Modernizing Probable Maximum Precipitation Estimation (2024)

Chapter: 4 Critical Assessment of Current PMP Methods

4

Critical Assessment of Current PMP Methods

OVERVIEW

In 1992, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission requested a National Academies review of methods used to estimate PMP. The assessment concluded that “despite flaws in the PMP estimates developed by the NWS [National Weather Service], there is no compelling argument for making immediate widespread changes… This recommendation is based in part on lack of a clearly better alternative” (NRC, 1994). The assessment recommended critical areas requiring improvement of PMP estimation, notably for short-duration, small-area storms and for extreme storms in mountainous terrain. That committee also recommended pursuing advances in numerical modeling of extreme storms and integration of radar rainfall estimates from the NWS WSR-88D radar network into PMP studies. A final recommendation was for a “major new research initiative to improve scientific understanding of extreme rainfall events” (NRC, 1994). Chapter 3 of this report summarizes the current state of science and recent advances in science and methods, including those developed since the 1994 report.

PMP has provided a rational foundation for designing high-hazard structures and assessing the safety of these structures, but despite recent innovations, the core methods remain grounded in scientific ideas from the early 20th century. The PMP “flaws” identified in NRC (1994) centered on the core methods used for PMP estimation—storm catalogs, storm transposition, moisture maximization, and orographic separation—as well as foundational concepts including that of upper bounds on rainfall. PMP estimation has the appearance of a statistical procedure in which data are collected and an unknown parameter, the upper bound of the distribution, is estimated. This is a reasonable statistical problem, provided that an upper bound exists and a suitable statistical sample is available to estimate the bound. The incomplete nature of storm catalog data does not, however, mesh with notions of conventional statistical samples, and the methods for

converting data to estimates do not align with conventional statistical procedures. The question of bounds on rainfall is at best unsettled.

PMP DEFINITIONS

PMP definitions and the concept of a theoretical upper bound on rainfall have been subject to criticism over the past 60 to 70 years. As noted in NRC (1994), “the dual definition of PMP as a physical upper limit of precipitation and as the collection of procedures used to compute an upper limit has created confusion and has hindered procedural developments.” The concept of a physical upper bound has remained explicit in PMP definitions. PMP is defined in the United States as “theoretically, the greatest depth of precipitation for a given duration that is physically possible over a given size storm area at a particular geographical location at a certain time of year” (AMS, 2022; Hansen et al., 1982). Appendix B provides an expanded treatment of evolving definitions of PMP including those developed by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) (see also Chapter 2 for a summary).

Concept of Zero Risk and Risk-Informed Decision Making

Previous studies (Alexander, 1965; Ben Alaya et al., 2018; Klemeš, 1993; Kunkel et al., 2013b; Papalexiou and Koutsoyiannis, 2006; Salas et al., 2014; Yevjevich, 1968) have criticized standard PMP definitions and PMP estimation because they do not achieve “no risk,” neglect uncertainty, and exclude increases in moisture in a changing climate. Criticisms have focused on risk and the dual nature of the PMP definition and methods used for PMP estimation. Alexander (1965) pointed to PMP definitions that dispense with upper bounds and focus on estimation of annual exceedance probability (AEP). Australian rainfall and runoff studies have included AEP estimates of the PMP since 1987 and note that “assigning an AEP to the PMP is consistent with the concept of operational PMP estimates, which should not be regarded as theoretical upper limits of rainfall, as they may conceivably be exceeded” (Nathan and Weinmann, 2019).

Over the past two decades, major federal dam safety agencies, such as the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), and some states (WA, CA) have moved to utilize Risk-Informed Decision Making (RIDM) for their dam safety programs (FEMA, 2015; FERC, 2016; USACE, 2014; USBR, 2022) rather than rely solely on standards such as PMP and Probable Maximum Flood (PMF). Designs and assessments for nuclear facilities also focus on risk (ANS, 2019). The critical risk input is a flood hazard curve (USACE, 2019a; USBR, 2013; H. Smith et al., 2018; Swain et al., 2006). Schaefer (1994) introduced methods for evaluating AEP of PMP estimates to enhance their utility for RIDM.

Key Observations

A review of current PMP definitions (Hansen et al., 1982; WMO, 1986, 2009), published literature, and assessment of user needs leads to the following key points, with history, details, context, and evolution in Appendix B.

- The original definition of PMP was developed by the NWS in collaboration with USACE and USBR and has changed over time.

- The definitions of PMP center on a physical upper bound on rainfall, which is not supported by observational evidence (see Chapter 3).

- The definition of PMP as an upper bound and methods used to estimate PMP have been subject to confusion. PMP is defined as an upper bound of rainfall, but PMP estimates can be exceeded.

- The definitions of PMP do not fully meet the present needs of the dam and nuclear safety communities, which must consider the uncertainty of the PMP estimate and the connection to probability estimates of extreme rainfall in RIDM for critical facilities.

- The definitions of PMP do not reflect potential changes in extreme rainfall due to climate change.

Conclusion 4-1: The current definitions of PMP are deficient, and a new definition is needed. This definition should acknowledge that PMP (1) is a quantity that is estimated from data, (2) should not be constrained by the assumption of an upper bound, and (3) can change as climate changes.

PMP DATA AND METHODS

Storm Catalog

To estimate PMP for a variety of storm areas and storm durations, a rich collection of major historic storms, that is, a storm catalog, is needed as a starting point (Myers, 1967). The original Miami Conservancy District storm catalog published in 1916 (see Chapter 2) was updated in 1936 and included data from 283 storms in the eastern United States occurring between 1891 and 1933. In addition, the Miami Conservancy District introduced techniques for depth-duration-area analysis that became central components of PMP estimation.

USACE adopted the Miami Conservancy District storm catalog in the 1930s as a cornerstone of its evolving program for design and construction of high-hazard dams. Published in 1945, the initial USACE storm catalog included events from the Miami Conservancy District catalog along with events from regions of the United States not covered by the Miami Conservancy District (USACE, 1945). The USACE storm catalog still serves as a foundation for PMP estimation (England et al., 2020), but the geographic and temporal sampling of U.S. storms has not been consistent during the past eight decades.

Rainfall Observations for Extreme Events

Rainfall data for PMP-magnitude storms include many observations from bucket surveys, especially for short-duration, small-area storms. Development of storm catalogs during the middle decades of the 20th century involved close collaboration between USACE and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Bucket surveys were often carried out by the USGS as a component of special studies of major floods. The July 1942 Smethport, Pennsylvania, storm (Eisenlohr, 1952) and the May 1935 D’Hanis, Texas, storm (Dalrymple, 1939) are notable examples.

The D’Hanis storm defines the United States and world envelope curve of rainfall for time scales around 2 hours, and the resulting Seco Creek Texas flood of 31 May 1935 defines the U.S. and world envelope curve of flood peaks for drainage areas around 300 km2 (Costa, 1987). The extraordinary rainfall observations for the Smethport storm are paired with comparably extreme measurements of discharge and mass wasting from debris flows (Eisenlohr, 1952). Confidence in the rainfall analyses for these and other extreme storms is enhanced by their correspondence with the location, timing, duration, magnitude, and, where determined, the relative rarity (very low AEP) of the resulting flood flows, typically provided by the USGS.

Incomplete sampling of PMP-magnitude events in the USACE storm catalog is due in part to problems of observer bias. USGS flood studies that produced storm catalog events were triggered by observer reports that reflected the perceived societal importance of a particular event weighed against the availability of funding to perform the work. Loss of life was a key factor in close examination of the D’Hanis storm (Dalrymple, 1939); extensive damage to railroad infrastructure was a driver for examination of the Smethport storm. However, many events that resulted in USGS measurements of extreme flood peaks include little or no information on rainfall (Costa, 1987; Crippen and Bue, 1977; Smith et al., 2018). The USGS flood record implies that many PMP-magnitude storms are not included in storm catalog datasets. Another consequence of observer bias is that PMP-magnitude events in sparsely populated regions are less likely to be represented in the USACE storm catalog.

The current USACE storm catalog reflects changing engineering priorities over the course of the federal dam building era (Billington et al., 2005). Rainfall information was most critical during the period of accelerating dam construction from the 1930s and 1940s. When the last major federal dam was completed in the early 1980s, the need and funding for flood studies that enhanced the storm catalog and served PMP estimation had greatly diminished.

Conclusion 4-2: Coverage and completeness of storms in storm catalogs have varied over time and geographically across the United States in ways that are not consistent with conventional statistical samples and therefore preclude conventional characterization of uncertainty in PMP estimates.

Rainfall Estimates from Radar

Following the recommendations of the 1994 NRC study, radar rainfall estimates from the NWS network of WSR-88D radars have become important data sources for storm catalogs and PMP studies (see, e.g., AWA, 2015, 2016, 2019). The 27 June 1995 Rapidan, Virginia, storm is a prominent example of a storm for which radar rainfall estimates control PMP for short durations and small areas (AWA, 2018). Radar rainfall estimates for the storm were constructed using reflectivity measurements with standard Z-R relationships and bias correction using surface rainfall measurements (Smith et al., 1996). Bias correction is an important component of rainfall estimation for the Rapidan storm, as is the case for other PMP-magnitude storms for which reflectivity-only algorithms are used (Baeck and Smith, 1998, Smith et al., 2000, 2005).

Bias remains an important issue for estimating rainfall from PMP-magnitude storms using polarimetric radar observations (Smith et al., 2023, 2024). Rainfall observations from the Community Collaborative Rain Hail & Snow (CoCoRaHS; Reges et al., 2016) network have provided an important source of storm total measurements for computing bias in radar rainfall estimates during the polarimetric era (Martinaitis et al., 2021).

Conclusion 4-3: Radar rainfall estimates have emerged over the past 25 years as a principal source of data for storm catalogs and PMP studies.

Conclusion 4-4: Development of surface rainfall observations from both conventional and nonconventional sources is important for accurate estimation of PMP-magnitude rainfall, especially through assessments of bias in radar rainfall estimates.

Conclusion 4-5: Enhanced information from gauge and observational networks and forensic precipitation-intensity and flood-flow field investigations are critical to accurate storm catalogs. Continued investments and enhancements to NOAA, U.S. Geological Survey, CoCoRaHS and similar gauge and observational networks and post-event field campaigns are necessary to enable more accurate and complete information for understanding and interpreting radar-based observations and model simulations.

Recommendation 5-6 (Chapter 5) is linked to conclusion 4-5.

Although polarimetric measurements from the U.S. radar network have been available for more than a decade, they have not been adequately integrated into estimation of rainfall for storm catalog events (e.g., AWA, 2019). Relative to reflectivity-only methods, there is significant potential for enhancing local corrections of radar rainfall estimates (Chapter 3) using polarimetric measurements (Ryzhkov et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2024). Enhanced polarimetric radar estimation algorithms for PMP-magnitude storms remain a key area of emerging methods to catalog storm data.

Extensive effort has been committed to development of phased array radar technology as a successor to the current generation of weather radars (Zrnic et al., 2007). This emerging technology holds potential for improving estimation of extreme rainfall, especially for short-duration, small-area storms. However, the time scales for development and deployment of phased array radars preclude major impacts on storm catalog development for near-term enhancements to PMP estimation.

Storm Types

Since national generalized PMP estimates were last updated in the 1970s through the 1990s, major advances in scientific understanding of extreme-rain-producing storms have emerged. As discussed in Chapter 3, extreme precipitation can be caused by a wide variety of storm types, including tropical cyclones (TCs), mesoscale convective systems (MCSs), atmospheric rivers (ARs), orographic “upslope” flow, supercell thunderstorms, and even ordinary thunderstorms in some cases. The temporal and spatial distribution of extreme rainfall is closely tied to the type of storm producing it. TCs and ARs may produce large accumulations over multiple days that cover vast areas, but they tend not to produce the most extreme short-term rain accumulations. In contrast, supercell storms can cause extreme short-term rain accumulations, but with relatively small spatial extent.

Storm types were integral to developing and implementing PMP estimation methods, including storm transposition, orographic transposition factors, and moisture maximization. For example, one of the first PMP studies (HMR 3) defined the “Sacramento storm type” (USWB, 1943b) for the Sacramento River, California, watershed using synoptic analysis, cyclone intensity, and 72-hour storm rainfall. Storm typing and storm classification systems played important roles in developing orographic precipitation models for PMP in the western United States such as in California (USWB, 1961), based on synoptic analysis, location and strength of blocking, and evaluation of wind, moisture, and moisture transport (Weaver, 1962). Various storm classification schemes and terms have been used that generally reflect the meteorology and geographic area under consideration. For example, in the Rocky Mountain region, storms were classified as “cyclonic” (with subclassifications as tropical or extratropical with a low-pressure center or front) or “convective” (convex or simple) (Hansen et al., 1988).

Storm types play an important role in determining transposition regions and in setting explicit transposition limits for observed storm rainfall (Hansen et al., 1988; Myers, 1966). Storm types are also used in restricting observed storm rainfalls to certain area sizes or Depth-Area-Duration (DAD) “zones” and storm durations for subsequent maximization and estimation of specific PMP “types.” Many recent statewide PMP studies have used simplified storm types and PMP types in a qualitative and subjective manner to develop PMP estimates (AWA, 2016, 2019).

Storm classification schemes in current use generally reflect concepts from the 1980s and do not reflect recent understanding and knowledge of synoptic and mesoscale meteorology. PMP studies at the time of Hansen (1987) separated storms into “General,” “Local,” “Tropical,” and “Orographic.” General storms are principally linked

to extratropical cyclones, Local storms to thunderstorms, and Tropical storms to TCs. Standard practice in PMP studies over the past several decades has involved separate PMP computations for General, Local, and Tropical storms (e.g., AWA, 2016); these categories mix storm type and PMP type.

Abundant research has shown that storm classification is tricky, especially for PMP-magnitude storms (see Hirschboeck, 1987 for early developments). Similar to prescribing storm transposition regions, dividing storm events into different storm types creates abrupt “boundaries” in PMP storm properties. The remnants of Hurricane Ida (2021) in the northeastern United States produced PMP-magnitude rainfall at time scales less than 4 hours. The storm could be plausibly classified as Tropical, Extratropical, or Local (Smith et al., 2023). Under existing PMP procedures, the choice would have an impact on PMP estimates in candidate transposition areas.

Moreover, “storm types,” as understood meteorologically, and “PMP types,” as used in practice, are not necessarily aligned with one another. For example, in the formulations of Showalter and Solot (1942) and Bernard (1944), the principal storm types identified were (1) quasi-stationary cold fronts, (2) rapidly developing waves along a cold front, (3) major occluded cyclones, (4) TCs, (5) local or frontal thunderstorms, and (6) moist air flow up mountain slopes. In PMP analyses, these storms often been reduced to the categories of “general” storms, with precipitation lasting 24 hours or more and areas exceeding 500 mi2, “local” storms, reflecting intense rainfall occurring over 6 hours or less (see Spatial and Temporal Scales in Chapter 2), and in regions proximate to coastlines, “tropical” storms, reflecting rain from TCs. Some studies also specifically include MCSs and storms that are a hybrid between different storm types. Yet in some state-level PMP studies, the classification of a storm based on meteorological data (such as an MCS) is not used in the PMP estimate for this type.

These classifications also often include implicit, but not explicit, information about seasonality. For example, in some parts of the United States, some storm types are limited to a particular time of year (e.g., TCs in summer and fall, convective storms almost exclusively in the warm season). Therefore, current PMP estimates for “local” storms may only be of concern in one part of the year. On the other hand, some users may require seasonal PMP calculations, for example, for floods that could be caused by rain on snow. The amount of precipitation needed for a dam failure in a rain-on-snow event may be less than if it were rain falling on dry ground.

For many reasons, it makes sense to consider storm type as a component of PMP estimation, and indeed this has been a major consideration in past PMP studies. Although in one sense, infrastructure does not “care” whether the extreme rainfall affecting it came from a TC or MCS, the temporal and spatial distribution of the extreme rainfall will vary depending on the type of storm. Climate change impacts on changes of extreme rainfall may also depend on storm type. Accurate constraints on rainfall accumulations over defined time and space scales will necessarily be aligned with the types of storms that produce the rainfall. Different storm types may also have different levels of suitability or readiness for model-based PMP analyses, with AR events possibly most suitable.

Conclusion 4-6: Knowledge of storm types will remain a core component of PMP estimation at least until PMP can be estimated from long-term model simulations. New scientific knowledge should be incorporated in refining methods for specifying PMP storm types.

Storm Transposition

Storm catalogs and storm transposition have provided the inseparable foundation of PMP estimation from the 1940s to the present. The pairing of the two elements reflects the regionalization philosophy of trading space for time (Box 4-1) in estimating limiting rates of rainfall (Miami Conservancy District, 1916; Myers, 1967; Showalter and Solot, 1942). Given a storm catalog of extreme events, PMP estimation revolves around a storm-by-storm decision on the extent of storm transposition regions (plus “maximization” corrections, as detailed below).

Storm transposition decisions are intended to reflect sound meteorological reasoning, but scientific understanding has often lagged practice. For the Miami Conservancy District design studies, a critical question was whether to transpose a storm that occurred in July 1916 along the eastern margin of the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina to the Miami River basin; rainfall accumulations for the July 1916 storm were markedly larger than other events in the Miami Conservancy District storm catalog. The decision to omit the 1916 storm was based on the assessment that “such storms cannot cross the mountain barrier” (Morgan, 1917). Although reasonable, this decision highlights the limitations of the current subjective approach to storm transposition, which can be overcome with the proposed physics-based modeling approach.

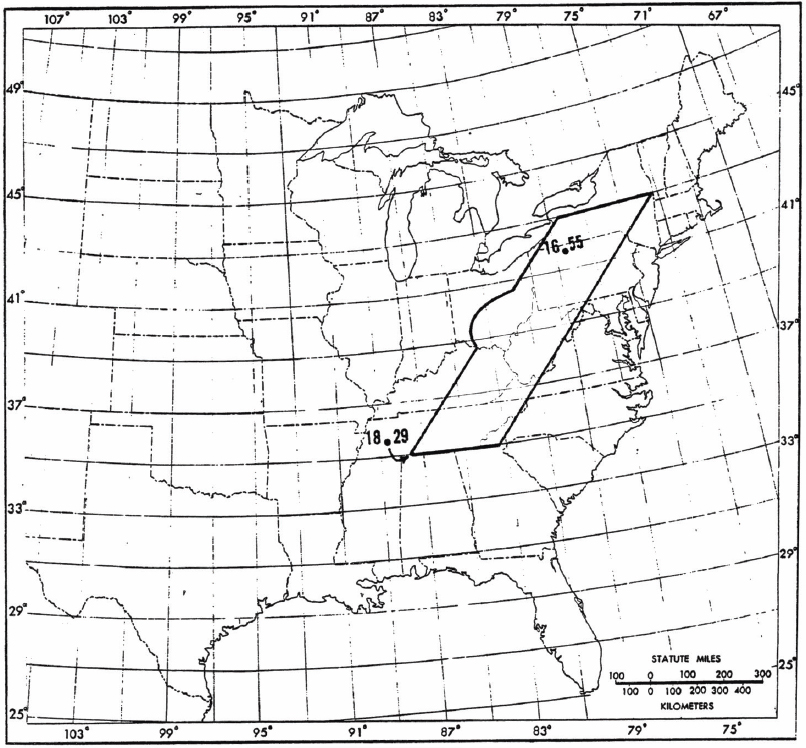

Similar arguments have formed the basis for storm transposition decisions up to the present. The transposition region for the July 1942 Smethport storm in HMR 51 extends for approximately 1,000 miles from northern Alabama into central New York state (Figure 4-1). The eastern boundary of the transposition region is close to the western crest of the Appalachians (Allegheny Front), reflecting the conclusion that such storms cannot cross the mountain barrier. The decision is plausible, but compelling scientific arguments supporting transposition regions for the Smethport storm have not been presented. The supporting arguments used to justify transposition regions are often organized around specified storm types but ultimately rely on the scientific judgment of the meteorologists performing PMP studies (see, e.g., AWA, 2018).

In many regions of the United States, PMP estimates are very sensitive to the transposition region specification, which is based only on a small number of storms (see, e.g., Micovic et al., 2015). For instance, over large portions of the eastern United States, PMP estimates for sub-daily time scales depend strongly on whether the July 1942 Smethport storm is within the transposition region. Transposition decisions for the Smethport storm feature prominently in recent PMP studies for states in the eastern United States (e.g., AWA, 2018). Similar decisions will play an important role in PMP estimates based on near-term enhancements (Chapter 5).

BOX 4-1

Trading Space for Time

The robustness of estimates of the expected frequency of particular extreme rainfall depths depends directly on the number of possible occurrences of such a depth in the data record. If such a depth has occurred several times, a better estimate of its likelihood of occurring in any given future year can be made than if it occurred only once, or not at all. Even if a depth has never been exceeded, it is still possible to estimate the depth’s future frequency by fitting a probability distribution such as a Generalized Extreme Value to the data and essentially inferring how rapidly the frequency of such depths dies off as rainfall intensity increases. The expected quality of such a fit still depends on how many historical events came close to the particular magnitude of interest. In an ideal world, rainfall data would be available at a particular location from hundreds of thousands or even millions of years, and the climate would have not changed at all during that long period of time. Neither of these things is true in the real world.

The idea behind trading space for time is that climates are broadly similar across large geographical areas, and hence a particular rainfall depth or sequence of depths that actually occurred in one location might just as easily have occurred elsewhere in a place with similar climatic conditions. This assumption makes it possible to use information on weather events occurring in a broad region to estimate expected frequencies at individual locations.

In traditional PMP analysis, trading space for time corresponds to storm transposition. The locations where an extreme historical storm might be able to occur are estimated from considerations of climate and geography. Then various adjustment factors are applied to deal with observed or inferred climatic and geographical differences, such as moisture availability.

In regional frequency analysis, commonly used to estimate annual exceedance probabilities of 0.5–0.001 (events with a return period of 2 to 1,000 of years), regionalization is applied on a station-by-station basis rather than on a storm-by-storm basis. In this approach, extreme precipitation records from a set of adjacent stations are pooled, thereby providing a larger sample size for extreme frequency analysis. Often an “index storm” paradigm is used to correct for expected spatial inhomogeneities in extreme rainfall intensity, analogous to the orographic and moisture transposition factors used in traditional PMP analysis. The choice of which nearby stations should be pooled is made semi-objectively, based on subjectively established thresholds for proximity, time series similarity, and other issues.

Other approaches for trading space for time also exist. Newer approaches to precipitation frequency analysis utilize spatial statistical modeling to simultaneously pool data among nearby stations and interpolate to locations between stations, using the statistical properties of the data to infer how much influence distant observations should have on any given local estimate. Alternatively, stochastic storm transposition applies the semi-objective methods of regional frequency analysis to infer possible equivalent locations of the full set of individual historical storms, as opposed to the traditional PMP approach of treating each storm uniquely and subjectively.

SOURCE: HMR 52 (Hansen et al., 1982).

Probabilistic Storm Transposition

Probabilistic concepts of storm transposition have been introduced to account for varying probabilities of storm timing, storm location, and storm characteristics (e.g., storm magnitude, storm pattern/orientation, or a set of meteorological variables associated with a storm) within a transposition region (Foufoula-Georgiou, 1989a). The Stochastic Storm Transposition (SST) approach allows for “uncertainty quantification of extreme rainfall amounts” (not of the uncertainty of the PMP as an “upper limit”), as one can create a relatively large number of storm patterns that could have occurred at a specific location at a specific time of the year and thus compute probabilities of exceedance of extreme rainfall amounts at any desired space and time scale relevant for flood estimation over a basin of interest.

SST has experienced a resurgence of interest in part because of advances in observations, especially from radar (Wright et al., 2014). Advances have been made

in addressing spatial heterogeneities of extreme rainfall (England et al., 2014, Wright and Holman, 2019; Yu et al., 2021). However, even with these new observations and advances, record lengths are not sufficiently long for estimation of PMP-magnitude storms.

As illustrated by Arthur Morgan’s 1917 discussion of transposition across the Blue Ridge, mountainous terrain has introduced troublesome issues for the concept of storm transposition from its inception. These issues are manifested both in the decision-making process for storm transposition regions in and around mountainous terrain (see, e.g., Hansen, 1987) and in the range of “correction factors” (such as moisture maximization discussed below) used to address spatial heterogeneities in the properties of extreme storms. Similar problems arise in other areas of complex terrain, especially regions adjacent to land-water boundaries and urban regions (see, e.g., Perica, 2018).

Conclusion 4-7: Storm transposition is a cornerstone of PMP estimation, but methods used to specify storm transposition regions have relied on subjective meteorological judgment; a solid scientific foundation for storm transposition is not available.

Conclusion 4-8: A model-based approach for developing estimates of PMP (Chapter 5) eliminates the need for subjective storm transposition and associated correction factors that were historically used to address spatial heterogeneities in PMP-magnitude storms across the United States.

Moisture Maximization

The purpose of moisture maximization is to maximize each selected storm to its theoretical upper bound. It involves multiple key assumptions, some of which have not been scientifically validated to date. It also involves subjective judgments that may not be independently reproducible and could at times seem arbitrary. Nevertheless, it is an important step in the conventional PMP estimation paradigm.

Conventional Approach in Estimating PMP

Following the paradigm discussed earlier that P = EqwD, and, assuming that PMP represents a physical upper bound to precipitation, the conventional approach to estimating PMP seeks to estimate that upper bound using observed quantities. Recognizing that an insufficient number of historical storms approach the hypothetical upper bound to permit direct estimation of that upper bound, the conventional approach estimates the maximum value of the components of P individually.

Only certain maximum values can be estimated, however. The duration D is pre-defined by the particular PMP being estimated. Historical observations provide extensive information on the range of possible values of moisture q. The precipitation efficiency E is not measured directly but is known to approach 1 for the heaviest rainstorms and even exceeds 1 for short periods of time through horizontal convergence

of hydrometeors. Doppler radar observations in the modern era provide a means of directly determining the distribution of w, the maximum vertical motion maintained over a period of time D. But historical observations of vertical motion w, or equivalently convergence, were unavailable when conventional PMP methods were developed.

To overcome this deficiency, the conventional approach identifies “PMP-type” storms, those for which Ew is largest for a given D. Because EwD = P/q, and assuming a PMP-type storm can be identified that features the upper bound on combined vertical motion and precipitation efficiency for a given duration (EwD)ub, within that storm we have (EwD)ub = Pobs / qobs. If moisture and dynamics are quasi-independent, Pub = (EwD)ub qub, and therefore PMP = Pub can be estimated from a PMP-type storm as PMP = Pobs qub / qobs.

This approach is explained by Myers (1967) as assuming that extreme events provide “the effective measure of convergence” of the wind field. The storm transposition step translates observed storm rainfall (i.e., the indicator for maximum convergence of the wind field) to the location where a PMP estimate is to be computed. The quantity that is interpolated is interpreted as the “convergence and vertical motion” of the wind field, which is “unmeasured but is indicated by the precipitation.” It is further assumed that a sufficiently large sample of extreme storms has been detected and “at least one of them contained a convergent wind mechanism very near the maximum that nature can be expected to produce in the region.” Overall, this concept leads to an in-place maximization factor (IPMF) in practice:

(1)

where PWStorm,S1,Z1 is calculated by a selected storm representative dew point temperature, at a location (S1) that may represent the main source of moisture controlling the storm event, and from the storm elevation center elevation (Z1) to the top of atmosphere (i.e., 30,000 ft elevation in the conventional calculation). Similarly, PWMax,S1,Z1 is calculated by the historically maximum dew point climatology at the same location and elevation. In practice, an upper bound of 1.5 is imposed to avoid over-adjustment; however, no clear justification has been provided to support this specific value of upper bound (see DeNeale et al., 2021 for further discussion).

Both practical and theoretical assumptions are embedded within this approach. The practical assumptions are that both the moisture available to a given PMP-type storm and the upper bound on moisture can be estimated sufficiently accurately. The theoretical assumption is that the dynamics of the strongest storms, encapsulated in EwD, are independent of the thermodynamics q.

Moisture, Water Vapor, and Dew Point

In principle, the storm moisture should be the integrated water vapor within the saturated updraft of the storm averaged over the storm duration. In practice, direct obser-

vations of moisture within a storm are usually unavailable. If the storm is convective in nature—a class that includes ordinary thunderstorms, supercells, MCSs, and TCs—the updraft air originates from low levels in the atmosphere, and surface observations of dew point temperature in the inflow region of the storm can be used to characterize the moisture profile within the storm.

However, the process of estimating a representative dew point for an extreme storm involves important subjective judgments. As a result, different analysts may come up with different dew point values and arrive at different conclusions, which limits the reproducibility and credibility of the conventional PMP estimates. To estimate a representative dew point, a PMP analyst needs to review the storm track manually, identify stations with available dew point observations along or upwind of the storm track, and infer which upstream air will reach the storm location right before the occurrence of the storm event. Storms occurring near coastlines may have no upwind dew point observations available, in which case analysts must assume that atmospheric dew point temperatures can be estimated from nearby sea surface temperatures.

In larger-scale or orographically driven systems, such as extratropical cyclones and ARs, ascending air can cover horizontal distances of tens or hundreds of kilometers in its journey from the lower to the upper troposphere, with much or all of its ascent over cooler low-level air. For such storms, surface dew point or sea surface temperature may be grossly unrepresentative of moisture content in any given ascending column. In such circumstances, the upstream precipitable water (i.e., the total column water vapor) is a better measure of moisture within a storm system. However, vertically integrated water vapor measurements are rare for historical storms, so analysts must rely on computer-generated analyses of storm environments. Such analyses are inherently less accurate for storms prior to the satellite era (which began around 1979) and considerably less accurate prior to the rawinsonde network era (starting around 1948), rendering moisture maximization of older storms much less accurate than for newer storms.

The upper bound on the moisture that could hypothetically be available to a given storm also involves some arbitrariness and subjectivity. Different types of storms may only happen in particular seasons at particular locations, and the maximum possible moisture available to a storm thus depends on the time of year in which such a storm can occur. In the current practice, a 2-week window toward the warmer months is used to determine the applicable dew point climatology for estimating maximum possible moisture for a given storm (e.g., using the April 30 maximum dew point to maximize an April 16 storm). Depending on the type of available data, a 100-year return period dew point or a two standard deviation sea surface temperature may be used, although it is not obvious why different parts of the probability distribution should be used for dew point or sea surface temperature. Neither approach represents a theoretical or practical upper bound on moisture availability. In addition, no authoritative effort has been made to create and update dew point or precipitable water climatology maps to support PMP analysis (DeNeale et al., 2021).

Conclusion 4-9: The current process of estimating a representative dew point for an extreme storm involves subjective judgments and is difficult to independently reproduce.

Conclusion 4-10: The upper bound on the moisture that could hypothetically be available to a given storm involves arbitrariness and subjectivity. Verifiable dew point or precipitable water climatologies, such as from modern reanalyses, would improve consistency and reduce, but not eliminate, subjectivity.

Assumptions of Independence

One way to test the assumption of independence of dynamical and thermodynamic effects is by observed or simulated behavior of intense storms. Such studies have failed to find a linear relationship between total precipitation and available moisture. Observations of short-duration, small-area PMP storms such as the 1947 Holt, Missouri, storm have found surges of dynamical intensity occurring at the same time as increases of inflow moisture amounts (Lott, 1954). Studies using numerical simulations of intense storms with altered atmospheric moisture typically find nonlinear relationships between moisture and overall precipitation (Abbs, 1999; Chen and Bradley, 2007; Papalexiou and Koutsoyiannis, 2006; Rastogi et al., 2017; Yang and Smith, 2018; Zhao et al., 1997).

Whether independence within individual storms is absolutely necessary is not clear. A weaker constraint would require independence in a statistical sense, that is, that the population of high-end storm dynamics be uncorrelated with the population of high-end available storm moisture. For example, extreme precipitation from a supercell thunderstorm or MCS is maximized when the outflow boundary or gust front is stationary, which requires just the right amount of cold pool generation through evaporation and melting of falling rain, snow, and hail. A slight change in moisture could alter the production of cold air, causing the gust front to advance or retreat and preventing the most intense precipitation from being concentrated over a small area.

Toward that end, recent studies of statistical Clausius-Clapeyron (C-C) scaling of extreme precipitation using dew point temperature are relevant. Observations of apparent C-C scaling tend to show annual maximum precipitation exhibiting scaling greater than Clausius-Clapeyron at sub-daily time scales but not daily or above (Ali et al., 2021; Guerriero et al., 2018; Wasko et al., 2018). Pérez Bello et al. (2021) compared observed annual extremes to seasonal mean dew points (which are more closely related to climate scaling than apparent scaling) and found a scaling of about 12%/°C. Modeling studies (Lenderink et al., 2021; Visser et al., 2021) find 10−14%/°C scaling at hourly accumulations, less at longer accumulations.

In summary, moisture maximization has practical challenges, both for conventional maximization of historical events and computer simulations that attempt moisture maximization of historical events. The overall concept of moisture maximization may approximately hold for long-duration precipitation extremes but underestimates the interaction between moisture and dynamics in short-duration extremes. Recent research suggests that for 1-hour extremes, rainfall totals increase by 1.5−2.0 times the increase in moisture.

Conclusion 4-11: The assumption of independence of dynamical and thermodynamical effects used in past studies is contradicted by research that suggests an intensification of convergence with an increase in moisture.

Transposition Factors

Following in-place moisture maximization, additional multiplicative correction factors are used to adjust a moisture-maximized storm from its original location to a targeted new location. These factors are also based on the concept that the relative change of maximum available moisture can be used to linearly adjust PMP. They also involve strong assumptions and subjective judgments, similar to the limitations encountered during in-place moisture maximization.

Moisture Transposition

When transposing a moisture-maximized storm from one location (X1) to another (X2), two types of adjustment factors are used: one to modify moisture availability at the new location, and another to account for the influence of terrain and orography.

Moisture transposition adjustment accounts for the differences in the maximum available moisture (i.e., PWMax); in conventional practice, this is determined by dew point climatology. In particular, a moisture transposition factor (MTF) is used:

(2)

where PWMax,S2,Z2 is calculated by the maximum dew point climatology at the transposed moisture source location (S2), and from the transposed storm elevation center elevation (Z2) to the top of atmosphere (i.e., 30,000 ft elevation in the conventional calculation). The MTF is reduced (less than one) when transposing a storm to a location with a lower dew point climatology or a higher storm center elevation, and vice versa. Similar to Equation 1, the concept is based on the adjustment of the maximum available moisture based on dew point climatology. Therefore, the same limitations, such as the quality of dew point climatology maps and the determination of frequency levels, also apply.

While MTF accounts for differences in the maximum available moisture, it does not address other modifications resulting from terrain effects. Therefore, terrain and orography adjustments are needed. Broadly speaking, as air masses encounter mountains or elevated regions, they are forced to rise, leading to adiabatic cooling. This cooling can enhance condensation and precipitation on the windward side of the mountains, resulting in higher rainfall amounts than would be expected in a flat, homogeneous region. Therefore, when transposing a storm from flat terrain to a mountainous terrain, an orographic enhancement factor will be needed. If a major barrier exists along the storm track, the lower elevation moisture will not be able to cross the barrier and reach a targeted destination. In such a case, a barrier reduction factor will be needed.

Barrier Adjustment

In the conventional practice, when a barrier exists along the transposed storm track, a Barrier Adjustment Factor (BAF) is used to allow only a portion of the moisture to reach the transposed storm center.

(3)

where PWMax,S2,Z3 is still calculated by the historically maximum dew point climatology at the transposed moisture source location (S2), but instead of using the transposed storm center elevation, it calculates PW from the average barrier elevation (Z3) to the top of atmosphere, and hence reduces the amount of PW (precipitable water).

One issue that BAF does not consider is whether physical barriers in the original storm track caused moisture depletion, resulting in less total PW downwind of the barrier (DeNeale et al., 2021). Additionally, one may question whether it is reasonable to simplify the complex barrier into an average barrier elevation in the calculation. A larger issue is the assumption of an ideal and static distribution of water vapor as air crosses topography, which is unlikely the case during real moisture transport. Therefore, BAF is an idealized approximation of orographic effects.

Orographic Enhancement

Orographic enhancement of extreme precipitation is a more challenging issue to address. Conventionally, a storm separation method (SSM), proposed in HMR55A (Hansen et al., 1988), has been used for orographic enhancement. SSM is based on the idea of estimating the amount of precipitation resulting only from dynamical ascent (i.e., convergence precipitation), and then increasing the values of the convergence rainfall to account for the orographic enhancement over the region, following empirically based methods to determine the adjustment factors. The process is complicated, and the rationale for the individual steps are not clearly documented. The complexity of SSM has prevented its use in recent PMP studies, and an alternative to SSM has not been developed (DeNeale et al., 2021).

Recent PMP studies have used the rainfall depth ratio from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Atlas 14 precipitation frequency product as an orographic adjustment factor. Specifically, an orographic transposition factor (OTF) was proposed (AWA, 2013):

(4)

where PAtlas14,100-year,X1 represents the 100-year rainfall depth at location X1 from the NOAA Atlas 14, and PAtlas14,100-year,X2 is the value at location X2.

The large geographic variation in NOAA Atlas 14 precipitation estimates over and around complex terrain makes the approach an appealing option for specifying OTFs, especially when transposing a storm from flat terrain to complex terrain. The question is whether the simple depth ratio in Equation 4 can indeed provide an accurate representation of the orographic enhancement. There are practical questions concerning the selection of 100-year return level as an index for orographic enhancement; other return levels may lead to different OTFs.

Additionally, a transposition factor of this kind incorporates a range of information unrelated to orography. When deriving an adjustment factor using NOAA Atlas 14 for two locations with similar orographic features, the adjustment factor could be very different. An OTF computed in this way includes other factors such as moisture availability, the availability and quality of rain gauge data for frequency analysis, the selection of probability density functions, goodness-of-fit, and more. Although the intent of SSM was to estimate the sole influence of orography based on the best understanding of rainfall processes, OTF in the current form is an unverified approximation to the complicated SSM process (see DeNeale et al., 2021 for further discussion).

Recent PMP studies have expanded the OTF to a geographic transposition factor (GTF), in which this new factor can replace parts of the MTF functions, eliminate the use of BAF, and be applied everywhere even when the orographic adjustment is not needed. This practice also received some critical attention and remains unverified. There has not been a rigorous and independently validated study to evaluate the strengths and limitations of this approach.

In summary, multiple transposition factors are used in PMP studies to adjust the moisture-maximized storms to their new locations. Although in the long term the committee believes that these processes can be replaced by more justifiable numerical modeling approaches (discussed in the following chapter), in the short term a need to enhance these legacy methods remains.

Conclusion 4-12: Among the factors involved in storm transposition, the most significant challenge lies in addressing the orographic effect. There has not been a reproducible and scientifically justified method to handle all aspects of orographic adjustment. Although the storm separation method (SSM) remains a standard approach to estimate orographic enhancement, it is difficult to replicate results based on SSM analyses.

Conclusion 4-13: Although rainfall frequency products may offer useful information to quantify the influence of orography on rainfall extremes, orographic transposition factors (OTFs) have not been rigorously and independently assessed to document the strengths and limitations of this approach. In particular, expansion of OTF to regions that do not require orography adjustment should be discouraged.

Precipitation Frequency Analysis

As discussed previously, NOAA precipitation frequency products (Box 2-1) play a contributing role in PMP estimation by providing orography-related information for conventional SSM and OTF methods (AWA, 2018; Hansen, 1987). The underlying assumption is that rainfall frequency analyses for a long return interval (typically 100 years) can reflect spatial heterogeneities of PMP rainfall. This assumption has not been adequately examined for many regions of the United States and is especially problematic for sub-daily time scales, for which the density of rain gauges is extremely sparse, even for densely populated regions of the eastern United States. There are settings in which 100-year rainfall frequency fields are markedly different from PMP fields; the Upper Ohio Valley, for example, is a local minimum in sub-daily 100-year rainfall and a local maximum in PMP estimates.

In mountainous regions, the density of sub-daily rain gauges is typically sparse and in many settings the precipitation at low elevations is sampled more completely than at higher elevations. To address spatial heterogeneities in complex terrain, rainfall frequency analysis procedures have integrated mean rainfall fields derived from PRISM (Daly et al., 2008). These likely improve precipitation frequency results, but the relationships between mean rainfall from PRISM, 100-year rainfall from NOAA precipitation frequency products, and PMP estimates have not been adequately examined.

Conclusion 4-14: The sparsity of sub-daily rain gauges limits the utility of NOAA precipitation frequency products for implementing correction factors.

Comparisons between NOAA precipitation frequency products and PMP estimates have also been used to provide assessments of potential inconsistencies in PMP estimates. For sub-daily time scales, the sparse distribution of rain gauges and the poor sampling of PMP-magnitude rainfall (see Chapter 2) results in large uncertainties in precipitation frequency estimates for long return intervals. Nonstationarities in subdaily precipitation extremes over the historical record are also a serious challenge for Precipitation Frequency Analysis (PFA) (DeGaetano and Tran, 2022; Smith et al., 2024), introducing additional uncertainty in rainfall frequency estimates for low AEPs.

Conclusion 4-15: Gauge-based precipitation frequency products for sub-daily time scales are of limited utility for comparison with PMP estimates. Extreme value analyses based on sub-daily rain gauge data are not suitable for assessing return intervals of PMP estimates.

NOAA Atlas 14 precipitation frequency products span a limited range of AEPs, with the smallest being 0.001 (see Box 2-1). NOAA states that PMP is used for assessment of critical infrastructure and that NOAA Atlas 14 frequency estimates are for low-hazard and minor structures, stating that estimates are “not intended for use beyond 1000-year average recurrence interval, or 1/1000 AEP” (NWS, 2020). NOAA does not provide precipitation frequency products (for any duration) with AEPs less than 0.001 or depth-area relations (ACWI, 2018), both of which are needed for RIDM.

Since the late 1990s, regional PFA (e.g., Coles, 2001; Hosking and Wallis, 1997) has been performed for dam safety RIDM applications (see summaries in England et al., 2011, 2023). These studies utilize the statistical advances described in Chapter 3 and provide watershed-average extreme precipitation distributions with AEPs usually ranging from 10-4 to 10-8 for individual dams. Durations are typically 24 hours to 72 hours, with data from precipitation gauges and storm catalogs. Studies have been conducted for USBR, USACE, TVA, and others to assess the safety of the largest dams in the United States (e.g., Friant and Shasta Dams in California) using RIDM, as well as for states (see Figure 2-2 in Chapter 2). While concerns exist about the ability to derive very low AEP depth estimates solely from limited historic observations, and the methodological limitations that regional frequency analysis cannot address nonstationarity or climate change, these estimates are used in designing risk reduction measures and modifications of high-hazard dams (e.g., USBR, 2013). In these settings, PMP has been used as an upper bound to precipitation frequency relationships.

Data and methods used in these regional precipitation frequency studies have been used to provide approximate estimates of the AEP of PMP, typically for large watersheds in the western United States, for integration with RIDM (Box 4-2). Schaefer (1994) notes that these studies were intended to provide magnitude-frequency relationships of extreme storm rainfall and not specifically targeted to estimate the AEP of the PMP. However, results give insights into the range of AEP estimates for PMP at various watersheds and across broad regions, with recognition of the uncertainty of the estimates.

Conclusion 4-16: A comprehensive study of methods to estimate the AEP of PMP has not been performed. There are limited locations where AEP estimates of PMP have been made.

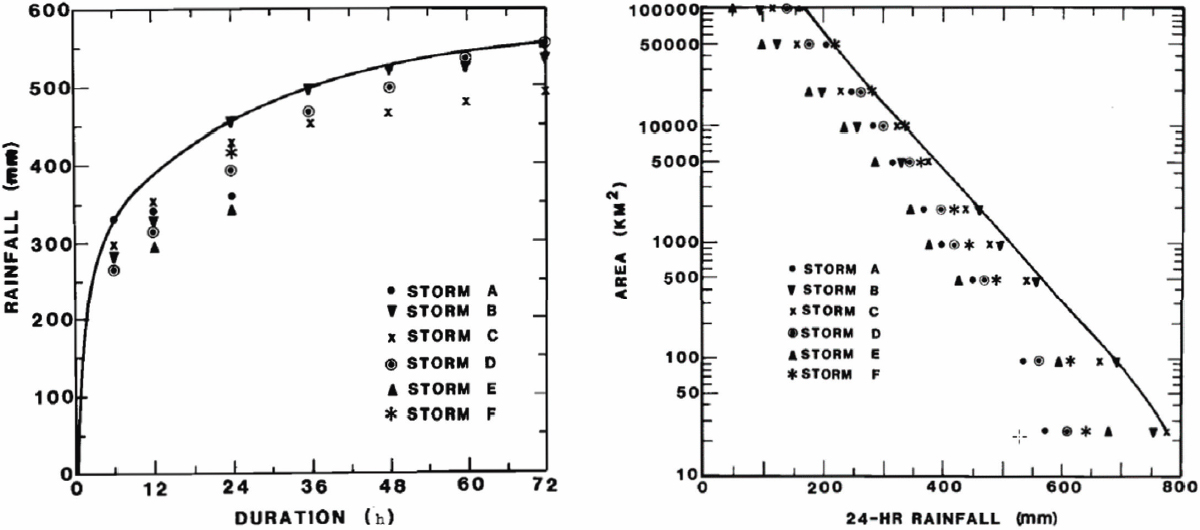

Envelopment

Envelopment is a process to create the final PMP curves that encapsulate the largest values from all moisture-maximized storms (e.g., WMO, 1986). In particular, despite utilizing transposition techniques to increase the number of storms, there can still be gaps in areas and durations that need to be estimated during the envelopment process (Figure 4-4).

Envelopment is a key PMP concept that follows storm maximization and transposition. Maximization and transposition of major storms typically set the very lowest value of PMP at each grid point (Ho and Riedel, 1980). Envelopment establishes consistency throughout the study area and alleviates anomalies (Cudworth, 1989), so that the effects of using a limited number of storms can be reduced. Envelopment is typically performed for various area sizes and within various durations, to account for regional effects, and seasonal estimates (Corrigan et al., 1999; Ho and Riedel, 1980; WMO, 1986), so that PMP estimates are consistent throughout the region. Envelopment is typically applied to all basin-specific estimates as well as generalized PMP estimates. The basic envelopment process is to create maps of maximized and transposed PMP estimates from the largest (controlling) storms at pre-determined grid points (for regions) or the watershed

BOX 4-2

Annual Exceedance Probability of PMP

Limited estimates of the Annual Exceedance Probability (AEP) of PMP have been made using regional precipitation frequency analysis (advances described in Chapter 3) for 24- to 72-hour durations and various watershed scales (hundreds to several thousand square miles) in the United States. The AEP of PMP is not a constant value and depends on the following main factors:

- Storm duration and type,

- Storm and watershed scale, and

- Location.

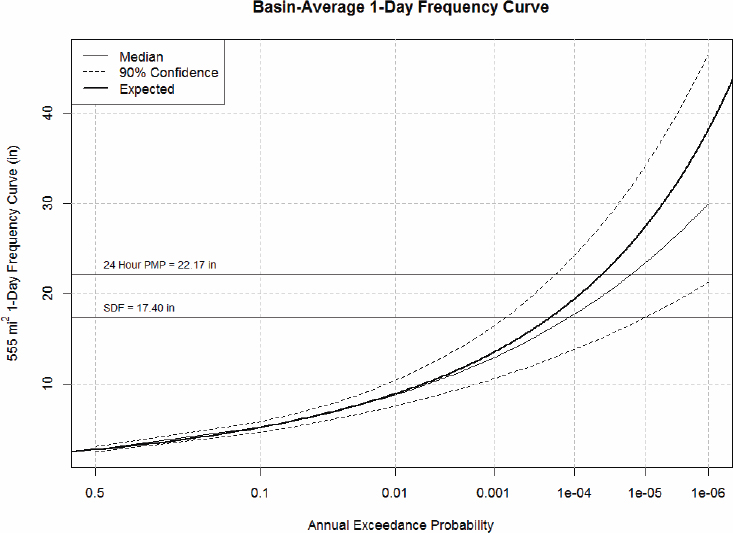

For atmospheric rivers and mid-latitude cyclones examined in some western U.S. watersheds, AEP of PMP estimates range from 10-4 to 10-7. A representative example for one watershed is shown in Figure 4-2. It is important to quantify the uncertainty in the AEP estimates, which can span three orders of magnitude at a location; point estimates are typically used.

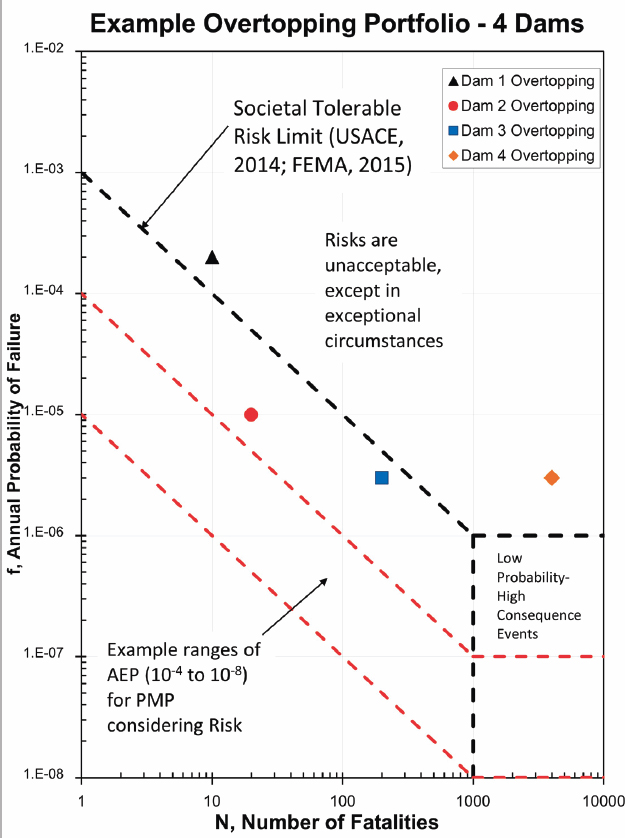

Federal guidelines for dam safety risk management (FEMA, 2015) are useful in considering the range of AEPs of PMP that could meet Risk-Informed Decision Making (RIDM) guidelines as shown in Figure 4-3. The guidelines depict a relationship between probability of failure and consequences. For overtopping failure, the dominant factor is the flood hazard curve (magnitude and probability). Four example dams, representing potential failure from overtopping, illustrate that no unique flood hazard AEP would meet the guidelines. Likewise, the AEP of PMP needed to meet the guidelines is variable and depends on consequences.

centroid (for basin-specific estimates). At each grid point, smooth enveloping curves are estimated for each duration and for each area size (e.g., Figure 4-4). PMP maps are developed for each duration and area based on the envelope curves, and a final spatial smoothing step is performed to connect estimates at all locations. The PMP maps in HMR 51 (Schreiner and Riedel, 1978) are one example of this process.

Envelopment History and Applications

Envelopment methods and variables chosen for envelopment have changed over time. Envelopment was implemented in the first basin-specific PMP studies in the United States, HMRs 1 through 3. Envelopment was used in the first generalized PMP estimates for the eastern United States (HMR 23) and in subsequent generalized

NOTE: (SDF – Spillway Design Flood precipitation depth used in the 1946 design). The AEP of PMP for this watershed spans nearly three orders of magnitude, with a mean (expected) value of about 4.7×10–5.

SOURCE: H. Smith et al. (2018).

PMP estimates for this region (HMRs 23, 33, 51, 53). In California (HMR 36) and the Pacific Northwest (HMR 43), generalized PMP estimates were developed by estimating convergence and orographic PMP separately with an orographic precipitation model. Envelopment was applied to precipitation/moisture ratios for convergence PMP. In the Southwest (HMR 49), envelopment was applied to moisture-maximized storms in regions with minimal orographic influence. Envelopment of convergence PMP estimates (index map values) was performed for generalized estimates in the Rocky Mountain region (HMR 55A) and revised studies in the Pacific Northwest (HMR 57) and California (HMR 59). In each of the generalized HMRs, envelopment was also used in developing 12-hour maximum persisting dew points.

The use of envelopment in statewide and regional PMP studies performed by consultants has varied, depending on the study. Envelopment of PMP estimates was

NOTE: Risk estimates of dams 1 and 4 exceed the guidelines; risk estimates for dams 2 and 3 are less than the guidelines. The red lines represent conceptual PMP AEPs that could be considered consistent with this risk guideline.

SOURCE: Adapted from FEMA (2015).

NOTES: The left image illustrates depth-duration envelopment of transposed and maximized PMP estimates from 6 to 72 hours for a 2,000 km2 storm area. The right image shows depth-area envelopment of transposed and maximized 24-hour estimates across storm areas ranging from 20 to 100,000 km2.

SOURCE: WMO (1986).

performed in the Wisconsin-Michigan (EPRI, 1993), Nebraska, and Ohio statewide PMP studies, generally applied to depth-area curves by duration, similar to envelopment in HMR 51. Starting with the Arizona PMP study (AWA, 2013) and subsequent studies (e.g., VA, TX, CO-NM, PA, TVA), fixed geographic transposition zones were used. Storms were transposed to specific transposition zones, and envelopment was not performed across transposition zones, which can result in sharp discontinuities of PMP estimates in adjacent locations. Such discontinuities can be clearly seen in PMP maps from various statewide studies, such as the Virgina 72-hour, 100-mi2 general storm map; the Colorado-New Mexico 24-hour 10-mi2 general storm map, and the Texas 24-hour 100-mi2 tropical storm map. Thus, transposing storm center locations without envelopment can result in artificial spatial gradients in PMP. Depth-duration envelopment and depth-area envelopment of PMP estimates were not performed in these studies, leading to lower estimates in some locations. The review board for the TVA PMP study recommended improvements and investigation of new methods, including using larger area storm centers, rather than single grid points (TVA, 2018); this would improve implicit transposition and envelopment.

Critical Assessment

Envelopment has been widely used in basin-specific and generalized PMP estimates from the 1940s through the early 2000s. Envelopment methods were largely conceived in the 1940s to smooth variations in sparse spatial and temporal storm rainfall data and subsequent PMP estimates. Envelopment concepts and methods are not sufficiently grounded in the physics of storm rainfall or in statistical methods. The concept and implementation have remained essentially static since the WMO (1973) definition (which was retained in subsequent WMO PMP manuals), other than minor variations in choice of variables for envelopment. This neglects advances in statistics (regionalization, scaling relations), storm mechanisms, storm types, transposition, and other physical insights on storm properties in space and time over a region. Envelopment has not been performed in recent statewide and regional studies; this generally leads to lower numbers and distinct discontinuities across states and state boundaries of studies. Envelopment procedures are not formalized across spatial scales or time scales in statewide or regional PMP studies. Ad-hoc grid-based procedures do not envelope and smooth across various transposition zones.

Conclusion 4-17: Although envelopment methods are widely used, their implementation has not been formalized and the procedures are not compatible with statistical approaches to PMP.

Uncertainty/Sensitivity Analysis

Current PMP practice begins with an assumption that the distribution of precipitation has an upper bound. This is the quantity (i.e., statistical parameter) that a PMP procedure seeks to estimate.

“Statistical” uncertainty (i.e., sampling uncertainty) is the familiar type of uncertainty associated with a statistical sample. Among other things, it can be used to produce uncertainty intervals (e.g., confidence or credible) for a population parameter or function of such parameters. A fundamental characteristic of sampling uncertainty is that as sample size increases, the uncertainty decreases, provided data are available that can inform the quantity of interest.

PMP estimation has the appearance of a statistical procedure, like the one Horton envisioned, in which data (precipitation measurements from historical storms) are collected and an unknown parameter, the upper bound of the distribution, is estimated. One can conceivably formulate the estimation of PMP as a well-defined statistical problem, provided an upper bound exists and a suitable statistical sample is available to estimate the bound. However, it is difficult to reconcile PMP practice (maximizing possible precipitation from an incomplete catalog of storms) with conventional statistical procedures for converting a statistical sample to an estimate for a quantity of interest. The number of storms, or even the number of observed/recorded years, is unclear, and the relevant storms are not used as a statistical sample. PMP is estimated from a single “controlling” transposed storm and subject to maximization and orographic adjustment, which does not fit within standard statistical estimation approaches. Although it would seem that over time the information about the PMP parameter (upper bound) would increase (the data record is more complete), how to use this information to narrow an uncertainty interval is unclear. (Of course, no uncertainty interval currently exists to improve upon.) Moreover, the practitioner community has not viewed or treated PMP as a statistical procedure, but rather a computation involving subjective choices about storm transposition, moisture maximization, and transposition factors. PMP practice has distinguished theoretical PMP from operational PMP, which consists of the steps used to compute PMP. One form of this approach is to treat operational PMP as the definition of PMP. For conventional PMP estimation, the distinction is not significant. But defining PMP by the steps used to compute it precludes statistical uncertainty estimation, one of the central tasks that the committee was asked to address.

Conclusion 4-18: Existing PMP methods do not characterize uncertainty in the standard statistical sense of sampling uncertainty and are not structured such that standard statistical techniques could be applied to estimate sampling uncertainty.

Other useful notions can provide insight about uncertainty, broadly defined.

Sensitivity

Because current PMP estimation requires various expert judgment-based decisions, the sensitivity of the PMP estimate to these decisions can be assessed. Rather than calculating PMP from single values of input quantities determining moisture maximization, transposition, and other factors provided by experts, one could instead conduct Monte Carlo experiments where one repeatedly draws from a distribution of possible values for those key quantities (e.g., Micovic et al., 2015). However, the width of a

PMP interval obtained by a Monte Carlo experiment is not determined by the size of a sample, but only by an expert’s a priori notion of uncertainty assigned to each unknown input component. Furthermore, given that PMP is focused on very unlikely events, the Monte Carlo results could be sensitive to the tails of the expert’s distribution and to how the resulting distribution is used; for example, it is not clear how using a 95 percent interval when considering an upper bound could be justified. These (“prior”) distributions are usually specified based largely on expert judgment but potentially informed, albeit perhaps qualitatively, by data. Thus, the uncertainty reflects the uncertainty in the expert judgment and decreases only when the variability encoded in the expert’s distribution(s) decreases. Such Monte Carlo experiments can provide useful information about the sensitivity of the PMP estimate to the various input values and settings/configurations. However, the danger of such experiments that formally integrate over expert uncertainty (as opposed to, say, simple sensitivity analyses that vary an input parameter and report how the answer changes) is that consumers of such results will interpret them as reflecting standard statistical uncertainty. If all experts were to agree on the treatment of every storm, the Monte Carlo experiment would show zero sensitivity, yet uncertainty from the small sample of extreme storms would remain.

Stochastic storm transposition approaches can also produce uncertainty intervals (e.g. Foufoula-Georgiou, 1989a; Wright et al., 2013, 2020). The spread in these intervals results from drawing events and their characteristics from input distributions (e.g., distributions reflecting how far a storm might be transposed and in what direction). These input distributions are also based on expert judgment and therefore the resulting uncertainty can also be characterized as Monte Carlo uncertainty assessment. Again, the uncertainty interval does not have the standard statistical interpretation of statistical coverage.

Agreement

A second notion is agreement. Riedel and Schreiner (1980) compared PMP estimates over a range of spatial and temporal scales to the largest observed rainfall in the United States, focusing on events for which observed rainfall accumulations are greater than 50 percent of PMP estimates. Their results point to poor sampling of extreme storms in some regions of the United States (especially short-duration, small-area storms in the western United States). Riedel and Schreiner (1980) also compare PMP estimates to 100-year point rainfall accumulations, noting the inherent differences in the two products. Comparison with precipitation frequency estimates also points to sampling issues for short-duration rainfall extremes in portions of the United States. Comparisons of PMP estimates with observed rainfall and with rainfall frequency results in Riedel and Schreiner (1980) are not intended to provide direct assessments of agreement but to provide guidance on regions that are most likely to have significant errors.

Like PMP, PFA aims to characterize extreme precipitation events. Although there could be some overlap in the data that the two approaches use, PMP and PFA have been developed largely independently. It is difficult to reconcile PFA with current PMP practice, because PMP assumes an upper bound and PFA typically concludes that pre-

cipitation is unbounded and heavy-tailed. However, the notion of sample in PFA is well defined, and traditional notions of statistical uncertainty are readily available, although uncertainty intervals for PMP magnitudes are often too large to be useful for decision making. Despite their differences, a PMP estimate and a PFA characterization can be compared, and agencies performing RIDM are already doing this.

Synthesis of Critical Assessments of Current Methods

Current methods for PMP estimation are grounded in scientific concepts that are more than 70 years old and do not adequately reflect advances in scientific understanding of extreme rainfall that are detailed in Chapter 3. Recent PMP studies have integrated radar rainfall estimates into development of storm catalog datasets, but continued enhancements to rainfall data, especially through the full utilization of polarimetric radar observations, are needed. Historical storm catalogs have inherent limitations for PMP estimation because of the incomplete sampling of PMP-magnitude storms.

The principal components of PMP estimation—storm transposition, moisture maximization, application of transposition factors and envelopment—have weak scientific grounding and rely heavily on subjective judgment by PMP practitioners. The subjective nature of PMP estimation methods and the incomplete sample of PMP events in storm catalogs preclude assessment of statistical uncertainty in PMP estimates. The effects of climate change on extreme rainfall have been broadly recognized (Chapter 3), but procedures for integrating the effects of climate change on PMP have not been adequately assessed or implemented.

Standard methods for PMP estimation do not have a solid scientific grounding, but better integration of scientific understanding of extreme rainfall into the implementation of PMP procedures holds some potential for enhancing PMP estimates. Enhanced understanding of PMP-magnitude storms, especially through model-based reconstructions (e.g., Mahoney et al., 2022; see also discussion in Chapter 5), can provide a better foundation for determining transposition regions for critical storms. Advances in understanding orographic precipitation mechanisms can inform procedures used to implement orographic transposition factors. PMP estimation in mountainous terrain, especially for short durations and small areas, remains a major challenge for PMP estimation.

Conclusion 4-19: Current methods for PMP estimation do not have a solid scientific foundation, but more effective integration of scientific advances into the implementation of procedures can enhance PMP estimates. Model-based estimation methods are required to effectively address the impacts of climate change on PMP and to assess uncertainty of PMP estimates.

NUMERICAL MODELING AND PMP

After the completion of HMR 59, the NWS discontinued PMP work (ACWI, 2018; England et al., 2011), and no advances in numerical weather prediction (NWP) modeling were applied to PMP estimation. The WMO (2009) PMP guidance did not

include NWP and was critical of models, stating: “Physical models are not usable as they produce low-accuracy estimates of precipitation. The use of numerical weather models for PMP estimation is currently a topic of research (Cotton and others, 2003).” A recent summary of PMP methods did not mention storm models or use of NWP (Mukhopadhyay and Kappel, 2017).

The PMP practices from the 1970s though 1990s, the WMO statements, and recent summaries do not accurately reflect advances in NWP and modeling of extreme precipitation over the past 30 years that are relevant for PMP estimation (see Chapter 3). Recent statewide PMP studies generally follow HMR techniques of maximization and transposition. They utilize conceptual factors to transpose storms to account for terrain effects on moisture (see above section). These geographic transposition factors are not a conceptual model of atmospheric dynamics, storm mechanisms, or orographic precipitation; they only reflect climatological and geographical adjustment. NWP modeling conducted over the past decade provides potential opportunities for investigating and informing alternative approaches to estimating PMP.

Potential Opportunities and Insights from NWP

Atmospheric modeling has provided an alternative approach for addressing orographic precipitation mechanisms and estimating PMP using NWP (e.g., Chen and Hossain, 2016; Chen et al., 2017; Hiraga et al., 2021; Mahoney et al., 2013; Ohara et al., 2011; Toride et al., 2019; Trinh et al., 2022b; Yang and Smith, 2018). The basic notion is to directly assess the geographic variation in PMP through modeling analyses that, in the best of worlds, can faithfully reproduce the physical processes at play. Modeling studies have also been used to examine assumptions underlying orographic precipitation procedures used for PMP (Cotton et al., 2003; Mahoney et al., 2012; Yang and Smith, 2018). The conclusions of the 1994 PMP study concerning PMP and orographic precipitation still hold. Advances in understanding and modeling extreme rainfall in complex terrain will be key to major advances in PMP.

Over the past decade, climate modeling has been explored as a component of PMP analyses and to estimate PMP. Research includes a broad range of models and techniques (e.g., Chen et al., 2017; Gangrade et al., 2018; Hiraga et al., 2021; Ishida et al., 2018; Kunkel et al., 2013b; Mahoney et al., 2022; Ødemark et al., 2021; Ohara et al., 2011; Rastogi et al., 2017; Tarouilly et al., 2023; Trinh et al., 2022b). Maximum precipitation estimation using NWP (particularly for ARs along the West Coast) has been explored using variations of maximization and transposition methods, such as moisture maximization at the model boundary and shifting of the model domain (Ohara et al., 2011; Toride et al., 2019). Reconstruction of TC rainfall fields with models and exploration of transposition and potential maximization has been investigated (Mure-Ravaud et al., 2019a, b). Modeling studies have been used for reconstructing major historical events for enhancing storm catalogs and for constructing storm catalogs based on climate change scenarios (e.g., Mahoney et al., 2022). A range of techniques has been employed to assess uncertainties in PMP based on climate model simulations. Climate modeling approaches to PMP create opportunities for statistical characteriza-

tion of uncertainties in PMP estimates (see Chapters 3 and 5). These research studies illustrate the potential for using models to enhance PMP estimation. The results have not yet been translated to developing PMP products for many locations.

IMPLICATIONS OF CLIMATE CHANGE FOR PMP

Introduction

A notable limitation of traditional PMP estimation is its assumption of a stationary climate, disregarding evidence indicating shifts in extreme precipitation and in key meteorological factors linked to extreme storms, notably atmospheric moisture, in a warming climate. With rare exceptions, PMP estimates, as they are presently employed in decision making for federal, state, and local infrastructure in the United States, have not been directly influenced by information related to climate change (Mahoney et al., 2018). State-level and site-specific PMP studies often acknowledge the potential role of climate change on PMP but have recommended that the current practice should not be modified to address climate change (AWA, 2015; Mahoney et al., 2018). Among the federal agencies, USACE (2016) recognizes the lack of a substantial body of research to enable quantitative estimation of the relationship between climate change and extreme storms.

In the United States, only Colorado has explicitly included climate change in its official implementation of PMP (State of Colorado, 2020). Nonetheless, there are ways to at least partially include climate change effects in otherwise conventional PMP estimates, and emerging model-based techniques for estimating PMP can also partially include climate change effects. Future alterations in moisture levels, atmospheric dynamics, storm intensity, duration, and the efficiency and type of precipitation will collectively contribute to shifts in precipitation extremes. Of these, the thermodynamic effect is most easily incorporated into PMP estimates (see Conclusion 3-10). While there is robust confidence in the direction and approximate magnitude of change in thermodynamic aspects, including the rise in large-scale temperature and moisture levels, confidence wanes when it comes to alterations in circulation-based and dynamic effects, especially their manifestation in local-scale extreme events.

Because extreme precipitation events are highly localized occurrences, the substantial uncertainties surrounding dynamic effects pose a challenge to integrating climate change information into a fully deterministic framework (Mahoney et al., 2018). Nevertheless, considering the high degree of assurance that some form of change is likely, along with the relatively strong confidence in the mechanisms driving thermodynamic changes, incorporating basic estimates of trends into PMP estimates is justified.

Several approaches have been proposed but not implemented as standard practice. In the United States, USBR, focusing primarily on dam safety, has investigated the effects of climate change on PMP since about the mid-1990s (Eddy, 1996; England et al., 2011; Jensen, 1994; Sankovich et al., 2012; Toride et al., 2018). However, except in rare instances, such studies have not led to the formal adoption of climate change into operational practice. Because quantitative estimates of extreme rainfall, including