex differences in chronic respiratory disorders. These include the influence of sex differences on environmental factors, such as differing immune responses to viral infection (Malinczak et al., 2019), rhinitis prevalence (Pinart et al., 2017), and different exposures to asthma-causing triggers, as well as the contribution of specific genetic risk factors, which differs between males and females (Hunninghake et al., 2010; Ranjbar et al., 2020). However, since females experience greater prevalence, morbidity, and mortality for many respiratory diseases, some research has examined the role of circulating female hormones (estradiol and progesterone) and male hormones (androgen or testosterone) in these conditions. This section examines sex hormones, their impact on respiratory disease, and the potential impact of gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) on lung function.

Asthma

Circulating sex hormones from endogenous and exogenous sources may influence sex differences in asthma-related outcomes in adults (McCleary et al., 2018; Zein et al., 2021). The trends observed in asthma prevalence and severity suggest that hormonal changes occurring during puberty may contribute to the increased incidence of asthma in adult females (McCleary et al.,

2018; Naeem and Silveyra, 2019; Sathish et al., 2015). In general, research shows that estrogen and progesterone aggravate asthma and other allergic diseases, whereas androgen and testosterone suppress such diseases. Studies show that androgens may have a beneficial effect on lung function and may protect against asthma in adults through systemic and airway-specific anti-inflammatory effects (Becerra-Diaz et al., 2020; Han et al., 2020; McManus et al., 2022; Mohan et al., 2015), while estrogen and progesterone may have a detrimental effect on adult lung function, increasing allergic airway inflammation (DeBoer et al., 2018; Fuseini and Newcomb, 2017; Han et al., 2020; McCleary et al., 2018).

It is important to take into account the impact of hormones on the lungs when considering lung function for TGD people who have asthma and who may have accessed GAHT in puberty or adulthood. As described in detail in Chapter 5, some TGD adolescents may elect to delay puberty (using puberty blockers) and later access GAHT to go through the puberty of their affirmed gender. Other TGD people may complete the puberty of their birth sex and later access GAHT in adulthood. These treatment decisions impact what hormones were present during puberty, which in turn may impact the eventual size and function of the lungs, along with risks for asthma or other lung conditions (Fechter-Legget, 2023).

Researchers hypothesize that because of the important role of hormones in lung development during puberty, populations who access GAHT prior to or during puberty could be expected to have lung size more aligned with their affirmed gender rather than with their sex recorded at birth (Turner et al., 2021). However, more research is needed to understand fully whether and how GAHT during puberty affects lung function and, consequently, acute and/or long-term asthma risk.

For TGD populations that access GAHT in adulthood (after first going through natal puberty), the impact of these exogenous hormones on asthma prevalence and severity is inconclusive and has not been well studied. One cross-sectional study with a large clinical data set assessed the prevalence of lifetime asthma among TGD individuals. The researchers hypothesized that transgender women (who take exogenous feminizing hormone therapy) would have a higher risk of asthma compared with transgender men (who take exogenous masculinizing hormone therapy); however, the study did not show a causative effect of gender-affirming masculinizing or feminizing hormone therapy (Morales-Estrella et al., 2018).

Studies of cisgender populations have found similar conflicting and unclear results when examining the impact of exogenous hormone therapy on asthma incidence and severity. Several studies of pre- and postmenopausal women using hormone replacement therapy show increased risk of asthma onset (Bønnelykke et al., 2015; Gómez Real et al., 2006; Shah and Newcomb, 2018; Troisi et al., 1995; Zemp et al., 2012). However, the

findings of studies on this topic are inconsistent, and evidence on the role of exogenous female hormones in asthma severity in women is conflicting (Carlson et al., 2001; Naeem and Silveyra, 2019; Shah et al., 2021), with some studies showing that the use of these hormones may in fact decrease asthma risk in women (Zhang et al., 2023).

Chronic Respiratory Disorders Due to Any Cause Except CF

Studies have examined the factors that may contribute to COPD among females. As smoking and exposure to cigarette smoke are major contributors to COPD risk, studies have examined the role of sex hormones in metabolism of cigarette smoke. In studies using mice models, airways of female mice demonstrated greater injury when exposed to cigarette smoke than airways of male mice (Chichester et al., 1994; Van Winkle et al., 2002). Testosterone, on the other hand, may be protective. In a 2023 study of two separate large COPD cohorts (with baseline measurement of testosterone and longitudinal data pertaining to health outcomes in both men and women), researchers demonstrated that circulating testosterone levels are not associated with COPD exacerbations or all-cause mortality (Pavey et al., 2023).

Compared with research on asthma, research on COPD and GAHT is much more limited, with only one published case report examining COPD for a transgender female (Cortes-Puentes et al., 2023). In a 2023 scoping review of existing research on health inequities surrounding the treatment and prevention of COPD, the authors uncovered only one study examining LGBTQ+ populations with COPD and no studies researching GAHT’s impact on lung function in TGD patients with COPD (Rea et al., 2024).

The impact of endogenous hormones or GAHT on pulmonary fibrosis, pneumoconiosis, and bronchiectasis has not been examined in detail.

Cystic Fibrosis

Little is known about the effect of GAHT on a person with CF. Two case reports of transgender women with CF who were treated with estrogen gender-affirming therapy show a potential decline in health. One case showed a decline in lung function as estrogen levels rose, and the other showed acquisition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for the first time after initiation of the hormone therapy (Lam et al., 2020; Shaffer et al., 2021). Whether either of these findings is directly related to the hormone treatment is unknown.

Importantly, people with CF have higher rates of anxiety and depression relative to the general population, as do individuals who identify as LQBTQ+ (Guta et al., 2021; Latchford and Duff, 2013; Riekert et al., 2007). Given the impacts of mental health on health outcomes in CF, it is critical to factor in mental health when making decisions about GAHT for people with CF.

IMPACT OF CHEST BINDING ON LUNG FUNCTION

“Chest binding” is any activity that involves compressing breast tissue to create a flatter chest appearance.6 Some TGD people assigned female sex at birth may use chest binding to reduce the appearance of their breasts as a way of achieving a more masculine gender expression (Dutton et al., 2008; Maycock and Kennedy, 2014). Some people with VSTs may also use chest binders (Jarrett et al., 2018). Chest binding is a common practice, used by 87 percent of TGD respondents in one study (Jones et al., 2015). For transgender men, chest binding is not merely an elective activity to enhance appearance, but is an essential daily practice for reducing chest dysphoria (discomfort and distress from unwanted breast development), improving mental health outcomes, and increasing the sense of safety in public (Julian et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2019; Peitzmeier et al., 2022). Chapter 5 describes chest binding in further detail.

Minimal research exists on the use of chest binders, but some studies indicate their impact on pulmonary function. One study of transgender men who had either current or previous experience with chest binding (N = 1,273, all of whom had been assigned female sex at birth or had VSTs), found that more than half (51.7 percent) had a respiratory complaint (Jarrett et al., 2018). Another study found that transgender men who wore chest binders experienced several negative physical effects that implicate lung health, such as shortness of breath (46.6 percent of survey respondents), chest pain (48.8 percent), scarring (7.7 percent), or rib fractures (2.8 percent) (Peitzmeier et al., 2017). The authors of this study caution that their chest binding survey did not measure the severity of symptoms among respondents, did not assess whether these symptoms were transient or persistent, and may not be representative of all people who bind (Peitzmeier et al., 2022). There are no published data on the impact of chest binders on specific respiratory diseases such as asthma, COPD, or CF.

RESPIRATORY DISEASE AND SSA DISABILITY DETERMINATION

In addition to being common, respiratory conditions can lead to significant impairment and disability. Many people with respiratory diseases live active lives, but some experience severe symptoms and complications that may impact their ability to work or complete certain daily activities.

Severe Asthma

The symptoms of an asthma attack—shortness of breath, chest tightness, wheezing, or coughing—can often be managed by medication and by

___________________

6 Examples of chest binding include wearing one or multiple sports bras, wrapping the chest with elastic bandages, and wearing specially designed commercial binders.

avoiding the triggers that can cause an attack. When asthma is not well controlled, however, some people may require more intensive or prolonged treatment, with frequent emergency room visits or hospitalizations. Asthma accounted for 94,560 discharges from hospital inpatient care and nearly 1 million emergency department visits in 2020, and for 6.5 percent of all physician office visits in 2019 (Santo and Kang, 2023). People with severe asthma may have to limit activity because of the frequency and severity of asthma attacks.

Advanced COPD

Common COPD symptoms are shortness of breath, coughing, and difficulty breathing deeply; with advanced COPD, these symptoms can progress to the point where an individual is too breathless to leave the home (Miravitlles and Ribera, 2017). People with advanced COPD may require frequent emergency care and hospitalization: COPD accounted for 791,000 emergency department visits in 2020, and research indicates that up to 19 percent of people with COPD who experience an exacerbation will require hospital admission (Cairns and Kang, 2021), and up to 24 percent will be readmitted within 30 days of discharge (Miravitlles et al., 2023). People with COPD can have additional extrapulmonary symptoms, including muscle wasting, cardiovascular disease, depression, osteopenia, and chronic infections (Barnes, 2010). When COPD is severe, symptoms of the condition can affect a person’s ability to complete certain daily activities, such as walking or performing manual tasks.

Advanced CF

The severity of CF symptoms can vary widely from person to person. Symptoms can be managed through airway clearance, inhaled medications, and regular physical activity (CFF, n.d.-a.). Those with advanced CF may have significant difficulty breathing, leading to severe discomfort and the need for daily oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, and symptom and pain management from palliative care specialists (CFF, n.d.-b.). In addition, CF may cause recurrent infections of the lungs and sinuses and impact other organs and systems, causing pancreatic insufficiency, gastrointestinal dysmotility, CF-related diabetes, arthropathy, and bone disease (Basile et al., 2023). These symptoms and complications may cause lengthy hospitalizations: studies from the United States and United Kingdom have found that CF patients have mean lengths of hospital stays of 9 days (Bradley et al., 2013; Vadagam and Kamal, 1995). For patients at this stage of disease, it may be difficult to continue working because of time-consuming treatments and the inability to engage in physical activity because of breathing difficulties.

The significant symptoms that occur with advanced respiratory disease can cause severe impairment and disability. These factors lead people with asthma, COPD, CF, and other respiratory diseases to seek disability benefits from SSA. As a whole, respiratory diseases accounted for 2.4 percent of all Social Security Disability Income (SSDI) recipients (217,378 people) and 1.75 percent of Supplemental Security Income recipients (91,328 people) according to 2022 data published by SSA (2022, 2023).

Pulmonary Function Tests and SSA Disability Criteria

A person (child or adult) with respiratory disease must show medical evidence to SSA documenting the severity of their condition. While medical evidence may include many things (e.g., a description of a patient’s reaction to prescribed treatment or evidence of recurrent hospitalizations), a primary piece of medical evidence to support a respiratory disability application is the result of one or more pulmonary function tests (PFTs). Monitoring pulmonary function is central to discussions about respiratory health for people with asthma, COPD, CF, and other respiratory diseases, and most people with respiratory concerns will have medical records that contain documentation of a PFT.

Table 8-1 outlines the various PFTs accepted under SSA disability criteria for Listings 3.02, 3.03, 3.04, 103.02, and 103.04, along with sex-specific criteria used for disability evaluation.

Questions around sex and gender identity become important for certain PFTs, given that SSA’s respiratory disease Listings follow current medical guidelines by including sex-specific diagnostic criteria, as outlined in Table 8-1. This section examines spirometry and DLCO tests, sex-specific components of these tests, and whether modified or alternative approaches to spirometry and DLCO are appropriate for TGD people and people with VSTs.

Spirometry

Spirometry, the most common PFT, plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of chronic lung conditions (Graham et al., 2019). Spirometry tests assess how well a patient’s lungs work by measuring how much air they can breathe in and out of their lungs and how efficiently they can exhale air from their lungs (ALA, 2023b). These results may be used to monitor the progression of lung disease and response to therapy.

Key spirometry measurements include the following:

- Forced expiratory volume (FEV1). The volume of air a person exhales in the first second of the spirometry test. Lower FEV1

| Listing | Pulmonary Function Test Included in Criteria | Sex-Specific Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 3.00 Respiratory Disorders—Adult | ||

| 3.02 Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF |

Spirometry

|

An adult claimant’s FEV1 or FVC value must be less than or equal to the value in the table for the claimant to meet disability criteria.

|

| Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (3.02C1) |

Average of two unadjusted, single-breath DLCO measurements less than or equal to the table value.

|

|

| Arterial blood gas (ABG) test (3.02C2)a | None | |

| Pulse oximetry (3.02C3)b | None | |

| 3.03 Asthma |

Spirometry

|

An adult claimant’s FEV1 value must be less than or equal to the value in the table for the claimant to meet disability criteria.

|

| 3.04 Cystic fibrosis |

Spirometry

|

An adult claimant’s FEV1 value must be less than or equal to the value in the table for the claimant to meet disability criteria.

|

| Pulse oximetry (3.04F)b | None | |

| Listing | Pulmonary Function Test Included in Criteria | Sex-Specific Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 103.00 Respiratory Disorders—Childhood | ||

| 103.02 Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF |

Spirometry

|

A child claimant’s FEV1 or FVC value must be less than or equal to the value in the table for the claimant to meet disability criteria.

|

| 103.04 Cystic fibrosis |

Spirometry

|

|

a An ABG test—which measures the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the blood, as well as the blood’s acidity (pH)—is one of the tests used for COPD diagnosis. It does not have sex-specific criteria, meaning a provider does not interpret readings differently for male and female patients.

b Pulse oximetry measures arterial oxygen saturation levels (how much oxygen the hemoglobin in the blood is carrying) and is commonly used in the management of COPD, CF, and other lung conditions to check pulmonary function. A pulse oximetry reading can help a provider determine whether a patient requires supplemental oxygen or whether hospitalization may be appropriate. Pulse oximetry measurements do not have sex-specific criteria, meaning a provider does not interpret readings differently for male and female patients.

NOTE: CF = cystic fibrosis; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SSA = Social Security Administration.

SOURCES: SSA, n.d.-a., n.d.-b.

- readings indicate greater severity of breathing problems and more significant obstruction. SSA uses an applicant’s highest FEV1 value to evaluate respiratory function under 3.02A/103.02A (“Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF”), 3.03A (“Asthma”),7 and 3.04A/103.04A (“Cystic fibrosis”).

- Forced vital capacity (FVC). The maximum amount of air a person can forcefully exhale after breathing as deeply as possible. An FVC reading lower than normal indicates restricted breathing. Under 3.02B/103.02B (“Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF”), SSA uses an applicant’s highest FVC value to evaluate respiratory function.

Questions around sex and gender identity become important in spirometry testing because spirometry values are calculated based on age, height, and sex (Stanojevic et al., 2022).

Current recommendations from the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society (ERS/ATS) advise clinicians that “biological sex” is the appropriate reference sex for calculating percent predicted values and interpreting spirometry results (Graham et al., 2019; Stanojevic et al., 2022). While the guidelines acknowledge the importance of gender identity, they make clear that sex recorded at birth is the more accurate predictor of lung size. The 2022 ERS/ATS Technical Standard on Interpretive Strategies for Routine Lung Function Tests (ERS/ATS Technical Standard) states (Stanojevic et al., 2022):

Sex is an important predictor of lung size, even after accounting for differences in height. Thus, while gender identity should be respected, use of biological sex will yield a more accurate prediction of lung function. (p. 6)

These guidelines echo the ERS/ATS Standardization of Spirometry, 2019 Update, which states (Graham et al., 2019):

When requesting birth sex data, patients should be given the opportunity to provide their gender identity as well and should be informed that although their gender identity is respected, it is birth sex and not gender that is the determinant of predicted lung size. Inaccurate entry of birth sex may lead to incorrect diagnosis and treatment. (p. e75)

___________________

7 SSA criteria do not ask for a spirometry test under the childhood Listing for asthma (103.03). A child applicant will meet criteria for disability due to asthma with evidence of exacerbations or complications requiring three hospitalizations (of at least 48 hours) within a 12-month period and at least 30 days apart (SSA, n.d-b).

Diffusing Capacity of the Lungs for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO)

DLCO is a measure used to assess the lungs’ ability to transfer oxygen to the bloodstream upon inhalation (Modi and Cascella, 2024). SSA includes DLCO under disability evaluation criteria for Listing 3.02, “Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF.”

The results of a DLCO test are given as a percentage of what a given patient’s expected DLCO (predicted value) would be based on age, height, and sex. A low DLCO value means the lungs are not working efficiently to move oxygen from the air to the bloodstream. Table 8-2 shows the classification of DLCO, which is used to indicate the severity of respiratory disease.

The most recent ERS/ATS guidelines for DLCO, from 2017, call for the value of DLCO to vary with age, height, and sex (Graham et al., 2017). In contrast with spirometry, the DLCO guidelines do not mention whether and how gender identity should be assessed when interpreting DLCO tests.

PFT Interpretation for TGD People and People with VSTs

Given unclear evidence about how puberty-delaying medications and GAHT impact measurements of lung function, current spirometry guidelines do not call for modified spirometry measurements for TGD populations. However, the ERS/ATS Technical Standard recognizes that the impact of GAHT on lung function is not well understood and could be important for spirometry interpretation (Stanojevic et al., 2022):

The effect of gender-affirming hormonal therapy on lung function is poorly understood, so the appropriate reference equation for transgender individuals is currently not known. Timing of gender reassignment, especially during adolescence, may impact lung growth and development and thus needs to be considered when interpreting results during adulthood. (p. 6)

For health care providers measuring lung function in TGD patients or patients with VSTs, it is not always clear which chart—male or female—is the more appropriate to use, and providers may get it wrong. Interpretation

| Normal DLCO | Lungs functioning at >75% of predicted value, up to 140% |

| Mildly reduced DLCO | 60–75% of the lower limit of normal predicted value |

| Moderately reduced DLCO | 40–60% |

| Severely reduced DLCO | <40% |

SOURCE: Adapted from Modi and Cascella, 2024.

of PFTs using an inappropriate reference sex could lead to errors in either identifying a pulmonary abnormality that does not exist or failing to identify a pulmonary abnormality that does exist.

Part of the challenge in selecting the appropriate reference sex is that medical records may contain incorrect information (e.g., incorrect sex recorded in the patient chart), or providers may not ask questions that would provide a complete picture of patient characteristics (e.g., failing to ask about VSTs or about gender identity as separate from sex recorded at birth). Chapter 3 of this report describes these challenges in greater detail, but they are worth mentioning again here as the realities of medical record data collection can certainly impact interpretation of PFTs for TGD patients and patients with VSTs. Moreover, even when medical records contain a complete and accurate record of gender identity and sex recorded at birth such that providers are aware they are assessing a TGD patient or a patient with a VST, providers may lack familiarity with caring for these patients and may not know how or when TGD or VST lived experience impacts patient care and clinical decision making.

A few studies describe how choice of sex reference impacts PFT interpretation for TGD people. One study examining providers’ reference sex choice for 15 TGD patients found that providers used female and male reference ranges inconsistently for these patients (Foer et al., 2021). Overall, providers predominantly selected a female reference range, independent of gender identity: a female reference was used to interpret PFTs for 60 percent of transgender men, 75 percent of transgender women, and 100 percent of gender nonbinary patients (Foer et al., 2021). The researchers found that use of the other gender reference range affected PFT interpretation, concluding that it may be appropriate to use both binary reference ranges for PFT interpretation to improve shared decision making with TGD patients.

Prior research has also described how reference choice impacts spirometry interpretation in particular, and how PFT interpretations based on the incorrect sex may place patients at risk for misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment (Al-Hadidi and Baldwin, 2017; Haynes and Stumbo, 2018). Inaccurate medical tests, including misinterpretation of spirometry, can be especially harmful to TGD populations, as they already face stigma; discrimination; and systematic barriers, both institutional and structural.

Chest Binders and Pulmonary Function Tests

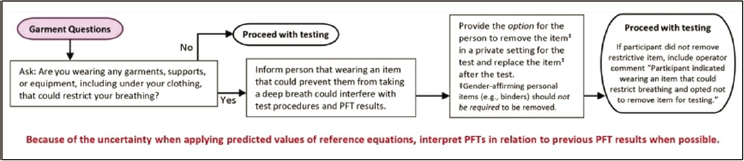

To obtain an estimate of lung function without restrictions in place, clinicians may ask patients to remove their chest binder or other restrictive clothing. As described above, however, for some TGD people, chest binders

are worn daily and for extended periods of time as a critical component of gender-affirming care. Where a patient has removed their chest binder for the purposes of undergoing a PFT, that measurement of lung function may not take into account their daily lived experience. For this reason, it may be appropriate for some patients to continue wearing their binder during a PFT, and clinicians who are attuned to the needs of their TGD patients or patients with VSTs may engage them in decision making about the best approach to PFT measurement. However, medical records may not indicate whether a chest binder was worn during a PFT.

Alternative Measurements

To eliminate the error in selection of a reference sex for TGD and VST populations, using measures that are independent of sex may be preferable. Pulse oximetry and arterial blood gas tests (described in Table 8-1) are tests accepted by SSA that do not have sex-specific criteria and may be appropriate for measuring lung function in people with certain respiratory conditions, including COPD and CF.

In theory, it might be possible to devise alternative measures of lung function, such as calculating height along with chest circumference to predict the shape and size of a patient’s thoracic cavity. As these kinds of measures are independent of sex or other variables (such as age), they could serve as a more accurate functional measure compared with a PFT (Fechter-Leggett, 2023). However, the currently available prediction equations include sex as a variable. While the ERS/ATS spirometry guidelines state that height may be a reasonable proxy for chest size, the authors state: “Sex is an important predictor of lung size, even after accounting for differences in height” (Stanojevic et al., 2022, p. 6).

Until guidelines shift to a sex-independent reference metric, providers will continue using reference sex in interpreting PFTs.

Dual Calculations

While current guidelines do not call for running PFT results against both reference sex ranges, some practitioners conducting spirometry for TGD patients use dual PFT calculations in practice to improve decision making for their patients (Foer, 2023). Guidelines in other clinical specialties—for example, measurements of bone mineral density (Rosen et al., 2019)—state that providers and patients may consider using both binary reference ranges as an option to improve clinical decision making. The strategy for running interpretations under both sex ranges has also been put forward for assessing body mass index in young TGD people (Kidd et al., 2019).

Terminology in SSA Criteria

As noted, current ERS/ATS recommendations advise that sex recorded at birth is the appropriate sex to use when interpreting spirometry and DLCO test results (Graham et al., 2017, 2019; Stanojevic et al., 2022). However, as displayed in Table 8-1, SSA’s disability criteria use the term “gender” in reference to these measurements of lung function: “values are calculated by gender and height without shoes” [emphasis added]. This language may incorrectly indicate that it is “gender identity” that is determinative when interpreting lung function in Listings related to respiratory disease. The conflation of these terms throughout disability evaluation criteria can lead to confusion for both applicants and adjudicators. SSA might consider updating language under 3.02. 3.03, 3.04, 103.02, and 103.04 to reflect current guidelines. For example, under 3.02 (adult Listing for asthma), SSA criteria state:

“For adults aged 18 and older, FEV1 values are calculated by gender and height without shoes” [emphasis added].

This language would better reflect current guidelines if it read:

“For adults aged 18 and older, FEV1 values are calculated by sex recorded at birth and height without shoes.”

SELECTING APPROPRIATE PULMONARY FUNCTION TEST REFERENCE SEX FOR TRANSGENDER ADULTS: AN INNOVATIVE APPROACH

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) leads research on worker safety and health. As a research agency within CDC, NIOSH does not engage in regulation or enforce workplace safety regulations; these functions are within the purview of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA, 2013) within the Department of Labor. Rather, NIOSH funds and conducts research, makes recommendations, provides technical assistance, and trains occupational safety and health professionals to ensure safe and healthful working conditions for all Americans. NIOSH’s Respiratory Health Division focuses on researching, identifying, evaluating, and preventing work-related respiratory diseases, such as work-related asthma, COPD, and pneumoconiosis (NIOSH, 2018). Through field studies, it evaluates the frequency and severity of respiratory disease within various workplaces—for example, where workers are required to wear a respirator during work or perform jobs that cause exposure to possible lung hazards (e.g., asbestos)—and provides workplaces with appropriate recommendations for respiratory disease prevention (NIOSH, 2018).

The Respiratory Health Division uses spirometry testing as a primary means of surveilling respiratory health across the workforce. In 2019, NIOSH set out to develop better spirometry testing procedures and protocols for TGD workers (Fechter-Leggett et al., 2022). NIOSH’s concern is that common PFT protocols—which state that to predict lung function, PFTs should be compared against a reference range corresponding to a person’s sex recorded at birth—may not be appropriate for TGD workers, particularly those who were treated with puberty-delaying medications and began GAHT during puberty. These concerns are echoed by the ERS/ATS standards, which state: “Timing of gender reassignment, especially during adolescence, may impact lung growth and development and thus needs to be considered when interpreting results during adulthood” (Stanojevic et al., 2022, p. 6).

NIOSH Algorithm for Selection of Reference Sex

As noted above, if PFTs are interpreted with an inappropriate reference sex, the result could be either identifying a pulmonary abnormality that does not exist or failing to identify a pulmonary abnormality that does. To correct for these potential errors, NIOSH consulted with national experts in designing questions and an algorithm to inform the selection of a PFT reference sex for all adults, including TGD adults (Fechter-Leggett et al., 2022). The algorithm acknowledges that use of puberty-delaying medications (using the terminology “hormone blocking medications”) and GAHT during puberty could impact PFT results. Therefore, instead of using “sex recorded at birth” as the metric for choosing the PFT reference sex, the algorithm uses “hormonal sex at puberty,” or the hormone that was predominant during puberty (estrogen or testosterone) that influenced the shape and size of the thoracic cavity.

NIOSH’s panel of experts reasoned that when people wait until adulthood to begin GAHT, their body completes the puberty of their sex recorded at birth. For these individuals, their body size and habitus, along with their thoracic cavity, can reasonably be expected to follow a pattern similar to that of peers of their same sex recorded at birth (Fechter-Leggett, 2023). For these individuals, the appropriate PFT reference sex may be their sex recorded at birth. However, the use of puberty-delaying medications and initiation of GAHT during puberty could promote the development of a body habitus similar to that of a person’s affirmed gender. For this portion of the transgender population, affirmed gender—not sex recorded at birth—may be the more appropriate PFT reference sex.

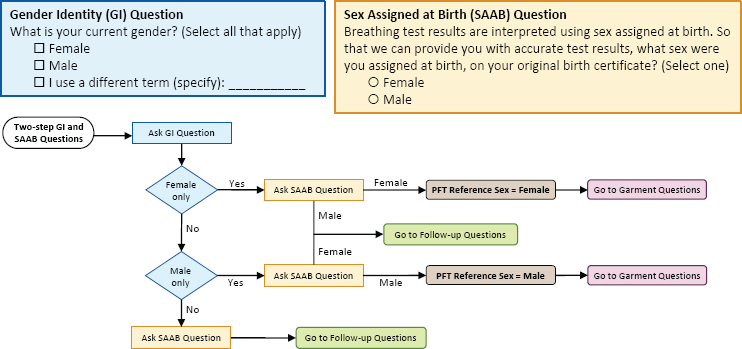

NIOSH’s algorithm starts with asking gender identity and sex recorded at birth (referred to as “sex assigned at birth” or “SAAB”) in two separate questions, as shown in Figure 8-1. For most workers being tested for pulmonary function, their gender identity and sex recorded at birth will be

SOURCE: Presented by Fechter-Leggett on September 14, 2023.

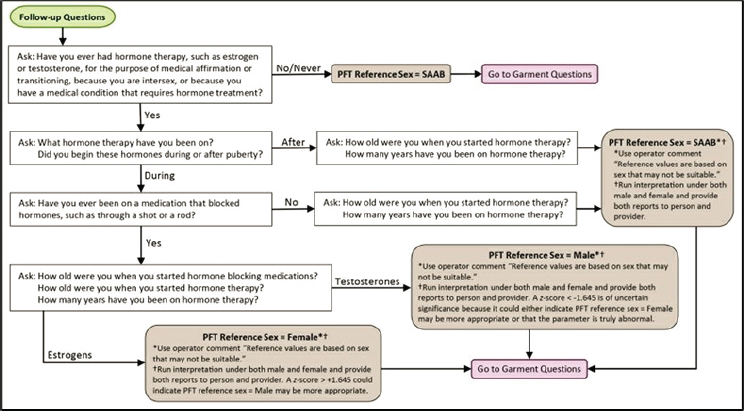

the same and determining the appropriate PFT reference sex requires only those two demographic questions. For people who have a different gender identity from their sex recorded at birth, the algorithm proceeds to a series of additional questions related to the use and timing of hormone therapy to determine the appropriate PFT reference sex (see Figure 8-2). Within these

SOURCE: Presented by Fechter-Leggett on September 14, 2023.

follow-up questions, the algorithm recognizes that not all individuals access hormone therapy for the purposes of gender affirmation. The first follow-up question encompasses persons with VSTs (using the terminology “intersex”) and other populations that have a medical condition that requires hormone treatment. For all patients, there is a garment question to determine whether any garments are being worn that could interfere with PFT results, such as chest binders (Figure 8-3).

The algorithm guides providers in selecting the PFT reference sex most appropriate to the individual worker’s gender identity and medical history. Ultimately, however, the available PFT reference ranges were constructed for a cisgender population. For individuals who have accessed hormone therapy, the reference values may be unsuitable regardless of which reference range is selected (male or female). For this reason, NIOSH’s algorithm instructs providers to “run interpretation under both male and female and provide both reports to person and provider,” and gives further instructions on interpreting these results (Figure 8-2). There is also a note at the bottom of the algorithm (shown in Figure 8-3) instructing clinicians to compare the current PFT results with those of previously recorded PFTs, where possible.

The algorithm distinguishes between individuals who began hormone therapy “during” and “after” puberty. Additional follow-up questions are included, such as “How old were you when you started hormone blocking medications?,” “How old were you when you started hormone therapy?,” and “How many years have you been on hormone therapy?” At this time, these questions do not impact decision making. For example, if two people began hormone therapy in adulthood, and one has been on hormone therapy for 2 years and the other on the same therapy for 25 years, the algorithm does not distinguish between these individuals. However, if future research determines that length of time on hormone therapy (or, e.g., age at onset of puberty-delaying medication) impacts lung function or severity of respiratory outcomes, then, by collecting these data today, providers can later reinterpret PFT results (Fechter-Leggett, 2023).

SOURCE: Presented by Fechter-Leggett on September 14, 2023.

NIOSH is currently in the process of integrating the algorithm for selection of PFT reference sex into its work. The Respiratory Health Division expects to deploy, test, and evaluate the algorithm and its accompanying questions in field studies (Fechter-Leggett, 2023).

Sex Selection and Impact on Eligibility for SSDI

Dr. Ethan Fechter-Leggett, Research Epidemiologist, Field Studies Branch, NIOSH Respiratory Health Division, presented to the committee preliminary data on estimating the impact of decisions about reference sex on populations applying for SSDI (Fechter-Leggett, 2023). Using data from the 2007–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), Fechter-Leggett’s team analyzed data on all adults over 18 who had acceptable spirometry documented (best-test FEV1 and FVC estimates had quality ratings of A, B, or C as defined by the survey) and did not have missing height measurements (N = 13,589). Using SSA disability criteria under adult Listings 3.02, “Chronic respiratory disorders due to any cause except CF,” and 3.03, “Asthma,” the researchers analyzed how often the individuals included in the data set would meet SSA disability criteria using sex recorded at birth (sex in the NHANES data set is assumed to be sex recorded at birth) versus using the opposite sex. Tables 8-3 and 8-4 show preliminary results of this analysis.

As might be expected, most of the individuals in the data set (98 percent of those under criteria for 3.02 and 91.2 percent of individuals under criteria for 3.03) did not meet SSA disability criteria with either reference sex; for these individuals, changing the PFT reference sex would not ultimately change eligibility for SSDI. A small percentage (1.1 percent of individuals under criteria for 3.02 and 4.4 percent of those under criteria for 3.03)

| Sex Recorded at Birth* | Opposite Sex | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Does not meet 3.02A/B criteria | Meets 3.02A/B criteria | Total | |

| Does not meet 3.02A/B criteria | 13,314 (98%) | 87 (0.6%) | 13,401 |

| Meets 3.02A/B criteria | 41 (0.3%) | 147 (1.1%) | 188 |

| Total | 13,355 | 234 | 13,589 |

* Sex in the data set is assumed to be sex recorded at birth.

SOURCE: Fechter-Leggett, 2023.

TABLE 8-4 Listing 3.03A: FEV1 Criteria for Asthma

| Sex Recorded at Birth* | Opposite Sex | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Does not meet 3.03A criteria | Meets 3.03A criteria | Total | |

| Does not meet 3.03A criteria | 12,399 (91.2%) | 412 (3.0%) | 12,811 |

| Meets 3.03A criteria | 185 (1.4%) | 593 (4.4%) | 778 |

| Total | 12,584 | 1,005 | 13,589 |

* Sex in the data set is assumed to be sex recorded at birth.

SOURCE: Fechter-Leggett, 2023.

met SSA disability criteria under both reference sexes; for these individuals, their lung function was poor enough that they would meet disability criteria under either scenario.

The remaining portion of the data set (0.9 percent of individuals under criteria for 3.02 and 4.4 percent of those under criteria for 3.03) had discordant results. For these individuals, if their spirometry test were interpreted with the opposite reference sex, they had a change in ability to meet SSDI disability criteria. All persons with sex recorded male at birth with discordant results (0.3 percent of those under criteria for 3.02 and 1.4 percent of those under criteria for 3.03) would no longer meet SSA disability criteria if evaluated with the opposite reference sex. All persons with sex recorded female at birth with discordant results (0.6 percent of those under criteria for 3.02 and 3.0 percent of those under criteria for 3.03) would meet disability criteria if evaluated with the opposite reference sex.

Overall, percent discordance differed by sex and was greater among persons with sex recorded female at birth. When breaking the data down by race/ethnicity, researchers found a larger percentage discordant results among non-Hispanic Black persons (both with sex recorded male at birth and sex recorded female at birth). Differences by race/ethnicity and sex highlight potentially disproportionately affected groups if an inappropriate reference sex is used for PFT interpretation.8

___________________

8 The population in the NHANES data set is not the same as the population applying for disability benefits, so percentages of discordant results could be different among SSA disability benefit applicants. Still, patterns in the NHANES data of greater discordant results among females and non-Hispanic Black populations are worth noting and may indicate populations disproportionately impacted by choice of reference for PFT interpretation.

SUMMARY OF KEY POINTS

Chronic respiratory disorders can lead to significant impairment and disability. Although respiratory disorders in TGD populations and populations with VSTs are not well researched, existing data suggest that these populations may have a greater burden of respiratory disease.

Spirometry and DLCO are common PFTs that interpret lung function by comparing results against male and female reference ranges. For many applicants for disability benefits, PFTs can be appropriately compared against a reference range corresponding to a person’s sex recorded at birth. However, SSA’s disability criteria use the term “gender” in reference to PFTs, which may incorrectly indicate that “gender identity” is the determining factor in the interpretation of these measurements. SSA might consider changing the language in the respiratory disorder Listings to replace the word “gender” with “sex recorded at birth.” Making this change would allow for clearer assessment for some TGD applicants and some applicants with VSTs.9 Using the phrase “sex recorded at birth” rather than simply “sex” clarifies that sex as recorded at birth is the important patient characteristic for these specific assessments, not “sex” as may be recorded on other administrative records (e.g., driver’s license, passport).

For other applicants, sex recorded at birth may not be the appropriate reference sex for assessing pulmonary function, particularly for populations who began puberty-delaying medications and GAHT during puberty. Here, research suggests that “hormonal sex at puberty”—the hormone that was predominant during puberty (estrogen or testosterone) and influenced the shape and size of the thoracic cavity—may be a more accurate metric for choosing the PFT reference sex. For this portion of the population, affirmed gender—not sex recorded at birth—may be the more appropriate PFT reference sex.

However, it may be appropriate for providers to interpret PFT results against both reference sex ranges (“dual calculations”) to aid in clinical decision making for their patients, and SSA should be aware that it may receive medical records containing PFTs interpreted using both charts. SSA may also receive PFT calculations from both charts when providers were mistaken or lacked training and guidance on which chart to use. While considerable research is needed to determine best approaches, it is

___________________

9 The committee stresses that even though sex recorded at birth is important for the assessments listed here, this does not negate the importance of gender identity for disability applicants in general or for other types of disability assessments. In addition, the committee acknowledges that for some people with VSTs, sex assignment at birth (which becomes the sex recorded on birth certificates and medical records) may not be straightforward and can change after the initial determination.

the consensus of the committee, based on its clinical expertise and professional judgment, that when the medical record contains PFTs interpreted using both charts, SSA would best serve applicants who receive GAHT by using the lowest recorded spirometry or DLCO reading to determine the presence of disability. Given the unknowns as to how GAHT impacts lung function, such an approach would ensure appropriate adjudication for TGD people and people with VSTs10 who have not had access to providers trained to interpret their results thoughtfully and with consideration of their individual patient history.

Finally, use of chest binders is a common gender-affirming practice for TGD people assigned female sex at birth, as well as some people with VSTs. While minimal research exists on the impact of chest binders on pulmonary function, some patients may wear a chest binder during administration of a PFT. The medical record may not indicate whether a chest binder was worn during a PFT, but when the medical record contains different PFT values, SSA needs to be aware that those differences could be attributable to the fact that the patient wore a binder during one test but not another. For this reason and based on its clinical expertise and professional judgment, the committee concludes that SSA would best serve TGD applicants and applicants with VSTs by using the lowest recorded PFT value to determine disability under respiratory disorder Listings.

REFERENCES

Abid, S., S. K. Xie, M. Bose, P. W. Shaul, L. S. Terada, S. L. Brody, P. J. Thomas, J. A. Katzenellenbogen, S. H. Kim, D. E. Greenberg, and R. Jain. 2017. 17β-estradiol dysregulates innate immune responses to respiratory infection and is modulated by estrogen receptor antagonism. Infection and Immunity 85(10):e00422-17.

ALA (American Lung Association). 2023a. Introduction to pulmonary fibrosis. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/pulmonary-fibrosis/introduction#:~:text=What%20Is%20Pulmonary%20Fibrosis%3F,absorb%20oxygen%20into%20the%20bloodstream (accessed January 12, 2024).

ALA. 2023b. What is spirometry and why it is done. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests/spirometry (accessed March 12, 2024).

ALA. 2023c. Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/asthma/learn-about-asthma/types/asthma-copd-overlap-syndrome (accessed May 21, 2024).

ALA. 2024. Learn about bronchiectasis. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/bronchiectasis/learn-about-bronchiectasis (accessed January 12, 2024).

Al-Hadidi, N., and J. L. Baldwin. 2017. Spirometry considerations in transgender patients. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 139(2):sAB198.

___________________

10 Where people with VSTs take GAHT, the above approaches may be appropriate; however, research is limited on the impact of GAHT in populations with VSTs. The committee notes that people with VSTs take hormone therapy for a multitude of reasons beyond gender-affirming care and care is extremely individualized; the impact of various hormone therapies on sex-specific measurements is unknown.

Almqvist, C., M. Worm, and B. Leynaert. 2008. Impact of gender on asthma in childhood and adolescence: A GA2LEN review. Allergy 63(1):47–57.

Barnes, P. J. 2010. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Effects beyond the lungs. PLoS Medicine 7(3):e1000220.

Barnes, P. J. 2016. Sex differences in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mechanisms. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 193(8):813–814.

Basile, M. J., L. Dhingra, S. DiFiglia, J. Polo, R. Portenoy, J. Wang, P. Walker, B. Middour-Oxler, R. W. Linnemann, C. Kier, D. Friedman, M. Berdella, R. Abdullah, L. M. Yonker, M. Markovitz, D. Hadjiliadis, M. Shiffman, F. Fischer, S. Pollinger, M. Hardcastle, N. Chaudhary, and A. M. Georgiopoulos. 2023. Development of a cystic fibrosis primary palliative care intervention: Qualitative analysis of patient and family caregiver preferences. Journal of Patient Experience 10:e23743735231161486.

Becerra-Diaz, M., M. Song, and N. Heller. 2020. Androgen and androgen receptors as regulators of monocyte and macrophage biology in the healthy and diseased lung. Frontiers in Immunology 11:1698.

Boers, E., M. Barrett, J. G. Su, A. V. Benjafield, S. Sinha, L. Kaye, H. J. Zar, V. Vuong, D. Tellez, R. Gondalia, M. B. Rice, C. M. Nunez, J. A. Wedzicha, and A. Malhotra. 2023. Global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease through 2050. JAMA Network Open 6(12):e2346598–e2346598.

Bojesen, A., S. Juul, N. H. Birkebaek, and C. H. Gravholt. 2006. Morbidity in Klinefelter syndrome: A Danish register study based on hospital discharge diagnoses. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 91(4):1254–1260.

Bønnelykke, K., O. Raaschou-Nielsen, A. Tjønneland, C. S. Ulrik, H. Bisgaard, and Z. J. Andersen. 2015. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and asthma-related hospital admission. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 135(3):813–816.

Bradley, J. M., S. W. Blume, M.-M. Balp, D. Honeybourne, and J. S. Elborn. 2013. Quality of life and healthcare utilisation in cystic fibrosis: A multicentre study. European Respiratory Journal 41(3):571–577.

Cairns, C., and K. Kang. 2021. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2021 Emergency department summary tables. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2021-nhamcs-ed-web-tables-508.pdf (accessed February 29, 2024).

Carlson, C. S., M. Cushman, P. L. Enright, J. A. Caule, and A. B. Newman. 2001. Hormone replacement therapy is associated with higher FEV1 in elderly women. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 163(2):423–428.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2023a. 2020 healthcare use data. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/healthcare-use/2020/data.htm (accessed March 10, 2024).

CDC. 2023b. 2023 NHIS: National Health Interview Survey. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/2023nhis.htm (accessed March 10, 2024).

CFF (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation). n.d.-a. About cystic fibrosis. https://www.cff.org/intro-cf/about-cystic-fibrosis (accessed January 12, 2024).

CFF. n.d.-b. Living with advanced CF lung disease. https://www.cff.org/managing-cf/living-advanced-cf-lung-disease (accessed January 14, 2024).

Chalmers, J. D., A. B. Chang, S. H. Chotirmall, R. Dhar, and P. J. McShane. 2018. Bronchiectasis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 4(1):45.

Chichester, C. H., A. R. Buckpitt, A. Chang, and C. G. Plopper. 1994. Metabolism and cytotoxicity of naphthalene and its metabolites in isolated murine Clara cells. Molecular Pharmacology 45(4):664–672.

Chotirmall, S. H., S. G. Smith, C. Gunaratnam, S. Cosgrove, B. D. Dimitrov, S. J. O’Neill, B. J. Harvey, C. M. Greene, and N. G. McElvaney. 2012. Effect of estrogen on pseudomonas mucoidy and exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. New England Journal of Medicine 366(21):1978–1986.

Coakley, R. D., H. Sun, L. A. Clunes, J. E. Rasmussen, J. R. Stackhouse, S. F. Okada, I. Fricks, S. L. Young, and R. Tarran. 2008. 17β-estradiol inhibits Ca2+-dependent homeostasis of airway surface liquid volume in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Journal of Clinical Investigation 118(12):4025–4035.

Cortes-Puentes, G. A., C. J. Davidge-Pitts, C. A. Gonzalez, M. M. Dulohery Scrodin, C. C. Kennedy, and K. G. Lim. 2023. A 64-year-old patient assigned male at birth with COPD and worsening dyspnea while on estrogen and antiandrogen agents. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports 44:e101876.

de Marco, R., F. Locatelli, J. Sunyer, and P. Burney. 2000. Differences in incidence of reported asthma related to age in men and women. A retrospective analysis of the data of the European Respiratory Health Survey. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 162(1):68–74.

de Marco, R., G. Pesce, A. Marcon, S. Accordini, L. Antonicelli, M. Bugiani, L. Casali, M. Ferrari, G. Nicolini, M. G. Panico, P. Pirina, M. E. Zanolin, I. Cerveri, and G. Verlato. 2013. The coexistence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Prevalence and risk factors in young, middle-aged and elderly people from the general population. PLoS ONE 8(5):e62985.

de Souza, D. A. S., F. R. Faucz, L. Pereira-Ferrari, V. S. Sotomaior, and S. Raskin. 2018. Congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens as an atypical form of cystic fibrosis: Reproductive implications and genetic counseling. Andrology 6(1):127–135.

DeBoer, M. D., B. R. Phillips, D. T. Mauger, J. Zein, S. C. Erzurum, A. M. Fitzpatrick, B. M. Gaston, R. Myers, K. R. Ross, J. Chmiel, M. J. Lee, J. V. Fahy, M. Peters, N. P. Ly, S. E. Wenzel, M. L. Fajt, F. Holguin, W. C. Moore, S. P. Peters, D. Meyers, E. R. Bleecker, M. Castro, A. M. Coverstone, L. B. Bacharier, N. N. Jarjour, R. L. Sorkness, S. Ramratnam, A. M. Irani, E. Israel, B. Levy, W. Phipatanakul, J. M. Gaffin, and W. Gerald Teague. 2018. Effects of endogenous sex hormones on lung function and symptom control in adolescents with asthma. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 18(1):58.

Demko, C. A., P. J. Byard, and P. B. Davis. 1995. Gender differences in cystic fibrosis: Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 48(8):1041–1049.

Dragon, C. N., P. Guerino, E. Ewald, and A. M. Laffan. 2017. Transgender Medicare beneficiaries and chronic conditions: Exploring fee-for-service claims data. LGBT Health 4(6):404–411.

Dutton, L., K. Koenig, and K. Fennie. 2008. Gynecologic care of the female-to-male transgender man. Journal of Midwifery and Womens Health 53(4):331–337.

Fechter-Leggett, E. 2023. Selecting appropriate pulmonary function test reference sex for transgender and gender-diverse people. Paper presented to the National Academies Committee on Sex and Gender Identification and Implications for Disability Evaluation: Meeting 3, Washington, DC.

Fechter-Leggett, E., B. R. Ansell, R. Harvey, K. M. Kidd, and D. Weissman. 2022. Selecting appropriate pulmonary function test reference sex for transgender adults to address health disparities: Methods for data collection and interpretation. Poster presented at the American Thoracic Society 2022 International Conference, San Francisco, CA.

Foer, D. 2023. Selecting appropriate pulmonary function test reference sex for transgender and gender-diverse people. Paper presented to the National Academies Committee on Sex and Gender Identification and Implications for Disability Evaluation: Meeting 3, Washington, DC.

Foer, D., D. Rubins, A. Almazan, P. G. Wickner, D. W. Bates, and O. R. Hamnvik. 2021. Gender reference use in spirometry for transgender patients. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 18(3):537–540.

Fu, L., R. J. Freishtat, H. Gordish-Dressman, S. J. Teach, L. Resca, E. P. Hoffman, and Z. Wang. 2014. Natural progression of childhood asthma symptoms and strong influence of sex and puberty. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 11(6):939–944.

Fuseini, H., and D. C. Newcomb. 2017. Mechanisms driving gender differences in asthma. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 17(3):19.

Gaston, B., N. Marozkina, D. C. Newcomb, N. Sharifi, and J. Zein. 2021. Asthma risk among individuals with androgen receptor deficiency. JAMA Pediatrics 175(7):743–745.

Global Asthma Network. 2022. The global asthma report 2022. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 26(Supp 1):1–104.

Gómez Real, F., C. Svanes, E. H. Björnsson, K. A. Franklin, D. Gislason, T. Gislason, A. Gulsvik, C. Janson, R. Jögi, T. Kiserud, D. Norbäck, L. Nyström, K. Torén, T. Wentzel-Larsen, and E. Omenaas. 2006. Hormone replacement therapy, body mass index and asthma in perimenopausal women: A cross sectional survey. Thorax 61(1):34–40.

Graham, B. L., V. Brusasco, F. Burgos, B. G. Cooper, R. Jensen, A. Kendrick, N. R. MacIntyre, B. R. Thompson, and J. Wanger. 2017. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. European Respiratory Journal 49(1):e1600016.

Graham, B. L., I. Steenbruggen, M. R. Miller, I. Z. Barjaktarevic, B. G. Cooper, G. L. Hall, T. S. Hallstrand, D. A. Kaminsky, K. McCarthy, M. C. McCormack, C. E. Oropez, M. Rosenfeld, S. Stanojevic, M. P. Swanney, and B. R. Thompson. 2019. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update: An official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society technical statement. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 200(8):e70–e88.

Guo, J., A. Garratt, and A. Hill. 2022. Worldwide rates of diagnosis and effective treatment for cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 21(3):456–462.