Health Systems Science Education: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 3 Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating Successful Health Systems Science Training Programs

3

Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating Successful Health Systems Science Training Programs

Reamer Bushardt, professor, clinician, and administrator in academic medicine within Massachusetts General Hospital Institute of Health Professions, welcomed participants to the November 2 session. It was designed to explore how educators in different learning environments can design, implement, and evaluate health systems science (HSS) programs in health professions education and training for health promotion, disease prevention, and patient care—that is, the quintuple aim.

DESIGNING AND IMPLEMENTING HEALTH SYSTEMS SCIENCE IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

Alongside basic science and clinical science, HSS is the third pillar of medical education, echoed Jed Gonzalo, senior associate dean for medical education, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. Several approaches to integrating HSS into medical schools and residency programs exist, as do obstacles to integration. Gonzalo commented that although his specialty area was HSS in medical education, many of the core competencies and approaches for integration are also applicable to other health professions.

Graduate medical education (GME) has been aimed at the same six core competencies for over 2 decades: patient care, knowledge for practice, professionalism, interpersonal communication skills, practice-based learning/improvement, and systems-based practice. This framework is very similar to the education for other health professions, such as nursing and pharmacy. Nearly all competency frameworks for health professions education include systems-based practice and related topics, such as population

health, quality and safety, informatics and technology, leadership, and professionalism. The American Medical Association (AMA) framework presented at the beginning of the workshop (see Figure 1-2) represents each of these areas and integrates them into HSS.

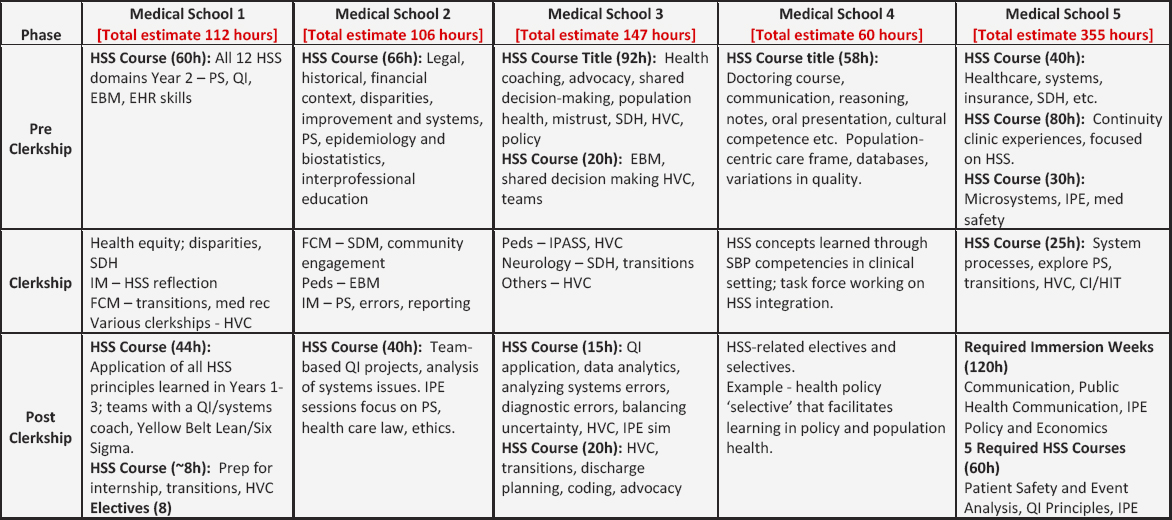

Across different medical schools, integrating HSS into the curriculum can look very different. Gonzalo and his colleagues examined five different schools and compared their HSS content in the preclerkship, clerkship, and postclerkship phases (see Figure 3-1). They found that schools varied considerably in hours required, from a low of 60 to a high of 355. Most schools have a specific course or thread in HSS in the preclerkship phase, and some schools integrate directly into their practice of medicine course. The clerkship and postclerkship phases have dedicated courses, “internship bootcamps,” and electives. For example, University of California San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine has a clinical microsystems clerkship, in which several students work with a faculty member to identify and address systems gaps in their clinics (Chang et al., 2023).

Competencies—including HSS competencies—are best learned within the clinical community of practice, said Gonzalo, with increasing calls for learners to authentically participate and contribute to care, which led to the concept of “value-added medical education.” This can be defined as “experiential roles for students in practice environments that can positively impact patient and population health outcomes, costs of care, or other processes within the health system, while also enhancing student competencies in Clinical or Health Systems Science.” The idea, said Gonzalo, is for students to gain needed competencies while also adding value through their contributions. Traditional “value-added” roles for medical students include monitoring care plans and educating and coaching patients. New roles can help students learn about systems and gain HSS competencies; these include patient navigator, quality improvement team extender, population health manager, and safety and patient care analyst. These types of roles help learners bridge HSS competencies into the clinical space, he said.

Integrating HSS into medical school education does have challenges, said Gonzalo. Studies have identified a number of these, including the following:

- Student perceptions and interest,

- Faculty knowledge or skill,

- Lack of reliable assessments of HSS competencies,

- Disagreement about physicians’ role in HSS,

- Finding space in the curriculum for new content, and

- Lack of opportunity in clinical learning environments.

SOURCE: Figure created and presented by Jed Gonzalo on November 2, 2023, at the workshop titled Health Systems Science Education.

Despite these challenges, Gonzalo said, the last 10 years have seen a lot of movement, and he is optimistic about the future of HSS in medical school education.

EVALUATING HEALTH SYSTEMS SCIENCE PROGRAMS

Following Gonzalo’s general discussion of implementing HSS in education, Abbas Hyderi from Kaiser Permanente (KP) Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine (KPSOM) talked more specifically about how it embedded HSS concepts into its medical education program. KPSOM opened in 2020; it is located in Pasadena, California and part of the KP health care system, with no affiliation with a parent university. It has 50 students per class who are supported in exploring whatever field they choose. It was founded with the principle that HSS was a neglected third pillar of medical education, and it is “structurally baked into the DNA of the school.” KPSOM has only three departments: clinical science, biomedical science, and HSS. HSS has a 4-year footprint, said Hyderi, and is integrated into various courses and experiences. It is woven throughout the curriculum, incorporating threads of advocacy and leadership, ethics, health promotion, interprofessional collaboration, and equity, inclusion, and diversity. Instead of a traditional clinical training program of “4 weeks of this or 6 weeks of that,” KPSOM has a 2-year immersion program at a community health center and longitudinal integrated clerkships. Integrating systems-based practice into the clinical space “takes some work,” said Hyderi, because it requires buy-in and cooperation from both the clinical side and the faculty. In the clinical environment, KPSOM has a physician coaching program, in which students are guided by content experts as they work on their competencies. Coaches are given training and assigned 12–14 students to follow for 4 years; students meet with coaches individually and also as a cohort. During the third and fourth years of medical school, students can specialize further in HSS, with 4 weeks of community medicine and 8 weeks of HSS curriculum.

Hyderi described a few key elements of the KPSOM educational experience in more detail. Students complete six longitudinal integrated clerkships (LICs) at one of six KP medical centers. Students focus on family and internal medicine for the first year, then rotate through other areas of medicine in the second year. They begin their LIC within the first month of medical school, with one preceptor per student per LIC. Students also participate in a required service-learning project in which they spend half a day per month at a federally qualified health center and 1 hour per month in practicum or reflective work. Students’ time is largely spent not in clinical care but in partnering with social work and public health professionals to understand and address social, economic, and environmental factors that influence health.

KPSOM has eight educational competency domains; Hyderi highlighted three that differ from standard medical school domains:

- Population and community health,

- Lifelong learning, and

- Interprofessional collaboration and teamwork.

Hyderi noted that including population and community health serves as a “driving force” for bringing HSS to light and giving it attention. Learners are assessed on each competency at three points in training, and advancement is determined by a competency committee.

KPSOM uses a dual assessment system from Day 1 through graduation, said Hyderi. On one side, students are assessed through standard course-based exams and must meet a certain level to pass a course. On the other side, they are assessed based on competencies; this approach is longitudinal and includes multiple educational program outcomes and milestones. Data points for assessment include portfolios, dashboards, milestones, and narrative comments. Objective structured clinical exams (OSCEs) are assessments based on patient encounters; KPSOM follows these encounters with opportunities to apply biomedical and/or health science. For example, a patient may not be doing well because they cannot afford their medications or had a poor transition of care. The learner needs to identify the underlying issue and articulate what they would do about it, said Hyderi. A fair amount of faculty effort is involved in these assessments, but HSS competency assessment is better served with this level of involvement. In addition to faculty assessments, students are also assessed by their partners in their community practicum projects.

As a brand new medical school, KPSOM had the opportunity to build everything from scratch, said Hyderi. The challenge—or “fun part”—was figuring out how to represent the students when they were applying for residency programs. Integrating HSS is one of the most distinctive features of KPSOM, and the school tries to be very clear about the educational outcomes that are expected by the end of the program. Every assessment is linked to an outcome, and a dashboard provides a visualization of student progress, which can be viewed in multiple ways: by individual students, across time, as a cohort, etc. Hyderi said that having good cohort-level assessment data is critical for good program evaluation. A cohort’s progress in an area can serve as feedback on the program and allow for iterative curriculum design and redesign.

Hyderi identified several challenges in the effort to integrate HSS into medical school curriculum. First, he said, it has been “messy” trying to evaluate implementation; the school is using a variety of approaches, including surveys and focus groups, to gather information. One finding has been that

how the school defines HSS is slightly different than how students understand and experience it. It will be important to dig further into this finding, he said. Another challenge is longitudinal tracking; KPSOM can evaluate learners and their development of HSS competencies over their 4 years, but once they enter residency or practice, it becomes much more difficult. Hyderi said it is working on 5- and 10-year tracking mechanisms, which will also be helpful to demonstrate the program’s effectiveness to funders.

INTERPROFESSIONAL SYSTEMS LEARNING

The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Institute of Health Professions is the only degree-granting institution within the Mass General Brigham health care system, said Kimberly Erler, Director of Tedy’s Team Center of Excellence (Tedy’s Team COE) in Stroke Recovery and Associate Professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy within the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at the MGH Institute. MGH Institute educates health professions learners in a number of disciplines, including nursing, occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech-language pathology, genetic counseling, physician assistant, as well as health professions education, healthcare administration, healthcare data analytics, and rehabilitation sciences. The core educational model of the MGH Institute is interprofessional education and practice, said Rachel Pittmann, assistant professor of communication sciences and disorders and assistant dean for interprofessional practice at MGH institute. Its Tedy’s Team Center of Excellence (COE) in Stroke Recovery (2023) serves as “fertile ground” for students to learn from, with, and about one another. This pro bono practice center fills a gap in the care for stroke survivors while simultaneously meeting students’ learning needs. It brings together learners from occupational therapy, nursing, audiology, speech language pathology, and physical therapy. Students can practice their clinical professionalism and team skills in this authentic practice environment and learn how their role on a health care team is both unique and complementary to the roles of their interprofessional colleagues. Working as a team with the client, students from different health professions learn about all aspects of stroke recovery, including nutrition, activities of daily living, and medication management.

Students at MGH Institute also have the opportunity to develop leadership skills and to learn how to be agents for change. All students, faculty, and staff are required to participate in the Power, Privilege, and Positionality course, said Pittmann; interprofessional teams work together to build foundational knowledge around topics of justice, equity, social determinants of health (SDOH), oppression, and intersectionality. Teams explore how these concepts are relevant in health professions education, health care practice, and the larger health care system. This coursework, said Pittmann,

prepares students to examine the impact of racial and social injustices in the health care system. Students are also encouraged to use this knowledge and perspective to be advocates for change at the systems level. For example, occupational therapy students traveled to Washington, DC, to advocate for expanding telehealth services and patient-centered reimbursement models.

A third component of the program, said Erler, is the emphasis on systems thinking and harnessing the patient’s voice. Students working in Tedy’s Team COE learn to build a comprehensive profile of who their patients are so they can see past the diagnosis and help the patient rebuild their identity. Although students learn clinical skills in their individual disciplines, parallel learning activities also foster systems thinking. The example she shared was how students are asked to examine a stroke survivor’s journey from the onset of the stroke through the multiple transitions in care; this gives students an opportunity to think about the challenges and areas for improvement in the system. Tedy’s Team COE also engages learners and patients in community events, such as a “stroke wellness walk” along the waterfront in Boston. During this event, student ambassadors carefully considered the barriers and facilitators to participation after stroke, for both their specific patients and stroke patients in general. These types of opportunities, said Erler, bring to life the patient- and community-centered care that is taught in the classroom.

FACULTY DEVELOPMENT

Luan Lawson, senior associate dean for medical education and student affairs at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine Dean’s Office, told workshop participants about her efforts to implement a medical school curriculum that integrated and emphasized HSS. When she and her colleagues began, they hoped to build a longitudinal curriculum and a distinction track for a cadre of students to specialize in HSS. However, the first barrier that emerged was a lack of faculty to teach these students. In addition to a lack of expertise in the area, faculty did not have the time or financial support to fully contribute. Some pushed back against the entire idea, she said, claiming that HSS should not be a competency for medical students. Lawson and her colleagues had to take a step back and build a foundation for the importance of medical school training in HSS. A group of students met with faculty to discuss the opportunities for changing institutional culture and aligning the educational model with health system priorities. Lawson and her colleagues began to design a faculty-development program but first reached out to faculty for support and buy-in. A list of desired components was developed; the program should be interprofessional, problem centered, immediately applicable, developed with the input of faculty, voluntary, and able to provide tangible products as outcomes.

An initial model for faculty development was put together, said Lawson, and it focused on both content and process. One challenge, she noted, was convincing hesitant faculty that they actually had the expertise to be teachers based on their own lived experiences. The program used educational and leadership development, and each participant conducted a longitudinal quality improvement project. They hosted sessions in which faculty, students, and residents gathered to learn together and reached out to resources from other areas, such as faculty from the business school. Getting faculty to participate in their development program required careful thinking about what people find meaningful and valuable. Initially, the School of Medicine supported participants with protected time for participation, while other health professional schools had resource constraints that did not allow them to incentivize participation and required them to think creatively. The incentives varied by profession; some colleagues were able to get formal recognition for their participation, and others were concerned with promotion and tenure guidelines. The team encouraged and supported the scholarly activity components and provided coaching in scholarship. The program had a number of unanticipated positive outcomes, said Lawson, particularly collaboration, mentoring, and relationship building across professional lines.

The Teachers of Quality Academy, as the program came to be known, resulted in developing “an entirely new set of diverse educators that really looked at things differently,” said Lawson. Faculty participants began to look at curriculum through a quality improvement lens and question existing practices. This shift in perspective changed how faculty engaged with learners and enabled new and innovative practices. It built an informal grassroots effort in interprofessional education, and educational opportunities were founded in the connections that had been made. It has expanded, shifting to a focus on clinical mentors and role modeling and putting participants into interprofessional teams to carry out their quality improvement projects. To keep the program going, Lawson said that mentoring and succession planning have been essential. As early adopters participate and gain skills, they quickly move up and into other professional opportunities, so it is critical to have a robust pipeline of new participants.

PARTNERSHIPS FOR SYSTEMS LEARNING

Teri Kennedy, a social worker by training, is the associate dean of interprofessional practice, education, policy, and research in the School of Nursing at the University of Kansas. She spoke about her work with the Student Health Outreach for Wellness (SHOW). SHOW is a student-led, faculty-mentored free clinic for adults experiencing homelessness that launched in 2013 through a unique triuniversity partnership among

Arizona State University, Northern Arizona University, and the University of Arizona. The clinic serves as a learning laboratory to train health and social care students by fostering real-world experience while preparing them for collaborative, interprofessional practice, said Kennedy. One of the first activities was completing health assessments for Crossroads, Inc., a large provider of residential substance-use disorder services. To meet new licensure and reimbursement requirements, Crossroads needed to complete health assessments within 7 days of admission. Its CEO approached the SHOW director and proposed a pilot collaboration; the program Meeting at the Crossroads was born.

Kennedy described the details of this program by walking through the four competencies in the outer ring of the AMA HSS framework (see Figure 1-2): teaming; change agency, management, and advocacy; ethics and legal; and leadership.

Teaming

The SHOW team included students and faculty preceptors from multiple undergraduate and graduate health and social care professional programs as well as programs outside of the health sector. The fields included nursing, social work, occupational therapy, physical therapy, nutrition, pharmacy, physician assistants, medicine, global health, as well as business, journalism, law, and computer science (Harrell and Dibaise, 2017). What was really unique, said Kennedy, was integrating undergraduate students from a variety of academic programs, such as finance or computer science. Meeting at the Crossroads used a similar interprofessional approach but added substance-use counselors and the quality director of Crossroads. SHOW students and Crossroads current and emerging practitioners learned core competencies together in an interprofessional clinical environment, and faculty also learned new roles and responsibilities alongside students.

Change Agency, Management, and Advocacy

Students involved in SHOW and Meeting at the Crossroads had opportunities to learn about health equity and social justice, said Kennedy, particularly diversity, inclusion, equity, oppression, bias, and culture and how to assess individual SDOH. Through their own discipline-specific lens, students directly interacted with high-risk populations and navigated complex presentations of SDOH. Teams were exposed to a variety of assessments used by different professions in treating individuals with substance-use disorders. When the Crossroads partnership formed, said Kennedy, the opioid crisis in both Arizona and the country was putting a spotlight on the importance of treatment. The partnership was positioned to respond to the state’s

top public health priority and address the complex care needs of Crossroads clients. Students were also able to participate in quality assurance activities, such as looking at workflows or gaps in care to identify areas for improvement. Some Crossroads teams included a component in which students learned about clinic policies and relevant state and federal policies.

Ethics and Legal

Students learned about their shared values and codes of ethics through their work at SHOW and explored ethical dilemmas in practice. This was an area for important discussion and conversation among students and faculty. In addition, they learned about state and federal laws for service providers, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, state licensure requirements for clinics, and requirements under Medicaid and the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System.

Leadership

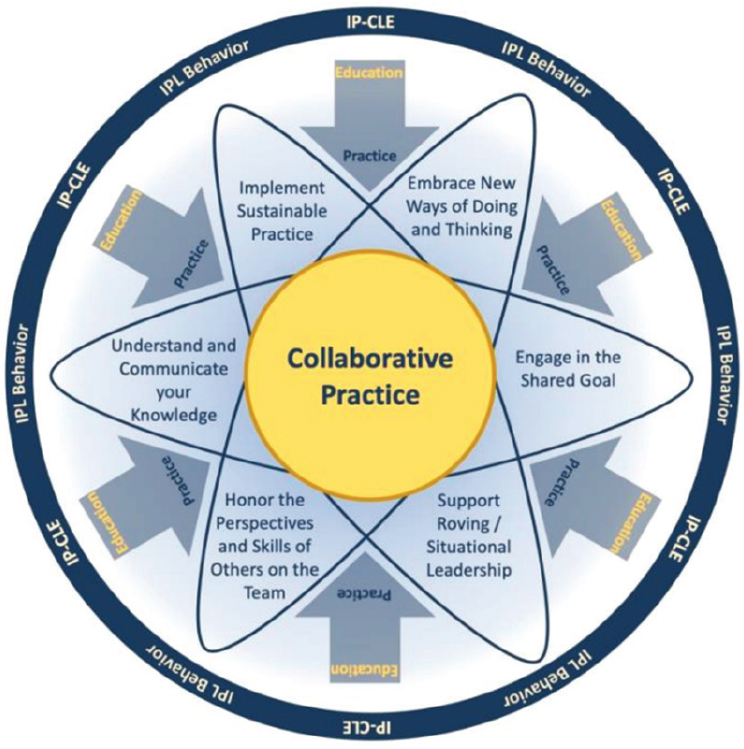

The final component of the HSS outer ring is leadership, said Kennedy. Students developed different kinds of leadership skills through a wide variety of experiences. They learned collaborative leadership through serving on interprofessional teams that focused on different areas, such as clinical practice, scheduling and workflow, policy, outreach, and fund development. In collaboration with a nursing colleague, Heidi Sanborn, Kennedy participated in a qualitative exploratory study to examine leadership behaviors evidenced by student leaders and to identify the ingredients of the “secret sauce” they observed happening in the clinic. Student participants described novel concepts in leadership, including a flattened hierarchy with roving leadership; this approach deviated from the traditional hierarchy of team leadership, said Kennedy. Sanborn and Kennedy identified six core behaviors of collaborative practice among the students in the program (see Figure 3-2):

- embrace new ways of doing and thinking;

- engage in a shared goal;

- support roving, situational leadership;

- honor the perspectives and skills of others on the team;

- understand and communicate your knowledge; and

- implement practices that are sustainable.

Both SHOW and Meeting at the Crossroads focused on learning in practice, said Kennedy. Learning opportunities at SHOW included a weekly weekend clinic, an annual health fair, street medicine to provide care to

SOURCES: Presented by Teri Kennedy on November 2, 2023, at the workshop titled Health Systems Science Education. Figure created by Heidi Sanborn for Sanborn and Kennedy. 2021. “Fostering Collaborative Practice Through Interprofessional Leadership Behaviors.” Nexxus Summit.

unsheltered individuals, and hotspotting to target and improve care for super-users. Students involved in Meeting at the Crossroads engaged in direct patient care, weekly huddles with faculty preceptors and practitioners, preceptor/student treatment projects, and developed health promotion services. Based on their work, students prepared posters and presentations that they presented on campus and at conferences.

An assessment of SHOW and Meeting at the Crossroads found that students broadened their knowledge of how physical, behavioral, and social

dimensions and SDOH contribute to problems. Engaging with the facility staff who worked with residents, students were able to learn how they were progressing from week to week in treatment. Students and faculty preceptors gained an understanding of each discipline’s unique and overlapping roles in treating unhoused adults and adults living with substance-use disorders, said Kennedy. Qualitatively, students reported increased confidence in collaborating with other members of the interprofessional team, greater understanding of whole-person care, peer-guided care, substance-use treatment systems, and a commitment to serving people living with substance-use disorders. Kennedy reported on learners’ strong commitment, demonstrated when five students who participated in the pilot program accepted postgraduate positions working with adults with substance-use disorders.

Kennedy quoted Quatman-Yates, that once you see the world through a systems lens, “it’s really hard to turn it off.” By educating students through a systems lens and giving them opportunities to engage with communities and systems, HSS will become “the air they breathe over time,” said Kennedy. She closed with a few key lessons about successful implementation of an HSS-focused program for learners in the health professions. First, start with people, families, and communities, and address their critical needs. Second, relationships matter, and it is worth taking the time and investment to build them. Third, academic–community partnerships can and should be created using a systems lens. Fourth, partners should have an agreement in place that clarifies the roles and responsibilities of each party. Finally, educators need to ensure that curriculum doesn’t “get in the way of student learning.” Sometimes, it needs to evolve and grow to the meet the needs of the future workforce.

DISCUSSION

Creating a Guiding Coalition

In the book Health System Science Education: Development and Implementation (Maben-Feaster et al., 2022), three things are required before implementing HSS education, said Bushardt: “look before you leap,” create a sense of urgency, and create a guiding coalition. Bushardt asked Gonzalo to elaborate on the third item and to explain who should be in this coalition and how they can be engaged. Gonzalo responded that in his conversations over the last 10 years with medical schools that are interested in integrating HSS, he always begins by asking who is “leading the charge.” He said that he has learned that if top leaders—such as deans—are not on board, the team will struggle to implement HSS. Challenges always arise when making changes, and some pushback is inevitable from students, faculty, and others. To make a paradigm shift in education, leadership

needs to view it as aligned with their mission and vision. Gonzalo said that this process is similar to the diffusion of innovation framework. The early phases of any change will have laggards who are not on board; with HSS, they may resist because they do not believe that it is part of the physician’s role. In Gonzalo’s experience, HSS implementation is 80 percent change management—getting people to agree and adapt—and 20 percent the technical piece of developing curricula, learning objectives, and assessments.

Preparing Faculty for Change

A participant asked Hyderi and Gonzalo about how they have worked with faculty to make the changes necessary to implement HSS. Hyderi responded that one advantage to being a new school is that their faculty were “very green”; many had never taught in a health professions program, so KPSOM was able to emphasize faculty development and teach the desired roles and responsibilities. Gonzalo said that getting faculty is a struggle and a “long game.” He and his colleagues decided to focus efforts on two groups: educators who are directly interacting with HSS learners and leaders who can enculturate HSS within the school. Although this leaves a big gap in the short term, getting enthusiastic buy-in from all faculty requires more bandwidth and resources than are available. Bushardt added that “it’s okay for students and faculty to learn together.” During the pandemic, students and faculty were forced to rapidly change the way things were done and learn together about how to move forward. A similar approach may be appropriate or necessary when figuring out how to fit HSS into health professions curriculum.

Patients as Educators

Given that Tedy’s Center is both a provider of services for stroke survivors and a training ground for health professionals, Bushardt asked Erler and Pittmann to comment on whether and how patients and families at the center are prepared for their role. Erler responded that patients are on a spectrum, with some viewing themselves as recipients of care and some as educators for student trainees. Patients’ perspectives vary in part based on how they came to the center and how long they have been coming. Patients can attend for as long as they wish; some continue to come to receive services, whereas others enjoy the role of educator of the future workforce.

Closing Remarks

Gonzalo offered his synthesizing thoughts on the presentations and discussions. One of the major takeaways, he said, was the diversity of

approaches to systems-based practice and HSS across and within health professions education. This is a reminder that no single approach for integrating HSS exists and that an effort need not be perfect before it is rolled out. “Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good,” said Gonzalo. Educators and leaders can begin looking into their practice to see where learners could get involved and potentially add value while learning about HSS and developing needed competencies. Systems thinking has been an enigma in medical education for decades, he said, but people are beginning to talk about it. Building programs around HSS will require dealing with budget challenges, getting leaders on board, and demonstrating and using the skills that should be conveyed to learners—interprofessional collaboration, systems thinking, and humility. Gonzalo emphasized that HSS is not just an education framework; it also applies to academic health systems and clinical operations. It could be viewed as a “unifying linchpin” across the tripartite missions of academic health systems; its concepts overlap in the clinical and education spaces and can bridge the gap between the two.