Artificial Intelligence in Health Professions Education: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction1

The Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education held a multi-day workshop series on Artificial Intelligence in Health Professions Education. The workshop was held both virtually and in-person and took place over 4 non-consecutive days. The first session, held on March 3, 2023, served to provide a background on artificial intelligence (AI) and its role in health professions education and practice. The second session, held on March 15, 2023, explored the social, cultural, policy, legal, and regulatory considerations of integrating AI into health care, and the third session, held on March 16, 2023, examined the competencies health professionals need to effectively and comfortably use AI in practice. Finally, a closing session was held on April 26, 2023, devoted to discussing steps for integrating AI into health professions education using real-world examples. This workshop proceedings generally follows the order in which the sessions occurred.

The full workshop agenda is provided in Appendix B, and a list of reading materials from the workshop is provided in Appendix D. Biographies of the speakers can be found in Appendix C, while a listing of the members of the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education, which hosted the workshop, are in Appendix A. The workshop was planned by

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop has been prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

a committee of experts (Appendix C) in accordance with the Statement of Task (Box 1-1). A glossary of terms can be found in Appendix E.

THE ROLE OF AI ACROSS HEALTH PROFESSIONS

The workshop series began with a pre-workshop virtual session held on March 3, 2023. Carole Tucker, the associate dean of research at the University of Texas Medical Branch, welcomed participants to the session, saying that there were two goals of this session: first, to better understand what AI is and, second, to explore why it is necessary for health professionals and educators to recognize the potential role of AI. Saying that the first would be addressed by the keynote speaker, Tucker addressed the second by saying that AI is “already here and it is here to stay.” Given that AI is already

embedded in everyday life, it is important for those in the health professions to understand how AI is being used and may be used within and outside of health care, which in turn will have benefits for both health professions education and practice. Tucker then highlighted an aspect of the day’s session featuring speakers describing their experiences with AI in health care. She explained that the intent behind sharing practice-based experiences was to stimulate thinking and discussion among educators about what is needed in health professions education to prepare learners so that they are ready to use AI when they shift from classroom learning to the clinical learning environment. These practice-based presentations were elaborated on by formal comments offered by two students. The invited students, who were enrolled in medical and nursing schools, shared their perspectives on AI in health professions education. Reflections from both the learners—Mollie Hobensack, a Ph.D. candidate at the Columbia University School of Nursing, and Areeba Abid, an M.D./Ph.D. candidate at the Emory University School of Medicine—are summarized in boxes following each presentation (see Boxes 1-2, 1-3, 1-4, and 1-5). Virtual and in-person participants listened to the presentations and discussions exploring read-ahead materials that were embedded in the workshop agenda found in Appendix B. Tucker introduced the keynote speaker, Cornelius James, clinical assistant professor at the University of Michigan Medical School, who underscored the speed at which the field of AI is changing, before walking the audience through a hypothetical scenario involving AI.

A Hypothetical AI Scenario

James began with a brief hypothetical scenario. He asked workshop participants to imagine they are caring for a 73-year-old man named Mr. Harris, with a recent diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mr. Harris presents to the office for a routine check-up and is accompanied by his son Adam. Adam expresses concern about his father’s risk of falling, but Mr. Harris insists that a recent fall was merely due to old shoes or walking too fast. After some discussion, Mr. Harris agrees to activate an AI-based application that uses sensors embedded in a smartwatch to assess the risk of falling. Over the course of a month, the monitoring reveals multiple loss of balance events, and the algorithm identifies Mr. Harris as high risk for falling. James asked workshop participants to consider how their care of Mr. Harris might be affected by this information.

Applications such as this are possible due to the ubiquity and growth of big data and AI, James said. Devices such as smartphones, cars, appliances, and watches produce large amounts of data, and computers are capable of quickly processing and interpreting these data. For example, email providers use machine learning (ML) methods to categorize spam mail, and

streaming services use viewing history to provide recommendations about shows that may be of interest. AI is an umbrella term that means the use of computers to perform tasks that typically require objective reasoning and understanding, James said. There are multiple domains within AI, including natural language processing (e.g., Alexa, ChatGPT [Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer]), and computer vision. Another major domain of AI is ML, defined as the “use of statistical and mathematical modeling techniques that use a variety of approaches to automatically learn and improve the prediction of a target state without explicit programming” (Matheny et al., 2019). A technique within ML is called deep learning, in which artificial neural networks are used to solve complex clinical problems. Deep learning models, James said, have many layers of information and connections of artificial neurons that are drawn between features at each level of the model. While these tools can be useful in making sense of complex information, there are concerns about not being able to know exactly what led to a model’s prediction—in other words, not being able to see inside the “black box.” This is a particular concern, James said, when deep learning is used to make decisions about the care of patients, as clinicians often want to know the reasons for a recommendation.

There has been a “data explosion” in health care in recent years and, along with it, a proliferation of AI and ML intended for use in a health care setting. The amount of health-related data will only continue to increase, James said, especially as more patients adopt wearable devices. With the amount of data increasing exponentially, the number of facts affecting patient care decisions will exceed human cognitive capacity. AI applications offer an approach for managing these data and helping patients and providers make decisions. While the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved more than 500 AI-based health care devices and algorithms, the use of AI in health care has lagged behind other fields.

James identified a number of challenges to the implementation of AI in health care:

- The potential for bias and perpetuation of inequalities and disparities;

- Issues around governance and regulation;

- The trust of providers and patients;

- Transparency and data sharing;

- Dataset quality and availability;

- Integration of AI into the infrastructure, process, and workflow of health care; and

- Calibration drift.

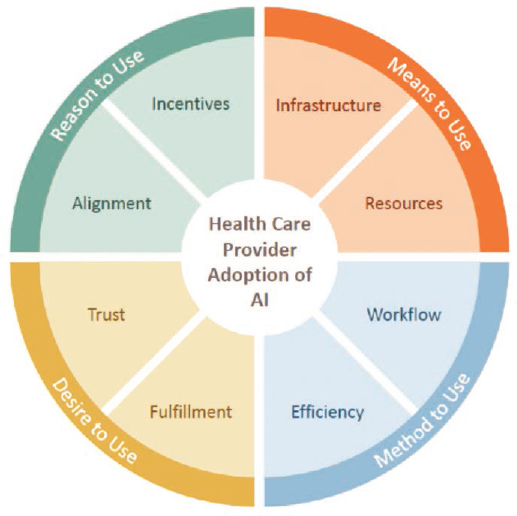

These challenges, James said, can be grouped into four overarching categories related to the adoption of technology by health care providers

SOURCE: Presented by Cornelius James, March 3, 2023 (Adler-Milstein et al., 2022).

(Figure 1-1): challenges related to the reasons a provider would choose to use AI, to the means a provider has to use AI, to the method used for AI, and to the desire to use AI.

Impact on Health Professions Education

The deluge of data and the use of AI in health care has and will continue to affect health professions education, James said. The traditional model for educating health care professionals has been the biomedical model, but the proliferation of AI-based technologies calls for a shift to a “biotechnomedical” model of education. This new model, he said, would go beyond the human biological system of simply understanding normal and abnormal function. A biotechnomedical model could use data-generated AI for proposing interventions in human disease and, as such, could expand the potential impacts of intelligent technologies in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease. Currently, AI has a minimal presence in medical education curriculum, and it is primarily found in non-mandatory offerings such as electives, workshops, and certificate programs. James argued that this is insufficient for preparing health care professionals to effectively

engage with AI; he expects that AI will become firmly integrated or embedded into curricula over the next few years.

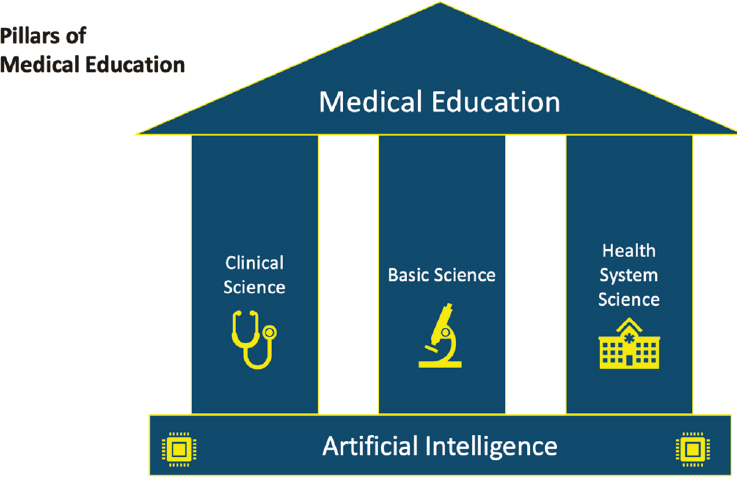

The three pillars of medical education are clinical science, basic science, and health system science; James predicted that within 10 years AI will become a foundation for these pillars, and it will transform the way educators and clinicians teach, assess, and apply information in these domains (Figure 1-2). This will require rethinking and reconsidering which tasks will be delegated to clinicians and what tasks will be delegated to AI. AI is a “fundamental tool of medicine,” James said, and clinicians of the future will need to have the ability to interact, engage, and work with this tool.

James told workshop participants about his work to develop curricula to teach learners across the continuum of medical education about AI. The mission of the Data Augmented, Technology Assisted Medical Decision Making (DATA-MD) team is “to develop, implement, and disseminate innovative health care AI/ML curricula that serve as a foundation for medical educators to develop curricula specific to their own institutions and/or specialties.” The team includes people from a variety of perspectives and backgrounds, including clinicians, data scientists, lawyers, researchers, medical educators, and administrators. They are developing an online curriculum and are working with the Center for Academic Innovation at the University of Michigan to ensure its launch in August 2023. The curriculum contains four modules:

SOURCE: Presented by Cornelius James, March 3, 2023 (Fred and Gonzalo, 2018).

- Introduction to AI/ML in Healthcare

- Foundational Biostats and Epidemiology in AI/ML for Health Professionals

- Using AI/ML to Augment Diagnostic Decisions

- Ethical and Legal Use of AI/ML in the Diagnostic Process

Another web-based curriculum, which takes a closer look at the issues surrounding AI/ML, will launch in late 2023. It contains seven modules:

- Intro to AI

- Methodologies

- Diagnosis

- Treatment and Prognosis

- Law, Ethics, Regulation

- AI in the Health System

- Precision Medicine

Both curricula will be evaluated for effectiveness in teaching learners, James said.

James closed by saying that AI has the potential to transform the delivery of health care, but AI/ML instruction in health professions education is lacking. There is a need to consider how to incorporate this content into curricula, and health professionals must be vocal stakeholders in the development, deployment, and education when it comes to use of AI- and ML-based technologies in health care.

AI in the Data-to-Knowledge Transformation

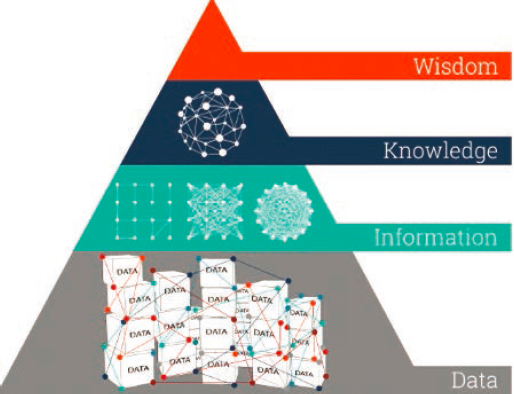

Tucker said that she takes an information science approach to AI. Through this lens, data are transformed into information through a variety of processes. Out of the information comes knowledge, and out of knowledge comes wisdom (Figure 1-3). AI can provide information and thus knowledge by finding patterns in data, Tucker said. There has been an explosion of data and also of sources of data, from payers to governments to wearable devices. However, data by themselves are just data, she said. What is needed is information and knowledge, which require finding patterns in the data and being able to contextualize and understand these patterns.

Although there are fears surrounding big data and AI, big data and AI are neither the problem nor the answer, Tucker said. She explained how the information and knowledge generated by AI build on prior data, with all their limitations and biases. For example, she said, large health care datasets are generally focused on aspects of health care that are disease promoting (e.g., data from electronic health records). It may be challenging to use these data to look for salutogenic aspects of health. New sources of data, such as wearable sensors, may provide information on a more balanced notion of health, Tucker said.

The transformation of data into information and knowledge requires theoretical framings to make sense of the data. AI is not neutral but is

SOURCE: Presented by Carole Tucker, March 3, 2023; graphic created by Ontotext. 2022. “What is the Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom (DIKW) Pyramid?” https://www.ontotext.com/knowledgehub/fundamentals/dikw-pyramid.

driven by theoretical frameworks and analytical techniques; for example, is the AI designed to look for connections and similarities, or to look for statistical differences? It is important to know what is in the “black box” to understand how the data are being transformed into information, Tucker said. It has been said that generative AI is not simply a technology or tool but reflects the developer and the developer’s motivation. Tucker commented that health professions learners and practitioners need to be not just passive learners about AI but active participants in guiding the use of AI within policies and systems.

Tucker shared additional resources for those interested in learning more:

- Bridge to AI (https://bridge2ai.org/)

- Big Data to Knowledge (https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ep/BD2KGrants.html)

- American Medical Informatics Association (https://amia.org/)

Interoperability for Effective AI

Interoperability must be considered as the first step for an inclusive, holistic approach in improving patient safety, care quality, and care delivery outcomes while reducing clinician burden and waste, said Kelly Aldrich, an informatics nurse specialist at Vanderbilt University. The definition of interoperability depends on the lens the person is looking through, she said. The Center for Medical Interoperability (2021) defines it as “the ability of

information to be shared and used seamlessly across medical devices and systems to improve health and care coordination.” The 21st Century Cures Act describes interoperability as “health IT [information technology] that enables the secure exchange of electronic health information with, and use of electronic health information from, other health IT without special effort on the part of the user; [and] allows for complete access, exchange, and use of all electronically accessible health information for authorized use under applicable State or Federal law” (ONC and HHS, 2020). Aldrich said that, in comparison, clinicians would be likely to define interoperability as a “plug and play” system for health care; Aldrich compared this system to LEGOs, in which any piece or set can be combined with other LEGOs, and “they just work” (Center for Medical Interoperability, 2021).

Like Tucker, Aldrich said that in order to be useful, data must be transformed into information, knowledge, and then wisdom. This means that AI, according to Lehne et al. (2019), is only useful if it can be converted into meaningful information, which “requires high-quality datasets, seamless communication across IT systems, and standard data formats that can be processed by humans and machines” (p. 1). Where and how are data obtained to create wisdom and to improve the patient’s outcomes and our impact on care and coordination? Doing so requires a model; Aldrich spoke about the Interoperability Maturity Model created by the Center for Medical Interoperability (2021) (Figure 1-4). To have interoperability, she emphasized the “need to make our way completely around the spoke.” Building a system with interoperability, Aldrich said, means considering the following:

- How connected, secure, and resilient is your health system’s infrastructure?

- Is the information your system needs to exchange properly formatted to meet your needs?

- Do the places that send and receive your data speak the same language?

- Is the information sequenced to meet your needs?

- Do your information exchanges enable safety and optimal decisions?

Clinicians want to see data organized and presented in a way that allows them to make decisions to best care for their patients, Aldrich said. She compared this scenario to a fighter pilot cockpit, filled with screens that display easy-to-read, timely data and buttons that allow the pilot to take action. What educators and clinicians have instead, she said, is a system with multiple screens and systems that do not all feed into the same infrastructure and do not allow the clinician easy access to the data for decision making. Many of the medical devices and systems used for patients contain

SOURCE: Presented by Kelly Aldrich, March 3, 2023 (Center for Medical Interoperability, 2021).

proprietary data and cannot “speak” to one another. The systems may be collecting useful data, but if the data are not entered into the patient’s record, they cannot be used to improve care. There are concerns with system vulnerabilities and lack of transparency; for example, there would be no way to know if a system had been hacked in a way that affected patient care. “Our patients and care teams deserve better,” she said. A lack of comprehensive interoperability and data liquidity can compromise patient safety, undermine care quality and outcomes, contribute to clinician fatigue, and waste billions of dollars each year.

Clinical interoperability cannot be an afterthought, Aldrich said; it needs to be a leading requirement in the adoption of health IT solutions. Well-functioning health systems are able to appropriately, seamlessly, and interchangeably share and use information. The safety and quality problems associated with a lack of interoperability are a systems issue, not a failure of the workforce. Clinicians are tired and need help using data to coordinate care. Aldrich quoted the report Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001), which reads as follows:

Health care has safety and quality problems because it relies on outmoded systems of work. Poor designs set the workforce up to fail, regardless of how hard they try. If we want safer, higher-quality care, we will need to have redesigned systems of care, including the use of information technology to support clinical and administrative processes. (p. 4)

In integrating AI into health care, Aldrich said, educators and clinicians should look to other fields and industries for ideas. For example, other industries use digital twins (virtual copies of physical objects) to map a system and identify positive and negative impacts; health care could do the same with the care system. Aldrich compared the air traffic control system—in which technologies present clear information to controllers in order to coordinate flights—to the patient care system, in which clinicians still routinely use white boards and markers and magnets to coordinate the care of patients.

At the Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, educators are working to “prescribe technology,” Aldrich said. For example, students use immersive virtual reality for empathy training and augmented simulation for clinical skills training. Students get experience using ambient intelligence, which uses sensors and AI to enable caregivers to provide quality care efficiently. For example, an ambient intelligence system can use data to predict if a patient is likely to get out of bed and fall before a caregiver can reach the patient.

Chatbots for Mental Health: AI in Clinical Practice

Chatbots are a software application used to conduct conversations via text or text-to-speech, said Eduardo Bunge, the associate chair of the psychology department at Palo Alto University. For example, it is now possible to chat via text with an online assistant or via voice with a personal Amazon Echo or Google Assistant. Lately, chatbots are being built with a digital persona—that is, a “person” that can be seen or heard, or both. In the field of mental health, traditional in-person talk therapy is being supplemented with different types of chatbots.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of chatbots currently available: rule-based and AI-based (and they can be combined). Rule-based chatbots are programmed to respond a specific way to keywords or questions; they cannot generate their own answers or respond to queries that are not programmed. This can be useful, Bunge said, when there is a good match between what the user needs and what the chatbot is programmed to do (e.g., discuss respiratory problems). When a query or response is outside of the chatbot’s programmed scope, the chatbot usually responds with a generic response or apology. This type of chatbot is not particularly hard to create, even for those who are not tech-savvy. The other type of chatbot is AI-based and uses natural language processing and ML. These types of chatbots, which include Amazon’s Alexa and ChatGPT, can generate their own responses and use natural language in responding. These technologies are more sophisticated and require a level of technological expertise.

There are numerous chatbot products on the market in the mental health space, Bunge said, and they are mostly rule-based chatbots. These include Woebot, Youper, Replika, Wysa, and TalkToPoppy. These types of chatbots have shown promise; for example, a meta-analysis found a moderate effect of these interventions for delivering psychotherapy to adults with depressive and anxiety symptoms (Lim et al., 2022). Bunge cautioned that the analysis looked at only a handful of studies and patient follow-up was short-term. Several other papers have reported that patients establish therapeutic bonds with chatbots, including Darcy et al. (2021), Dosovitsky and Bunge (2021), and Beatty et al. (2022).

Technologies involving chatbots and AI yield a lot of power as well as a lot of responsibility, Bunge said. Everyone in health care needs to be aware of these tools and their potential benefits, including reducing work burden, improving outcomes, and expediting processes. These benefits could be applied to both the practice of health care and the education of future health professionals. Bunge suggested that health professions students could even develop their own chatbots to better understand the technology; for example, they could make a simple rule-based chatbot to deliver psycho-education about depression or other disorders. The promise of chatbots lies in the fact that they can mimic conversations that humans have with other humans, Bunge said. Respondents tend to anthropomorphize chatbots, which leads to a higher engagement level than with other digital interventions. Through this process, people create bonds and have more natural interactions, which leads to longer and better engagement, he added.

DISCUSSION

Following the presentations and learner reflections, a panel discussion was held in which members of the planning committee (Appendix C) asked speakers questions while also sharing personal perspectives and feedback.

Relationship between Clinicians and AI

Kimberly Lomis, the vice president of undergraduate medical education innovations for the American Medical Association, moderated the discussion and asked panelists about the relational aspects of integrating AI into the clinical setting—that is, what do clinicians need to bring to the table in order to best interact with AI and achieve the optimal relationship? James responded that AI has been described as a “teammate.” A successful team has established goals, clearly defined roles, mutual trust, communication, and measurable outcomes—all of which would be important in the relationship between AI and clinicians. Another phrase that has been used for AI is “augmented intelligence.” This term emphasizes the fact that each member of the care team, from patients to clinicians to AI, brings his or her own expertise and skills and augments the expertise and skills of other members. For example, James said, AI could take certain tasks off the clinician’s plate, which would then allow the clinician to focus on fostering and strengthening the patient–clinician relationship. By transferring some tasks to AI, clinicians can “be a bit more human in their interactions with their patients.” Bunge added that people can sometimes see AI as a threat to their jobs; he suggested that AI should instead be seen as an ally that can help people do their jobs better. However, for clinicians to view AI in this way, they need to be exposed to it early and often. Students need to have experiences working with AI technologies to build a trust in AI and to know what roles and tasks are appropriate for AI.

Promising Applications for Language-Generative AI

Carl Sheperis, dean at Texas A&M University–San Antonio, said there has been an incredible evolution of language-generative AI recently (e.g., ChatGPT) and asked panelists to share their opinion about the most promising future developments in this area for health care. Aldrich said that when looking for promising AI applications, it is critical to keep focused on the problem being solved. Patient safety and quality of care have been issues for decades, and clinicians are facing moral injury as they manage care without interoperability and without technologies that can help them coordinate care. Technology can be used to build a digital twin of the current system and map out how to close the gap between the current system

and the ideal system, Aldrich said. By focusing on the problems that need to be solved, technologies can be developed and implemented to address those specific problems. Most importantly, Sheperis said, is keeping the patient at the center and identifying opportunities to use technology to improve the patient experience and care.

Restoring Joy

AI and other technologies have the potential to restore joy to the health care profession, said Lisa Howley, senior director of strategic initiatives and partnerships at the Association of American Medical Colleges. She shared a quote from Robert Wachter (2017): “The combination of intelligent algorithms and automatic data entry will allow each health care professional to practice far closer to the top of her license. As less time is wasted on documenting the care, doctors and nurses will have more direct contact with patients and families, restoring much of the joy in practice that has been eroding, like a coral reef, with each new wave of nonclinical demands” (p. 260). She asked panelists for their thoughts on how AI could be used to free up time for clinicians to spend more time at the bedside with the patient, engaging in more meaningful and joyful activities. James responded that when the electronic health record was first developed, there were significant promises that it would improve clinicians’ lives and practice. However, these promises have largely not been fulfilled, in part because clinicians were not involved in the development or deployment of the technologies. In moving forward with AI, it will be important to learn lessons from these prior experiences and to keep in mind the workflow of the clinician and what would actually be helpful. For example, there are AI technologies in development that will help clinicians with documentation and billing, so the clinician can engage more effectively with patients. Tucker noted that the electronic health record was developed without a close look at how technology could improve the process; instead, it “basically took a paper [record] and put it in a computer.”