Health Systems Science Education: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 2 The Value of Health Systems Science Across Professions

2

The Value of Health Systems Science Across Professions

The second session was held on November 1 and explored examples of health systems science (HSS) within and across professions as a demonstration of its value in health professions education and training for health promotion, disease prevention, and patient care (i.e., the quintuple aim1). Lomis moderated the session, which consisted of presentations from a variety of disciplines and areas.

MEDICAL SCHOOL

Natasha Sood, a clinical fellow in anesthesia at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, told workshop participants about her experiences in an intensive, 4-year HSS curriculum at Penn State College of Medicine. HSS has been “absolutely foundational” to understanding and navigating the complex health system, said Sood, and led her to advocate for change to improve patient care. Providing efficient and effective care to patients and families is the “reason we’re here,” said Sood. It requires coordination and collaboration among a diverse health care team that includes professionals such as pharmacists, nurses, social workers, physicians, and respiratory, physical, and occupational therapists. In addition, working with professionals in administration, engineering and facilities, and operations is critical for ensuring that the necessary infrastructure and resources are in place.

___________________

1 The quintuple aim builds on the triple aim to also recognize provider burnout and health equity for all (Nundy et al., 2022).

One of Sood’s first HSS experiences in medical school was working on a set of standardized patient cases in the simulation lab. The team, which consisted of students in medicine, nursing, pharmacy, social work, and physical/occupational therapy, was assessed for their clinical knowledge, patient care, and interprofessional communication and collaboration. This experience taught her a lot about the unique role and unique training of her health care colleagues and helped her understand the dynamics of the team and how to work together to optimize care. Building on this experience, Sood remarked that one of her favorite and most valuable HSS experiences in medical school was working with a professional patient navigator who met one on one with patients in the community to address barriers to care. This was a pivotal position, she said, because he was based in the community but also coordinated care with inpatient social work and clinical care teams. With the patient navigator, Sood followed one patient for a full year as he tried to qualify for bariatric surgery. She helped him navigate disability insurance, obtain a home hospital bed, and develop a balanced meal plan. She listened as he described his significant childhood trauma that led him to where he was. Sood said that this experience made it abundantly clear how social, psychological, and environmental factors impact health and serve as significant barriers to getting needed care. The experience demonstrated how all the components in American Medical Association’s (AMA’s) framework (see Figure 1-2) interact with one another and create the system of care for the patient, Sood noted.

In Sood’s second year of medical school, the pandemic and 2021 Pacific Northwest heat wave served as further examples of HSS in practice. Sood noted that she has a particular interest in how climate change and natural and human-made disasters impact health system functioning and how these systems can be made more resilient. The health systems were overwhelmed with patients, had dwindling supplies and lack of staff, and were navigating uncharted territory. Every sector was strained, said Sood; both systems and individuals in the systems were taxed to the point of collapse which highlighted the vulnerabilities of our systems. It is critical, remarked Sood, that more resilient systems be developed before the next disaster strikes. Recognizing the value of the broader HSS lens in responding to disaster situations, Sood worked with her mentor to map out how to incorporate climate and sustainability concepts into the HSS curriculum in her medical school. The six core domains of the HSS curriculum are structure and process; policy and economics; informatics and technology; population, public, and social determinants of health (SDOH); value in health care; and health system improvement. Within each of these domains, Sood and her mentor identified ways to incorporate climate change and sustainability concepts. More specifically, health care structure and process offers an opportunity to introduce learners to concepts of energy efficiency and waste and think

about how patient experiences could be improved while reducing pollution and costs.

Sood concluded that health professions learners need opportunities to understand HSS by seeing how different sectors can collaborate in addressing external factors—whether climate change or racial injustice—that impact health systems and the experiences of each individual within them. Understanding the interactions between each part of the system and the influence of external factors, said Sood, is critical for creating a more sustainable and just system for patients and families.

DIAGNOSTIC SYSTEMS

Diagnosis is the entry point for most people into the health care system, said Kristen Miller, senior scientific director at the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare within MedStar Health Research Institute. Patients have powerful stories about their experience of struggling to find the correct diagnosis and medication. Miller told participants about her work on the misdiagnosis of cardiovascular disease in women as an example of HSS. Although women suffer from it at high rates, its presentation in women, according to Vogel et al. (2021), is “understudied, under-recognized, underdiagnosed, undertreated, and women are underrepresented in clinical trials.” There is a confluence of events that contributes to this misdiagnosis, said Miller. It presents differently in women than in men, and both the public and providers are sometimes unaware of the symptoms to look for in women. This has multiple consequences, including women failing to seek care and providers taking symptoms less seriously than they should; for example, ambulances are less likely to use sirens and lights when a woman is experiencing chest pain versus a man. Studies that have generated the majority of evidence used for clinical guidelines were focused on “older white males,” so the risk calculators and treatment guidelines may be inappropriate for other populations. The multiple contributing factors to misdiagnosis of cardiovascular disease in women presents a challenge because of the issues at multiple points in the system, which, said Miller, can also be seen as a great opportunity for addressing cardiovascular disease in women using a HSS lens.

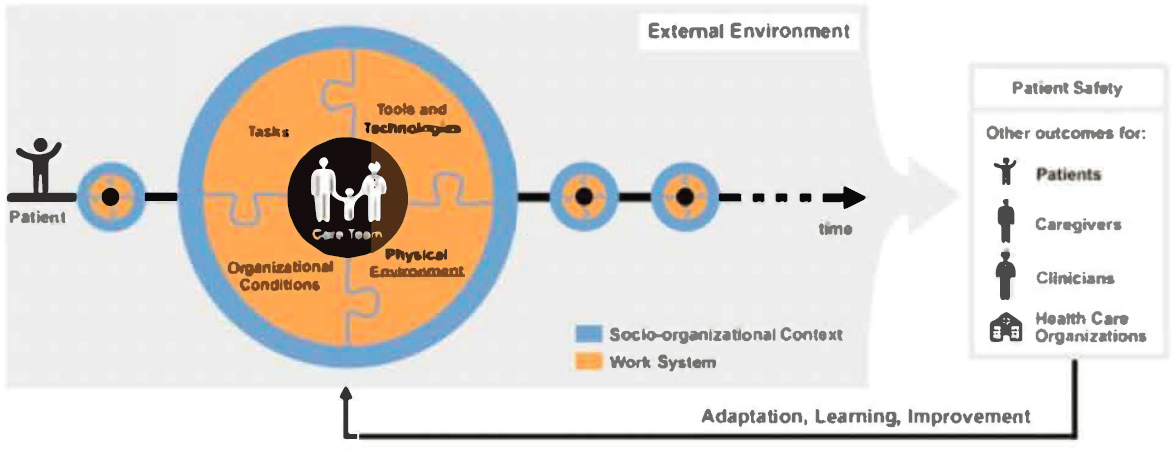

Miller and her colleagues used a transdisciplinary approach to look at the problem from multiple perspectives; the team included architects, clinicians, human factors professionals, engineers, and others. They examined the literature, conducted focus groups, observed patient interactions, looked at patient charts, and interviewed stakeholders. In addition, they used a Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model (Carayon et al., 2006) to look at how the external environment, socio-organizational context, and work system contributed to misdiagnosis (see Figure 2-1). The

SOURCES: Presented by Kristen Miller on November 1, 2023, at the workshop titled Health Systems Science Education (Carayon et al, 2020). CC 4.0.

team explored virtually every aspect of the system for potential impacts on misdiagnoses, which included the built environment, where the team observed that conversations could be heard between patient exam rooms. This led them to ask, “Does this mean that a patient might be less likely to share her symptoms when she knows she could be overheard?” and “Could windows that open onto the parking lot make a patient feel uncomfortable about undressing for the exam?”

The team’s observations and research yielded interesting findings, said Miller. About a quarter of patients reported a “diagnostic breakdown” in accuracy, timeliness, or communication. To illustrate, Miller described a telephone appointment for cardiovascular symptoms, making it impossible for the clinician to evaluate vital signs or heart function. Patient- and provider-facing guidelines are not actionable, said Miller, with a need for new tools to improve diagnosis and to empower patients as their own advocates; however, the most interesting finding was that communication is key. Miller described views of some team members who thought the built environment would be one of the main barriers, but instead, nearly every patient identified “listening” as a main priority, and some reported feeling like no one was listening to them.

Based on these findings, the team identified several interventions that impact different areas of the system. First, improved patient-facing materials can educate and empower patients. Miller noted how materials that include information about what heart attacks look like in women can be helpful for not just the one who receives them but also friends and family in their circle. Additionally, agenda-setting tools can be developed or revised to help patients go into appointments with organized and prioritized thoughts and questions. On the provider side, said Miller, there is a need for improved training, in particular, training that allows providers to watch themselves interact with patients to identify areas for improvement. Providers would also benefit from optimized clinical decision support tools to accurately calculate patient risk.

Last, the team identified an intervention in the built environment. Knowing that the layout and design of exam rooms can have an impact on a patient’s comfort and ability to open up to the provider, the team worked on changes to the physical environment that included a mobile adjustable laptop table to facilitate interactions. Cardiovascular disease is misdiagnosed and undertreated in women, Miller stated, and it is a complex problem requiring complex solutions. Using the HSS lens can make it possible to see how individual parts of the system and their interactions are impacting patient outcomes. This allows teams to identify key areas for interventions. Miller also noted that improving diagnosis in women will require a significant re-envisioning of the diagnostic process and the diagnostic team, along with a widespread commitment to change—all part of the HSS process.

CLINICIAN WELL-BEING

The characteristics of a good work environment transcend sectors. Many definitions exist, said Matthew McHugh, independence chair for nursing education and the director of the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research (CHOPR) at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, but in general a good workplace:

- values employees,

- has effective leadership that supports employees,

- empowers employees to participate and have a voice in decision making,

- has opportunities for professional development and advancement,

- facilitates good relationships among colleagues,

- has adequate staffing and resources, and

- uses technology and information systems designed with the user in mind.

Whether in health care or other sectors, a positive work environment makes a difference to employee recruitment and retention, said McHugh. Many interventions tend to focus on one category of employees (e.g., nurses), but McHugh and his colleagues were interested in taking a more systems approach by identifying common features across workplaces and professions that were associated with individual outcomes, such as burnout or job satisfaction. Comparing two prominent studies, one on nurses and one on physicians, McHugh found very similar concepts. Both stated that burnout was associated with the work environment and pointed to similar characteristics of poor environments: inadequate staffing and high workloads, inefficient operational processes, bureaucratic red tape, lack of input or autonomy, and a culture that does not support or value employees. Work environment varies significantly among different hospitals, said McHugh, as does the percent of clinicians suffering from burnout. These characteristics have an impact on clinicians and others working in the hospital and patient care.

In the nursing world, hospitals that demonstrate the characteristics of a good workplace are recognized as Magnet hospitals by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). This is a voluntary program that requires hospitals to undergo a process to improve and sustain a good work environment over decades, said McHugh. Magnet hospitals have been shown to have better clinician, patient, and financial outcomes, which are largely a function of the better work environments (Sermeus et al., 2022). Using the conceptual principles behind the Magnet program, McHugh and his colleagues wanted to test whether it was feasible and sustainable to redesign hospital work environments and whether that could result in better

outcomes for clinicians and patients. Europe had very few Magnet hospitals but many that were interested in participating in the process; 65 were chosen across six European countries and paired with a U.S. Magnet hospital “twin.” The different health care financing systems, political environments, infrastructure, and provider training in these six countries presented an opportunity to test whether the Magnet principles are universal and can be applied across contexts, said McHugh. The European hospitals worked with their U.S. counterparts to implement the Magnet principles that are associated with clinician well-being and better patient outcomes. Monthly learning collaboratives and semiannual in-person visits allowed participants to share best practices, and multiple sites in each country created a “critical mass” and increased the likelihood of sustaining the changes. The study is still in progress, but a rigorous evaluation is planned, said McHugh.

As part of this study, a companion survey of the 68 U.S. hospitals was conducted to gather information about nurse and physician well-being challenges. It found that about a quarter of nurses and physicians reported high burnout and job dissatisfaction, with slightly higher percentages saying that they planned to leave their job. Challenges with work–life balance were higher among physicians (56 percent) than nurses (39 percent), but poor overall health was higher among nurses (28 percent) than physicians (17 percent). The survey also asked nurses, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants (PAs) about “system breakdowns,” or areas where clinicians felt a disconnect with administration. Around a quarter to a third of respondents said that mistakes were held against them, they did not feel free to question authority, and the administration did not listen to employees. It is a big patient safety concern, said McHugh, when a sizable number of clinicians in the best hospitals in the country feel this way. Literature on burnout often includes potential interventions for improving the work environment. McHugh and his colleagues asked survey respondents to rank the most and least important interventions; all four groups agreed that the most important are the following:

- Improving staffing;

- Reducing documentation, bureaucracy, and red tape;

- Allowing for more time with patients;

- Uninterrupted breaks; and

- Improved work–life balance.

The least important were the following:

- Wellness champions or committees,

- Time and space for meditation and reflection, and

- Resilience training.

McHugh noted that the least important interventions are commonly implemented, whereas the most important are often ignored. In qualitative interviews, clinicians said that unwanted interventions highlight the disconnect with leadership and lack of focus on what matters to them.

McHugh shared a few HSS takeaways from his study on workplace environments and clinician well-being. First, interdisciplinary initiatives can collaboratively address core health system failures; frontline workers, regardless of profession, report very similar experiences and needs. Second, there is evidence about what works, with many examples to draw on. Although different environments may require different interventions, the principles of positive workplaces have strong theoretical underpinnings. Third, looking at different experiences in different organizations is an opportunity to advance knowledge in this area and share best practices. Finally, said McHugh, clinician learners can and should be engaged in working together toward systems-level change activities.

Jennifer Graebe, director of the Nursing Continuing Professional Development and Joint Accreditation Program at ANCC, worked with McHugh in exploring clinician well-being. She expressed a desire to have “humanness” at the center of all systems work: “Although we have patients and community at the centers of our model, many times, the humanness of the work and how it impacts the human being or human beings is not necessarily thought about as the core,” said Graebe. For example, a decision that is good for patients might lead to time pressures on providers that could adversely affect the stress level of health care workers providing the care. When we consider health professions education, said Graebe, we need to be mindful of how to center HSS so engagement with people and humanness are at the core. Particularly as technology and the use of artificial intelligence advance, connecting with the human condition will become increasingly important. Educators and facilitators of learning are tasked with helping learners find joy and purpose in their work, to create positive, healthy environments that foster well-being and promote resilience, said Graebe.

People often think of human needs based on Maslow’s hierarchy, she added, which might view employers as responsible for helping people meet their needs, from physiological needs to self-actualization. However, Graebe said that Maslow’s hierarchy was based on observations of the Blackfoot nation, which was focused more on cooperation and restorative justice rather than meeting individual needs (Bear et al., 2022). They found joy and purpose in giving away their wealth or giving food to those who needed it. Graebe said that looking at Maslow’s hierarchy in this way makes her think about her role as a nurse and how she can give away her talents and abilities rather than holding onto them in a quest for self-actualization. The challenge, she said, is for health care providers and facilitators of learning to demonstrate the emotional intelligence and human skills that are necessary

for a health system to center on humanness. Furthermore, fostering and encouraging interprofessional collaborative practice is key to HSS; working with others to improve patient outcomes helps reduce stress, improve satisfaction, and foster relationships. People in the system—from patients to providers to learners—are human, said Graebe, so keeping humanness at the core of HSS can potentially improve the health system for everyone involved.

COLLABORATION FOR BEHAVIORAL HEALTH

Collaborating across disciplines is the “life force” of behavioral health, said Teneisha Kennard, executive director of Behavioral Health–Ambulatory Services with the Department of Behavioral Health at JPS Health Network at Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium (TCMHCC) that backs the Texas Child Health Access Through Telemedicine (TCHATT) program. Kennard offered a community-based HSS example that included local government, a major health system and university, and K–12 school districts. The stakeholders were brought together through TCMHCC, which was created by the legislature in 2019 to improve mental health care and systems of care for children and adolescents. The projects under TCMHCC represent a coordinated effort to leverage the expertise of mental health professionals across the state to meet the needs of children and adolescents with mental health concerns. This is necessary, said Kennard, due to a demand for services that exceeds the number of professionals qualified and available. The effort has brought together mental health professionals and prescribers to geographically cover the state with telehealth mental health access. TCHATT provides and coordinates telehealth services for children who need it.

Funding for TCHATT is provided by TCMHCC and the Texas Higher Education Coordination Board and distributed among 12 hubs, each of which is a partnership between a health organization and an academic institution. Kennard’s hub includes the JPS Health Network and University of North Texas Health Science Center and is responsible for nine counties, which are diverse and include both rural and urban areas. Kennard and her colleagues are responsible for connecting with as many school districts as possible in these counties and working with them on providing care. She noted that one of the best parts of how the program is funded is that it is allowed to use funds to purchase iPads or supply hotspots to help schools and students connect. The areas covered by the 12 hubs vary in their needs; some larger districts already have behavioral health resources, so the TCHATT partners supplement and refer to these.

Kennard’s hub is partnered with about 40 school districts and serves more than 300,000 students. School staff have been trained and can use

a statewide referral system to connect a student with TCHATT. Most students access care during the day, in a space provided by the school, and parents are added to the session when necessary. The “no-show” rate for therapy and medication appointments is only about 10 percent. The intent, said Kennard, was to relieve the family of barriers to care such as transportation or time. The project offers students a complete and safe discharge plan, meaning that a student who needs more advanced care will get support until they can access a new provider.

When TCHATT began, said Kennard, they expected to see children with anxiety, depression, and issues with self-esteem. They quickly found that many students had significant behavioral health care needs, and many symptoms were connected to SDOH. Kennard’s team added a case management arm, and it has been very helpful to be able to connect students with community resources for food, housing, and other needs. Kennard described how each step of the process works. It begins with school district and community outreach, with teams going out to physically meet with community partners. This is where relationship building starts, with a lot of mutual learning on both sides. After much discussion and coordination, legal contracts are signed, and Kennard and her colleagues begin training and building relationships with the frontline staff who will be making referrals. She said that, ideally, providing care is seen as a collaboration between school staff and TCHATT. Once referrals begin, services can be provided. Ongoing refreshers for staff ensure that everyone knows how to connect students to services. The final step is reporting to the various agencies, from government funders to the service providers.

Providing service through TCHATT, said Kennard, requires a HSS approach that is based on collaboration and integration of multiple systems, organizations, and individuals, including the state legislature, the University of Texas system, service providers, independent school districts, local governments, and parents and students. The team that coordinates and provides services is multidisciplinary and includes administrators, medication providers, social workers, counselors, and support staff. This team works together daily to ensure that students have access to quality care. In addition, said Kennard, learners from within various systems have been involved through fellowships, residencies, and internships. Learners get the opportunity to observe the administration of this type of program, work across disciplines, and see the importance of building relationships.

DISCUSSION

Medical Education

A participant, Peter Cahn, Massachusetts General Hospital Institute of Health Professions, said that he read an article calling HSS courses the “broccoli” of undergraduate medical education; that is, students did not enjoy these classes (Gonzalo and Ogrinc, 2019). He asked Sood if she saw this with her own classmates and how this initial disinterest could be overcome. She responded that medical school can be “very overwhelming,” particularly at the beginning, and that students can be laser focused on the clinical side. As the HSS programming continued through the years of medical school, her fellow students began to appreciate it more, especially once they had done the majority of work needed to understand clinical medicine. Student interest in HSS is on a spectrum, she said, and different students are ready for it at different times. Lomis said she also had seen this spectrum of interest in her work at various medical schools, and the AMA has tried to convey the message to students that HSS is a critical third pillar of medical training. No matter how well trained an individual is in basic science and clinical medicine, she said, they will not be able to help patients navigate the system and obtain optimal outcomes without a firm grounding in HSS.

Patient Perspective

When we define a health system, it is usually from the perspective of clinicians or other health care professionals, said a participant. She asked for panelists to consider how the system might look different if it were defined by patients. Graebe responded that patients often have different views and needs than those in the health care system and that putting patients at the center requires a shift in perspective. She gave an example from her work with survivors of violent sexual crime. Every clinical practice guideline, procedure, or policy was based on what they had learned from survivors and designed to allow them to engage in the services or pathways that they chose. At the foundation, the patients had ultimate control and decision making for their care. When Graebe began working at the emergency room in Washington, DC, she encouraged nurses to shift their perspective from patients “refusing” certain care to “choosing” the care they wanted. Kennard added her perspective based on her behavioral health work in the field. Some clinicians think that their patients can improve because they are receiving therapy and medication. However, the patient sometimes has numerous unaddressed social needs; they might say, “If you really want to help me, then help me find a resource to keep the lights on and help me feed my children.” The care team needs to consider patient needs within

the larger context of the health system if they truly want to make a difference, she said.

Reinforcing Systems Thinking

Ratwani said that McHugh identified several interventions that clinicians believed would help with well-being, such as adding staff and reducing documentation. When organizational leaders see this list of interventions, they often think linearly and want to know the “one thing they can do” to make a difference. Ratwani asked McHugh and other panelists for their thoughts on how leaders can be encouraged to think with a systems lens and to see that a multitude of approaches is often necessary. McHugh responded that one way to combat linear thinking and shift to a systems lens is to emphasize the efficiency of implementing multiple interventions at once. For example, simply adding more nursing staff to an already-dysfunctional system is unlikely to be effective in improving clinician well-being, patient outcomes, or cost. Instead, focusing resources on a few areas that improve the work environment for everyone can make targeted interventions even more effective.