Off-Lake Sources of Airborne Dust in Owens Valley, California (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

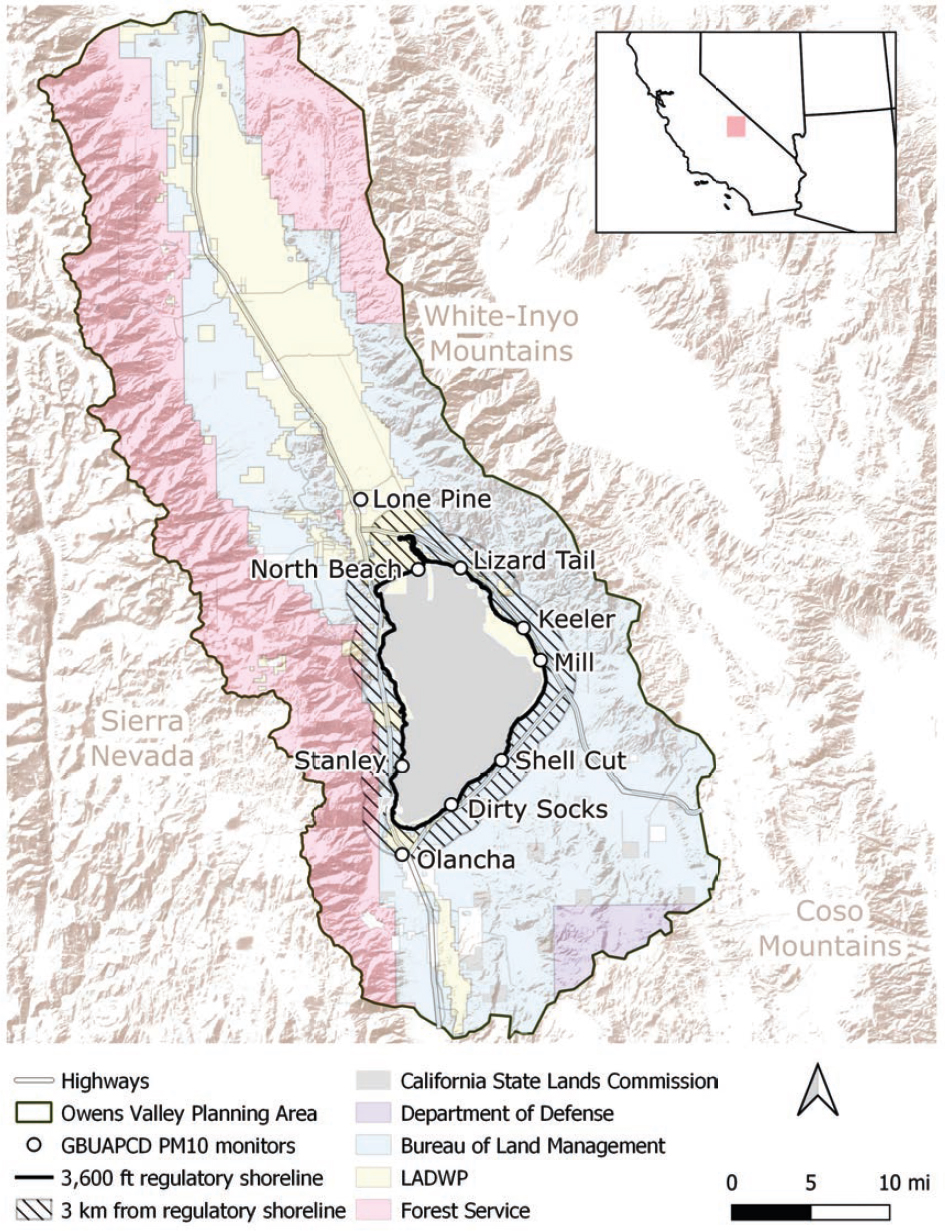

Owens Lake, or Patsiata in the local Mono language, is located at the southern end of the Owens Valley and bordered by the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the west, the White-Inyo Mountains to the east, and the Coso Range to the south and east (Figure 1-1). Prior to the 20th century, the lake was a closed-basin saline lake of approximately 100 square miles (Holder 1997; NASEM 2020). The lake was and still is central to the way of life for the Nüümü and Newe (Paiute and Shoshone in English, respectively) who live in Owens Valley, or Payahuunadü, land of the flowing water (Owens Valley Indian Water Commission 2024). Beginning in 1913, water was diverted from the Owens River into the Los Angeles Aqueduct. This diversion eventually shrank Owens Lake to one-third of its former area, leaving a brine pool surrounded by a dry lakebed (NASEM 2020). Once exposed, the lakebed produced large amounts of airborne dust under high winds. This resulted in Owens Lake being one of the largest sources of airborne particulate matter in the United States (EPA 2017; Ono 2006), including particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 10 micrometers or less (PM10). These small particles can penetrate the lungs and can cause or worsen a variety of health problems such as asthma, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and respiratory infections (GBUAPCD 2016). In 1987, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identified the southern Owens Valley (known as the Owens Valley Planning Area, or OVPA) as violating the health-based PM10 National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) (GBUAPCD 2016). The area also has been designated by the state of California as being in nonattainment of the corresponding state standards, the California Ambient Air Quality Standard (CAAQS) (NASEM 2020).1

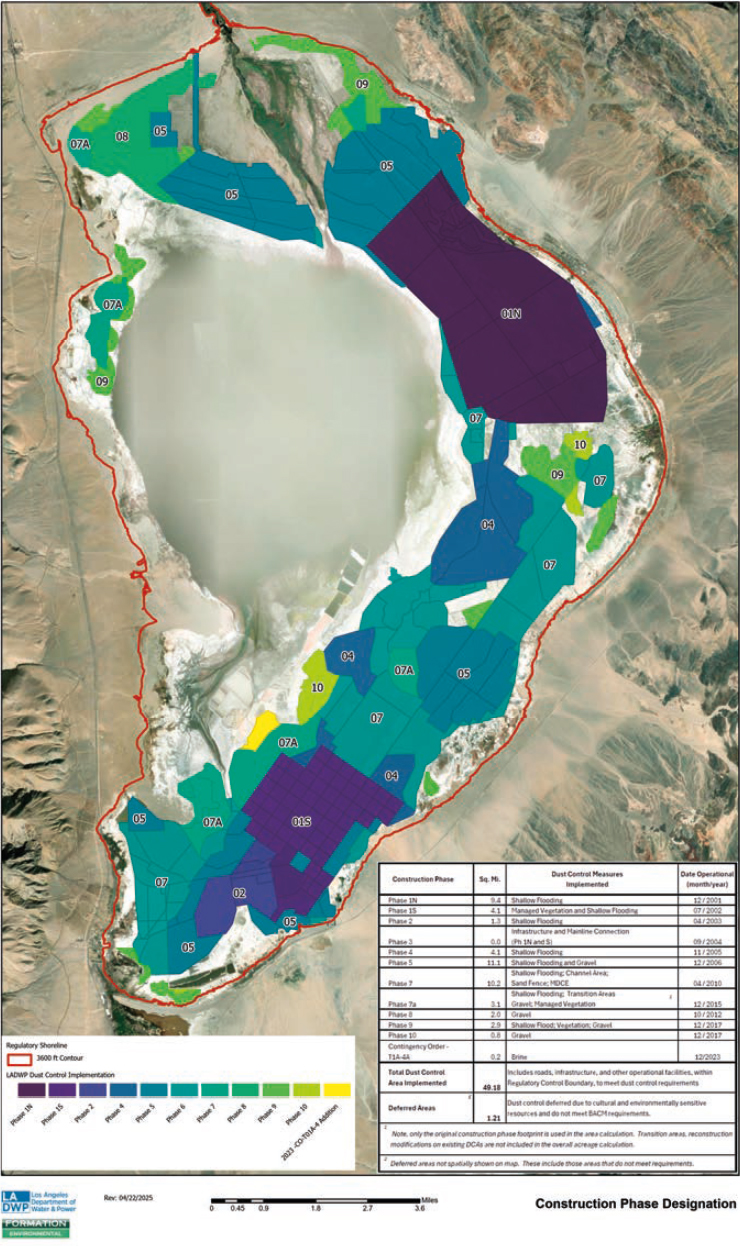

Over the last 25 years, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP), at the direction of the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District (the District), has implemented dust control measures on the lakebed, defined as the land located below the regulatory shoreline, which was designated at an elevation of 3,600 ft (GBUAPCD 2016). These dust control methods were implemented with the objective of meeting the EPA NAAQS for PM10, as well as the PM10 standards set by the state of California. There have been four approved final State Implementation Plans (SIPs)—1998, 2003, 2008, 2016—and an amendment in 2013, that documented how PM10 emissions would be reduced to comply with the NAAQS (GBUAPCD 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, 2016). As of this publication, LADWP has spent approximately $2.5 billion on their dust mitigation program at Owens Lake and implemented controls on 49.18 square miles (including 1.21 square miles of deferred areas) with a

___________________

1 Attainment of the National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) has precedence over attainment of the California Ambient Air Quality Standard (CAAQS). Unlike NAAQS, CAAQS does not require that standards be met by specified dates. Instead, the law requires incremental progress toward attainment (CARB 2024).

NOTES: Hatch-markings delineate the area within 3 km of the 3,600-ft-elevation regulatory shoreline that defines the Owens Lake bed. Three kilometers are shown here based on the panel’s statement of task, which states, “the majority of the local off-lake sources fall within 2–3 km from the shoreline….”

potential maximum buildout extent of 53.4 square miles (Figure 1-2) (LADWP 2024b). These controls will be maintained in perpetuity. The District has also implemented approximately 140 acres of dust control measures on off-lake areas (above the 3,600-ft-elevation regulatory shoreline) at the Keeler Dunes following a $10 million public benefit contribution from LADWP and $2.6 million from District funds (GBUAPCD 2013) (Grace Holder, GBUAPCD, personal communication, May 2024). Together, these controls have made substantial progress toward reducing the frequency and intensity of exceedances of the PM10 standard, currently monitored at 9 locations surrounding the lakebed (Figures 1-2 and 1-3). Despite these efforts, both on-lake and off-lake sources continue to cause PM10 exceedances.

STATEMENT OF TASK AND APPROACH

The Owens Lake Scientific Advisory Panel (OLSAP) was established following the 2014 stipulated judgment between the District and LADWP. The goal of the panel is to foster understanding and collaboration on the scientific and technical approaches to dust control. The panel’s first report (NASEM 2020) focused on the effectiveness of alternative dust control methods for on-lake sources of PM10. Since that report, the OVPA has seen continued exceedances that have prevented attainment with the PM10 NAAQS, which requires no more than one expected exceedance per year at each monitor, averaged over 3 years (40 C.F.R. § 50.6[a] 2023) (see also Chapter 3). As shown in Figure 1-3, these continued exceedances are increasingly dominated by off-lake sources. In 2022, the District sent a letter to LADWP and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine requesting that OLSAP examine and evaluate PM10 emissions from off-lake sources. The full statement of task is found in Box 1-1.

Given the focus of the statement of task on the PM10 NAAQS and not the CAAQS, the panel focused much of its analysis on attainment of the NAAQS. However, the panel recognizes that attainment of the CAAQS is an eventual goal. Additionally, while both on-lake and off-lake sources can and do contribute to varying degrees to PM10 exceedances on individual monitored exceedance days, the statement of task solely focuses on off-lake sources (i.e., those that are above the 3,600-ft-elevation regulatory shoreline). Although the District emphasized that the primary focus of the statement of task is local off-lake sources that are primarily within 2–3 km of Owens Lake (Table 1-1),2 the panel also considered other sources in the Owens Valley Planning Area “for which available data indicate [as] potentially significant contributors to high PM10 concentrations in the Owens Valley Planning Area (OVPA).” Additionally, the panel considered potential future sources as the task mandates that the panel consider “changes in off-lake dust sources over time” (Box 1-1). The District also noted that windblown sources of dust are the focus of the task, not local permitted sources of air pollution (e.g., landfills, mines) nor other local sources of dust from mechanical and combustion processes (e.g., woodburning devices, transportation, unpaved roads, paved road dust, tailpipe emissions, prescribed burning) (Table 1-1). Similarly, regional dust events originating from outside of the OVPA and wildfire smoke events are not the main focus of the task, although these ancillary sources of PM10 may be relevant to the discussion, as they can contribute to exceedances in the OVPA (Table 1-1). Finally, as suggested by the statement of task, the panel only considered the potential application of the Exceptional Events Rule (40 C.F.R. § 50.14) to high wind dust events and not for wildfire smoke events.

OLSAP used numerous resources, including published literature, regulatory documents, presentations, and public comments in its information gathering. The panel held several information-gathering meetings, including a 2-day open session at Owens Lake May 29–30, 2024, where several science and policy experts, Tribal representatives, and environmental organizations presented to the panel. Another open information gathering session occurred in Los Angeles on July 30, which included presentations from experts on the hydrology, climatology, and emissions of Owens Valley. Another open information gathering session occurred on October 7 and focused on exceptional events in Imperial County, Clark County, and the South Coast Air Quality Management District. Virtual open

___________________

2 The focus on 2–3 km from the regulatory shoreline follows the 2016 State Implementation Plan (GBUAPCD 2016) that was based on an analysis by the Maricopa Association of Governments, which found source impacts decay by about a factor of “10 between 0 and 500 meters, between 500 and 2,800 meters, and between 2,800 and 30,000 meters.” This analysis is likely valid for smaller source areas, but may not be for more disperse sources, or when those emissions are channeled down the valley.

NOTES: Only the original dust control phases are included and several of the dust control areas have been transitioned to other types of dust control or have been rebuilt/redesigned. Changes to acreages caused by redesigns are not shown or included in the acreage calculation.

SOURCE: Arrash Agahi, LADWP, personal communication, January 2025.

NOTES: These data do not reflect official exceedance counts, but this analysis was conducted to understand long-term trends using consistent metrics. This plot takes into account the fact that monitors have been added over time, and some monitors were temporarily removed. For example, the Lizard Tail and North Beach monitors were not installed until 2008–2009. The Flat Rock PM10 monitor, which was in place from 2001 to 2011, was replaced by the Mill monitor in 2010. The Mill and North Beach monitors were temporarily removed from December 2012 through August 2014, and the Dirty Socks monitor was removed from December 2012 through December 2014. Exceedance counts and on- and off-lake attribution are based on screened wind direction and a threshold of 150 µg/m3 for exceedances. For all years, on- and off-lake exceedance counts were purely classified by screened wind directions and may have included wildfire smoke events and regional events. For all hours without data when the wind was coming from an opposite direction (on- or off-lake), a background concentration of 20 µg/m3 was assumed. Many years have incomplete data and are not a true indication of annual exceedance counts, especially in years in which a monitor was installed or removed. A statistically significant decreasing trend in the number of exceedances per monitor was determined for on-lake emissions (p-value<0.01) but the trend for off-lake exceedances was not as significant (p-value=0.03) using the non-parametric Mann-Kendall statistical test. However, if the first 2 years of data (2001–2002) are removed, the off-lake trend is no longer significant (p=0.15).

SOURCE: Generated by the panel. Data from Chris Howard, GBUAPCD, personal communication, March 2024.

sessions were held on July 12, July 26, September 6, and December 16, 2024, to investigate air quality data, strategies for engaging with Tribal communities, and dispersion modeling results in more detail.

In a few cases, the panel completed original data analyses. The results of these analyses were replicated by fellow panel members to verify accuracy. This involved multiple panel members and project staff replicating the classification of data in the District’s exceedance database, and the panel also performed a comparative analysis of emission fluxes, including derivation of equations and code, shown in Appendix A.

OUTLINE OF REPORT

The report is organized into six chapters. Chapter 2 discusses the system-level context for off-lake PM10 sources. Chapter 3 explores the sources of PM10 exceedances in the OVPA and provides recommendations on how to improve monitoring and modeling. Chapter 4 provides several conclusions on the origin and evolution of

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

The Owens Lake Scientific Advisory Panel (OLSAP) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will evaluate off-lake sources of airborne dust in Owens Valley, California. Off-lake dust sources are those that are located at elevations above the 3,600-ft regulatory shoreline of Owens Lake. OLSAP will focus on those sources for which available data indicate they are potentially significant contributors to high PM10 concentrations in the Owens Valley Planning Area (OVPA). (PM10 refers to airborne particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 10 micrometers or smaller.)

As part of its assessment, and to the extent sufficient data are available, OLSAP will summarize the overall nature and character of off-lake sources. The majority of the local off-lake sources fall within 2–3 km from the shoreline as used in the air modeling conducted for the 2016 State Implementation Plan (SIP) for achieving and maintaining the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) in the OVPA. In addition, the panel will address the following aspects with respect to off-lake dust sources:

- Develop a summary of previous research, studies, and available information on off-lake dust sources in the OVPA that synthesizes the overall character of off-lake dust sources, including (but not limited to):

- Physical setting and other characteristics, such as geomorphological features.

- Extent and distribution of off-lake sources.

- PM10 impacts of off-lake sources, with impacts defined as causing or significantly contributing to exceedances of the PM10 NAAQS in the OVPA.

- Past and expected future changes in off-lake dust sources over time. Consideration of changes may include emissivity, number, extent, and distribution of off-lake sources.

- Describe the origin of regulatorily significant off-lake dust sources and how they developed over time.

- Describe potential options and recommendations to better characterize, monitor, and track changes in the PM10 contributions of off-lake sources to exceedances of the PM10 NAAQS in the OVPA.

- Describe possible dust control measures that could be applied to significant off-lake sources, with consideration of feasibility.

- If appropriate, discuss the applicability of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Exceptional Events Policy for excluding air quality monitoring data affected by dust emissions from off-lake sources from use in determinations of whether the OVPA was in compliance with the NAAQS.

off-lake sources and recommendations for how to advance this research. Chapter 5 discusses the applicability of the Exceptional Events Rule to exceedances from off-lake sources, and Chapter 6 is a solution-focused exploration of potential dust control options that could be applied, if deemed necessary.

TABLE 1-1 The Off-Lake Source Categories Relevant to this Task

| PM10 Source Categories | Details | Comments | Relationship to Task | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off-Lake | Local (within the OVPA) | Local off-lake sources | Sources of dust emissions above 3,600 ft, adjacent or near Owens Lake, primarily located within 2–3 km of the shoreline. | The District has identified that areas adjacent to Owens Lake are causing and/or significantly contributing to PM10 exceedances. These sources include local dunes, sand sheets, flash flood deposits, and other open areas. | These are the focus of the District’s request to OLSAP. |

| Permitted stationary sources | Local sources of air pollution permitted by the District (e.g., mines, engines, landfills). | District has permits and enforcement for these sources. | These are not the focus of the District’s request to the OLSAP. However, the emissions of these sources may be relevant to the discussion. | ||

| “Other” local sources | This a large group of sources grouped together here for efficiency. Woodburning devices (fireplaces and stoves), transportation, unpaved roads, paved road dust, tailpipe emissions, prescribed and agricultural burning. | These are local sources that exist but have not been identified by the District as causing or significantly contributing to PM10 exceedances in the OVPA. | These are not the focus of the District’s request, but discussion of these events may be relevant to the discussion to establish they are not contributing significantly to PM10 emissions. | ||

| Regional (outside the OVPA) | Regional dust events | Dust events from outside the OVPA. | These events are typically mixed-source events, with additional contributions from local sources. | These are not the primary focus of the District’s request, but discussion of these events, the sources, and the PM10 contributions to monitors in the OVPA are relevant to the discussion. | |

| Wildfire smoke events | Smoke from wildfire events. | Typically regional but could be caused from a local wildfire within the OVPA. Also, as has happened in rare occasions, event could be on-lake if it occurs below 3,600 ft. | These are not the focus of the District’s request to the OLSAP. | ||

NOTES: Some PM10 exceedances are caused by primarily one of the above categories; others may be caused by any number of combinations of the above sources.

SOURCE: Phillip Kidoo, GBUAPCD, personal communication, May 9, 2024.