Challenges in Supply, Market Competition, and Regulation of Infant Formula in the United States (2024)

Chapter: 5 2022 Infant Formula Shortage and Response

Chapter 5

2022 Infant Formula Shortage and Response

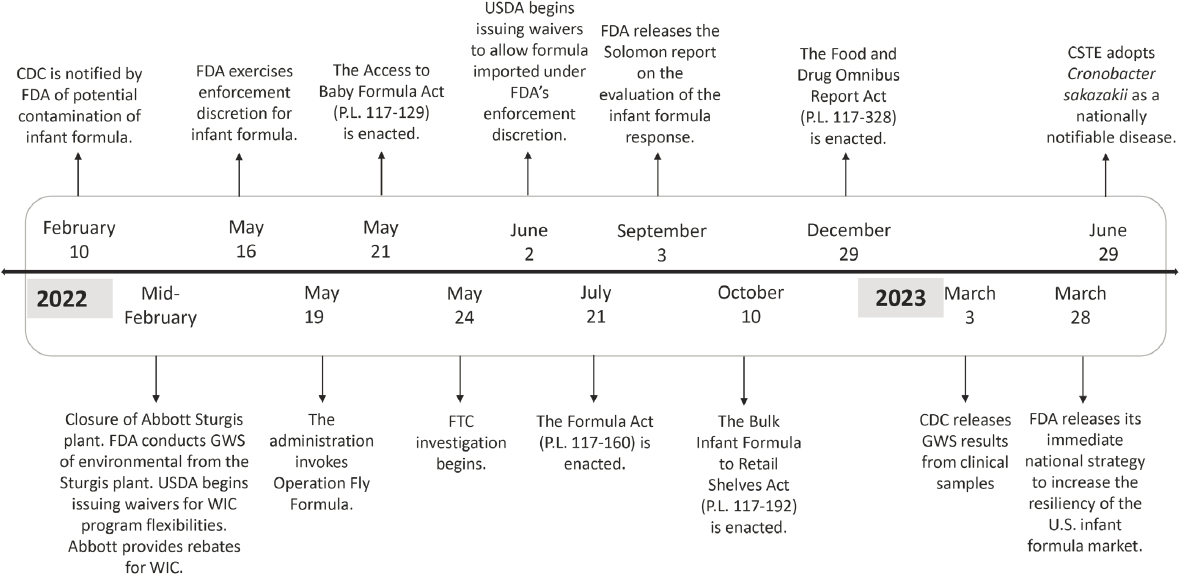

To identify areas where resiliency could be strengthened, the committee sought to understand how the infant formula supply chain changed in response to the infant formula shortage in 2022. To do this, the committee referred to information provided by stakeholders and developed a timeline of actions taken in response to the shortage (see Figure 5-1 and Appendix C). This chapter begins with an overview of the events that led to the 2022 infant formula shortage. The subsequent section describes the government’s response to the infant formula shortage. highlighting key actions and their significance, organized based on a timeline compiled by the committee. The chapter concludes with a characterization of the infant formula supply chain and a description of the demand for infant formula during and after the shortage.

EVENTS LEADING UP TO THE 2022 INFANT FORMULA SHORTAGE

In September 2021, a possible connection between bacterial infection caused by Cronobacter sakazakii and infant formula manufactured by Abbott Nutrition (Abbott) at a facility in Sturgis, Michigan, was reported to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) by a former employee at the plant that produced the contaminated infant formula (Rosa DeLauro, 2022). The report to FDA included the following allegations:

- Falsification of records relating to testing of seals, signing verifications without adequate knowledge, failure to maintain accurate maintenance records, shipping packages with fill weights lower than what was on the label;

- Releasing untested infant formula;

- Hiding information during a 2019 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) audit;

- Lax practices associated with clean-in-place procedures;

- Lack of traceability of the product;

- Failure to take corrective measures once the manufacturer knew its testing procedures were deficient; and

- An atmosphere of retaliation against any employee who raised concerns about manufacturer practices.

Following an FDA investigation and warnings about use of the infant formula produced by Abbott, FDA issued warnings and recommended that Abbott voluntarily recall powdered infant formulas produced in that facility (Abbott Nutrition, n.d., 2022a). Abbott, subsequently, implemented a recall of certain infant formula products and temporarily paused production at its Sturgis, Michigan facility, leading to a shortage of infant formula. The situation was made worse at Abbott because of a major rain event leading to flooding in Michigan along with power outages and water damage within the Sturgis facility, causing the plant to be shut down for a second time (Abbott Nutrition, 2022b; Reiley and Bella, 2022). Of note, the infant formula recall occurred against the background of ongoing supply chain challenges related to both the COVID-19 pandemic and areas of conflict around the world, which limited raw supplies for some components. In early to mid-2020, there were substantial shortages of many food products, including infant formula (Marino et al., 2023). Although it is not clear how much this situation may have driven later consumer response, it is likely that patterns of increasing purchases by consumers above short-term needs began in 2020.

Infant formula stockpiling contributed to the extent of the 2022 infant formula shortage. In May 2022, infant formula purchases began to spike above previous national averages (FDA, 2023a). The increase in purchasing resulted from both intentional and unintentional hoarding practices. Intentional stockpiling of infant formula was a theme identified by parents living through the shortage (Sylvetsky et al., 2024). In a national survey of 178 families that used infant formula during the shortage, 20 percent of families reported having 4 or more weeks of infant formula at home during that time (Damian-Medina et al., 2024). Inadvertent stockpiling was an unexpected outcome of reduced availability of smaller infant formula container sizes and manufacturing focus on larger tub

sizes (Damian-Medina et al., 2024; Sylvetsky et al., 2024). Larger tub sizes meant that, even with purchasing limits, consumers were able to purchase large amounts of infant formula at once.

Furthermore, families who only needed small amounts of infant formula (e.g., those who feed mostly breast milk with supplemental formula) were forced to buy more infant formula than needed. Inadvertent stockpiling was also an unexpected outcome from infant formula leftover after caregivers switched brands. Many families purchased several types of infant formula during the shortage because of gastrointestinal issues resulting from unexpected brand switching, causing an inadvertent “stockpiling” of unused formula. The commonality of this experience was evidenced by parental sharing of opened infant formula cans through informal networks (NASEM, 2023d; Sylvetsky et al., 2024).

The Role of Cronobacter sakazakii in Precipitating the 2022 Infant Formula Shortage

Cronobacter sakazakii contamination of powdered infant formula in the United States was an important factor in the development of the 2022 infant formula shortage. Cronobacter sakazakii is a gram-negative bacterium that produces a yellow pigment and ferments lactose, producing a gas during fermentation (Farmer, 2015). According to the Bacteriological Code, Cronobacter sakazakii was initially called Enterobacter sakazakii in 1980, but, as more information became available, a new genus, Cronobacter, was proposed to include Enterobacter sakazakii and other organisms (Farmer, 2015). The first documented cases of neonatal meningitis attributable to this organism were published in 1961 (Urmenyi and Franklin, 1961). Between 1961 and 2018, 183 unique infants with either bacteremia or meningitis from 24 countries were identified by a literature search,12 World Health Organization (WHO)/Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Strysko et al., 2020). The most common source of the infection was opened containers of powdered infant formula, and the case counts were significantly higher during the later years of the study (Strysko et al., 2020). CDC receives two to four reports of infant Cronobacter sakazakii infection each year; however, as it was not a notifiable disease in many states, the true incidence is not known (CDC, 2023a).

Cronobacter sakazakii is a serious, often deadly infection for infants younger than 2 months of age or who were born prematurely, as well as for the elderly and those who are immune suppressed (CDC, 2023a;

___________________

1 Meaning there is bacteria present in the blood (Smith and Nehring, 2017).

2 Inflammation of the membrane covering the brain and spinal cord (CDC, 2022a)

Strysko et al., 2020). Neonates can develop sepsis,3 meningitis, and necrotizing enterocolitis.4 Infants who develop meningitis and survive may experience lifelong neurological complications (Ling et al., 2022). Studies suggest that Cronobacter sakazakii has the ability to cross the intestinal and blood brain barrier, which allows for a potential path for infection of the central nervous system after ingestion (Almajed and Forsythe, 2016).

Cronobacter sakazakii is commonly found in the environment; on food preparation surfaces; on vegetable matter, meats, cheeses, and fish; in dried products such as teas, cereals, herbs, and spices; and in many other foods (CDC, 2023a; FDA, 2023b). As mentioned, Cronobacter sakazakii has been found in opened containers of powdered infant formula, as well as the apparatus used by mothers to pump breast milk (Bowen et al., 2017; Strysko et al., 2020). Cronobacter sakazakii cannot survive pasteurization, but it can survive spray drying (Arku et al., 2008), a process often used in the preparation of powdered infant formulas. It is possible for Cronobacter sakazakii to form a biofilm, which can become a significant problem if the biofilm occurs on the equipment used to process foods (Ling et al., 2020).

Because Cronobacter sakazakii is found in the environment, infant formula that does not undergo terminal pasteurization can become contaminated from the ingredients, from the processing plant itself, and from the employees (EFSA, 2004; Feder and Pugno, 1986). In addition, Cronobacter sakazakii may not be evenly distributed in a low-moisture product, such as powdered infant formula; as a result, a sample may test negative but still be contaminated (Arku et al., 2018; Jongenburger et al., 2011). Most recently, concern for contamination of powdered infant formula was noted in a plant where standing water was present in equipment that should have been dry (Berfield and Edney, 2022). Finally, powdered infant formula can become contaminated in the home environment once a can is opened, from surfaces or utensils used in preparing the infant formula (Bowen et al., 2016). Of note, Salmonella spp. contamination was also identified at the Sturgis plant, and these bacteria can affect infants of any age (Abbott Nutrition, 2022a).

U.S. GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO THE 2022 INFANT FORMULA SHORTAGE

This section includes a description of the actions taken by various government entities in response to the closure of the Abbott plant and

___________________

3 Sepsis occurs when chemicals released in the bloodstream to fight an infection trigger inflammation throughout the body (CDC, 2023b).

4 Inflammation of the intestine leading to bacterial invasion causing cellular damage and necrosis of the colon and intestine (Ginglen and Butki, 2024).

the infant formula shortage in 2022. The committee developed a timeline of key events (see Figure 5-1) based on information provided to the committee (see Appendix C).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

As soon as the initial illnesses were reported, CDC collaborated with FDA as appropriate on the investigation (CDC, 2022b; FDA, 2022b) analyzed infant formula samples from batches that were part of the Cronobacter sakazakii investigation, and in March 2023, CDC released results of genome-wide sequencing from the infected infants (CDC, 2022b; FDA, 2022b), and produced information that could be accessed directly by parents and repurposed by health care providers for dissemination to families (CDC, 2022c). CDC also provided advice for caregivers, provided information on Cronobacter sakazakii, and described the cases identified (CDC, 2022b).

Flexibilities Related to USDA Programs

Initial Response

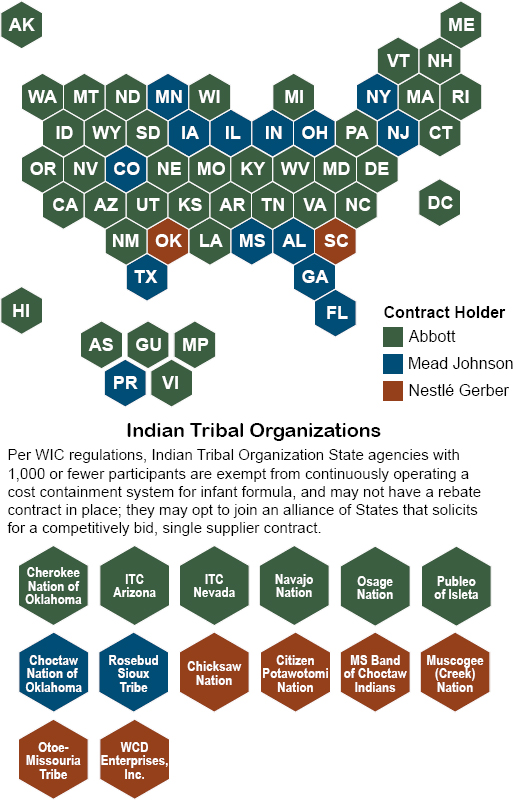

More than half of infant formula is consumed by participants in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service (FNS). Shortly after FDA notified USDA of the possibility of a disruption to the infant formula supply, USDA acted to mitigate the effect on WIC participants.

On February 18, 2022, the day after the recall was announced, USDA issued a series of resources, including a public-facing webpage on infant formula safety5 and guidance6 on returns and exchanges of recalled product, questions and answers about the recall, and information on how state WIC agencies could request waivers related to infant formula shortages (see Appendix C). Rules that could be waived included the requirement for medical documentation to issue non-contract non-exempt infant formula to healthy infants and requirements regarding the container sizes and amount of infant formula provided. USDA also issued a questions and answers document to help guide operators to support families with infants in the care of providers participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (USDA, 2022a).

___________________

5 https://www.fns.usda.gov/fs/infant-formula (accessed April 21, 2024).

6 https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/voluntary-recall-certain-abbott-powder-formulas (accessed April 21, 2024).

NOTES: CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CSTE = Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; FTC = Federal Trade Commission; GWS = genome-wide sequencing; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Waivers of Federal Regulations

For WIC participants to have access to the limited infant formula that was available during the shortage, flexibilities were needed with regard to WIC program rules and contract provisions requiring issuance of the contract brand of infant formula in specific container sizes and forms. On February 20, 2022, USDA began issuing waivers from three program rules (USDA, 2022b). These waivers were offered on a nationwide basis, but state WIC agencies had to seek a waiver and provide certain information in order to be considered (USDA, 2022c). The waivers allowed WIC-authorized vendors to exchange recalled infant formula for a different form, size, or brand; state WIC agencies to issue non-contract-brand infant formula to healthy infants without medical documentation; and state WIC agencies to issue infant formula to healthy infants in available container sizes, even if the total amount of infant formula exceeded the maximum monthly. Table 5-1 lists the number of waivers that were issued during the 2022 infant formula shortage.

On June 2, 2022, USDA began issuing waivers to allow state WIC agencies to issue infant formula imported under FDA’s enforcement discretion (see Appendix C). The requirement that infant formula be obtained from manufacturers registered with U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was waived, along with the minimum requirements and specifications for iron and caloric content, to allow state WIC programs to approve and issue products that have an iron level of at least 0.6 mg/100 mL and an energy level of at least 19 kcal/oz (USDA, 2022d).

Waivers to allow for product exchanges remained in effect through September 30, 2022 (USDA, 2022e). Waivers to allow for a non-contract brand of infant formula (including imported formula) for healthy infants remained in effect through February 28, 2023 (USDA, 2023a). Waivers regarding container sizes, amount of infant formula provided, and contract-brand imported formula for healthy infants remained in effect through April 30, 2023 (USDA, 2023a). Waivers related to container sizes or imported formula for infants with special medical needs remained in

TABLE 5-1 WIC Enforcement Discretion Waivers Issued in 2022

| Waivers | Number Issued |

|---|---|

| Maximum monthly allowance | 84 |

| Vendor exchanges | 83 |

| Medical documentation | 75 |

| Infant formula imported under FDA’s infant formula discretion | 72 |

| Vendor substitutions during transactions | 1 |

SOURCES: FNS response to committee questions (see Public Access File); USDA, 2024a.

effect through June 30, 2023 (USDA, 2023a). Products sold by companies that notified FDA of their intent to take steps for imported exempt infant formulas to remain on the U.S. market continue to be allowable within WIC through 2025. Table 5-1 describes the number of waivers that were issued during the 2022 infant formula shortage.

Prior to February 2022, USDA’s only WIC-related standing waiver authority was in the event of a major disaster declaration, which was authorized under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 USC § 5121-5207). In February 2022, USDA was able to use this authority because the major disaster declarations related to COVID-19 were in place nationwide. Had the shortage not occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, USDA would not have been able to issue waivers to respond to an infant formula recall and would not have had the authority to issue nationwide waivers (7 CFR § 246). In August 2022, USDA transferred the existing waivers to its new waiver authority under the Access to Baby Formula Act (ABFA) to allow them to remain in effect to provide state agencies with 60 days’ notice following the expiration of the major disaster declaration (USDA, 2022f).

Exempt infant formula for infants with special medical needs is not covered by WIC contracts and waivers were not needed to issue it, but state WIC agencies took steps to facilitate access to it. In June 2023, USDA sent a letter to state WIC agencies reminding them of ongoing flexibilities that did not require a waiver (USDA, 2023b). These included obtaining medical documentation by phone before obtaining it in writing to expedite issuance; encouraging health care providers to prescribe multiple WIC infant formulas; revising the WIC medical documentation form to list product-specific options (e.g., by creating a checklist of state-authorized infant formulas, including store brands); and establishing a way for health care providers to submit medical documentation to WIC directly (USDA, 2023b).

WIC Contract Flexibilities

State WIC infant formula contracts generally require WIC to issue only contract-brand non-exempt infant formula in specific container sizes and forms. Even if a state WIC agency has a waiver from federal rules, the contract must have a provision relaxing its usual constraints under specific circumstances to allow the issuance of infant formula in other container sizes, physical forms, or brands. Following the recall, Abbott agreed to relax these provisions in the contracts they held so those state WIC agencies could make use of federal waivers. These states also needed more non-exempt infant formula sold by other companies because, as described in Chapter 4, the WIC contract brand tends to dominate the

state market. Reckitt Benckiser-Meade Johnson (RBMJ) and Nestlé/Gerber sent some of their infant formula to alleviate the shortages.

States that held contracts with Nestlé/Gerber and RBMJ also experienced shortages (Stamm, 2022). While these companies were still obligated to provide infant formula under their WIC contracts, they had a financial incentive to send infant formula to states in which they did not hold the WIC contract where the state would pay the full wholesale price (and obtain a rebate from Abbott). When shortages emerged in the states contracting with Nestlé/Gerber and RBMJ, some of these WIC state agencies sought to issue non-contract-brand infant formula without medical documentation. To do so, they needed a waiver from USDA and also needed to make sure that it would be allowed under their infant formula contract. Some states had to modify their contracts to allow for this flexibility. In a May 2022 letter to state health commissioners, USDA encouraged state WIC agencies to work with their contract-holding manufacturer on flexibilities (USDA, 2022g).

WIC Infant Formula Costs

If state WIC agencies had to pay full price on non-contract infant formulas, their food costs would increase substantially, possibly jeopardizing their ability to serve all eligible families that sought to participate. Thus, a critical question was whether the state WIC agencies that had contracts with Abbott would receive rebates from Abbott if they issued another manufacturer’s infant formula. Although state infant formula contracts varied in their requirements, as soon as the recall was announced, Abbott began voluntarily providing rebates on non-contract-brand formulas to the state WIC agencies with which it held contracts (Abbott Nutrition, 2022c). USDA negotiated for an extension of the rebates at points when Abbott had announced they would end (Abbott Nutrition, 2022b), and they remained in place until January 31, 2023.

In contrast, however, when state WIC agencies that had contracts with RBMJ or Nestlé/Gerber received waiver and contract flexibility to issue non-contract infant formula, these companies did not provide rebates on the non-contract brands. The lack of rebates raised a concern for states about whether they would be permitted to use federal funding to cover the additional cost and whether sufficient federal funding was available. In the May 2022 letter to state health commissioners mentioned above, USDA clarified that state WIC agencies contracting with RBMJ and Nestlé/Gerber could use federal funds to cover the cost of issuing non-contract infant formula (USDA, 2022g). To contain costs, state WIC agencies used this flexibility on a limited basis.

At the time, WIC had sufficient funding to cover the cost of non-contract formula in these states on a temporary basis (USDA, 2022g). As a USDA representative shared with the committee, however, there is no guarantee that during a future shortage there would be sufficient funding available to cover the additional cost of providing the non-contract brand of infant formula in the absence of rebates. WIC’s $150 million contingency fund may be directed to state WIC agencies should participation or WIC food costs exceed current estimates or available funding and thus could be used during an infant formula shortage even though it was not needed in 2022. This funding remains available until expended but is not increased or replenished annually. As a result, USDA noted in a written response to a committee question: “We do not have certainty that the WIC Contingency Fund would be sufficient in amount or even available in a future shortage” (see Public Access File7). Thus, additional contingency funding could be needed to avoid putting eligible families on waiting lists during a shortage or proposals to reduce program costs by decreasing benefits or constraining eligibility would be needed. The president’s budget for fiscal year 2025 includes a proposal to establish an emergency contingency funding mechanism within the WIC program that would provide additional funding if food costs (or participation) exceed projections (USDA, 2024b). If adopted, this emergency funding would cover increased infant formula costs associated with an infant formula shortage.

FDA Enforcement Discretion

On May 16, 2022, FDA issued guidance to all manufacturers of infant formula explaining that it intended to use its enforcement discretion to increase the supply of infant formula in the United States to address the shortage (FDA, 2022c). The guidance explained that FDA would exercise enforcement discretion that applied to both domestic and imported new infant formulas that do not follow U.S. requirements (FDA, 2022c). While there were some instances in which FDA could not exercise enforcement discretion (e.g., nutrients are below the minimum required by 21 CFR § 107.100(a), one area in which FDA exercised enforcement discretion was for “minor labeling issues” (FDA, 2022c), such as if an infant formula label did not list the nutrients in the order required by FDA regulations (FDA, 2022c).

FDA temporarily exercised this enforcement discretion on a case-by-case basis in order to increase supply and simultaneously protect the

___________________

7 Public Access File available by request via the National Academies. https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/challenges-in-supply-market-competition-and-regulation-of-infant-formula-in-the-united-states (accessed April 11, 2024).

health of infants (FDA, 2023c). Twenty-two non-exempt infant formulas (from the United Kingdom, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, Singapore, and Spain) made by eight companies (two of which already operate in the United States) received a letter of enforcement discretion (FDA, 2023c). Seven exempt infant formulas (from Mexico, Spain, and the Netherlands) made by six companies received a letter of enforcement discretion, with two of the six companies currently operating in the United States (FDA, 2023c). The guidance document noted that the enforcement discretion would remain in effect until November 14, 2022 (FDA, 2022c).

In September 2022, FDA, in updated guidance, noted that companies that received a letter of enforcement discretion could continue to sell infant formula in the United States, as long as they took actions to achieve compliance with the statutory and regulatory requirements by October 18, 2025 (FDA, 2022c,d). This updated guidance also indicated that companies that had not received a letter of enforcement discretion from FDA could continue to seek FDA review in accordance with FDA regulations (FDA, 2022d).

Operation Fly Formula

On May 19, 2022, the White House announced that it would begin transporting infant formula from other countries into the United States (U.S. Embassy, 2022). The infant formula importation was referred to broadly as “Operation Fly Formula” and initially focused on exempt infant formulas but quickly moved to include non-exempt infant formulas (White House, 2022). In addition, tariffs on infant formula were removed at that time. The tariffs were reinstated in January (Boehm, 2023).

Access to Baby Formula Act

On May 21, 2022, the bipartisan ABFA (P.L. 117-129) was enacted. In June 2022, USDA implemented the ABFA provisions with a letter to WIC state agencies (USDA, 2022h). In December 2023, USDA published a final rule, which took effect on February 12, 2024, specifying in more detail how the ABFA would be implemented.

WIC Provisions

The legislation included several WIC-related provisions. First, the ABFA created a standing waiver authority to be used to address a supply chain disruption or emergency. The waiver authority covered regulatory provisions that had been waived during the 2022 infant formula shortage—

regarding returns and exchanges; medical documentation for non-contract, non-exempt infant formula for healthy babies; container sizes; and monthly allowances. It also allowed for waivers of other provisions, as needed, to provide WIC benefits, so long as the waiver does not substantially weaken the nutritional quality of the foods provided by WIC. Waivers last for up to 45 days, with extensions requiring at least 15 days’ notice, and ending no later than 60 days after the end of a supply chain disruption or emergency.

Second, the ABFA required USDA and HHS to enter into a formal agreement to facilitate communication and coordination regarding supply chain disruptions, including recalls.

Third, the ABFA requires each state WIC agency’s infant formula contract to include “remedies in the event of an infant formula recall, including how an infant formula manufacturer would protect against disruption to program participants in the State” (USDA, 2022i). Through the Final Rule published on December 23, 2023, USDA established more specific implementation requirements. The state WIC agency had to be the entity to determine when remedies take effect and remain in effect. In addition, each state’s infant formula contract had to include certain provisions and may include additional remedies to protect WIC participants. These remedies included allowing infant formula to be issued in all unit sizes, even if they exceed the maximum monthly allowance (but the state WIC agency and infant formula manufacturer had to prioritize unit sizes that most closely provide the maximum monthly allowance); and allowing non-contract-brand infant formula to be issued without medical documentation to infants.

The Final Rule also required the company of any contract-brand infant formula that is subject to a recall, to provide an action plan that includes supply data within a time frame established within the contract to meet infant formula demand and limit the disruption to WIC participants, and to pay rebates on competitive, non-contract-brand infant formula.

The requirement for an infant formula manufacturer to pay rebates on competitive, non-contract infant formula when its products are subject to a recall is particularly important. As described above, during the 2022 Abbott recall, Abbott voluntarily provided rebates on non-contract infant formula when it was available to WIC participants. Requiring such payments instead of relying on voluntary action by companies puts USDA and state WIC agencies in a better position to respond to future recalls.

Bidder Requirements

Although not addressed in the ABFA, USDA’s implementing Final Rule changed the requirements regarding bidders on infant formula WIC

contracts. To bid, the Final Rule required infant formula companies to register with HHS, certify that their infant formulas comply with FDA regulations, and be “responsive” (see Chapter 4 for USDA definition of responsive). Through ABFA rulemaking, USDA eliminated the requirement that bidders be “responsive,” which also eliminated the opportunity for state WIC agencies to establish technical requirements related to resiliency or quality.

Emergency Preparedness

The ABFA implementing rule also required state WIC agencies to include an emergency preparedness plan, referred to as a plan for alternative operating procedures, in their state WIC plan. The alternative operating procedure plans are required to meet the criteria in 7 C.F.R. § 246.4(a)(30), including adjustments to certification, benefits, food package issuance, and vendor requirements; a procedure to ensure continuity of services for especially vulnerable participants; a communications plan; and a plan for working with emergency planning and response agencies covering the state. USDA’s 2021 Guide to Coordinating Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Services When Regular Operations Are Disrupted (2021 USDA Guide; USDA, 2021) has not been updated since the shortage to fully incorporate these changes. Both the 2021 USDA Guide and requirements regarding state alternative operating procedure plans lack guidance for how USDA and states should design a governance structure for crisis response that clearly articulates all private-sector stakeholders, civil society stakeholders, and government agencies that need to be involved; what is expected of them; and how the response will be coordinated at the state level. Such governance structures and accompanying dashboards for crisis management were suggested in other contexts (e.g., COVID-19 testing) (Anupindi et al., 2020). Moreover, there is no template or infrastructure for a dashboard for WIC staff to track critical data on the supply and shortages of infant formula at the state level. There is also a lack of guidance for states that lack infrastructure to build a data analytics team to track product availability at WIC-authorized vendors.

In addition, current plan protocols (including those related to 7 CFR § 246.12) emphasized the provision of information about supply from the contract manufacturer and information about demand from vendors to the state WIC agency. However, a distributor may serve a region that includes multiple states and territories, complicating this provision of information to state WIC agencies. In addition, manufacturers may not

be cognizant of final points of sale, since in some cases that decision is made by a wholesaler or distributor. Even large vendors do not always realize when their in-house distributor routes product to one state, leaving shelves bare in another WIC contract state. Currently, under 7 CFR § 246.12, vendors are not required or encouraged to provide information about which wholesaler or distributor they use to supply WIC state or territory agencies, nor are they required to notify WIC agencies in the event of an unusual increase in sales or decrease in product availability in real time.

During the shortage, state WIC agencies reported sending staff to individual retail sites to determine where products were in short supply, exacerbating staffing shortages (NASEM, 2023a).

Federal Trade Commission Investigation

On May 24, 2022, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) launched an investigation into the infant formula shortage (FTC, 2022a). FTC took three steps to examine and address any anticompetitive, unfair, or deceptive acts or practices that contributed to or exacerbated the infant formula shortage (FTC, 2022b). First, FTC investigated and took enforcement actions against persons that deceived, exploited, or scammed American families trying to buy infant formula. Second, it examined whether infant formula manufacturers and distributors were “engaging in unlawful forms of economic discrimination” that may have been “limiting the availability of formula at certain retailers.” Third, FTC issued a request for public comments on “factors that contributed to the shortage or hampered our ability to respond to it.” As part of this effort, FTC noted it would work with USDA to determine if any changes to WIC policy may be “necessary to promote competition and resiliency in the infant formula market to prevent future shortages” (FTC, 2022c). FTC solicited comments from the public on factors that may have contributed to the shortage and other relevant topics (see Box 5-1) (FTC, 2022c).8 FTC released the results of their investigation on March 13, 2024 (FTC, 2024). The FTC report did not make specific recommendations, but observed generally the level of concentration in the infant formula market and explored whether policy changes had the potential to promote greater resiliency in the marketplace (FTC, 2024).

Formula Act and Bulk Infant Formula to Retail Shelves Act

On July 21, 2022, the Formula Act (P.L. 117-160) was enacted in an attempt to encourage more imports of infant formula ingredients and final

___________________

8 https://www.regulations.gov/docket/FTC-2022-0031 (accessed April 21, 2024).

BOX 5-1

Topics on Which the Federal Trade Commission Solicited Public Comment During Their Investigation

- Instances where families have experienced fraud, deception, or scams when attempting to purchase infant formula

- Instances where families have been forced to purchase infant formula from online resellers at exorbitant prices

- Whether families purchasing infant formula through WIC have faced additional difficulties compared to non-WIC purchasers

- Retailers’ experiences with extremely large purchases of infant formula in excess of a single family’s needs for the purpose of long-term stockpiling or resale

- Retailers’ experiences working with infant formula distributors and manufacturers throughout the Abbott recall and ensuing infant formula supply disruption

- Retailers’ experiences obtaining brands of infant formula that are not ordinarily covered by their state’s WIC program

- Whether small and independent retailers have faced particular difficulties accessing limited supplies of infant formula, especially relative to large chain retailers

- The impact of mergers and acquisitions on the number of infant formula suppliers, capital investment, and total manufacturing capacity

- The impact of state WIC competitive bidding on the number of infant formula suppliers, capital investment, and total manufacturing capacity

- The impact of FDA regulations on the number of infant formula suppliers, capital investment, and total manufacturing capacity, including [those] located outside the United States

- Whether regulatory barriers have prevented companies located outside the United States from entering the infant formula market

- Whether barriers have prevented new companies from entering WIC

SOURCE: Text for this box is directly from FTC, 2022c.

product into the United States. The law temporarily suspended the 17.5 percent tariff on imports of infant formula. The Bulk Infant Formula to Retail Shelves Act (P.L. 117-192), which was enacted on October 10, 2022, expanded a limiting quota on tariffs on imports of bulk infant formula base powders and suspended the tariff of $1.035/kg plus 13.6 percent between October 13, 2022, and December 31, 2022 (CBP, 2022). Base powders are a key input into the manufacture of infant formula, requiring only the addition of nutrients and other additives to be transformed into the final product. Reducing tariffs on this input was intended to encourage increases in domestic manufacture of infant formula (Larson, 2022).

The tariff waivers took months to put in place. The suspension of tariffs may have helped mitigate costs during the shortage, but, as already discussed, the Congressional Research Service noted that tariffs were

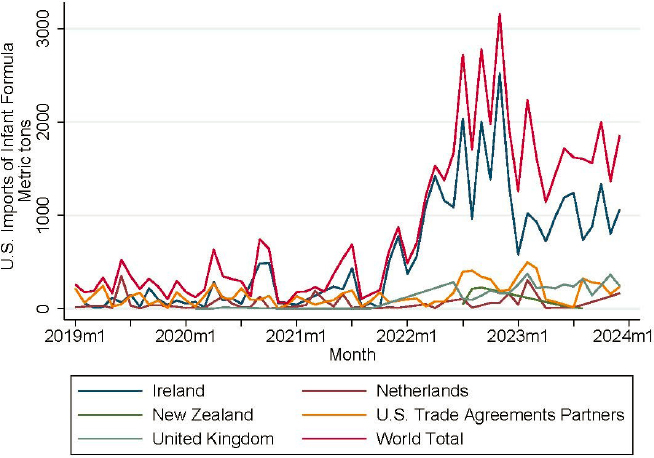

not likely the main factors limiting imports at the onset of the shortage (CRS, 2022). They noted in late May 2022 that imports from Ireland had increased faster than imports from U.S. free trade area partners and suggest instead that non-tariff barriers in the form of regulations likely played a role. Figure 5-2 shows U.S. imports of infant formula (products for infants ages 0–12 months only) from various country sources.

While imports from an FDA-registered plant in Ireland did spike briefly during the summer that tariffs were suspended, they began rising months before the suspension of tariffs. The differential between imports from Ireland and imports from U.S. trade agreement partners does not appear to be driven for any extended period by the suspension of tariffs. The suspension of tariffs in late July 2022 may have encouraged slightly higher imports from New Zealand. To the degree that non-tariff barriers, such as quality factors, may be the primary limiting factors, the sudden and temporary suspension of these non-tariff barriers (as through FDA enforcement discretion) could be too short-lived to justify a shift in the

NOTE: Tariff codes for infant formula (0–12 mos only): HTSUS codes 1901.10.05, 1901.10.10, 1901.10.11, 1901.10.15, 1901.10.16, 1901.10.21, 1901.10.26, 1901.10.29, 1901.10.30, 1901.10.31, 1901.10.33, 1901.10.35, 1901.10.36, 1901.10.40, 1901.10.41, 1901.10.44, 1901.10.45, 1901.10.49, 1901.10.55, 1901.10.60, 1901.10.75, 1901.10.80, 1901.10.85, 1901.10.90, 1901.10.95.

SOURCE: Calculations from U.S. Bureau of the Census USA trade data.

long-term output for exports of infant formula to the United States from New Zealand (Moodie, 2022).

To increase imports into the United States in 2022, FDA used enforcement discretion and the White House airlifted product into the country (FDA, 2022c; White House, 2022). These conditions are an indication that during normal times, trade barriers prevent formula produced in other countries from entering the U.S. market.

The very small percentage of imported formula consumed in the United States combined with the difficulty that manufacturers, retailers, and the U.S. government faced when the need to bring more formula into the country was acute implies that the U.S. infant formula market can be characterized as almost completely closed to imports owing to extremely high trade barriers, a condition economists call autarky.9

It is plausible that prior to the shortage, tariffs may have deterred some overseas producers from undertaking large, fixed costs involved in getting necessary approvals to export to the United States, making it harder to pivot to these products when urgently needed. However, the Congressional Research Service concluded that tariffs did not seem to be the major barrier keeping infant formula from entering the United States during the crisis, noting that imports from Ireland which face the full tariff grew faster than imports from Chile and other free trade partners that face no tariffs (CRS, 2022). Therefore, the general tariffs (of under 20 percent) on the final product are not likely, by themselves, to have been a prohibitive factor for imports during shortage. Reducing tariffs during the shortage may have helped prevent or mitigate some increases in costs to consumers.

Actions by the FDA Commissioner

Evaluation of Infant Formula Response

In September 2022, Dr. Steven Solomon,10 director of FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine, released his internal agency review of the response to the 2022 infant formula shortage in response to FDA Commissioner Dr. Robert Califf’s May 25, 2022, request (FDA, 2022a). Dr. Solomon’s report included five major areas of need within his findings and recommendations for FDA (see Box 5-2). In December 2023, FDA provided an update

___________________

9 https://www.britannica.com/money/autarky (accessed April 21, 2024).

10 Dr. Solomon previously worked in the Office of Regulatory Affairs which houses the inspectional programs and he was not involved in from day-to-day activities of the offices/centers directly involved in the response.

BOX 5-2

Major Areas of Need Identified by Dr. Solomon in His Evaluation of FDA’s Response to the 2022 Infant Formula Shortage

- Modern information technology that allows for the access and exchange of data in real time to all the people involved in response.

- Sufficient staffing, training, equipment, and regulatory authorities to fulfill the FDA’s mission.

- Updated emergency response systems that are capable of handling multiple public health emergencies occurring simultaneously.

- Increased scientific understanding about Cronobacter, its prevalence and natural habitat, and how this translates into appropriate control measures and oversight.

- Assessment of the infant formula industry, its preventive controls, food safety culture and preparedness to respond to events.

SOURCE: Text for this box is directly from FDA, 2022a.

on its actions to strengthen supply chain resiliency in response to the evaluation (FDA, 2023b).

Reagan-Udall Foundation Report and FDA Reorganization

On December 6, 2022, an independent expert panel, convened and facilitated by the Reagan-Udall Foundation at the request of FDA Commissioner Dr. Califf in July 2022, submitted its report, Operational Evaluation of the FDA Human Foods Program, to FDA (Reagan-Udall Foundation, 2022). The aim of Dr. Califf’s request was to evaluate ways to strengthen FDA’s food regulatory role. The report produced a set of recommendations on how to move toward a more enabling and effective culture; change the structure within FDA to address challenges facing the Human Foods Program; increase and expand its financial, personnel, and technological resources; and it suggested new authorities that could strengthen the Human Foods Program (Reagan-Udall Foundation, 2022).

Following the release of the report, in January 2023, FDA announced it would develop a proposal to create a unified Human Foods Program and new Office of Regulatory Affairs. The proposal was released, and

as of December 2023, was under review by the Secretary of HHS (FDA, 2023d,e).11 The Unified Foods program areas include:

food safety, chemical safety and innovative food products, including those from new agricultural technologies, that will bolster the resilience of the U.S. food supply in the face of climate change and globalization, as well as nutrition to help reduce diet-related diseases and improve health equity. (FDA, 2023f)

Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022

On December 29, 2022, the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022 (FDORA) as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 (P.L. 117-328) was enacted (see Box 5-3). Each provision is described in more detail below.

Section 3401, “Protecting Infants and Improving the Formula Supply,” of FDORA amended the Infant Formula Act to require FDA to review the nutrients in infant formula “every 4 years as appropriate” (21 USCS § 350(a)(i)). Congress additionally authorized FDA to “revise the list of nutrients and the required level for any nutrient” in accordance with its findings from the review (21 USCS § 350a(i)). During such review, FDA is required to “consider any new scientific data or information related to infant formula nutrients, including international infant formula standards” (21 USCS § 350a(i)).

BOX 5-3

Key Provisions in the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022 Relating to Infant Formula

- Amended Infant Formula Act to address issues related to the 2022 infant formula shortage;

- Set forth new requirements related to disruptions, recalls, and shortages;

- Established critical foods which includes infant formula;

- Required FDA to establish an Office of Critical Foods within the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition; and

- Established new reporting requirements related to infant formula

SOURCE: Text for this box is drawn from P.L. 117-328.

___________________

11 As of May 30, 2024, the reorganization has been approved and implementation will begin on October 1, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fdas-reorganization-approved-establishing-unified-human-foods-program-new-model-field-operations-and (accessed June 3, 2024).

In several provisions of FDORA, Congress required consideration of international standards. In one provision, FDORA requires the Secretary of HHS to meet with “representatives from other countries to discuss methods and approaches to harmonizing regulatory requirements for infant formula, including with respect to … nutritional requirements” (21 USCS § 350a-1(f)).

FDORA also amended the Infant Formula Act to require FDA to submit an annual report to Congress providing the following information for foreign and domestic manufacturers and facilities: the number of new infant formula submissions received in the preceding calendar year; the “number of such submissions that included any new ingredients that were not included in any infant formula already on the market”; and the number of and time between inspections and reinspections conducted by or on behalf of FDA to evaluate compliance with the requirements for infant formulas related to good manufacturing practices and quality control procedures (21 USCS § 350a(1)).12

Recalls

FDORA also amended the Infant Formula Act’s provisions related to recalls. The amendment included a provision requiring FDA to “submit to the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions of the Senate and the Committee on Energy and Commerce of the House of Representatives a notification of [an infant formula] recall” within 24 hours of such recall (21 USCS § 350a(k)).

In a section that sunsets on September 30, 2026, FDORA also required the manufacturer of a recalled infant formula to submit a plan of action to FDA “promptly” after the initiation of the recall. The manufacturer’s plan of action must include an estimated timeline and the actions it will take “suited to the individual circumstances of the particular recall”; identification and plan to address “any cause of, and contributing factor in, known or suspected adulteration or known or suspected misbranding; and if appropriate, to restore operation of the impacted facilities” (21 USCS § 350a-1(h)).

In the same section, FDORA requires that if an infant formula recall “impacts over 10 percent of the production of the infant formula intended for sale in the United States,” the manufacturer must submit “a plan to

___________________

12 In 1982, FDA promulgated regulations on Infant Formula Requirements Pertaining to Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Quality Control Procedures, Quality Factors, Records and Reports, and Notification (21 CFR § 106). The good manufacturing practices are designed to ensure that infant formula provides the required nutrients and “is manufactured in a manner designed to prevent adulteration of the infant formula” (21 USCS § 350a(b)).

backfill the supply of the manufacturer’s infant formula supply if the current domestic supply of such infant formula has fallen, or is expected to fall, below the expected demand for the formula” (21 USCS § 350a-1(h)). After submission of the plan of action, FDA shall promptly submit a report to the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions of the Senate and the Committee on Energy and Commerce of the House of Representatives (21 USCS § 350a-1(h)). The report must include “information concerning the current domestic supply of infant formula, including a breakdown of the specific types of formula involved; and an estimate of how long current supplies will last.” If the recall will affect more than 10 percent of the domestic production of infant formula intended for sale in the United States, FDA’s report must additionally include “actions to work with the impacted manufacturer or other manufacturers to increase production,” “any additional authorities needed regarding production or importation to fill a supply gap, and any supplemental funding necessary to address the shortage” (21 USCS § 350a-1(h)). This provision also sunsets on September 30, 2026.

FDORA’s new provisions require FDA to complete an inspection of an infant formula manufacturing facility “impacted by a recall” (21 USCS § 350a-1(i)). FDA must also provide the manufacturer a list of actions necessary to “address deficiencies contributing to the potential adulteration or misbranding of product at the facility, and safely restart production at the facility” (21 USCS § 350a-1(i)). The manufacturer must provide a “written communication” to FDA listing the “corrective actions to address manufacturing deficiencies identified” during the facility inspection. A time frame for the manufacturer’s written communication is not clearly written into the law and may be an area for FDA regulation; however, within 7 days of FDA receiving the manufacturer’s written response, FDA must “provide a substantive response to such communication concerning the sufficiency of the proposed corrective actions” (21 USCS § 350a-1(i)). FDORA states that if a reinspection is required “to ensure that such manufacturer completed any remediation actions or addressed any deficiencies,” FDA “shall reinspect such facility in a timely manner” (21 USCS § 350a-1(i)). Importantly, FDORA requires HHS to “prioritize and expedite an inspection or reinspection of an establishment that could help mitigate or prevent a shortage of an infant formula” (21 USCS § 350a-1(i)).

Inspections

In terms of standard inspections, FDORA clarified that “in accordance with a risk-based approach,” FDA must “conduct inspections, including unannounced inspections, of the facilities (including foreign facilities) of

each manufacturer of an infant formula” not less than one time per calendar year (21 USCS § 350a-1(i)). FDA is also required to “ensure timely and effective internal coordination and alignment among” its Office of Regulatory Affairs and Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

Regarding foreign infant formula manufacturing facilities, FDORA requires the Secretary of HHS to meet with “representatives from other countries to discuss methods and approaches to harmonizing regulatory requirements for infant formula, including with respect to inspections” (21 USCS § 350a-1(f)). Moreover, FDA is permitted to “rely on inspections conducted by foreign regulatory authorities, under arrangements or agreements, and conducted by state agencies under contract, memoranda of understanding, or any other obligation” (21 USCS § 350a-1(i)). FDORA also permits FDA to “recognize the inspection of foreign establishments that manufacture infant formula for export to the United States” through agreements or arrangements with foreign governments (21 USCS § 350a-1(f)).

National Strategies

FDORA also requires both the U.S. government and infant formula manufacturers to create strategies to protect the infant formula supply chain. Congress required the Secretary of HHS, in consultation with other departments and agencies, including USDA, to develop and issue

a national strategy on infant formula to increase the resiliency of the infant formula supply chain, protect against future contamination and other potential causes of supply disruptions and shortages, and ensure parents and caregivers have access to infant formula and information they need. (21 USCS § 350a-1(j))

The law required development of both immediate and long-term national strategies.

FDA’s immediate strategy must increase resiliency of the infant formula supply chain by

- “assessing causes of any supply disruption or shortage of infant formula in existence as of [December 29, 2022] and potential causes of future supply disruptions and shortages;

- assessing and addressing immediate infant formula needs associated with the shortage; and

- developing a plan to increase infant formula supply, including through increased competition” (21 USCS § 350a-1(j)).

In addition, the immediate strategy must “ensure the development and updating of education and communication materials for parents and caregivers that cover

- where and how to find infant formula,

- comparable infant formulas on the market,

- what to do if a specialty infant formula is unavailable,

- safe practices for handling infant formula, and

- other topics, as appropriate” (21 USCS § 350a-1(j)).

FDORA required that FDA publish a list on its website “providing information on how to identify appropriate substitutes for infant formula products in shortage that are relied upon by infants and other individuals with inborn errors of metabolism or other serious health conditions” (21 USCS § 350a-1(e)).

FDORA also required FDA to create, following the submission of this report, a long-term strategy “to improve preparedness against infant formula shortages” by

outlining methods to improve information-sharing between the federal government and state and local governments, and other entities as appropriate, regarding shortages; recommending measures for protecting the integrity of the infant formula supply and preventing contamination; outlining methods to incentivize new infant formula manufacturers to increase supply and mitigate future shortages; and recommending other necessary authorities to gain insight into the supply chain and risk for shortages, and to incentivize new infant formula manufacturers. (21 USCS § 350a-1(j))

Personal Importation

FDORA provided a 90-day window during which an individual was able to “import up to a 3-month supply of infant formula for personal use” without “prior notice” to FDA (21 USCS § 350a-1(m)). The 90-day window commenced on December 29, 2022, when FDORA was enacted (21 USCS § 350a-1(m)). Such infant formula was required to be “exclusively for personal use,” meaning it would “not be commercialized or promoted,” and did “not present an unreasonable risk to human health” (21 USCS § 350a-1(m)). FDORA permitted such importation from Canada, any country in the European Union, and “any other country that is determined by [FDA] to be implementing and enforcing requirements for

infant formula that provide a similar assurance of safety and nutritional adequacy as the requirements” of the FDCA (21 USCS § 350a-1(m)).

FDORA stated that “persons considering the personal importation of infant formula should consult with their pediatrician about such importation” (21 USCS § 350a-1(m)). Moreover, the law required that if a “health care provider becomes aware of any adverse event,” which they “reasonably” suspect was associated with infant formula imported by consumers for personal use, the health care provider “shall report such adverse event” to FDA (21 USCS § 350a-1(m)). While during the shortage, FDA exercised enforcement discretion for imported infant formulas entering interstate commerce, this authority is separate from personal importation by consumers.

FDORA also required FDA to post on its website information for consumers, including that infant formula imported for personal use may not have been manufactured in a facility that has been inspected by FDA, the labeling of such infant formula “may not meet the standards and other requirements” applicable to infant formula under the FDCA, and that the nutritional content of such infant formula “may vary from that of infant formula meeting such standards and other requirements” (21 USCS § 350a-1(m)).

Labeling

FDORA required the Secretary of HHS to participate in meetings with representatives from other countries to discuss methods and approaches to harmonize regulatory requirements, including labeling requirements (21 USCS § 350a-1(f)).

Office of Critical Foods

FDORA established a new category of food, “critical foods” (21 USCS § 350a-1), which includes infant formula and medical foods, as defined in section 5(b)(3) of the Orphan Drug Act. FDORA required FDA to establish an Office of Critical Foods to be responsible for oversight, coordination, and facilitation of activities related to critical foods (21 USCS § 350a-1). As of May 2024, FDA had started the process of establishing an Office of Critical Foods within the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (FDA, 2023e).

Meaningful disruptions

New requirements for critical food include provisions relating to the “meaningful disruption” of the infant formula supply. Meaningful disruption is defined as “a change in production that is reasonably likely to lead to a significant reduction in the supply of a

critical food by a manufacturer that affects the ability of the manufacturer to meet expected demand for its product” (21 USCS § 350m(a)(4)(A)). The law considers both “interruptions” and “permanent discontinuations” to be meaningful disruptions. The law also clarifies that “meaningful disruptions” do not include disruptions caused by routine maintenance issues or those caused by “changes or discontinuance of flavors, colors, or other insignificant formulation characteristics, or insignificant changes in manufacturing so long as the manufacturer expects to resume operations in a short period of time” (21 USCS § 350m(a)(4)(B)).

In case of a meaningful disruption in the infant formula supply, such as through interruption or permanent discontinuance of the manufacture of a critical food, the manufacturer must notify FDA “as soon as practicable, but not later than 5 business days after such discontinuance or such interruption” (21 USCS § 350m(a)(1)). Within 5 calendar days of receiving this notification, if FDA determines the disruption resulted in, or is likely to result in, a shortage of a critical food, FDA shall distribute information on such shortage to the Secretary of Agriculture and “to the maximum extent practicable to the appropriate entities, as determined by the Secretary” (21 USCS § 350m(a)(2)). This information distribution date triggers additional measures. FDORA amended the Infant Formula Act to require FDA to waive the 90-day premarket notification requirement “and apply a 30-day premarket submission requirement” to the introduction of, or delivery for introduction of, any new infant formula into interstate commerce to commence on this information distribution date (21 USCS § 350a(j)). The waiver of the 90-day premarket notification must remain in effect for 90 days from the information-distribution-date, or “such longer period” as FDA determines is appropriate, “to prevent or mitigate a shortage of infant formula” (21 USCS § 350a(j)).

To further reduce any negative effects of any future disruption, FDORA further amended the Infant Formula Act to allow FDA to “waive any requirement” under the Infant Formula Act “to facilitate the importation of [exempt] infant formula” during a shortage of [exempt] infant formula (21 USCS § 350a(m)). FDORA suggests that such a waiver “may be applicable to (A) the importation of [exempt] infant formula from any country” that is determined by FDA to be “implementing and enforcing requirements for infant formula that provide a similar assurance of safety and nutritional adequacy as the requirements” of the Infant Formula Act; or (B) “the distribution and sale of such imported [exempt] infant formula” (21 USCS § 350a(m)).

Redundancy risk management plans

FDORA also requires each manufacturer of critical foods to “develop, maintain, and implement, as appropriate, a redundancy risk management plan that identifies and evaluates

risks to the supply of the food, as applicable, for each establishment in which such food is manufactured” (21 USCS § 350m(b)). The law suggests that the risk management plan “may identify and evaluate risks to the supply of more than one critical food, or critical food category, manufactured at the same establishment” and “may identify mechanisms by which the manufacturer would mitigate the impacts of a supply disruption through alternative production sites, alternative suppliers, stockpiling of inventory, or other means” (21 USCS § 350m(b)). FDA may inspect this plan under its authority to inspect factories, warehouses, establishments, and vehicles for the introduction of infant formula into interstate commerce, which includes providing FDA with access to relevant records (21 USCS § 374).

In November 2023, FDA shared information on the new requirement for manufacturers of a critical food to develop a redundancy risk management plan (FDA, 2023g,h), as required by FDORA. FDA repeated FDORA’s requirements in a resource for industry, stating that the risk management plan may

identify and evaluate risks to the supply of one or more critical food, or critical food category, manufactured in the same establishment; and identify mechanisms by which the manufacturer would mitigate the impacts of a supply disruption through alternative production sites, alternative suppliers, stockpiling of inventory, or other means. (FDA, 2023h)

As of April 2024, FDA is developing guidance for manufacturers in response to the FDORA requirements.

National Strategy to Increase Resiliency

In March 2023, FDA released its Immediate National Strategy to Increase the Resiliency of the U.S. Infant Formula Market (FDA, 2023a). This strategy documented FDA’s observations during the 2022 infant formula shortage and described its immediate actions and further plans to improve the resiliency of the infant formula market. A brief description of FDA’s strategy to increase resiliency of the infant formula market can be found in Box 5-4, including the role that this current report will play in FDA’s strategy.

The Immediate National Strategy also describes FDA’s efforts to provide education and communication materials for parents, caregivers, and medical providers, and it summarizes the new authorities received in FDORA (FDA, 2023a). These actions include improving accessibility of existing FDA educational materials, coordinating with WIC to distribute consumer education materials, and enhancing partnerships with health

BOX 5-4

Components of the Food and Drug Administration’s Strategy to Increase the Resiliency of the U.S. Infant Formula Market

- Conduct surveillance food safety inspections at least annually.

- Expand and improve infant formula training for investigators.

- Continue to collaborate with major infant formula producers and retailers.

- Monitor the infant formula supply chain to assess market health to identify potential signs of challenge.

- Engage with U.S. government partners (federal agencies) to address immediate infant formula needs.

- Engage with USDA to support resiliency and reserve planning through WIC.

- Complete reviews of pending infant formula submissions from firms wanting to access the U.S. market.

- Develop policies to promote infant formula market health and diversification.

- Design and promote policies from government partners that support breastfeeding.

- Refine the Strategy to Help Prevent Cronobacter sakazakii Illnesses Associated with Consumption of Powdered Infant Formula.

- Receive new scientific data from the National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods’ charge and be ready to implement new insights to improve food safety.

- Work with the National Academies to understand their analysis on the challenges in the supply of infant formula and incorporate findings into an updated long-term national strategy.

- Analyze methods and approaches for potential international harmonization of regulatory requirements.

- Use expanded hiring authorities to support implementation of new authorities related to infant formula provided in the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022.

- Create a new Office of Critical Foods responsible for oversight of infant formula and medical foods (among other critical foods).

- Expedite review of premarket submissions for new infant formula products.

SOURCE: Text for this box is drawn from FDA, 2023a.

care providers and professionals to build a consumer education program (FDA, 2023a). In addition, the strategy describes FDA’s operational improvements, including revising its consumer complaint procedure, expanding required infant formula training for investigators, expanding the agency’s capacity to analyze infant formula samples and to facilitate infant formula reviews, and issues instructions for improved routine surveillance inspections (FDA, 2023a).

Cronobacter sakazakii Testing and Reporting

Initial CDC Response

As soon as the initial illnesses were reported, CDC collaborated with FDA on the investigation, as appropriate (CDC, 2022a; FDA, 2022b). Beginning in February 2022, FDA analyzed infant formula samples from batches that were part of the Cronobacter sakazakii investigation (CDC, 2022d; FDA, 2022b) and produced information that could be accessed directly by parents and repurposed by health care providers for dissemination to families (CDC, 2022c). CDC also provided advice for caregivers, provided information on Cronobacter sakazakii, and described the cases identified (CDC, 2022d).

FDA Call to Action to Improve Infant Formula Safety

On March 8, 2023, FDA directed a letter to individuals involved in the manufacturing and distribution of powdered infant formula (e.g., manufacturers, packers, distributors, exporters, importers, and retailers) in an effort to prevent illnesses associated with Cronobacter sakazakii; the letter provided information to assist industry in improving the microbiological safety of powdered infant formula (FDA, 2023i). Five areas were considered for improvement:

- Controlling water in dry production areas,

- Verifying the effectiveness of controls through environmental monitoring,

- Implementing appropriate corrective actions following the isolation of a pathogen from an environmental sample or a product sample,

- Implementing effective supply chain controls for biological hazards, and

- Identifying all relevant biological hazards.

The letter provides specific recommendations concerning the testing and reporting of Cronobacter sakazakii data within each of the above-noted areas. For example, as part of environmental monitoring, FDA calls for specific testing at some frequency of Cronobacter sakazakii rather than that of Enterobacteriaceae, which is not a reliable index organism (FDA, 2023j; NACMCF, 2015). FDA also makes a strong recommendation for using whole-genome sequencing, as well as the public database of genomes available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information of the NIH, to analyze and investigate any instance of isolation of Cronobacter sakazakii in the production environment or product.

The actions proposed by CDC and FDA to increase genomic testing and storage of the data in public databases is essential for facilitating outbreak investigations in the community and for guiding practices to improve the safety of infant formula in production facilities.

Addition of Cronobacter as a Nationally Notifiable Disease

On June 29, 2023, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) voted to make invasive Cronobacter sakazakii infections in infants nationally notifiable as is already the case for Salmonella, Listeria, and other pathogens (CSTE, 2023). The CDC has stated that it would support CSTE’s position and add invasive Cronobacter sakazakii infections in infants to its national list in 2024, and each state may adjust its own reporting requirements; reporting to CDC is not required (FDA, 2023k). Together with participants from state and local health departments and FDA, CDC supported a Cronobacter Implementation Workgroup led by CSTE and the Association of Public Health Laboratories. In addition to Cronobacter sakazakii becoming a nationally notifiable disease, CDC began developing an electronic case surveillance tool for Cronobacter sakazakii case reporting by states within the CDC reporting platform (NASEM, 2023b). CDC is also creating protocols for responding to Cronobacter sakazakii clusters and outbreaks (NASEM, 2023b). CDC is validating its PulseNet database and methods for outbreak detection using whole-genome sequencing for Cronobacter sakazakii species (NASEM, 2023b).

International Framework for Infant Formula

Since the 2022 infant formula shortage, Health Canada has noted that other international infant formula regulators (including the European Union, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) have embarked on regulatory modernization initiatives for foods for special dietary purposes, which, in many countries includes infant formula (Health Canada, 2023a).

CHARACTERIZING SUPPLY DURING AND AFTER THE SHORTAGE

This section describes how the infant formula supply chain was affected by the events surrounding the 2022 infant formula shortage. It includes descriptions of effects on upstream production processes—primarily infant formula manufacturing, and the downstream supply chain, including distribution, retail, and product availability in the home.

Upstream Supply Chain

Although the 2022 infant formula shortage was not caused by reductions in upstream ingredients or packaging materials, these items are equally vulnerable to supply chain challenges. In a public session, the committee heard about the challenges that infant formula manufacturers had in obtaining sunflower oil after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, as Ukraine is a major producer of this ingredient (FDA, 2023a; NASEM, 2023c). In the same session, the committee also heard about concentration and vulnerability in vitamin premix ingredient production, which was described in Chapter 4 (NASEM, 2023c).

Manufacturing of Infant Formula

Concentration

Although sales in the U.S. market are highly concentrated by brand at the national and state levels, the concentration in production is most relevant to both the likelihood of a shortage and the ability to buffer the effects of a shortage. There is concentration in recent years related to the number of companies manufacturing infant formula to the number of manufacturing facilities, and the types of products and number of lines creating each product in a facility. The shortage that occurred in 2022 resulted from the temporary closure, due to possible contamination, of one plant that produced all of the metabolic infant formula made by that manufacturer, and the company was not resilient to this closure (FDA, 2022e). In this situation, the internal concentration within a single manufacturer was a key factor in leading to the shortage.

Production

Exempt infant formula

On February 17, 2022, Abbott voluntarily recalled three of its powdered exempt infant formulas (FDA, 2022e). On February 28, 2022, Abbott voluntarily recalled an exempt infant formula for uncommon disease (PM 60/40 for infants with kidney disease) (Abbott Nutrition, 2022a). This did not include any metabolic exempt infant formula. Shortly after, Abbott closed its plant in Sturgis, Michigan. As described in Chapter 4, infants requiring these exempt infant formulas have limited choices during a shortage, as they cannot use alternative products. However, some of these items can be purchased online (albeit with incorrect labeling) (Babies Nutrition, n.d.; Vitality Medical, n.d.). During the shortage, many families also reported difficulty accessing exempt infant formulas that some speculated may have been exacerbated by consumers

purchasing these exempt formulas for infants who did not have a medical need for them (Abrams and Duggan, 2022; Marino et al., 2023; Sylvetsky et al., 2024).

The marketplace dynamics led to substantial shortages of key exempt infant formulas even though relatively small amounts of these are used in the marketplace, compared to non-exempt formulas (FDA, 2023a; Sylvetsky et al., 2023). When production was restarted at the Sturgis facility, exempt hydrolyzed amino acid–based formula and exempt metabolic formulas were among the first to be produced (Abbott Nutrition, 2022b).

Non-exempt infant formula

Prior to the closure of Abbott’s plant in Sturgis, Michigan, there were no recalls on any non-exempt infant formula. However, Abbott’s plant closure in February 2022 caused a decrease in the availability of non-exempt infant formula (Sylvetsky et al., 2024). After the recall and closure of the Abbott Sturgis facility, other U.S. infant formula manufacturers worked to increase production of infant formula to compensate for the disruption (FDA, 2023a).

To increase the volume of infant formula leaving the manufacturing facility, infant formula was packaged in larger cans (NASEM, 2024a). Abbott also increased imports of infant formula from its plant in Ireland (an FDA-registered plant). Abbott indicated in May 2022 that it was “making daily air deliveries from Ireland and this year [2022] will triple the amount of powder imported from Ireland” (Kulisch, 2022). RBMJ indicated in December 2022 that “its formula factories are operating 24/7, and that it was feeding more than 40 percent of all low-income WIC infants” (Reuters, 2022a). Coordinating this increase in production by federal officials and manufacturers was challenging (NASEM, 2024a). As mentioned in Chapter 4, caprine-based (goat’s milk) infant formula was a new type of non-exempt product that entered the market during the shortage under enforcement discretion (Jung et al., 2023a).

Downstream Supply Chain

This section of the report covers how distribution and retail portions of the supply chain functioned during the 2022 infant formula shortage.

Distribution

A lack of transparency in how distributors move infant formula through the supply chain did not trigger any major concerns before the 2022 infant formula shortage. However, during the shortage, the lack of transparency made it impossible for officials to adequately target the source of insufficient stock of infant formula reported by retailers (NASEM, 2024b). In a public session, the committee heard that, during

the shortage, manufacturers submitted relatively routine updates (i.e., data) on production, but the location of the infant formula between the manufacturer and the retailer was unknown (NASEM, 2024b).

Vendors

Retail

Anticipating shortages, in response to the Sturgis plant closure and recall initiation, in February 2022 (see Appendix C) FDA requested that the Food Industry Association (FMI) ask retailers to limit sales to no more than five cans per shopper, which was relayed to retailers immediately (NASEM, 2023d). However, it was unclear how effectively these measures were implemented by retailers across the nation (Reuters, 2022b). According to congressional testimony offered by an owner and manager of a small grocery in Georgia, his company limited the number of canisters customers could purchase at one time, as well (Gay, 2022). In spite of these measures, shortages of infant formula in the United States peaked during the summer of 2022. Out-of-stock rates, typically measured as non-availability of products on retail shelves, ranged from 18 to 70 percent (Jung et al., 2023b), with rates above 90 percent in several states including Arizona, Mississippi, California, Nevada, Tennessee, Rhode Island, Louisiana, Florida, and Washington, many of which were states that held WIC contracts with Abbott (see Figure 5-3) (USDA, 2022j). Measures of out-of-stock rates on shelves,13 however, did not account for availability of substitute products that consumers may have had access to during this period; in fact, on-shelf availability rates showed slightly better product availability (Nielsen IQ, 2022).

While multiple news organizations reported that infant formula manufacturers increased production over time, some store shelves remained minimally stocked owing to multiple causes, including potential difficulties in moving stock from one distribution center to another, as well as long-standing disparities in food access and distribution for those living in rural communities, neighborhoods without major grocery stores, and tribal communities (Bustillo, 2022; Ketels, 2022). These smaller retailers are likely not part of the data collected by third-party data collection companies such as Nielsen and Information Resources, Inc., calling attention to the scarcity of real-time data (NASEM, 2024b).

___________________

13 Note that third-party data collection companies used different metrics and methodologies for measuring shortages of infant formula, resulting in sometimes wide differences in the reported out-of-stock rates as seen in FDA’s Immediate National Strategy to Increase the Resiliency of the U.S. Infant Formula Market (FDA, 2023j).

SOURCE: USDA, 2024c.

Hospitals

During the 2022 infant formula shortage, some health care providers were concerned that their patients would be unable to access a safe supply of medically indicated infant formula after hospital discharge (NASEM, 2023d, 2024a). Anecdotally, it was reported that this may have affected hospital discharge practices, but the committee is unaware of any data collected on this practice (NASEM, 2023d). At least one large hospital reported supplying some limited quantities of infant formula to special-needs patients after discharge during the shortage (NASEM, 2023d), but in general, caregivers procured infant formula from sources outside the

hospital after discharge (NASEM, 2023d). The committee heard from a senior advisor from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that at least one hospital delayed discharge for fear that patients would not be able to obtain infant formula on their own (NASEM, 2024a). For metabolic formulas, in April 2022, FDA issued an updated advisory and worked with health care providers to ensure awareness of Abbott Nutrition’s process for releasing metabolic formulas on a case-by-case basis from the Sturgis plant (see Appendix C).

For healthy term-born infants with a brief postnatal stay, it was not clear—as reported during the committee’s information-gathering sessions (see Appendix D)—whether there were additional incremental efforts in maternity, neonatal, and pediatric wards to support breastfeeding given the infant formula shortage. However, it is noteworthy that rates of breastfeeding initiation, which generally occurs in-hospital, among both WIC-eligible participants and WIC-eligible nonparticipants increased during the shortage and fell again post-disruption, but remained higher than pre-disruption levels (Thoma et al., 2024).