Stormwater Retrofit Programs and Practices Through Third-Party Partnerships (2025)

Chapter: 4 Case Examples

CHAPTER 4

Case Examples

Survey questionnaire responses were reviewed to identify state DOTs that could provide expertise in both retrofit programs and partnership experience. Eighteen state DOTs responded that they had a retrofit program, and 10 of these DOTs with such a program expressed an interest in participating in follow-up questioning. Responses to the survey questionnaire regarding the amount of partnership infrastructure either constructed or operated and maintained (Questions 14 and 15), as well as the DOT’s stated experience with partnerships (Question 18), were used to further narrow the field.

Eight state DOTs were identified as potential case examples, but only four participated in follow-up interviews to discuss their experience with partnerships. Florida does not have retrofit requirements but was selected because they indicated that 11% to 20% of their facilities are operated or maintained through partnerships, which was more than all but one other survey respondent. North Carolina and California both have retrofit requirements in their MS4/TS4 permit language. Rhode Island has retrofit requirements as part of a DOJ consent decree. California and Rhode Island were selected because they were the only two survey respondents that reported having considerable experience with partnerships.

The interviews were structured to identify the motivations for the partnerships and examples of partnership projects. Eight questions were asked of each state, and several state-specific questions were posed to each state based on responses to the original survey questionnaire. The intent of the follow-up questions was to identify techniques the state DOTs used to initiate and manage partnerships, as well as to identify specific partnership projects and detail the experience gained from these projects. The follow-up questions are included in Appendix C.

The subject state DOTs have had the opportunity to review and comment on the case examples.

4.1 Florida

Florida’s partnership program is rooted in a state stormwater regulation that predates the federal NPDES program. This state regulation, known as Environmental Resource Permitting, has existed in some form since the late 1970s and requires treatment for any impervious surface. The Florida DOT (FDOT) is the main stakeholder in several TMDL plans but typically only owns 1% to 2% of a watershed, so these TMDL requirements drive many partnerships with other stakeholders in the remainder of the watershed. FDOT’s MS4 permit does not have a retrofit requirement, so retrofit projects are the result of satisfying either TMDL requirements or state regulations, or an operational decision to cooperate with regional watershed authorities.

In Florida, it is recognized that regional facilities provide increased stormwater treatment effectiveness as well as more cost-effective construction and operation. Most partners are local

governments and share responsibilities in construction, operation and maintenance, and financing in various ways, depending on the project. The Florida DOT prefers that local partners perform maintenance and operation but participates in many partnerships in which that does not occur. In their survey questionnaire responses, the FDOT indicated that 1% to 10% of their facilities were constructed with partners but that 10% to 20% were maintained by partners.

The Florida DOT has found that a regional or watershed approach often works better when a partner that impacts more of the watershed is the lead partner. Again, the department generally only occupies 1% to 2% of a watershed, so they are not often in a position to lead partnerships when the project affects a substantial portion of a watershed. FDOT has always tried to encourage partnerships and historically had a program titled Environmental Look Around, whereby the regional hydraulic engineer would make an effort to identify regional projects and partnerships. The results of this approach too often relied on luck and the force of personality to get partnerships established during final design and construction. A new program that has replaced Environmental Look Around is WATERSS. With WATERSS, there is an effort to systematically identify partnerships at the planning stage and to launch every project earlier.

4.1.1 Florida Signature Partnership Project: Altamonte Springs–FDOT Integrated Reuse and Stormwater Treatment

Altamonte Springs, Florida, is a suburb of Orlando with a population of approximately 47,000. The city’s water reuse system was constructed in the late 1980s. In this system, known as A Prototype Realistic Innovative Community of Today (APRICOT), domestic wastewater is treated and delivered through a separate non-potable distribution network for non-drinking uses, such as irrigation for lawns and landscaping. The APRICOT reuse system serves nearly 1,000 residential and commercial connections using over 80 miles of transmission mains, an elevated half-million-gallon storage tank, and an augmentation surface storage reservoir known as Crane’s Roost.

APRICOT diverts to irrigation approximately 94% of the city’s wastewater effluent. Almost every property in Altamonte Springs is connected to the system to reuse this treated water. Because of the varied seasonal demands upon irrigation and the relatively constant production of domestic wastewater, the system stores a portion of the reclaimed water in the Crane’s Roost facility for use during times of higher irrigation demand. During flood events, Crane’s Roost historically did not have enough capacity to store all the runoff, and such overflows were diverted into the Wekiva River.

Interstate 4, a freeway connecting Orlando with Daytona Beach to the northeast, bisects the City of Altamonte Springs. Historically, runoff from I-4 was directed to drainage ponds along the side of the road, where it would either evaporate or percolate into the ground. Over time, runoff water and associated pollutants would soak into the groundwater. During plans for the redevelopment of I-4, the Florida DOT was faced with the need to construct a retention/infiltration pond over 600 ft from the highway. The pond would require operation and maintenance, as well as the construction of a 96-in. conduit micro-tunneled from the highway to the pond location. However, during plan development, the City of Altamonte Springs approached the Florida DOT with the proposal to divert all I-4 drainage to the Crane’s Roost surface storage/augmentation facility, adjacent to the highway. The project was called Altamonte Springs–FDOT Integrated Reuse and Stormwater Treatment (A-FIRST). The highway runoff would be stored at Crane’s Roost with wastewater effluent and pumped as needed to the city’s treatment facility, where it would augment the city’s existing reclaimed water supply and be used for irrigation. A new pipeline would also be constructed to carry excess flows to the neighboring City of Apopka for reuse irrigation there. By providing a diversion to Apopka, A-FIRST would lessen the need to discharge emergency floodwater into the Wekiva River.

By participating in the A-FIRST project, the Florida DOT’s need for the micro-tunneled conduit, the pond, and associated right-of-way acquisition was eliminated. All I-4 water is now diverted to Crane’s Roost, where it is stored for reuse, and the system has been expanded to take excess flows to the Apopka. Flood diversions from Crane’s Roost into the Wekiva River are reduced, if not eliminated.

A-FIRST is the first partnership of its kind in Florida. FDOT and the City of Altamonte Springs, along with the St. Johns River Water Management District, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, and the City of Apopka all joined as partners on the project. The project cost $12.5 million, with FDOT’s share being $4.5 million; the St. Johns River Water Management District, $3.5 million; the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, $1.5 million; and the City of Altamonte Springs, $3 million, along with ownership and maintenance responsibilities.

A-FIRST had been conceived during the original construction of the APRICOT system in the 1980s but was never completed. Once the concept was reactivated and funding identified, the partnership took about 3 years of active work to complete. The project utilizes and expands upon the existing Altamonte Springs reuse system, providing irrigation water that does not have to be drawn from Florida’s dwindling groundwater aquifer. Additionally, contaminants that might otherwise flow into the groundwater aquifer or the Wekiva River are captured and removed, and the water is converted to beneficial use.

4.1.2 Florida Case Example Summary

At the Florida DOT, the main drivers for retrofit practices in stormwater systems are satisfying TMDL and state requirements, as well as making operational decisions to cooperate with regional watershed authorities, as in the A-FIRST project. The techniques used for these retrofit projects are generally retention facilities, flow-through facilities, detention facilities, and proprietary stormwater treatment. The primary reason FDOT participates in stormwater retrofitting is to cooperate on regional water quality efforts with other agencies or municipalities. The retrofits are not mandated by the DOT’s MS4 permit.

FDOT has implemented the WATERSS process to emphasize a watershed approach to their stormwater program. A guidebook (Florida DOT 2021) outlines the process whereby stormwater projects are scoped and evaluated through a watershed perspective with all stakeholders involved. This process is intended to select projects with a watershed philosophy and to involve potential partners in the site selection, construction, and operation of both partnership and stand-alone Florida DOT facilities.

Florida has gained both positive and negative experiences from their stormwater partnership program. FDOT estimates that between 1% and 10% of their permanent stormwater facilities have been constructed with third-party partners, and between 11% and 20% operated or maintained with such partners. Stormwater partnerships are primarily in urban areas and include municipalities, counties, and special districts. Partnerships are funded by the DOT distributing funds for a partner to construct alone, shared construction and operational efforts, or DOT construction of facilities, with the partner providing other considerations. Funding mechanisms for third parties are highly variable and depend on the project.

Barriers to partnerships include lack of funding from the partner, differing visions of what constitutes a good project, difficulty identifying the lead partner, and agreements forgotten with staff turnover and the passage of time.

Regional facilities are believed to be both less expensive and more effective than onsite facilities. It is also beneficial for FDOT to focus on project development and construction, and to leave the maintenance and operation to another partner.

One of the best benefits to the program is that it generates considerable goodwill with local partners. Florida listed two challenges faced with these partnerships. First, was the complexity they added to the projects. These partnerships contain many moving parts, and the efforts necessary to align various partners’ goals can adversely impact project schedules. Another challenge can occur with regulators. Florida DOT has found that regulators are not as supportive as they might be with creative, innovative partnership approaches that do not fit inside their “regulatory box.”

4.2 North Carolina

Since its first NPDES TS4 permit was issued in 1998, the North Carolina DOT (NCDOT) has been required to construct 70 retrofit projects for every 5-year permit term. The requirement for 70 retrofits is actually a credit program: a large, impactful project might count as several of the 70 retrofit projects, and the number of credits assigned to a single project is determined by a negotiation between NCDOT and its regulator. The first TS4 permits required NCDOT to locate retrofit projects uniformly across the state and construct projects at a pace equal to 14 retrofits per year. These constraints on the locations and pace of construction hampered NCDOT’s ability to partner with third parties on retrofit projects. Subsequent permit renewals have eased some of these constraints but the requirement to construct a total of 70 retrofit credits over the 5-year permit term has remained.

North Carolina’s partnership and retrofit program was transformed by their TS4 permit renewal in 2022, which removed the requirement that retrofits must treat NCDOT runoff. This change has invigorated the agency’s efforts to identify partnerships and deliver projects through these partnerships. Most of these partnerships have shared responsibilities, with the DOT ideally working on the design and construction, and the partners taking over maintenance and operations. There are some new efforts to establish cash in lieu of NCDOT’s participation, but these efforts have been only recently initiated. The partnerships are located throughout the state, with frequent partners being large cities and the North Carolina Coastal Federation, a non-profit advocacy organization. With the necessity for NCDOT to develop 70 project credits over the 5-year life of the permit, the partnerships reach nearly every corner of the state. Some critical watersheds with nutrient-loading issues see considerable attention.

4.2.1 North Carolina Signature Partnership Projects

Cedar Street Reconstruction in Beaufort

North Carolina provided information pertaining to four projects that demonstrate the DOT’s approach to partnerships. The first, Cedar Street in Beaufort, involved a roadway devolution in which the former state highway was reconstructed in a “road diet” configuration. U.S. Highway 70 historically passed through downtown Beaufort on Cedar Street. A new highway bypassing the city was constructed with its own stormwater system, but the old highway through downtown Beaufort was not included in this work.

The North Carolina Coastal Federation brought the potential project to the attention of NCDOT, then a partnership was struck between NCDOT, the North Carolina Coastal Federation, the North Carolina Division of Water Resources, and the town of Beaufort to construct the project. The DOT and the town of Beaufort reached an agreement whereby the old highway would be reconstructed and improved for its new use as a town street. The Cedar Street project required the state to repair the failing storm drainage system in the street, and the city to repair the old water and sanitary sewer system. From a traffic perspective, the project provided traffic calming through 14 “bump outs” that contained bio-retention cells, improved sidewalks and access control, and permeable pavement to allow stormwater to infiltrate the ground.

NCDOT funded the design and construction of the 14 bio-retention cells, funded the permeable pavement design, and constructed the underdrain tie-ins. The town and the Coastal Federation were awarded a grant to construct the permeable pavement. As part of the right-of-way transfer from NCDOT to the town, NCDOT made some structural drainage improvements and resurfaced Cedar Street. Beaufort also repaired and replaced waterlines and the sanitary sewer in the street and provided support by assisting with encroachment permissions from landowners. The town also fielded citizen questions and provided as-builts for the water and sewer lines along the project corridor.

The partnership was initiated just before the COVID pandemic in 2019, stopped during the pandemic, and restarted in early 2022. Construction was completed in late 2023. NCDOT received all the retrofit credit from the project, as the town’s MS4 permit has no retrofit provisions. Figure 4.1 shows the before and after condition of the project.

Cape Carteret Wetland Restoration

The second project of note in North Carolina is the restoration of a fresh and saltwater wetland destroyed by Hurricane Florence. The Cape Carteret wetland restoration project is notable in that it includes a partnership with two churches. NCDOT received retrofit credit for its TS4 permit as a result of the project because the wetlands receive runoff from an NCDOT roadway.

The wetlands were originally a set of two ponds owned by two different churches. In 2016, the ponds were drained and converted to wetlands to treat urban runoff from the churches, a nearby shopping center, and state highway NC-24. A large berm was constructed between the two wetlands. Stormwater runoff flowed through the freshwater wetland and then through a culvert under the berm into the lower saltwater estuary wetland. In September 2018, Hurricane Florence obliterated the berm separating the two wetlands and destroyed their function, particularly the saltwater wetland downstream.

The North Carolina Coastal Federation held the wetlands in a conservation easement, and they initiated partnership conversations with NCDOT. In partnership with the two churches, the Coastal Federation, and the town of Cape Carteret, NCDOT restored the wetlands to function as they were designed. The Coastal Federation funded the design, and the churches and the Coastal Federation granted the easements necessary for the construction and maintenance of the wetlands. NCDOT supervised the design, funded the construction, and performed the construction

administration. The project took three years from concept to completion. Figure 4.2 shows the before and after condition of the project site.

Smyrna Middle School Bio-Retention Pond

The third project also includes an unusual stormwater partner—an elementary school. Smyrna, North Carolina, is an unincorporated community historically dependent upon fishing and oyster harvesting, industries that depend upon clean water. An enthusiastic teacher at Smyrna Middle School spearheaded a partnership in 2008 to construct an infiltration basin on the school property along with educational signage. The initial device failed and was retrofitted as a bio-retention basin with an underdrain in 2009. NCDOT provided funding and technical expertise for the construction of the facility. The facility does not treat highway runoff but aside from its educational component, it helps to address a fecal coliform TMDL in the Jarrett Bay watershed, providing NCDOT a retrofit credit for their TS4 permit. Many students at the school are children of fishers and oyster harvesters, so they enjoyed the chance to work on a project with a direct connection to their families’ livelihood and learn about stormwater quality. Figure 4.3 shows the completed project.

North Carolina Zoological Park Constructed Wetland

The final NCDOT project is a partnership with the North Carolina Zoological Park and the NC Department of the Environment to construct a wetland on zoo grounds. The North Carolina Zoo welcomed more than 1 million visitors in 2022, so this partnership provided a high-visibility environmental education opportunity, as well as a site to treat runoff from a state highway and a large parking lot.

This project involved the construction of a wetland to treat stormwater runoff from a 20-acre drainage area that includes 11.1 acres of impervious parking lot serving the zoo’s northern entrance. NCDOT’s role in the partnership included the preparation of a feasibility study and construction drawings. The zoo used the feasibility study to apply for a $400,000 grant to fund construction of the stormwater wetland. The zoo owns and maintains the facility, while NCDOT provides water quality monitoring in accordance with the grant. NCDOT has received retrofit

credit for the project in accordance with their TS4 permit. Figure 4.4 shows a view of the educational signage and the constructed wetland.

4.2.2 North Carolina Summary

The main drivers for the North Carolina DOT’s retrofit program are state statutes and regulations that require the DOT to address nutrient load reductions, as well as the TS4 permit requirement that they complete 70 retrofit project credits over the 5-year term of the permit. NCDOT’s retrofit program has been included since their first TS4 permit in 1998 and has resulted in more than 300 retrofit projects throughout the state. The techniques generally used for these retrofit projects are retention facilities, flow-through facilities, detention facilities, proprietary stormwater treatment, permeable pavements, and constructed wetlands.

When establishing third-party partnerships, NCDOT typically takes a lead role because they have the bulk of the funding, design, technical expertise, and construction administration

capacity. NCDOT has a long and successful relationship with the North Carolina Coastal Commission and partners with them on many projects. The majority of NCDOT third-party partnerships are located in urban areas and include municipalities, other state agencies, private non-profit organizations, and schools or universities.

NCDOT has no comprehensive written guide to third-party partnerships or standard memorandum of understanding. Most of the agreements are reported to be commitments in meetings, discussions, and e-mails, and the agreements are finalized in letters and memorandums. NCDOT does see the need for a more formal standardized approach.

The biggest lesson NCDOT has learned is that regional partner projects provide the highest benefit, both performance and societal, but they are far more challenging to administer. With 70 retrofit project credits required over 5 years, some of the projects have to be simple and inexpensive to design and execute. Yet, partnerships are rarely simple or inexpensive. With multiple partners come multiple opinions, and often the partners are more concerned with aesthetics while the DOT is more concerned with function.

4.3 California

California’s Department of Transportation, commonly referred to as Caltrans, has a unique approach to permanent stormwater facility partnerships in that nearly all are TMDL related. Caltrans is required to implement stormwater pollutant control measures to address its contribution to the stormwater quality impairment of the receiving water. Cooperative agreements are explicitly listed as a means to address these impairments.

In 2022, the California State Water Resources Control Board issued a statewide MS4 permit for Caltrans along with an accompanying time schedule order in which Caltrans is required to comply with a total of 88 TMDLs before December 31, 2034. Additionally, the MS4 permit requires that Caltrans implement a stormwater asset management plan and retrofit program that includes a prioritized list of projects that replace or upgrade facilities at risk of failure as well as facilities providing inadequate stormwater treatment because of either design or performance deficiencies. The retrofits from the list are to be completed at a rate of 2% per year starting the third year of the permit (2025) then 3% per year thereafter.

In California, each watershed is managed by the Water Resources Control Board, which is subdivided into multiple autonomous regional authorities. These regional authorities set load reductions for the various stakeholders in a particular watershed. Because of both their statewide MS4 permit and the accompanying TMDL time schedule order, Caltrans partners with other MS4 agencies throughout the state. Projects are designed regionally, with the autonomous regional water board authority assigning load reductions to the various MS4s.

In some rural areas on the north coast, where Caltrans is the only MS4 agency, the TMDL reductions are not tied to DOT operations. Instead, “legacy loadings” are recognized and BMPs constructed by the DOT because there are no other MS4s. The autonomous regional authority assigns loads to Caltrans and approves projects that will allow Caltrans to meet their TMDL responsibilities through offsite projects. Examples of such projects are treating sediment from unpaved logging roads or stream stabilization projects funded by Caltrans but not connected to DOT sediment production. Partners on these rural north coast projects include California State Parks and the Bureau of Land Management. Recently, California regulations changed, and Caltrans can now partner with non-governmental organizations on rural stormwater projects. In most instances, the partner identifies the project and prepares the plans, then Caltrans funds the construction and gets the regulatory credit.

Caltrans generally partners by contributing cash and technical support to regional permanent stormwater facility efforts. Occasionally, Caltrans will participate in partnerships with

construction efforts, but seldom will they provide operation and maintenance. Because Caltrans right-of-way is generally only 2% to 4% of a given watershed, the agency is typically a contributing partner, rather than a lead partner, in regional facilities.

Both the Caltrans MS4 permit and the associated time schedule order encourage partnerships between the agency and local municipalities to provide shared permanent stormwater facilities that will address impaired watersheds for which Caltrans holds some responsibility. Caltrans receives waste load reduction credit, trash credit, or both for financial contributions to these regional partnerships.

Caltrans has two programs for external partners to apply for funding from the DOT. The first is a cooperative implementation agreement (CIA). All phases of stormwater treatment facility project development can be funded through CIAs. These phases include planning, environmental studies, design, right-of-way acquisition, and construction. The external partner typically owns, operates, and maintains the facility. Caltrans provides funding for the design and construction, and the duties of each partner are documented in a memorandum of agreement. The project must include treatment of runoff from Caltrans right-of-way. The proposed project must gain approval of the regional water board before the partnership is executed. This state-funded program lacks a permanent funding source, so the amount of funds available is unpredictable year to year.

The second external funding mechanism is financial contribution only (FCO). Only capital construction efforts for stormwater treatment facilities are eligible to be funded through FCOs. Treatment of runoff from Caltrans right-of-way must be included. The external partner typically owns, operates, and maintains the facility. Caltrans provides funding only for the construction. This is documented in a memorandum agreement. The FCO program runs on a 2-year cycle. On May 1 of even-numbered years, basic project details are submitted to reserve funds. By March 1 of the following odd-numbered year, additional details of the project are submitted.

FCO projects are sorted by priority, and projects that advance to construction are funded within two years. All planning, design, environmental clearance, permitting, right-of-way, and construction administration are the responsibility of the local municipality. FCO projects that do not rise to the top of the priority list remain eligible for funding in following years. Historically, the FCO program was 89% federally funded with an 11% state match. However, in some cases the partners are reluctant to participate with the constraints of federal aid funding, so in those instances, the grants can be completely state funded. Generally, construction funding in the FCO program is the easiest to obtain within the Caltrans partnership program. The CIA program, which funds the broader planning and operational elements of projects, is more challenging, as there is no dedicated funding source every year.

Aside from the CIA and FCO programs, whereby external partners propose partnerships, Caltrans is able to initiate partnerships. The partnerships described earlier in rural northern California, where Caltrans treats runoff from outside their right-of-way, would not be possible under the CIA or FCO programs. The need for TMDL reductions drives these rural partnerships, as treatment of the legacy loadings is the most effective way to reach the targets.

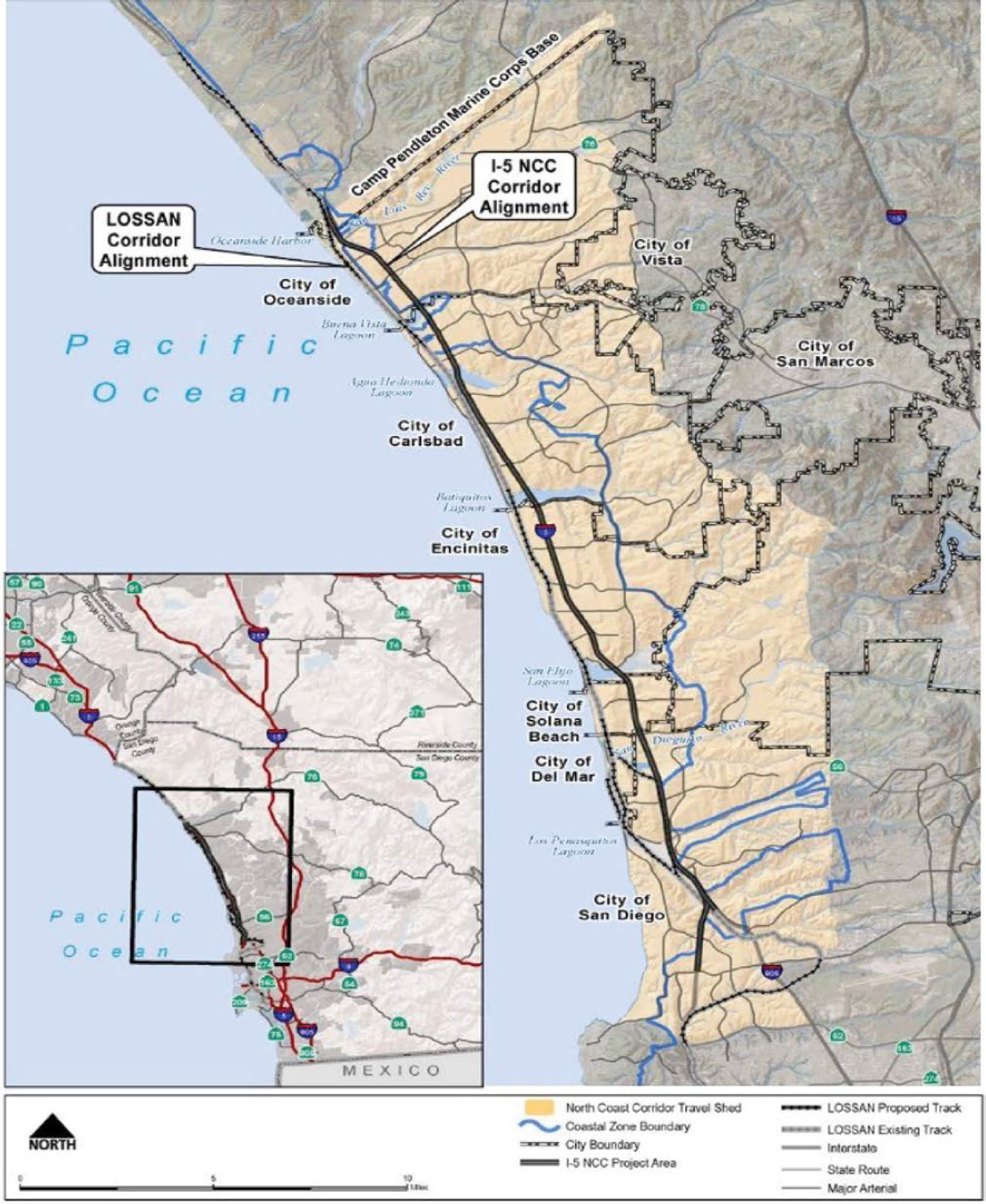

4.3.1 California Signature Partnership Project: I-5 Stormwater Control

I-5 crosses multiple watersheds as they flow to the Pacific Ocean (Figure 4.5). Figure 4.6 shows the post-construction condition of I-5 at Lomas Santa Fe biofiltration swales in Solana Beach, CA. A series of tables in Appendix E of the I-5 North Coast Corridor Public Works Plan/Transportation and Resource Enhancement Program (NCC PWP/TREP) document provides details of five major watersheds in the corridor. Table 4.1 summarizes all the details for the Peñasquitos watershed included in Appendix E of the NCC PWP/TREP document.

The NCC PWP/TREP is a long-range planning document intended to govern the development of the interstate over four decades. The information included in the water quality appendix

Table 4.1. Summary of Peñasquitos Watershed parameters (compiled from Caltrans 2016).

| Area of watershed | 25,924 acres |

|---|---|

| Area of I-5 right-of-way | 288 acres |

| Interstate right-of-way (percentage of total watershed) | 1.10% |

| Pollutants in Los Peñasquitos Creek | Total dissolved solids Selenium Total nitrogen Fecal coliform Enterococcus |

| Caltrans-targeted design constituents | Sediment Nitrogen |

| Existing impervious area of interstate | 193.5 acres |

| Existing impervious area currently treated | 7.7 acres |

| Additional proposed impervious area | 30.0 acres |

| Proposed impervious area treatment | 41.7 acres |

| Amount of proposed retrofit treatment | 4.0 acres |

establishes a framework for all permanent stormwater facility projects necessary for the highway, the relative magnitude of the highway’s impact on the various watersheds, and the highway’s share of various pollutant loads. Such a document provides a starting point for identifying potential partnerships with the multiple jurisdictions that also affect the impacted watersheds. Further, the water quality appendix documents the stormwater treatment of an existing facility and how stormwater treatment will be provided with the expansion of the transportation facility. It also identifies how many of the proposed permanent stormwater facilities will be retrofit facilities and what sorts of facilities Caltrans envisions for each watershed. The local agencies can use the water quality appendix document to initiate partnership projects in those same watersheds through either the FCO or CIA Caltrans permanent stormwater facility funding programs.

4.3.2 California Summary

The main drivers for retrofit projects at Caltrans are meeting the TMDL timeline goals outlined in the MS4 permit and working with the autonomous regional authorities of the state water

board. The retrofit practices include retention and detention facilities, flow-through facilities, and proprietary stormwater treatment. The retrofitting occurs throughout the state and is tied to TMDL responsibilities. Caltrans does not have written guidance for their partnership program but acknowledges that it would be a good addition. Caltrans does have a comprehensive stormwater maintenance manual (Caltrans 2018).

Caltrans partners with a variety of third-party partners, including municipalities, counties, special districts, other state agencies, and private non-profits. The partnerships exist throughout the state in high-priority watersheds. Many of the third-party partners are MS4s and bring funding streams to the project. Some of the third-party partners, particularly in the rural north coast where Caltrans is the only MS4, contribute design and right-of-way to the project while Caltrans funds the construction.

The most important lesson that Caltrans has gained from their partnership experience is that frequent communication and maintaining an open mind are critical. This helps to defuse mistrust that can occur with local partners. An important contribution that the DOT can provide is helping the local agency overcome the bureaucratic red tape involved in permanent stormwater facility permitting. It is important to be collaborative with all partners’ goals and try to make these goals common ones. Finally, whenever solutions are agreed upon by the partners, it is critical to have those decisions approved by the regulator. A challenge that Caltrans has faced with the TMDL focus of their partnership program is that it can be difficult to quantify load reductions at the project-scoping stage. As the project advances, it is difficult to change various stakeholders’ load reductions once commitments have been made.

4.4 Rhode Island

Rhode Island has a broad partnership and retrofit program rooted in a 2015 consent decree from the EPA. The Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) has a Phase 2 MS4 permit from 2003. In this permit, RIDOT was required to prepare a TMDL implementation plan only for waterbodies with EPA-approved TMDL reports. In 2009, RIDOT was audited and found non-compliant in illicit discharge detection and elimination, maintenance discharges, and impaired waters, resulting in the 2015 consent decree. As part of this consent decree, a Stormwater Control Plan was mandated, which required an implementation plan for both the TMDL-listed waterbodies and waterbodies with a stormwater impairment. These affected watersheds cover two-thirds of the state, with considerable retrofit responsibilities. The consent decree does not require partnerships, but RIDOT has found them necessary to satisfy the terms of the consent decree.

In the ensuing years, RIDOT completed the watershed plans and has to date constructed about two dozen projects. The consent decree placed a 25% cap on partnership projects, rather than onsite treatment. This cap was implemented to prevent the DOT from taking only the “low-hanging fruit.” However, at this stage of the program, the regulator has generally granted permission to exceed that 25% cap. As in other states, Rhode Island’s preference is to fund projects by paying partners cash in lieu of participation, but the DOT will and has participated in any type of partnership. The funding RIDOT uses for the stormwater control program is generally state money, and it provides good “seed” money for federal grants that require some percentage of state or local matching funds.

Though Rhode Island has a massive amount of ocean coastline relative to its size, the bulk of the waters on the impaired or TMDL list are freshwater, so freshwater is the focus of Rhode Island’s program. The bulk of the stormwater treatment units (Rhode Island’s name for SCMs or BMPs) are designed for nutrient removal. With impaired waters, the goal is a 10% impervious equivalent in treatment. This means that a site or watershed urbanized to a high level of imperviousness, perhaps 70% or 80%, would install facilities that would capture that excess runoff and mimic natural processes to reduce the runoff to what would occur with only 10% imperviousness.

In current Rhode Island stormwater partnerships, RIDOT is a contributing partner, with the partner agencies acting in the lead role and initiating the partnership. RIDOT has participated in partnerships in which they simply fund the infrastructure, as well as in partnerships with shared construction and maintenance responsibilities. Like other state DOTs, RIDOT’s preference is to fund the facility and let others construct and maintain it. This preference is rooted in the fact that highway right-of-way is only a small fraction of the typical watershed.

RIDOT partnerships tend to focus on three groups:

- The Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council (WRWC), a council chartered under the larger Rhode Island Rivers Council umbrella. The Rhode Island legislature created the Rhode Island Rivers Council to improve and preserve the state’s waterbodies with the hope that the improved water quality would lead to increased river use.

- The Rhode Island State Conservation Committee, an agency within the state’s Department of Environmental Management.

- The Audubon Society, an environmental advocacy organization.

4.4.1 Rhode Island Signature Partnership Projects

Olneyville Square

Rhode Island identified two projects that demonstrate the effectiveness of their partnership program. The first is the Olneyville Square project, for which RIDOT partnered with Citizens Bank and the WRWC to improve a traffic square and associated private parking lot. The project included pavement removal, swales, and bio-retention as well as improved pedestrian access, linking the square to the larger Woonasquatucket River Greenway. Previously, the area drained untreated directly into the Woonasquatucket River. The partnership was unusual in that it included a private business, not just governmental agencies. Figure 4.7 shows the before and after condition of the project.

Stormwater Innovation Center at Roger Williams Park

The second project of note is the Stormwater Innovation Center at Roger Williams Park in Providence. This facility is an outdoor classroom constructed by a broad partnership including RIDOT, the City of Providence, the Audubon Society, the Nature Conservancy, the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Institute, the Restore America’s Estuaries Southeast New England Program, and the University of New Hampshire Stormwater Center.

Roger Williams Park was first constructed in 1878, and the ponds in the park were severely degraded from urban runoff. The ponds regularly exhibited cyanobacteria blooms that resulted in them being listed as impaired in 1992. As a result of a consent agreement between the City of Providence and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, more than 40 nature-based stormwater practices were installed in the park between 2017 and 2020. The results were impressive, so the partners assembled to create a facility to provide training, testing, and public education on the function of nature-based stormwater practices. The City of Providence provides the site while RIDOT, and other partners provide funding and in-kind contributions. In 2023, the center’s budget was $431,000, with $150,000 coming from RIDOT, $198,000 from Restore America’s Estuaries, $70,000 from the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program, and $19,000 from the Restore America’s Estuaries Southeast New England Program network. In-kind contributions include technical services from the University of New Hampshire and parks staff from the City of Providence. RIDOT receives regulatory compliance credit within their MS4 permit as a result of their participation.

The Stormwater Innovation Center includes multiple elements of green infrastructure that actively improve stormwater quality. It also contains an educational component that describes the impact of urban non-point sources of pollution and demonstrates techniques available to treat these pollution sources. These facilities are used as a hands-on laboratory to study various types of stormwater technologies. Staff from cities, towns, contracting and consulting engineering companies, and academic institutions can use the facility to construct and experiment with prototypes. Figure 4.8 shows the signature pond at the facility.

There are currently 34 stormwater infrastructure practices demonstrated within the Stormwater Innovation Center, both structural and non-structural. These include infiltration basins, sand filters, bio-retention rain gardens, bio-swales, pavement removal projects, and buffer plantings. It is expected that these features will evolve as stormwater technologies change. Water quality and quantity are monitored throughout the center to evaluate how the various techniques perform under different weather conditions and to understand how they might be improved.

Table 4.2. Rhode Island’s typical stormwater partnership structure.

| Partner | Role |

|---|---|

| RIDOT Environmental Division | Oversight |

| Partnership agency, generally a non-profit (WRWC, Rhode Island State Conservation Committee, Save the Bay) | Proposes projects, develops charter with RIDOT Environmental, and oversees the design and construction and payments |

| RIDOT stormwater consultant | Design engineer paid directly by RIDOT |

| Partner generally a Rhode Island city/town, school department, or nonprofit (church, social club, park, homeowner) | Landowner partnerships exclusively use non-state right-of-way, so the partner owns the right-of-way and is responsible for operation and maintenance but provides easement for RIDOT inspection |

| Financial partner (sometimes) | Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank may work with partner to fund some or all of the construction, depending on agreement |

| RIDOT | Periodic inspection |

4.4.2 Rhode Island Summary

The primary driver for stormwater retrofits for the Rhode Island DOT is the consent decree that transformed their MS4 permit and program in 2015. The stormwater retrofit practices RIDOT uses are flow-through facilities, proprietary stormwater treatment devices, and permeable pavements. The retrofit practices are conducted throughout the state, involve both onsite and offsite flows, and are targeted at high-priority watersheds to meet the requirements of the consent decree. Similarly, the third-party partnership projects are distributed throughout the state and consist of municipalities, special districts, and private non-profits. Partnerships are often triggered through RIDOT’s Stormwater Control Plan process, which identifies potential partnerships with municipalities or non-profits. Potential projects are also identified through community outreach and partnering organizations’ knowledge of RIDOT’s needs and abilities. Generally, all partnerships in this program are structured the same way. The typical structure is shown in Table 4.2.

Rhode Island has had many positive results from their partnership programs. The projects built through the program are found to be cheaper, faster, and more effective than permanent stormwater facilities focused solely on onsite highway runoff. Another benefit to partnership with RIDOT is that the DOT is able to underwrite loans from the state-funded Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank to get projects under way, as well as to provide matching funds for federal grants to assist partners that have limited funding. The financial structure of the partnerships varies depending on whether grant funding is involved. Sometimes RIDOT will pay 100% of the project from conception to as-built, and the partner agrees to maintain it. Other times, RIDOT will provide the financial match to a partner’s grant-funded project.

From conception to construction, stormwater partnership projects typically take several years. However, as the program is maturing and becoming well established, partnership projects are taking less time and RIDOT can generally take advantage when opportunities arise. There is also considerable community improvement and an educational element to these projects. A stream improvement project can create green space amenities that can be enjoyed by the community, whereas an underground vault is hidden from the public and few understand its function. RIDOT provided several example agreements for their partnership projects, which are included in Appendix E.

4.5 Summary

Of the four states that participated in the case examples, two of them, California and Rhode Island, have based their partnership and retrofit programs largely upon the need to satisfy TMDL or other impaired water requirements. In Rhode Island’s case, the impairment issue was linked to

their MS4 permit through a consent decree that settled a permit non-compliance finding from a 2009 audit. North Carolina has a retrofit program within their TS4 permit and while it considers TMDL issues, it is also based on a state statute and regulation that requires that they address nutrient pollution. Florida has no retrofit requirement in their MS4 permit but participates in partnership projects to meet state regulations and cooperate with other agencies and regional watershed districts.

Rhode Island’s partnership program is well structured, with each partnership having similar properties. California participates in a large number of partnerships but does not have written guidance to structure their formation. Florida is implementing the WATERSS program that seeks to identify partnership opportunities in a systematic way, but the actual agreement processes are not as well documented. North Carolina also does not have a systematic process for partnership formation or documentation but relies on conversations, e-mails, and memorandums to document the elements of the partnership. Both North Carolina and California would welcome a more rigorous guide to managing partnerships.

All four case example DOTs believe partnerships are a positive benefit to their stormwater control programs, sharing the belief that the effectiveness and the economies of the third-party partnership projects outweigh their logistical inconvenience. All four agree that the preferable way for state DOTs to partner is through a financial contribution to another agency that is then responsible for construction, operation, and maintenance. Rhode Island runs all its current partnerships that way, and California follows this approach for the majority of its partnerships. Florida and North Carolina participate more actively on certain partnerships than do Rhode Island and California.