Breastfeeding in the United States: Strategies to Support Families and Achieve National Goals (2025)

Chapter: 7 Payment and Financing of Breastfeeding Services and Supplies

7

Payment and Financing of Breastfeeding Services and Supplies

How families pay for breastfeeding services and supplies can affect which health care providers, services, and settings are available to them. At the time of this report, health insurance coverage in the United States continues to operate as a complex patchwork system, with state-by-state differences in the payment of perinatal services and breastfeeding support. In addition, several federal and state policies and regulations can affect access to lactation services and supplies across settings, as well as the quality of these services and supplies. These policies also influence the scope of practice for providers and payment for their services.

For a new family, navigating these complex and intersecting systems can be challenging, and lactation support is only one of many new health care supports a new parent may need to access. This chapter focuses on what is known about payment for breastfeeding services and supplies, as well as existing and promising policy and programmatic approaches.

PAYERS: AN OVERVIEW

Coverage or payment for breastfeeding care and supplies in the United States is complex and often opaque to families needing care. Because lactation involves two people, care may be directed toward the mother, the infant, or both. When breastfeeding concerns arise, it may not be obvious whether the family should consult the maternal care provider, the pediatric care provider, both, or a lactation support provider. Furthermore, when the breastfeeding dyad is being seen (e.g., for trouble latching, for neonatal weight loss), assessments and interventions may address both the mother

and the infant and therefore generate health records, including coding and billing, for both individuals. For multiple gestations, three individuals may be involved (e.g., a mother and two infants), and in the case of LGBTQ+ families, there may be two lactating parents and one infant (e.g., two mothers who induce lactation and one infant). Medical records must be generated for each person receiving care, but often only one of the parties may be billed.

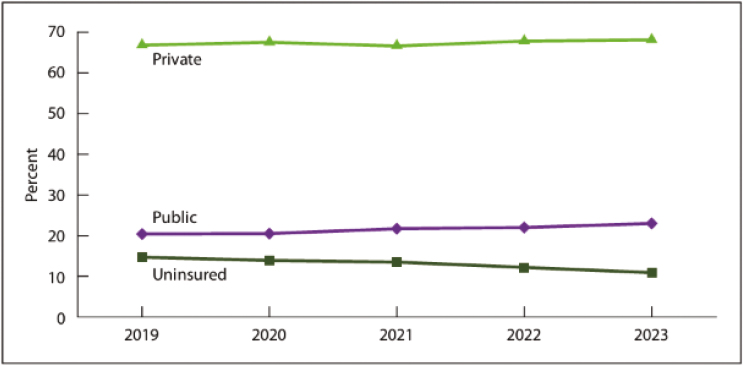

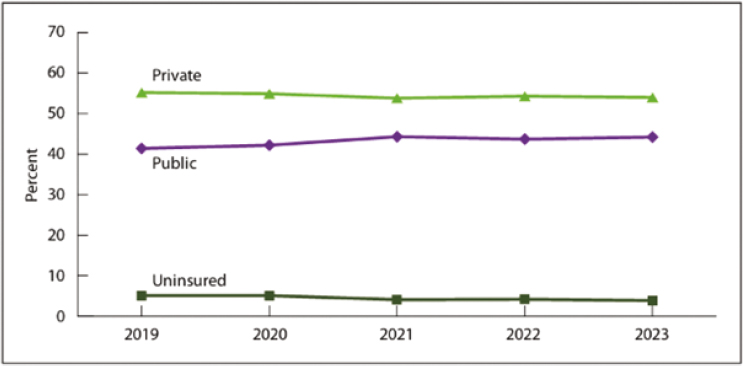

Private health insurance, including employment-based and direct-purchase plans, covered approximately 68.1% of U.S. adults ages 18–64 and 54% of children ages 0-17 years in 20231 (Cohen et al., 2025). Public programs—such as Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE, the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, and Veterans Affairs (VA) coverage—accounted for 23% of adults and 44.2% of children in 2023. The committee notes that while private insurance remains slightly more common among children ages 0–17 years, almost half of U.S. children are covered by public programs such as Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP; Cohen et al., 2025). And as of 2023, 10.9% of adults and 3.9% of children were uninsured. See Figures 7-1 and 7-2 for a visual representation of these differences in health insurance coverage for adults and children in the United States.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 expanded health insurance coverage in the United States, particularly for historically underserved communities (National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, 2024). Prior to its enactment, most individuals obtained coverage through employer-sponsored plans, purchased insurance independently, or qualified for Medicaid based on state-determined income thresholds.

The ACA mandated that all non-grandfathered health insurance plans cover breastfeeding support and supplies, but the specifics of this coverage can vary significantly among insurers; this can contribute to differences in access to lactation services and equipment (National Women’s Law Center, 2015). The Institute of Medicine (2011) recommended that comprehensive lactation support and counseling and the costs of breastfeeding equipment

___________________

1 These estimates are from the National Center for Health Statistics’ 2023 National Health Interview Survey (Cohen et al., 2025). People were described as uninsured if they were not insured through private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), a state-sponsored or other government plan, or a military plan. People were also described as uninsured if they had only Indian Health Service coverage or had only a private plan that paid for one type of service, such as accidents or dental care. Public coverage includes Medicaid, CHIP, state-sponsored or other government-sponsored health plan, Medicare, and military plans. Private coverage includes any comprehensive private insurance plan, including health maintenance and preferred provider organizations. Data are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population (Cohen et al., 2025).

SOURCE: Data from the National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2019–2023; Cohen et al., 2025.

be covered as a preventive service for women, which the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) subsequently adopted as part of the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). Coverage is for “comprehensive lactation support and counseling, including the costs of breastfeeding equipment,

SOURCES: Data from the National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2019–2023; Cohen et al., 2025.

to ensure the successful initiation and continuation of breastfeeding” (National Women’s Law Center, 2015, p. 7).

However, some insurance companies impose restrictions, do not have a network of lactation support providers, or impose administrative barriers or insufficient coverage that prevent mothers from obtaining appropriate and timely lactation support and adequate equipment, all of which undermines and violates the intent of the ACA (National Women’s Law Center, 2015; U.S. Breastfeeding Committee [USBC], 2022). Payment for breastfeeding services and supplies is difficult for insurers to incorporate into existing health care delivery models because billing for payment typically requires a diagnosis code, and breastfeeding is a normal, physiological behavior. In addition, the coverage of lactation support providers varies by in-network system, geographic proximity limits, and licensure and training requirements. Finally, limitations to access to breastfeeding equipment and supplies (e.g., breast pumps) may make hospital-grade breast pumps or pasteurized donor human milk particularly difficult to access (USBC, 2022).

PRIVATE INSURANCE

Private, or nongovernment-sponsored, insurance includes employer-based insurance, as well as direct-purchase insurance for persons whose employers do not provide insurance or work status does not qualify for employer-sponsored insurance. People who lack employer-sponsored insurance options may access private insurance through the government-sponsored health insurance exchange as part of the ACA.

Private insurance companies make their own rules for what is covered in their plans, unless the state or federal government, as with the ACA, has stipulated that insurance companies must cover certain services. Under the ACA, private health insurance companies are required to cover preventive services, including lactation support, counseling, and breastfeeding equipment (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010; see Box 7-1).

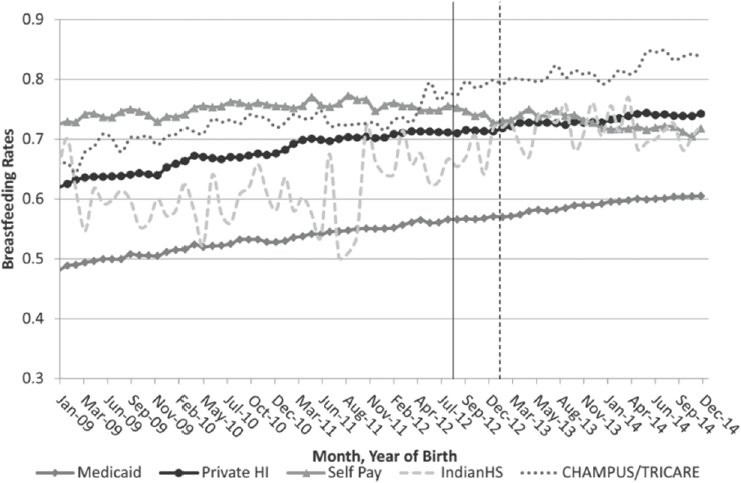

Since the ACA was signed into law, research has shown that its mandate to include lactation support services increased the probability of breastfeeding initiation among privately insured mothers by up to 2.5 percentage points, or approximately 47,000 more infants being breastfed than before, though the true effect may be higher (Kapinos et al., 2017). In addition, Kapinos et al. (2017) found an upward trend in breastfeeding rates of infants at hospital discharge across most payment categories in response to the ACA (see Figure 7-3).

Although breastfeeding initiation rates were consistently lower among births covered by Medicaid compared with those covered by private insurance, the trends before the ACA are parallel. This parallelism suggests that, prior to the ACA’s implementation, breastfeeding indicators were improving

BOX 7-1

Breastfeeding Services and Supplies: Women’s Preventive Services Initiative

Clinical Recommendations:

- Comprehensive lactation support services (including consultation; counseling; education by clinicians and peer support services; and breastfeeding equipment and supplies) during the antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum periods to optimize the successful initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding.

- Breastfeeding equipment and supplies include, but are not limited to, double electric breast pumps (including pump parts and maintenance) and breast milk storage supplies. Access to double electric pumps should be a priority to optimize breastfeeding and should not be predicated on prior failure of a manual pump. Breastfeeding equipment may also include equipment and supplies as clinically indicated to support dyads with breastfeeding difficulties and those who need additional services.

Implementation Considerations:

- Lactation support services include consultation, counseling and psychosocial support, education, breastfeeding equipment, and supplies.

- Lactation support services should be delivered and provided across the antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum periods to ensure successful preparation, initiation, and continuation of breastfeeding.

- Lactation support services should be respectful, appropriately patient centered, culturally and linguistically competent, and sensitive to those who are having difficulty with breastfeeding, regardless of the cause.

- Clinical lactation professionals providing clinical care include, but are not limited to, licensed lactation consultants, the International Board Certified Lactation Consultant®, certified midwives, certified nurse-midwives, certified professional midwives, nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and physicians.

- Lactation personnel providing counseling, education or peer support include lactation counselors/breastfeeding educators and peer supporters.

- Clinical trials of interventions including at least five in-person visits across antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum periods to promote and support breastfeeding showed benefit, but more visits may be required, including psychosocial counseling for breastfeeding.

SOURCE: Excerpted from Women’s Preventive Services Initiative, 2023, p. 20.

NOTES: Vertical lines represent the legislative implementation (August 2012) and likely effective implementation at the modal plan start month (January 2013) dates. N = 24,005,896 births. CHAMPUS = Civilian Health and Medical Program of Uniformed Service; Indian HS = Indian Health Service.

SOURCE: Data from the National Vital Statistics Survey, 2009–2014; Kapinos et al., 2017.

at similar rates across these groups, despite the existing gap in initiation levels. The mandate had the largest impact on communities with historically low rates of breastfeeding, including Black mothers, mothers with a high school education, and mothers who were unmarried (Kapinos et al., 2017).

Although the ACA has improved the likelihood of breastfeeding initiation, challenges remain within the current system. These include the complexity of insurance plans; a lack of transparency; differences in coverage for breastfeeding and lactation care; and financial barriers, such as high premiums, out-of-pocket costs, and uncovered services. The following sections address challenges specifically related to payment for breastfeeding services and coverage for breastfeeding equipment and supplies.

Private Insurance Payment for Breastfeeding Services

In a review of coverage policies in 15 state marketplaces, the National Women’s Law Center (2015) found that many women were unable to access breastfeeding services. Obstacles included limitations on support and

supplies, lack of available in-network providers, and administrative barriers to accessing support. Moreover, some support providers require fee for service at the time of service (USBC, 2022), despite the ACA mandate for coverage; often, this is because of various insurer requirements, such as licensure. Such fee-for-service lactation support might be out of reach for families with economic challenges.

For instance, some insurers list maternity providers and pediatricians as in-network lactation providers, not recognizing that most physicians receive minimal training in breastfeeding (see Chapter 6). Others cover only lactation support providers who are “otherwise licensed”—for example, as a nurse or registered dietitian. This practice excludes most lactation support providers, despite their having completed breastfeeding-specific training (USBC, n.d.), and excludes these individuals from payment and career development. Even when a lactation support provider is recognized as in network, payment for services is complex. The WPSI notes that antenatal lactation support and counseling are considered part of routine care, so these services are often included within the global obstetric professional package, a fixed capitated rate for pregnancy and delivery calculated based on normal, healthy conditions (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2023). After birth, some payers will reimburse visits for preventive medicine counseling in addition to the global obstetric package. Care for breastfeeding problems, such as mastitis or a breast abscess, may be billed as an outpatient problem visit (National Women’s Law Center, 2015).

The WPSI Coding Guide (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2023) outlines several pages of mechanisms for billing for services of advanced practice providers, lactation consultants, and nonclinical staff, noting, “It is advisable to check with specific payers for their specific policies and to obtain those instructions in writing” (p. 2; see Box 7-2). For example, a web page for an outpatient lactation clinic in Texas provides patients with similar advice:

The Affordable Care Act requires insurance companies to fully cover lactation services without limit and without cost sharing. However, your insurance company may apply a co-pay or co-insurance to your visit, put a portion of your visit cost toward your deductible, or limit the number of visits you may receive due to variations in their interpretations of the Affordable Care Act. (McGovern Medical School, n.d., “Important Note” section, para. 1)

This patchwork of payment policies disincentivizes health care facilities from offering lactation services, removes opportunities for lactation support providers to be paid for their services, and places an undue burden on mothers and families who may be struggling to meet their

BOX 7-2

Billing for Breastfeeding Services and Supplies: Women’s Preventive Services Initiative

ICD-10-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification) is a standardized coding system used to classify diseases and medical conditions. Health care providers use these codes for diagnosing patients and recording morbidity data (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024). The Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2023) provides guidance related to specific billing codes to use for payment for breastfeeding or lactation support services or supplies.

Billing for Lactation Services

- Postpartum care: Lactation counseling is typically bundled into postpartum care. Only issues related to complications, illness, or disease can be billed separately.

- Antepartum counseling: Depending on the insurer, lactation counseling during pregnancy may be billed separately from the global obstetrics package.

- Breastfeeding support by physicians and nonphysician lactation support providers:

- - If both a physician and lactation counselor provide care, a single evaluation and management (E/M) code is used.

- - If only a licensed lactation counselor (e.g., nurse practitioner, physician assistant) provides care, E/M code 99211 may be used.

- - For breastfeeding complications requiring physician evaluation, codes 99202–99205 (new patients) or 99212–99215 (established patients) are used.

Group and Preventive Counseling

- Preventive medicine counseling codes 99401–99404 cover lactation support based on time spent.

- Group breastfeeding education can be billed using codes 98961–98962 or 99411–99412.

Follow-Up and Behavioral Health Services

- Nonclinical staff may provide follow-up support under health behavior assessment codes (96156–96171), though insurance coverage varies.

Billing for Breastfeeding Equipment or Supplies

- Insurers that cover lactation equipment may reimburse for breast pumps under supply codes E0602–E0604.

- Replacement parts for breast pumps are billed using A4281–A4286.

ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Codes

- Common breastfeeding-related diagnoses include infections (O91.02, O91.03), abscesses (O91.12, O91.13), mastitis (O91.22, O91.23), nipple issues (O92.03, O92.13), and lactation difficulties (O92.3–O92.79).

- The general encounter code for lactation care is Z39.1.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2023.

breastfeeding goals. This may be because payment for obstetric and neonatal care is bundled whether or not lactation consultants are hired to provide breastfeeding and lactation support services prenatally, at the time of delivery, or during the postpartum period.

Private Insurance Payment for Breastfeeding Equipment and Supplies

Mothers may choose to express their milk for a variety of reasons (e.g., their own comfort, to reduce engorgement, to increase milk supply, or to provide human milk for their baby if they are separated; Buchko, 1994; Chapman et al., 2001; Geraghty, 2012; Meserve, 1982; Nicholson, 1985; Rasmussen & Geraghty, 2011). Nardella et al. (2024) report that breast pump use is associated with longer duration of breastfeeding, with the greatest magnitude of this association found among non-Hispanic Black and Native American mothers. The options for families to acquire breast pumps vary by private insurer, and the number and type of breast pumps available for new families to choose from has dramatically increased, so much so that new families may be confused about how to discern which pump is right for their infant feeding goals and rely on online sources or their health care practitioner to choose one (Becker et al., 2016). One size does not fit all, and there is considerable heterogeneity in milk output among electric pumps (Kapinos et al., 2018). And despite having access to pumps through durable medical equipment (DME) supply companies, families may not be educated adequately on how to use the pump correctly. For example, they may have to learn through product information rather than skilled support and assistance.

Timely delivery of breast pumps through DME providers is critical to supporting successful breastfeeding initiation and continuation, particularly for mothers separated from their infants because of medical complications or returning to work soon after birth. Parker et al. (2012) and

Meier et al. (2008) have noted that initiating milk expression within the first hour postpartum increases milk volume and the likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks and beyond. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (ABM) recommend early and frequent milk removal, especially when infants are unable to nurse directly (e.g., see Eglash et al., 2017). However, access barriers such as delayed DME authorization, limited supply networks, and insurance-related bottlenecks often prolong pump delivery by days, particularly for Medicaid recipients (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2016). These delays may impact early lactation windows, especially for low-income or medically vulnerable populations.

In the United States, breast pumps are currently regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA; 2023) as medical devices. However, issues with the safety and effectiveness of these devices remain, and mothers may experience adverse effects such as injury or breast tissue damage if provided with an inappropriate pump or not instructed on proper use (Becker et al., 2016). Mothers may file a voluntary report with the FDA (2018) if they become injured or experience an infection from a breast pump, but many families do not know about this mechanism.

Although not a prerequisite for breastfeeding success, the ACA mandates that single-user, double electric breast pumps be provided by insurers as DME. Breast pumps can be provided based on three criteria: the ability of the pump to mimic the infant breastfeeding directly, the stage of lactation, and the degree of pump dependency (Meier et al., 2016). However, insurers may not provide electric pumps unless deemed medically necessary2 (e.g., Anthem Blue Cross, Blue Shield, 2025). Other supplies include appropriately sized flanges and storage supplies.

Electric double pumps that are often used in the hospital may be referred to as “hospital grade” and can involve multiple users, can pump both breasts simultaneously, or are typically not portable and are used for mothers in hospital settings (e.g., for feeding premature infants); however, this term is not currently recognized by the FDA (2021). These pumps may be most effective for those mothers who are pump dependent and in the early stages of lactation, such as those mothers with infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (Spatz & Edwards, 2016). For mothers who have been breastfeeding directly and need to pump for separation issues such as return to work or school, a portable double electric pump is typically sufficient for milk expression. A lactation support provider can help to ensure proper fit of the flanges, appropriate pump pressures, and cycling speeds that are most effective for the person using them.

___________________

2 An electric breast pump is not considered medically necessary in the absence of ongoing breastfeeding or when established criteria are not met.

PUBLIC INSURANCE

Public insurance supports for the breastfeeding dyad described below are provided through Medicaid, the U.S. military health system, and the Indian Health Service. Breastfeeding supports may also be covered for the infant through CHIP.

Medicaid

Medicaid, administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), is a joint federal–state program that provides health coverage to low-income individuals. States participate voluntarily but must adhere to federal guidelines. Initially linked to cash assistance programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Medicaid eligibility criteria has evolved over time, particularly for pregnant women, children, and people with disabilities. The 1996 welfare reform law severed Medicaid eligibility from cash assistance, and in 1997, CHIP was established to cover children from low-income backgrounds above Medicaid income thresholds (Rudowitz et al., 2024).

Medicaid Expansion

The ACA significantly reshaped Medicaid, allowing states to expand coverage to nearly all nonelderly adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level. However, a 2012 Supreme Court ruling made this expansion optional, leading to variation in coverage across states. States are required to cover breast pumps and consultation services for Medicaid expansion beneficiaries under the ACA’s preventive services requirement. For nonexpansion states, there is no federal requirement for coverage of breastfeeding services (Ranji et al., 2021).

Medicaid coverage for pregnant women has expanded through various policy changes. The ACA mandated benefits including tobacco cessation programs and birth center services, and some states now reimburse for doula services to improve maternal health outcomes. The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically influenced Medicaid enrollment and funding; for example, telehealth services were expanded, improving access to prenatal and postpartum care, particularly in rural areas (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2023). Federal legislation mandated continuous Medicaid coverage in exchange for enhanced funding, leading to significant enrollment increases and a reduction in the uninsured rate. However, the expiration of these provisions in April 2023 has led to disenrollments, likely reversing some of these gains (Rudowitz et al., 2024).

To date, 40 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the Medicaid expansion, and 10 states have not adopted the expansion.

Hawkins et al. (2022) described the impacts of the ACA and Medicaid expansion on breast pump claims and breastfeeding rates among women with different insurance. A significant increase in insurance claims for breast pumps followed the implementation of the ACA, indicating an increase in access to breastfeeding supports (Hawkins et al., 2022). In addition, the authors noted an increase in breastfeeding initiation and duration among public insurance recipients, suggesting that the policy change and expansion positively influenced breastfeeding practices across insurance type (Hawkins et al., 2022).

Given the expansion in most states and retained coverage for pregnant women and parents, breastfeeding preventive services is a natural fit through Medicaid. In states that have not expanded Medicaid, large gaps in coverage remain between income eligibility and those that qualify for marketplace subsidies, leaving millions without coverage.

Medicaid Extension

In 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act allowed states to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage from 60 days to 12 months postpartum, providing more comprehensive care for new mothers (Kaiser Family Foundation [KFF], 2025a). Before this was enacted, many low-income mothers lost their health coverage after 60 days, which significantly limited their ability to receive health care, including lactation services and supplies. This new option took effect on April 1, 2022, and was originally available for five years; however, the option was made permanent by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023. CMS released guidance on how states could implement this option; since then, 48 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the full extension (KFF, 2025a). In addition, many professional organizations—including the AAP; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; American Medical Association; Association of Women’s Health, Obstetrics, and Neonatal Nurses; American College of Nurse-Midwives; and other leading authorities—have publicly supported the extension of Medicaid coverage (CMS, 2023).

While direct research linking Medicaid extension to breastfeeding rates is limited because of the recency of the extension, extending postpartum Medicaid coverage to 12 months is anticipated to enhance breastfeeding outcomes by providing continuous access to essential health care services and support.

Medicaid and Breastfeeding Support

Medicaid plays a crucial role in maternity care, covering over 40% of births nationwide and the majority in several states (CMS, 2024a). States have

considerable flexibility in determining income eligibility, defining maternity services, and implementing utilization controls such as prior authorization and preferred drug lists. While benefits may vary based on eligibility, most states provide the full Medicaid package to pregnant individuals, often through managed care organizations that may differ in specific service coverage. Additionally, states influence access to maternity care through reimbursement policies, frequently using bundled payments that cover prenatal, labor, and postpartum care, as noted above. While bundled payments help manage costs and promote coordinated care, they can also make it challenging to track individual services such as health education or counseling.

Medicaid eligibility is based on household income, family size, and state of residence, with states in the Southeast generally setting lower income caps than those in the Northeast and California, leaving many uninsured (further discussion on uninsurance follows). Most Medicaid programs are administered through private insurance companies with negotiated rates and coverage plans, often offering benefits that are more limited than those in employer-sponsored plans. In rare cases, mothers may qualify for Medicare if they have a permanent disability or a qualifying condition, such as end-stage renal disease.

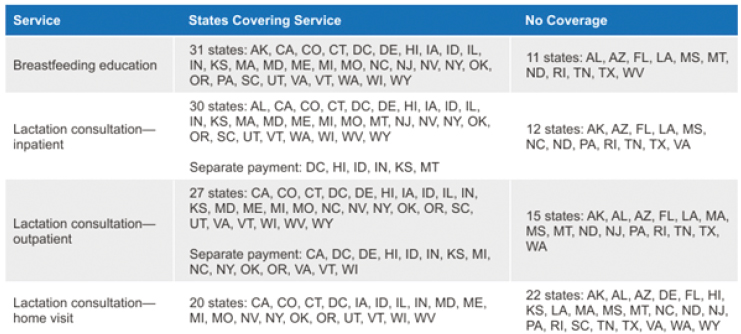

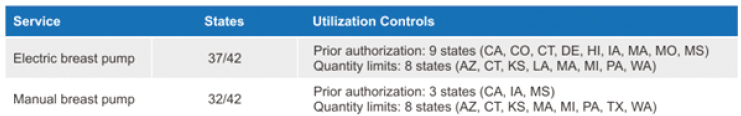

For women with Medicaid coverage, lactation service and supply coverage are determined by each state’s Medicaid policy. States cover lactation support services and breast pumps under the ACA’s preventive services requirements. However, states that have not expanded Medicaid are not federally required to cover lactation support services (Ranji et al., 2022). Figures 7-4 and 7-5 present state Medicaid coverage for lactation support (i.e., breastfeeding services) and breast pumps, respectively. Data are

SOURCE: Ranji et al., 2022. Licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0.

SOURCE: Ranji et al., 2022. Licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0.

included from responding states, and the tables do not capture coverage of all states and territories.

Innovative Efforts

Some states—Massachusetts, California, and Illinois—are taking further steps to provide the Medicaid extension to mothers, regardless of their immigration status. In addition, other states report that they are considering adding doula services to covered benefits, include initiatives to address mental health services for their beneficiaries, and adopt provider performance measures (Ranji et al., 2022).

Conclusion 7-1: Medicaid expansion has positively influenced breastfeeding rates by increasing access to prenatal education, postpartum lactation support, breast pumps, and maternal health care. The extension of postpartum Medicaid coverage from 60 days to 12 months is promising, as it may help mothers with low incomes sustain breastfeeding beyond the initial few weeks postpartum. By reducing barriers to access critical services, Medicaid expansion and extension efforts not only improve maternal and infant health outcomes but also may promote higher breastfeeding initiation and duration rates among low-income populations.

Recommendation 7-1: The U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should continue to ensure that postpartum Medicaid extension is available to all eligible pregnant and postpartum women up to 12 months after birth, at a minimum; all states should implement this option.

In 2023, the Consolidated Appropriations Act made permanent the state plan option to provide 12 months of postpartum coverage in Medicaid and CHIP. States enacting this option are required to provide 12 months of continuous eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP enrollees under the age of 19, starting January 1, 2024. However, if states choose not to implement the extension, it could lead to coverage gaps for postpartum mothers, with negative effects.

U.S. MILITARY HEALTH SYSTEM

The U.S. military health system comprises two arms: health care provided by active-duty providers and facilities through the military, such as in VA hospitals, and health care provided by civilian facilities and providers through the military insurance program TRICARE.

Breastfeeding counseling, breast pumps, and other related supplies are provided to TRICARE (2024a) beneficiaries at no cost. TRICARE (2024b) covers breastfeeding counseling (a) during an inpatient maternity stay, follow-up outpatient visit, or well-child visit or (b) as part of up to six separate outpatient sessions when counseling is the only service provided, deemed and billed as a preventive service or provided by an authorized provider. Mothers may select a breast pump and receive a prescription from a TRICARE-authorized physician, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or nurse midwife; this differs from other insurance providers (TRICARE, 2024a). If they first purchase the pump through an approved provider, they must file reimbursement through a claims system, which pays a set amount of a breast pump (TRICARE, 2024a). In order to receive a hospital-grade pump, the mother must receive a referral from their health care provider and regional contractor (TRICARE, 2024a). The children of parents who are not active-duty service members but are covered by TRICARE must be registered in the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System during their first 90 days of life. If not registered, families will be denied claims after the child is 91 days old (TRICARE, 2024c).

In April 2024, the Department of Defense enacted the Extra Medical Maternal Health Providers Demonstration project, which requires the Secretary of Defense to provide an annual report on an extra medical maternal health provider demonstration, which the Department has titled the Childbirth and Breastfeeding Support Demonstration (CBSD). The CBSD began January 1, 2022, and is set to expire on December 31, 2026, with overseas implementation beginning January 1, 2025 (U.S. Department of Defense, 2024).

Additional outpatient visits (beyond the six traditionally covered by TRICARE with lactation consultants or additional care provided by doulas or other breastfeeding and lactation support providers may be approved depending on circumstances under the new CBSD. To date, there are no publicly available evaluations of the CBSD.

INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE

The Indian Health Service (IHS) is an HHS agency responsible for providing federal health care services to Native American individuals. After a determination of eligibility, patients can access any IHS facility and

participating provider. In addition, Native American individuals or families may access health care through the tribal health system. Tribes can establish agreements with the IHS to access care in traditional facilities and by non-IHS providers within the tribal health system. In 2020, the IHS reported that it provided health care services to over two million members of 567 federally recognized tribes (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020).

CHILDREN’S HEALTH INSURANCE PLAN (CHIP)

Breastfeeding care and supplies also involve pediatric services. Children are covered through health insurance independent of their parents and may sometimes be on completely different plans. In 1997, Congress enacted the States Children’s Health Insurance Act. The plan, now called CHIP, was made permanently through the ACA in 2010 (Racine et al., 2014). In 2020, 48% of all U.S. children ages 0–18 years were covered by Medicaid and CHIP (KFF, 2025b).

The 2017 fourth edition of Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents specifically recommends breastfeeding and lactation services as required coverage by all plans (Hagan et al., 2017). Bright Futures is an AAP publication, supported by HRSA; it includes theory-based, evidence-driven, and systems-oriented principles, strategies, and tools for improving the health and well-being of all children, focusing on culturally appropriate interventions that address current and emerging needs at the family, clinical practice, community, health system, and policy levels. The Bright Futures principles acknowledge the value of each child, the importance of family, the connection to community, and that children and youth with special health care needs are children first. The AAP updates its recommendations in Bright Futures regularly and in collaboration with HRSA, including the recommendations for periodicity of well visits. Breastfeeding is included in the Bright Futures guidelines as integral to preventive health care for children.

Bright Futures recommends covering preventive care such as breastfeeding management, consultation, and support to increase the initiation, exclusivity, and duration of breastfeeding, both in the birth hospital and after discharge in the ambulatory setting (Hagan et al., 2017). It does not, however, specify the type of provider or training necessary to carry out breastfeeding management, consultation, and support. For example, Bright Futures assumes the pediatrician can provide the services described. But, as discussed previously, most pediatricians have inadequate education and training to do so (Feldman-Winter et al., 2017).

CONSIDERATIONS RELATED TO UNINSURED POPULATIONS

Among high-income nations, the United States has the highest percentage of individuals without health insurance: 8% of the total population (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2024; Tolbert et al., 2024). The rate of uninsurance stands at 20.9% for Hispanic individuals, 10.4% for Black (non-Hispanic) individuals, 6.4% for White (non-Hispanic) individuals, and 6.5% for Asian (non-Hispanic) individuals; the rate for all groups categorized as “other” is 8.4% (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2024). The experience of these vulnerable families who are unable to access care may not be reflected in overall trends and performance (Schneider et al., 2021).

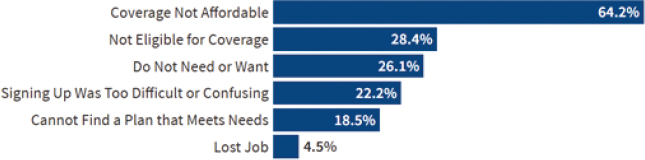

In addition, administrative barriers to accessing health insurance and health services may disproportionately deter families who are historically underserved from accessing the care they need (Schneider et al., 2021). For example, mothers or families may experience difficulties navigating insurance eligibility rules and application procedures because of the complexity and high burden of these current processes. High out-of-pocket costs may also serve as a deterrent to receiving lactation support and services, or families may not have access to the information they need to access these critical services (see Figure 7-6).

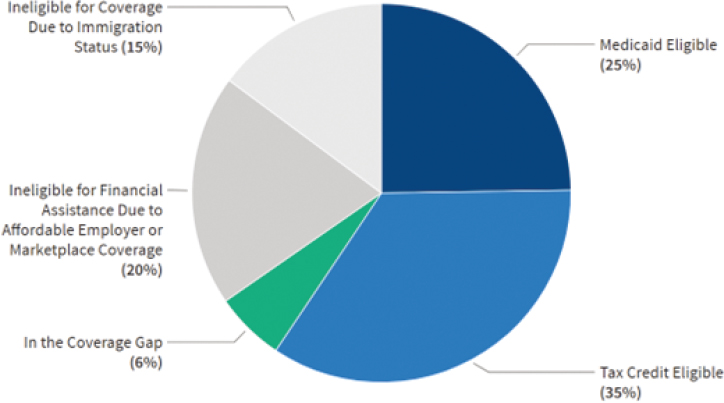

In the ten states that have not adopted the Medicaid expansion (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming), approximately 1.5 million people remain uninsured, or fall in a “coverage gap,” without options for affordable coverage (Tolbert et al., 2024). In addition, many workers may lack access to employer-sponsored health coverage and continue to face constraints related to high costs; many low-income families spend a larger proportion of their income on high premiums and medical expenses, compared with higher-income families. Lawfully present immigrants face 5-year waiting

SOURCE: Tolbert et al., 2024. Licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0.

SOURCE: Tolbert et al., 2024. Licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0.

periods to qualify for Medicaid, though state coverage may cover mothers and children (Tolbert et al., 2024). And they may also experience fear that they may be deemed a “public charge” and avoid seeking coverage (Kearney et al., 2024). Therefore, while financial assistance may be available under the ACA or through programs at the state level, many families may continue to be uninsured because of these gaps in Medicaid expansion, employer coverage, or immigration status (Figure 7-7).

Many health systems offer care to uninsured mothers and families by hosting free clinics and sliding scales for payment, and even by waiving payments for certain types of care. Such health systems, often referred to as “safety net” hospitals or health systems, sometimes receive subsidies from the states where they are located for providing such care. In addition, states, including some that have no expanded Medicaid, have led efforts to broaden access to insurance. As of 2024, several states have extended fully state-funded coverage to low-income individuals regardless of immigration status; 12 states and Washington, DC, cover children regardless of status, and five states and Washington, DC, cover some adults regardless of status. Additionally, nearly all states have extended Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months, and many are using waivers to ensure continuous eligibility for children and some adults, allowing them to stay enrolled regardless of income changes (Tolbert et al., 2024).

PROMISING APPROACHES FOR PAYERS

In 2022, the USBC (2022) Lactation Support Providers Constellation noted that limitations of covered services, covered providers, and access to equipment and supplies have reduced the impact of the ACA’s lactation coverage. Limitations include a lack of incentive to increase breastfeeding rates at discharge or during the postpartum period, as there is no benefit tied to the provision of this care because it is not paid for separately (USBC, 2022). In addition, with the move to shift the Perinatal Care Core Measure 05a and 05 to an incentive-based system, hospitals are no longer required to monitor their rates of breastfeeding. To address these limitations, the

BOX 7-3

Proposed Payer Solutions from the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee

Expand Access to Community-Based Breastfeeding Support

- Health plan membership model: Health plans can fund memberships in community breastfeeding organizations, similar to fitness club voucher programs.

- Financial support for volunteer organizations: Families receive a voucher covering membership dues or donations, helping sustain organizations offering breastfeeding peer counseling.

- Access to flexible support: Families are not restricted to one organization, ensuring broad access to phone support, telehealth, support groups, and in-person visits.

Infant Nutrition Security Payment Model

- Streamline lactation support provider verification

- - Employ Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare (CAQH) credentialing to register and verify trained lactation support providers

- - Have training organizati ons assist in the verification of lactation support provider qualifications

- - Centralize verification of lactation support providers to expand access to culturally competent breastfeeding care

- Create a lactation service superbill

- - This would be a standardized billing form based on the time and complexity of the care provided.

- - Lactation support providers could submit a claim directly to health insurers for reimbursement, after they are verified by CAQH.

- - It could increase access to trained lactation support providers and ensure that appropriate referrals are made for complex issues.

SOURCE: USBC, 2022.

USBC (2022) outlined key recommendations regarding duration, frequency, and site of lactation support services, as well as recommended coverage for equipment and supplies (Box 7-3).

The USBC (2022) further notes that existing ACA coverage does not support community-based organizations that provide culturally congruent and responsive peer support. USBC (2022) instead proposes that insurers provide pregnant and parenting families with a membership voucher, which they can award to a local community-based breastfeeding organization to offset operating costs. For billing purposes moving forward, it will also be important to better estimate the costs associated with providing a range of services that may be required for optimal care throughout the lactation journey, using sound econometric models (e.g., Arslanian et al., 2022; Carroll et al., 2020).

Conclusion 7-2: Inconsistencies in insurance coverage can hinder mothers from receiving standard, high-quality, and timely health care, which can affect breastfeeding initiation and duration rates. Clear guidelines; uniform enforcement of coverage requirements; and communication among health care providers, insurers, and members of the public could all help to address these variances and ensure that all mothers have equal access to essential lactation support services and supplies.

Recommendation 7-2: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Federal Insurance Office, in collaboration with public and private payers, should create and ensure comprehensive coverage and payment of breastfeeding services and supplies to guarantee equal access to a standard package of services and durable medical equipment.

Health insurance coverage for families is critical, as it ensures that mothers and their children have access to essential medical care. This coverage before and during pregnancy and postpartum can help prevent birth complications, support breastfeeding, and provide essential newborn care, all of which set a strong foundation for lifelong health (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2024).

CMS and the Federal Insurance Office (FIO) are key actors for collaborating with public and private payers to identify strategies for improving comprehensive coverage and payment of breastfeeding services and supplies. CMS oversees and regulates some private health insurance, along with Medicaid; within CMS (2024b), the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight oversees many of the reforms in the ACA related to private health insurance. In addition, under Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, the FIO in the U.S. Department of the Treasury (n.d.) has the authority to “monitor all aspects of the insurance sector” (para. 1).

REFERENCES

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2023). Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) 2023–2024 coding guide. https://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/WPSI_CodingGuide_2023-2024-FINAL.pdf

Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield. (2025). CG-DME-35: Electric breast pumps (clinical UM guideline). https://www.anthem.com/medpolicies/abcbs/active/gl_pw_c164437.html

Arslanian, K. J., Vilar-Compte, M., Teruel, G., Lozano-Marrufo, A., Rhodes, E. C., Hromi-Fiedler, A., García, E., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2022). How much does it cost to implement the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative training step in the United States and Mexico? PLoS One, 17(9), e0273179. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273179.

Becker, G. E., Smith, H. A., & Cooney, F. (2016). Methods of milk expression for lactating women. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9(9), CD006170. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006170.pub5

Buchko, B. L., Pugh, L. C., Bishop, B. A., Cochran, J. F., Smith, L. R., & Lerew, D. J. (1994). Comfort measures in breastfeeding, primiparous women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 23(1), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.1994.tb01849.x

Carroll, G., Safon, C., Buccini, G., Vilar-Compte, M., Teruel, G., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2020). A systematic review of costing studies for implementing and scaling-up breastfeeding interventions: what do we know and what are the gaps? Health Policy Plan, 35(4), 461–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa005

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). ICD-10-CM: Classification of diseases, functioning, and disability. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd-10-cm/index.html#:~:text=Introduction,medical%20conditions%20(morbidity)%20data

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). (2023). Examining rural telehealth during the public health emergency. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/examining-rural-telehealth-jan-2023.pdf

———. (2024a). 2024 maternal health at a glance. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/downloads/2024-maternal-health-at-a-glance.pdf

———. (2024b). Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight (CCIIO). https://www.cms.gov/cciio

Chapman, D. J., Young, S., Ferris, A. M., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2001). Impact of breast pumping on lactogenesis stage II after cesarean delivery: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatrics, 107(6), E94. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.6.e94

Cohen, R. A., Briones, E. M., & Sohi, I. (2025). Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2024 (Early release; pp. 1–29). National Center for Health Statistics. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc/170372

Eglash, A., Simon, L., & The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. (2017). ABM clinical protocol #8: Human milk storage information for home use for full-term infants (Revised). Breastfeeding Medicine, 12(7), 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2017.29047.aje

Feldman-Winter, L., Szucs, K., Milano, A., Gottschlich, E., Sisk, B., & Schanler, R. J. (2017). National trends in pediatricians’ practices and attitudes about breastfeeding: 1995 to 2014. Pediatrics, 140(4), e20171229. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1229

Geraghty, S., Davidson, B., Tabangin, M., & Morrow, A. (2012). Predictors of breastmilk expression by 1 month postpartum and influence on breastmilk feeding duration. Breastfeeding Medicine: The Official Journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, 7(2), 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2011.0029

Hagan, J. F., Shaw, J. S., & Duncan, P. M. (Eds.). (2017). Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents (4th ed.). American Academy of Pediatrics.

Hawkins, S. S., Horvath, K., Noble, A., & Baum, C. F. (2022). ACA and Medicaid expansion increased breast pump claims and breastfeeding for women with public and private insurance. Women’s Health Issues, 32(2), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2021.10.005

Institute of Medicine. (2011). Clinical preventive services for women: Closing the gaps. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13181

Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). (2025a). Medicaid postpartum coverage extension tracker. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/medicaid-postpartum-coverage-extension-tracker/

———. (2025b). Medicaid enrollment and unwinding tracker. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/medicaid-enrollment-and-unwinding-tracker/

Kapinos, K. A., Bullinger, L., & Gurley-Calvez, T. (2017). Lactation support services and breastfeeding initiation: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act. Health Services Research, 52(6), 2175–2196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12598

Kearney, A., Schumacher, S., Pillai, D., Artiga, S., & Hamel, L. (2024). Five key facts about immigrants’ understanding of U.S. immigration laws, including public charge. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/poll-finding/five-key-facts-about-immigrants-understanding-of-u-s-immigration-laws-including-public-charge/

McGovern Medical School. (n.d.). Insurance coverage for lactation services. Lactation Foundation. https://med.uth.edu/lactation-foundation/insurance-coverage-for-lactation-services/

Meier, P. P., Engstrom, J. L., Janes, J. E., Jegier, B. J., & Loera, F. (2008). Breast pump suction patterns that mimic the human infant during breastfeeding: greater milk output in less time spent pumping for breast pump-dependent mothers with premature infants. Journal of Perinatology, 28(7), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2008.19

Meier, P. P., Patel, A. L., Hoban, R., & Engstrom, J. L. (2016). Which breast pump for which mother: An evidence-based approach to individualizing breast pump technology. Journal of Perinatology, 36(7), 493–499. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.14

Meserve, Y. (1982). Management of postpartum breast engorgement in non-breastfeeding women by mechanical extraction of milk [Abstract]. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery, 27, 3–8.

Nardella, D., Canavan, M., Sharifi, M., & Taylor, S. (2024). Quantifying the association between pump use and breastfeeding duration. The Journal of Pediatrics, 274, 114192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2024.114192

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2024). Ending unequal treatment: Strategies to achieve equitable health care and optimal health for all. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27820

National Women’s Law Center (NWLC). (2015). State of breastfeeding coverage: Health plan violations of the Affordable Care Act. https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/State-of-Breastfeeding-Coverage-Health-Plan-Violations-of-the-Affordable-Care-Act.pdf

Nicholson, W. L. (1985). Cracked nipples in breastfeeding mothers: A randomised trial of three methods of management. Nursing Mothers’ Association of Australia, 21(4), 7–10.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Promoting breastfeeding through hospital policy: The Indian Health Service’s Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. Healthy People in Action. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://odphp.health.gov/news/202007/promoting-breastfeeding-through-hospital-policy-indian-health-services-baby-friendly-hospital-initiative#ref5

Parker, L. A., Sullivan, S., Krueger, C., & Kelechi, T. (2012). Timely initiation of milk expression reduces the risk of delayed lactogenesis II in mothers of very low birth weight infants. Journal of Perinatology, 32(5), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2011.116

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2713 (2010). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2010-title42/USCODE-2010-title42-chap157-subchapXXV-sec2713

Racine, A. D., Long, T. F., Helm, M. E., Hudak, M., Committee on Child Health Financing, Shenkin, B. N., Snider, I. G., White, P. H., Droge, M., & Harbaugh, N. (2014). Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): Accomplishments, challenges, and policy recommendations. Pediatrics, 133(3), e784–e793. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-4059

Ranji, U., Gomez, I., Salganicoff, A., Rosenzweig, C., Kellenberg, R., & Gifford, K. (2022). Medicaid coverage of pregnancy-related services: Findings from a 2021 state survey. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Medicaid-Coverage-of-Pregnancy-Related-Services-Findings-from-a-2021-State-Survey.pdf

Ranji, U., Salganicoff, A., & Gomez, I. (2021). Postpartum coverage extension in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/postpartum-coverage-extension-in-the-american-rescue-plan-act-of-2021

Rasmussen, K. M., & Geraghty, S. R. (2011). The quiet revolution: breastfeeding transformed with the use of breast pumps. American Journal of Public Health, 101(8), 1356–1359. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300136

Rudowitz, R., Tolbert, J., Burns, A., Hinton, E., & Mudumala, A. (2024). Health Policy 101: Medicaid. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/health-policy-101-medicaid/?entry=table-of-contents-introduction

Schneider, E., Shah, A., Doty, M., Tikkanen, R., Fields, K., & Williams, R. (2021). Reflecting poorly: Health care in the U.S. compared to other high-income countries. The Commonwealth Fund. https://search.issuelab.org/resources/38740/38740.pdf

Spatz, D. L., & Edwards, T. M. (2016). The use of human milk and breastfeeding in the neonatal intensive care unit: Position statement 3065. Advances in Neonatal Care, 16(4), 254. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000313

Tolbert, J., Singh, R., & Drake, P. (2024). Health Policy 101: The uninsured population and health coverage. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/health-policy-101-the-uninsured-population-and-health-coverage/?entry=table-of-contents-introduction

TRICARE. (2024a). Breast pumps. https://tricare.mil/breastpumps

———. (2024b). Covered services. https://tricare.mil/CoveredServices/IsItCovered/BreastfeedingCounseling

———. (2024c). Expecting a child? Here’s how TRICARE covers maternity services. https://newsroom.tricare.mil/News/TRICARE-News/Article/3751623/expecting-a-child-heres-how-tricare-covers-maternity-services

U.S. Breastfeeding Committee (USBC). (n.d.). Lactation Support Providers constellation. https://www.usbreastfeeding.org/lactation-support-providers-constellation.html

———. (2022). Payer policy guidance: Innovative approaches to coverage of breastfeeding support, equipment, and supplies. U.S. Breastfeeding Committee. https://web.usbreast-feeding.org/External/WCPages/WCWebContent/webcontentpage.aspx?ContentID=2409

U.S. Department of Defense. (2024). Extramedical maternal health providers demonstration project. Reports to Congress. https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Reports/2024/04/24/Extra-Medical-Maternal-Health-Providers-Demo

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (n.d.). Federal insurance office. https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-markets-financial-institutions-and-fiscal-service/federal-insurance-office

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2018). Injury and infection. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/breast-pumps/injury-and-infection

———. (2021). Buying and renting a breast pump. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/breast-pumps/buying-and-renting-breast-pump

———. (2023). What to know when buying or using a breast pump. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/what-know-when-buying-or-using-breast-pump

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2016). Medicaid: CMS should take additional actions to help improve provider and beneficiary experiences with managed care (GAO-16-862). https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-16-862

This page intentionally left blank.