Mechanistic-Empirical Pavement Design Model: Enhancements of Climatic Inputs (2025)

Chapter: 3 Interpretations and Applications

CHAPTER 3

Interpretations and Applications

The enhancements developed to address the limitations identified in Chapter 2 are discussed in detail in this chapter, which includes the following major sections:

- Improving and Simplifying the Climate Input Parameters for Pavement ME

- Developing Enhancements of Climatic Inputs and Related Models for Future Incorporation in Pavement ME Design

- Validating New or Enhanced Models

- Identifying Enhancements to Improve EICM Functionality and Maintainability

3.1 Improving and Simplifying the Climate Input Parameters for Pavement ME

The LTPP InfoPave Climate Tool only includes a subset of the complete MERRA-2 dataset. The objectives of this task are to identify the MERRA-2 variables not included in the LTPP InfoPave Climate Tool that may be applicable for pavement applications, extract a representative subset for extensive testing, and provide recommendations on which variables to include that can simplify or enhance the EICM predictions. This section is structured as follows:

- A listing of available MERRA-2 data tables applicable to pavements

- A summary of MERRA-2 data extraction and unit conversions

- A selected set of comparisons and final variable selections

- A proposed process to integrate selected variables into the LTPP InfoPave Climate Tool

3.1.1 Available MERRA-2 Data Tables and Variables for Pavement Applications

The MERRA-2 NASA data tables with hourly data for potential use in pavement applications include the radiation diagnostics (tavg1_2d_rad_Nx), land surface diagnostics (tavg1_2d_lnd_ Nx), vertically integrated diagnostics (tavg1_2d_int_Nx), surface flux diagnostics (tavg1_2d_ flx_Nx), single-level diagnostics (inst1_2d_asm_Nx), and constant land–surface parameters (const_2d_lnd_Nx) tables (12). The shortlisted variables, which may have pavement applications, are summarized in Tables 2 through 6. It should be noted that in Table 2, the SPEED and SPEEDMAX descriptions are identical while their names are different. The MERRA-2 documentation does not specify a difference while it is suspected that the SPEEDMAX represents the maximum hourly wind speed.

Table 2. List of surface flux diagnostics (tavg1_2d_flx_Nx) variables for potential pavement applications.

| Name | Description | Units (SI) | U.S. Equivalent Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRECSNO | Snowfall | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 |

| PRECTOT | Total precipitation from atmospheric model physics | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 |

| PRECTOTCORR | Bias corrected total precipitation | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 |

| RHOA | Air density at surface | kg m–3 | lb ft–3 |

| TLML | Surface air temperature | K | K |

| ULML | Surface eastward wind | m s–1 | mi h–1 |

| VLML | Surface northward wind | m s–1 | mi h–1 |

| EFLUX | Total latent energy flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SPEED | Surface wind speed | m s–1 | mi h–1 |

| SPEEDMAX | Surface wind speed | m s–1 | mi h–1 |

Table 3. List of land surface diagnostics (tavg1_2d_lnd_Nx) variables for potential pavement applications.

| Name | Description | Units (SI) | U.S. Equivalent Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| EVLAND | Evaporation land | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 |

| EVPTRNS | Transpiration energy flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWLAND | Net longwave land | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| QINFIL | Soil water infiltration rate | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 |

| RUNOFF | Overland runoff, including throughflow | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 |

| SMLAND | Snowmelt flux land | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 |

| SWLAND | Net shortwave land | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| TSAT | Surface temperature of saturated zone | K | K |

| TSOIL1 | Soil temperatures layer 1 | K | K |

| TSOIL2 | Soil temperatures layer 2 | K | K |

| TSOIL3 | Soil temperatures layer 3 | K | K |

| TSOIL4 | Soil temperatures layer 4 | K | K |

| TSOIL5 | Soil temperatures layer 5 | K | K |

| TSOIL6 | Soil temperatures layer 6 | K | K |

| TUNST | Surface temperature of unsaturated zone | K | K |

| ECHANGE | Rate of change of total land energy | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| GHLAND | Ground heating land | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LHLAND | Latent heat flux land | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| PRECTOTLAND | Total precipitation land; bias corrected | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 |

| SHLAND | Sensible heat flux land | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SPLAND | Rate of spurious land energy source | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SPSNOW | Rate of spurious snow energy | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| TPSNOW | Surface temperature of snow | K | K |

| TSURF | Surface temperature of land, including snow | K | K |

Table 4. List of constant land–surface parameters (const_2d_lnd_Nx) variables for potential pavement applications.

| Name | Description | Units (SI) | U.S. Equivalent Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| dzgt1 | Thickness of soil layer associated with TSOIL1 | m | ft or in |

| dzgt2 | Thickness of soil layer associated with TSOIL2 | m | ft or in |

| dzgt3 | Thickness of soil layer associated with TSOIL3 | m | ft or in |

| dzgt4 | Thickness of soil layer associated with TSOIL4 | m | ft or in |

| dzgt5 | Thickness of soil layer associated with TSOIL5 | m | ft or in |

| dzgt6 | Thickness of soil layer associated with TSOIL6 | m | ft or in |

| poros | Soil porosity in volumetric units | m–3 m–3 | ft–3 ft–3 |

Table 5. List of vertically integrated diagnostics (tavg1_2d_int_Nx) variables for potential pavement application.

| Name | Description | Units (SI) | U.S. Equivalent Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| LWGNET | Surface net downward longwave flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWTNET | Upwelling longwave flux at top of the atmosphere (TOA) | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| PRECLS | Large scale rainfall | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 or in |

| SWNETSRF | Surface net downward shortwave flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWNETTOA | TOA net downward shortwave flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| HFLUX | Sensible heat flux from turbulence | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

Table 6. List of radiation diagnostics (tavg1_2d_rad_Nx) variables for potential pavement applications.

| Name | Description | Units (SI) | U.S. Equivalent Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALBEDO | Surface albedo | 1 | 1 |

| CLDHGH | Cloud area fraction for high clouds | 1 | 1 |

| CLDLOW | Cloud area fraction for low clouds | 1 | 1 |

| CLDMID | Cloud area fraction for middle clouds | 1 | 1 |

| CLDTOT | Total cloud area fraction | 1 | 1 |

| EMIS | Surface emissivity | 1 | 1 |

| LWGAB | Surface absorbed longwave radiation | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWGABCLR | Surface absorbed longwave radiation assuming clear sky | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWGABCLRCLN | Surface absorbed longwave radiation assuming clear sky and no aerosol | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWGEM | Longwave flux emitted from surface | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWGNT | Surface net downward longwave flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| Name | Description | Units (SI) | U.S. Equivalent Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| LWGNTCLR | Surface net downward longwave flux assuming clear sky | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWGNTCLRCLN | Surface net downward longwave flux assuming clear sky and no aerosol | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWTUP | Upwelling longwave flux at TOA | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWTUPCLR | Upwelling longwave flux at TOA assuming clear sky | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| LWTUPCLRCLN | Upwelling longwave flux at TOA assuming clear sky and no aerosol | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWGDN | Surface incoming shortwave flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWGDNCLR | Surface incoming shortwave flux assuming clear sky | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWGNT | Surface net downward shortwave flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWGNTCLN | Surface net downward shortwave flux assuming no aerosol | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWGNTCLR | Surface net downward shortwave flux assuming clear sky | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWGNTCLRCLN | Surface net downward shortwave flux assuming clear sky and no aerosol | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWTDN | TOA incoming shortwave flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWTNT | TOA net downward shortwave flux | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWTNTCLN | TOA net downward shortwave flux assuming no aerosol | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWTNTCLR | TOA net downward shortwave flux assuming clear sky | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| SWTNTCLRCLN | TOA net downward shortwave flux assuming clear sky and no aerosol | W m–2 | BTU ft–2 h–1 |

| TS | Surface skin temperature | K | K |

3.1.1.1 Summary of Unit Conversions

The MERRA-2 assimilated data are distributed in SI units, which may or may not require additional conversions to match those required by the EICM. Table 7 summarizes the unit conversions for the most common variables. The conversions listed in Table 7 were used throughout the analysis procedures in the subsequent tasks.

3.1.2 MERRA-2 Data Extraction and Evaluation

3.1.2.1 Data Extraction: Downloading MERRA-2 Data

MERRA-2 includes recent upgrades to the atmospheric assimilation, which enable the use of newer satellite observations that could not be assimilated in the original MERRA system. Additionally, MERRA-2 benefits from advances in the Goddard EOS, version 5 (GEOS-5) Atmospheric General Circulation Model (AGCM). MERRA-2 covers the period from 1980 to the present and continues to be updated with latency on the order of weeks. The AGCM is run on a cube-sphere grid with an approximate resolution of 50 km × 50 km, the atmospheric analysis operates on a Gaussian grid of the same resolution, and the output fields are interpolated to a

Table 7. Summary of units and conversion factors between MERRA-2 data and the EICM requirements.

| Variable Name | MERRA-2 Units | U.S. Customary | EICM Requirement | Conversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Flux Density | W/m2 | BTU/h-ft2 | BTU/h-ft2 | 1 W/m2 = 0.317 BTU/h-ft2 |

| Temperature | K | °F | °F or °C | 1 K = –457.87 °F, 1 K = –272.15 °C |

| Rainfall/Precipitation | kg m–2 s–1 | lb ft–2 s–1 | in or mm | Density of water = 1,000 kg m–3 1 kg m–2 = 1 mm of water 1 kg m–2 s–1 = 1 mm s–1 1 h = 60 min = 3,600 s 1 kg m–2 s–1 * 3,600 s = mm/h |

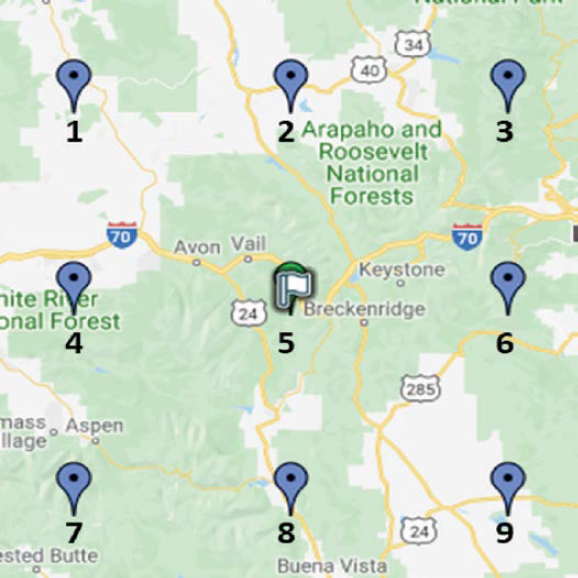

0.5° × 0.625° regular latitude–longitude grid prior to publication. For this research, the MERRA-2 variables listed in Tables 2 through 6 were extracted for a representative set of geographical locations covering the typical climatic regions, based on temperature and moisture, throughout the United States, as shown in Figure 1.

While the NASA Goddard Earth Sciences (GES) Data and Information Services Center (DISC) provides a web tool for sub-selecting and downloading the MERRA-2 database, it is a manual process and still requires the user to be able to know how to appropriately access and download needed data from the various data libraries and tables. The research team investigated multiple ways to work with GES DISC data resources using Python and open-source libraries, such as Request, Pydap, Xarray, and netCDF4-python. The Pydap library was chosen for this research project and is described as a convenient Python library that provides access to GES DISC OPeNDAP resources. It offers an interface for Python programs to read from OPeNDAP servers and also utilizes the netCDF4-Python module, which leverages the netCDF-C library to access the data. A MERRA-2 data download module using Pydap was developed, which requires authorized registration with GES DISC to download the data. Additionally, as described earlier, five different datasets were utilized to extract the climate variables for the 67 locations with different climate zones across the continental United States. Therefore, a total of 268 data tables were created to store all potential variables for each location. It should be mentioned that several limitations or issues were encountered that delayed the extraction process slightly. The main limitation was due to a “connection time exceeded” error that often occurred when attempting to download data over too many days because the server was receiving multiple requests from many users. The expected connection time to the server was approximately 2.5 h at a time. To overcome this problem, only the data corresponding to the grid covering the selected 67 locations were accessed and extracted. Additionally, the amount of data downloaded at one time was segmented to reduce processing and connection time to server.

3.1.2.2 Data Evaluation

Many of the datasets or data tables include similarly named variables. For example, net longwave and shortwave radiation data are included in the Flux, Radiation, and Land datasets, which may or may not be equivalent. Similarly named variables within each dataset were identified and compared to determine whether they are similar or different from one another. A brief description of one of the differences between the Flux and Land dataset collections is provided here (13):

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FLUX DATA INCLUDED IN THE FLX COLLECTION AND THE LND COLLECTION?

MERRA’s land parameterization is Randy Koster’s Catchment model, but other surfaces, such as inland water, ocean surface and glaciers are also accounted for as sub-grid tiles. In the LND collection of variables, all the data are derived from the land model, and are not weighted according to the land fraction at that grid point. This data is provided to better compute land budgets for soil water and land energy.

The data in FLX, RAD or any other collection of variables represent the gridbox average of all the different tiles weighted by their fractional cover. This is where you would use evaporation to compute the atmospheric energy balance. The important distinction here is that LND is land only, while all other collections are representative of the whole grid box.

The common variables identified between the MERRA-2 datasets were analyzed to determine whether they correlated with one another. The results from the analysis will help determine the recommended final list of variables for inclusion in the LTPP InfoPave Climate Tool database. The comparisons focused on the longwave, shortwave, and total net radiation at the Earth’s surface.

The dataset names were renamed to help make them more descriptive and easily identifiable. The renamed datasets are listed here:

- tavg1_2d_lnd_Nx becomes LAND

- – Represents assimilated climate variables over land only. The fraction of data over water is not included in the assimilation process.

- tavg1_2d_int_Nx becomes INT

- – Represents assimilated climate variables over land and water.

- tavg1_2d_rad_Nx becomes RAD

- – Represents assimilated radiative forcing climate variables over land and water.

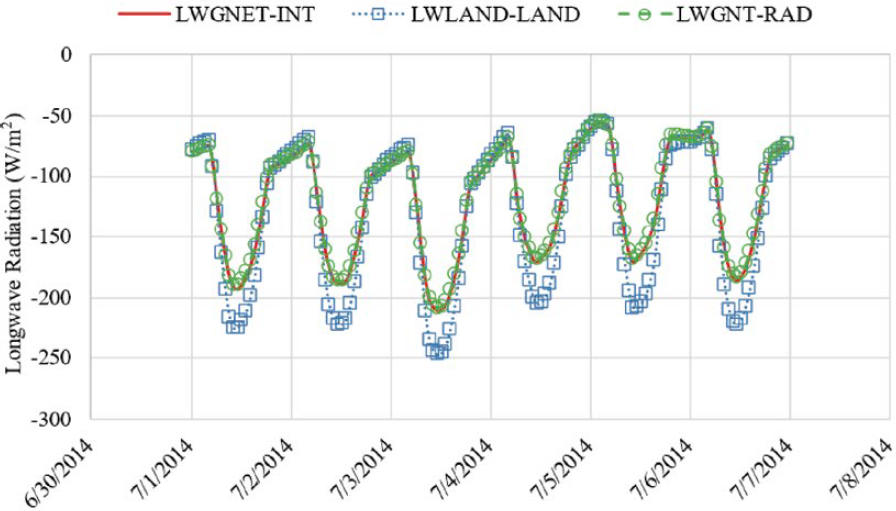

Longwave Radiation

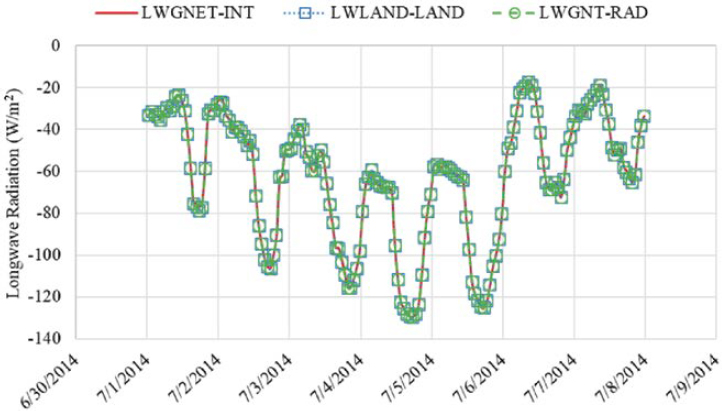

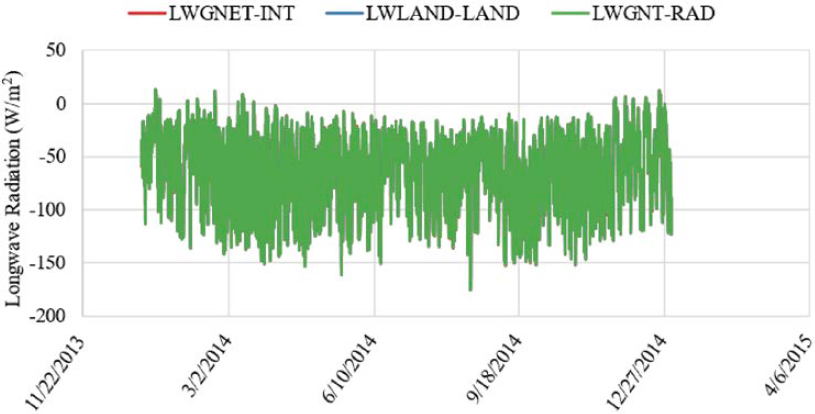

The net downward longwave radiation variables at the Earth’s surface for the different dataset collections are listed here and illustrated in Figure 2:

- LWLAND-LAND – Net longwave radiation over land area only within nodal area.

- LWGNET-INT – Surface net downward longwave flux over land and water within nodal area.

- LWGNT-RAD – Surface net downward longwave flux over land and water areas within nodal area.

Figure 2 shows that almost no distinct differences existed between the three MERRA-2 data tables for this variable for a 7-day period in July 2014. The location for this example is near Indianapolis, Indiana, where there are no large bodies of water, which explains why there are no

large differences in longwave radiation between the LAND, INT, and RAD MERRA-2 tables. When a particular node and/or grid box includes areas over water, a larger difference is expected. Figure 3 shows the same data for all of 2014, which shows a similar trend as observed for the 7-day period.

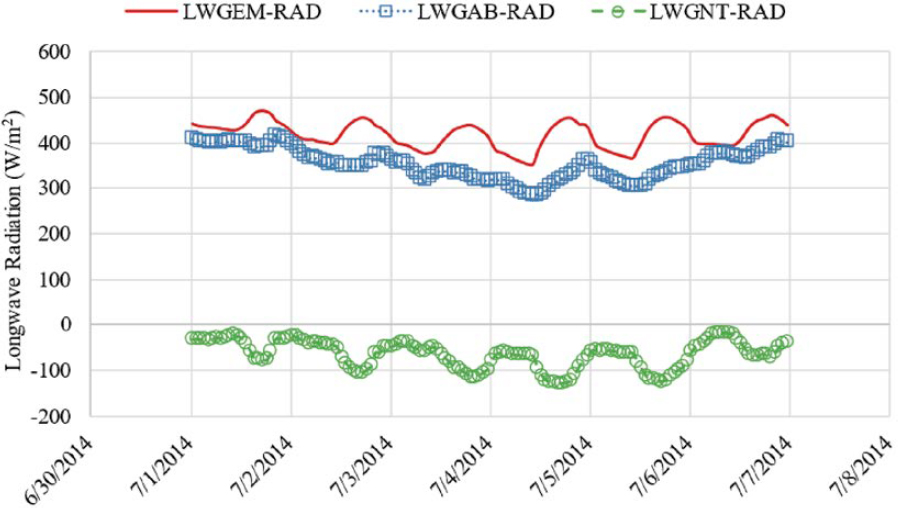

The net incoming (+) and outgoing (−) longwave radiation variables within the RAD MERRA-2 table, which are used to determine the total net longwave radiation for a specific grid point location, are listed here:

- LWGAB-RAD – Surface absorbed longwave radiation over land and water areas within nodal area.

- LWGEM-RAD – Longwave flux emitted from the surface over land and water areas within nodal area.

- LWGNT-RAD – Surface net downward longwave flux over land and water areas within nodal area.

Figure 4 shows an example of each variable for a 7-day period in July 2014. The net downward longwave flux (LWGNT-RAD) represents the difference between the incoming longwave radiation absorbed by the surface (LWGAB-RAD) and the outgoing longwave radiation emitted by the surface (LWGEM-RAD). Typically, the emitted longwave radiation is greater than the absorbed longwave radiation, which results in a net negative value, as observed in Figure 4.

Shortwave Radiation

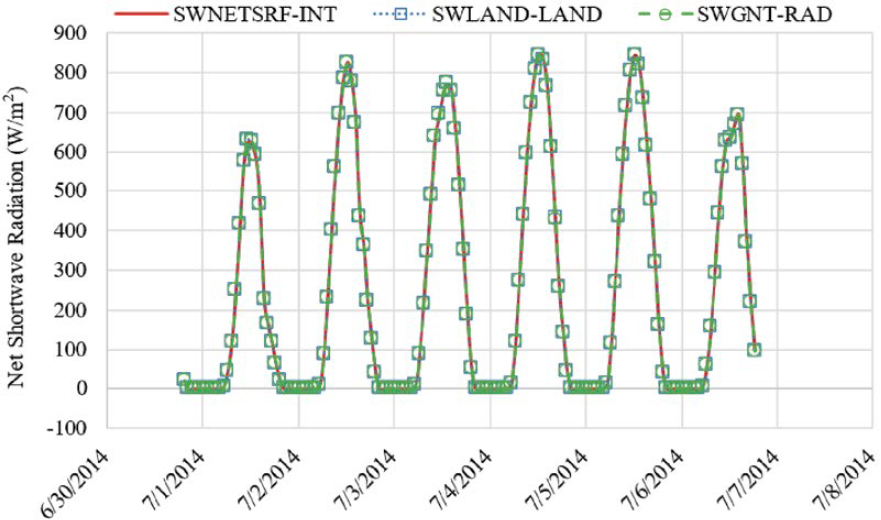

The net incoming shortwave radiation at the Earth’s surface for the three different MERRA-2 data tables are listed and defined here:

- SWLAND-LAND – Net shortwave radiation over land area only within total nodal area.

- SWNETSRF-INT – Surface net downward shortwave flux over land and water within nodal area.

- SWGNT-RAD – Surface net downward shortwave flux over land and water within nodal area.

Figure 5 illustrates the 7-day hourly net shortwave radiation values from the three MERRA-2 data tables. Minimal differences were observed between the three variables, indicating no significant difference in water fraction within the nodal area.

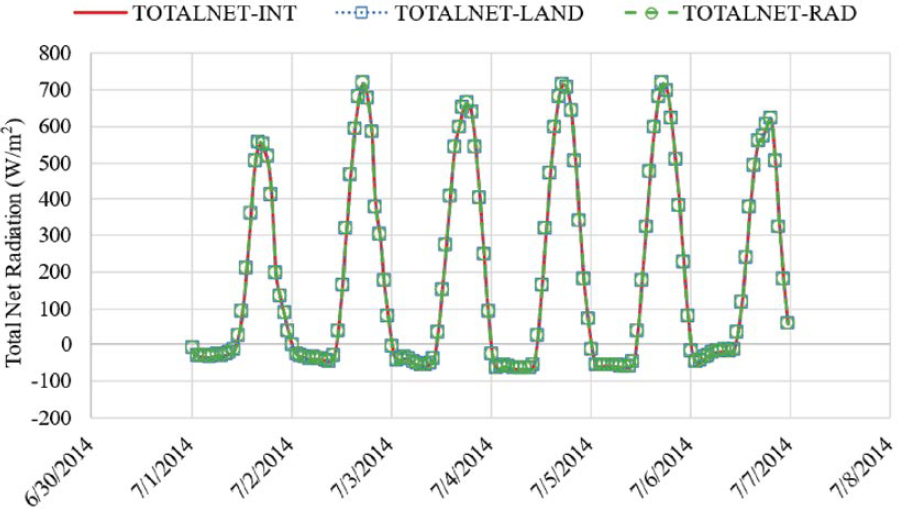

Total Net Radiation

The total net radiation, which was calculated using the net shortwave and net longwave data presented previously, at the Earth’s surface for the three different MERRA-2 data tables is listed and defined here:

- TOTALNET-LAND = SWLAND-LAND + LWLAND-LAND

- TOTALNET-INT = SWNETSRF-INT + LWGNET-INT

- TOTALNET-RAD = SWGNT-RAD + LWGNT-RAD

The total net solar radiation for each of the three MERRA-2 data tables is illustrated in Figure 6. For this example, the results are nearly identical between the different data tables, which is expected since the individual components (i.e., shortwave and longwave radiation indices) are also nearly identical. It is expected that larger differences will be observed between the LAND, INT, and RAD datasets when the nodal area includes a larger fraction of water.

Locations with Larger Water Fractions

In areas where the MERRA-2 nodal area has a larger fraction of water, differences will be observed between the three data tables. Typically, the longwave radiation is affected the most because of the differences between how water and land emit the longwave radiation back into the atmosphere. The MERRA-2 LAND data showed lower net longwave radiation compared to the other two datasets, as shown in Figure 7, for a grid point location near Los Angeles, California (CA). Overall, the total net radiation (i.e., shortwave and longwave) did show a slight difference between the different datasets because of the differences in longwave radiation.

3.1.3 Final List of Variables

Based on the comparisons presented in this section, the final list of MERRA-2 variables for different MERRA-2 data collections is summarized in Table 8.

3.1.4 Proposed Process to Extract and Include Input Variables

The following list is a proposed step-by-step process for updating the LTPP InfoPave Climate Tool with additional MERRA-2 variables:

- Update LTPP InfoPave MERRA database design to accommodate additional selected climate data attributes.

- Deploy Amazon Relational Database Service (RDS) database for Oracle to hold the extracted data for the selected climatic data attributes.

- Deploy an application server to host the utility applications for data download and processing.

Table 8. MERRA-2 data tables and variables to analyze in depth.

| MERRA-2 Table Name | MERRA-2 Variables | MERRA-2 Variable Description |

| Land surface diagnostics (tavg1_2d_lnd_Nx) | LWLAND | Net longwave over land only |

| SWLAND | Net shortwave over land only | |

| LHLAND | Latent heat flux land | |

| SHLAND | Sensible heat flux land | |

| PRECTOTLAND | Total precipitation land; bias corrected | |

| Vertically integrated diagnostics (tavg1_2d_int_Nx) | LWGNET | Surface net downward longwave flux |

| SWNETSRF | Surface net downward shortwave flux | |

| PRECLS | Large scale rainfall | |

| Radiation diagnostics (tavg1_2d_rad_Nx) | LWGAB | Surface absorbed longwave radiation |

| LWGEM | Longwave flux emitted from surface | |

| LWGNT | Surface net downward longwave flux | |

| LWTUP | Upwelling longwave flux at TOA | |

| SWGDN | Surface incoming shortwave flux | |

| SWGNT | Surface net downward shortwave flux |

- Download MERRA-2 Product raw files for additional selected climate data attributes.

- Extract data from the raw files and populate the temporary database.

- Update the LTPP InfoPave MERRA database schema based on the updated design.

- Move the extracted data to the LTPP InfoPave MERRA database.

- Process the hourly data and populate the summary and roll up tables.

- Develop metadata for the additional climate data attributes.

- Update the LTPP InfoPave Climate Tool to include newly added climate data attributes (optional).

- Update the LTPP InfoPave MERRA Extraction Service to include newly added climate data attributes (optional).

- Back up and decommission the Amazon RDS and application servers.

3.2 Developing Enhancements of Climatic Inputs and Related Models for Future Incorporation in Pavement ME Design

3.2.1 Enhance the EICM Earth–Atmosphere Energy Balance Model

3.2.1.1 Use of MERRA-2 Hourly Shortwave and Longwave Radiation Data

In the previous section, the variables listed in Table 8 from different MERRA-2 tables were extracted for 60+ locations spanning the continental United States, representing the four LTPP defined climatic regions or zones. The locations and climatic zones from which the MERRA-2 data were extracted are shown in Figure 1.

For each of the locations shown in Figure 1, the following steps were performed to analyze and compare the energy balance variables using different MERRA-2 tables and the empirically calculated longwave, shortwave, and total net radiation at the ground surface:

- Calculate the net longwave, shortwave, and total radiation using the empirical formulas currently implemented in the EICM.

- Extract the longwave and shortwave data variables from each MERRA-2 table listed in Table 8.

- Calculate the annual and monthly descriptive statistics for each location and climatic region.

- Compare the calculated net longwave, shortwave, and total radiation based on the empirical formulas (Step 1) to the equivalent MERRA-2 variables.

- Determine whether significant differences exist between the MERRA-2 data variables and the empirically calculated results from the EICM.

The results for each component of the total energy balance equation are summarized in the following section.

Analysis Methods

For each of the climatic variables (i.e., longwave, shortwave, and total net radiation), the following procedure was employed to determine whether statistically significant differences exist between the EICM-calculated energy balance values and the MERRA-2 variables.

Statistical Analysis Definitions and Procedure

- Perform a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine whether a significant difference exists in mean values between climate datasets and climate zones using the selected locations.

- – Dependent variable: Mean annual longwave radiation

- – Independent variables:

- Climate dataset with four factor levels (i.e., EICM, LAND, INT, and RAD)

- Climate zone with four factor levels (i.e., wet freeze, wet non-freeze, dry freeze, and dry non-freeze)

-

ANOVA model form:

- – Mean annual value (longwave, shortwave, total net radiation) = climate dataset + climate zone + climate dataset * climate zone

- – Main effects: climate dataset + climate zone

- – Contrasts or interactive terms: climate dataset * climate zone

- Alternative model form:

- – Mean = climate dataset * climate zone

- – This model will test both the main effects and interactive effects.

- If any of the main effects or interactive effects were found to be significant, the Tukey Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test would be performed to determine which levels within each main effect and interactive effects were found to be significant.

Define Hypotheses

- Is there a difference between the climate datasets for longwave, shortwave, and total net radiation?

- – Null Hypothesis: There is no difference between the EICM-calculated values and any of the MERRA-2 datasets.

- – Alternative Hypothesis: There is a difference in one or more of the climate datasets used in the analysis.

- Is there a difference between the climate zones within each climate dataset?

- – Null hypothesis: There is no difference between the climate zones within each climate dataset.

- – Alternate Hypothesis: There is a difference in any of the climate zones.

- Are there any interactive effects between the independent variable groups or within each variable group?

- – Null hypothesis: There is no difference between or within each independent variable group.

- – Alternate Hypothesis: There is a difference between or within any of the independent variable groups.

The analysis results are presented and discussed for each climate variable in the following sections:

- Net Longwave Radiation Analysis Results

- Net Shortwave Radiation Analysis Results

- Net Total Radiation Analysis and Results

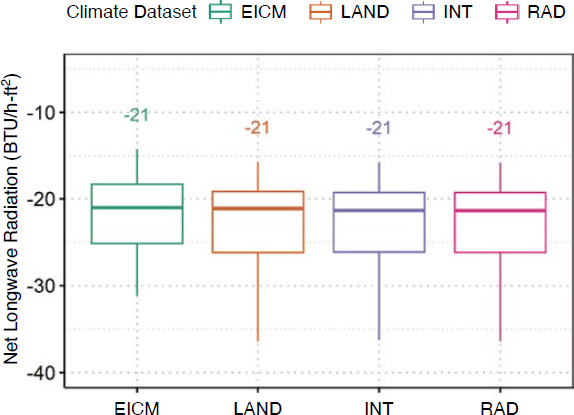

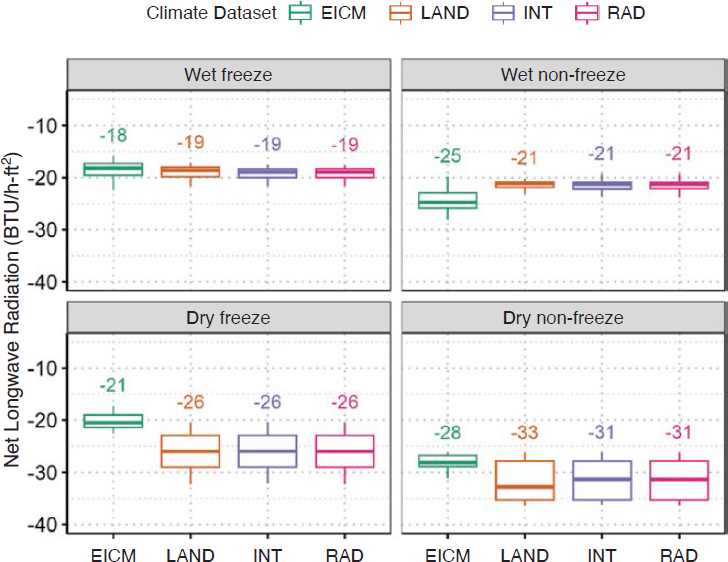

Net Longwave Radiation Analysis Results

Results and Discussion. The boxplot distributions of average annual net longwave radiation were generated to compare the range of values included for each climate dataset, as shown in Figure 8. The same data are then separated by each climate region, as shown in Figure 9. Within each figure, the value shown represents the median value, the box represents the interquartile range (IQR), and the whisker lines represent values no higher than 1.5 times above and below the IQR.

The following observations were made:

- The mean annual net longwave radiation is a negative value because the outgoing longwave radiation emitted from the surface is greater than the longwave radiation absorbed from the atmosphere. It is assumed that the incoming longwave radiation is positive while the outgoing or emitted longwave radiation is negative.

- The EICM-calculated net longwave radiation showed similar magnitudes to the MERRA-2 data when all climatic zones are included, as shown in Figure 8. When the data are separated by climatic zone (Figure 9), it can be seen that similar values were observed for the wet-freeze locations while larger differences were observed for the other three climatic zones. The larger

- differences observed for the climatic zones outside of wet-freeze are not surprising because the empirical equations were originally developed using data from locations around the mid-western United States, which is one of the limitations within the EICM addressed in this study.

- The largest overall difference between the EICM-calculated longwave radiation and the MERRA-2 data was observed in the dry freeze and dry non-freeze climatic zones. In both cases, the EICM empirical calculations showed higher net longwave radiation compared to the MERRA-2 data.

The ANOVA statistical analysis results are summarized in Table 9. The highlighted cells in Tables 9 through 14 denote the statistical significance of the independent variables at an alpha level of 0.05. The results show that both main effects (i.e., climate dataset and climate zone) and interactive effects were significantly different than the null hypothesis and conclude that one or

Table 9. ANOVA results for longwave radiation testing main and interactive effects.

| Model Term | Degrees of Freedom (DF) | Sum Sq. | Mean Sq. | Statistic | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| climate.dataset | 3.000 | 77.100 | 25.700 | 3.499 | 0.016 |

| climate.zone | 3.000 | 3,778.237 | 1,259.412 | 171.459 | 0.000 |

| climate.dataset:climate.zone | 9.000 | 428.215 | 47.579 | 6.478 | 0.000 |

| residuals | 248.000 | 1,821.627 | 7.345 |

more mean differences were found to be different. To identify which groups and levels were significant, the Tukey HSD test was performed to compare multiple comparisons simultaneously.

The results from the Tukey HSD analysis are summarized in Table 10. Adjusted p-values with four asterisks have a significance level equal to 0, p-values with one asterisk have a significance level greater than 0.01 but less than 0.05, and p-values deemed not significant have a significance level greater than 0.05 (these definitions also apply to the adjusted p-values in Tables 12 and 14). The Group 1 variables were compared to the corresponding Group 2 variables to determine whether the means were significantly different from one another. The complete analysis compares all combinations between the climate dataset levels and climate zone levels. Some of these combinations are not necessarily relevant to the overall conclusions and were excluded from Table 10. One such example is the interaction between the EICM dataset within the wet-freeze climate zone compared to the MERRA-2 RAD dataset in the dry-freeze climate zone. A significant difference could be within that combination. Instead, the comparisons were reported when the climate zone from Group 1 was equal to Group 2. Based on the results shown, the following items were highlighted:

- The EICM empirically calculated longwave radiation showed a statistically significant difference when compared to the MERRA-2 INT and RAD tables and not the LAND table.

- None of the MERRA-2 tables showed a statistically significant difference when compared to one another.

- All climatic regions were significantly different from one another.

- The interactive effects found to be significant were the EICM data within the dry-freeze climatic zone compared to the MERRA-2 LAND, INT, and RAD data. These results coincide with the boxplot summaries shown in Figure 9 for the dry freeze climatic zone.

In summary:

- Statistically significant differences were observed between the EICM empirically calculated longwave radiation and the MERRA-2 datasets and between different climatic zones.

- The most important finding from this analysis is that the empirical equations used to calculate longwave radiation showed significant differences in climatic regions, which were not accounted for when the models were developed. Specifically, the differences between the EICM and MERRA-2 data are a function of the following:

- – Constants included in the empirical method were derived from data primarily collected in the Midwestern United States and the wet freeze climatic region. The constants are likely not representative of the other climatic regions.

- – Differences between cloud cover and how it affects the total longwave radiation. The EICM requires a single value for overall cloud cover, while the MERRA-2 data are assimilated based on cloud cover at different heights throughout. The cloud cover height can affect the amount of longwave radiation reflected back to the surface.

- Overall, the authors concluded that the MERRA-2 data are a more representative dataset, which does not rely on regression constants or factors derived based on data within a specific climatic region.

Table 10. Summary of important main and interactive effects for longwave radiation.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Estimate | Conf. Low | Conf. High | Adj. P-Value | Signif? (ns = not significant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EICM | Land | –1.187 | –2.407 | 0.034 | 0.060 | ns |

| EICM | Int | –1.274 | –2.494 | –0.054 | 0.037 | * |

| EICM | Rad | –1.275 | –2.495 | –0.055 | 0.037 | * |

| Land | Int | –0.088 | –1.308 | 1.133 | 0.998 | ns |

| Land | Rad | –0.089 | –1.309 | 1.132 | 0.998 | ns |

| Int | Rad | –0.001 | –1.221 | 1.219 | 1.000 | ns |

| Wet freeze | Wet non-freeze | –3.125 | –4.208 | –2.043 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet freeze | Dry freeze | –5.587 | –6.760 | –4.413 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet freeze | Dry non-freeze | –11.758 | –13.145 | –10.371 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet non-freeze | Dry freeze | –2.461 | –3.658 | –1.264 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet non-freeze | Dry non-freeze | –8.632 | –10.039 | –7.225 | 0.000 | **** |

| Dry freeze | Dry non-freeze | –6.171 | –7.649 | –4.693 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM:Wet freeze | Land:Wet freeze | –0.383 | –3.212 | 2.446 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Wet freeze | Int:Wet freeze | –0.602 | –3.430 | 2.227 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Wet freeze | Rad:Wet freeze | –0.590 | –3.419 | 2.238 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Wet freeze | Int:Wet freeze | –0.218 | –3.047 | 2.610 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Wet freeze | Rad:Wet freeze | –0.207 | –3.036 | 2.622 | 1.000 | ns |

| Int:Wet freeze | Rad:Wet freeze | 0.011 | –2.818 | 2.840 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Wet non-freeze | Land:Wet non-freeze | 2.269 | –0.698 | 5.236 | 0.371 | ns |

| EICM:Wet non-freeze | Int:Wet non-freeze | 2.144 | –0.823 | 5.111 | 0.474 | ns |

| EICM:Wet non-freeze | Rad:Wet non-freeze | 2.139 | –0.828 | 5.106 | 0.478 | ns |

| Land:Wet non-freeze | Int:Wet non-freeze | –0.125 | –3.092 | 2.842 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Wet non-freeze | Rad:Wet non-freeze | –0.130 | –3.096 | 2.837 | 1.000 | ns |

| Int:Wet non-freeze | Rad:Wet non-freeze | –0.005 | –2.972 | 2.962 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Dry freeze | Land:Dry freeze | –5.549 | –8.975 | –2.123 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM:Dry freeze | Int:Dry freeze | –5.582 | –9.008 | –2.157 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM:Dry freeze | Rad:Dry freeze | –5.586 | –9.012 | –2.160 | 0.000 | **** |

| Land:Dry freeze | Int:Dry freeze | –0.034 | –3.459 | 3.392 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Dry freeze | Rad:Dry freeze | –0.037 | –3.463 | 3.389 | 1.000 | ns |

| Int:Dry freeze | Rad:Dry freeze | –0.004 | –3.429 | 3.422 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Dry non-freeze | Land:Dry non-freeze | –3.559 | –7.981 | 0.864 | 0.285 | ns |

| EICM:Dry non-freeze | Int:Dry non-freeze | –3.334 | –7.756 | 1.089 | 0.397 | ns |

| EICM:Dry non-freeze | Rad:Dry non-freeze | –3.351 | –7.774 | 1.072 | 0.388 | ns |

| Land:Dry non-freeze | Int:Dry non-freeze | 0.225 | –4.198 | 4.648 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Dry non-freeze | Rad:Dry non-freeze | 0.207 | –4.215 | 4.630 | 1.000 | ns |

| Int:Dry non-freeze | Rad:Dry non-freeze | –0.017 | –4.440 | 4.405 | 1.000 | ns |

Net Shortwave Radiation Analysis Results

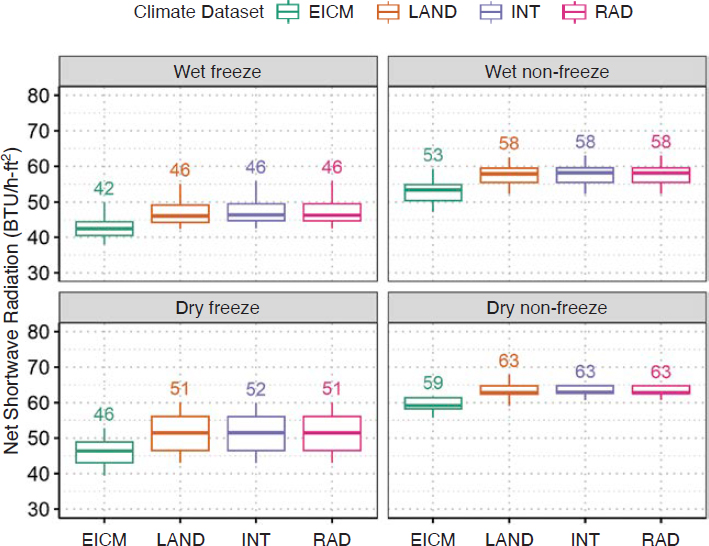

Results and Discussion. The boxplot summaries for the annual net shortwave radiation for each climate dataset are shown in Figure 10. Figure 11 subdivides the data for each climatic region.

The following observations were made:

- In general, the EICM empirically calculated net shortwave radiation was lower than the MERRA-2 datasets, as shown in Figure 10. The MERRA-2 LAND, INT, and RAD shortwave radiation data were nearly identical.

- When comparing the boxplots for each climate zone, as shown in Figure 11, the EICM-calculated shortwave radiation was less than the MERRA-2 datasets for all climatic zones.

Table 11. ANOVA results for shortwave radiation testing main and interactive effects.

| Model Term | DF | Sum Sq. | Mean Sq. | Statistic | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| climate.dataset | 3.000 | 1,161.117 | 387.039 | 16.567 | 0.000 |

| climate.zone | 3.000 | 8,287.454 | 2,762.485 | 118.248 | 0.000 |

| climate.dataset:climate.zone | 9.000 | 7.437 | 0.826 | 0.035 | 1.000 |

| residuals | 248.000 | 5,793.716 | 23.362 |

- The wet-freeze and dry non-freeze climatic zones showed the smallest difference between the EICM-calculated and MERRA-2 net shortwave radiation, while the largest differences were observed in the dry freeze and wet non-freeze climate zones.

- For the locations selected, the dry-freeze climate zone showed the largest range of values, as represented by the IQR.

- The differences between the EICM-calculated and MERRA-2 datasets observed for net longwave radiation are most likely due to how cloud cover or percent sunshine is accounted for and the empirical equation constants derived using locations within the wet-freeze climatic region.

The ANOVA statistical analysis results for net shortwave radiation are summarized in Table 11. The results show that only the main effects (i.e., climate dataset and climate zone) were significantly different, while the interaction terms were not. This result indicates that the interaction term can be removed from the ANOVA model. Since the main effects had significantly different means, it was concluded that one or more mean differences were different. The Tukey HSD test was performed to identify which levels within the climate dataset and climate zone are different from one another. Since the interactive effects were not found to be significant, the ANOVA model was updated to only include the main effects.

The results from the Tukey HSD analysis are summarized in Table 12. The Group 1 variables were compared to the corresponding Group 2 variables to identify which combination of levels

Table 12. Summary of important main and interactive effects for shortwave radiation.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Estimate | Conf. Low | Conf. High | Adj. P-Value | Signif? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EICM | Land | 4.700 | 2.561 | 6.839 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM | Int | 4.917 | 2.778 | 7.055 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM | Rad | 4.901 | 2.762 | 7.040 | 0.000 | **** |

| Land | Int | 0.217 | –1.922 | 2.355 | 0.994 | ns |

| Land | Rad | 0.201 | –1.937 | 2.340 | 0.995 | ns |

| Int | Rad | –0.015 | –2.154 | 2.123 | 1.000 | ns |

| Wet freeze | Wet non-freeze | 9.182 | 7.284 | 11.080 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet freeze | Dry freeze | 3.912 | 1.855 | 5.969 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet freeze | Dry non-freeze | 16.605 | 14.175 | 19.036 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet non-freeze | Dry freeze | –5.270 | –7.368 | –3.172 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet non-freeze | Dry non-freeze | 7.423 | 4.958 | 9.889 | 0.000 | **** |

| Dry freeze | Dry non-freeze | 12.693 | 10.103 | 15.283 | 0.000 | **** |

is significantly different from one another. Based on the results shown, the following observations were highlighted:

- The EICM empirically calculated shortwave radiation showed a statistically significant difference when compared to the any of the MERRA-2 datasets.

- Similar to longwave radiation, none of the MERRA-2 datasets showed a statistically significant difference when compared to another MERRA-2 dataset.

- All climatic regions were significantly different from one another.

In summary:

- For shortwave radiation, the ANOVA results showed that statistically significant differences were found for the main effects (i.e., climate dataset and climate zone). None of the interactive effects resulted in a significant difference and were removed from the ANOVA model.

- The EICM calculated net shortwave radiation was found to be significantly different than all of the MERRA-2 datasets.

- Overall, the authors concluded that the MERRA-2 datasets were more representative for different climate zones compared to the empirically calculated net shortwave radiation.

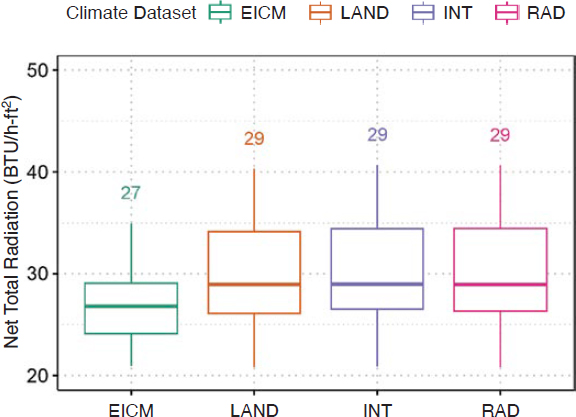

Net Total Radiation Analysis Results

Results and Discussion. The total net radiation is calculated by summing the net shortwave and net longwave radiation. The boxplot summary for total net radiation for each climate dataset is shown in Figure 12, while the same data separated by climate zone are shown in Figure 13.

The following observations were made:

- The total net radiation for the EICM dataset showed a lower median value compared to any of the MERRA-2 datasets. Additionally, the range of values was also much less compared to the MERRA-2 datasets.

- The MERRA-2 datasets showed nearly identical boxplot summaries.

- After separating the climate datasets for each climate zone, as shown in Figure 13, several differences were observed. The EICM total net radiation within the wet freeze and wet non-freeze climate zones was less than the MERRA-2 total net radiation datasets. The EICM-calculated dry freeze and dry non-freeze zones showed median values much closer in magnitude and range compared to the MERRA-2 datasets.

- The differences observed between the total net radiation were similar to those observed and discussed for net shortwave radiation.

The results from the ANOVA for net total radiation are summarized in Table 13. The results show that both the main effects (i.e., climate dataset and climate zone) and interactive effects had significantly different means. The Tukey HSD test was performed to identify which levels within the climate dataset and climate zone were different from one another.

The results from the Tukey HSD analysis are summarized in Table 14. Based on the results, the following observations were documented:

- The EICM empirically calculated total net radiation showed a statistically significant difference compared to all three of the MERRA-2 datasets, while the MERRA-2 datasets were not significantly different from one another.

- All comparisons between levels of climate zones were significantly different except for the comparison between the wet non-freeze and dry non-freeze climate zones.

- Two of the interactive effects resulted in significant differences. The EICM data within the wet freeze and wet non-freeze climatic zones were significantly different than their MERRA-2 counterparts within the same climate zone. None of the dry freeze and dry non-freeze comparisons resulted in significantly different means.

Table 13. ANOVA results for total net radiation testing of main and interactive effects.

| Model Term | DF | Sum Sq. | Mean Sq. | Statistic | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| climate.dataset | 3.000 | 640.015 | 213.338 | 17.620 | 0.000 |

| climate.zone | 3.000 | 2,766.998 | 922.333 | 76.177 | 0.000 |

| climate.dataset:climate.zone | 9.000 | 384.063 | 42.674 | 3.525 | 0.000 |

| residuals | 248.000 | 3,002.706 | 12.108 |

Table 14. Summary of important main and interactive effects for total net radiation.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Estimate | Conf. Low | Conf. High | Adj. P-Value | Signif? (ns = not significant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EICM | Land | 3.513 | 1.947 | 5.080 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM | Int | 3.642 | 2.076 | 5.209 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM | Rad | 3.626 | 2.059 | 5.193 | 0.000 | **** |

| Land | Int | 0.129 | – 1.438 | 1.696 | 0.997 | ns |

| Land | Rad | 0.113 | – 1.454 | 1.679 | 0.998 | ns |

| Int | Rad | –0.016 | – 1.583 | 1.550 | 1.000 | ns |

| Wet freeze | Wet non-freeze | 6.057 | 4.666 | 7.447 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet freeze | Dry freeze | –1.675 | – 3.181 | –0.168 | 0.023 | * |

| Wet freeze | Dry non-freeze | 4.848 | 3.067 | 6.628 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet non-freeze | Dry freeze | –7.731 | – 9.268 | –6.194 | 0.000 | **** |

| Wet non-freeze | Dry non-freeze | –1.209 | – 3.015 | 0.597 | 0.310 | ns |

| Dry freeze | Dry non-freeze | 6.522 | 4.625 | 8.420 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM:Wet freeze | Land:Wet freeze | 3.930 | 0.298 | 7.562 | 0.020 | * |

| EICM:Wet freeze | Int:Wet freeze | 4.058 | 0.426 | 7.690 | 0.013 | * |

| EICM:Wet freeze | Rad:Wet freeze | 4.025 | 0.393 | 7.657 | 0.015 | * |

| Land:Wet freeze | Int:Wet freeze | 0.128 | – 3.504 | 3.760 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Wet freeze | Rad:Wet freeze | 0.095 | – 3.537 | 3.727 | 1.000 | ns |

| Int:Wet freeze | Rad:Wet freeze | –0.033 | – 3.665 | 3.599 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Wet non-freeze | Land:Wet non-freeze | 7.052 | 3.243 | 10.861 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM:Wet non-freeze | Int:Wet non-freeze | 7.082 | 3.273 | 10.891 | 0.000 | **** |

| EICM:Wet non-freeze | Rad:Wet non-freeze | 7.068 | 3.259 | 10.877 | 0.000 | **** |

| Land:Wet non-freeze | Int:Wet non-freeze | 0.030 | – 3.779 | 3.839 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Wet non-freeze | Rad:Wet non-freeze | 0.016 | –3.793 | 3.825 | 1.000 | ns |

| Int:Wet non-freeze | Rad:Wet non-freeze | –0.014 | –3.823 | 3.795 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Dry freeze | Land:Dry freeze | –0.112 | –4.510 | 4.287 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Dry freeze | Int:Dry freeze | –0.141 | –4.540 | 4.257 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Dry freeze | Rad:Dry freeze | –0.121 | –4.520 | 4.277 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Dry freeze | Int:Dry freeze | –0.030 | –4.428 | 4.369 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Dry freeze | Rad:Dry freeze | –0.009 | –4.408 | 4.389 | 1.000 | ns |

| Int:Dry freeze | Rad:Dry freeze | 0.020 | –4.378 | 4.419 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Dry non-freeze | Land:Dry non-freeze | 0.673 | –5.006 | 6.351 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Dry non-freeze | Int:Dry non-freeze | 1.288 | –4.391 | 6.966 | 1.000 | ns |

| EICM:Dry non-freeze | Rad:Dry non-freeze | 1.247 | –4.431 | 6.926 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Dry non-freeze | Int:Dry non-freeze | 0.615 | –5.063 | 6.293 | 1.000 | ns |

| Land:Dry non-freeze | Rad:Dry non-freeze | 0.574 | –5.104 | 6.253 | 1.000 | ns |

| Int:Dry non-freeze | Rad:Dry non-freeze | –0.041 | –5.719 | 5.638 | 1.000 | ns |

In summary:

- For total net radiation, the ANOVA results showed that statistically significant differences were found for the main effects (i.e., climate dataset, climate zone) and interactive effects.

- The EICM-calculated total net radiation was significantly different than all of the MERRA-2 datasets.

Summary and Conclusions

Based on the results presented, the following conclusions were reported:

- The EICM empirically calculated net longwave, shortwave, and total radiation values were significantly different than the MERRA-2 datasets.

- The MERRA-2 LAND, INT, and RAD tables were not significantly different than one another for net longwave, shortwave, and total radiation. Any of the datasets can be selected to populate hourly shortwave and longwave radiation for use in the EICM. The authors recommend using the MERRA-2 LAND table because it only represents the climatic conditions over land.

- Many of the differences between the EICM-calculated net longwave and shortwave radiation are due to the models and regression constants being developed using data from a specific region, which is not representative of other climatic zones or locations.

- The authors recommend enhancing the EICM by allowing the use of hourly longwave and shortwave radiation instead of the empirical equations currently used.

3.2.1.2 Investigate the Predefined Limits Set on the Convective Heat Transfer Equations

The heat transfer due to convection at the Earth’s surface, Qc, is calculated using the following equation:

Qc = H(Tair − T1)

The convection coefficient, H, is computed using an empirical equation developed by Vehrencamp (3, 14) as shown here:

where Vm is the average of the air temperature and pavement surface temperature in K, Uwind is the wind velocity in mph converted to m/s (1 mph = 0.447 m/s), T1 is the surface temperature in °C, and Tair is the air temperature in °C. The value of 122.93 converts the units from g − cal/min − cm2 − °C to BTU/h − ft2 − °F. The wind velocity input in the EICM is in mph and converted to m/s, hence the 0.447 multiplier in the equation. The value of 1.33 is not well defined and is of an unknown origin. The maximum allowed convection coefficient is a hard-coded value set to 3.0 BTU/h − ft2 − °F. The value was selected to ensure stability within the analysis module when the analysis increments are large. The EICM within the PMED uses an analysis increment of 0.1 h, which is short enough not to cause any stability issues. Therefore, the maximum convection coefficient can be adjusted or removed entirely. The convection coefficient limit value within the EICM input file was adjusted to quantify the impact on the predicted output results. Several values were used; however, none of them had any impact on the predicted outputs.

3.2.2 EICM Feature Enhancements

3.2.2.1 Spatial Interpolation Methods

Currently Implemented Methods

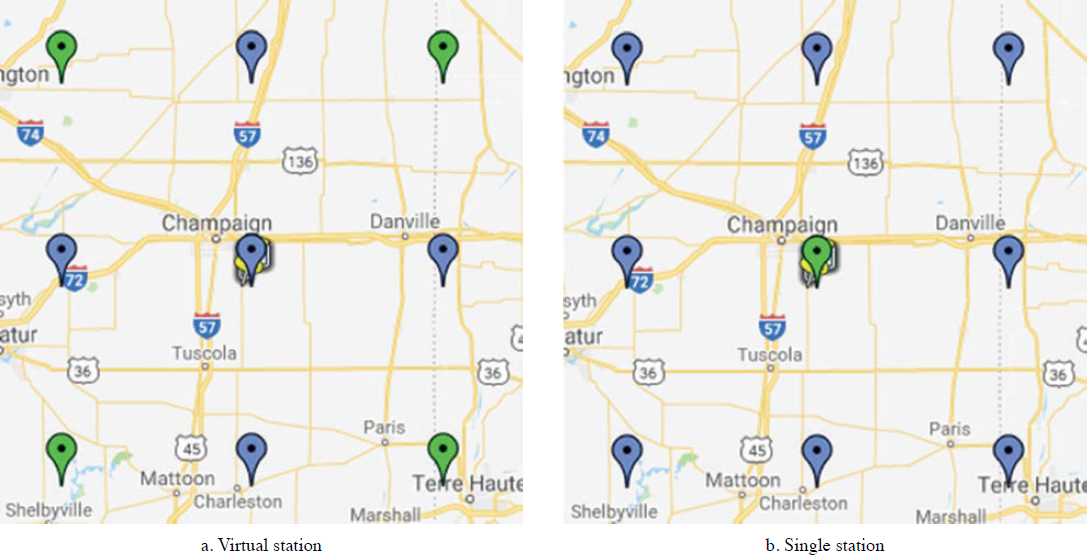

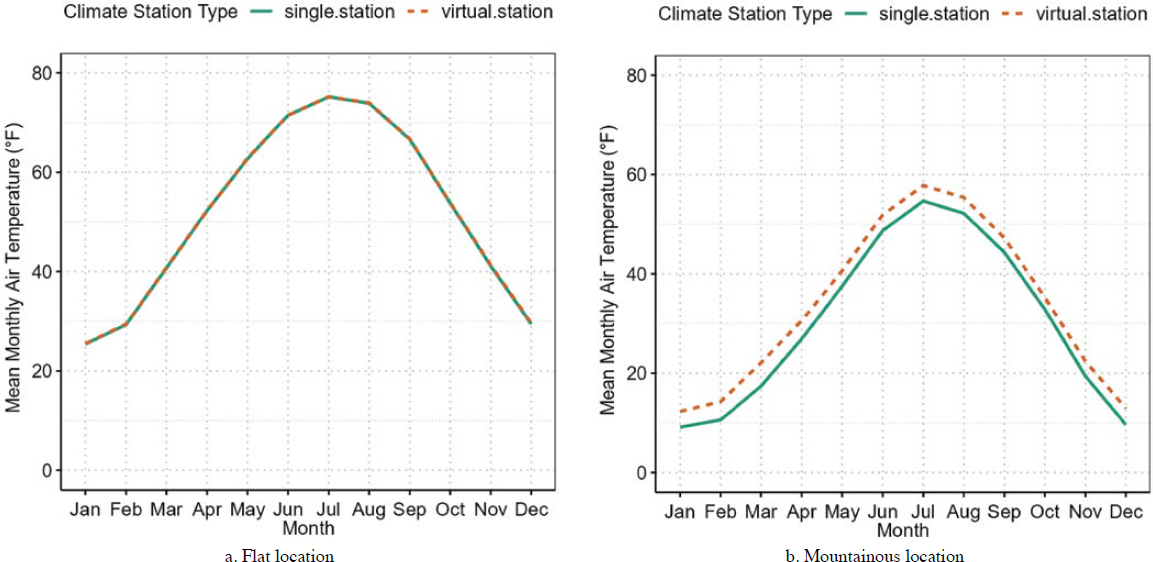

The PMED software allows users to create a “virtual” climate station when their specific project location is too far from a MERRA-2 grid point. The Mechanistic–Empirical Pavement Design Guide: A Manual of Practice (MEPDG MOP) (15) also suggests using a virtual climate station when significant elevation differences are observed between the MERRA-2 grid point location and a selected location. The default search algorithm within the PMED software automatically filters the displayed MERRA-2 grid points by elevation closest to the actual selected location and then by distance. Once multiple MERRA-2 grid point locations are selected, the PMED software creates a virtual climate station using the inverse squared distance weighting method as mentioned in the literature review. For illustration purposes, the PMED software was used to create a virtual station to represent a specific MERRA-2 grid point for two locations. The first location represents a relatively flat area, while the second represents an area with larger elevation differences between MERRA-2 grid points. Figure 14 illustrates the selected grid point locations for the first example, while Figure 15 represents the selected locations for the second example. The green virtual station point locations in Figures 14a and 15a are used to interpolate the data for the green single station point locations in Figures 14b and 15b, respectively. The blue virtual and single station point locations in both figures overall represent the available MERRA-2 gridpoint locations.

The single station and virtual station analysis compares the different hourly climate data that feed into the EICM analysis module. The comparisons consist of air temperature for this analysis. The virtual or interpolated station data are expected to be a reasonable representation of the single station data. Each hourly climate data file has continuous hourly data from 1985 to 2018. The monthly average temperature values are compared for the flat and mountainous locations. Figure 16 illustrates the differences between the two geographical locations for the virtual climate station and the single station. The results show that the monthly average temperatures for the virtual station are almost identical to the single station data for the flat region. Alternatively,

Figure 15. MERRA-2 grid point locations selected to compare a virtual station to an individual MERRA-2 grid point for a highly variable elevation area.

a clear difference is observed between the virtual climate station and single climate station for the mountainous location. For this case, the virtual station consistently showed higher annual temperatures compared to the single station. These differences are not surprising because the hourly MERRA-2 data are grid based and represent a specific elevation, latitude, and longitude. The squared distance weighting algorithm identifies and uses the closest station as the starting point for the interpolation process.

The inverse distance weighted interpolation method may not be appropriate for all geographical locations. Other more sophisticated spatial interpolation methods have been developed that may provide a better estimate for locations between MERRA-2 grid points. Many of these methods were discussed in the literature review. Several of these methods were analyzed to compare differences between interpolated values of temperature, wind speed, precipitation, percent sunshine, and relative humidity to determine whether they provide a better representation for most geographical locations.

Additional Interpolation Methods for Potential Use

The option to create a virtual or “interpolated” climate station or location is significantly important in PMED in the absence of an exact physical weather station near the pavement construction location. The use of additional interpolation methods that can capture the variability between geographical locations, especially elevations or altitude differences, is important to mimic what the pavement structure will experience throughout its life. Using accurate location-specific hourly climate estimates within the EICM will help provide more accurate pavement performance predictions that match the field performance. Several research studies have tested and recommended the use of alternative interpolation methods to overcome some of the identified limitations. A geostatistical interpolation method called kriging was evaluated to determine whether it can provide improved interpolated hourly climate data compared to the inverse distance weighted (IDW) method, especially in areas where large elevation differences over a short distance are present.

Kriging. Spatial interpolation is a fundamental tool in the realm of geostatistics and spatial analysis and essential for estimating values at unsampled locations based on known/provided data points. Among the plethora of interpolation methods available, kriging stands out as a sophisticated and powerful technique with wide-ranging applications across various disciplines, including environmental science, geology, agriculture, and urban planning.

Kriging, initially developed by the French mathematician Georges Matheron in the 1950s, is rooted in the principles of geostatistics and spatial statistics. Unlike simpler interpolation methods, such as IDW or polynomial interpolation, which often lack robustness and fail to account for spatial dependence, kriging offers a more rigorous and statistically sound approach to spatial estimation. The general formula for both interpolators is formed as a weighted sum of the data, which can be calculated using the following equation:

where Z(si) is the measured or known value at the i-th location, λi is a weight factor for the measured value at the i-th location, s0 represents the location where values are interpolated or predicted, and N is the number of measured values.

The weight factor, λi, is based not only on the distance between the measured points and the prediction location but also on the overall spatial arrangement of the measured points. To use the spatial arrangement in the weights, the spatial autocorrelation must be quantified. At its core, kriging leverages the concept of spatial autocorrelation, recognizing that nearby locations tend to

have more similar values than distant ones. By analyzing the spatial structure of the data through variogram modeling, kriging provides not only point estimates but also measures of uncertainty associated with those estimates, making it particularly valuable for decision-making and risk assessment in spatially distributed phenomena. The versatility of kriging lies in its ability to adapt to various spatial patterns and data characteristics. Whether dealing with irregularly spaced point data, continuous surfaces, or categorical variables, kriging offers different variants, such as ordinary, simple, and universal, each tailored to specific scenarios and assumptions.

Variogram. A variogram is a fundamental tool used in geostatistics to characterize the spatial dependence or autocorrelation of a spatial dataset. It quantifies the degree of similarity between pairs of data points as a function of their separation distance. Variograms are particularly important in kriging because they provide information about the spatial structure of the variable being interpolated, which is essential for determining kriging weights and making accurate predictions at unsampled locations. The variogram is calculated by computing the variance of the differences between pairs of data points as a function of their separation distance. The variogram plot typically consists of the distance (lag) on the x-axis and the semi-variance (or variance of differences) on the y-axis. Variograms often exhibit distinct patterns or behaviors, which can be characterized by fitting variogram models. These models help summarize the spatial dependence structure of the data and provide parameters that can be used in kriging interpolation. A subset of the variogram models is discussed briefly here:

- Spherical

- – The spherical model assumes that spatial correlation between data points reaches a maximum value (i.e., sill) at a certain distance (i.e., range), beyond which the correlation levels off and remains constant.

- – The model is characterized by a rapid increase in semi-variance with increasing distance until the range is reached, after which it levels off to the sill value.

- Exponential

- – The exponential model describes spatial correlation as decreasing exponentially with increasing distance between data points.

- – Unlike the spherical model, there is no abrupt leveling-off of the semi-variance; instead, it gradually decreases away from the sill as distance increases.

- Gaussian

- – Similar to the exponential model, the Gaussian model describes spatial correlation as decreasing with increasing distance, but it does so more gradually.

- – The decrease in semi-variance follows a Gaussian or bell-shaped curve, with slower decay compared to the exponential model.

- Hole-Effect

- – The Hole-effect model accounts for situations in which spatial correlation initially decreases at short distances (the “hole” effect), followed by a gradual increase to a plateau.

- – It is often observed in datasets in which localized areas of low correlation surrounded by areas of high correlation are present.

Evaluation of Geographical Distinctions

As discussed earlier, two distinct geographical regions were selected for spatial interpolation: an area with relatively constant elevations (i.e., a flat region) and an area with highly variable elevations changes (i.e., a mountainous region). Each region was represented by a 3-by-3 grid of MERRA-2 data points, where the center grid point is considered the “ground truth” or target value for spatial interpolation. Within each geographical region, the grid points were grouped by similar elevations (lower and higher elevation groups) and another that included all points. This grouping categorization aimed to evaluate the impact of elevation on the interpolation results and assess the performance of kriging across different elevation levels for distinct geographical characteristics.

For the mountainous region, the MERRA-2 ID 143543 (Location 5 in Figure 17) was selected along with the surrounding eight MERRA-2 grid points. The eight surrounding points were divided into two groups based on similar elevation levels. Figure 17 illustrates the selected grid point locations for the mountainous region, and Table 15 summarizes the details of each grid point along with their categorization. IDs 1, 2, 4, 8, and 9 in Table 15 were categorized as the low elevation group, while IDs 3, 6, and 7 were categorized as the high elevation group.

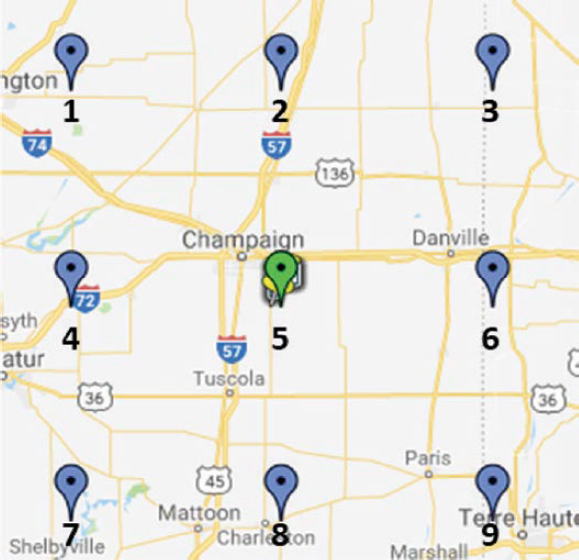

Similar to the mountainous region, MERRA-2 ID-144148 (Location 5 in Figure 18), along with the eight surrounding MERRA-2 grid points, was selected to represent the locations with minimal elevation differences for spatial interpolation. Figure 18 illustrates the selected grid

Table 15. Mountainous location summary data.

| ID | MERRA -2 ID | Elevation (ft) | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 144118 | 8,875 | 40.0 | –106.875 | Group 1 |

| 2 | 144119 | 8,095 | 40.0 | –106.250 | Group 1 |

| 3 | 144120 | 11,525 | 40.0 | –105.625 | Group 2 |

| 4 | 143542 | 8,150 | 39.5 | –106.875 | Group 1 |

| 5 | 143543 | 11,270 | 39.5 | –106.250 | Baseline |

| 6 | 143544 | 12,500 | 39.5 | –105.625 | Group 2 |

| 7 | 142966 | 12,811 | 39.0 | –106.875 | Group 2 |

| 8 | 142967 | 9,462 | 39.0 | –106.250 | Group 1 |

| 9 | 142968 | 8,905 | 39.0 | –105.625 | Group 1 |

point locations for the flat region, and Table 16 summarizes the details of each grid point along with the elevation group categories. IDs 1, 2, 3, and 4 in Table 16 were grouped to represent the low elevation group, while IDs 6, 7, 8, and 9 represent the high elevation group.

Spatial Interpolation Results. The data period of each grid point is from 1985 to 2021 and collected temperature, wind speed, percent sunshine, precipitation, and relative humidity for every hour.

As discussed earlier, the grid points at each region were placed into three categories: low elevation points (Group 1), high elevation points (Group 2), and all points (8 points). Spatial interpolation using 2D kriging was then conducted on each category. Moreover, selecting the

Table 16. Flat location summary data.

| ID | MERRA -2 ID | Elevation (ft) | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 144723 | 842 | 40.5 | –88.750 | Group 1 |

| 2 | 144724 | 770 | 40.5 | –88.125 | Group 1 |

| 3 | 144725 | 725 | 40.5 | –87.500 | Group 1 |

| 4 | 144147 | 682 | 40.0 | –88.750 | Group 1 |

| 5 | 144148 | 682 | 40.0 | –88.125 | Baseline |

| 6 | 144149 | 524 | 40.0 | –87.500 | Group 2 |

| 7 | 143571 | 688 | 39.5 | –88.750 | Group 2 |

| 8 | 143572 | 675 | 39.5 | –88.125 | Group 2 |

| 9 | 143573 | 596 | 39.5 | –87.500 | Group 2 |

most appropriate variogram model is crucial for accurate interpolation results. Since variogram modeling involves fitting a theoretical model to empirical variogram data, testing multiple variogram models helps identify the model that best describes the observed spatial dependence patterns. Root mean squared error (RMSE) was used to evaluate model performance and select the most appropriate variogram model for interpolation.

The spatial interpolation results using 2D kriging for a mountainous region are summarized in Table 17. Based on the analysis results, similar RMSE values were exhibited across variogram models within each category. However, considering the consistent pattern across all three categories, where the Gaussian model generally yields the lowest RMSE values for most variables, both Group 1 (low elevation) and Group 2 (high elevation) categories showed similar patterns of performance, with the Gaussian variogram model consistently outperforming other models. However, since the 8-points category exhibited relatively lower RMSE values overall, representing the spatial interpolation using the surrounding eight grid points can capture spatial dependence patterns and produce accurate predictions across variables without considering elevation differences.

The spatial interpolation results using 2D kriging for the relatively flat regions are summarized in Table 18. Based on the analysis results, the 8-points category represents the overall spatial variability across the flat region, without considering elevation differences. The lower RMSE values in this category suggest that the spatial dependence patterns for the variables tend to be more consistent or predictable across different locations in the flat region.

Despite similar RMSE values across variogram models within each category, the Hole-effect variogram model showed the lowest RMSE across the grouping categories and climatic variables overall. Moreover, the higher RMSE for percent sunshine may be influenced by its unique characteristics as a percentage variable or because of localized variability with respect to cloud cover. Standard variogram models might not be able to capture the nonlinearity or high variability associated with the percent sunshine values.

Table 17. Spatial interpolation results using 2D kriging for a mountainous region.

| Interpolation Group | Variogram Model | Temperature (°C) | Wind Speed (mph) | Percent Sunshine (%) | Precipitation (in) | Relative Humidity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 Points | Exponential | 5.165 | 2.205 | 11.433 | 0.009 | 8.684 |

| Gaussian | 4.857 | 1.958 | 11.963 | 0.009 | 8.079 | |

| Hole-Effect | 5.681 | 2.134 | 11.841 | 0.010 | 9.432 | |

| Spherical | 5.609 | 2.138 | 11.793 | 0.010 | 9.299 | |

| Group 1 (Low Elevation) | Exponential | 5.664 | 2.559 | 12.736 | 0.011 | 9.183 |

| Gaussian | 4.872 | 2.464 | 12.369 | 0.010 | 8.215 | |

| Hole-Effect | 6.126 | 2.403 | 13.209 | 0.011 | 9.883 | |

| Spherical | 6.099 | 2.415 | 13.158 | 0.011 | 9.788 | |

| Group 2 (High Elevation) | Exponential | 4.830 | 1.760 | 12.597 | 0.010 | 9.356 |

| Gaussian | 4.356 | 1.665 | 12.595 | 0.010 | 8.946 | |

| Hole-Effect | 4.531 | 1.688 | 12.736 | 0.010 | 8.576 | |

| Spherical | 5.145 | 1.815 | 12.777 | 0.010 | 9.792 |

Table 18. Spatial interpolation results using 2D kriging for a flat region.

| Interpolation Group | Variogram Model | Temperature (°C) | Wind Speed (mph) | Percent Sunshine (%) | Precipitation (in) | Relative Humidity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 Points | Exponential | 1.089 | 0.963 | 10.962 | 0.017 | 2.810 |

| Gaussian | 1.495 | 1.116 | 13.606 | 0.019 | 3.663 | |

| Hole-Effect | 1.032 | 0.941 | 10.576 | 0.017 | 2.684 | |

| Spherical | 1.048 | 0.946 | 10.674 | 0.017 | 2.723 | |

| Group 1 (Low Elevation) | Exponential | 1.449 | 1.132 | 12.449 | 0.019 | 3.231 |

| Gaussian | 1.556 | 1.166 | 13.053 | 0.019 | 3.499 | |

| Hole-Effect | 1.422 | 1.129 | 12.323 | 0.019 | 3.159 | |

| Spherical | 1.422 | 1.129 | 12.329 | 0.019 | 3.168 | |

| Group 2 (High Elevation) | Exponential | 1.760 | 1.242 | 14.755 | 0.020 | 3.858 |

| Gaussian | 1.771 | 1.249 | 14.857 | 0.021 | 3.886 | |

| Hole-Effect | 1.791 | 1.258 | 14.920 | 0.021 | 3.929 | |

| Spherical | 1.786 | 1.255 | 14.908 | 0.021 | 3.922 |

2D kriging primarily focuses on interpolating values within a 2D plane or surface, such as a map or geographic area. While 2D kriging can capture some aspects of elevation differences within this plane, it does not directly model or interpolate variations in elevation in the vertical dimension. To capture vertical elevation differences directly, 3D kriging was also employed for spatial interpolation to capture spatial variability across both horizontal and vertical dimensions. However, since 3D kriging involves estimating values at unsampled locations within a 3D volume, it requires much more processing time compared to 2D kriging. Therefore, 1 year of data (1985) was utilized for 3D spatial interpolation using the Gaussian and Hole-effect variogram models for the mountainous and flat regions, respectively. This approach was applied separately to each region to generate the interpolated datasets. Table 19 summarizes the 2D and 3D spatial interpolation results for both regions. It should be noted that the results presented in Table 19 for 2D interpolation are based on data from the same period, specifically the year of 1985.

In the mountainous region, 3D interpolation yielded higher RMSE values compared to 2D interpolation across all variables in all categories. Conversely, in the flat region, those two interpolation results showed similar performances; however, 3D interpolation exhibited better performance in Group 1, providing lower RMSE values compared to 2D interpolation for most variables.

The results presented between 2D and 3D kriging were surprising because the initial assumption was that 3D kriging would result in lower RMSE values compared to the 2D analysis since it directly accounts for altitude when calculating the distance between the target location and the other grid points in the analysis. One of the suspected reasons higher RMSE values for 3D kriging were observed was the limited number of locations (i.e., 8 points) selected for this analysis and the highly variable elevation values corresponding to each grid point location.

As an additional check, the baseline grid point location (i.e., Location 5 in Figure 17) was included in the interpolation scheme as an additional point for the kriging interpolation. The location was added to the interpolation scheme because the aim was to study whether the interpolation method can estimate the MERRA-2 values better than when it is not included in the

Table 19. Spatial interpolation results using 2D and 3D kriging for a flat and mountainous regions.

| Geography Type | Interpolation Type | Interpolation Group | Temperature (ºC) | Wind Speed (mph) | Percent Sunshine (%) | Precipitation (in) | Relative Humidity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat | 3D | 8 Points | 1.193 | 1.026 | 10.824 | 0.015 | 2.423 |

| Group 1 – (Low Elevation) | 1.506 | 1.170 | 12.527 | 0.018 | 2.817 | ||

| Group 2 – (High Elevation) | 2.027 | 1.274 | 15.199 | 0.017 | 3.143 | ||

| 2D | 8 Points | 1.102 | 0.947 | 10.863 | 0.015 | 2.477 | |

| Group 1 – (Low Elevation) | 1.844 | 1.180 | 13.010 | 0.018 | 3.226 | ||

| Group 2 – (High Elevation) | 2.168 | 1.259 | 15.213 | 0.018 | 3.538 | ||

| Mountainous | 3D | 8 Points | 5.388 | 2.306 | 54.682 | 0.042 | 14.526 |

| Group 1 – (Low Elevation) | 5.679 | 2.579 | 24.331 | 0.012 | 8.801 | ||

| Group 2 – (High Elevation) | 5.716 | 1.987 | 13.002 | 0.009 | 9.444 | ||

| 2D | 8 Points | 4.661 | 2.035 | 12.294 | 0.009 | 7.376 | |

| Group 1 – (Low Elevation) | 4.728 | 2.580 | 12.434 | 0.010 | 7.498 | ||

| Group 2 – (High Elevation) | 4.507 | 1.657 | 12.375 | 0.009 | 8.240 |

interpolation dataset. The hypothesized result is lower RMSE value(s) when the baseline grid point is included in the analysis compared to when it is excluded from the analysis.

The following steps were followed to perform additional analysis:

- Add Location 5 to the interpolation dataset to perform kriging with all nine hourly data points.

- Interpolate the hourly climate data at a location close to the MERRA-2 grid point location.

- Adjust the “OrdinaryKriging” function inputs as follows:

- – Adjust the “weight” option to True. This option sets a greater weight for grid points closer to the interpolation location. In this case, Location 5 will be weighted more heavily since it is the closest MERRA-2 grid point to the specified location.

- Additional Use Cases

- – One benefit of the spatiotemporal interpolation methods is that they can interpolate values at multiple points. For example, if multiple coordinates along a roadway are specified, point value estimates can be determined for each point to represent “roadway specific” climate data. The MERRA-2 gridded system could be used to create a network of roadway-specific assimilated climate data.

The analysis results are summarized in Table 20, which showed significantly reduced RMSE values compared to the analysis that used only 8 points. When using the weighted by distance setting, the RMSE reduced further and is more aligned with the RMSE values obtained for the flat regions.

Summary of Results and Recommendations

- The currently implemented IDW interpolation method is adequate for most locations where large elevation changes over short distances are not present.

- Kriging can be more accurate if enough point locations are available and distances are not too large. Additionally, including the weighted setting within the kriging interpolation scheme reduced the overall RMSE.

- Correcting for elevation is still recommended.

- – The 3.5° temperature difference for 1,000 ft of elevation change is appropriate for temperature corrections. It is the standard lapse rate, which is used for aviation purposes. The standard lapse rate is 6.5 °C per km or 3.56 °F per 1,000 ft. The lapse rate is applicable between sea level and 11 km above the Earth’s surface.

- Future considerations

- – Identify points along interstate, state, and county roadways and interpolate hourly climate data based on the roadway network.

- – Integrate the kriging method as an option within the AASHTOWare Pavement ME Design software.

- Open-source Python, R, C#, or other packages may exist that can be integrated to perform the interpolation.

3.2.2.2 Adjusting Constant Deep Ground Temperature

The EICM procedure considers the MAAT as the lower boundary temperature. The current algorithm can be adjusted to set this temperature just above freezing (32 °F/0 °C) in all cases to allow the EICM to run for the areas where the MAAT is usually less than freezing. As a part of the annual updates, the PMED software and EICM, specifically, were updated to account for locations where the MAAT is below freezing. The implemented procedure sets the initial pavement temperature to 55 °F or 12.8 °C, which corresponds to the original value used when the EICM was developed.

Another potential solution for an initial nodal temperature is to use the average temperature corresponding to the unbound or granular base construction month. This solution assumes that the monthly average air temperature is greater than freezing. In most cases, the pavement construction seasons do not start until after the ground has thawed.

3.2.2.3 Investigate Methods to Improve Pavement Temperature Predictions During Precipitation Events

The EICM does not currently directly account for the change in pavement temperature with respect to precipitation. The pavement temperature is expected to closely reflect the air temperature during precipitation events, as the amount of rain or snow will either cool or warm the

Table 20. Spatial interpolation RMSE results using 2D kriging for a mountainous region using nine MERRA-2 grid point locations.

| Comparison Name | Distance Weighted? | Temperature (ºC) | Wind Speed (mph) | Percent Sunshine (%) | Precipitation (in) | Relative Humidity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original with 8 Points | No | 2.3659 | 0.94691 | 4.3865 | 0.0032533 | 3.4870 |

| Weighted by Distance | Yes | 1.5135 | 0.79046 | 4.3423 | 0.0031488 | 2.9273 |

pavement surface depending on the current climatic conditions. Different methods were investigated to identify potential improvements to the prediction of pavement temperature during precipitation events to closely reflect the measured pavement temperatures.

The following list summarizes the process used to complete this investigation:

- Identify variables within the MERRA-2 LAND database related to precipitation that affect the overall energy balance results. The following variables were identified:

- – Latent Heat Flux

- Defined as LHLAND in MERRA-2.

- Represents the transfer of latent heat between the land surface and the atmosphere due to evaporation and transpiration. It is associated with water vapor. Latent heat plays an important role in the overall water cycle and affects soil moisture and regional climates. Positive values indicate moisture release from the surface to the atmosphere, while negative values indicate moisture update by the surface.

- – Sensible Heat Flux

- Defined as SHLAND in MERRA-2.

- Represents the transfer of sensible heat (i.e., thermal energy) between the land surface and the atmosphere due to temperature differences. It quantifies the heat exchange resulting from the temperature gradient between the land surface and the air just above it. Sensible heat affects local weather patterns, air temperature, and boundary layer dynamics. Positive values indicate heat transfer from the surface to the atmosphere (e.g., warm ground heating the air), while negative values indicate heat transfer from the atmosphere to the surface (e.g., cooling of the ground).

- – Ground Heat Flux

- Defined as GHLAND in MERRA-2.

- Represents the heat transfer between the Earth’s surface (i.e., land) and the atmosphere due to conduction. It quantifies the energy exchange at the land surface. Ground heat flux is crucial for understanding land–atmosphere interactions, which influence local climate, soil temperature, and other non–pavement-related factors, such as vegetation growth. Positive values indicate heat transfer from the ground to the atmosphere (e.g., during daytime), while negative values indicate heat transfer from the atmosphere to the ground (e.g., during nighttime).

- – Total Precipitation

- Defined as PRECTOTLAND in MERRA-2.

- Represents the observation-corrected precipitation rate for specific time increment, 1 h, in this analysis. The raw values are converted from kg m−2 s−1 to mm/h (multiplying by 3,600 s) and then converted to in/h (multiplying by 25.4).

- – Latent Heat Flux

- Compare different energy balance variables to precipitation and identify whether any significant correlations exist.

- Compare different combinations of energy balance variables to calculate the total energy balance (Qrad).

Compare Different Energy Balance Variables

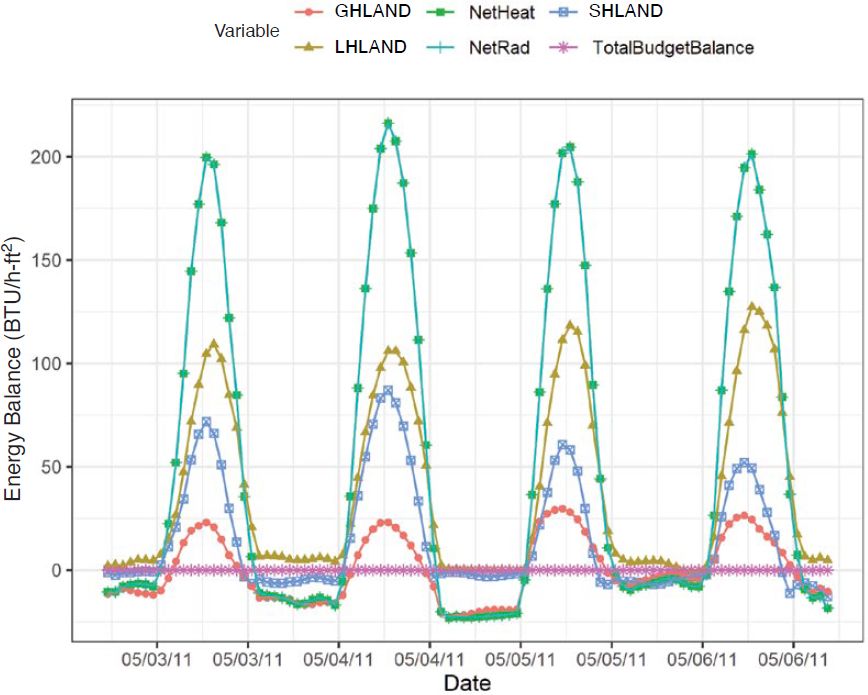

In addition to the variables defined above, additional variables were calculated to combine the radiation data and the heat flux data. The following variables were calculated:

- NetRad: Total net radiation equal to the sum of net shortwave and longwave radiation. These represent the radiative forcing variables.

- NetHeat: Total heat flux equal to the sum of the latent heat flux, sensible heat flux, and ground heat flux.

- TotalBudgetBalance: Total energy budget balance between NetRad and NetHeat. The sum of these two variables should be close to 0.

Figure 19 shows an example of the time series data for the energy variables defined above for a 4-day period in May 2011. The following observations were made:

- NetRad and NetHeat are nearly identical.

- TotalBudgetBalance is about equal to 0 for the selected time period.

- LHLAND, GHLAND, and SHLAND follow similar trends in which the values are much higher during daytime hours compared to nighttime hours.

- Based on these results, the sum of longwave and shortwave radiation is approximately equal to the sum of latent heat flux, sensible heat flux, and ground heat flux.

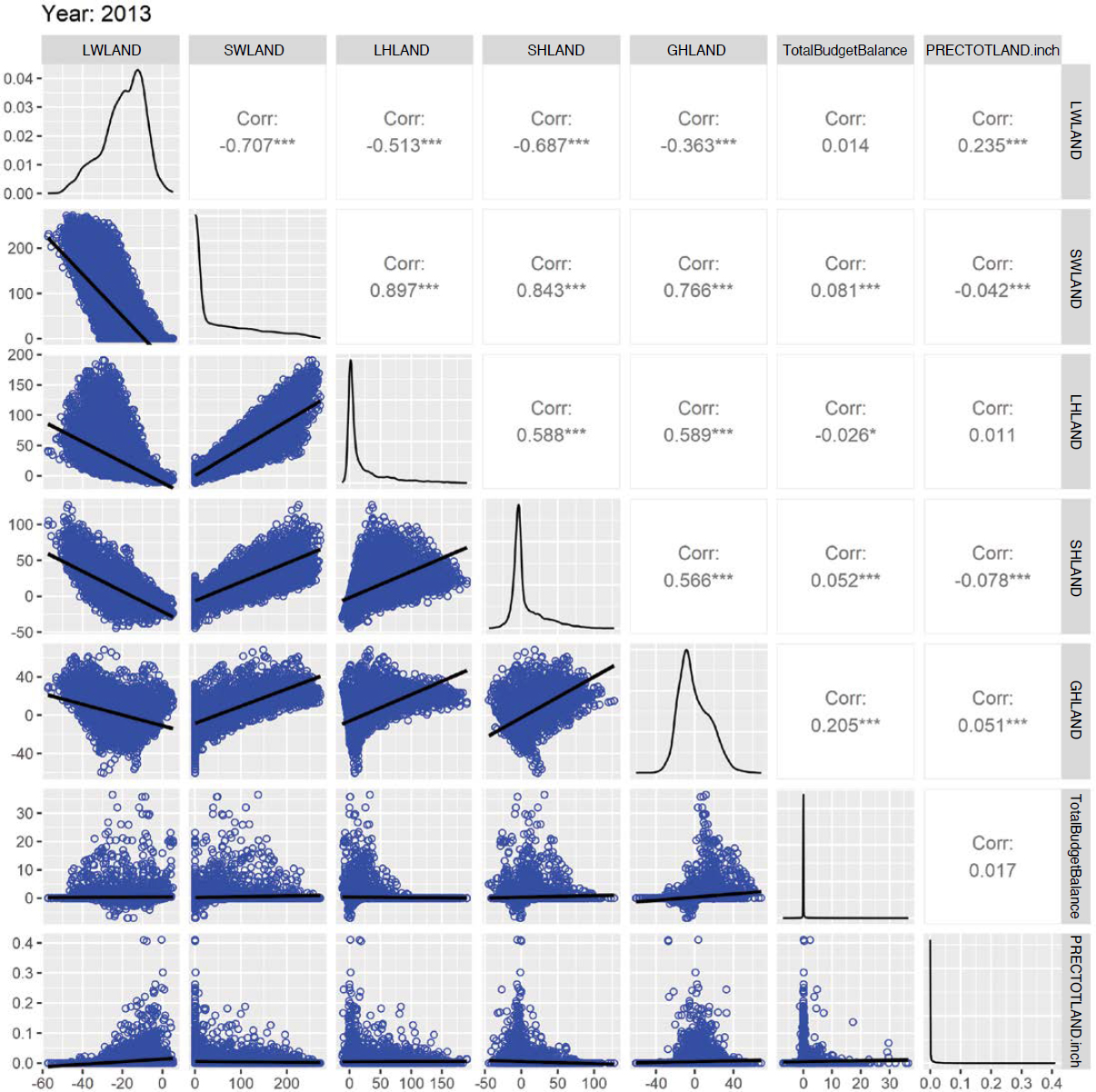

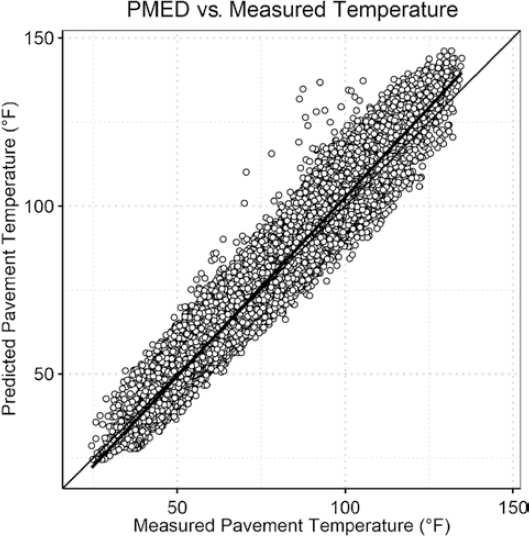

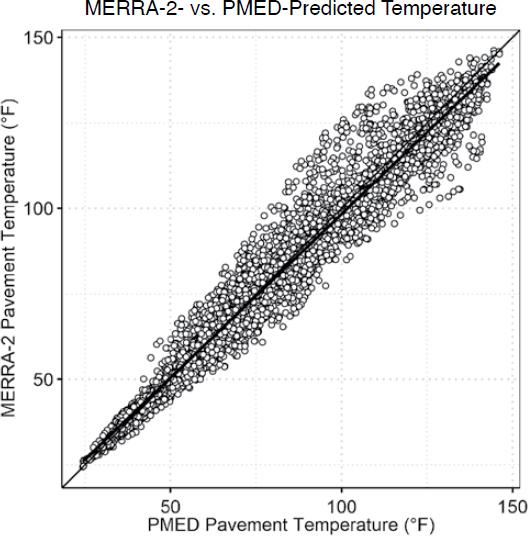

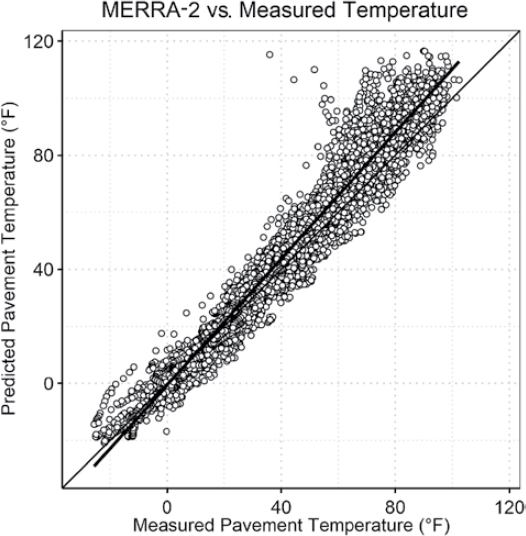

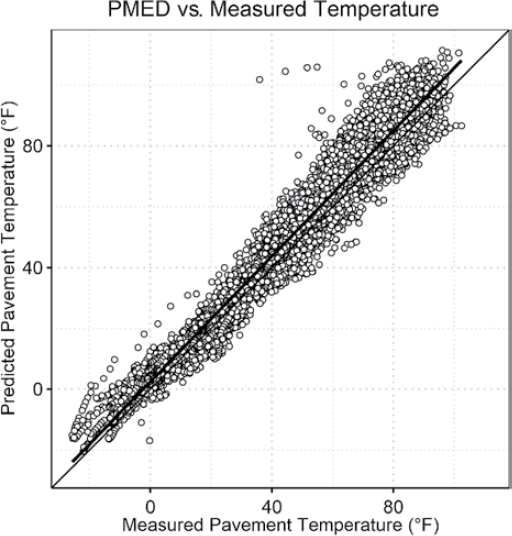

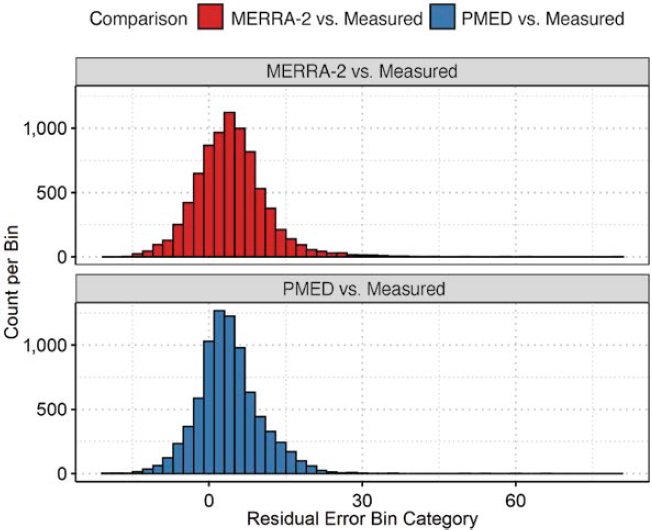

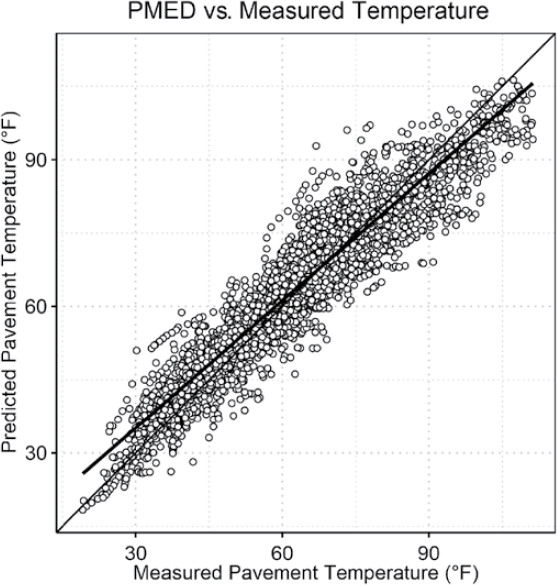

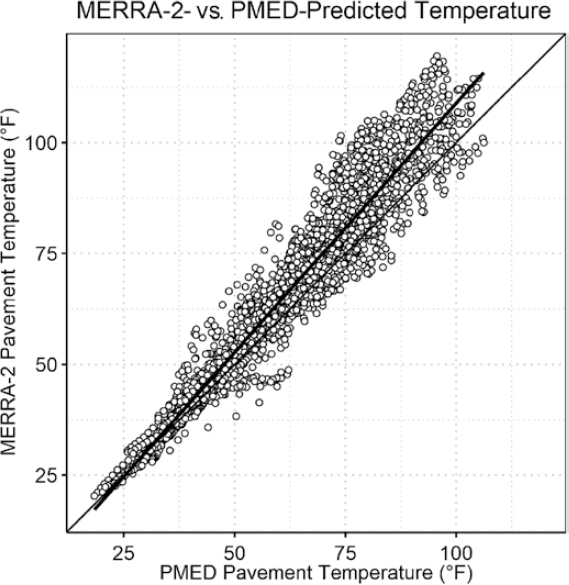

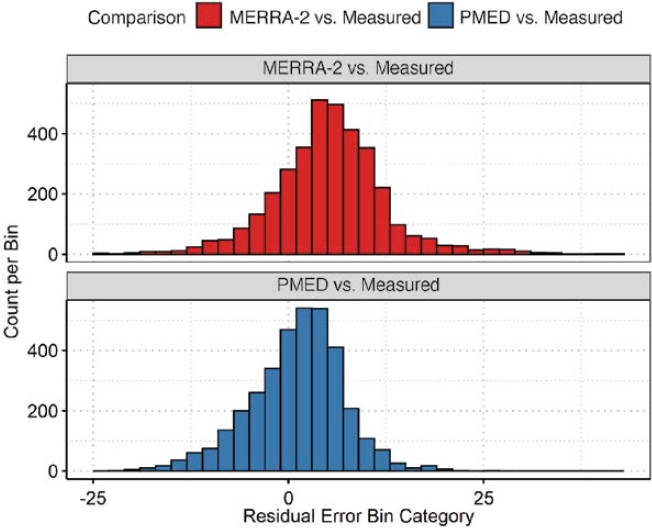

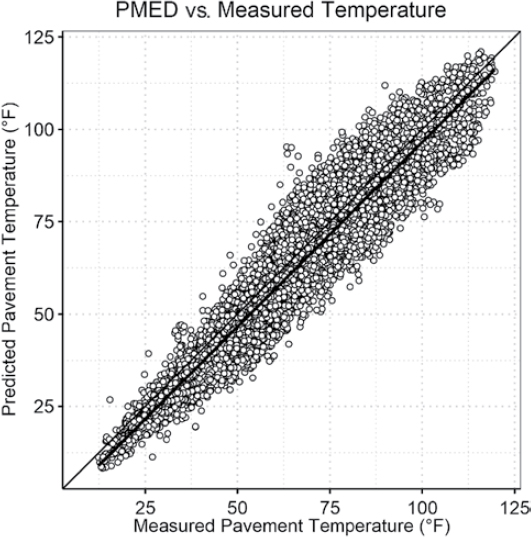

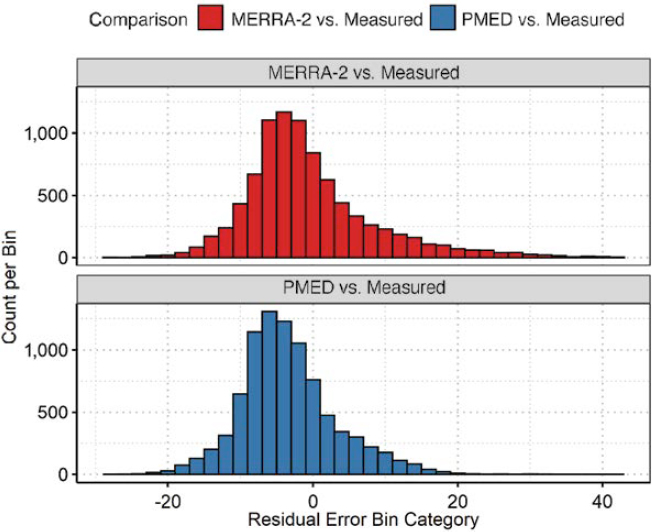

Compare Different Energy Balance Variables to Precipitation and Identify Whether Any Significant Correlations Exist