A Long COVID Definition: A Chronic, Systemic Disease State with Profound Consequences (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Since the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, millions of individuals across the globe have experienced ongoing symptoms following infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The long-term health effects of COVID-19, known as Long COVID, are profound. This complex and lingering medical condition has exposed shortcomings in public health messaging and education, clinical care, research, and social support services. It has also illustrated the need to better understand infection-associated chronic conditions (IACCs) more broadly, both to improve care for those who currently live with IACCs and to prepare for and respond to future pandemics (Al-Aly and Topol, 2024; CDC Foundation, 2024). Research results and available information on Long COVID have varied, in part because of the heterogeneous definitions used in research and clinical practice. A uniform, core definition could help patients, clinicians, public health practitioners, researchers, and policy makers understand and navigate Long COVID more effectively.

PREVALENCE OF LONG COVID GLOBALLY AND IN THE UNITED STATES

Long COVID is a serious global issue with medical, social, and economic impacts. Prevalence estimates vary widely. One reason for this variation is the absence of a clear-cut diagnostic biomarker or other definitive diagnostic criterion that would distinguish those with Long COVID from those whose condition is due to other reasons. In the wake of the pandemic,

Long COVID has likely been underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed (Walker et al. 2021), with Long COVID patients reporting not being believed in clinical settings (Ireson et al. 2022). Variation in prevalence estimates is compounded by the absence of a consistent definition for Long COVID and variety of terminologies to label the medical condition. Estimates of prevalence depend on how Long COVID is defined in terms of presence, timing, severity of symptoms, laboratory and imaging results, documentation of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, and background frequency of common symptoms, among other factors (O’Mahoney et al., 2023; Pagen et al., 2023; Woodrow et al., 2023).

Estimates of the percentage of those infected with SARS-CoV-2 who develop Long COVID range from 10 to 35 percent or higher (Huerne et al., 2023; Pavli et al., 2021). Based on a prevalence of 10 percent of those infected, Davis and colleagues conservatively estimate that at least 65 million people worldwide have experienced Long COVID (Davis et al., 2023). A U.S. Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics Household Pulse Survey showed, as of March 5 to April 1, 2024, about 17.6 percent of all U.S. adults have “ever experienced with Long COVID” and 6.9 percent of all U.S. adults are “currently experiencing Long COVID” (CDC, 2024). The Pulse Survey defined Long COVID as “any symptoms lasting 3 months or longer that [they] did not have prior to having coronavirus or COVID-19” (CDC, 2024a).1 Another recent publication in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report reported that the prevalence of Long COVID varied among the states and territories, ranging from 1.9 percent in the Virgin Islands to 10.6 percent in West Virginia (Ford et al., 2024).

In the United States, according to death certificate data in the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), Long COVID (or related terms) was an “underlying or contributing cause” of 3,544 deaths between January 2020 and June 2022 (Ahmad et al., 2022). With the addition of preliminary data from 2023, estimates now suggest over 5,000 deaths have been attributed to Long COVID since the start of the pandemic (Rapaport, 2024).2 The age-adjusted death rate was higher among men (7.3 per million) than women (5.5 per million), higher among those 85 years and older (117.1 per million) than among younger age groups, and higher among American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) people (14.8 per million) than among other racial and ethnic groups (Ahmad et al., 2022). Long COVID as an underlying or contributing cause of death is likely to be underestimated in the references

___________________

1 Limitations of the Household Pulse Survey: only accounted for people 18 and above, based on self-report, only counts COVID-19 cases if participant received a positive test or was told by a health care provider that they had COVID-19, and does not include people who have a worsening of existing conditions following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

2 These sentences were modified after release of the prepublication version of the report to be more consistent with the cited references.

studies as an ICD-10 code did not exist earlier in the pandemic and it has been underused (Wander et al., 2023).

NEED FOR A CLEAR DEFINITION

Defining Long COVID is challenging because of the heterogeneous nature of long-term sequelae of COVID-19, which include a wide array of symptoms and conditions with potentially variable etiologies and potential overlap with other causes (Hayes et al., 2021; Malone et al., 2022). Adding to the challenge, the clinical and scientific understanding of Long COVID is evolving as new evidence emerges on the presentations, durations, and pathogenesis of Long COVID and on its relationships to other conditions.

The complexities of Long COVID and the methodologic problems associated with studying Long COVID indicate the need for a comprehensive approach to evaluating and defining this disease state. Despite Long COVID’s relatively recent emergence, numerous definitions and descriptions of Long COVID have already been published (Box 1). However, a review of 295 research studies on Long COVID, all published before October 26, 2022, found high heterogeneity in existing definitions; this heterogeneity limits opportunities to compare interventions and accumulate evidence on Long COVID (Chaichana et al., 2023). Currently, the field does not conform to a single definition of Long COVID and does not evaluate the disease state in a consistent way (Rando et al., 2021).

The lack of a generally accepted and consistent definition for Long COVID presents challenges for clinical management and treatment, research, surveillance, and support services (Al-Aly et al., 2023; Saydah et al., 2022). For patients, challenges associated with the lack of a clear, consistent definition of Long COVID and the diversity of the range of clinical presentations and poor understanding of Long COVID can lead to: difficulties accessing medical care; skepticism and dismissal of patients’ experiences by medical professionals, peers (Au et al., 2022), family members, and employers; delay or denial of treatment; stigma; and difficulty obtaining support (Callard and Perego, 2021). An improved definition can help with raising awareness—according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 10,133 adults in February 2024, 22 percent of Americans say they haven’t heard of Long COVID, and 50 percent of Americans think that it is extremely or very important for researchers and clinicians to understand and treat Long COVID (Tyson and Pasquini, 2024).

In August 2022, OASH published an interim working definition for Long COVID based on collaboration among several government agencies and outside subject matter experts, including medical societies and patients

BOX 1

Selected Existing Long COVID Definitions and Descriptions

Office of Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH)

Long COVID is broadly defined as signs, symptoms, and conditions that continue or develop after initial COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 infection. The signs, symptoms, and conditions are present 4 weeks or more after the initial phase of infection; may be multisystemic; and may present with a relapsing–remitting pattern and progression or worsening over time, with the possibility of severe and life-threatening events even months or years after infection. Long COVID is not one condition. It represents many potentially overlapping entities, likely with different biological causes and different sets of risk factors and outcomes (HHS, 2022).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

CDC references the OASH Long COVID definition, but also says: Long COVID is a wide range of new, returning, or ongoing health problems that people experience after being infected with the virus that causes COVID-19. Most people with COVID-19 get better within a few days to a few weeks after infection, so at least 4 weeks after infection is the start of when Long COVID could first be identified. Anyone who was infected can experience Long COVID. Most people with Long COVID experienced symptoms days after first learning they had COVID-19, but some people who later experienced Long COVID did not know when they got infected (CDC, 2023b). (Note that this is not a formal definition but rather a description on the CDC website.)

National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Recovery from infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, can vary from person to person. Most patients seem to recover quickly and completely, while others report symptoms that persist for weeks or even months after the acute phase of illness has passed (a condition often referred to as “Long COVID”). In other cases, new symptoms and findings emerge after the acute infection, including when the acute phase was asymptomatic. Collectively, these long-term effects of the virus are called post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) (NIH, 2024). (Note that this is not a formal definition but rather a description on the NIH RECOVER website.)

World Health Organization (WHO)—Adults

Post-COVID-19 condition occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset, with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Common symptoms include, but are not limited to, fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction and generally have an impact on everyday functioning. Symptoms might be new onset following initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or persist from the initial illness. Symptoms might also fluctuate or relapse over time (Soriano et al., 2022).

World Health Organization (WHO)—Pediatrics

Post COVID-19 condition in children and adolescents occurs in individuals with a history of confirmed or probable SARS-CoV-2 infection, when experiencing symptoms lasting at least 2 months which initially occurred within 3 months of acute COVID-19. Current evidence suggests that symptoms more frequently reported in children and adolescents with post-COVID-19 condition compared with controls are fatigue, altered smell (anosmia), and anxiety. Other symptoms have also been reported. Symptoms generally have an impact on everyday functioning such as changes in eating habits, physical activity, behavior, academic performance, social functions (interactions with friends, peers, family) and developmental milestones. Symptoms may be new onset following initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or persist from the initial illness. They may also fluctuate or relapse over time. Workup may reveal additional diagnoses, but this does not exclude the diagnosis of post COVID-19 condition (WHO, 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), and Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP)

Ongoing symptomatic COVID-19: Signs and symptoms of COVID-19 from 4 weeks up to 12 weeks. Post-COVID-19 syndrome: Signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19 continue for more than 12 weeks and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis. It usually presents with clusters of symptoms, often overlapping, which can fluctuate and change over time and can affect any system in the body. Post-COVID-19 syndrome may be considered before 12 weeks while the possibility of an alternative underlying disease is also being assessed. In addition to the clinical case definitions, the term “long COVID” is commonly used to describe signs and symptoms that continue or develop after acute COVID-19. It includes both ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 (from 4 to 12 weeks) and post-COVID-19 syndrome (12 weeks or more) (NICE et al., 2022).

Global List of Long COVID Definitions

In addition to the above definitions, many organizations and governments across the globe have developed definitions for Long COVID and related terms. In March 2023, a list of Long COVID definitions was crowdsourced from members of the EpiCore network around the world (EpiCore, 2023).

Reimbursement Codes

In addition to Long COVID definitions, reimbursement codes have been developed. In the United States, ICD-10 code U09.9 designates “post-COVID-19 condition, unspecified” and became available in October 2021 (Pfaff et al., 2023). In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) has developed codes that align with the NICE/SIGN/RCGP definition (NICE et al., 2022)

(HHS, 2022). Other major health organizations in the United States and internationally have also published various definitions of Long COVID and related terms, and these can be useful starting points (Box 1). Furthermore, several journal articles have proposed different ways in which Long COVID could be defined (Alwan and Johnson, 2021; Baig, 2021; Chaichana et al., 2023; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, 2022; Fernandez-de-Las-Peñas et al., 2021a; Haslam et al., 2023; Lippi et al., 2023; Monika et al., 2023; Pan and Pareek, 2023; Rando et al., 2021; Raveendran, 2021). In developing its definition, the committee took advantage of these existing definitions by reviewing definitions in the context of the literature and available data and then adopting elements where appropriate.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

Recognizing the desirability of broad input and careful consideration of an improved definition, the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH) asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Standing Committee on Emerging Infectious Diseases and 21st Century Health Threats3 (standing committee) to take up the issue of defining Long COVID. To accomplish this complex task (see Box 2), a separate expert committee, the Committee on Examining the Working Definition of Long COVID (committee), was established. Members and their backgrounds are described in Appendix C.

STUDY APPROACH

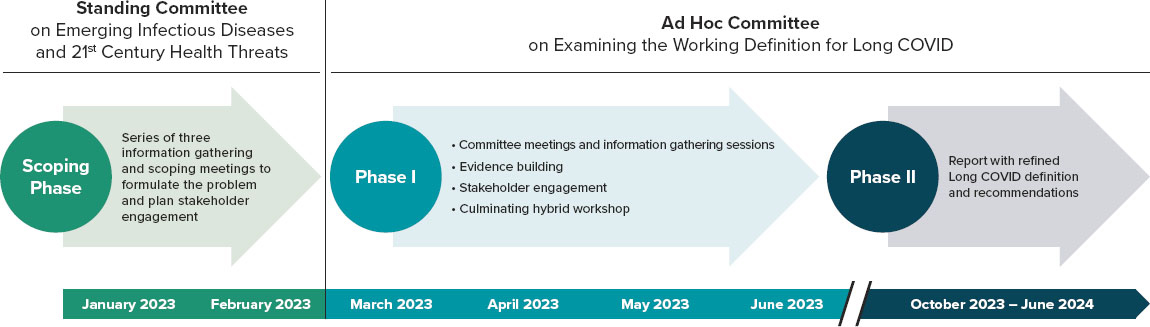

The committee’s charge was to recommend a new definition for Long COVID. To this end, the committee employed a systematic approach implemented through a multi-phase process (see Figure 1). Appendix A provides a detailed methodology of the committee’s approach, including details on the engagement process, evidence review, and public meetings.

In the 2-month scoping phase, the standing committee held three information-gathering meetings to discuss the key issues and identify the areas of expertise and stakeholders to engage in this effort.

In Phase I, the committee, along with National Academies staff and a team of consultants, engaged patients and individuals across multiple sectors to solicit input from a wide range of interested and affected parties through a series of focus group discussions and an online questionnaire;

___________________

3 To learn more about the Standing Committee on Emerging Infectious Diseases and 21st Century Health Threats, please visit https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/standing-committee-on-emerging-infectious-diseases-and-21st-century-health-threats.

BOX 2

Statement of Task

A National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee will conduct a series of public workshops to examine the current U.S. government (USG) working definition for Long COVID and related technical terms. The workshop series will consist of several sessions designed to:

- Explore literature on definitions for Long COVID in the United States, including but not limited to, definitions that are currently used for clinical care, research, surveillance, and health communication;

- Learn about challenges and barriers due to currently available definitions for Long COVID; and

- Seek input from various stakeholder groups relating to refinement, dissemination, and implementation of a definition for Long COVID.

The workshop series will conclude with a 2-day workshop discussing potential considerations for refined Long COVID definitions, terminology, and harmonizing efforts for patient engagement, clinical care, research, surveillance, across USG and relevant stakeholders. The committee will define the specific topics to be addressed, develop the workshop agendas, and select and invite speakers and other participants.

Building on the workshop series, the committee will integrate and synthesize information from the stakeholder engagement and information gathering and produce a letter report that will:

- Review additional evidence for definitions of Long COVID;

- Consider efforts that have already been completed on this topic area;

- Recommend new definitions for Long COVID and related technical terms, with descriptions of the circumstances under which these new definitions and terminology should be adopted.

The committee will make recommendations to establish considerations for maintaining an up-to-date definition for Long COVID and related technical terms.

both activities were offered in English and Spanish. More than 1,300 people participated in these activities, including patients and caregivers, public health and health care professionals, researchers, policy and advocacy professionals, payors, health care business professionals, and members of the public. One consistent theme throughout the engagement process was that the National Academies committee should listen and learn from those with lived experiences of Long COVID, including patients and their families and caregivers, and those who diagnose, treat, and study Long COVID. For example, one participant said, “Listen to the people who have been experiencing the disease, but also to people who will need to use the definition in their work.”

Details on who participated in these activities (demographics and sector/group affiliation) and the key findings are published in a publicly available report titled What We Heard: Engagement Report on the Working Definition for Long COVID.4 Engagement activities were publicly promoted through various mechanisms and networks, and the committee made focused efforts to identify an equitable list of participants that covered the full spectrum of impacted and interested people, geographies, and demographics. Demographic data was only formally collected for questionnaire respondents, and of those respondents who answered the demographic questions, they were overwhelmingly white, female, highly educated, living in urban or mostly urban areas of the United States, and had a total household income of at least $100,000. The committee notes this limited presence of underrepresented groups in its engagement efforts and emphasizes the importance of attention to recruitment methods and broader access in future efforts.

During Phase I, the committee also organized three information-gathering virtual meetings, created an online public portal to receive public comments, and held a 2-day hybrid symposium to review and discuss input gathered. Recognizing the limited presence of underrepresented groups in its structured engagement efforts, the committee made a special effort, including direct outreach to organizations that serve underrepresented populations, to engage with these groups in its information-gathering meetings and symposium.

In Phase II, the committee undertook activities to further build, prioritize, and synthesize the evidence to help inform development of the refined definition. A scoping review consisting of 116 reviews pertinent to the diagnosis of Long COVID was carried out along with an examination of

___________________

4 Available on the study webpage https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/examining-the-working-definition-for-long-covid (accessed March 11, 2024).

the primary literature. The committee also held four additional committee meetings, three in closed session and one public meeting.

The committee developed its definition based on the best evidence to date and all of the above-listed sources of information. While responsive to outside needs, concerns, and preferences, the committee recognized that different groups have varied desires and interests and examined ideas and suggestions in the context of the available scientific evidence.

Stakeholders in the Long COVID Community and Report Audiences

As mentioned previously, central to the committee’s approach was soliciting input from a wide range of sources and groups in developing the refined definition. The audience for this report includes federal agencies such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) agencies and offices, National Institute of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the U.S. Department of Social Security Administration (SSA); Long COVID patients, organizations, and groups; medical institutions and health care providers; public health agencies and practitioners; academic institutions, researchers, and educators; payers and health care business professionals; employers and human resource professionals; and international agencies. This report includes guidance for clinicians, researchers, and public health practitioners in applying the proposed definition. The committee hopes this refined definition will prove useful to ongoing federal programs and initiatives on Long COVID (see Figure 2).

Study Scope

As specified in the statement of task for this study (see Box 2), the committee was asked to develop a definition for Long COVID. The committee recognizes the many conditions that are infection-associated in addition to Long COVID, but the committee was not asked to define or address the challenges in identifying, researching, or treating these other conditions.

The committee worked to identify the best available evidence and information to refine the definition for Long COVID. The report offers a framework for applying the definition in specific use cases, including for clinical care, research, and public health, recognizing that it may be advantageous to apply additional criteria to identify a subpopulation within the definition who are best suited to the particular purpose.

A Note on Terminology

Using consistent terminology is as important as using a consistent definition. In medicine, the word “illness” often refers to the “innately

human experience of symptoms and suffering,” while the term “disease” often refers to an “alteration in biological structure or functioning” (Kleinman, 1988). To stress the systemic reality of Long COVID, while acknowledging uncertainty about etiology, this report adopts the term “disease state” when referring to Long COVID.

The words “illness” and “medical condition” both refer to an unhealthy state. To some, the word “illness” may connote a more established and serious experience of ill health. To others, including many experiencing Long COVID, “condition” or “medical condition” connotes a more lasting and serious unhealthy state. In addition to using “disease state” when referring to Long COVID, the committee uses the terms “condition,” “medical condition,” or “chronic condition.” Similarly, when referring to the unhealthy state related to any prior infection, the committee uses the term “infection-associated chronic condition.”

The term “infection-associated chronic condition” (IACC) applies to a

variety of chronic conditions that can be triggered by viruses, bacteria, fungi, or parasites (CDC Foundation, 2024). While this term may be somewhat new, the conditions are not. Millions of Americans were living with IACCs prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Use of this term highlights the ongoing nature of the medical condition and its association with a triggering infection without conveying any unwarranted conclusions about pathobiological mechanisms. Furthermore, the use of this collective term can promote alignment across diverse disease groups and patient organizations—allowing for the identification of common objectives, challenges, opportunities, and actionable steps.

IACCs include conditions triggered by infections such as Epstein-Barr, influenza, chikungunya, West Nile, Ebola, SARS, HIV, HPV, and MERS viruses (Choutka et al., 2022; Rando et al., 2021; Vivaldi et al., 2023). Conditions with a proposed non-viral infectious trigger include Q fever fatigue syndrome, tick- and vector-borne IACCs such as Lyme-associated chronic illnesses, and multiple chronic symptoms following Giardia infection (Choutka et al., 2022). Although there are variations linked to the particular infectious agent, many of these conditions share common symptoms such as fatigue, exertion intolerance, cognitive impairment, musculoskeletal pain, dysautonomia, and sleep problems, which can appear in a relapsing/remitting pattern and can resemble or overlap with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) (Choutka et al., 2022). Other researchers are considering possible similarities with chronic inflammation and immune activation seen in people living with HIV, where the persistence of the virus or viral components may be a contributing factor (Bonilla et al., 2023). Recognizing Long COVID as one of a group of IACCs could potentially facilitate research and the development of clinical indicators for better diagnosis (Kim et al., 2023). None of the pre-existing definitions the committee reviewed mention IACCs.

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, various terms have also been applied to what this report terms “Long COVID.” These include “long-haul COVID,” “post-COVID conditions,” “post-COVID syndrome,” “postacute COVID-19 syndrome,” “chronic COVID,” and “post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC).” All these terms pertain to the same broad clinical condition (Turner et al., 2023). The committee intentionally adopted the patient-developed term, “Long COVID,” because its simplicity and familiarity can facilitate communication within and between the scientific community and the public. One participant said, “Patients need to be able to understand it and see themselves in the definition, because they may need to advocate for themselves or their loved ones for initial care (or continued care or recognition).”

The use of the term “Long COVID” is also consistent with WHO

recommendations to adopt unbiased, neutral, non-stigmatizing descriptive terms when cause, mechanism, and pathology of a new condition have not yet been established (WHO, 2015). While similarly neutral, the term PASC can imply a sharper virologic or symptomatic differentiation between “acute” and “post-acute” stages than is often the case (Munblit et al., 2022).

Report Structure

The report is organized to reflect the study’s approach and key priority areas for refining and implementing the working definition of Long COVID, as identified by the committee and statement of task. The report contains seven sections, the first of which is the above introduction and discussion of the background for the study (1). This is followed by a section and figure outlining the refined definition developed by the committee (2). The definition has a core component in bold font, plus a set of illustrative symptoms and diagnosable conditions, followed by seven important features that elaborate on the core component. The next section summarizes evidence supporting key elements and features of the definition (3), including such aspects as balancing errors of inclusion and exclusion, attribution to infection, onset and duration, symptoms and clinical expression, functional impact, considerations of equity, alternative diagnoses, biomarkers, and risk factors. The implementation use-cases section (4) outlines frameworks for applying the definition for multiple purposes, specifically clinical care, research, and public health surveillance applications. This is followed by a section discussing the need and parameters for updating the definition as evidence accumulates and understanding evolves (5). This section also identifies priority areas for future research to improve the definition. The report goes on to describe key limitations, prominently including limitations imposed by the available knowledge about and understanding of Long COVID (6). The final section (7) includes the committee’s concluding remarks and three recommendations.

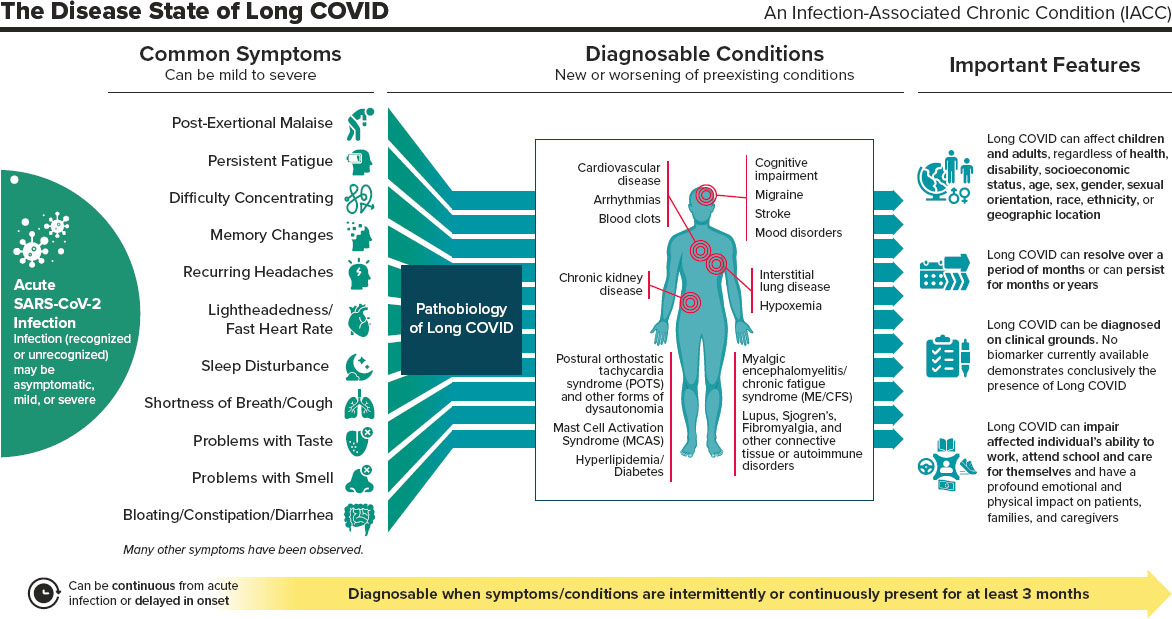

2024 NASEM LONG COVID DEFINITION

Long COVID (LC) is an infection-associated chronic condition (IACC) that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.

LC manifests in multiple ways. A complete enumeration of possible signs, symptoms, and diagnosable conditions of LC would have hundreds of entries. Any organ system can be involved, and LC patients can present with

- single or multiple symptoms, such as shortness of breath, cough, persistent fatigue, post-exertional malaise, difficulty concentrating, memory changes, recurring headache, lightheadedness, fast heart rate, sleep disturbance, problems with taste or smell, bloating, constipation, and diarrhea.

- single or multiple diagnosable conditions, such as interstitial lung disease and hypoxemia, cardiovascular disease and arrhythmias, cognitive impairment, mood disorders, anxiety, migraine, stroke, blood clots, chronic kidney disease, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other forms of dysautonomia, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), fibromyalgia, connective tissue disorders, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjogren’s syndrome.

Important Features of LC:

- LC can follow asymptomatic, mild, or severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Previous infections may have been recognized or unrecognized.

- LC can be continuous from the time of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection or can be delayed in onset for weeks or months following what had appeared to be full recovery from acute infection.

- LC can affect children and adults, regardless of health, disability, or socioeconomic status, age, sex, gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, or geographic location.

- LC can exacerbate pre-existing health conditions or present as new conditions.

- LC can range from mild to severe. It can resolve over a period of months or can persist for months or years.

- LC can be diagnosed on clinical grounds. No biomarker currently available demonstrates conclusively the presence of LC.

- LC can impair individuals’ ability to work, attend school, take care of family, and care for themselves. It can have a profound emotional and physical impact on patients and their families and caregivers.

This page intentionally left blank.