Disseminating In Silico and Computational Biological Research: Navigating Benefits and Risks: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 1 Context on In Silico Research and Biosecurity

1

Context on In Silico Research and Biosecurity

Committee co-chairs Valda Vinson, Science, and Alex John London, Carnegie Mellon University, offered welcoming remarks to set the stage for the workshop discussions. London described the workshop as residing at the intersection of in silico models and computational approaches, dissemination of research outputs and resources, and research benefits and biosecurity risks. He highlighted the now rescinded United States Government Policy for Oversight of Dual Use Research of Concern and Pathogens with Enhanced Pandemic Potential, issued May 6, 2024, as one context in which the importance of developing voluntary guidance for in silico models and computational approaches in biology has been raised in recent years

In framing the workshop’s aims, London distinguished between the conduct of research and its dissemination, emphasizing that the workshop was intended to focus on the latter. Although oversight mechanisms that govern the conduct of in silico research are relevant, given their potential influence on how research is ultimately shared, the workshop’s primary goal was to elicit discussions and suggestions specifically on dissemination practices. Publishing in scientific journals remains an important mechanism for sharing scientific findings, but, as London also noted, in silico research dissemination, particularly involving AI and computational modeling, can yield a wide range of outputs (see Figure 2a) that may be shared through various outlets (see Figure 2b).

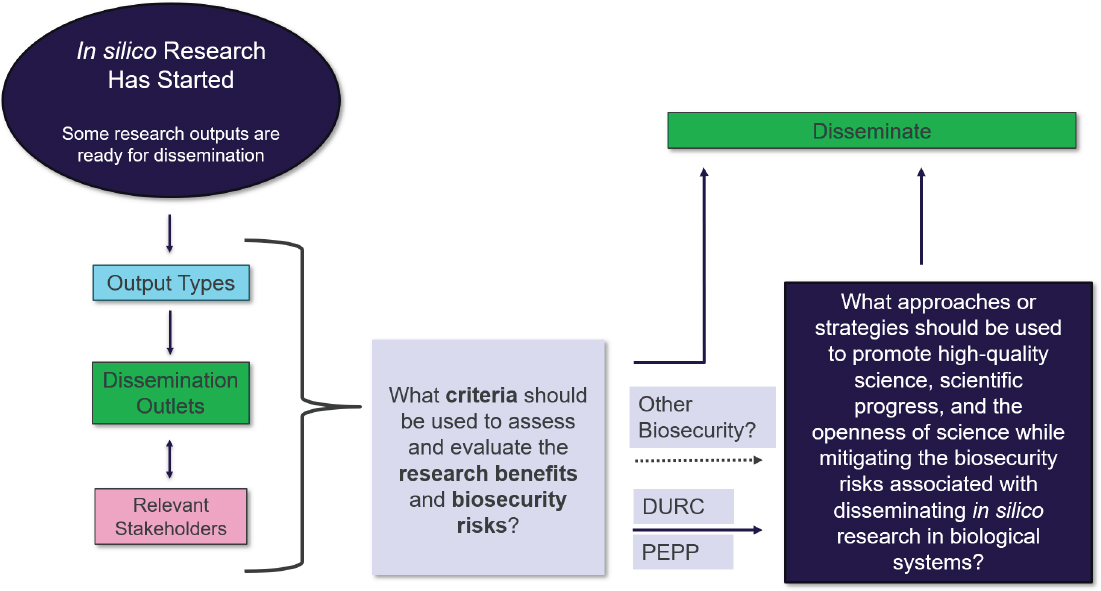

As such, London said that the workshop focused on dissemination broadly, which refers to the sharing of research outputs beyond traditional peer-reviewed publications. This includes preprints, software and code repositories, online platforms (e.g., GitHub, Hugging Face), data sharing portals, API access, conference presentations, blogs, and social media communications. Dissemination encompasses any method by which the outputs of in silico biological research (e.g., models, tools, datasets, sequences) are made available to others, intentionally or unintentionally. The diversity of both outputs and outlets is captured in Figures 2a and 2b, which categorize and illustrate the multifaceted nature of dissemination in this field. London also refers as “stakeholders” those who are responsible for safeguarding the benefits of such research while mitigating and managing the associated risks. Against this backdrop, he highlighted two key questions: (1) What criteria should be used to assess and evaluate the research benefits and biosecurity risks?; and (2) What approaches or strategies should be used to promote high-quality science, scientific progress, and the openness of science while mitigating the biosecurity risks associated with disseminating in silico research in biological systems? This framing is illustrated in Figure 3.

Three workshop sessions provided context on these questions by examining current considerations around the benefits and biosecurity risks of in silico biological research, lessons from past biotechnology governance, and lessons from other domains.

STATE OF KNOWLEDGE ON THE BENEFITS AND BIOSECURITY RISKS OF IN SILICO BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH

London moderated an opening session focused on the current state of knowledge regarding the benefits and potential biosecurity risks associated with disseminating results and resources related to in silico biological research. The panelists were Gigi Gronvall, Johns Hopkins University; Lynda Stuart, Fund for Science and Technology; Sara Del Valle, Los Alamos National Laboratory; Feilim Mac Gabhann, Johns Hopkins University and PLOS Computational Biology; and Valda Vinson, Science.

Biosecurity History and Current Context

Gronvall offered a brief review of the historical context of security issues related to research and the different perspectives about and approaches to dissemination that have emerged in response. Highlighting three events that have informed thinking about these issues over the past several decades in the United States and internationally, she described the tension between the clear benefits of advancing scientific research to support health and safety and the potential for misuse of scientific knowledge to cause harm and threaten national security.

The first event occurred during the Cold War, when concerns were raised about the dissemination of research that could aid the Soviet Union in its missile-building program. In response, a National Academies committee weighed the benefits and risks of wide dissemination of physics research and concluded that security by openly demonstrated scientific achievement was preferable to security by secrecy, even in the context of nuclear weapons (Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, and National Academy of Engineering, 1982). The second event occurred in the wake of a series of attacks in which anthrax was delivered by mail shortly after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. After those events, a National Academies committee published

a report that considered the security risks associated with biological research and identified seven activities of concern that could lower the barriers to the development of biological weapons (National Research Council, 2004). This study led to the U.S. government establishing the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB)1 whose mission is to advise the government on biosecurity issues. In addition, scientific journal publishers started to collaborate on the development of strategies for the responsible dissemination of research with potential dual-use concerns (“Statement on Scientific Publication and Security,” 2003). The third event occurred during the early 2010s, when researchers identified specific genetic mutations that could allow transmission of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses (H5 viruses) between mammals through the air (called “gain-of-function” research), sparking a controversy over whether publishing such research could provide a blueprint for malicious actors to develop a biological weapon and whether a voluntary moratorium should be considered (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015).2 Gronvall emphasized that sharing research findings is critical to advancing scientific knowledge. Although sharing research only with those who have legitimate purposes and not with those who intend to use it for harm is ideal, she cautioned that it is extremely difficult to do in practice. She added that risks are inherent in any restriction of research dissemination. For example, withholding knowledge about influenza viruses impedes research that could become important in fighting the next pandemic. She pointed to knowledge gaps around the H5N1 influenza virus that is currently circulating in birds, cows, and other animals as an example. “The fact that we do not know more about this pandemic threat is tied to the fact that it’s been so hard to do research in this area,” Gronvall said. “So, there is a cost to being able to put barriers toward a legitimate scientific inquiry.”

Finally, Gronvall said that recognizing the limits of isolated mitigation strategies is vital. Stopping the conduct or dissemination of certain types of research in the United States will not be sufficient to prevent the next pandemic from occurring or a bioweapon from being developed. Even if malicious actors are prevented from pursuing dangerous work here, such work could still be done elsewhere. Therefore, Gronvall said investing in the United States’ research that can support the nation’s preparedness and response capabilities remains important.

AI in Biological Design

Stuart discussed recent developments and considerations around the application of AI in biological prediction, analysis, and design. A recent National Academies study, The Age of AI in the Life Sciences, for which Stuart served as co-chair, provides a resource for examining how advances in AI have been applied to life sciences in synergistic and amplifying ways (NASEM, 2025). The report identifies several areas where this convergence between AI and life sciences can enable and accelerate promising applications such as drug discovery, precision medicine, environmental remediation, and synthetic biology. With a focus on synthetic biology (an area particularly relevant to biosecurity), Figure 4 highlights three parts of the engineering process where AI tools can help accelerate progress.

Stuart said that, overall, the greatest impact of AI in terms of boosting biodesign capabilities is currently seen in the ideation phase, where AI-enabled biological tools enable scientists to easily and quickly generate a vast number of hypotheses, which can then be refined and tested. She noted that such hypotheses are not inherently dangerous. “Those designs are really just generating hypotheses that are on a computer […] only when they are transferred into the physical world would you really have to worry about them as being biological agents,” she said. In fact, this hypothesis generation approach can help to protect public health and national

___________________

1 See https://osp.od.nih.gov/policies/national-science-advisory-board-for-biosecurity-nsabb/ (accessed June 24, 2025).

2 See https://www.science.org/content/article/us-halts-funding-new-risky-virus-studies-calls-voluntary-moratorium (accessed July 14, 1025).

SOURCE: NASEM, 2025.

security by accelerating the response to emerging microbial threats, whatever their origin. Stuart also noted that large amounts of high-quality biological data are crucial for training models and enabling innovation, and that the ultimate impact of computational capabilities will be limited by the availability of such data, the biological complexity of the tasks, and the need for experimental validation. For example, AI-enabled molecule design tools are very powerful because of the simplicity of the task and the abundance of data; however, AI-enabled biological tools cannot complete complex experimental tasks, such as making a highly transmissible virus, because these data are lacking.

Stuart pointed to studies involving the design of novel protein structures, such as that conducted by Nobel Laureate David Baker, University of Washington. Multiple powerful in silico models have been developed in the area of protein design, including tools generating new protein structures (RFDiffusion) (Watson et al., 2023), assigning amino acids to desired protein structures (ProteinMPNN) (Dauparas et al., 2022), and predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences (RoseTTAFold) (Baek et al., 2021). These tools, enabled by AI algorithms trained on vast amounts of data, create hypotheses that are carefully filtered before being tested in wet labs. Ultimately, these approaches can enable the design of new peptides, minibinders (small protein binding molecules), vaccine designs, and antibodies. Stuart noted that such capabilities can not only advance fundamental knowledge but also be applied to rapidly aid in developing medical countermeasures to biological threats, such as biologics and vaccines. “It’s actually really important to appreciate that it really is almost out of the ether that you can now generate something that could block an antibody, for instance,” Stuart stated. “That power really speaks to how much this benefits countermeasure development.”

In considering implications for weaponizing AI-enabled biological tools in synthetic biology, she posited that the need to filter designs and perform wet lab experimentation and validation likely limit the risks currently. Although she believes that the benefits currently outweigh the risks, she acknowledged that the wide availability

and extremely promising design capabilities of AI tools warrant close attention and monitoring by the scientific community going forward. As discussed in the NASEM (2025) report, an if-then framing (e.g., a participant shared, if a model enables the design of a novel pathogen with high fidelity, then initiate an expert review before publication) could be helpful in monitoring new advances to inform risk assessment. Similarly, Stuart suggested that an if-then approach could be useful for evaluating what to publish (or not) based on a consideration of the design’s proposed function and how easily and accurately the physical product can be created in a wet lab.

Opportunities, Risks, and Responsibilities in the Dissemination of Computational Models

Del Valle discussed how AI and computational biology advances present new challenges for established biosecurity guidelines and practices in scientific publishing, highlighting a particular computational technique known as agent-based models (ABMs) as a case study. Framing her remarks, she emphasized that the scientific community is at a critical juncture. “We’re at a time where powerful biological designs and threats may not come from nature, but from code,” Del Valle said. “Whether it’s predicting outbreaks or generating entire genomes, there’s a shift toward in silico biological research, and so we need to understand the risk.”

ABMs are based on the fact that complex global behaviors can emerge from the interactions of many simple rule-based agents. In AI-powered ABMs, agents interact in realistic environments governed by rules and decision-making processes while learning and adapting, enabling them to model highly complex behaviors. One example is EpiCast, a simulation tool created by researchers at Los Alamos National Laboratory to model respiratory disease transmission to inform pandemic preparedness and response. Del Valle stressed that these are not just theoretical tools. EpiCast and other ABMs have been applied to inform decision-making in situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic and have real-world implications. For example, they have been used to identify transmission paths, simulate intervention failures, and characterize outcome distributions. However, these capabilities also create the potential for misuse, especially because most journals require researchers to release their models or code along with the research results.

Regarding the responsible dissemination of such work, Del Valle said that it is important to consider (1) whether the research enables capabilities that could be used for harm, (2) whether the model could be exploited easily or enhanced without specialized knowledge, or (3) whether the model could inform or inspire malicious actors. To support more anticipatory risk assessment, Del Valle proposed a spectrum of threat types, from linear to discontinuous (Figure 5), as a conceptual tool rather than a strict rubric for dissemination decisions. Here, risks may evolve unpredictably over time, underscoring the need to evaluate not only immediate concerns but also how dissemination could enable more complex or unforeseen risks in the future.

The framework that regulates nuclear activities is a helpful model for safe research dissemination. It includes preventing proliferation, monitoring and verifying, reducing global risks, controlling nuclear trade, and banning nuclear testing. Del Valle posited that efforts to address dual-use concerns in the age of AI can benefit from a framework that has the same essential attributes of being well-structured, appropriately resourced, and global. “The tools to simulate biology are outpacing the norms for sharing it, so it’s time to rethink how we assess risk,” she said. “We need to preserve openness without enabling risk, and that’s what we need in a new framework […] we can calibrate this for computational models and ground them in lessons from other domains such as nuclear science.”

Benefits and Risks of Publication

Focusing on the lens of scientific publication, Mac Gabhann and Vinson presented an overview of some of the benefits and risks of broad research dissemination. Mac Gabhann noted that openness has long been a core tenet of the computational science culture, with 98 percent of studies published in scientific journals sharing

code. This norm is not confined to computational biology. An emphasis on openness exists in other areas of science. Sharing results and the underlying data and code enables accessibility, transparency, and reproducibility. Equally important, Mac Gabhann noted, open science advances progress. “Progress in science often builds on the work of others, and open sharing and dissemination really increases the ability for other scientists to use, to extend, to enhance, build on the materials, and it advances science even further,” Mac Gabhann said. “This inspires new directions.”

Although scientific journal publishers typically expect authors to publish their data and code, they allow exceptions when doing so would present risks. Vinson outlined three main categories of exceptions:

- Claims of intellectual property protection: Vinson noted this claim is often not accepted as sufficient justification. In fact, generally, the data are made available even if the code is protected as proprietary.

- Data with privacy concerns: This category includes personally identifiable clinical data or ecological data that could threaten endangered species. Here, data may need to be anonymized or have location details withheld.

- Biosecurity implications, specifically DURC or PEPP. Cases in this category are typically handled on an individual basis.

In borderline situations, editors typically consult with multiple experts to determine whether research should be published or not. Vinson suggested the need for a better approach, noting that “as journals, we don’t really have a good general solution.”

SOURCE: Sara Del Valle, Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Discussion

Panelists discussed approaches to determining thresholds for dual-use concern, the relationship between in silico work and wet lab experimentation, and placement of current capabilities within the range of biosecurity threats that may be envisioned.

Conceptual Approaches to Understanding Risk

To inform approaches to identifying DURC in the in silico space—and potential opportunities to reduce risk—one question to answer is how to determine when dual-use potential becomes a real concern. On this point, Gronvall said that creating a broadly applicable approach to identifying this threshold is challenging, which is why a case-by-case approach has generally prevailed. This assessment is complicated because predicting the performance of a design in the wet lab or the ways that a malicious actor could apply the research is nearly impossible.

Another question centers on identifying the mitigation strategies that could be applied to the dissemination of training data, model validation, or other aspects of the computational science process to reduce biosecurity risks that might arise from in silico research. Stuart suggested the strategy of releasing a model but deliberately withholding certain data. However, as a downside, this approach renders the model less useful for beneficial applications (such as creating countermeasures). In addition, this approach is also unlikely to thwart actors with true malicious intent because they could use a different data set to retrain the model, calling into question both its practicality and effectiveness.

Responding to a question on how novel the quick timelines and approaches for tackling AI-related progress are compared to other linear, exponential, iterative, and discontinuous risks, Del Valle explained that the types of problems we face have long existed in other domains, such as in mathematical models, where stable systems can quickly shift into chaotic behavior. She said that a proactive, rather than a reactive, approach to implementing safeguards against AI-related risks is likely a stronger strategy at this time, because of the inherent unpredictability and wide range of spaces that AI affects.

Practical Considerations in the Context of Current Capabilities

In response to a question about whether the capabilities exist, either in silico or in wet labs, to design viruses that are more lethal, Gronvall stated that many knowledge gaps limit the capacity to predict or produce a new lethal virus, despite the increased understanding of viruses over the past several decades. Stuart added that the design of toxins, although perhaps more technically feasible, remains challenging and requires extensive experimentation and high-quality training data. Although the current amount and quality of the data available limit the capacity for de novo development, she said that models will undoubtedly improve as more data are generated and shared, underscoring the importance of continuous monitoring of emerging models and data for signals that these capabilities may be becoming closer to reality.

According to Roger Brent, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, AI models are rapidly becoming more capable in terms of designing, building, and testing hypotheses. In particular, he said that large language models (LLMs) have proven to be especially valuable tools for both in silico and wet lab experimentation. He also noted that a design tool does not have to be 100 percent accurate to be effective. Stuart agreed, noting that design capabilities are less important than the capability to effectively filter candidate designs, because strong filters will reduce the amount of wet lab experimentation required. She added that although the use of AI tools in wet labs will increase, they will not fully replace wet labs, reiterating that the threat posed by a malicious actor is much more limited in the absence of a wet lab. Gronvall added that the host response is also an important part of

pathogenicity. For example, H5N1 influenza virus appears to be more lethal in cats than in humans. Because host responses to novel viruses are often unknown and because this information is difficult to obtain in existing datasets, they are difficult to model by current AI tools such as LLMs.

In response to a question from a participant about the relationship between in silico and wet lab capabilities, Stuart noted that some research organizations have recently started to advance these different approaches in tandem, with an increasing number of computational labs adding on-site wet labs. She posited that wet labs will increasingly adopt in silico tools as they become easier to use. For now, actors rarely have the capability to both generate and synthesize a protein sequence; however, as tools become more accessible, this design-synthesis coupling may become more common.

A participant asked whether identification of the malicious actor would inform decision-making about dissemination. Gronvall replied that potential adversaries could be individuals or states and emphasized the importance of considering their available resources, potential barriers, required equipment, and motivation. Mac Gabhann added that knowing the identity(ies) of the potential actors could help to inform a theory about why a concern may exist. Vinson replied that scientific publishers are not the best suited to identify potential actors, but geopolitics can inform their selection of reviewers to avoid sharing DURC with people who could be connected with adversarial states.

LESSONS FROM ESTABLISHED GOVERNANCE

The concerns and challenges raised in the context of AI and other recent computational developments are only the latest in a long history of concerns and challenges stemming from biotechnology advances. Amina Ann Qutub, The University of Texas at San Antonio, moderated a session examining lessons that can be drawn from historical and current efforts by scientists, policymakers, and other experts to navigate risks and opportunities in data sharing, model accessibility, and governance for established biotechnologies. Panelists, featuring Diane DiEuliis, National Defense University, and Kenneth Oye, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, discussed how safeguards can be leveraged effectively to promote responsible innovation without unduly hindering scientific progress.

Although the workshop focused on dissemination, many participants emphasized that decisions about whether, and how, to disseminate in silico biological research are often influenced by upstream factors. These include whether the research should be conducted at all, how it is funded, and whether appropriate ethical or risk assessments are performed at the proposal stage. To clarify this relationship, the participants distinguished two phases of risk governance (1) upstream oversight involving decisions made before or during the conduct of research, such as risk-based funding decisions, project design, institutional oversight, and risk–benefit analysis, and (2) downstream dissemination involving decisions about sharing completed research outputs (e.g., what to share, with whom, and through which mechanisms), while considering both risks and benefits. While these stages are distinct, they are also interdependent. The discussions highlighted that upstream practices may reduce downstream dissemination risks.

A Historical Context on Current Challenges

Rather than proactively considering risks and building structures to address them, DiEuliis said that policy and governance around biosecurity issues have generally been iterative and reactive, with adjustments or the creation of new policies made in response to events. This approach errs on the side of openness to support innovation and has led to a broad approach in which multiple roadblocks are established at different points to deter, but not fully prevent, bad actors from using biology for malicious purposes. “I have likened this to creating many small hurdles to the harmful use of biotechnology—that is, ‘death by a thousand paper cuts’ to a poten-

tially bad actor,” said DiEuliis. She noted that, although imperfect, this approach to disruptive technologies has been successful in the past and has led to important measures, such as biosecurity reviews, that have increased awareness of the risks associated with the publication of certain types of information. In other words, a bad actor may conclude, “There’s too many things I have to traverse to try and use biology for crime, so, I’m just not going to.”

The current moment poses new and challenging questions because bioscience is advancing faster than policies, norms, and best practices can be developed to respond to them. In silico research can be disseminated broadly and rapidly, and any data or models that are publicly available will be accessible to people and AI models. Setting a firm threshold for DURC in the life sciences is extremely challenging, DiEuliis noted. She emphasized the value of fully defining the outcomes to be prevented and the actors involved in those outcomes and then working backward to determine if-then statements that elucidate the inflection points where information or capabilities become dangerous. She also highlighted the need to understand which policy tools can be applied at those points and what kinds of data or models are actually accessible to different types of actors.

The Value of Engagement

Oye shared several examples that illustrate how engagement and collaboration among researchers, journal editors, policymakers, and other experts can support the responsible dissemination of research to simultaneously preserve research benefits, address security risks, and support innovation. In the first example, researchers submitted their work on CRISPR-enabled gene drives to Barbara Jasny, the then editor of Science, who had concerns about its potential implications but lacked a specific policy to guide her decision-making. Jasny sought input from multiple experts, including federal law enforcement, and opted to limit the information published to minimize biosecurity risks. In another example, Nature editor Véronique Gebala carefully considered the risks of sharing work on opiate synthesis in yeast and ultimately decided not to limit dissemination. In the third example, Oye and a diverse group of biology and biotechnology experts used a collaborative process to inform research priorities on areas of uncertainty surrounding synthetic biology for the National Science Foundation (NSF). In each example, Oye said that a key lesson was the value of personal engagement and trust-building when drawing upon a range of expertise to consider benefits and risks. “Attentive and responsible editors engaging with authors and jointly trying to figure out what makes sense is not a bad way of doing it, assuming that the editors and the authors are trustworthy,” he said.

Oye shared that while journals have different resources and priorities, the editors he knows are vigilant about the issues under discussion here. In addition, no one knows everything, and therefore, as new technologies emerge, scientists need access information to understand the technology and effectively evaluate potential harms. “The problem is that if you restrict knowledge, you’re also restricting access to the information that the editors need to be responsible, or biosafety officers need to be responsible. So, it’s a bit of a conundrum,” he noted.

Lessons from Effective Frameworks and Policies

Qutub asked panelists to comment on the policies that have been most effective in designing safeguards or evaluating security risks. DiEuliis highlighted the Framework for Nucleic Acid Synthesis Screening (2024). This framework was developed in response to a red teaming article on one DNA synthesis company when very few existed, and it plays a critical security role by providing screening guidelines for the hundreds of DNA synthesis companies that now exist globally. She noted that this framework could serve as a model for addressing AI capabilities in the biosciences. Oye stressed the importance of using simulated attacks, or red teaming, to identify security risks and gaps. He noted that a multinational consortium involving China, Europe, and the

United States has been formed to screen for novel biological sequences, not just the usual known ones. The effort is designed to manage information hazards by encrypting and segmenting sensitive sequence data, ensuring that no single party has full access. He also mentioned government-led groups, such as the National Institutes of Health Novel and Exceptional Technology and Research Advisory Committee,3 that conduct reviews and long-range scanning for emerging technology concerns.

DiEuliis posited that the practice of red teaming has been very helpful in finding vulnerabilities in cybersecurity and could be done more regularly in the biotechnology sphere. However, red teaming is an expensive and time-consuming process. She suggested that the development of proxy tools, akin to viral compliance software, could help to reduce the barriers to and cost of red teaming. She also noted that cybersecurity provides a good model of international cooperation, particularly through agreements in the financial sector, because countries have been willing to coordinate on shared risks and standards. Such a framework could similarly support the safe development and oversight of in silico research.

Leveraging AI for Security and Global Data Governance

Although AI’s broad access to online information poses security risks, Oye noted that AI could be leveraged to help address them. For example, AI techniques could be used to limit access to sensitive data to a limited group, supporting a need-to-know framework for restricting access to information with the potential for misuse. “AI might, ironically, have a potential benefit in terms of addressing the problems that we face,” Oye stated. “AI might be able to discriminate, differentiate, allow you to narrowcast and target individuals that need the information.”

Qutub asked how multiple countries could collaborate on designing standards for training AI models on large genetic datasets. Oye replied that LLMs need large data sets that combine genetic and clinical information, but the challenges lie in determining who owns that data, what privacy considerations are involved, and how the data can be accessed and integrated effectively to be useful. The security and privacy standards of different countries and communities vary substantially, which runs counter to the effective use of the data. However, Oye suggested learning from approaches to cybersecurity in different contexts, such as utilities, banking, national security, and social media, to inform differentiated standards based on the level of risks for each context.

LESSONS FROM OTHER DOMAINS

Richard Sever, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, moderated a session exploring how in silico modeling, foundation models, and principles and practices for computational tools and generative AI safety could be informed by biosecurity efforts and security in other technological domains. The panelists—Steinn Sigurðsson, Pennsylvania State University and arXiv, Sean Ekins, Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, and Nandi Leslie, RTX Corporation—discussed policies, norms, and best practices established to facilitate the dissemination of information beyond DURC and PEPP.

Lessons from Publication in Open-Access Online Archive

ArXiv is an open-access online preprint server that mainly publishes research in the fields of physics, mathematics, computer science, and AI. In contrast to traditional scientific publishing, the approximately 20,000

___________________

3 See https://osp.od.nih.gov/policies/novel-and-exceptional-technology-and-research-advisory-committee-nextrac (accessed June 24, 2025).

papers that arXiv receives each month are not peer reviewed and are immediately published and made freely available. Later, authors usually submit their preprints to peer-reviewed journals for formal publication. The goal of this approach, Sigurðsson said, is “to speed up research, to accelerate the circulation of information, and get synergistic effects.”

Sigurðsson reflected on the lessons that arXiv editors have learned about the complexities of open scientific sharing, highlighting both its advantages and challenges. He began with a story that illustrates how scientific knowledge and capabilities evolve and how the process of correcting past errors can vary depending on the technological and historical context. In this example, researchers applied a calculation known as the “astronomers’ correction” to a large data set and then, decades later, quietly updated (i.e., without public attention), once advances in computational resources made it easier to reproduce and verify the original work. “The reason it was published, and the error correction was made, is because it went from being a hard problem to being a trivial problem, because computational capabilities improved,” said Sigurðsson.

In the context of arXiv, the practice of unfettered information sharing and free access has taught open-access online preprint editors some valuable lessons. First, once information is published online, it is instantly discoverable, copied, archived, and accessible to AI. Although arXiv sometimes will correct, revise, or remove data, “the content is forever,” Sigurðsson stated. A second lesson is that removal or alteration of content after publication, especially for security or misuse concerns, can have the unintended effect of drawing attention to that content and prompting questions about the reasons for its removal or alteration. As a result, it may sometimes be safer to leave such content accessible rather than removing it if it poses a risk of misuse. Finally, Sigurðsson noted that although arXiv employs AI to identify research that could be concerning, it is likely not as well-resourced as the large teams that may be searching for vulnerabilities to exploit.

Lessons from Ethics and Dual-Use Concerns in AI-Powered Drug Discovery

Ekins shared a story from his own experience that underscores gaps in ethics training and oversight related to dual-use research with AI in chemical design (Urbina et al., 2022). For a conference presentation, Ekins and colleagues applied their company’s AI model, originally developed for drug discovery, to design molecules with similar properties to known toxins such as VX, a chemical weapon. This red-teaming exercise, based on publicly available data, was later described in a scientific article. Despite initial reviews and censorship efforts, the article was unintentionally published online and was available for a month as open-access, resulting in widespread attention from government agencies, the media, and the public. Ekins noted he had no formal training in dual-use issues, there was no benefit-risk assessment, and no oversight mechanisms, since he ran his own company. He was later contacted by individuals seeking to use the technology for malicious purposes, including the design of chemical weapons, which he refused.

Following this experience, the co-authors wrote a follow-up paper with recommendations for avoiding unintentional conduct and dissemination of research with dual-use potential (Urbina et al., 2023). Their suggestions included familiarizing oneself with ethical guidelines, engaging multiple ethics and AI experts for research guidance, increasing training for scientists and students in ethics and dual-use concerns, and embracing oversight, including self-oversight. “I’d never had an experience of dual use before at all, I’m afraid; never had any training about it,” Ekins said. “I had no oversight. I own my own company, so I am the oversight. Didn’t do any benefit-risk assessment […] didn’t have any risk mitigation plan. I got myself into a bit of hot water.” Reflecting on the experience, Ekins admitted he would likely not have published the initial work had he foreseen the consequences.

Lessons from the Strengths and Limitations of AI Approaches in Cybersecurity

Leslie highlighted the challenges and opportunities related to the use of AI and machine learning (ML) in cybersecurity, providing some context for how these approaches might be leveraged to address concerns about in silico biological studies. In cybersecurity, “signatures” refer to identifiable patterns or known characteristics of malicious activity. Although signature-based detection has been widely used, its ability to detect novel or “zero-day” attacks that have no known patterns is limited. To address this gap, computational methods such as anomaly detection have been developed to identify unusual behavior that may indicate an attack. However, Leslie noted that signatures are still favored over anomaly detection in cybersecurity, in part because anomaly detection tends to generate high rates of false positives. AI and ML can help to overcome some of these issues. In the case of in silico biological studies, which are starting to use modeling, simulations, red teaming, and other cybersecurity practices to find vulnerabilities or simulate attacks, these techniques can help to clean data, fill data gaps, and ensure that quality data are not missing.

Leslie cautioned that the use of AI and ML is not without challenges. Researchers require a deep understanding of the techniques and systems being employed to know which algorithm to implement, follow relevant privacy requirements and laws, and be aware of the potential for adversarial attacks on the AI itself that can compromise data or create false negatives.

Finally, Leslie noted two distinct potential areas of ML that could be applicable to in silico biological research. The first is unsupervised learning, which can help to process large volumes of unlabeled data to better understand, categorize, and predict clusters in multidimensional feature spaces. This approach can be useful for uncovering patterns and structures within complex biological datasets. The second area is MLOps, in which developers (Dev) and operations (Ops) collaborate on ML to leverage automation and autonomy and improve the Development, Security, and Operations (DevSecOps) pipeline, where software is developed with security fully integrated into its entire lifecycle, from design through deployment. This approach promotes collaboration and resilience in ML workflows.

Feasibility of Restricting Access to Information

Sever asked the panelists to comment on whether controlling access to sensitive information can be a feasible approach. Sigurðsson replied that although this approach has been used for decades in various contexts, it runs counter to the general drive toward openness in science. He acknowledged that such restrictions are sometimes necessary but argued they are usually futile because scientific and technological development is accelerating so rapidly that restrictions tend only to delay, not prevent, the spread or use of information. Ekins added that work intended for one purpose can be applied in another, unintended domain. For example, results from drug discovery can sometimes veer unexpectedly into harmful applications, noting that the knowledge, once shared, cannot be “put back into the box,” and acknowledging that the work may have crossed a line once it was made public. Leslie stated that classification levels are appropriate in some cases. However, they must be applied judiciously so that the wider community can still find errors in models and data, make improvements, and advance science. “There’s a trade-off between classifying models, data, analyses, and making it open-access,” Leslie stated. “And that trade-off needs to be balanced and well understood per problem. There’s not one blanket solution for that.”