Open-Book Pricing Practices for Construction Manager/General Contractor and Progressive Design-Build Projects (2025)

Chapter: 4 Case Examples

CHAPTER 4

Case Examples

This chapter will provide the details of nine case examples of projects for which open-book negotiating procedures were employed. The case examples were selected to provide a cross section of CM/GC and PDB projects across the United States. The primary factor in case selection was the availability of participants in the project’s open-book negotiation. The second consideration was whether the contractor and agency perceived the negotiation to be successful. Success was not defined as mutual agreement on the GMP but rather on whether the parties believed the facts presented in the negotiation were trustworthy. The case examples are as follows:

- Lafayette Bascule Bridge (LBB) CM/GC Project Bay City, MI

- Cromwell Marine Creek Road (CMCR) Widening Improvements Construction Manager-at-Risk (CMAR) Project, Fort Worth, TX

- Twin Ports Interchange (TPI) CM/GC Project, Duluth, MN

- Sellwood Bridge Replacement CM/GC Project, Multnomah County, OR

- I-95 and SR 896 Interchange CM/GC Project, Newark, DE

- Scofield Avenue Undercrossing Seismic Retrofit (SSR) CM/GC Project, Richmond, CA

- Bangerter 4700 S Interchange PDB Project, Salt Lake City, UT

- I-270 Innovative Congestion Management (ICM) PDB Project, Montgomery and Frederick Counties, MD

- Boeckman Dip Bridge and Road (BDBR) PDB Project, Wilsonville, OR

Case example interviews were conducted via Zoom video conference during the spring of 2024. Drafts of the case example summaries were reviewed and approved by participating state DOTs to ensure the information presented is factual and correct.

4.1 LBB CM/GC Project Bay City, MI

Agency: Michigan DOT

Type of Project: Full replacement of existing bridge

Delivery Method: CM/GC was selected due to the complexity of the project because this is nonstandard bridge work. Michigan DOT wanted input on foundations, barge versus trestle access, and staging areas.

Initial Budget Value: $40–45 million in 2018 dollars.

Final Negotiated Value: Not awarded. Off-ramp executed.

Scope: The new bascule bridge will be 513′ long with a 190′ double leaf rolling bascule center span. The bascule span cross section includes steel girders, floor beams, and stringers. The floor system is composite with the exodermic grid deck. The bridge has an underdeck counterweight, and its structure is supported by large, reinforced concrete piers. Figure 24 is a picture of the existing bridge.

4.1.1 LBB Goals

The primary goal was to replace an aging bridge that had to be closed about 10–20 times a year for maintenance. The existing substructure, built on timber piles, was rated scour critical. In preparation for the closure of the bridge, $2.7 million was expended to repair the M-25 Veterans Memorial Bridge, and improvements were made to state and local streets to prepare the detour routes for increased traffic during the 2.5-year vehicle detour period.

4.1.2 LBB Challenges

This is a nonstandard bridge type and requires a specialized construction approach to facilitate the design in a manner that will provide a constructable project. The technical challenges of this project include:

- Contaminated soils,

- Limited staging areas,

- Removal of existing bridge and timber foundation piling,

- Potential for flooding,

- Winter construction,

- Long procurement durations, and

- A 2-year vehicle detour duration limit.

4.1.3 Details of the Open-Book Process for LBB

Table 5 lists the negotiated elements of the GMP. The details of the other open-book–related cost factors are detailed in subsequent paragraphs.

Preconstruction Fee: The preconstruction fee was specified by MDOT in the solicitation.

Construction Services Fee: This fee was negotiated. The contractor provided an audited general and administrative (G&A) rate, which was added to a profit percentage and used as the basis of the fee.

Cost Model: The cost model was developed by the contractor on this project. Standard Michigan DOT pay items were used as the basis for 70–80% of the cost model, and unique items were created in situations where standard pay items were not adequate to compare the cost for certain scope elements, such as establishing and restoring staging areas.

Table 5. LBB negotiated elements of the GMP.

| Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design fee | Profit | x | Sequence of work | x | |

| Preconstruction fee | Allowances | x | Risk | x | |

| Construction services fee | x | Equipment rates | x | Contingencies | x |

| Home office overhead | x | Quantities of work | x | Contract terms | |

| Project indirect costs | x | Production rates | x | Schedule | x |

| General conditions | x | Subcontractor work | x |

Risk: Risks were identified, and cost and schedule impacts were discussed; however, risk impacts and allocation were not finalized prior to exercising the off-ramp.

ICE Involvement: Yes, ICE was engaged. The ICE’s primary responsibilities were reconciling quantities to align on the project scope. The ICE developed a contractor-style cost estimate, which was used in comparison with the contractor’s estimate.

Open-Book Negotiations Result: The contractor’s, ICE’s, and engineer’s estimates ranged from $70 million to $90 million. The off-ramp was exercised, and the project was deferred in 2020 because the prices were well over the amount of available funding.

Off-Ramp: Yes.

4.1.4 Interviewees Comments

If the project was procured as a DBB project, it would not have been awarded so high over the budget. MDOT found the contractor’s input on the design plans to be very helpful. MDOT continues to use the CM/GC process in other projects, even though this project exercised the off-ramp. At the time of this project, the CM/GC contractor had recently gained experience constructing movable bridges. The cost increase was due to existing timber piles that will need to be removed in deep water, steel prices (the project includes more than 7 million pounds of steel), increased foundation size (which was determined to be a necessity to avoid future scour concerns), and increased labor rates.

MDOT has awarded the project as a DBB delivery. The agency has the benefit of early contractor involvement and the ability to access current material costs for steel and other commodities.

4.1.5 Key Takeaways

The open-book process provided MDOT with real-time transparent pricing that allowed it to make an informed decision to execute the off-ramp. The interviewees did not suspect the CM/GC contractor of inflating the GMP because Michigan DOT had access to the current market prices at the time and the benefit of an experienced, movable bridge contractor’s input on the design.

The initial estimate was low because the scope of the final project was different than the actual scope of work. The addition of pile removal and the increase in foundation size to account for scour are two examples of added scope. The open-book process in CM/GC permits early contractor involvement in identifying scope gaps, and the transparent pricing allows the DOT to have confidence that the early budget estimates were indeed incomplete and did not reflect current market conditions. Thus, a decision to delay the project and seek additional funding is justified.

4.2 CMCR Widening and Improvements CMAR Project, Fort Worth, TX

Agency: City of Fort Worth (CFW), Texas

Type of Project: Roadway widening and bridge

Delivery Method: CMAR was selected because the CFW needed an expedited schedule. Also had a desire to add CMAR to its procurement system for use in three future projects.

Initial Budget Value: $24.1 million

Final Negotiated Value: $44.9 million

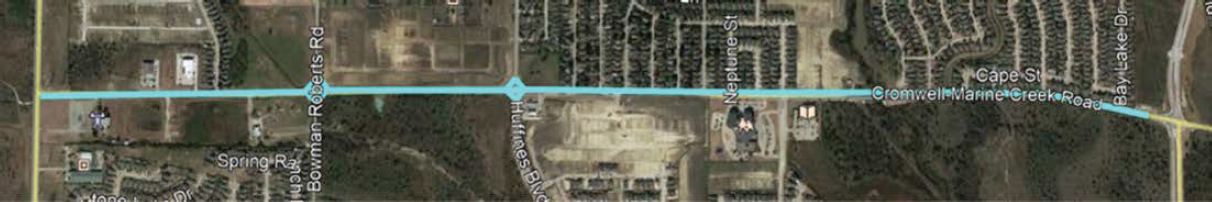

Scope: The project consists of the reconstruction of 2.11 mi of CMCR from Boat Club Road to Marine Creek Parkway. The Cromwell Road corridor provides access to Texas NW Loop 820. Figure 25 is a plan view of the project alignment.

The project includes 6′–10′ sidewalks and shared used paths, streetlights, 20″ ductile iron water line relocation, and a 4-lane divided (4–11′) commercial and neighborhood connector road with the ability to reduce the median and widen to 6-lane in the future. The project includes conversion to curbed road with an enclosed drainage system with inlets and upsized culverts, modification of an existing traffic signal at Boat Club Road and Huffines Boulevard, and a new traffic signal at Bowman Roberts Road and Crystal Lake Drive. A 201′ span concrete bridge over Marine Creek on the east side of the project and modifications to the existing roundabout at Marine Creek Parkway are also components of the project scope. It required coordination with TxDOT, which operated and maintained Marine Creek Parkway (NW Loop 820).

4.2.1 CMCR Goals

The primary goal was to expedite the delivery of the project and minimize disruption to traffic because the route was expanded from two to four lanes of traffic to increase the capacity of this major arterial route. Additionally, the existing culvert on Marine Creek was replaced with a bridge to alleviate flooding issues. CFW also had a long-term goal of increasing the use of CMAR as a means to accelerate the delivery of its roadway program. CMCR was the first project and acted as a pilot for future projects.

4.2.2 CMCR Challenges

The budget for CMCR was established before the COVID-19 pandemic and was based on a scope of work that was purely conceptual. The CFW was not prepared to see the current post-pandemic escalation of construction prices. Additionally, the final scope of work was significantly increased from the scope used for the budget. Hence, the open-book negotiation process, though difficult, was the key to agreeing upon a GMP that the CFW believed was reasonable.

4.2.3 Details of the Open-Book Process for CMCR

Table 6 lists the negotiated elements of the GMP.

Preconstruction Fee: The preconstruction fee was established in the contractor’s proposal.

Construction Services Fee: This fee was also established in the contractor’s proposal along with a profit percentage, which was proposed to be 5.5%. It was carried into the contract and applied without negotiation.

Cost Model: The cost model was developed by the contractor for this project. The CM/GC contractor provided the model at 60% design completion.

Risk: A jointly developed risk matrix was developed and used to guide negotiations. Contingencies were included in the GMP work packages.

ICE Involvement: Yes. The ICE’s primary responsibilities were to validate the cost model, participate in scheduled discussions, and furnish a third OPCC at the final GMP establishment. The ICE came to the project at the 60% design milestone. It based much of its analysis on the documents, which created the following issue: The ICE’s schedule did not include the final scope of work. The contractor had to provide its schedule to the ICE, and the ICE participated in the negotiation of the final schedule.

Open-Book Negotiations Result: A mutually agreed-upon construction price was achieved. The contractor’s GMP and the ICE’s estimate were in roughly the same range. The final agreed-upon GMP was used to request additional funding to complete the project.

Off-Ramp: No. The open-book negotiation process gave the CFW confidence in the integrity of the contractor’s proposed GMP. Using the ICE enabled the owner to tell its City Council that the construction cost was fair and reasonable.

4.2.4 Interviewees Comments

CFW interviewees expressed the sentiment that negotiations were “lopsided,” with the contractor bringing a much greater understanding of the project’s cost than the owner. Limited staff prevented the CFW from developing an internal estimating unit, making it dependent on its design consultants to provide estimating services. The open-book negotiation process emphasized the need for the owner to put more focus on general conditions and scheduling. Ultimately, a joint value engineering session was held to further assess the scope of work and identify potential savings. This assessment resulted in a reduction of $475,000.

The project began as a DBB delivery but was changed to CMAR. As a result, the contractor was retained at a point in the design development when it was too late to propose alternative technical concepts that might have mitigated the impact of the escalation. The definition of “substantial completion” was broken out in negotiations, and the added level of detail permitted

Table 6. CMCR negotiated elements of the GMP.

| Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design fee | Profit | Sequence of work | x | ||

| Preconstruction fee | Allowances | Risk | x | ||

| Construction services fee | Equipment rates | Contingencies | |||

| Home office overhead | Quantities of work | Contract terms | |||

| Project indirect costs | Production rates | Schedule | x | ||

| General conditions | x | Subcontractor work | x |

a reduction in general conditions costs. The project was divided into design and construction packages, which permitted the contractor to bid out the subcontractor packages and replace plug numbers with actual subcontractor quotes. The content of the subcontractor bid packages was negotiated, and the CFW approved key subcontractors to be selected on a best-value rather than a low-bid basis.

4.2.5 Key Takeaways

The off-ramp not being exercised after an initial 100% increase in price shows the value of the open-book negotiation process for the CMCR project. Additionally, the CFW’s current delivery of its fifth CMAR project testifies to the effectiveness of the process in providing the necessary transparency of pricing that permits the owner’s upper management to understand that the original budget estimate was in error and that the increase in cost was not due to the CMAR contractor attempting to gouge the agency. Finally, while the ICE was not retained until the final GMP negotiations commenced, it provided evidence that the CFW staff had indeed endeavored to determine whether the CMAR’s proposed GMP was fair and reasonable.

4.3 TPI CM/GC Project, Duluth, MN

Agency: MnDOT

Type of Project: Roadway and Bridge

Delivery Method: CM/GC was selected because the Duluth District wanted to control the design, complex staging requirements, and complex technical requirements.

Initial Budget Value: $200 million

Final Negotiated Value: $275 million for Phase 1 + $158 million for Phase 2

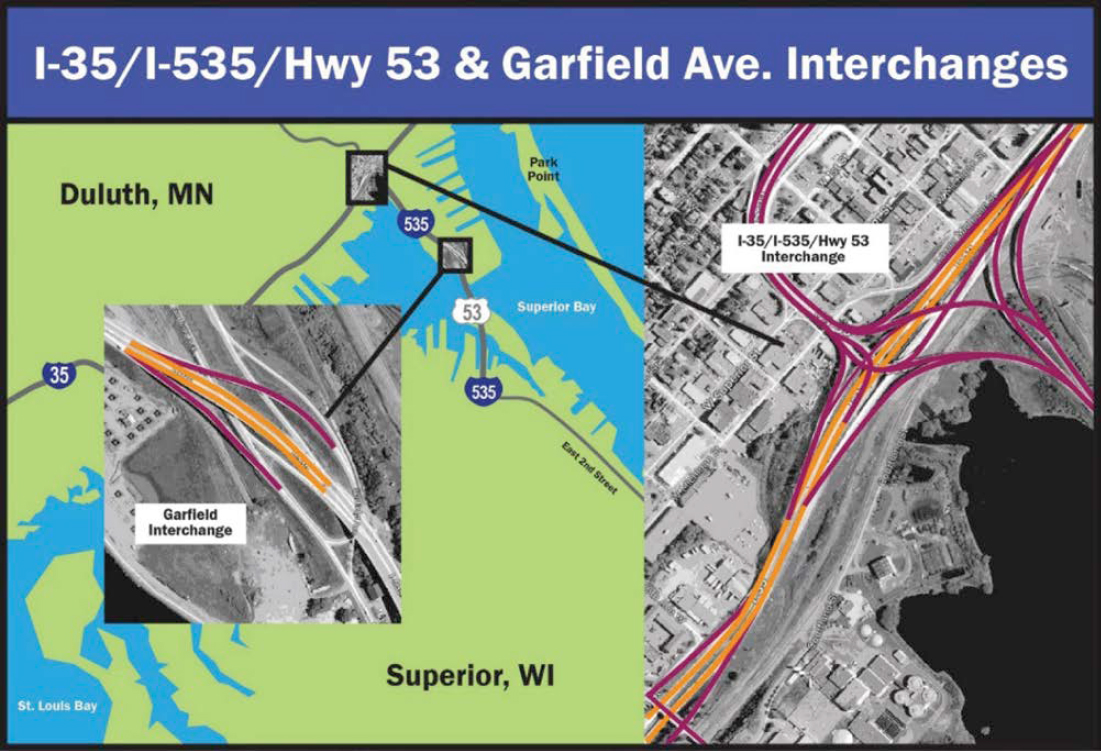

Scope: This project was developed to better accommodate freight movements to and from the Port of Duluth-Superior Clure Terminal, which generates 2,500 to 4,000 oversize/overweight loads per year that must be routed around the two interchanges on 1-35 and 1-535 on local streets because of load restrictions. The interchanges serve 3,450 heavy commercial trucks per day. MnDOT applied for a Fostering Advancements in Shipping and Transportation for the Long-Term Achievement of National Efficiencies (FASTLANE) grant to partially fund the project with the remaining monies coming from the MnDOT, the City of Duluth, and other grants. Figure 26 is a depiction of the TPI project footprint.

“Major components of the original scope include:

- Reconstruct the I-35/I-535/Highway 53 interchange

- Replace 3 bridges in the I-535/Garfield Avenue interchange

- Improve safety of the I-35/I-535/Highway 53 interchange

- – Provide a new conventional design for improved safety and mobility

- – Provide all exits and entrances on the right

- – Improve merging sight distance and eliminate merge conflicts

- – Eliminate weaving problems near the interchange

- – Provide lane continuity for through I-35 traffic” (MnDOT 2023).

4.3.1 TPI Goals

The critical project success factor was maximizing the use of available funding outside the MnDOT state highway improvement fund. The FASTLANE grant was the major source of targeted external funding, and MnDOT sought additional grants from programs related to environmental improvement and community impacts, which required the involvement of other

third-party stakeholders at the state and local levels. It also required the consummation of an agreement with the railroad that services the port. Because of the project’s urban footprint, staging and work sequencing had to be planned in a manner that did not disrupt the commercial freight entering and leaving the port. Lastly, environmental restoration and remediation became a major goal as a condition for receiving National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) clearance.

4.3.2 TPI Challenges

The TPI project was an extremely complex project involving risks that were difficult to discern during the early stages of project development. The biggest influencing factor was the incremental growth of scope as the project matured. The project team committed to maintaining a high level of engagement and transparency throughout the project development process. Early project estimates were based on limited scope development due to the need to accelerate the project development process. For example, MnDOT received a $20 million Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD) grant in 2018, which would have expired in Fiscal Year 2020 if unused, which created a need to accelerate those aspects of the project covered by the BUILD grant.

Other challenges that affected the project cost and schedule were:

- Environmental context factors, including soil contamination, which required dewatering due to a high water table, stream mitigation, and water quality management;

- Third-party requirements, including railroad coordination and required service infrastructure improvements, utility removals, relocations and installations, local street network improvements and supportive traffic management to the Port of Duluth-Superior Clure Terminal and the Duluth Entertainment Convention Center; and

- Limited project space for staging, storage, and mitigating soil contamination, which resulted in a need to transport contaminated soils to an offsite area.

4.3.3 Details of the Open-Book Process for TPI

Table 7 lists the negotiated elements of the GMP. The details of the other open-book related cost factors are detailed in subsequent paragraphs.

Preconstruction Fee: The preconstruction fee was established using hourly rates negotiated with the contractor.

Construction Services Fee: This fee was established by a MnDOT-mandated fixed percentage of 12.5%, which was published in the solicitation.

Cost Model: The cost model was jointly developed on this project. The CM/GC contractor led the exercise; the engineer’s estimate consultant and the ICE reviewed and validated the final model.

Risk: Risk was not included in the base estimate. It was addressed separately outside the estimate and quantified and allocated later in the GMP development process.

ICE Involvement: Yes. The ICE’s primary responsibilities were to validate the cost model, participate in scope discussions, and furnish a third OPCC at each milestone.

Open-Book Negotiations Result: A mutually agreed-upon construction price was achieved. The contractor, ICE, and Engineers Estimate were within 2% of each other at a GMP amount that exceeded the available funding. The contractor and MnDOT with the ICE’s assistance reevaluated the project scope and developed a plan for phased construction to match available funding. The CM/GC contractor was retained for the Phase 2 construction contingent on availability of funds.

Off-Ramp: No. The open-book negotiation process gave MnDOT the confidence in the integrity of the contractor’s proposed GMP. When it was determined that the proposed costs exceeded available funding, MnDOT engaged the contractor and the ICE in the rescoping process and developing a Phase 1 scope of work that could be built for the available funds. The remainder of the work was included in Phase 2 and awarded to the CM/GC contractor when funding became available.

4.3.4 Interviewees Comments

Open-book negotiating procedures allowed MnDOT to make informed decisions and preserved the flexibility to change the procurement strategy when it became apparent that

Table 7. TPI negotiated elements of the GMP.

| Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design fee | Profit | Sequence of work | x | ||

| Preconstruction fee | x | Allowances | Risk | ||

| Construction services fee | Equipment rates | Contingencies | x | ||

| Home office overhead | Quantities of work | Contract terms | x | ||

| Project indirect costs | x | Production rates | Schedule | x | |

| General conditions | x | Subcontractor work |

the available funding was inadequate. The negotiation proceeded in a manner that provided MnDOT the transparency it needed to make the change to a phased construction decision.

4.3.5 Key Takeaways

The TPI open-book process was particularly successful in establishing the level of trust necessary for MnDOT to make the hard decision to truncate the project’s scope into phases and solicit the additional funding required to complete the project. The survey results showed that the top reason for executing an off-ramp was the contractor’s price exceeding the available funding. This project could have ended in an off-ramp with a substantial delay in the delivery of this critical project. MnDOT created a collaborative atmosphere that leveraged the expertise of both the ICE and the contractor to rescope the project around the contractor’s pricing.

The second key takeaway relates to one factor that created the over-budget chain of events. Risk was not evaluated and accounted for in early budget estimates. Hence, when the CM/GC contractor came on board and provided its risk analysis, the project team was surprised that the costs were significantly over the planning-level estimates.

4.4 Sellwood Bridge Replacement CM/GC Project, Multnomah County, OR

Agency: Multnomah County

Type of Project: Bridge replacement

Delivery Method: CM/GC. “Selected because of schedule issues, technical complexity, third party interface issues, traffic control issues, and the fact that it was easier to incorporate the county’s values into the project using CMGC” (Rowley 2011). Early procurement was needed, and CM/GC permitted the compensation for the early procured materials to be paid by certified invoice.

Initial Budget Value: $160 million

Final Negotiated Value: $158 million

Scope: The owner divided the original scope into the following three work packages:

- – “Work Package 1 – In-Water work and Foundations. Construction of two cofferdams and two foundations/footings in the Willamette River during the in-water work window.

- – Work Package 2 – Bridge Structure. Construction of 1200′ 3-span main structure over water, plus two approaches totaling 750′. Bridge cross section varies to accommodate 2, 3 and 4 traffic lanes, plus two shoulders and sidewalks; width varies 64′ to 90′. Construction must be planned to allow traffic, bicyclists and pedestrians to continue to use this crossing throughout construction with minimal closures (no more than 23 business days). This package also includes: on-bridge utilities, electrical: street and architectural lighting on the new bridge, and demolition of the existing bridge.

- – Work Package 3 – West Side/Highway 43 Interchange and other work. Grade separated modified Single Point Interchange (Tacoma Street with Oregon Highway 43) at the west end of the bridge. Consists of 2,600 LF of 2-lane highway, plus 2-lane off ramps and 1-lane on ramps from the overpass signalized intersection. Interchange includes walls and overpass structure plus two 14′ ramps at 5% connecting bridge sidewalks to regional bike trail 25′ below. Preserve traffic, bicyclist and pedestrian mobility throughout construction. The package also includes landslide mitigation, rock cuts plus retaining walls, drainage and water quality treatment facilities, transition work to Tacoma St. at east end of bridge, traffic signal operations at the west and east ends, 2750 linear feet of regional bike path, and replacement of the Stephens Creek bridge” (Multnomah County 2016).

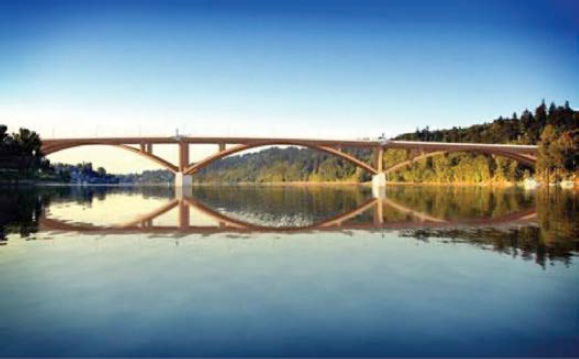

Additionally, the CM/GC contractor was required to participate in the county’s community and business outreach efforts prior to and during construction and develop sustainable practices for implementation during construction. Figure 27 is a picture of the completed bridge.

4.4.1 Sellwood Bridge Goals

The critical project success factor was continuity of traffic during construction. Sustainability was also a key goal for all the aspects of the construction. Finally, community outreach was critical to the project in that neighborhoods on both sides of the river would inevitably be disrupted.

4.4.2 Sellwood Bridge Challenges

The major challenge of this project was the maintenance of traffic during construction. Traffic volumes of up to 30,000 vehicles per day are experienced on the bridge. Both pedestrian and bicycle traffic were to be accommodated as well. The temporary works required for construction involved marine structures and a fixed 4-month window in which the contractor was allowed to work in the river.

4.4.3 Details of the Open-Book Process for Sellwood Bridge Project

Table 8 lists the negotiated elements of the GMP. The details of the other open-book related cost factors are detailed in subsequent paragraphs.

Table 8. Sellwood Bridge negotiated elements of the GMP.

| Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design fee | Profit | Sequence of work | x | ||

| Preconstruction fee | Allowances | Risk | x | ||

| Construction services fee | Equipment rates | x | Contingencies | x | |

| Home office overhead | x | Quantities of work | x | Contract terms | x |

| Project indirect costs | x | Production rates | Schedule | x | |

| General conditions | x | Subcontractor work | x |

Preconstruction Fee: The preconstruction fee was proposed by the contractor during procurement.

Construction Services Fee: This fee was a percentage proposed by the contractor during procurement.

Cost Model: The cost model was developed by the contractor on this project. Quantities were reconciled with the ICE and the designer.

Risk: Risk was quantified using a Monte Carlo simulation. It was then priced into subcontractor bid packages and negotiated for self-performed work as a component of the direct “overall cost of work” defined in the contract.

ICE Involvement: Yes. The ICE’s primary responsibilities were to validate the quantities of work and establish a fair and reasonable cost.

Open-Book Negotiations Result: A mutually agreed-upon construction price was achieved. The contractor proposed to jack the existing bridge 90 feet to the north and use it as the detour route, providing two-way service and allowing the contractor to build the new bridge without the safety issue of work zone traffic. This technique is referred to as a “shoo-fly” bridge. Additionally, the original engineer’s estimate had failed to include the temporary marine works and other temporary construction. The bridge slide saved sufficient money to cover the omissions in the budget estimate, and the project was completed early and within the $160 million bond limit.

Off-ramp: No.

4.4.4 Interviewees Comments

The owner, designer, and contractor were collocated on the project site, which greatly facilitated collaboration among the project team. “The contractor noted that the designer always had the work done on time, which is something not usually experienced by the contractors. Later, it was discovered that liquidated damages clauses were incorporated into the designer’s contract to ensure that the design documents were provided on time. This has not been seen in previous CMGC projects” (Carlson and Gransberg 2018).

“The contractor noted that there seemed to be little need for the engineer’s estimate after award of the preconstruction services contract on this CMGC project because the system requires the CM to develop the quantities and the ICE to validate the quantities. Hence, only the engineer’s current list of pay items and their initial quantities are utilized during cost engineering and budget reviews. The engineer’s pricing seemed redundant. The engineer indicated that its estimates were often discounted by the owner, who had greater confidence in the contractor’s and ICE’s estimates due to the open-book process. FHWA rules were cited by the owner as the reason the engineer was being paid to generate estimates at design milestones” (Carlson and Gransberg 2018).

4.4.5 Key Takeaways

The colocation of the project team resulted in an environment where questions could be asked and answered without the friction of a formal request of information (RFI) system. The owners’ consolidation of the preconstruction service fee and the construction services in the procurement not only provided competitive pricing for those markups but also reduced the open-book negotiation process to one focused on direct cost and risk. The ICE was focused on validating the quantities of work used in the OPCC cost modeling. All entities were given access to each other’s numbers, which reinforced the level of transparency and increased the owners’ confidence that a fair and reasonable price was achieved.

It should also be noted that the owner’s RFP contained a detailed description of the various components of the GMP and their definitions. This allowed the cost model to be developed

around the owner’s standard list of pay items. The work package structure established by the owner facilitated the negotiation of progressive GMPs, which reduced the level of uncertainty within each package.

Using the old bridge as a detour saved both time and cost and enhanced the sustainability of the project by literally recycling the old bridge, thus eliminating the need to consume materials and fuel to build a temporary bridge. The fact that a CM/GC RFP contained evaluation criteria for sustainability encouraged this kind of innovative thinking by the project team.

4.5 I-95 and SR 896 Interchange CM/GC Project, Newark, DE

Agency: DelDOT

Type of Project: Interchange Reconstruction

Delivery Method: CM/GC was selected because the project had many complexities, and it was considered nonstandard work for DelDOT. The complexities included geotechnical challenges (e.g., rock and soft soils), technical structures, and the need to maintain traffic flows through construction.

Initial Budget Value: $120 million

Final Negotiated Value: Not awarded. Off-ramp executed.

Scope: “The interchange is a major congestion point along I-95 and SR 896 corridors in Delaware. Routine and significant backups impact operations and safety along both corridors, particularly during peak traffic periods, which see an AADT of about 127,000 vehicles” (DelDOT 2023).

“The design creates a flyover for SB I-95 traffic to Southbound SR 896 (Ramp C), as well as a flyover from Southbound SR 896 (carrying traffic leaving Newark) to Northbound I-95 (Ramp D). These flyovers remove the existing SR 896 weave condition by reconfiguring Ramps C and D. The Northbound SR 896 to Northbound I-95 ramp (Ramp J) is spaced out from the Ramp D merge onto I-95 so that Ramp J traffic is fully integrated prior to Ramp D traffic merging onto Northbound I-95. Ramp J is realigned and widened to allow for a two-lane exit from Northbound SR 896 and a two-lane merge onto Northbound I-95. Ramp A traffic is added to SR 896 as an additional lane instead of merging into SR 896 Southbound traffic. The Southbound I-95 to SR 896 exit ramp is consistent with a major diverge to account for the projected traffic volumes exiting Southbound I-95 at SR 896. It is a full speed two-lane ramp that quickly opens to add a third lane to separate traffic heading into Newark and traffic heading to Middletown. The Northbound I-95 to SR 896 Ramp (Ramp I/H) is realigned to the existing location of Ramp D, which minimizes right of way and environmental impacts” (DelDOT 2023).

“The project also significantly improves SR 896 connectivity and safety for pedestrians and bicyclists by adding a new multimodal overpass facility that crosses I-95, linking the City of Newark and the University of Delaware on the north to the residential areas located south of I-95” (DelDOT 2023). Figure 28 shows the configuration of the interchange.

4.5.1 I-95 & SR 896 Interchange Goals

“Separating the high-speed SB I-95 toll-bound traffic from the low-speed exiting SR 896 traffic, while lengthening exiting lanes for rush hour backups, improves accessibility and safety and shortens mainline backups. Removing the SB SR 896 weave condition will improve traffic flow and safety on I-95 and SR 896. The project also lengthens the merge onto I-95, lengthens the diverge from NB SR 896, and adds a second lane to Ramp J to improve the backups experienced in the AM rush hour” (DelDOT 2023).

4.5.2 I-95 & SR 896 Interchange Challenges

This is a nonstandard bridge type for DelDOT, and the CM/GC process allowed the team to address many issues they expected to realize during construction. The technical challenges on this project include the following:

- Early geotechnical investigations found that the project would include rock excavation and soft soils that would lead to long settlement times.

- The nonstandard bridge construction allowed DelDOT to prequalify their contractor.

- Maintaining existing traffic flows was a concern, and input from the contractor was needed along with a firm understanding of their means and methods.

4.5.3 Details of the Open-Book Process for I-95 and SR 896 Interchange

Table 9 lists the elements of the negotiated GMP. The details of the other open-book related cost factors are detailed in subsequent paragraphs.

Preconstruction Fee: The preconstruction fee was provided as a stipend, which was identified in the solicitation.

Construction Services Fee: This fee was negotiated.

Cost Model: The cost model was developed by the contractor on this project and fits into the standard DelDOT bid item format. The payment terms also stayed within the standard format.

Risk: A risk register was developed by the team early in the process. The risk register was updated continually. The risk items that could not be eliminated or mitigated were assigned

Table 9. I-95 and SR 896 Interchange negotiated elements of the GMP.

| Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design fee | Profit | Sequence of work | x | ||

| Preconstruction fee | Allowances | x | Risk | x | |

| Construction services fee | Equipment rates | x | Contingencies | ||

| Home office overhead | Quantities of work | x | Contract terms | ||

| Project indirect costs | x | Production rates | x | Schedule | x |

| General conditions | x | Subcontractor work |

ownership prior to the final OPCC. The contractor carried costs for their items in the final bid, and DelDOT held their risks in a contingency, which was included in the project budget.

ICE Involvement: Yes. The ICE’s primary responsibilities were reconciling quantities to align on the project scope. Develop a contractor’s style cost estimate, which was used in comparison with the contractor’s estimate. The ICE services also included constructability reviews, which provide feedback on the risk and assumptions, logs, and review of the contractor’s schedule.

Open-Book Negotiations Result: The negotiations resulted in a price within an acceptable range of the ICE, although the price was 50% over the original budget and the project was not awarded.

Off-Ramp: The off-ramp was exercised since DelDOT did not have the budget to move forward.

Trigger Points for Exercising the Off-Ramp: DelDOT uses three criteria to determine whether a CM/GC project will move into construction. The triggers are budget, cost within an acceptable range of the ICE, and schedule within an acceptable range of the ICE.

4.5.4 Interviewees Comments

Even though the project was off-ramped, the CM/GC process was considered valuable by DelDOT. The CM/GC and the ICE were brought on board at the 60% design phase to start with pricing, constructability reviews, and identification of risks and opportunities. The input from the team improved the quality of plans moving into construction. The CM/GC process that was not awarded established an agreeable price in the $180-million range with an overall duration of 1,350-day schedule. When the DBB contract was advertised, the original CM/GC contractor was the successful bidder. The price came in approximately $20 million more expensive, but the overall duration came down to 800 days.

4.5.5 Key Takeaways

The open-book process provided DelDOT with a transparent cost model, which reflected real-time pricing from the CM/GC and their selected subcontractors and suppliers. Improvements to the plans led to a DBB project, which was readily awardable after the CM/GC process ended. The initial budget was prepared prior to 2020 and did not capture true market conditions realized during design development. DelDOT continues to use the CM/GC process as a delivery method.

4.6 Scofield Avenue Undercrossing SSR CM/GC Project, Richmond, CA

Agency: Caltrans

Type of Project: SSR of existing bridge

Delivery Method: CM/GC was selected because the project was supposed to originally be delivered through DBB. The DBB contract was advertised twice and had an inability to award.

Initial Budget Value: $16.5 million

Final Negotiated Value: $940,101.60 (Package 1) and $15,037,723.57 (Package 2), which included risk assigned to the CM/GC contractor.

Scope: This project is in the city of Richmond on Interstate 580 at the Scofield Avenue Undercrossing in Contra Costa County. The structure is entirely within the Chevron Richmond Refinery complex and passes over pipeline networks feeding the wharf and processing areas of the refinery complex. Figure 29 provides a view of the complexity encountered on the project.

4.6.1 SSR Goals

The purpose of the Scofield Avenue Undercrossing project is to seismically retrofit the under-crossing and address structural vulnerabilities, such as irregularly shaped columns and varying

bent heights. The scope of work includes the retrofit of girder anchorages, hinges, columns, foundations, girders/cap beams, and frame braces.

4.6.2 SSR Challenges

This is a nonstandard bridge type, and its location within the Chevron Richmond Refinery complex raised a significant number of safety concerns. The technical challenges of this project included:

- Contaminated soils;

- Limited staging areas;

- Safety protocols working within an oil refinery complex;

- Access and egress to the site for labor, equipment, materials, and subcontractors;

- Limited use of standard equipment due to tight access, which in turn required more labor resources; and

- Prohibition of impacts to the Chevron Richmond Refinery’s operations.

4.6.3 Details of the Open-Book Process for SSR

Table 10 lists the negotiated elements of the GMP. The details of the other open-book related cost factors are detailed in subsequent paragraphs.

Preconstruction Fee: The preconstruction fee was specified by Caltrans in the solicitation.

Construction Services Fee: This fee was negotiated.

Cost Model: The cost model was developed by the contractor for this project and fit into the standard Caltrans bid item format. The cost model was further detailed and broken down

Table 10. SSR negotiated elements of the GMP.

| Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design fee | Profit | x | Sequence of work | x | |

| Preconstruction fee | Allowances | x | Risk | x | |

| Construction services fee | x | Equipment rates | x | Contingencies | x |

| Home office overhead | x | Quantities of work | x | Contract terms | |

| Project indirect costs | x | Production rates | x | Schedule | x |

| General conditions | x | Subcontractor work | x |

into the following cost components: labor, equipment, permanent materials, construction materials, and subcontractors.

Risk: A risk register was developed by the team early in the process. The risk register was updated continually. The risk items that could not be eliminated or mitigated were assigned ownership prior to signing the contract. The contractor carried costs for their items in the final bid, and Caltrans held their risks in a contingency, which was included in the project budget.

ICE Involvement: Yes. The ICE’s primary responsibilities were reconciling quantities to align on the project’s scope and developing a contractor-style cost estimate, which was used in comparison with the contractors estimate. The ICE services also included conducting constructability reviews, leading the cost reconciliation meetings, providing feedback on the risk and assumptions logs, and reviewing the construction contract.

Open-Book Negotiations Result: Two contracts were awarded with this project. One of the contracts was an early work package, which included removing and disposing sloughing materials and fabricating and welding brackets to be installed at various bents. The final work package completed the SSR of the Scofield Avenue Undercrossing structure.

Off-Ramp: No.

4.6.4 Interviewees Comments

The original advertisement as a DBB project raised a significant number of questions from the contracting community, which led to its initial cancellation. Limitations of operations and safety concerns working within the oil refinery complex increased the complexity of the project. Caltrans worked with the CM/GC during the preconstruction phase to get a firm understanding of the means and methods that would be used during construction. Coordination with the refinery was key in ensuring that construction operations would not affect the refinery’s operations. On this project, the CM/GC contractor specialized in complex bridge construction. The project was considered successful by all parties involved post construction.

4.6.5 Key Takeaways

The open-book process provided Caltrans with the means and methods that would be used by the contractor during construction. This information was shared with the refinery to ensure expectations were set and met during the construction phase.

4.7 Bangerter 4700 S Interchange PDB Project, Salt Lake City, UT

Agency: UDOT

Type of Project: Roadway and Bridge

Delivery Method: PDB was selected because the scope included the relocation of a section of the Jordan Valley Aqueduct, which provides drinking water to 500,000 people. PDB allowed UDOT to address this work as an early work package and complete the project one year earlier than traditional D-B would allow.

Initial Budget Value: $110 million

Final Negotiated Value: $106,273,233

Scope: “Over the last 10 years, UDOT has been progressively upgrading the various intersections of Bangerter Highway to freeway-style interchanges. Upgrading the intersection of 4700 South and Bangerter Highway is the next steps in UDOT’s efforts to reduce congestion and improve quality of life on the west side of the valley. Once all intersections of Bangerter

Highway have been upgraded, this facility will reduce travel times for drivers, providing an alternative to I-15” (UDOT 2022). The major scope components project included:

- – Relocation of the Jordan Valley Aqueduct;

- – Utility relocations;

- – Conversion of an at-grade intersection to a freeway-style interchange; and

- – Design and construction of a new bridge and ramps, noise walls, and lighting, signals, and signage.

Figure 30 provides a rendering of the project.

4.7.1 Bangerter 4700 S Interchange Goals

The critical project success factor was relocating the Jordan Valley Aqueduct while minimizing disruptions to the drinking water supply to the affected community. Other goals were providing a detour plan for traffic when the existing at-grade intersection was demolished.

4.7.2 Bangerter 4700 S Interchange Challenges

The major challenge of this project was the disruption to the community. Traffic volumes of up to 10,000 vehicles per day are experienced at the intersection of the major arterial road (4700 South) and Bangerter Highway. “The Jordan Valley Aqueduct consists of 6-ft wide underground pressurized pipeline that extends nearly 40 miles from the mouth of Provo Canyon to 2100 South in Salt Lake City” (UDOT 2022).

The aqueduct had to be entirely relocated in a short window of time within the calendar year, and it needed to be relocated before work could begin on the proposed interchange. Furthermore, the pipe material required for the pressurized aqueduct is specialized material and can take a year to procure. Therefore, relocating the aqueduct as soon as possible was critical to completing the project on schedule.

4.7.3 Details of the Open-Book Process for the Bangerter 4700 S Interchange Project

Table 11 lists the negotiated elements of the GMP. The details of the other open-book related cost factors are detailed in subsequent paragraphs.

Table 11. Bangerter negotiated elements of the GMP.

| Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design fee | x | Profit | x | Sequence of work | x |

| Preconstruction fee | x | Allowances | x | Risk | x |

| Construction services fee | x | Equipment rates | x | Contingencies | x |

| Home office overhead | x | Quantities of work | x | Contract terms | x |

| Project indirect costs | x | Production rates | x | Schedule | x |

| General conditions | x | Subcontractor work | x |

Preconstruction Fee: The preconstruction fee was negotiated with the design-builder.

Construction Services Fee: This fee was negotiated with the contractor.

Cost Model: The cost model was jointly developed on this project. Quantities were reconciled down to the activity level. The project was treated as a traditional DB: It was paid on a schedule of values tied to the project schedule.

Risk: Risk was included line by line, and both parties were required to manage. Ownership was assigned along with a trigger used for payment and paid as a lump sum or contingency items were developed at unit pricing.

ICE Involvement: Yes. The ICE’s primary responsibilities were to compare and validate the project scope and establish a fair and reasonable cost. The ICE developed a production-based contractor-style cost estimate in a modified double-blind cost reconciliation process.

Open-Book Negotiations Result: A mutually agreed-upon construction price was achieved.

Off-Ramp: No. UDOT policy is an off-ramp that can be triggered when the contractors proposed GMP exceeds more than a 5% variance of the ICE’s estimate. Market schedule and conditions are carefully considered and accounted for prior to taking the off-ramp.

4.7.4 Interviewee Comments

Open-book negotiating procedures available through PDB permitted the development of an early works package to relocate the Jordan Valley Aqueduct. By accelerating this relocation, the project was completed one year early. Other efficiencies leveraged during the open-book process allowed the project to also be completed under its initial budget. UDOT uses a construction price facilitator, independent of the ICE, to identify items for discussion and reconciliation. Neither the PDB nor the ICE see the other teams’ pricing except for select items identified by the construction price facilitator.

4.7.5 Key Takeaways

The open-book process involved a double-blind evaluation of the PDB’s and ICE’s estimates by UDOT and the construction price facilitator. A variance of more than 5% from the independent cost estimate triggers an action to reevaluate the basis for each entity’s construction price proposal. The construction price facilitator facilitates the process. The double-blind process creates independence between the entities involved, thus establishing the GMP. However, UDOT uses the approach to eliminate a potential bias towards trusting the ICE’s estimate over the PDB’s. UDOT has completed 64 D-B projects since 1998, 30 CM/GC projects since 2005, and four PD-B projects since 2018. The double-blind yet facilitated open-book process has only been used on the last two PDB projects; however, it has proven to be extremely effective and efficient in negotiating a fair and reasonable price and schedule for the project.

4.8 I-270 ICM PDB Project, Montgomery and Frederick Counties, MD

Agency: MSHA

Type of Project: Congestion management systems

Delivery Method: PDB was selected because the scope was not fixed while the budget was. MSHA wanted to encourage innovation in the technologies installed while limiting the cost to a stipulated sum. PDB allowed the scope of work to be negotiated and progressively priced via the open-book process.

Initial Budget Value: $100 million

Final Negotiated Value: $118 million

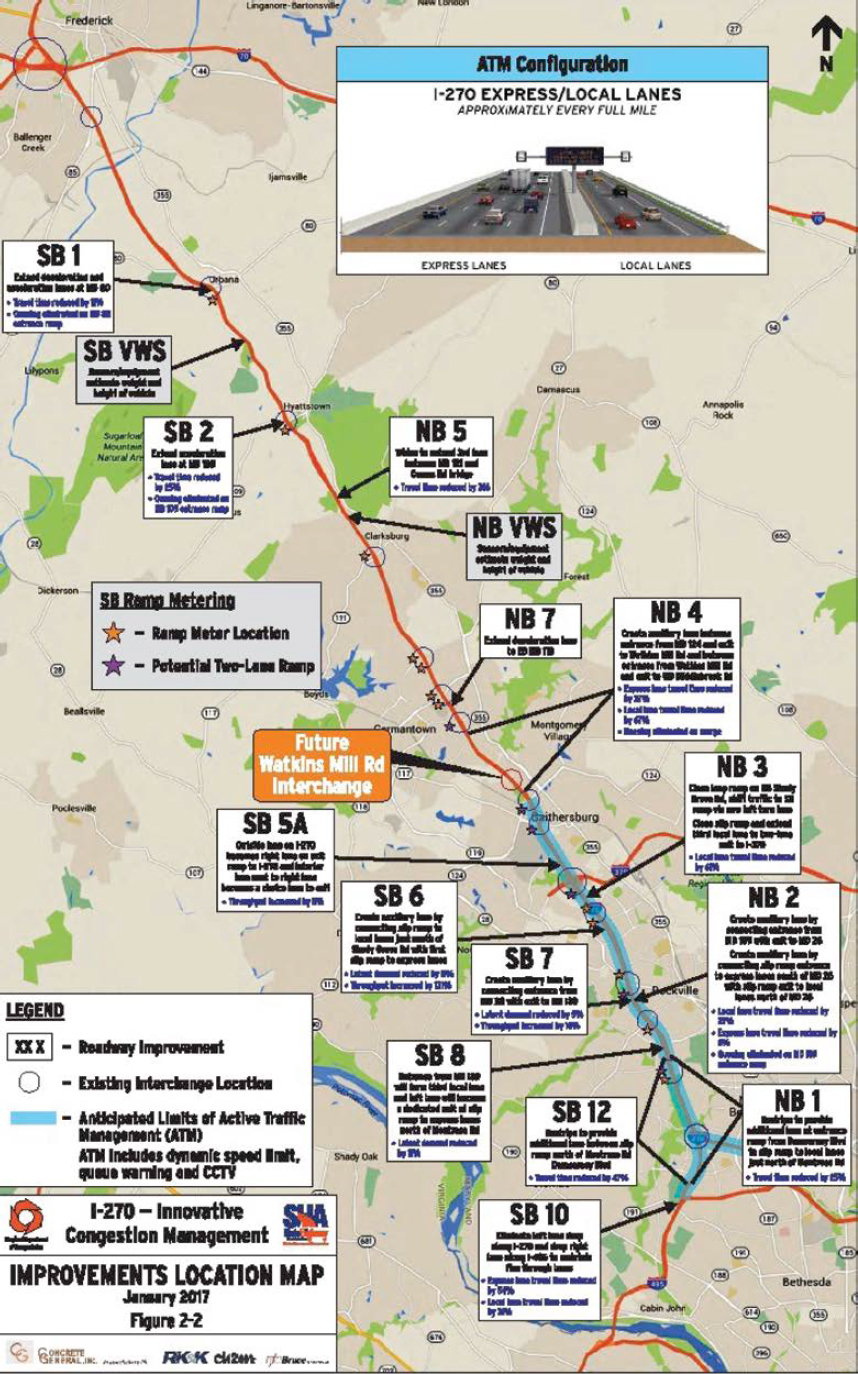

Scope: “The project area is the I-270 corridor from IS 495 (including the I-270 spur) to I-70. The study corridor is one of the most congested in Maryland with average daily traffic of approximately 240,000 in many segments. Over saturated conditions and extended peak periods greatly impact travel time reliability” (MSHA 2023).

4.8.1 ICM Goals

“The contract is intended to address the following goals:

- Mobility – Provide improvements that maximize vehicle throughput, minimize vehicle travel times, and create a more predictable commuter trip along I-270.

- Safety – Provide for a safer I-270 corridor.

- Operability/Maintainability/Adaptability – Provide improvements that minimize SHA operations and maintenance activities while being adaptable to future transportation technological advancements.

- Well-Managed Project – Provide a Project Management and Work Plan that addresses communications, coordination and risk management, achieves a collaborative partnership with all members of the project team and stakeholders” (MSHA 2023).

Figure 31 provides an overview map of the project.

4.8.2 ICM Challenges

The major challenge of this project was developing and meeting the pragmatic performance criteria for the traffic engineering systems to be employed. Major elements of the project scope are as follows:

- High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Lanes

- – The inside travel lane of I-270 functions as an HOV lane from 6:00 am to 9:00 am in the southbound directions from I-370 to I-495 and from 3:30 pm to 6:30 pm in the northbound direction from IS 495 to MD 121. HOV usage on I-270 will be required to be maintained for the existing longitudinal limits as part of this contract. Lateral shifts of the HOV lane will require an equivalency study and approval by FHWA.

- Maximize the scope within the budget.

- – Implement Innovative Congestion Relief strategies and technologies to the maximum extent within the means of the budget.

- Coordination with other projects

- – The Watkins Mill Interchange Project is within the contract limits. Depending on the proposed Innovative Congestion Management (ICM) scope, coordination with that project may be required to ensure compatibility. Any redesign, and associated permit modifications, of the Watkins Mill Interchange will be performed by MSHA.

- National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) / Maryland Environmental Policy Addendum 30 6 -1017—0290-1166 Act (MEPA)

- – Project(s) will require NEPA approval from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) when federal actions will be required (e.g., design exceptions, Interstate Access Point Approval [IAPA]). If no federal action is required, then MEPA approval will be needed. Multiple environmental documents may be developed for the contract. Each separate project for an environmental document must be a standalone construction project that connects logical termini and be of sufficient length, have independent utility, and not restrict consideration of alternatives for other reasonably foreseeable transportation improvements. Any NEPA/MEPA document will be prepared by MSHA. The Design-Builder will have no decision making responsibility with respect to the NEPA/MEPA process but will provide information needed about the project and possible mitigation actions.

- – Public Involvement will be needed as part of NEPA/MEPA and should ensure travel shed is covered, not just the immediate project area.

- – The requirements of the MSHA Noise Policy must be met for the Design-Builder’s improvements. Department of Natural Resources managed land (Seneca Creek State Park) is within the contract limits.

- Minimize Environmental Impacts

- – No permits have been obtained. Agency coordination will be required to secure necessary permits for any environmental impacts.

- – The Design-Builder will prepare permit applications for submittal by the Administration. Environmental impacts due to Design-Builder’s project should be minimized to the extent practical. Mitigation may be required by permitting agencies depending on impacts to environmental features as a result of Design-Builder’s project.

- Minimize utility and property impacts and relocations

- – Utility and property impacts due to Design-Builder’s project should be minimized to the extent practical.

- – All costs for third party utility relocations and property impacts will be subtracted from the fixed value contract” (MSHA 2023).

4.8.3 Details of the Open-Book Process for ICM Project

Table 12 lists the negotiated elements of the GMP. The details of the other open-book related cost factors are detailed in subsequent paragraphs.

Design and Preconstruction Services Fee: The preconstruction fee was proposed as a lump sum during procurement by the design-builder.

Construction Services Fee: This fee was negotiated with the contractor.

Cost Model: The cost model was jointly developed on this project. Post-award collaboration between the ICE, design-build team (DBT), and MSHA resulted in the final model.

Table 12. ICM negotiated elements of the GMP.

| Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design fee | x | Profit | Sequence of work | ||

| Preconstruction fee | Allowances | Risk | x | ||

| Construction services fee | x | Equipment rates | x | Contingencies | x |

| Home office overhead | Quantities of work | x | Contract terms | x | |

| Project indirect costs | Production rates | x | Schedule | x | |

| General conditions | x | Subcontractor work | x |

Risk: All the construction agreed price (CAP) packages were negotiated as a lump sum for the completion and delivery of all services. In most cases, a CAP would not be proposed or requested until the design had been advanced enough to address any associated risks to the best ability possible. If risk existed that could not be fully addressed or mitigated, discussions were held during the CAP negotiations regarding who to assign the risk to or how they could possibly be shared. If they were shared, a contingency item via a risk-sharing pool could be established. For example, roadway patching, which became necessary during the execution of the field work, was addressed via a contingency risk-sharing item.

ICE Involvement: Yes. The ICE’s primary responsibilities were to collaborate with the owner and contractor on the development of the cost model for each individual CAP package, review the design and specifications from a constructability and biddability standpoint, develop a “contractor’s style” estimate for each package concurrent to the contractor once a CAP was requested or proposed, advise MSHA and review the DBT’s CAP proposal reasonability, and participate in the negotiations to discuss and understand the differences between the ICE estimate and the DBT estimate on a given CAP.

Open-Book Negotiations Result: A mutually agreed-upon construction price was achieved.

Off-Ramp: No. An off-ramp was not utilized because the cost negotiations were unsuccessful. However, the MSHA did remove scopes of work from the project compared to what the DBT proposed because of either conflicts with upcoming anticipated work or programmatic budgetary concerns for MSHA. Two work packages were advanced to Plans, Specifications, and Estimates (PS&E) and eliminated from the overall scope of work to be bid later.

4.8.4 Interviewee Comments

This project, although listed as a PDB, is a little different than other PDB projects in that it did include a specific (i.e., predetermined) budget for the DBT to propose to and stay within. Following procurement, additional funding was approved for the project to install ramp metering in both the northbound and southbound direction. The selected DBT’s proposal only included ramp metering in the southbound direction because that presented the most value within the stipulated budget. The project also involved a third fee for ROW acquisition and utility relocation required by the design-builders’ final technical design.

4.8.5 Key Takeaways

The open-book process involved negotiating within a stipulated maximum sum. Thus, the competing design-builders needed to balance their design approach with its impact on ROW and utilities to stay within the stipulated maximum amount. The MSHA’s approach to using the open-book negotiation process via the progressive development and negotiation of lump sum work packages provided it with necessary technical, schedule, and cost information to feel certain that the CAP packages were fair and reasonable. As a result, the total cost of the project was never in question. However, the final scope of work was optimized with the available budget.

The PDB process was flexible enough to allow the design-builder to advance two packages to PS&E, price them, and then remove them from the ICM project to be procured by DBB when additional funding was authorized.

4.9 BDBR PDB Project, Wilsonville, OR

Agency: City of Wilsonville (CW), Oregon

Type of Project: Roadway and Bridge

Delivery Method: PDB was selected because of the complexity of the bridge and creek work, the staging complexities of the three interrelated roadway projects, and the need to complete these projects within the same time frame.

Initial Budget Value: $18.2 million

Final Negotiated Value: $24.4 million

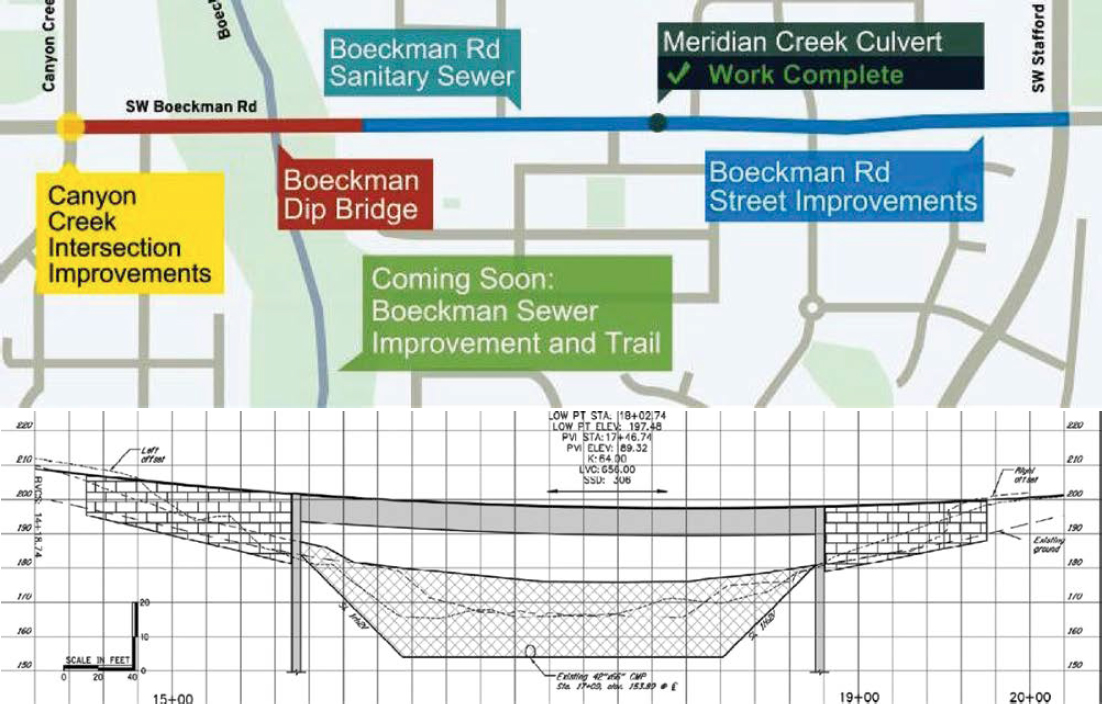

Scope: This PDB contract bundles five roadway and utility projects with the Boeckman Dip Bridge Replacement to upgrade the Boeckman Road Corridor. The project upgrades a section of the Boeckman Road constructed in the 1960s. The individual projects are as follows:

- The Boeckman Dip Bridge Replacement will:

- – Construct a new bridge over Boeckman Creek;

- – Upgrade the existing steep, narrow, and rural roadway to an urban standard;

- – Reduce the slope of the roadway and improve visibility for drivers, pedestrians, emergency responders, and transit vehicles;

- – Build safe bicycle and pedestrian facilities to make it safer and easier to walk, run, and cycle;

- – Remove culvert for future projects to improve fish passage; and

- – Enhance the creek’s natural resources and treat stormwater for improved water quality.

- The Boeckman Creek Regional Trail Connection will:

- – Construct a section of the Boeckman Creek Regional Trail between the new bridge and Frog Pond. Future construction will connect the trail to Memorial Park.

- The Boeckman Road Sewer Improvements will:

- – Construct approximately one-half mile of new sanitary sewer trunk on Boeckman Road to serve the Frog Pond area. The new sewer will connect existing sewer lines between the new bridge on the west and Wilsonville/Stafford Roads on the east.

- The Boeckman Road Street Improvements will:

- – Improve the existing roadway between Canyon Creek Road and the Wilsonville/Stafford intersections to accommodate all users—drivers, riders, pedestrians, and cyclists. The design will incorporate elements of Safe Routes to Schools for the future primary school and Meridian Creek Middle School and protected crossing elements for neighborhood connections.

- The Canyon Creek Road/Boeckman Road Intersection Improvements will:

- – Construct a traffic signal or roundabout at the intersection of Canyon Creek Road and Boeckman Road to relieve congestion, improve safety and traffic flow.

- The Stafford Road/SW 65th Avenue/Elligsen Road Intersection: To mitigate traffic impacts during the closure of Boeckman Road for the bridge’s construction, a temporary traffic signal will be installed to detour traffic at the Stafford Road/SW 65th Avenue/Elligsen Road intersection.

Figure 32 provides the details of the bundled projects and cross-section view of the bridge.

4.9.1 BDBR Goals

The primary goal was to increase safety on Boeckman Road by addressing inadequate sight distance on a vertical curve that did not meet AASHTO standards. Sidewalks and bicycle lanes were needed on both sides of the road to further enhance the safety of pedestrians and cyclists. Additionally, by replacing the existing culvert under the embankment with a bridge, the impediment to fish passage on Boeckman Creek to the Willamette River was improved and set the stage for a follow-on streambed improvement project. Finally, the CW wanted to optimize the phasing of the individual projects as a means to minimize disruption to the traveling public.

4.9.2 BDBR Challenges

The major challenge of this project was minimizing disruption to the community. The bridge construction required a full closure of Boeckman Road. Two detour plans needed to

be assessed to determine which furnished the best alternative. The project is in an environmentally sensitive area, and the goal is to return Boeckman Creek to its natural state while improving water quality.

4.9.3 Details of the Open-Book Process for BDBR Project

Table 13 lists the negotiated elements of the GMP. The details of the other open-book related cost factors are detailed in subsequent paragraphs.

Preconstruction Fee: The preconstruction fee was negotiated with the contractor.

Construction Services Fee: This fee was negotiated with the contractor.

Table 13. BDBR negotiated elements of the GMP.

| Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated | Element | Negotiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design fee | x | Profit | Sequence of work | x | |

| Preconstruction fee | x | Allowances | Risk | x | |

| Construction services fee | x | Equipment rates | Contingencies | x | |

| Home office overhead | Quantities of work | x | Contract terms | ||

| Project indirect costs | x | Production rates | Schedule | x | |

| General conditions | x | Subcontractor work | x |

Cost Model: The cost model was developed by the contractor on this project. The project was treated as a traditional lump sum DB: It was paid on a schedule of values tied to the project schedule.

Risk: A risk register was jointly developed and used to quantify the expected value of each risk. The total value became the contingency, and the CW controlled the allocation, which was incrementally included in the GMP as risks were realized.

ICE Involvement: Yes. The ICE’s primary responsibilities were to compare and validate the project scope and establish a fair and reasonable cost. The ICE also developed a bottoms-up contractor-style cost estimate.

Open-Book Negotiations Result: A mutually agreed-upon construction price was achieved.

Off-Ramp: No.

4.9.4 Interviewee Comments

Because of scheduling difficulties, interviews with the owner were not conducted. Thus, the following interview comments are from the contractor.

The contractor believed that PDB was the correct delivery method selection and that the open-book process greatly facilitated the CW’s understanding of the change in market conditions since the 2019 budget estimate. Additionally, the final scope of work was negotiated in light of the construction means and methods needed and the corridor phasing plan, which also drove the schedule. Awarding the project with minimal design completion allowed the PDB contractor to implement alternative technical concepts for the bridge that optimized its cost with the need to minimize traffic disruption.

4.9.5 Key Takeaways

The open-book process provided the necessary transparency to determine the current costs of various technical and sequence-of-work alternatives. The bundling of this group of previously authorized projects creates a situation in which the PDB contractor controls the sequence of work along the corridor and can better coordinate the efficient completion based on the demand for the traffic.

4.9.6 Findings from the Case Examples

A major finding of this chapter is that employing open-book negotiating procedures encourages a collaborative environment, which in turn provides the owner with confidence in the contractor’s proposed GMP, even if it is much greater than the approved budget. This finding was shown in six of the nine case examples (LBB, BDBR, CMCR, ICM, TPI, and I-95/SR 896). In the LBB project, the off-ramp was exercised; however, the owner cited the open-book process as valuable in that it showed that the budget estimate was in error and missing key scope elements. The ICM project used this knowledge to advance the design on two packages to PS&E before deleting them from the initial scope of work, which eliminated the design liability issues with reprocuring the two packages as DBB projects. Hence, the open-book negotiation process appears to provide the owner with a clearer understanding of current market pricing and facilitates an informed decision on off-ramp execution or the return to upper management to seek additional funding.

It is notable that all nine case examples chose to retain an ICE, which lends credence to the notion that having an ICE adds value to the open-book process. Likewise, employing an ICE provides the owner with not only a third OPCC but also a demonstration of its investment in determining a fair and reasonable price for the final GMP. Four of the nine case examples

(LBB, TPI, I-95/SR 896, and BDBR) mentioned this benefit. TPI was a prime example of this finding. With the ICE and the contractor’s numbers within 2% of each other, MnDOT chose not to execute an off-ramp but to change the delivery to phased construction. It went on to use the ICE and the CM/GC contractor to furnish a cost-optimized scope of work for the Phase 1 project and a value and scope of work for Phase 2. The Phase 2 value was used to secure additional funding. The CM/GC contractor was eventually awarded both Phase 1 and Phase 2, a testimony to the owner’s confidence in the transparency afforded by open-book negotiations.

The establishment of the preconstruction and construction services fees is a matter of individual agency preference. Seven of the eight case examples included one or both fees as part of the procurement, either as a fixed percentage set by the owner or by requiring the contractor to propose the fee. Fixing those costs in the procurement has two advantages. First, it provides an element of competition to the establishment of those fees. Secondly, it puts the focus of the open-book negotiations on the measurable quantities of work, avoiding issues regarding which elements of overhead and general conditions are appropriate.

Only two cases, Sellwood Bridge and TPI, went beyond establishing a risk register and computing the expected value of risk based on professional judgment. The dialogue involved in a joint risk register development may be the reason the more rigorous Monte Carlo simulation was deemed to be unnecessary in the other cases. If the owner details how risk will be used to determine contingencies and its process for allocating risk in the CM/GC and PDB contract, the dialogue on risk and contingencies can facilitate a negotiated solution for the rules of accessing project contingencies. The dialogue on risk can also facilitate the alignment of expectations and further enhance collaboration.

Like the fees, each individual agency has its own method for establishing and administering contingencies. In some cases, like Sellwood and ICM, the negotiated contingencies for contractor risk were assigned to the GMP in some form. Overall, the agencies preferred to retain contingencies outside the GMP and control their application on a case-by-case basis.

In the CMCR, SSR, BDBR, and TPI case examples, the owner expressed that they believed the contractor was better prepared to negotiate. By recognizing that this sentiment will often be the case due to public agency staffing constraints, the owner can mitigate this issue by taking control of the content of the negotiations and providing a detailed description of the open-book process, the components of the GMP, and how risk and contingencies will be addressed in the project solicitation. Examples from the FDOT and VDOT are presented in Appendix C to provide two possible guidelines for adapting to a specific DOT. The case examples also indicate a need for future research regarding the preparation and training needed by the owner’s negotiating staff.