Development, Implementation, and Evaluation of Community-Based Suicide Prevention Grants Programs: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 3 Considerations for Program Development and Oversight and Grantee-Level Implementation and Performance Metrics

3

Considerations for Program Development and Oversight and Grantee-Level Implementation and Performance Metrics

Building on the program examples presented in the preceding session, the next workshop session focused on considerations for program development and oversight, as well as grantee-level implementation and performance metrics. These closely connected topics were addressed together in a single session to foster cohesive dialogue on design, delivery, and oversight. The session opened with a series of brief presentations that provided a foundation for two moderated panel discussions. The first panel discussion focused on lessons learned from the programs described in the previous session. In the second panel discussion, other invited experts offered perspectives on questions related to program development, oversight, and implementation. The session concluded with a round of audience Q&A.

With emphasis on the public health approach, this chapter presents practical strategies for designing and overseeing non-clinical suicide prevention programs implemented at the community level. Drawing on foundational presentations and two panel discussions, participants explored how programs can be tailored to local capacity, needs, and cultural context; supported through proactive technical assistance; and evaluated using realistic metrics that reflect incremental progress. Additional topics included the development of theories of change and logic models, the use of dashboards and storytelling to communicate impact, equitable funding structures, and approaches to cultivating strong grantee networks and clarifying inclusion criteria.

FOUNDATIONAL PRESENTATIONS

Foundational presentations covered a range of topics. Following an introductory talk, presenters addressed the public health approach to comprehensive suicide prevention, models for effective community-based programs, the development of logic models, strategies for providing comprehensive technical assistance, and the use of data dashboards to support program implementation and oversight.

Theory of Change, Theory of Action, and Performance Metrics

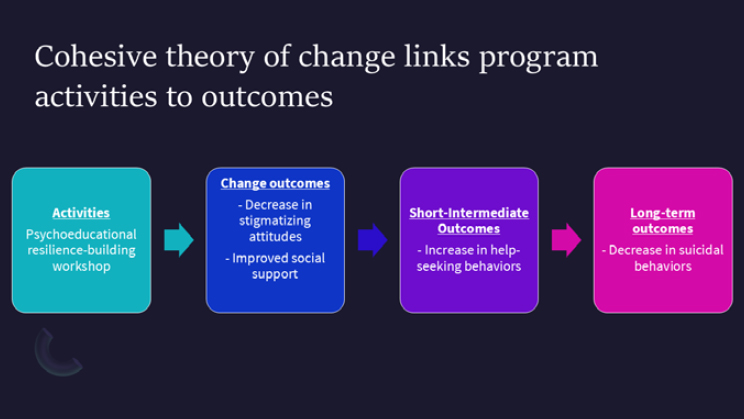

Daniel Friend (Mathematica; member, workshop planning committee) kicked off the session with a presentation assembled in collaboration with Elly Stout (Education Development Center [EDC]; member, workshop planning committee). Friend opened by highlighting the importance of grounding programs in a cohesive theory of change and identifying realistic performance metrics. He noted that context is key, and it is important to consider who is being served by a program. A cohesive theory of change links program activities to their intended outcomes. Friend explained that the structure begins with activities—the mechanisms through which change is introduced—and then flows through a logical sequence of outcome stages:

- Change outcomes refer to proximal effects, such as shifts in attitudes, knowledge, or skills.

- Short- and intermediate-term outcomes reflect more distal changes, such as sustained use of knowledge and skills.

- Long-term outcomes represent broader population health improvements.

Friend used a psychoeducational workshop focused on resilience-building as an illustrative example of a cohesive theory of change (see Figure 3-1). A successful activity of this kind might reduce stigmatizing attitudes and improve social support (change outcomes), which in turn could increase help-seeking behaviors (intermediate outcome), ultimately contributing to a reduction in suicidal behaviors (long-term outcome).

Friend emphasized the distinction between a theory of change (which explains how change is achieved) and a theory of action (which ensures implementation quality). The latter is supported by performance metrics—quantitative indicators that track progress toward a particular target and guide decision-making (see Figure 3-2). Friend stressed that metrics are a cornerstone of continuous quality improvement. For instance, if a program has a goal of recruiting 100 veterans per month but is only enrolling 12, this indicates a need for strategic adjustment, such as changing

SOURCE: Presented by Daniel Friend on April 29, 2025.

SOURCE: Presented by Daniel Friend on April 29, 2025.

recruitment strategies. Realistic and achievable metrics allow for responsive management and improvement and help to ensure accountability to various stakeholders.

Drawing from experience across programs, Friend identified several common performance metrics that can be adapted based on program context:

- Recruitment and enrollment

- Dose (extent of services received)

- Initial engagement

- Service uptake

- Satisfaction and acceptability to participants

- Fidelity (adherence to the program model)

- Feasibility

- Sustainability

- Cost

Together, all of these metrics not only help ensure accountability but also serve as key inputs into program implementation as well as guiding program evaluation, Friend concluded.

The Public Health Approach and Comprehensive Suicide Prevention

Alex Crosby (Morehouse School of Medicine) provided an in-depth presentation on the public health approach to comprehensive suicide prevention, emphasizing its systematic methodology and application to reducing suicidal behaviors across diverse populations.

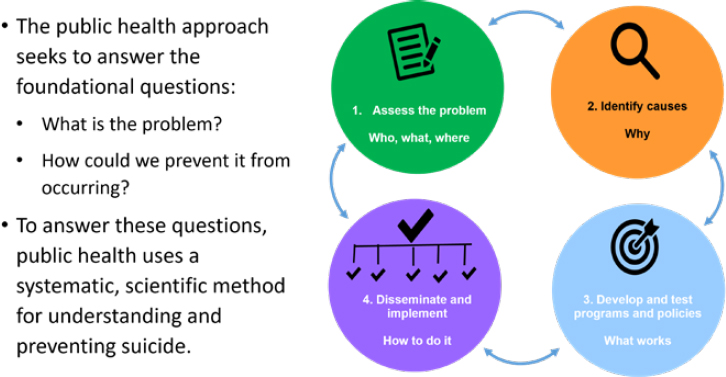

Crosby began by introducing the public health framework, noting its four core components: assessing the problem, identifying causes, developing and testing interventions, and disseminating and implementing successful strategies (see Figure 3-3). This structured method allows public health practitioners to systematically understand suicide-related issues and effectively intervene across different community contexts.

Assessing the problem involves developing understanding of the scope and nature of suicide by examining who is affected, where incidents occur, and the broader circumstances surrounding suicidal behaviors, Crosby explained. Identifying causes involves examining “why” questions, such as why suicide might be more prevalent in one population than another—e.g., urban versus rural, males versus females. After gaining understanding around aspects of the “why,” the next step is developing and testing programs and policies tailored to address these factors. Crosby offered as an example developing an intervention to reduce alcohol misuse because substance misuse, particularly alcohol misuse, is a major risk factor for

SOURCE: Presentation by Alex Crosby on April 29, 2025; based on discussion in Potter and colleagues (1995) and World Health Organization (2014).

suicidal behavior. The final step in the public health approach entails expanding the reach of successful programs and disseminating lessons from such programs.

Crosby highlighted historical trends, noting suicide rates in the United States dating back to the 1930s. He pointed out that during the 1920s and 1930s, the Great Depression significantly influenced higher suicide rates, demonstrating the critical impact of economic factors on suicidal behaviors. Crosby stressed the importance of recognizing the multifaceted nature of suicide, cautioning against attributing rising suicide rates to any single factor, but rather understanding it as resulting from complex interactions of multiple determinants.

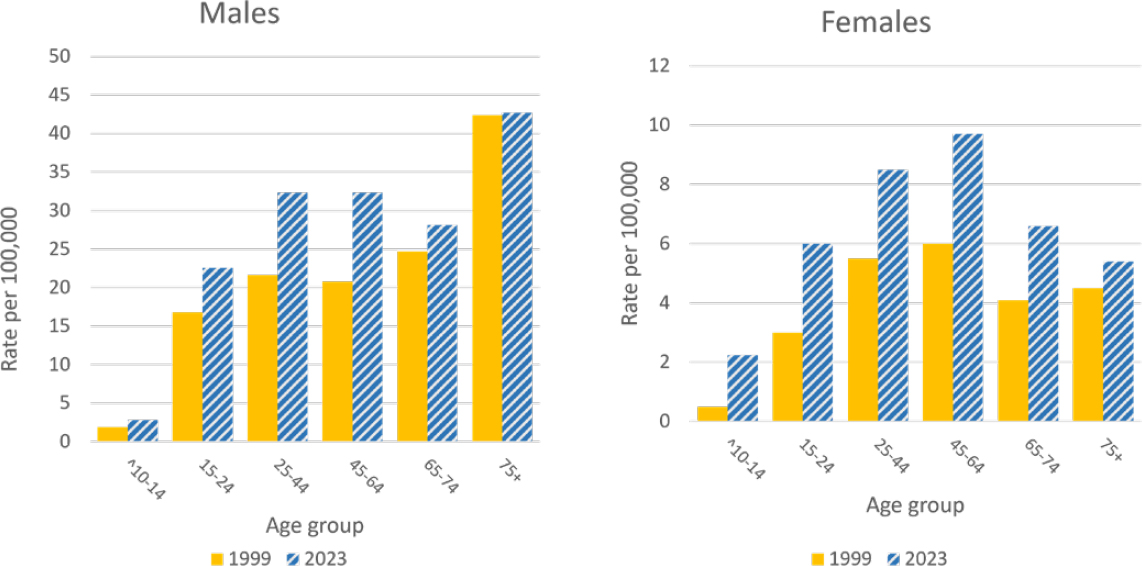

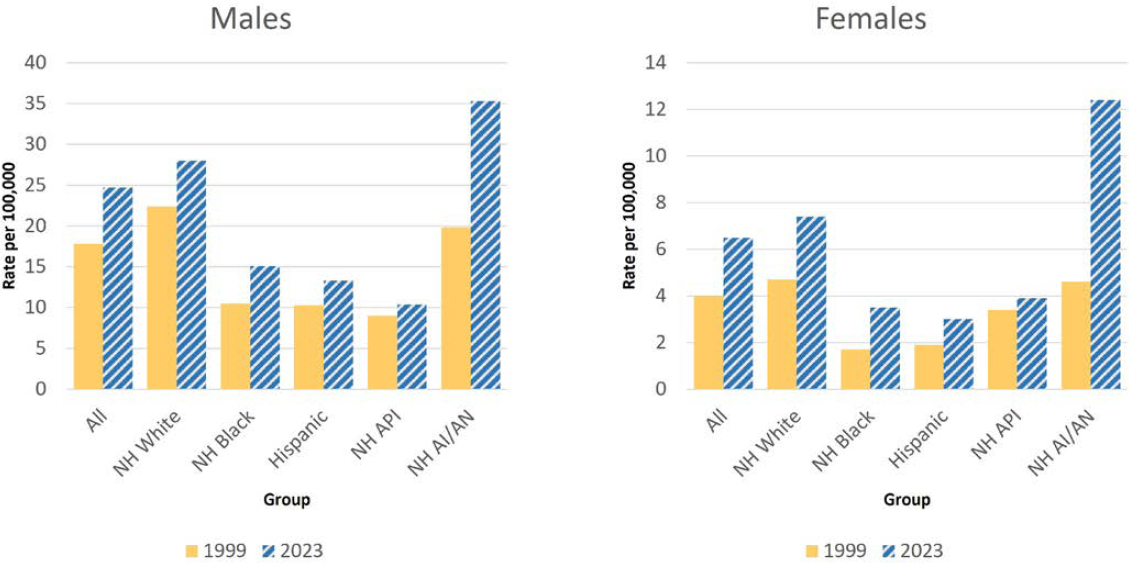

Examining recent trends, Crosby presented data showing increased suicide rates across various demographic groups, including age, sex, and racial/ethnic categories. Between 1999 and 2023, suicide rates notably increased across almost all age groups for both males and females, except for males aged 75 and older, where rates remained relatively stable (see Figure 3-4). Similarly, data disaggregated by race and ethnicity indicated increasing suicide rates among White, Hispanic, Black, and Asian American populations, and particularly high increases among American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Crosby emphasized this widespread increase to underline the need for broad-based suicide prevention efforts (see Figure 3-5).

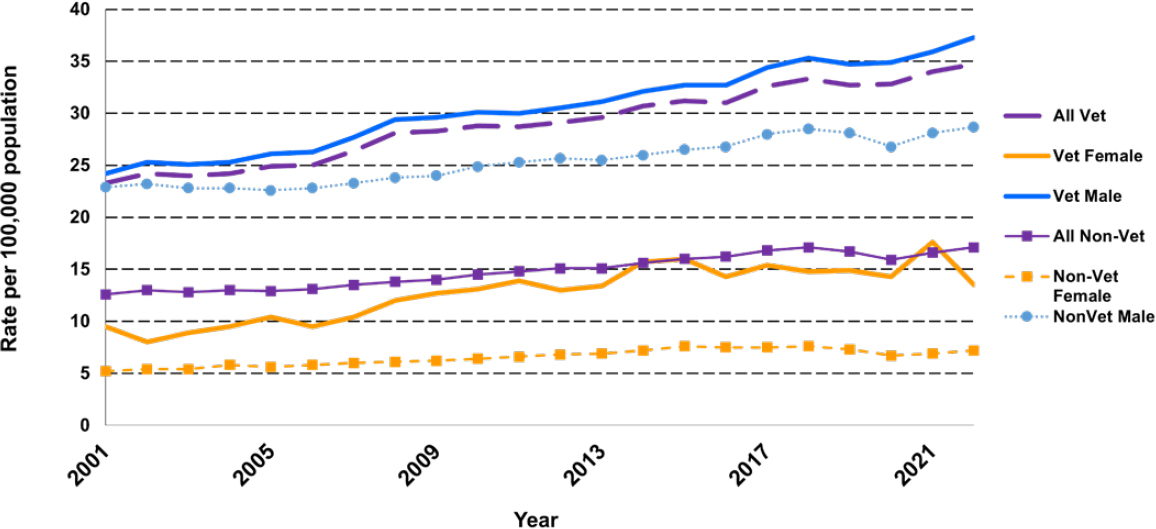

Crosby also highlighted suicide rates among veterans (see Figure 3-6) compared to non-veterans, revealing ongoing challenges despite slight

SOURCE: Hedegaard and colleagues (2020). Presentation by Alex Crosby on April 29, 2025.

SOURCES: Presentation by Alex Crosby on April 29, 2025; based on data from CDC Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS, https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html) and Curtin and Hedegaard (2019).

SOURCE: Presentation by Alex Crosby on April 29, 2025; based on data in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2024).

improvements in recent years. This underscored the importance of targeted suicide prevention strategies tailored specifically to the veteran community.

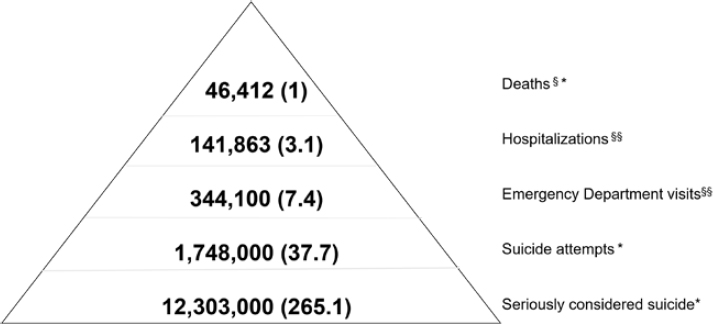

Crosby explained that it is important to consider the impacts of suicidal behaviors beyond mortality. Suicide-related hospitalizations, emergency department visits, reported attempts, and serious ideation occur with progressively greater frequency. While approximately 46,000 suicides occurred in 2021, millions more experienced serious suicidal ideation or attempts, representing critical intervention opportunities to prevent suicides, Crosby noted (see Figure 3-7). He added that those at risk of suicide are often dealing with multiple issues that can be at the individual level, at the family or peer level, at the community level, or at the societal level. For example, an individual might be facing housing insecurity, chronic illness, and hunger or food insecurity simultaneously. Intervening on just one of these issues might be enough to decrease their risk for suicidal behavior, Crosby suggested.

Crosby outlined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Comprehensive Suicide Prevention program, describing key components such as strong leadership, multisectoral partnerships, and the use

NOTE: Numbers in parentheses indicate the ratio of each category relative to suicide deaths.

§ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) National Vital Statistics System (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/index.htm).

§§ CDC’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-All Injury Program (https://www.cpsc.gov/Research--Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data).

* Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health (https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health).

SOURCE: Presentation by Alex Crosby on April 29, 2025; Crosby and colleagues (2011).

of data-driven strategies. He discussed CDC’s approach to identifying disproportionately affected populations—populations that experience rates of suicide greater than the general population, which include veterans, tribal populations, rural communities, LGBTQ+ individuals, and youth.

To illustrate comprehensive suicide prevention strategies, Crosby described CDC’s Suicide Prevention Resource for Action, which identifies specific strategies and approaches supported by evidence (see Table 3-1). Crosby pointed out evidence indicating that communities implementing multiple strategies simultaneously experienced greater success compared to those employing single-strategy interventions.

In describing upstream suicide prevention, Crosby referred to the visual metaphor illustrated in Figure 3-8. He likened suicide risk to individuals falling through a gap in a bridge into a river leading to a waterfall downstream, describing different points along the river where interventions might occur. As shown in the figure, the furthest upstream strategy is to repair the gap in the bridge, an approach Crosby equated with strategies such as strengthening economic supports and building coping and problem-solving skills. Midstream interventions might focus on reducing substance misuse, while crisis response is often necessary downstream. Crosby emphasized that public health approaches, including those discussed throughout the workshop, address all of these levels simultaneously. However, he stressed that upstream strategies tend to be the most effective and cost-efficient. Even so, midstream and downstream interventions remain vital, as not everyone can be reached early.

TABLE 3-1 Comprehensive Suicide Prevention Strategies and Approaches

| Strategy | Approach |

|---|---|

| Strengthen economic supports | Household financial security, housing stabilization policies |

| Create protective environments | Reducing access to lethal means, organizational policies, community-based alcohol reduction policies |

| Strengthen access and delivery of suicide care | Mental health coverage, reduce provider shortages in underserved areas, safer suicide care through systems change |

| Promote healthy connections | Peer norm programs, community engagement activities |

| Teach coping and problem-solving skills | Social-emotional learning programs, parenting skills and family relationship approaches |

| Identify and support people at risk | Gatekeeper training, crisis intervention, treatment for at-risk individuals, prevention of re-attempts |

| Lessen harms and prevent future risk | Postvention activities, safe reporting and messaging about suicide |

SOURCE: Presentation by Alex Crosby on April 29, 2025; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022).

SOURCE: Presentation by Alex Crosby on April 29, 2025; Wisconsin Department of Health Services (n.d., p. 1), reprinted with permission.

Concluding his presentation, Crosby reiterated that suicidality is a critical, multifaceted public health issue. He stressed the necessity of a comprehensive, evidence-informed approach, emphasizing that effectively addressing suicide requires interventions at multiple levels—individual, family, community, and societal. Crosby affirmed that tailored strategies responsive to specific community needs and protective factors are essential for meaningful reductions in suicidal behaviors.

Models for Effective Community Suicide Prevention

Stout presented an overview of models and tools that can support the design and implementation of effective community-based suicide prevention efforts. She emphasized the importance of helping communities adapt concepts and strategies to fit their specific needs, assets, and levels of readiness.

Stout opened by noting that community suicide prevention has long been a priority in national strategies, including the 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention and more recent updates. While national strategies outline broad goals and objectives, Stout explained, relatively few models are available that translate those goals into actionable guidance for communities. She highlighted three frameworks that offer communities clear direction on both what to implement and how to implement it.

The first framework Stout mentioned was the CDC Suicide Prevention Resource for Action, which outlines evidence-informed strategies for reducing suicide risk. As described earlier in Crosby’s presentation on the public health approach and comprehensive suicide prevention, this resource identifies multiple areas for intervention that, when combined, are associated with greater impact (see Table 3-1). Stout clarified that CDC’s resource focuses on broad strategies—such as strengthening economic supports or creating protective environments—rather than prescribing specific programs. The goal, she said, is to help communities prioritize and combine strategies based on their own context.

Stout next discussed the Suicide Prevention Resource Center’s (SPRC’s) Comprehensive Approach to Suicide Prevention,1 which predates the CDC model but includes many of the same elements (see Figure 3-9). She described the visual representation of the model as a puzzle, with interconnected components that collectively support a comprehensive approach. Importantly, she noted that this is not a checklist; communities are not expected to implement every element. Rather, the model can help community stakeholders identify where they are currently investing and where additional focus may be needed.

To complement the SPRC framework, Stout introduced SPRC’s Strategic Planning Approach, which offers a step-by-step process for tailoring community suicide prevention strategies (see Figure 3-10). The process includes assessing suicide-related risk and protective factors in the local community, identifying populations at highest risk, and taking stock of the local context, including assets and opportunities. From there, community leaders can select appropriate strategies from the CDC or SPRC models and identify culturally appropriate programs or practices for implementation. Evaluation is the final step in the cycle, allowing communities to assess whether they are making measurable progress toward reducing suicidal behaviors.

Stout then turned to a third model—EDC’s Community-Led Suicide Prevention approach—which builds on the CDC and SPRC frameworks and incorporates insights from a 2017 National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention report on transforming communities. That report reviewed global examples of community-based suicide prevention efforts and identified seven key elements that contribute to success (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2017):

- Unity

- Strategic planning

___________________

1 SPRC (https://sprc.org/) is a SAMHSA-funded resource center focused on advancing the implementation of the U.S. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/national-strategy-suicide-prevention.pdf).

SOURCE: Presentation by Elly Stout on April 29, 2025; SPRC (2020a). Developed by Education Development Center (EDC) at the University of Oklahoma under a cooperative agreement funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Copyright © 2020 by the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma.

SOURCE: Presentation by Elly Stout on April 29, 2025; SPRC (2020b). Developed by Education Development Center (EDC) at the University of Oklahoma under a cooperative agreement funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Copyright © 2020 by the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma.

- Integration

- Sustainability

- Data

- Fit

- Communication

Stout highlighted two of these components due to their relevance to discussions at this workshop. She explained that the unity component involves bringing community partners together and building consensus. With regard to the data component, she noted that it involved considering the local context and pointed to the White Mountain Apache surveillance system discussed earlier in the workshop (see Chapter 2) as an example of a culturally appropriate data system that also supports sustainability and effective communication.

Stout concluded by underscoring the value of grounding grant programs and community initiatives in structured, evidence-informed models. Doing so, she said, helps ensure that strategies are aligned with community needs and priorities, and gives communities a way to assess whether they are making progress toward meaningful outcomes. She encouraged participants to explore publicly available resources from CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022), EDC (Education Development Center, 2025), the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (2017), SPRC (2020a,b), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2024), and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2018).

Developing Logic Models for Community-Based Suicide Prevention

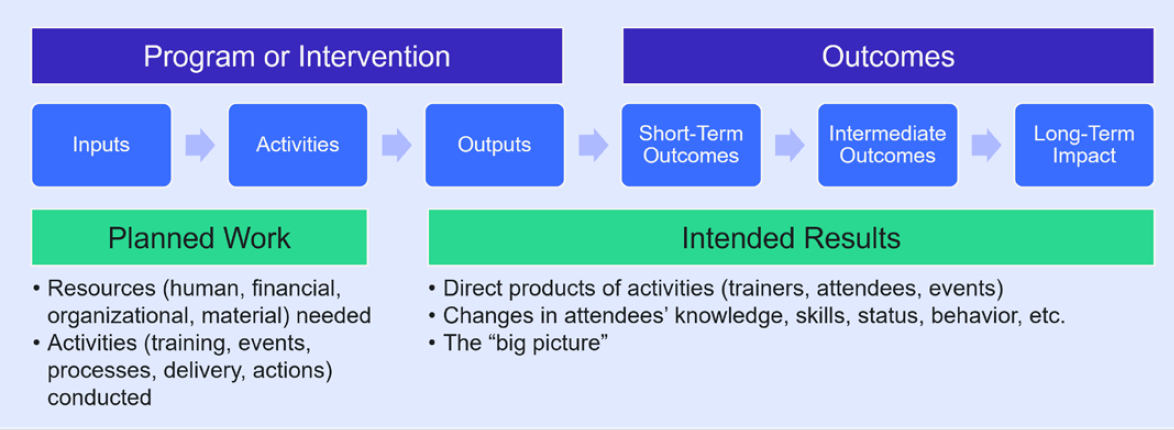

Corbin Standley (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [AFSP]2) presented an overview of logic models and their role in guiding evaluation of community-based interventions. He described logic models as visual roadmaps that explain the relationship between a program’s activities and its intended outcomes, provide a framework for both implementation and evaluation and making explicit the program’s underlying logic. He added that logic models are typically one-page, iterative documents that evolve as programs mature and data become available.

Standley explained that logic models often include five core components:

___________________

2 AFSP (https://afsp.org/) is a voluntary health organization dedicated to saving lives and bringing hope to those affected by suicide, including those who have experienced a loss. AFSP creates a culture that’s smart about mental health through public education and community programs, develops suicide prevention through research and advocacy, and provides support for those affected by suicide.

- Goals, which define the overarching purpose of the program;

- Learning objectives and program objectives;

- Processes and activities carried out as part of the program;

- Outcomes, including short-term and long-term changes; and

- Context, which accounts for cultural and community considerations.

He underscored the importance of cultural humility and cultural appropriateness, working with the community to define problems needing to be addressed along with desired solutions.

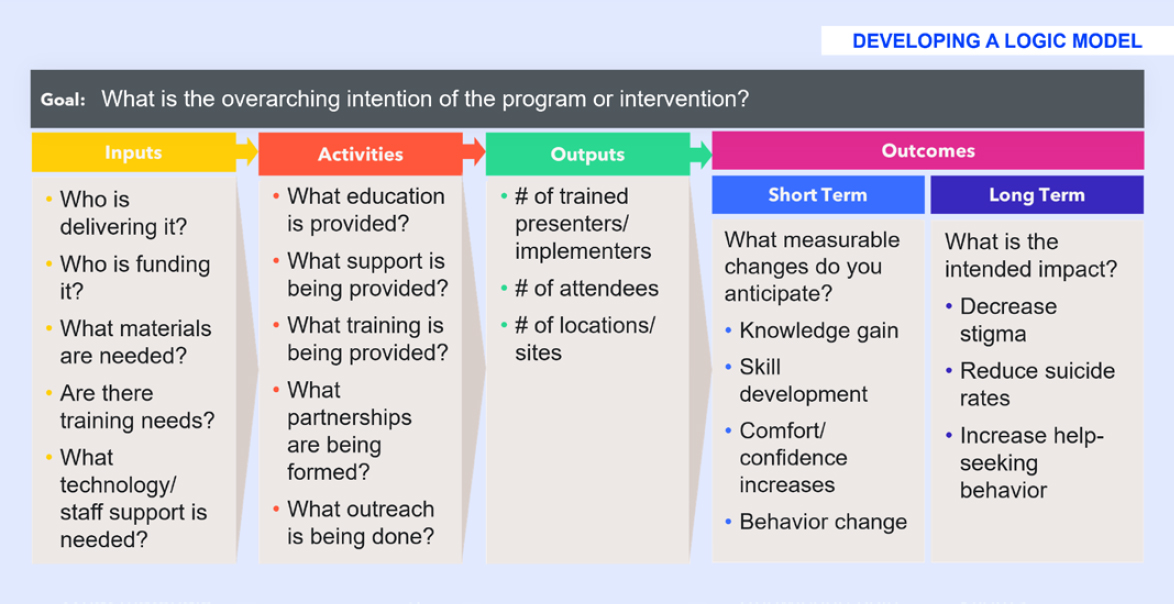

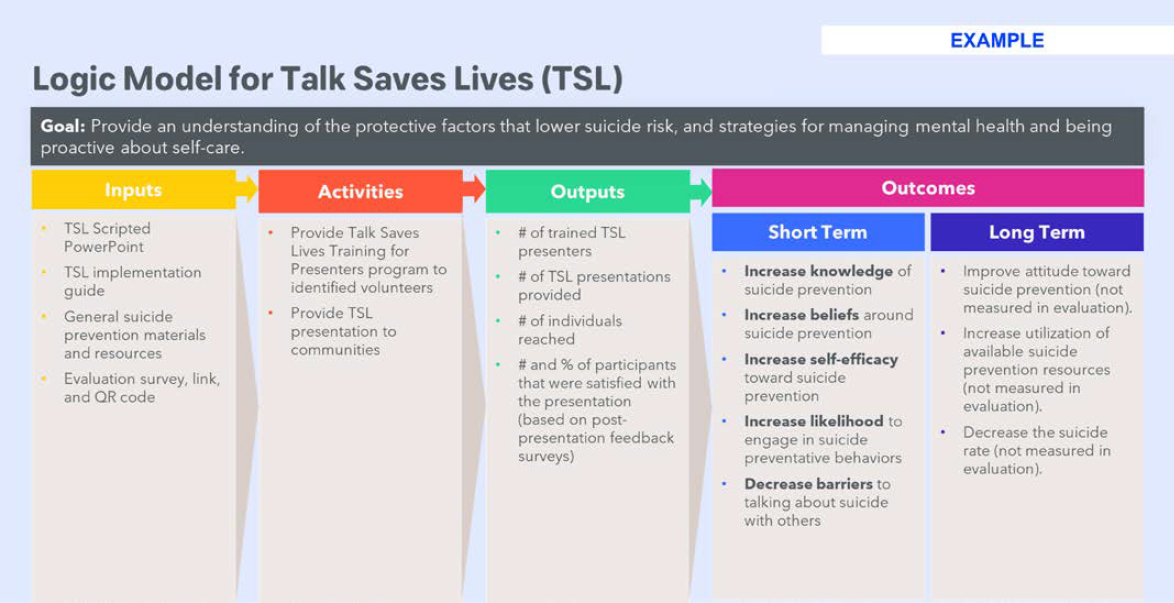

To help orient the audience to terminology, Standley introduced a general template showing the relationship between inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and long-term impacts (see Figure 3-11). The framework shows how inputs such as funding, personnel, and materials support activities like training or outreach, which lead to outputs (e.g., number of presentations or attendees) and short-term outcomes—measurable changes you anticipate immediately following a program or intervention, such as knowledge gain or skill development. These, in turn, contribute to longer-term outcomes like reduced stigma, increased help-seeking behavior, and ultimately reduced suicide rates.

Standley then walked through a more detailed breakdown of each logic model component, offering specific guiding questions and prompts for program planners (see Figure 3-12A). For example, when defining inputs, program planners might ask what materials, training, and technology are needed. To illustrate how these principles are applied in practice, Standley shared a logic model used by the AFSP for its flagship education program, Talk Saves Lives (see Figure 3-12B). Inputs for the program include a scripted PowerPoint, an implementation guide, and evaluation tools. Activities include training volunteer presenters and delivering presentations in communities. Outputs track the number of trainings, attendees, and participant satisfaction. Short-term outcomes include increased knowledge of suicide prevention, improved attitudes and beliefs, greater self-efficacy, and reduced barriers to talking about suicide. While long-term impacts such as reduced suicide rates are more difficult to measure directly, they remain central goals.

Comprehensive Technical Assistance to Support Program Outcomes

Carrie Farmer (RAND Corporation) offered reflections on the role of technical assistance as a strategic tool for helping community-based programs monitor their performance and achieve success. Echoing earlier remarks, Farmer noted that grantees and community-based organizations can have mixed capacities for data collection, evaluation, and reporting depending on how big or small they are; availability of financial,

SOURCE: Presentation by Corbin Standley on April 29, 2025; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

SOURCE: Presentation by Corbin Standley on April 29, 2025; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

SOURCE: Presentation by Corbin Standley on April 29, 2025; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

technological, and other resources; staff expertise; and connections to other expertise.

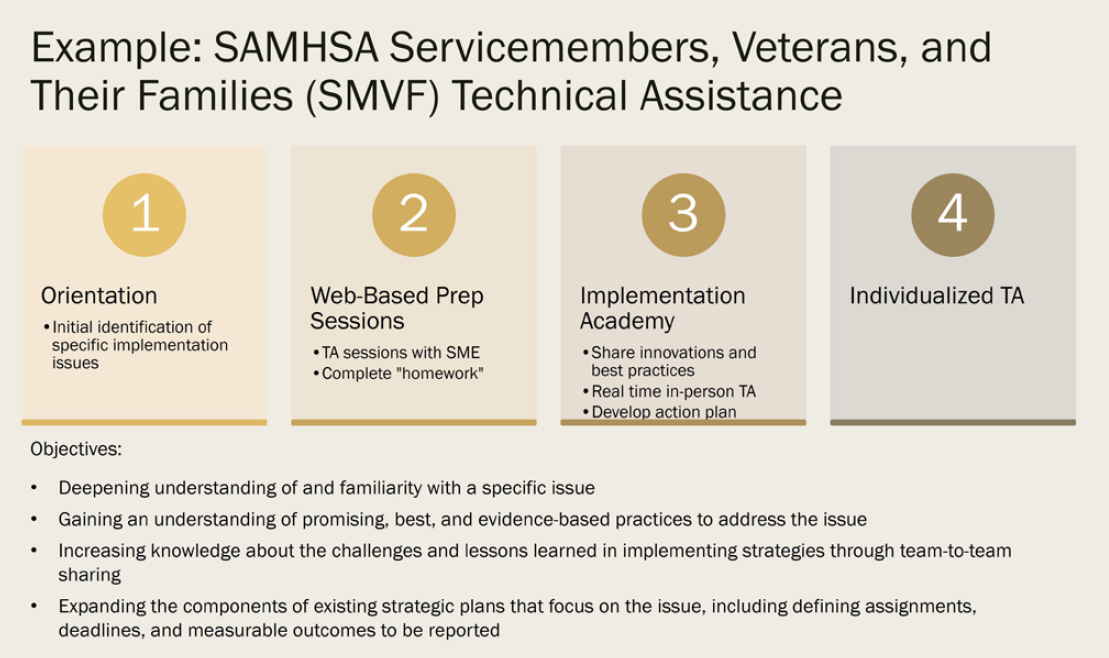

Farmer explained that traditional technical assistance typically involves providing on-demand assistance for specific problems as they arise over the course of program design, implementation, and evaluation. In contrast, comprehensive technical assistance is more proactive and takes a long-term approach, with a goal of building knowledge and capacity for grantees to collect and evaluate outcomes on their own, thus reducing their reliance on technical assistance in the future.

A comprehensive approach can help align grantees around the measurement of priority outcomes the funder is interested in, thus ensuring relevant data are collected, Farmer noted. It can also build a cohort of programs or grantees so they can learn from each other and share best practices. Comprehensive technical assistance may include one-on-one coaching, in-depth assessment of grantee needs, development of individualized support plans, and active tracking of grantee progress over time.

Farmer pointed to the technical assistance provided by SAMHSA’s Service Members, Veterans, and their Families (SMVF) Technical Assistance Center3 as a promising comprehensive support model (see Figure 3-13). She described what is entailed in each of the model’s four phases:

- Phase 1 focuses on orienting each grantee to the intervention through a cohort-based model that ensures fidelity to the program’s core components. This phase emphasizes level-setting and understanding the context of each specific grantee.

- Phase 2 consists of a series of web-based preparatory sessions that introduce foundational concepts. Through presentations by subject matter experts, grantees receive structured education on key topics such as evidence-based practices, logic model development, and data management—including how to collect, interpret, and store data effectively.

- Phase 3 brings grantees together for an Implementation Academy. During the Academy, grantees deepen their understanding of the specific issue(s) they are working to address, strengthen their ability to implement it successfully, and learn from lessons shared by peers and experts. This phase helps organizations identify suitable evidence-based practices, understand implementation challenges, and develop strategic implementation plans.

___________________

3 The Service Members, Veterans, and their Families Technical Assistance Center (https://www.samhsa.gov/technical-assistance/smvf), supported by SAMHSA, acts as a national resource that helps states, territories, tribes, and local communities build their capacity to meet the behavioral health needs of military and veteran families.

NOTE: SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

SOURCE: Presentation by Carrie Farmer on April 29, 2025; SAMHSA Service Members.

- Phase 4 consists of individualized technical assistance. This ongoing support helps grantees troubleshoot challenges, adapt practices as needed, and sustain implementation quality over time.

Farmer underscored the value of the model’s heavy focus on implementation, noting that desired outcomes will not be achieved if the intervention is not implemented well from the start.

Service Members, Veterans, and Their Families Technical Assistance Center

The SMVF Technical Assistance Center’s approach to comprehensive technical assistance might serve as a useful model for the Sergeant Parker Gordon Fox Suicide Prevention Grant Program, Farmer noted. She suggested several specific elements that could strengthen the Fox program’s technical assistance approach. These include offering virtual workshops on topics such as evaluation design, data collection, data analysis, and communication. Farmer emphasized the importance of one-on-one technical assistance, as grantee needs can vary widely—some organizations may require support in identifying appropriate metrics, while others may need guidance in navigating institutional review board processes. She also recommended the development of evaluation support tools, such as a curated catalogue of process and outcome measures, as well as the creation of a community of practice that would allow grantees to learn from one another.

Design of Actionable Dashboards for Supporting Program Implementation and Oversight

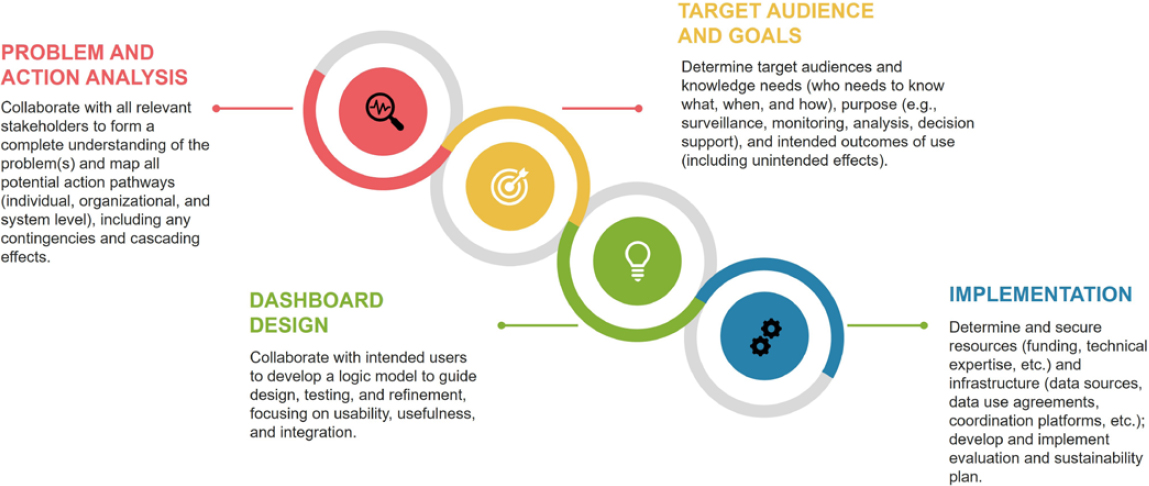

Itzhak Yanovitzky (Rutgers University) provided an overview of how dashboards can serve as actionable tools in support of public health initiatives. Drawing from his expertise in behavioral and social change communication, he discussed how dashboards—when properly designed and implemented—can be leveraged not only for monitoring and dissemination but also for strategic planning, goal setting, coordination, and system learning.

He emphasized that while dashboards are often used to track program performance or report outcomes, they hold broader potential to advance decision-making and catalyze action. Actionable dashboards can permit real-time access to curated data, enable users to visualize trends and detect bottlenecks, support implementation decisions, and connect stakeholders across systems. As illustrated in Figure 3-14, dashboard design involves a range of decisions regarding data, users, and purpose—from monitoring and communication to alignment and learning.

SOURCE: Presentation by Itzhak Yanovitzky on April 29, 2025.

However, Yanovitzky cautioned that building a dashboard alone does not guarantee its usefulness or use. Simply providing access to data does not mean people will use it—or use it well. He outlined several factors that determine whether a dashboard actually influences behavior or supports action. These include the characteristics of the data itself (e.g., timeliness, granularity), user capacity and needs, the purpose of the dashboard (strategic vs. tactical), the design elements (interactivity, customization), the context in which the dashboard is being introduced (e.g., policy environment, user norms), and whether it is integrated into existing workflows.

Dashboards, Yanovitzky noted, often fail when developed in isolation from their intended users. To overcome this challenge, he proposed an “actionability by design” approach—a process that brings together program staff, data scientists, and end users to co-create dashboards that meet real-world needs and achieve three overlapping goals: usability, usefulness, and integration (see Figure 3-15). Yanovitzky explained that usability refers to whether a dashboard is intuitive, efficient, and accessible. Usefulness reflects whether it delivers timely, context-relevant information that supports decision-making. Integration requires that dashboards become embedded into daily workflows and organizational culture. If a dashboard is not used consistently, it will not achieve its intended purpose, he stated.

Yanovitzky described “actionability by design” as a collaborative, iterative process that begins with identifying shared problems and mapping pathways for action. From there, the team defines data needs, develops the dashboard collaboratively, and periodically refines it while addressing potential unintended consequences.

Yanovitzky also stressed that dashboards must be tailored to the specific context and application; they are not templates. He shared a concrete example from New Jersey, where a statewide opioid dashboard was developed through inter-agency collaboration. The project began with public town halls and evolved into a tool that allowed for cross-county learning, resource mapping, and alignment of services across government systems. He concluded his presentation by reiterating that such an impact is only possible when the dashboard design process is grounded in early and sustained collaboration with stakeholders.

PANEL DISCUSSIONS AND AUDIENCE Q&A

After the foundational presentations, the session moved to a series of two moderated panel discussions. The first panel discussion focused on lessons learned from the examples of programs supporting non-clinical community-based suicide prevention efforts discussed earlier in the day. The second panel discussion provided the opportunity for other invited experts to offer additional insights. Audience Q&A followed the panel discussions.

SOURCE: Presentation by Itzhak Yanovitzky on April 29, 2025.

Lessons Learned from Examples of Non-Clinical Community-Based Suicide Prevention Efforts

Colin Walsh (Vanderbilt University; member, workshop planning committee) served as moderator for both panel discussions summarized in this chapter. The first panel discussion was with the individuals who had given the presentations summarized in Chapter 2: Mary Cwik (Johns Hopkins University), Novalene Alsenay Goklish (Johns Hopkins University), Brandi Jancaitis (Virginia Department of Veterans Services), Richard McKeon (SAMHSA), and David Rozek (University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio). Topics included structuring programs to minimize grantee burden, fostering collaboration and peer learning, tailoring outreach and respecting community readiness, planning for evaluation and communication of findings, and reflections on grant design and adaptation.

Structuring Programs to Minimize Grantee Burden

Walsh began the moderated panel discussion by asking panelists to share lessons learned around how to structure programs to minimize burden on grantees. Jancaitis noted that this is an important question that she and her team grapple with daily. As their grant sizes are relatively small ($75,000 to $175,000 per grantee, which may barely fund a full-time staff member depending on level of staffing), grantees have to be creative in how they use that investment. Jancaitis added that the small awards drew grantees that might have smaller infrastructures, so expectations for impact needed to be realistic. She noted that they begin providing technical assistance before the grant is awarded to help grantees with awareness of resources and where to go for data to help define the need, as well as capacity to put together a basic logic model. In addition to pointing to best practices, technical assistance providers answered questions as prospective grantees put together their applications and continued to layer resourcing in between their reporting cycles. Jancaitis emphasized that a core lesson learned was that technical assistance has to start from the beginning and continue throughout the program.

Rozek also commented on the work that is needed to support prospective grantees prior to receiving an award. He and his team approach support for prospective grantees as building a partnership and examining how they might help with infrastructure or barriers to starting the work. As an example of the latter, he noted that some organizations might have hiring restrictions that require funding to have been received before a position can be posted. Given that there might be a lag time of three months or more between the start of the grant period and receipt of funding, this can present challenges if funding is not for a multi-year period. Rozek noted that they

will work with grantees to scope out an appropriate initial project from which they can build capacity into potential future funding cycles or grant opportunities, thus setting up organizations for success. Additionally, the first grant to an organization may be focused on building or strengthening their infrastructure; the outcomes of that infrastructure grant will not be an immediate large-scale impact, he stated, but it will enable an organization to hire key staff and build out programmatic areas, which Face the Fight views as important progress and can set the organization up for larger and more lasting impact over time.

Making sure the grant truly supports what communities want to do is first and foremost, Cwik added, so it is critical to get community input on how these grants are structured. Community partners should be involved in shaping reporting requirements and data collection, so they understand why funders want that information; this helps teams to get on board with the burden of gathering that information. Cwik stated that reporting is an area where they provide a lot of technical assistance to support, because teams want to be out there helping community members at risk for suicide, rather than focusing time on grant reports. Their technical assistance providers try to reduce the reporting burden. She also stressed the importance of offering flexibility with requirements where possible, as well as grant officers and communities working collaboratively.

Goklish added that grant coordinators and managers based in small rural communities may have to be creative in meeting a grant’s goals and objectives. As an example, she noted that sometimes a tribe may not be willing to share certain data; in such instances, the grant manager has to determine what can be reported on instead. They often start by doing a small pilot of a program before implementing it on a wider scale; this helps with ensuring that staff understand the goals and objectives, how to relay those goals and objectives to the community members they are working to help, and how to move the program forward, Goklish noted. When a program is struggling initially, they take stock of whether the program aligns with community interest and what changes may be needed to improve the alignment.

For the GLS program, there were grant requirements that were not under the control of the program staff, so their focus was on providing support and building a sense of team with grantees, rather than reducing burden, McKeon explained. At the start of the GLS program, each grantee had a person from SPRC assigned to them to provide technical assistance. A member of the evaluation team also participated on each call with grantees.

Fostering Collaboration and Peer Learning

Several panel members commented on the importance of fostering collaboration and peer learning. Building on his remarks about supporting

grantees through robust technical assistance, McKeon stated that another support strategy employed at GLS is convening grantees together for in-person meetings to facilitate peer learning and information exchange. These meetings provide opportunities outside of the formal evaluation process for grantees to identify and share early successes.

Jancaitis noted that fostering a sense of community among grantees is a focus of the Virginia Department of Veterans Services Suicide Prevention and Opioid Addiction Services program, too. In addition to hosting biannual symposiums for training and networking, the program supports ongoing connection through a grantee newsletter and regular “lunch and learn” sessions.

Rozek emphasized the value of connecting organizations that are doing similar work but may not be aware of one another. He noted that there are lots of groups engaged in very similar efforts—sometimes even using the same terminology—but they are not in conversation. Geographic separation or limited visibility can prevent collaboration, even among groups facing comparable challenges. Facilitating those connections, Rozek suggested, can significantly increase collective impact. Sharing resources can help everyone avoid reinventing the wheel and make each investment go further.

He added that fostering a sense of community among grantees also improves the effectiveness of technical assistance. “We can troubleshoot the same problems a hundred times in a hundred organizations,” Rozek noted, and connecting grantees facing similar barriers and letting them learn from each other can result in more effective problem solving than what is achievable from technical assistance alone. He observed that peer knowledge-sharing has been particularly valuable when organizations have already overcome specific barriers and are willing to share what worked.

Rozek also spoke to the importance of facilitating connection not just among grantees, but between grantees and the broader Face the Fight coalition. “We have a coalition side,” he explained, “and we want our grantees and others doing really amazing work to share ideas, interventions, and programming.” While he acknowledged that suicide prevention is rarely a “one size fits all” endeavor, Rozek emphasized that programs can often be adapted when there is shared interest or alignment. They have had many cases where they have played “matchmaker” between organizations, such as a case where they connected a financial services group that wanted to implement universal screening but was unsure how to respond to a positive screen with another group already doing that work. Such connections, Rozek added, often emerge only because funders, technical assistance teams, and coalition members are all attuned to common needs and challenges across organizations.

Tailoring Outreach and Respecting Community Readiness

Walsh commented on the emerging themes of the cyclical or iterative nature of assistance and support, identifying barriers directly with grantees and working creatively to overcome them, and shaping programs in partnership with grantees. These themes, he noted, offered a useful lead-in to the next question—how to cultivate applicants, particularly in communities that programs may want to reach but that have not historically received strong support for efforts of this kind.

McKeon reflected on the early days of the GLS program and the landscape of suicide prevention at the time it was launched. “You have to understand what the environment was like back in 2004,” he said. “Garrett Lee Smith was the first nationally available funding source for suicide prevention in the United States, so there was a hunger for resources in states and communities across the country.” At that time, eligible applicants included states, tribes, and their designees. McKeon noted that states quickly became aware of the opportunity, in part due to infrastructure already in place through SPRC’s contact with state suicide prevention coordinators. Additional effort was needed to raise awareness among tribal communities, however, he added, requiring explicit attention as the program moved forward.

For the Face the Fight initiative, understanding the current suicide prevention landscape was seen as important to informing their work, Rozek stated. They provided a grant to the RAND Corporation to conduct a landscape analysis for current and emerging work in this area, which was released just prior to the workshop (Ramchand et al., 2025). This analysis will equip Face the Fight to identify potentially scalable programs that may be a fit for their mission.

Jancaitis responded that the organizations her team seeks to bring into the funding portfolio generally fall into two broad categories. The first group is deeply embedded in the military community, with strong military culture and military- or veteran-connected staff. While these organizations tend to be well positioned to serve veteran populations, they may need additional support in areas such as mental health, suicide prevention, and integration with broader service systems. The second group consists of more mainstream organizations with well-established mental health programming but limited experience working with military-connected populations.

Military bases and other military facilities are one possible avenue for reaching the former community, Jancaitis noted, but it is important to consider community needs and approach with cultural sensitivity, particularly in populations where help-seeking can be particularly difficult or even taboo.

Another point Jancaitis emphasized was that outreach and marketing are often undervalued by funders. “You can’t build it and assume they will

come,” she said, particularly when working with populations where help-seeking may be difficult. Now working in a funding role herself, Jancaitis acknowledged the tension funders face, but stressed the importance of integrating outreach into the life cycle of a grant from the outset.

Cwik and Goklish emphasized the importance of cultural sensitivity in thinking about outreach. Cwik noted that they represent a university-community partnership, and while there are other tribes that could be strong candidates to carry out similar work to that of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, their approach has been to share their work in forums that include participants from tribal communities, rather than reaching out to specific communities directly. She added that she does not want to be seen as a university-based researcher pushing what might be perceived as her agenda or her center’s agenda onto another community. Goklish explained that their team does not proactively approach other tribes because, as outsiders, they do not want to imply that a community is struggling with suicide or make assumptions about its needs. “The only time we approach a tribe,” she said, “is if they’ve already reached out to us and we are aware of their situation.”

When another tribe expresses interest in the Celebrating Life program, Goklish’s team is open to collaboration but emphasizes the importance of meeting communities where they are. She underscored that there is no “quick fix” for suicide prevention. “We do not have a happy pill,” she said. “We do not have a program that will fix it all overnight.” It took years to build the White Mountain Apache program, Goklish noted, and other communities should expect a similarly gradual process. She emphasized the importance of starting from the beginning—working closely with the community to implement an approach that is both effective and culturally sensitive. She noted that in many Native American communities, suicide remains a taboo subject, making it especially important to secure support from tribal Elders and leaders in order to move the work forward. Goklish added that her team makes a point of sharing this perspective with communities that reach out. “Sometimes they are not happy about what we have to say,” she acknowledged, “but we believe in being transparent—sharing what we struggled with and why it is important to have community support in place before implementing anything.”

Planning for Evaluation and Communication of Findings

Walsh asked panel members to share insights and lessons learned related to determining the appropriate level of budget and other resources to allocate to evaluation and monitoring. Rozek responded that the appropriate level of budget and resources for evaluation often depends on an organization’s existing infrastructure and capacity. Some of it starts with

understanding how much data is already being collected, what internal expertise exists, and what resources are currently in place, he explained. The more funders and technical assistance providers know about an organization’s baseline capacity, the better they can support the development of an appropriate evaluation budget. Rozek emphasized that the process often begins with building infrastructure tailored to the organization’s current needs, with an eye toward scaling that capacity to meet future evaluation expectations.

Jancaitis mused that she did not have a “magic answer” about the percentage of funding to allocate for evaluation, but, as with outreach, it is important to present it as part of the life cycle of a grant from the beginning. Cwik added that evaluation and monitoring always takes more time and person-effort than is expected. Planning for data analysis to take place in the last month of a grant is not sufficient; data analysis should be put earlier in the timeline.

Thinking in terms of effective resource use, McKeon stated, “If you’re collecting data, use the data. Don’t collect data you don’t need or that you can’t use in the very near future to do the work.” This principle reflects a broader theme raised by several panelists: evaluation should be designed not just for funders, but to inform real-time program improvement and support decision-making at the grantee level.

Additional Reflections on Grant Design and Adaptation

Expanding on a point he raised during his presentation, McKeon reflected on lessons learned from the original design of the Garrett Lee Smith (GLS) grant program and how those insights informed changes to its structure over time. The program initially funded three-year grants, but grantees reported that the effective implementation window was significantly compressed. The first year is often spent gearing up, McKeon explained, and the third year is focused on preparing to close out, which really leaves only one solid year for deep implementation. In addition, mortality data suggested that while some GLS-funded interventions were having an impact, those effects tended to fade after the grant period ended. To address these challenges, the grant model was revised. Rather than awarding $400,000 per year for three years ($1.2 million total), the program began offering five-year grants totaling $3.6 million—effectively tripling the available funding over a longer time horizon. McKeon noted that this adjustment appeared to yield stronger and more sustainable results, as reflected in subsequent evaluation data.

McKeon added that elements of the GLS program required grantees to stretch. As an example, he cited the Early Identification Referral Form (ERIF), a tool introduced as part of the evaluation strategy to track whether

youth identified as at risk through screening or gatekeeper training actually received the care they needed. Implementing ERIF was not easy, he acknowledged, as many communities lacked systems for tracking follow-up care. Still, the program team believed it was worth the effort. They needed to do more than just gather information from gatekeepers for the purpose of evaluation in order to know what happened to the young people who had been identified as at risk.

These reflections on grant design underscore the evolving nature of program implementation and evaluation, as well as the need for continuous learning across the field. As McKeon noted, building and sustaining a national infrastructure for suicide prevention requires not only funding and strategy, but a community of practice committed to sharing progress and growing together. “When I started in suicide prevention in 2001 or 2002,” he recalled, “most of the people working in the field could fit in a single room and there would be plenty of space.” He contrasted that with the present-day reality, where national conferences regularly draw over a thousand attendees. “We have built a workforce and a community,” he said. “There is reason for hope, because many programs have shown forward progress and impact.” He emphasized the importance of continuing to learn from one another, noting that gatherings like the workshop offer essential opportunities to do just that.

Expert Insights on Program Development and Oversight and Grantee-Level Implementation and Performance Metrics

During the second panel discussion, the speakers who provided the foundational presentations summarized above were joined by Ebony Akinsanya (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] Foundation) and Christine Walrath (ICF) to discuss topics including encouraging applications and assessing application quality; criteria for determining participant eligibility; best practices for outreach and soliciting participation; and best practices for data collection, use, and infrastructure.

Encouraging Applications and Assessing Application Quality

Walsh invited panelists to reflect on ways to expand access to and awareness of grant funding and to encourage applications, particularly among organizations that may not traditionally apply or see themselves as part of the public health space. Akinsanya responded by noting that the CDC Foundation has administered a mini-grant program for the past seven years that provides evaluation, capacity building, and technical assistance to veteran-serving organizations. Participating organizations are required to implement interventions aligned with protective or risk-reducing strategies

identified in CDC’s Suicide Prevention Resource for Action. One lesson learned from the program is the importance of working with veteran-serving organizations to help them recognize their public health role and build their confidence to apply for funding. She noted that some organizations do not readily see themselves as candidates for suicide prevention work and that funders can help bridge that gap. “She emphasized that outreach and encouragement are essential, along with keeping application barriers low. For example, her organization has moved away from requesting demonstration of evaluation experience as part of the application process; this experience is no longer expected of applicants.

Crosby encouraged programs to think about outreach to organizations that might have veteran community connections but may not recognize their work as relevant to suicide prevention. Stout added that state veteran service agencies may also be good avenues for spreading the word about funding opportunities to more local networks, along with state suicide prevention leads, who are often connected with many community coalitions. She also called attention to the Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC) Best Practices Registry,4 which offers a valuable resource for identifying interventions that reflect a broader range of evidence and emphasize inclusivity, cultural relevance, and population diversity. Standley echoed the value of the SPRC Best Practices Registry as a resource.

In terms of assessing applicant quality, Farmer suggested programs may want to consider having different criteria for different types of applicants. For example, if a prospective grantee is proposing an activity that is a new idea for which there is not a lot of evidence, maybe that would be more of a research grant to help build that evidence. If a prospective grantee has limited capacity, programs may want to emulate Face the Fight’s approach and treat it as more of an implementation grant to help build that capacity. Grants to established organizations that have a lot more experience may be treated as expansion grants. In other words, Farmer continued, programs may want to have different criteria for applications that would be dependent on the goals and the capabilities of the organizations applying to the program.

Walrath added that programs need to consider that capacity building requires sufficient resource allocation to ensure grantees are adequately equipped for both implementation and participation in evaluation. She also encouraged programs to ensure that they are selecting grantees who are committed to participating in evaluation and data collection, as well as committed to using data to inform their own improvement over time.

Yanovitzky added that funders can play a more active role in expanding access by using a combination of “push and pull” strategies that leverage

___________________

relationships, partnerships, and existing networks. For example, grantees themselves can be engaged as trusted messengers to help bring new voices, particularly early-career scholars, into the field. This approach broadens the reach of funding opportunities and helps avoid insular “echo chambers,” he said. He emphasized that understanding the broader ecosystem of actors in suicide prevention and meeting potential applicants “where they are” can help build trust and spark interest among organizations that might not otherwise seek out funding. Yanovitzky pointed to a recent example in which the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation launched a rapid-response funding opportunity and asked established partners to disseminate the information through targeted, relationship-based channels to accelerate uptake. Funders, he concluded, should be more proactive and deliberate in how they share opportunities and engage prospective applicants.

Criteria for Determining Participant Eligibility

Walsh then turned the discussion to the individuals these programs are ultimately intended to serve. He asked panelists what criteria they would recommend for determining who should be eligible to participate in the community-based suicide prevention programs offered by grantees. Stout responded that, based on her experience serving on the planning committee and thinking deeply about community-based suicide prevention, overinclusion is generally appropriate for these types of programs. Using the example of the GLS program, which has a targeted age range for youth suicide prevention and also prioritizes groups at disproportionate risk, she emphasized the importance of casting a wide net. Drawing on the public health framework of universal, selective, and indicated interventions, she argued that upstream, strength-building programs should be designed to reach all individuals who are eligible under a given grant, not just those already known to be at elevated risk. Limiting participation to individuals already identified as at risk, she explained, may undercut the potential impact of community approaches. Referring to earlier points raised about upstream prevention, Stout stressed the evidence base supporting efforts to intervene early—“before individuals are at the edge of the waterfall”—because reaching people upstream is where community approaches are going to be most impactful. At the same time, she acknowledged the importance of also developing programming for populations known to be at higher risk and ensuring crisis supports are available for those in acute distress. This inclusive approach, she said, is distinct from the structure of a closed clinical system, which typically focuses on indicated populations already engaged in treatment.

Yanovitzky added that while public health typically relies on identified needs to inform program development and targeting—particularly when

groups are not being reached or are underengaged—he noted that readiness to change is also a critical factor. He explained that trying to engage individuals or groups who currently lack the capacity, motivation, or opportunity to act may be ineffective in the short term. Instead, focusing on those who are ready to take action can generate early momentum and produce a cascading or snowball effect, building broader engagement over time. In his experience, he said, striking a balance between need and readiness can help maximize near-term impact while setting the stage for long-term change.

Walsh concluded the discussion of the question of eligibility criteria by underscoring the importance of both assessing need and gauging readiness when determining program eligibility. He emphasized that effective community-based suicide prevention requires meeting individuals and communities where they are—both in terms of risk and readiness for change.

Best Practices for Outreach and Soliciting Participation

To continue the conversation around reaching those most likely to benefit from suicide prevention services, Walsh invited panelists to offer recommendations for how grantees can best disseminate information about their services and encourage participation. He invited them to reflect on strategies that have proven effective for building awareness and increasing engagement among the populations that grantees seek to serve.

Standley opened the discussion by emphasizing the importance of identifying trusted community members—both formal and informal leaders—who can help spread awareness. These individuals might include local business owners, parks and recreation staff, or shelter workers. He encouraged expanding traditional definitions of leadership and expertise to include those with lived experience, such as loss survivors, attempt survivors, or those deeply engaged in schools or other community systems. Building relationships with trusted community figures, Standley noted, can help generate a snowball effect that broadens the reach of outreach efforts.

Crosby echoed these points, highlighting the importance of identifying both formal and informal community leaders. He recalled a story about a senator who disclosed personal experience with suicide loss in a public setting for the first time, underscoring the potential influence of public figures who choose to speak out. Crosby also noted the importance of ensuring that community stakeholders and program participants receive information about the work being done, creating a feedback loop that helps generate buy-in and build goodwill.

Stout added that community engagement is a two-way street: it is not only about disseminating information but also about learning from others engaged in related work. She encouraged grantees to ask what community leaders and partners are already doing, how their efforts may align with

suicide prevention, and where there may be opportunities to support or build upon existing initiatives.

Yanovitzky emphasized that both communication and evaluation should be treated as integral to program planning and implementation, not afterthoughts. He urged grantees and funders to engage experts in communication and dissemination science early in the process and to build adequate funding into program budgets for these activities. Effective dissemination, he explained, requires careful planning, audience analysis, and clear strategies for engagement and message delivery. He noted that without this, programs risk missing the opportunity to communicate impact in ways that resonate and inspire action.

Akinsanya shared that, in the fourth year of her program, grantees were required to develop communication and dissemination plans. These were built on earlier efforts to create partner engagement plans and to understand the expectations of various stakeholders. She explained that effective dissemination requires tailoring findings to meet the needs of different audiences, and that grantees should be encouraged to share results publicly—through conference presentations, white papers, or other formats—regardless of whether they come from traditional academic backgrounds.

Farmer agreed, adding that the ability of an organization to engage its community should be considered during the grant application process. Programs should assess the degree to which applicants are embedded in and connected to the communities they propose to serve. If an applicant lacks that capacity, she said, funders should ensure that resources are provided to support meaningful community engagement. Without that connection, even well-intentioned efforts may fall flat or miss their intended audience.

Standley returned to the importance of evaluating the partnerships themselves. He noted that when programs fall short of expected outcomes, it may be because the partnerships underlying the work are not functioning optimally. Evaluating partnership processes—such as levels of trust, alignment on goals, and perceptions of sustainability—can help identify areas for improvement and ensure that partnerships remain strong and effective throughout and beyond the funding period.

Crosby closed the discussion by emphasizing the value of peer-to-peer learning among grantees. He observed that funders can help facilitate this exchange by convening grantees to share their strategies and experiences. In such settings, participants can learn from one another, adopt successful approaches, and strengthen their own community engagement efforts as a result.

Strengthening Data Capacity: Best Practices for Collection, Use, and Infrastructure

For the final question of the panel discussion, Walsh invited panelists to share best practices for supporting grantees in handling data, a central cross-cutting theme of the workshop. He asked them to reflect on topics such as identifying common data elements, using data repositories, and building capacity for meaningful use and interpretation.

Walrath opened the discussion by highlighting the value of common data elements across grant programs. She stressed that common data elements do not imply inflexibility, but rather a baseline that supports both local and cross-site evaluation while allowing room for additional, tailored measures. Walrath emphasized the importance of collecting and analyzing implementation data alongside outcomes, explaining that without a clear understanding of what was delivered and at what scale, impact is difficult to interpret. She also shared an example from the GLS program, which uses a centralized data repository that allows all grantees to enter and access data within a shared system. While such infrastructure requires resources, Walrath noted, it offers substantial benefits in terms of consistency, accessibility, and insight.

Crosby expanded on the idea of core data elements, drawing on examples from infectious disease reporting. He pointed to the CDC’s system for weekly notifiable disease surveillance, where each state is required to report on a core data set but may also choose to add context-specific elements, and underscored the value of applying a similar model in suicide prevention—balancing national consistency with local flexibility. Crosby also emphasized the need for community sensitivity in data collection and cited the importance of ensuring that underserved populations are adequately represented. As an example, he noted early gaps in COVID-19 race and ethnicity data that limited the ability to tailor effective interventions. He urged suicide prevention programs to collect complete and representative data to avoid similar blind spots.

Yanovitzky offered three additional considerations. First, he emphasized that data should be actionable; they must be collected and used in support of decision-making and learning. Second, he encouraged programs to expand their definition of impact to include broader elements such as capacity-building, and to engage stakeholders in shaping how that impact is defined and measured. Third, he underscored the opportunity to build data infrastructure across communities and programs. He shared that, in his own work, data repositories are a requirement of foundation-funded grants, and that universities can often support long-term public access. He advocated for open data platforms and cross-state collaboration, noting the potential to create valuable shared resources that do not currently exist at the federal level.

Akinsanya added that both qualitative and quantitative data should be recognized as important. In her program’s federally funded work, they often rely on qualitative data from grantees due to restrictions on other forms of data collection. Grantees have reported that their involvement in evaluation has strengthened community partnerships, increased program credibility, improved services for veterans, and enhanced organizational viability. These outcomes, she emphasized, reflect meaningful benefits that may not be captured through quantitative indicators alone.

Walrath returned to the conversation to emphasize two final points: first, that programs should avoid duplicative data collection by leveraging existing sources when available, and second, that data should only be collected if they will be used. She reiterated that limited resources should be focused on generating useful, actionable insights that inform practice.

Audience Q&A

Walsh offered audience members the opportunity to ask questions of participants from both panels. Topics raised by audience members included clarifying program goals to inform data collection, inclusion criteria for community-based programs, finding funding and collaborative partners, and supporting community engagement in the pre-award phase.

Clarifying Program Goals to Inform Data Collection

Tanha Patel (CDC Foundation) raised a point about the importance of clarifying a program’s intent before establishing data collection protocols. While much of the discussion had centered on common data elements, she emphasized that without a clear understanding of a funder’s goals, it is difficult to determine which data are meaningful. Stout agreed, suggesting that just as grantees are expected to develop logic models, funders should do the same. These models can help define expected short- and intermediate-term outcomes and guide evaluation planning. Farmer added that upfront alignment between data needs at the program and grantee levels can help reduce burden while ensuring data are useful for both local and aggregate evaluation. Yanovitzky echoed the importance of feedback loops in this process. Too often, he said, grantees are treated like contractors, with little opportunity to shape future research agendas. Instead, funders should systematically gather grantee insights—such as through “exit polling”—to inform future funding priorities.

Inclusion Criteria for Community-Based Programs

The conversation then turned to screening tools and eligibility criteria. Michelle Kuntz (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Suicide

Prevention) asked whether panelists had recommendations for identifying appropriate participants for upstream, non-clinical suicide prevention efforts. Stout emphasized the value of broad inclusion criteria, especially for veteran populations. While targeted screening tools may be appropriate in some cases, she cautioned that relying solely on clinical tools risks missing individuals who do not meet diagnostic thresholds but are still at risk. She added that from a public health perspective, overinclusion, especially for a veteran population, makes sense, noting that she would consider the whole veteran population as eligible for participation in community-based suicide prevention efforts. Askinaya agreed, stating that many at-risk veterans do not have clinical mental health diagnoses; instead, risk may stem from social factors like financial strain or relationship issues. Accordingly, her program does not impose strict screening requirements on grantees but does require demonstrated connections to the veteran community, she noted. Crosby encouraged attendees to think beyond veterans themselves, noting that family members—especially those who have experienced loss—may also face elevated risk and could be important targets for outreach and support.

Finding Funding and Collaborative Partners

Tina Winters (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine) noted that several virtual attendees—including one running a “vet café” in rural Oregon and others focused on peer support or combating isolation—were seeking guidance on where to find information about available funding and how to connect with potential collaborative partners. Jancaitis responded by acknowledging the challenge of identifying funding streams, particularly in the current climate of uncertainty. She suggested that state-level suicide prevention coalitions and the Governor’s Challenge to Prevent Suicide could be valuable resources, as both typically bring together federal, state, and local funders. “Just the speakers that have been featured here gives you a good idea of the toolbox,” she noted, encouraging participants to start by engaging with coalitions already active in their regions, even if they are not veteran specific.

Supporting Community Engagement in the Pre-Award Phase

Diana Clarke (American Psychiatric Association; member, workshop planning committee) posed a question to the panel related to funder flexibility and community engagement. She noted that while early engagement is critical for reaching the most vulnerable communities, those same communities often lack the time and resources to participate in program design before funding is secured. Clarke asked whether funders have considered

supporting applicants during the pre-application phase to facilitate authentic engagement, akin to a supported letter-of-intent process. Stout responded that some SAMHSA grants—particularly those related to substance misuse prevention—have built-in planning periods, often used to review data and establish local partnerships. She added that during the early phase of the Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grants, states convened epidemiological workgroups to analyze data and prioritize areas for action before sub-awarding funds to communities. While not a perfect model, Stout offered this as an example of how planning and community engagement can occur without locking grantees into a fixed proposal at the outset.

Clarke followed up with a concern that even in programs with a formal planning phase, applicants may feel constrained by what they initially proposed. If the community identifies different priorities during the planning phase, she asked, how much flexibility do grantees have to adjust course? Stout acknowledged the tension, but reiterated that in some funding models, communities are not required to pre-select specific issues prior to the planning phase. While the process is not entirely open-ended, she said, there is still room for alignment with evolving community input.

Rozek added that from the funder side, it is important to think flexibly. He described instances where Face the Fight grants were altered midstream in response to implementation challenges or a misalignment with the intended audience. “We could let this play out and say, ‘This is a contract and it’s going to fail,’” he said. “Or we could develop new KPIs [key performance indicators] and new targets and shift the grant.” This sometimes involved additional funding, he noted, but was necessary to ensure the work stayed relevant and impactful. Stressing that flexibility and innovation are key, Rozek emphasized the importance of compensating community members for their time and expertise when asked to contribute and being creative in working within rigid funding structures.

Walsh closed the session by thanking both panels and inviting attendees to continue the discussion throughout the remainder of the workshop.

REFERENCES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Suicide prevention resource for action: A compilation of the best available evidence. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/pdf/preventionresource.pdf

Crosby, A. E., Han, B., Ortega, L. A., Parks, S. E., & Gfroerer, J. (2011). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2008-2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, 60(13), 1–22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6013a1.htm

Curtin, S. C., & Hedegaard, H. (2019, June). Suicide rates for females and males by race and ethnicity: United States, 1999 and 2017. National Center for Health Statistics Health E-Stats. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/suicide/rates_1999_2017.pdf

Education Development Center. (2025). Community-led suicide prevention online toolkit. https://communitysuicideprevention.org/

Hedegaard, H., Curtin, S. C., & Warner, M. (2020). Increase in suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2018 (NCHS Data Brief No. 362) National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db362-h.pdf

National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. (2017). Transforming communities: Key elements for the implementation of comprehensive community-based suicide prevention. Education Development Center. https://theactionalliance.org/sites/default/files/transformingcommunitiespaper.pdf

Potter, L. B., Powell, K. E., & Kachur, S. P. (1995). Suicide prevention from a public health perspective. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 25(1), 82–91.

Ramchand, R., Senator, B., Davis, J. P., Hawkins, W., Jaycox, L. H., Lejeune, J., Livingston, W. S., Locker, A. R., Trachik, B., & Athey, A. (2025). Preventing veteran suicide: A landscape analysis of existing programs, their evidence, and what the next generation of programs may look like. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3635-1.html

Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2020a). Comprehensive approach to suicide prevention. https://sprc.org/effective-prevention/comprehensive-approach

___. (2020b). Strategic planning approach to suicide prevention. https://sprc.org/effective-prevention/strategic-planning/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2024). National strategy for suicide prevention. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/national-strategy-suicide-prevention.pdf

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2018). National strategy for preventing veteran suicide. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf

___. (2024). 2024 National veteran suicide prevention annual report, part 2 of 2: Report findings. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2024/2024-Annual-Report-Part-2-of-2_508.pdf

Wisconsin Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Moving prevention upstream. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p02695a.pdf

World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/131056