Modernizing Probable Maximum Precipitation Estimation (2024)

Chapter: 5 Recommended Approach

5

Recommended Approach

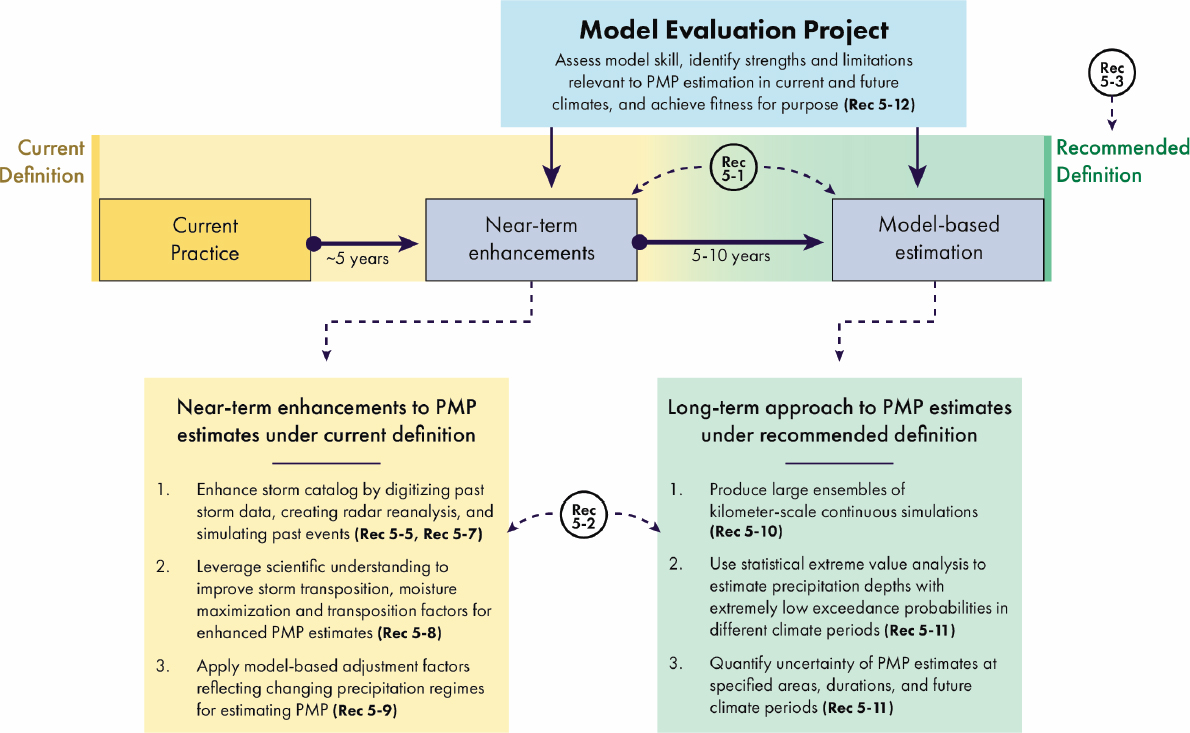

With the phased approach for modernizing PMP developed below, an initial phase of near-term enhancements to current PMP methods is followed by model-based methods for estimating precipitation depths with extremely low annual exceedance probability (AEP). The recommended approach is grounded in a broad vision to guide research and development:

Vision: Model-based probabilistic estimates of extremely low exceedance probability precipitation depths under current and future climates will be attainable at space and time scales relevant for design and safety analysis of critical infrastructure within the next decade.

Achieving this vision will require scientific and modeling advances that should engage researchers across a broad array of disciplines. These advances will contribute not only to traditional PMP goals, but also more broadly to the societal challenges linked to the changes in extreme precipitation in a warming climate.

OVERVIEW OF A PHASED APPROACH

Near-term enhancements to PMP estimation will be based on improved data, expanded use of modeling, and effective use of scientific understanding in implementation of PMP procedures (Figure 5-1). Development of radar-rainfall datasets will provide improved data for PMP estimation, especially for the sub-daily, small-area context. Observations of precipitation in mountainous terrain can be flawed, owing to insufficient density of gauges and problems with radar beam blockage (e.g., Daly et al., 1994; Maddox et al., 2002). Reconstructions of storms producing PMP-magnitude rainfall through numerical models (see Chapter 3 on Numerical Modeling and Computing) can enhance storm catalogs and inform implementation of storm transposition and maximization procedures, especially in mountainous terrain. Greater scientific understanding

will also guide implementation of PMP procedures, including the subjective decisions that are used for storm transposition. Approaches to addressing the effects of climate change can be based on temperature scaling relationships, with Clausius-Clapeyron (C-C) scaling providing the simplest method for computing climate adjustment factors until sufficiently credible model-based scaling is available.

Model-based simulations of precipitation over the United States will form the foundation for long-term modernized PMP estimation, including statistical characterization of uncertainty and incorporation of climate change effects on rainfall extremes (Figure 5-1). Large ensemble long simulations, produced by running multiple simulations with slightly different initial conditions, will provide the inputs for quantile-based statistical estimation of PMP over the watersheds of the United States based on precipitation depths associated with a pre-specified extremely low AEP. Estimates of PMP and their uncertainty will be obtained using extreme value methods. Decision makers will specify AEPs that define quantile-based PMP; PMP estimates derived from near-term enhancements will inform selection of probabilities for the long-term quantile-based PMP estimation. Model-based PMP estimation provides a natural framework for incorporating the impact of climate change, as detailed below.

The Model Evaluation Project (MEP) is a critical step in transitioning from near-term enhancements of PMP estimation to implementation of model-based PMP estimation (Figure 5-1). The advances in modeling capabilities necessary for PMP estimation will be developed and demonstrated, including approaches to incorporating the effects of climate change. At its core, the MEP will aim to determine when model-based approaches provide a suitable foundation for PMP estimation, as agreed upon by the broader community.

Recommendation 5-1: NOAA should pursue a phased approach to modernizing PMP estimation, with the near-term approach building on enhancements to conventional PMP procedures and leading to a long-term model-based framework that can provide uncertainty characterization of PMP estimates, fully incorporating the effects of climate change.

CORE PRINCIPLES

Conclusion 5-1: Four core principles should guide the development and use of modernized PMP estimates: transparency, objectivity, accessibility, and reproducibility.

Transparency plays a pivotal role in building trust among practitioners, regulators, researchers, and the public. The concept should cover data and assumptions used to estimate PMP, PMP products, computer codes, and other ancillary information used in PMP estimation. It should also apply to timelines and schedules related to production milestones and opportunities for public review and comment. Transparency forms the groundwork for independent assessment of PMP products and facilitates evidence-based policymaking.

In pursuing objectivity, the aim is to minimize the reliance on subjective judgments. As detailed in Chapter 4, estimation of PMP using current PMP methods involves multiple subjective decisions by practitioners. Advances in data, tools, and scientific understanding of extreme rainfall can enable practitioners to more objectively implement PMP estimation based on near-term enhancements (as detailed below), provide guidelines to constrain and channel subjectivity where it is required, and document the subjective decisions that underlie PMP estimates. The transition to model-based methods will greatly reduce the need for subjective decisions in PMP estimation.

Accessibility of data and approaches should also be emphasized throughout the entire process of PMP estimation. Priority should be given to publicly accessible input data, analytical methodology, and computer codes. PMP products should be regarded as public goods within the public domain and be made available to the general public with minimum restrictions. In essence, adherence to the FAIR principles (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) is vital for improved data management and stewardship.

In terms of reproducibility, the expectation is that PMP products should be broadly reproducible using the same data and methods. For near-term enhancements to PMP estimation, differences in estimates can result from subjective decisions made by different practitioners, but key decisions in PMP estimation should be documented such that differences in PMP estimates can be readily assessed by PMP users. Model-based methods for PMP estimation will facilitate reproducibility of PMP estimates. Reproducibility is closely linked to the preceding core standards, as transparency, objectivity, and accessibility are essential for ensuring the reproducibility of PMP products.

In addition to the study principles described above, the committee advocates for sustained collaboration between the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and stakeholder groups throughout the process of modernizing PMP estimation. Collaboration efforts should focus on developing long-term relationships between NOAA and end-users, establishing two-way communication pathways between groups and emphasizing the creation of usable science and products (Dilling and Lemos, 2011; Lemos and Morehouse, 2005; Meadow et al., 2015). Although collaboration among interested parties will likely be beneficial throughout the process, collaboration will be essential for certain aspects of the process, as described in more detail below.

Recommendation 5-2: NOAA should deliberately engage the scientific and practitioner communities to enhance understanding of the scientific process, clarify methodological considerations, increase awareness of practitioner needs, and collaboratively shape resulting products in support of modernized PMP estimates.

PMP DEFINITION

Based on a review and discussion of existing PMP definitions (Chapter 4, with supporting details in Appendix B), a review of PMP methods (Chapter 4), and assessment of user needs (Chapter 4 and Appendix D), the committee concludes that a revision to the current PMP definition is needed.

Recommendation 5-3: NOAA, federal and state agencies involved in dam safety and nuclear regulation, the American Meteorological Society, the American Society of Civil Engineers, and the Association of State Dam Safety Officials should adopt a revised PMP definition: Probable Maximum Precipitation—The depth of precipitation for a particular duration, location, and areal extent, such as a drainage basin, with an extremely low annual probability of being exceeded, for a specified climate period.

The committee notes that this definition of PMP is separate and distinct from the various methods for PMP estimation. This modern definition reflects a deliberate focus on the physical quantity—precipitation depth—which is defined for a specific duration and location and applied over a particular spatial scale for application (Figure 5-2). The depth is defined for a particular duration that is relevant for a user application (see Chapter 2 section on Spatial and Temporal Scales for PMP Estimates) and may be a function of season; durations typically range from 1 hour to 96 hours. The term “areal extent” is the spatial scale specific to an application. For dam safety applications, spatial scales typically range from 1 to 10,000 mi2 (Chapter 2). The 1 mi2 scale is also used for pluvial flood hazards at nuclear reactor sites (Chapter 2).

This precipitation depth is not an upper bound on rainfall but a depth with an extremely low annual probability of being exceeded (NRC, 1985, 1994). Extremely low annual probabilities have ranged from 10-4 to 10-7 for locations in the western United States (Box 4-2), which means that the depth referenced in the definition does not have a zero probability of exceedance. The extremely low AEP is not explicitly specified in the definition. Previous studies have suggested that the AEP of existing PMP estimates may vary by several orders of magnitude in the United States (Nathan and Weinmann, 2019; NRC, 1994; Schaefer, 1994) (see Box 4-2), at least for large watersheds and long durations. The selection of extremely low AEPs that define PMP can be achieved through guidance developed by the community.

Recommendation 5-4: Commensurate with the new definition, NOAA and the Federal Emergency Management Agency National Dam Safety Program, in partnership with federal agencies, states, and the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, should develop guidance for specifying AEPs for PMP that are acceptable for infrastructure decisions and society.

The depth of precipitation that defines PMP is a quantile of the distribution (Box 3-2) of annual maximum precipitation corresponding with the specified AEP. This AEP will be extremely low. The choice of AEP can vary by location, duration, and areal extent. As noted above, the AEP of PMP estimates based on near-term enhancements can be assessed using model-based methods (details are provided in the Model-Based PMP Estimation Section below). These estimates, which can be developed as part of the transition from near-term enhancements to model-based PMP estimates, will provide useful information for specifying the appropriate AEP values for PMP. Risk-Informed Decision Making (RIDM), nuclear reactor locations, and dam portfolios (Appendix C) are also important in selecting AEPs. The new PMP definition and model-based esti-

NOTES: The PMP basin-average depth is shown as a green dot in (a) with vertical and horizontal lines representing uncertainty in PMP depth and AEP, respectively. The spatial distribution of this 96-hour mean PMP depth over the watershed is shown in (b) with subbasins shown as black lines. Precipitation rates for each hour are shown in (c); vertical black lines are the start and end times for the 96-hour core precipitation period. The spatial distribution in (b) corresponds to the right vertical black line in (c).

SOURCE: Committee and Holman et al. (2019).

mation process restore the physical basis behind PMP and enhance the utility of PMP estimates for assessing design floods (Figure 5-2). For the watershed shown in Figure 5-2, model fields are used to estimate the precipitation distribution and uncertainty. Model-based methods can provide PMP estimates for a specified duration and areal extent, as well as the capability for resolving additional aspects of rainfall variability that affect flood risk.

The depth of precipitation is defined for a specified climate period. This climate period is a duration of time (in years) and may represent the present climate or a future climate (see additional discussion in the Model-Based PMP Estimation Section below). By specifying a climate period for a specified year or set of years, the PMP depth is representative of that time period. Estimates can change over time and with selection of the climate period.

PMP estimation is based on assumptions, data, and models. As with current PMP estimates, PMP estimates under this definition are subject to change as knowledge of the physics of atmospheric processes improves (WMO, 1986), to reflect new information, newer and larger extreme storm datasets, and improved observation and model-based constraints on potential rainfall increases in a warming climate. PMP is estimated with uncertainty. The estimates can be described in a range with upper and lower limits that quantify (approximately) the uncertainty.

This definition applies to any specific location or spatial area (such as a watershed), any time of interest (including different seasons or climate periods), and any duration of interest, and is independent of storm type. Revised PMP estimation procedures are recommended to fulfill the intent of this modern definition of PMP and to meet user needs. The Advisory Committee for Water Information, Subcommittee on Hydrology, Extreme Storm Events Work Group (ACWI, 2018, p. 32) recognized that a revision to the current PMP definition may be needed as PMP methods and assumptions are revised. As with previous PMP definitions, this new definition can be adopted by NOAA in consultation with major federal agencies—U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR), Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO)—and should replace the American Meteorological Society (AMS) Glossary definition.

NEAR-TERM ENHANCEMENTS TO PMP ESTIMATION

The long-term modeling framework will rigorously provide PMP estimates with robust scientific and statistical foundations. However, the full implementation of this framework may not be achieved in time to support some urgent needs. In the meantime, certain enhancements to present-day PMP estimation techniques are both needed and attainable. These enhancements will be based on improved data, expanded utilization of modeling, and the effective application of scientific understanding in implementing conventional PMP procedures.

Storm Catalog Data

Recommendation 5-5: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers should make its existing storm catalog publicly available. NOAA should facilitate digitization and enhancement of the existing storm catalog of historical extreme storms used in PMP for the United States to contain gridded rainfall fields and moisture data for each event. NOAA should facilitate development of an expanded storm catalog including high-resolution radar rainfall fields and available surface rainfall measurements for the United States to improve near-term estimation of PMP.

USACE, USBR, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and National Weather Service (NWS) have collaborated in various ways since the 1930s to collect and analyze storm rainfall data for PMP estimates (see example in Chapter 1 and summary in Chapter 3). The storm rainfall analyses, Depth-Area-Duration (DAD) data, and estimates of storm moisture for PMP have been used in the designs of most high-hazard dams in the United States. It is critically important to preserve the data from these “great storms” that represent the PMP-defining rainfall magnitudes in the United States. Preservation of data from these storms would facilitate comparisons of areal rainfall magnitudes from recent and future events, to assess increases over time and to quantify changes in PMP estimates.

These data are predominantly in paper and limited electronic formats from various Hydrometeorological Reports (HMRs), statewide and regional PMP studies, and some site-specific PMP studies. Full digital reproduction to gridded rainfall fields is recommended, with gathering, preserving, and archiving of surface observations and related data sufficient to reproduce the estimates. Individual storm rainfall centers, DAD summaries, moisture sources and influxes, and estimated transposition regions should be developed and archived for each event. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) would be an appropriate location for long-term storage, archiving, and maintenance of the extreme storm database (ACWI, 2018). The existing USACE extreme storm database (England et al., 2020) is a suitable prototype.

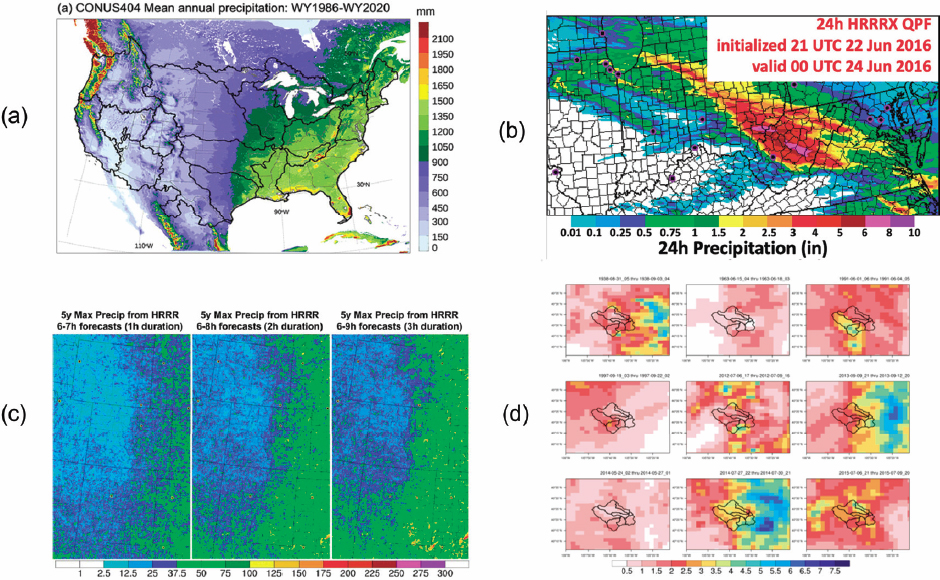

High-resolution rainfall datasets can be constructed from radar and surface rainfall observations to provide storm catalog data for the period from 1992 to the present (see Chapters 3 and 4 for discussion of key methodological details). Rainfall fields can be constructed with a spatial resolution of approximately 1 km and a temporal resolution of 5–15 minutes. The small spatial scale and short time resolution of rainfall fields are useful for addressing the ongoing challenge of PMP estimation for short durations and small areas (NRC, 1994). Although radar-based rainfall datasets will contribute to PMP estimation for all storm types, they will be most important in improving PMP estimates for convective storms, especially for time scales shorter than 12 hours and spatial scales smaller than 1,000 km2. The radar reanalysis dataset (Recommendation 3-1) will provide an important resource for identifying candidate storms for inclusion in the storm catalog.

High-resolution radar rainfall fields during the NEXRAD era (from 1992 to the present) will be a principal component of storm catalogs and provide an important

resource for near-term enhancements to PMP estimates. Because of phased deployment of radars during the 1990s and evolution of data archiving systems, near-complete records are not available prior to 2000. Radar coverage is also incomplete in some portions of the western United States, because of beam blockage in mountainous terrain (see additional discussion below).

For transparency in PMP estimation, methods used for computing rainfall from radar measurements and rain gauge observations should be standardized and documented. Procedures used for estimating rainfall from radar and rain gauges draw on a wide array of algorithms and assumptions, with quality control of both radar and surface rainfall measurements playing an important role (see Chapters 2 and 3). Documentation of methods used for development of high-resolution radar rainfall fields is critical for assuring that best practices are followed for transparency and accessibility of PMP estimates.

A time-consuming element of historical PMP studies has been the compilation of surface rainfall measurements (see Chapter 4). Surface rainfall measurements for storm catalog events should be a focus of data development activities, especially for the most extreme events that will control PMP estimates. Surface rainfall data should include conventional rain gauge measurements and all other measurements that can be obtained for a storm, including bucket survey measurements when available (e.g., Doesken and McKee, 1998). Similar attention should be paid to development of surface rainfall measurements for storm catalog events during the 1992–2024 period. Bucket surveys have not routinely been performed in recent years, but dense networks of gauges from the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow network (CoCoRaHS) and other volunteer observing platforms provide detailed depictions of the spatial distribution of rainfall for durations of 1 day or longer.

Recommendation 5-6: NOAA should develop procedures for obtaining and validating surface rainfall measurements for PMP studies.

High-resolution radar rainfall fields during the period 2000–2024 can provide an important data resource for evaluating modeling systems developed for PMP estimation (see section on Model Evaluation Project below). The radar reanalysis dataset (see Chapter 3), which should be nearly complete for the period 2000–2024, provides observations that can be used to assess model simulations of current climate rainfall extremes across much of the United States. Intercomparisons between model simulations and high-resolution rainfall fields can be used to address the performance of models in simulating extreme rainfall for different storm types, especially for tropical cyclones (TCs) and convective storms. Intercomparisons can also contribute to regional assessments of model performance, especially for regions of complex terrain (mountainous regions, land-water boundaries, and urban environments).

Incomplete coverage by radar in mountainous terrain imposes geographic limitations on model assessments for mountainous regions. The “half-full glass” perspective on mountainous regions is that most radars in and adjacent to mountainous terrain can provide useful data for subsets of the radar coverage area. The Denver, Colorado,

radar, for example, provides good coverage of portions of the Front Range, which has a complex history of PMP estimates (e.g., Friedrich et al., 2016).

For the polarimetric radar era (2013–present), high-resolution rainfall fields can be augmented by 3-D polarimetric fields for assessing model performance. These observations have proven especially useful in evaluating the capability of models to represent microphysical processes in extreme rain (Ryzhkov et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2019).

High-resolution radar rainfall fields can contribute to ongoing monitoring of rainfall extremes, including assessments of climate change impacts. Ongoing development of the radar rainfall datasets beyond 2024 will provide expanding observational resources for PMP analyses. Longer datasets will enhance the ability to assess performance of model simulations. They will also provide an observational base for assessing climate change impacts on rainfall extremes. NOAA will need to periodically evaluate the observed effects of climate change on rainfall extremes. The high-resolution rainfall fields will be especially useful for short-duration rainfall extremes, one of the biggest challenges for climate change assessments (Chapter 3).

Reconstruction of Rainfall Fields for Key Events in the Historical Storm Catalog Using Model Simulations

Recommendation 5-7: NOAA should facilitate model simulations of historical storm events that (1) may be added to the expanded storm catalog, (2) enhance scientific understanding of PMP-magnitude storms and their precipitation distributions, and (3) contribute to the Model Evaluation Project.

Many of the storms that are currently used in PMP estimation occurred long before the advent of weather radar and other modern meteorological tools. As a result, the spatial and temporal distributions of precipitation in these events have been reconstructed, generally from sparsely located rain gauge measurements and “bucket surveys.” The levels of confidence in these historical reconstructions vary, yet they represent the primary control on PMP in many regions. Retrospective analyses of these historical storms are not consistently accessible to the scientific community, because they have been developed by various agencies/companies and stored in a multitude of locations and formats.

In the 21st century, polarimetric weather radars and advanced algorithms to convert observed radar variables to rain accumulations have enabled much more detailed analyses of extreme rainstorms. Yet these methods also have uncertainties, especially in complex terrain where radar beams may be partially or fully blocked. Rain gauge coverage is generally greater now across the continental United States (CONUS) than in the past owing to efforts such as the CoCoRaHS network, yet gauge coverage is uneven, with highly populated areas having many more gauges than rural areas. Thus, consistently processed, publicly available simulations of historical PMP-magnitude storms are needed.

Model reconstructions of historical PMP-magnitude storms represent one method for enhancing storm catalogs in the near term, while also serving other purposes. Evalu-

ations of model-simulated events that occurred during the radar era could be used to document existing strengths and weaknesses of numerical models for simulating PMP-type events. This task is the foundation of the MEP (see Model Evaluation Project section below), which represents one step in transitioning from near-term enhancements to PMP estimation to a fully model-based approach to PMP estimation. Simulated storm reconstructions will also be useful for supporting other near-term enhancements to PMP estimation (see further discussion in the following sections).

A promising approach for enhancing storm catalogs is to reconstruct each storm in the catalogs through the use of ensembles of high-resolution simulations with convection-permitting models, driven by global historical reanalyses, and produced by running multiple simulations with slightly different initial conditions or model configurations. Mahoney et al. (2022) demonstrated that this approach is possible for some PMP-controlling storms, most notably atmospheric river (AR) events with topographic focusing of extreme rainfall. For such simulations to be useful in near- and long-term efforts to enhance PMP estimation, simulations need to represent the general spatial distribution and magnitude of extreme rainfall in the region where it was observed, but they do not need to exactly replicate the location and timing of the event. Mahoney et al. (2022) noted that some historical events eluded successful simulation; short-duration, small-area rainfall extremes are especially challenging. So, while promising, expanding such model-based storm catalog information will require further research and development to improve models, determine whether data assimilation is needed/beneficial, and identify best practices for this approach.

Efforts to develop model-based entries to storm catalogs should begin with recent storms for which polarimetric radar data are available. The polarimetric data permit a comprehensive evaluation of simulations of these storms, enabling assessment and enhancement of the model configurations. Enhancements can contribute to reconstructions of historical storms that control or approach PMP, and for which high-quality detailed reconstructions are not currently available. These would include challenging events such as the Smethport, Pennsylvania (1942) and D’Hanis, Texas (1935) storms that control short-duration, small-area PMP estimates over large regions. These efforts should encompass a range of storm types that are known to produce PMP-magnitude precipitation accumulations, including ARs in the western United States and Alaska; “upslope” storms in the Rocky Mountains, Black Hills, and Appalachians; TCs in the southern and eastern United States and Hawaii; and mesoscale convective systems in the central and eastern United States. Strengths and limitations of existing reanalyses and models must be identified first, along with systematic approaches for reconstructing these events with numerical models. Besides the need to identify strengths and limitations, there is the need to improve initial conditions, forcing data, models, and experiment design beyond present-day best practices. As shown by Mahoney et al. (2022), current methods for generating model initial conditions may not be sufficient, especially for simulating short-term, localized storms.

Methods: Storm Types, Storm Transposition, Maximization and Transposition Factors, Envelopment

Recommendation 5-8: NOAA should include a summary of scientific principles in its national guidance for near-term PMP estimation. Near-term enhancements to storm transposition, moisture maximization, and transposition factors—especially for components involving subjective decisions—should be grounded in advances in scientific understanding, as detailed in this guidance.

Components of the conventional PMP methods can be highly subjective, are not transparent, and cannot be reproduced independently (Chapter 4). Therefore, near-term enhancements are needed to improve the clarity and objectivity of current PMP methodology.

Storm Types

The proposed model reconstruction dataset (see section on Reconstruction of Rainfall Fields above) can be exploited to make systematic connections between storm types and PMP-magnitude rain accumulations. The development of updated storm catalogs should include scientifically informed characterization of storm type. The combination of radar data and model output (including reconstructions of historic storms), along with machine learning (ML) classification techniques, should enable characterization to be done in a systematic way. ML can efficiently identify storm types when applied to this type of model output, and the spatial and temporal comprehensiveness of this dataset will make the results even more robust, compared to existing datasets that generally have gaps in space, time, or both. The findings of these studies can then be applied back to observational datasets as they are expanded and further developed.

Storm Transposition, Terrain and Orographic Adjustments

Sensitivity studies have illustrated the key role that storm transposition plays in determining PMP estimates (Micovic et al., 2015). The practice of storm transposition has centered on subjective decisions based on scientific reasoning applied by PMP practitioners (Chapter 4). Storm transposition is developed storm by storm and requires a deep understanding of the individual storms that are to be transposed and the meteorological circumstances in which they can occur. Determination of storm transposition regions also requires the ability to place the storm within the larger population of extreme storms in the region. Model reconstructions of storm catalog events, as detailed above, provide an important tool for developing the scientific understanding of individual storms needed for determining storm transposition regions.

For storm transposition, it is critical not only to define transposition regions, but also to understand how the moisture, terrain, and orographic adjustment should be applied during the transposition. The large number of reconstructed storms with detailed information of the storm characteristics and their environments can be used to analyze

and categorize storms with similar drivers, and to summarize how the simulated rainfall depth may change across different terrain and orographic conditions. The information may be used to revise and simplify the conventional storm separation method into a more reproducible topography adjustment procedure. The efforts should also include an assessment to determine how to utilize precipitation frequency estimates (e.g., NOAA Atlas 14 and 15) for orographic adjustment, either in terms of simple ratios or in other empirical equations. Additionally, a comprehensive understanding of their strengths and limitations is crucial.

Moisture Maximization

In terms of moisture estimates, the current methods based on surface dew point are highly subjective and difficult to reproduce. Although individual surface dew point observations can still be useful to estimate moisture for small-scale, short-duration storms, they may be insufficient for large-scale, long-duration storms in which the incoming moisture range can be extensive and dynamic. In such conditions, a more reasonable approach would be to estimate dew points or precipitable water (PW) over a large region, leveraging reanalysis datasets. Therefore, we envision modifications to the moisture calculations from two aspects. First, an enhanced dew point or PW selection procedure should be established. The procedure should provide clarity for independent verification, to enable easy confirmation of whether all selection criteria such as reasonable timing of moisture arrival are met.

Second, the calculation of moisture should account for storm type. For example, for continental convection (e.g., “local storms”), the use of surface dew point measurement may be most appropriate, because precipitation amounts are highly sensitive to the near-surface water vapor and there is often drier air aloft. In contrast, for TCs and ARs, where moisture transport over a deep layer is important to the intensity and distribution of rainfall, the vertically integrated water vapor (i.e., PW) provided by meteorological reanalysis datasets is likely a more appropriate variable to use in moisture maximization. While the direct measurements of PW are much less dense in space and time, modern data assimilation systems that combine model, satellite, and other information have enabled detailed reanalyses such as ERA5, which has global coverage and hourly time resolution. Although it is clear that the coarse resolution atmospheric reanalysis may be insufficient to represent local extreme rainfall processes (e.g., Zhang et al., 2023), it is expected that the storm environments, including the PW, are sufficiently well represented for use in moisture maximization calculations. Further research is needed to determine whether ERA5 is sufficiently accurate to be used to estimate PW for PMP calculation, and what specific processes and guidelines should be established for of its application to PMP.

Updated climatological information (i.e., frequency estimates) on surface dew point and PW should be used in modernized PMP estimation. When developing dew point climatology maps from point-based dew point observations, apart from including decades of additional measurement since the development of HMRs, best practices developed for extreme precipitation frequency analyses such as NOAA Atlas 14 should be followed.

In addition to the final dew point climatology maps for applications, this effort should also provide verifiable information on data processing, computation, smoothing, and quality control. Development of a PW climatology should involve evaluation of various choices of reanalysis datasets and determination of the most appropriate ones for application. What frequency level should be used in the climatology calculation should also be clarified. As a reminder, the choice between a 100-year return level and +2σ in the current practice seems inconsistent and arbitrary.

To date, the climatologies of dew point that have been used for PMP estimation in the United States have assumed that there is no underlying moisture trend. However, as the climate changes, expected extreme values of dew point or PW should change as well, partly because of the same thermodynamic relationship that leads to the expected increase in precipitation intensity with higher temperatures. Changes in extreme PW and dew points have indeed been observed across the United States (Kunkel et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021; Scheff and Burroughs, 2023; Su and Smith, 2021). As a consequence, moisture maximization that is based on a stationary statistical analysis of historical dew point or PW tends to underestimate the maximum moisture that will likely be available to such a storm in the present, warmer climate.

So that PMP can be valid for the present-day climate, the dew point and PW climatologies should be created assuming nonstationarity, using estimates of the impacts of climate and land use change on dew point and PW. Moisture maximization of each storm would then be based on a suitable return period for moisture given present-day climatic and land use conditions. Such a practice would account for the bulk of the expected effects of climate change on PMP during the historical period.

Envelopment

Envelopment may be needed and should be used in the near-term enhancements approach to PMP estimation. Envelopment is particularly important to compensate for the limited number of near PMP-magnitude events in the storm catalog and sparse spatial coverage of storms, particularly in the western United States. Envelopment should be applied after transposition and maximization, with consideration of storm spatial and temporal scales. Sharp gradients and discontinuities that can occur at state or regional boundaries due to fixed transposition limits should be investigated and possibly removed with envelopment and regional smoothing.

Uncertainty Characterization

For the near-term enhancements approach, which is based on the current PMP practice of storm transposition and maximization, the committee sees no way to produce statistically sound uncertainty estimates.

In the near term, the committee recommends a combination of simple sensitivity analysis (e.g., varying one parameter at a time and quantifying variability in the result) and Monte Carlo–based sensitivity analysis. The simple sensitivity analysis is advanta-

geous because it makes clear that the uncertainty derives from lack of certainty about key inputs. The Monte Carlo–based analysis is advantageous because it integrates the effects of lack of certainty about multiple inputs. However, neither approach has the standard statistical interpretation of statistical coverage (i.e., confidence), and presentations of uncertainty should emphasize that the uncertainty is driven by the variability quantified in the experts’ input distributions.

Comparisons between PMP estimates and maximum rainfall accumulations (as in Riedel and Schreiner, 1980), using data through 2024 (see additional discussion in Chapter 4), are also useful. Such comparisons can identify regions with relatively large apparent inconsistencies between the results of the two approaches.

Climate Change Adjustment Factors

The Chapter 3 section on Scientific Advances: Climate Change and Extreme Rainfall discussed how physical understanding, historical trends, and model simulations and projections all point to an increase in extreme precipitation with warming. Therefore, PMP is expected to increase in the future, because climate models project global warming to continue under all socioeconomic scenarios with increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases. Hence the near-term enhancements approach using conventional PMP methods should be augmented to account for the changes in PMP with future warming. By applying an adjustment factor to the PMP estimates of the present-day climate, the PMP in a future period can be estimated based on the nonlinear power law scaling of extreme precipitation with temperature as follows (Hardwick Jones et al., 2010).

PMPfuture = PMPpresent (1 + α)ΔT

Here, PMPpresent and PMPfuture are the PMP estimates for the present-day and future climate, respectively, (1 + α)DT is the adjustment factor, ΔT is the change in surface air temperature (K) between the future and present-day periods, and α is the scaling of extreme precipitation with temperature (%/K). The adjustment factor can be calculated for a particular geographic area or region. With global mean surface temperature commonly being used in the scaling relationship (e.g., Figure 3-4), here for consistency in calculating the adjustment factor, ΔT can be estimated based on the global mean surface temperature simulated by global climate models. However, other temperature or thermodynamic variables, such as regional mean surface temperature and dew point temperature, have also been used to derive the scaling relationship. Although there is a need to further investigate the use of different variables and their spatial scales for the scaling relationship, the ΔT used in calculating the adjustment factor should be consistent with the temperature used in the scaling relationship.

Several mechanisms that influence the scaling relationship between extreme precipitation and temperature are important to consider in estimating α.

- With no change in atmospheric circulation, storm dynamics, and relative humidity, extreme precipitation is expected to increase with warming at roughly the C-C rate (~7%/K) that dictates the increase in saturation vapor pressure with temperature.

- As a result of the lapse rate effect reflected in larger warming at higher altitudes (Emanuel, 1994), the increase in atmospheric stability reduces precipitation intensity.

- Increase in latent heat release due to increased moisture and condensation intensifies storms and extreme precipitation.

- Reduced near surface relative humidity over land, a robust signature of global warming (Byrne and O’Gorman, 2016; Zhou et al., 2023), increases convective inhibition (CIN) that allows moist convective energy to build up over a longer period before it is released in more energized storms (Rasmussen et al., 2017).

- Changes in precipitation efficiency with warming related, for example, to changes in cloud microphysical processes due to how efficient cloud condensates are converted to precipitation (Lutsko and Cronin, 2018).

While (1) is robust and influences storms in similar ways, the impacts of (2)–(5) would depend on the dynamical regimes and storm types (e.g., Muller, 2013), the duration of precipitation extremes (e.g., hourly vs. daily), and the extreme precipitation percentiles being analyzed. For extreme precipitation associated with convective storms, increase in latent heat release and CIN with warming will likely intensify the extreme precipitation beyond the C-C rate, particularly for the short duration and high percentile extreme precipitation (Berg et al., 2013; Haerter et al., 2010). For cold season orographic extreme precipitation related to ARs, the elevated warming with altitude may shift the extreme precipitation downwind for a larger fractional increase in extreme precipitation on the lee slope than on the windward slope of mountains (Siler and Roe, 2014). For PMP, the relevant scaling relationship α should be for events with extremely low probability of occurrence (e.g., < 0.001). Because theories and observational and modeling studies suggest that α increases with increasing precipitation percentile (Figure 3-4), using a spatially uniform value of α corresponding to the C-C scaling of 7%/K is likely a conservative starting point for the adjustment factor to account for the effect of global warming on PMP.

Given the various complex mechanisms that influence the scaling relationship, α may be more robustly estimated based on modeling to address both thermodynamic and dynamic changes, leveraging the convection-permitting model (CPM) capability that will be used for the reconstruction of historical PMP storms, as discussed above. To estimate α, the pseudo-global warming (PGW) approach (Schär et al., 1996) can be used to simulate the reconstructed historical storms under the future climate by adding perturbations to the initial and boundary conditions to account for the future changes in the environments as projected by global climate models. Changes in precipitation for the reconstructed storms in the historical and future environments and the change in the surface temperature can be used to provide an estimate of Symbol for adjustment of the PMP for the future climate. Alternatively, long-term (decadal) CPM simulations

can be performed using the PGW approach to determine the change in precipitation intensity for different probabilities of occurrence at each model grid cell. Using these simulations, α can be estimated based on the simulated precipitation intensity change for different percentiles and the change in surface temperature. The estimated α at each grid cell can also be averaged to provide an estimate of α for different climatic regions (e.g., Vergara-Temprado et al., 2021). While regional temperature has been used more often in regional modeling studies, using global mean surface temperature in estimating α offers a convenient way to calculate the adjustment factor for different socioeconomic scenarios and global warming levels because ΔT can be obtained from multi-model climate projections (e.g., from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) (Eyring et al., 2016)) for different socioeconomic scenarios or global warming levels, even if PGW simulations may be available for only a single scenario to estimate α. Although modeling has inherent biases and uncertainties, it can account for the various mechanisms that influence α and allow for sensitivity experiments to provide additional insights on α and its uncertainties (e.g., Lenderink et al., 2021).

Recommendation 5-9: For near-term enhancements to PMP estimation, NOAA should adopt climate change adjustment factors based on the model-based scaling relationship between extreme precipitation and temperature.

MODEL-BASED PMP ESTIMATION

Advances in atmospheric and climate modeling and innovations in software engineering and computing infrastructure over the past decade (see Chapter 3 section on Numerical Modeling and Computing) have enabled the running of kilometer-scale climate simulations on high-performance computer architectures. Here kilometer-scale simulations refer to simulations produced at model grid spacing roughly between 1−5 km, often referred to as convection-permitting simulations. With demonstrated improvements in modeling various types of storms that could produce PMP compared to coarser-resolution models (e.g., Ban et al., 2014; Kendon et al., 2021; Mahoney et al., 2022; Prein et al., 2015; Rasmussen et al., 2023; Stevens et al., 2019), it is feasible in the longer term to modernize PMP estimation by using regional and global kilometer-scale models for PMP estimation.

Modeling offers several advantages over the conventional, largely data-driven approach outlined above for the near-term enhancements to PMP estimation, from several perspectives:

- With sufficient length and ensemble size, model simulations provide a more complete record of PMP events that are not available from the limited observational record, especially in regions with complex terrain;

- Simulations provide the full space-time fields, enabling estimation of PMP for any spatial area, location, and duration, as well as estimation of the spatial distribution of PMP;

- With the plethora of data from the model simulations, PMP can be estimated

- using methods that are less reliant on expert judgment, such as approaches for storm transposition and orographic adjustment;

- The calculation of uncertainty in the model-based PMP estimates becomes easier with ensemble simulations;

- With models capturing the physical processes associated with PMP storms and their responses to climate change, modeling offers a more straightforward approach to PMP estimation under different climates; and

- Through analysis of the model simulations and projections, model-based estimates of PMP and its future changes can be combined with narratives of the future scenarios and physical explanations of the underlying processes, potentially improving stakeholder communications regarding PMP estimation in a changing climate.

Based on assessment of the current and evolving state of modeling and computing, modeling approaches to PMP estimation in the present-day and future climates are discussed in the Long-Term, Model-Based PMP Estimation and Climate Change sections below. The committee recommends an MEP to rigorously evaluate, compare, and document different model-based approaches for estimating PMP to assess readiness to adopt model-based approaches (see section on Model Evaluation Project below). Such scientific evaluation should be complemented by a statistical assessment of the simulation length and ensemble size needed for model simulations and projections to provide a sufficiently complete record of PMP-magnitude events for PMP estimation (see sections on PMP Estimation: Extreme Value Methods and Power Analysis/Sample Size Determination below), as well as an assessment of the computational feasibility for performing those simulations and projections on the next-generation computational platforms.

Long-Term, Model-Based PMP Estimation

With a focus on the geographical region of the United States, both regional and global kilometer-scale models or CPMs can provide scientifically supported model-based estimates of PMP if found to be fit-for-purpose through the MEP. Regional modeling, an approach that is more generally known as dynamical downscaling, refers to the use of numerical weather and climate models to produce high-resolution simulations consistent with the large-scale conditions depicted by global reanalysis or simulated by lower-resolution Global Circulation Models (GCMs). Both regional models (a.k.a. limited area models) and global models with regional refinement can be used for dynamical downscaling to produce kilometer-scale simulations for regions of interest (Gutowski et al., 2020). The latter has emerged in the past decade with methodological advances in generating unstructured meshes for computational modeling. In limited area models, large-scale constraints are provided through the lateral boundary conditions. In global variable-resolution models, large-scale circulations are downscaled to higher resolutions within the refined domain, but the finer-scale processes simulated therein have upscale impacts on the large-scale circulation outside the refined regions (Sakaguchi et al., 2015, 2016). Modeling processes across scales within the global

variable-resolution modeling framework places a stronger requirement for the physics parameterizations to be scale aware.

Besides dynamical downscaling, it is now feasible to run kilometer-scale climate simulations using global CPMs on large supercomputers (Bolot et al., 2023; Stevens et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2023). Global CPMs have the potential advantage of improving modeling of the large-scale circulations, which may improve simulations of precipitation within the United States, when compared to the use of regional refinement in which the large-scale circulations are largely governed by the lower-resolution simulations outside the refined domain.

To provide model-based estimation of PMP consistent with the updated definition, initial-condition large ensemble simulations (Deser et al., 2020) are needed to estimate the depth of precipitation with an extremely low AEP. By perturbing the initial conditions, which may be achieved by initializing the simulations on different dates or by adding small random noises to the initial conditions of the atmosphere, large ensemble simulations can be produced to account for uncertainty arising from natural variability and provide more robust estimation of precipitation events with very low probability of occurrence. For dynamical downscaling, limited-area models and global variable resolution models with regional refinement can be used to downscale GCM large ensemble simulations to provide the boundary conditions. For global CPM, large ensemble simulations can be produced using kilometer-scale atmosphere models coupled to eddy-resolving ocean models, or kilometer-scale atmosphere models driven by sea surface temperature and sea ice from lower-resolution coupled GCM simulations, depending on the readiness and computational feasibility of the former.

Although kilometer-scale coupled models hold great promise in transforming our ability to simulate the climate system with high fidelity and great details, running such simulations requires new strategies for model spin-up; the computational resources needed for the standard approach used by GCMs to run 500+ years of pre-industrial simulations from cold start for model spin-up are likely prohibitive for global CPM even with exascale computers. For global simulations, kilometer-scale atmosphere simulations driven by sea surface temperature and sea ice from lower-resolution coupled GCM simulations are more viable at the initial stage of adopting the long-term approach. To address multiple sources of uncertainty, multi-model initial-condition large ensemble kilometer-scale simulations are desired for quantifying uncertainty associated with both models and internal variability. As advances continue to be made in artificial intelligence (AI)/ML techniques and their trustworthiness, kilometer-scale modeling may be blended with AI/ML approaches to potentially improve model fidelity and computational efficiency. Such blending may include use of ML-enhanced parameterizations and numerical solvers in models, ML methods such as emulators for model calibration and uncertainty quantification, and ML emulation for ensemble boosting, which is particularly useful for augmenting the large ensemble kilometer-scale simulations. For example, an ML emulator of a low-resolution global atmosphere model was able to produce stable multi-year-long simulations (Watt-Meyer et al., 2024), hinting at the potential for ML techniques to be used in ensemble boosting. Trained using kilometer-scale simulations, the ML emulator can be used to increase ensemble size at much lower

computational cost compared to kilometer-scale modeling, if the ML emulator is capable of simulating PMP-magnitude storms with appropriate frequency.

Climate Change

Model-based approaches are more amenable to directly estimating PMP under different climate conditions than current PMP estimation methods because models can produce simulations of PMP events consistent with the climates under different external forcings. This approach represents an improvement over the adjustment factor recommended for the near-term enhancement approach because surface temperatures do not uniquely determine precipitation characteristics. Different forcing agents, such as greenhouse gases and aerosols, are expected to have different effects on both weather patterns and on physical processes within storms (e.g., Fan et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2022) resulting in different mean and extreme precipitation trends (Rai et al., 2023; Risser et al., 2024). The large ensemble simulation approach for estimating PMP in the historical climate can be extended to produce large ensembles of kilometer-scale regional (downscaling from large ensembles of GCM projections for the future) and global simulations under different socioeconomic scenarios or global warming levels for PMP estimation under the future climates. Such simulations can naturally provide a large number of PMP-magnitude events to estimate the changes in PMP. Table 5-1 summarizes the historical and future simulations for model-based estimation of PMP for different climate periods. A potential constraint for this approach is the computational demand for running multi-model large ensembles of kilometer-scale simulations for multiple socioeconomic scenarios (e.g., SSP5-8.5 and SSP2-4.5 representing two contrasting socioeconomic pathways and different radiative forcing by 2100). However, similar to ensemble boosting for the present-day simulations, ML emulators can be trained using kilometer-scale simulations for the future climates to address the out-of-sample issue. Ensemble boosting using ML emulators is a computationally efficient way to augment large ensemble kilometer-scale simulations, providing enough samples of PMP events under both current and future climates for a potentially viable approach for estimating PMP with uncertainty and without storm transposition.

Although the recommended initial-condition large ensemble kilometer-scale simulations incur significant computational requirements, they are critical not only for modernizing PMP estimation but also for addressing a much broader set of questions related to extreme weather risk in a changing climate (PCAST, 2023). The grand challenge of producing such simulations calls for broad collaborations among government agencies and between the government, academia, and private sectors to accelerate progress that supports planning for a climate-resilient society.

Recommendation 5-10: In the long term, NOAA should adopt a model-based approach to PMP estimation that aligns with the revised PMP definition, consisting of multi-model large ensemble kilometer-scale or finer-resolution modeling to construct the probability distribution of precipitation for PMP estimation under different climates.

PMP Estimation: Extreme Value Methods

With the large ensemble model runs discussed above, high frequency (sub-hourly to hourly) precipitation at kilometer-scale grid spacing will be available for a large ensemble of simulations covering at least 30 years for the historical period (e.g., 1981–2010) driven by historical forcings and the future periods (e.g., 2041–2070 for the mid-century) driven by various socioeconomic scenarios. Each member of the initial-condition large ensemble represents a plausible realization of transient climate consistent with the imposed time-dependent external forcings. Given sufficient precipitation data (for each climate period), one could directly estimate AEP depths for small, but not extremely small probabilities using empirical quantiles (e.g., for the 0.001 AEP depth, which is the value for which 0.1% of the annual maxima of the observations exceed the value). For more extreme PMP-relevant probabilities, extreme value methods are necessary because the number of years of modeled output is too short for direct estimation. In extreme value analysis (EVA), AEP depths depend solely on the parameters of the extreme value distribution and are driven particularly by the shape parameter. In fact, one can estimate the shape parameter with some precision even without massive amounts of data. We discuss the sample size required to achieve a specified precision below. This provides hope for estimating even fairly extreme quantiles (and for return periods much longer than the length of time the model has been run for) with moderate uncertainty. Of course, there is no free lunch; such estimation relies on the assumptions that justify use of extreme value distributions compared to approaches that do not rely on assuming a particular distribution.

Recommendation 5-11: For the long-term approach and in agreement with the recommended PMP definition, NOAA should use statistical approaches to estimate PMP (with associated uncertainty) as the precipitation depth corresponding to an extremely low annual exceedance probability from the model-simulated precipitation distribution, with particular consideration of extreme value analysis based on threshold exceedance methods.

When using model output one can directly estimate AEP depths at each grid point, or for each drainage basin or other area of interest, as well as for each duration of interest. Specifically, if a stakeholder is interested in estimation for a particular spatial area and duration, provided they have the full model output (or potentially model output limited to the occurrence of extremes, which can be used in threshold exceedance analysis) they can obtain the necessary extreme precipitation observations at the spatial/temporal domain of interest.

It is reasonable to assume that AEP depths should be relatively smooth in space and that the degree of smoothness will vary with topography. Individual grid cell estimates may not vary smoothly because of uncertainty associated with the parameter estimates arising from limited sample size. In particular, noisy estimates of the shape parameter can result in spatially noisy AEP depth estimates.

If estimates are not deemed to be sufficiently smooth in space (or perhaps with respect to duration), then the need arises for longer model runs or for analysis that bor-

rows strength across locations (i.e., regionalization) to smooth the estimates, thereby reducing statistical uncertainty. Local likelihood, regional frequency analysis, or spatial statistics are potential methodological options to achieve smoother estimates. Alternatively, the estimates could be smoothed using simple non-statistical techniques, such as inverse distance weighting.

In regions of complex topography, how to do the smoothing is more troublesome, because it becomes more difficult to select comparable locations with similar climatology and therefore similar AEP depths. One possibility is to use data on less extreme precipitation to characterize areas that experience similar precipitation frequencies. This could then, for each location, provide a spatial area in which the practitioner is comfortable smoothing/borrowing strength.

Storm Types and Threshold Exceedance Estimation

Estimation of the extreme value parameters is affected by a statistical bias-variance tradeoff. As the block size or threshold is increased, the data is expected to be better approximated by an extreme value distribution, thus reducing bias, but with increased variance from the decrease in the number of observations.

With daily data, a sample size of 365 days in a block is generally considered sufficient for use of the Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) distribution in many applications. The situation is more complicated with PMP-magnitude precipitation. Such precipitation may be driven by conditions that rarely occur, even over the course of an entire year. As discussed in Chapter 3, extreme precipitation in many locations and seasons is likely caused by a variety of storm types, and use of annual maxima could mix precipitation observations coming mostly from less extreme storm types with fewer observations from the type that generates the largest extremes. Inclusion of data arising from storm types with a lighter tail would bias estimation of the shape parameter associated with the storm types that lead to PMP-relevant events. Thus, for estimation of AEP depths for extremely small probabilities using model output, the threshold exceedance approach seems most appropriate, with the threshold chosen to exclude events that are not truly extreme—in particular those events from storm types not expected to produce precipitation amounts in the far tail of the distribution. Alternatively, given that the block maxima approach can be more straightforward (e.g., not requiring one to consider temporal declustering), a block size larger than a year could be selected. However, eliciting information from experts about the block size is less direct than eliciting information about magnitudes associated with different storm types for use in determining a threshold. Furthermore, threshold exceedance analysis lends itself to a data reduction strategy of only saving model output for days (or days and regions) in which extreme precipitation occurred somewhere in the United States.

Conclusion 5-2: Estimation of PMP using extreme value methods should employ the threshold exceedance approach, using a threshold sufficiently high to rely pri-

marily on precipitation from events that produce the most extreme precipitation, in order to limit statistical bias.

Once a threshold (or block size) is chosen, the statistical estimation strategy described above does not use information about storm types. However, in cases where multiple storm types could each produce PMP-magnitude precipitation, statistical consideration of mixtures of distributions corresponding to different storm types may be appropriate.

Climate Change

The proposed extreme value methods discussed above for PMP estimation are best suited for data that are assumed stationary. The specific analysis of simulations accounting for climate change will need to be tailored to the model data that are produced for PMP estimation. If long model runs are produced with a transitory climate, then the analysis will likely need to account for the nonstationary climate represented in the model output. The most straightforward statistical approach would be to include a linear trend in one or more of the three parameters of the extreme value distribution. A common approach attempts to account for nonstationarity by first building a trend into the location parameter, and then increasing model complexity if necessary by adding a trend to the scale parameter (or log scale because scale must be positive). However, with multiple replicates (an ensemble of runs), trends in all parameters could potentially be investigated. As a first-order approximation, a linear trend may be reasonable provided the time interval is not too long and/or the change in forcing not too strong. If climate change is instead addressed by producing ensemble model runs of shorter time periods under different climate scenarios, a stationary model could be fit to each scenario individually. There could still be statistical modeling choices to be made such as whether the shape parameter would be better estimated by assuming a common value for all scenarios or whether it should vary with climate. Such a choice is similar to whether the shape parameter is allowed to vary in a nonstationary model fitting.

Sample Size Determination

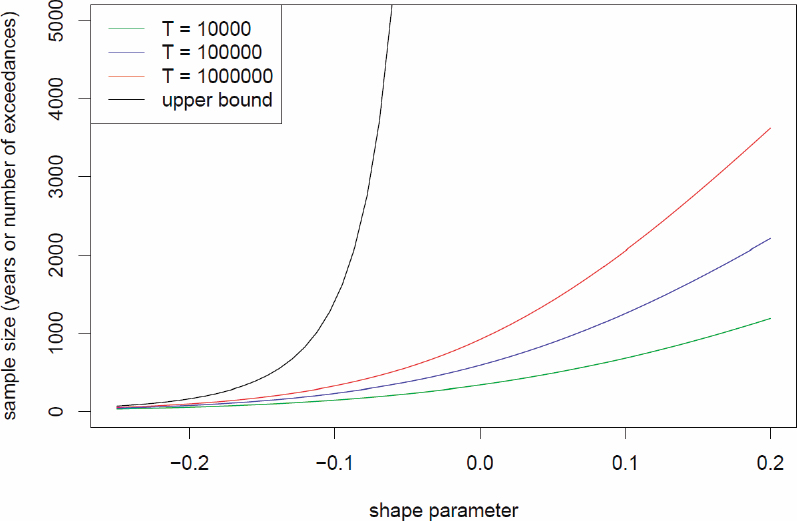

Intuitively, estimating an AEP depth for a small probability (a high quantile) will require a large sample size (many years of model output from a long model run or ensemble). Using standard likelihood-based statistical calculations (Coles, 2001), one can estimate the number of years of data needed to achieve a given level of precision in the estimated AEP depth under the assumptions underlying the use of extreme value methods (Chapter 3). This calculation relies on standard likelihood theory, using the relationship between the variance of the estimated AEP depth (which scales inversely with the sample size) and the estimated information matrix for the extreme value distribution parameters (see Box 3-2). Figure 5-3 presents the results of an example sample size analysis, indicating that the needed sample size increases with the shape parameter

and with the use of more extreme probabilities. Estimation of an upper bound (where it exists) requires a much larger sample size than even very low probability AEP depths.

This sample size analysis assumes that using a block size of 1 year would produce yearly maxima that are representative of extreme precipitation and that could be treated as coming from a single extreme value distribution. As discussed above, for precipitation in some regions and seasons, that assumption is very likely to be violated, and the committee recommends use of the threshold exceedance approach. For a given location, season, and duration, it may be important to understand which storm type(s) produce PMP-magnitude precipitation to determine an appropriate threshold for use in a sample size analysis.

A sample size analysis for threshold exceedance modeling can be conducted as follows. If the threshold is taken to be the AEP depth for some (less extreme) probability, then it is straightforward to show that the sample size calculation for the GEV distribution is equivalent to the sample size calculation for the point process-based approach to the threshold exceedance model (see Chapter 7 in Coles, 2001 for details on the point process model), with the critical difference that instead of needing “x” years of data, one needs “x” exceedances (as indicated by the y-axis label of Figure 5-3) for a given desired precision. Thus, the number of years of data needed for a threshold exceedance analysis scales inversely with the probability of an exceedance in a given year. For example, if an exceedance occurs on average every 10 years (a 10% probability in a year), then 10 times as many years of data are needed as if yearly maxima were being used. This makes intuitive sense, because the information in the data scales with the sample size.

Uncertainty Estimation

In contrast to the difficulty in quantifying uncertainty with current PMP methodology, quantifying sampling uncertainty in EVA-based AEP depth estimates can be done using well-established statistical methods, particularly when the analysis is done location by location and duration by duration without any borrowing of strength. The simplest approach is to use standard likelihood-based confidence intervals (see Box 3-2) or confidence intervals based on the profile likelihood (Obeysekera and Salas, 2014, 2016; Zhang and Shaby, 2022). Other approaches are also possible, for example, bootstrapping in conjunction with any estimation method (e.g., likelihood or L-moments) or Bayesian approaches. The amount of uncertainty will be driven by the sample size (i.e., the number of years of model output or number of exceedances, from one or more model runs) and can be decreased if needed by additional model simulations. Estimation of uncertainty when using procedures that borrow strength across locations would need to account for spatial dependence in the data arising from the fact that multiple locations see the same storm. Full accounting of this dependence in extreme value modeling is presently challenging and an area of research, but storm dependence could be accounted for with bootstrap approaches.

NOTES: The sample size is the number of years if conducting a block maxima analysis and the number of exceedances if conducting a threshold exceedance analysis needed in order for the standard error of the estimated AEP depth (or upper bound) to be less than 12.5 percent of the value of the AEP depth. Results are shown for several different AEPs, corresponding to return periods of T = 104, 105, and 106 years (or upper bound). The constraint of 12.5 percent is equivalent to the length of a confidence interval being less than 50 percent of the estimated depth (or upper bound). This particular constraint is shown here for illustrative purposes; other constraints may be chosen in practice. The location and scale parameter values are based on a GEV fit to Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN) data for Berkeley, California, but do not vary materially with the value of the location or scale parameters, as expected since the shape parameter controls the tail behavior.

Bias caused by the use of models of the real world and sensitivity to choices made in the numerical modeling processing are much more difficult to characterize. However, sensitivity across an ensemble of models can be assessed, as is done in model intercomparison projects.

Although this report offers suggestions for possible statistical approaches to achieve the goals of AEP-based PMP estimation and associated uncertainty, the committee envisions that statisticians will be integrally involved in the discussions of how best to use the model output to obtain an official PMP estimate.

MODEL EVALUATION PROJECT

Recommendation 5-12: NOAA should embark on a Model Evaluation Project to assess model skill, identify strengths and limitations relevant to PMP estimation in current and future climate states, and achieve fitness for purpose, which is necessary for community confidence in models for estimating PMP.

The committee recommends that NOAA facilitate a rigorous MEP. The MEP represents an appraisal effort during which NOAA and the broader scientific/operations communities determine when model-based methods are deemed sufficiently good for estimating PMP and thus suitable for transitioning to a model-based approach to PMP estimation. The MEP aims to assess model skill, identify limitations of and methods for improving storm resolving models, demonstrate scientifically supported methods for quantifying impacts of climate change on PMP-type storms, and ultimately achieve fitness for purpose. The MEP will likely take the form of an iterative process that occurs between near-term enhancements (expected within the next 6 years) and the long-term effort (expected within 10 to 15 years). The MEP is also expected to occur between future updates to PMP estimates.

The committee recommends that NOAA structure the MEP as a series of simulation categories that successively build toward the long-term goal of using model simulations to estimate PMP. These simulations are described here and summarized in Table 5-1. The first type of model simulations recommended is event-based reconstructions of historical PMP-magnitude storms. Evaluation of simulation output should focus on storm and precipitation characteristics, such as system size, propagation speed and direction, spatial structure and temporal distribution of precipitation, and event total precipitation. Additional model evaluation should emphasize relevant physical processes associated with the simulated storms, such as generation mechanism, moisture source(s), orographic forcing, and microphysics, among others.

Precipitation data used for comparison with event-based simulations will come principally from the enhanced storm catalog data used for near-term PMP estimation. The temporal and spatial scales of these observations mesh with the scales needed for comparison with model-based reconstructions of precipitation for PMP-magnitude storms. As noted in the Storm Catalog Data section above, high-resolution precipitation fields (approximately 1 km spatial scale and 15-minute time scale) will be constructed for the NEXRAD era and digitized storm catalog data will be available for the pre-radar era. Both can prove useful in comparisons with model simulations. The 3-D polarimetric radar fields are especially important for assessing model performance in accurately representing microphysical processes (Ryzhkov et al., 2020). They can also contribute more broadly to assessments of physical/dynamical processes associated with extreme precipitation. Collectively, these simulations are intended to contribute to storm catalog updates, document model skill, and inform moisture maximization, transposition, and orographic adjustments recommended in the near-term enhancements.

The second type of model simulations recommended includes continuous, historical, kilometer-scale simulations with configurations similar to those recommended

for use in the long-term approach to estimating PMP, only shorter in duration (such as multi-year to decadal), to enable evaluation of seasonal-to-interannual variability simulated by the models. These simulations can be further categorized by simulated domain, including limited-area and global. Emerging examples of continuous, historical, kilometer-scale simulations with limited-area models include work by Rahimi et al. (2022) and Rasmussen et al. (2023). Examples of continuous, historical, kilometer-scale simulations with global domains include work by Stevens et al. (2019) and Taylor et al. (2023). The spatial and temporal resolution of simulation output of these kilometer-scale simulations will enable comparisons of storm and precipitation characteristics, large-scale storm environments (i.e., intensities, frequencies, locations), and quantile-based statistical comparisons of distributions of precipitation at various temporal and spatial aggregations, by storm type as appropriate. The continuous rainfall reanalysis dataset extending from 2000 to 2024 (and beyond; see discussion in Chapter 3 and in the Storm Catalog Data section above) provides precipitation observations for comparison with simulated precipitation fields from the continuous model simulations at comparable grid resolutions.

A natural question to ask when performing these simulations is, when will models be fit-for-purpose to estimate PMP? Required criteria for assessing fitness for purpose include adequately simulating the climatology of extreme events by storm type, including short-duration, high-intensity events (including those over complex terrain) and accurately simulating extreme precipitation events for the correct physical reasons. Beyond model requirements, NOAA should collaborate with stakeholder groups to achieve community acceptance of modeling and analysis plans.

The MEP should be coordinated by NOAA, with participation from the scientific and operational communities. Public dissemination of model results, limitations, improvements, and findings will enhance community knowledge through time. Furthermore, output from successful model simulations used in the MEP may also serve to support community interests beyond use for PMP, and even beyond the climate and hydrology sectors. The community will transition to the long-term estimation approach when models have been deemed fit-for-purpose.

BRIDGING NEAR-TERM AND LONG-TERM STRATEGIES

Transitioning to the long-term model-based approach for PMP estimation poses some risks and challenges. Foremost among the challenges for the 10-year vision are (1) the length of time until models are deemed fit-for-purpose for modeling PMP-magnitude storms and precipitation on climate time scales and (2) the computational requirements for producing the large ensemble kilometer-scale simulations. The first challenge relates to the larger challenge in modeling PMP-magnitude precipitation events in continuous climate simulations, which require skillful simulations of both the large-scale environments that support the PMP storms as well as the PMP-magnitude precipitation. The second challenge includes not only the availability and cost of high-performance computing resources to run a large ensemble of simulations in parallel on different computers, but also the model performance on the computational systems that

determines the simulation throughput and hence the wall clock time needed to complete a multi-decadal simulation covering the historical and future periods. Strategies that may be helpful in addressing these challenges are discussed below.