A Review of the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives (2016)

Chapter: Appendix A: Greater Sage-Grouse: A Collaborative Conservation Effort

Appendix A

Greater Sage-Grouse: A Collaborative Conservation Effort

INTRODUCTION

The greater sage-grouse case study illustrates the importance of partnerships between private landowners and state and federal agencies; how challenging it can be for a Landscape Conservation Cooperative (LCC) to integrate into an existing landscape-scale issue; how the scale at which conservation action needs to take place can vary; and how difficult it is to attribute credit to any single entity in such a collaborative effort. The discussion below illustrates how a landscape approach can catalyze and facilitate conservation that averts the listing of a species. The narrative demonstrates the benefits of the landscape approach for addressing emerging conservation priorities and how voluntary conservation actions can help to avoid a species decline to the point where it requires listing. Maintaining healthy population levels to avoid the listing “trigger” benefits the target species but also benefits a broad range of stakeholders such as public land managers, private landowners, ranching interests, and oil, gas, and mineral developers who could potentially lose some flexibility in how they manage their resources if a species becomes listed.

Although LCCs did not play a central role in this case, they were established to identify such priority species or habitats and to facilitate collaboration to yield the type of collaborative conservation effort that is described below. It became clear when reviewing the LCC activities related to sage-grouse that LCCs joined an already very mature partnership and the LCC extent of contribution is not obvious. In almost every activity listed above, the LCC participated as a stakeholder in an initiative but seldom appeared to be the catalyst for the initiative. Notwithstanding, their funds and emphasis on landscape problems have been helpful in supporting some very important work on greater sage-grouse.

The LCCs also have contributed to the greater sage-grouse conservation effort in more subtle ways. For example, the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA), the state of Nevada, and several federal agencies combined resources to prepare a strategic approach based on resistance and resilience concepts for conservation of sagebrush ecosystems and greater sage-grouse (Chambers et al., 2014). While the direct funding for this effort came from state and federal agencies, the Great Basin LCC provided staff support for a GIS and modeling expert who played a key role in the creation of a geospatial tool required to implement the Fire and Invasive Species Team protocol described by Chambers et al. (2014).

However, it also illustrates that the LCC program has played an important role in several initiatives, especially those that span multiple jurisdictions, interactions among multiple species, and issues that play out over long timescales (i.e., those aspects that are most difficult for other agencies to address).

The sage-grouse example also highlights the fact that the existing LCC boundaries will not always match the scale of landscape-scale issues. This is not surprising as no administrative boundary will perfectly match the distribution of species or landscapes. Even the administration of the LCCs results in some difficulty in coordinating landscape-scale research for a species such as the greater sage-grouse. For example, the Inter-LCC Greater Sage-Grouse initiative was administered out of Region 6, even though the region has administrative responsibility for only two of the four LCCs containing habitat for the species. LCC boundaries may constrain conversations. Bird Conservation Regions with modifications based on terrestrial and freshwater ecoregions (Gallant, 1989; Omernik, 1995, 2004; Abell et al., 2000) are the basis for the LCC boundaries, but many of the landscape-scale issues are not captured within these boundaries.

It is important to note that this sage-grouse conservation effort was initiated long before the establishment of the LCCs. The case study intends to illustrate how voluntary conservation partnerships can avert the decline of a target species and avoid listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Keeping the greater sage-grouse off the endangered species list is beneficial not only to the survival of the spe-

SOURCE: Garton et al., 2011.

cies in question, but also to the broad range of stakeholders mentioned above. The following case study demonstrates the range of actions and partnerships that are contributing to this conservation effort.

The Target Species Range and Ecology

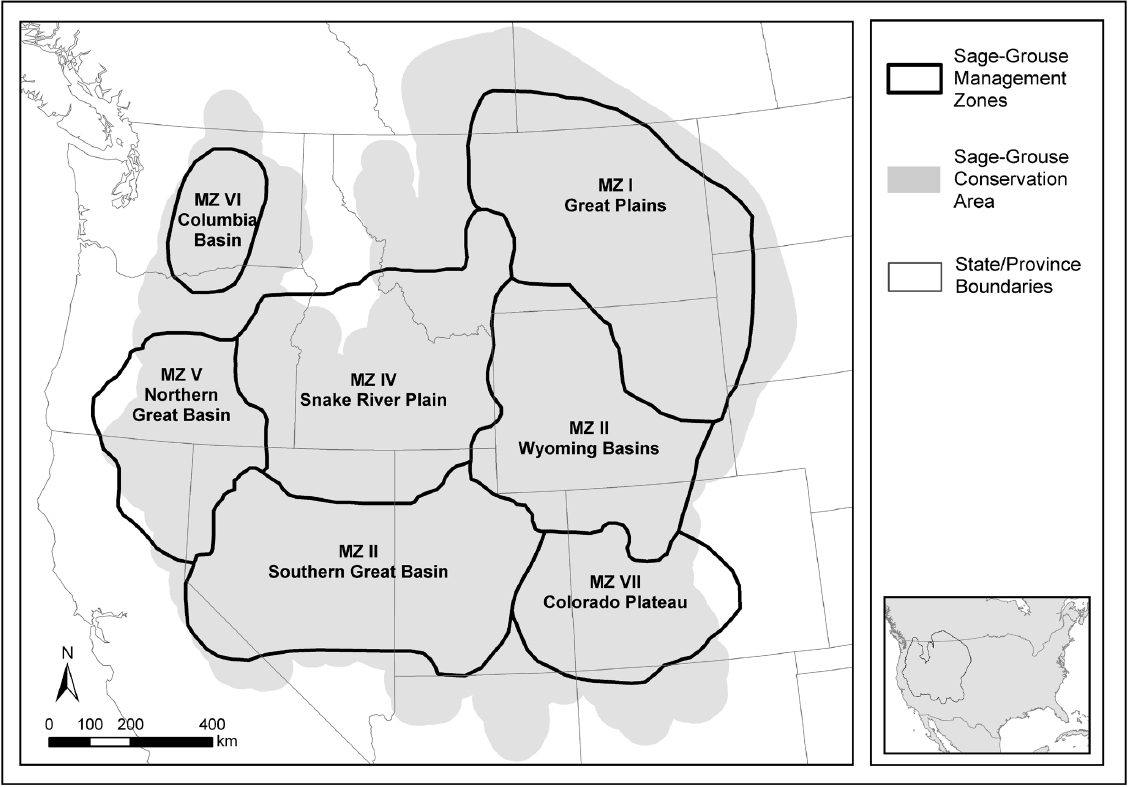

The greater sage-grouse is endemic to the sagebrush steppe landscape in 11 states in the United States and in two Canadian provinces (see Figure A.1). The greater sage-grouse is protected by state law throughout its range and managed as an upland gamebird by state wildlife agencies. The species is experiencing range-wide population declines due to agricultural development, large-scale range improvements (sagebrush control), urban and exurban development, large wildfires, invasion of exotic plants, and more recently, energy development.

Conservations Efforts Led by State Agencies

Western states have a longstanding practice for addressing population and habitat conservation across state lines through a range of cross-state partnerships. Recognizing the decline of the sage-grouse populations, members of WAFWA signed a “Memorandum of Understanding [MOU] Among Members of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies for the Conservation and Management of Sage-Grouse in North America.”1 The MOU was expanded in 2000 to include federal agencies (U.S. Forest Service [USFS], Bureau of Land Management [BLM], U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [FWS], U.S. Geological Survey [USGS], Natural Resources Conservation Service [NRCS], and Farm Service Agency).

In addition to collaborating with the FWS through federal initiatives, many of the 11 states where greater sage-grouse habitat occurs have identified important areas needing special consideration in land-use decisions. California and Nevada have been working with the BLM, USFS, NRCS, and the FWS to conserve the bi-state sage-grouse population, considered a distinct population by the FWS for more than a decade. In March 2012, the bi-state Executive Oversight

___________________

1 See http://www.wafwa.org/initiatives/sage_steppe/Sage-GrouseConservationImplementationMOU.pdf.

Committee for Conservation of Greater Sage-Grouse published the Bi-state Action Plan—Past, Present, and Future Actions for Conservation of the Greater Sage-Grouse Bi-state Distinct Population Segment (Bi-State Technical Advisory Committee Nevada and California, 2013). The action plan summarizes the steps that have been taken to conserve the bi-state population of greater sage-grouse and identified objectives and strategies guiding future conservation efforts. The states of Montana, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming have identified core habitat areas within their states that are considered essential for the maintenance of sage-grouse in those states.

In Wyoming, for example, the governor issued the Sage-Grouse Executive Order (SGEO) through the regulatory authority of state agencies and collaboration with industry, federal land management agencies, and local sage-grouse working groups. The SGEO provides for coordination of greater sage-grouse conservation efforts among all stakeholders statewide and an evaluation of projects within greater sage-grouse core areas, and prohibits state agencies in most cases from taking actions leading to the loss of core habitat.

The governor of Idaho established the Idaho Sage-Grouse Task Force in 2012 to “prevent the need for the federal protection under ESA.”2 The Task Force developed through broad stakeholder engagement an alternative management plan to listing the species under ESA.3 It identified three distinct management areas, ranging from management with a “restrictive approach” to management areas that would allow “multiuse activities.”

The Western Governors’ Association (WGA) and WAFWA play an important role in coordinating greater sage-grouse conservation initiatives among states and federal agencies. In their Sage Grouse Inventory 2014 Conservation Initiatives, the WGA summarized the activities taking place to conserve the sage-grouse in all 11 states within the species range. WAFWA focused on educating its membership about the species and different measures needed for its conservation. In their “Gap Report,” Mayer et al. (2013) recognized that wildfire and the subsequent spread of invasive plants continue to play a huge role in the loss of sagebrush steppe habitat, particularly in the western portion of the greater sage-grouse range. Their report summarized the policy, fiscal, and science challenges that land managers encounter related to the control and reduction of the “invasive plant/fire complex,” in relation to greater sage-grouse conservation. WAFWA also provides a clearinghouse for sources of information relevant to important initiatives related to greater sage-grouse and a vehicle for states and federal agencies to pool funds for large-scale projects.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Listing Process

The FWS was petitioned to list the greater sage-grouse under ESA in 2002 and again in 2003. On January 12, 2005, the agency ruled that a listing as threatened or endangered was not warranted. In 2008, the FWS announced a status review and requested new information for the species in response to new listing petitions. The FWS reached the conclusion in 2010 that listing of the greater sage-grouse was warranted due to habitat loss and fragmentation and inadequacy of regulatory mechanisms that govern habitat loss and fragmentation. The agency identified fragmentation of sagebrush landscapes as one of the primary causes of the decline of greater sage-grouse populations. The direct loss of habitat on a large scale due to invasive species following wildfires, agricultural conversion of sagebrush landscapes to grasslands, and poor grazing practices is exacerbated by displacement from otherwise suitable habitat and functional habitat loss due to energy and other infrastructure developments. Nevertheless, the FWS determined that the listing was precluded because of higher-priority listing actions. On September 30, 2015, the “U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) . . . conclude[d] that the charismatic rangeland bird does not warrant protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).”4 In this press release, the secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior credits the voluntary conservation efforts and the partnerships between federal and state agencies as well as private landowners and conservation groups for contributing to this historic decision.

Conservations Efforts Supported by Federal Agencies

In 2012, the FWS convened the Conservation Objectives Team to initiate a collaborative approach with the states to develop range-wide conservation objectives to both inform the 2015 listing decision and to provide guidance to measures being taken to conserve the greater sage-grouse by individual states and agencies. The FWS has also developed a number of partnerships throughout the 11-state region occupied by the species in an effort to accomplish as many greater sage-grouse conservation projects as possible and to ensure as much protection for their habitat as possible prior to the 2015 listing deadline.

A number of the federal partners have created Candidate Conservation Agreements (CCAs) with private landowners—CCAs with Assurances (CCAA)—for the greater sage-grouse under Section 10(a)(1)(A) of ESA.5 Both are

___________________

2 See https://fishandgame.idaho.gov/public/wildlife/?getPage=310.

3 See https://fishandgame.idaho.gov/public/wildlife/SGtaskForce/alternative.pdf.

4 See https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/historic-conservation-campaignprotects-greater-sage-grouse.

5 CCAs are formal, voluntary agreements between the FWS and one or more parties to address the conservation needs of one or more candidate species or species likely to become candidates in the near future. Participants voluntarily commit to implement specific actions designed to remove or reduce threats to the covered species, so that listing may not be necessary (http://www.fws.gov/endangered/esa-library/pdf/CCAs.pdf). Because a permit is not issued for a CCA, there are no assurances that conservation

conservation agreements between the FWS and other parties to initiate voluntary conservation actions to avoid listing of candidate species. Examples of such conservation agreements include the following:

- The BLM entered into a number of CCAs with the FWS for rangeland management in Oregon and Wyoming.

- The FWS recently announced a complementary CCAA in Oregon allowing landowners in all eight eastern and central Oregon counties with greater sage-grouse habitat to enroll in the voluntary program.

Another approach for conservation of greater sage-grouse habitat is led by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s NRCS, which created the Sage Grouse Initiative that includes the NRCS, ranchers, state and federal agencies, universities, nonprofit groups, and private businesses. In the past 5 years, the Sage Grouse Initiative has leveraged the NRCS investment with additional funds from partners and landowners to a total investment of $424.5 million. The Sage Grouse Initiative has been targeted toward the most important regions and aids ranchers with NRCS technical and financial assistance and in getting NRCS conservation practices on the ground. Efforts range from establishing conservation easements that prevent subdivision of large and intact working ranches to improving and restoring habitat through removal of invasive trees. Across the range, conservation easements have increased 18-fold through the Sage Grouse Initiative, protecting 451,884 acres.

Privately Led Efforts

Efforts to conserve greater sage-grouse habitat are not limited to state and federal agencies. Industry and private landowners are also developing means of conserving the greater sage-grouse. In April 2015, the Secretary of the Interior announced an agreement with Barrick Gold of North America to create a greater sage-grouse conservation bank that protects important habitat for the species on lands controlled by the mining company as mitigation for impacts caused as the company proceeds with their gold mining activity.

In March 2015, the Secretary of the Interior announced the approval of the privately held Sweetwater River Conservancy Conservation Bank for the greater sage-grouse on more than 55,000 deeded acres in central Wyoming. Not only was this the first conservation bank for greater sage-grouse, it is the largest habitat conservation bank in the United States. The bank establishes habitat credits, based on extensive data on greater sage-grouse habitat use and habitat preference and the identification of functional population segments over a wide area including private, state, and federal lands. The credits can be used to offset impacts to greater sage-grouse within the bank’s service area, essentially the range of the species within the state. The private lands are protected through a perpetual easement and managed in accordance with the Conservation Bank Agreement approved by the FWS. The revenue for protection and enhancement of this habitat is generated through the sale of the habitat credits. According to the FWS the bank has the potential to expand to 700,000 acres on lands owned by the Sweetwater River Conservancy.

LCC ROLE IN CONSERVATION OF THE GREATER SAGE-GROUSE

The historic and current range of the greater sage-grouse includes portions of four LCCs. Although the greater sage-grouse conservation issue predates the development of the LCCs, the LCC Network has contributed $2.25 million and staff support to 27 greater sage-grouse projects. Much of the LCC money and staff were leveraged, allowing stakeholders to tackle much larger problems than would have been possible individually. For example, the Inter-LCC Collaborative Sage-Grouse Project received $500,000 from the FWS, which they leveraged for $941,000 of other funding for specific projects with range-wide application and demonstrating their collaborative nature. The following are examples of projects that were funded to contribute to existing sage-grouse conservation efforts mentioned above.

Great Northern LCC

In their draft Science Plan, the Great Northern LCC (GNLCC) lists the greater sage-grouse and its habitat, sagebrush/grassland, as conservation targets and the greater sage-grouse as an umbrella species for the sagebrush steppe landscape. The GNLCC has contributed more than $750,000 to eight ongoing or completed projects either directly or indirectly related to the greater sage-grouse. Examples of what these studies contributed follow:

- Created a habitat model for greater sage-grouse in the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion; tested connectivity model predictions for greater sage-grouse and focal species tied to sage-steppe ecotypes (black- and white-tailed jackrabbits); integrated model testing results in an adaptive management framework to inform conservation action within the area of the GNLCC, and communicated to shareholders.

- Provided high-resolution connectivity maps for greater sage-grouse in the Great Northern landscape using state-of-the-art genomics. The project resulted in a manu

___________________

measures will not change should listing occur. In contrast, a CCAA is a voluntary agreement between the FWS and participating private property owners with a permit issued by the agency containing assurances that if the private property owners engage in certain conservation actions for species included in the agreement, they will not be required to implement additional conservation measures beyond those in the CCAA if the species is listed in the future. Also, in the case of a CCAA, additional land, water, or resource use limitations will not be imposed on them should the species become listed in the future, unless the landowners consent to such changes necessary (http://www.fws.gov/endangered/esa-library/pdf/CCAs.pdf).

-

script prepared for publication and allowed the identification of genes that code for disease resistance and adaptive selection, such that consideration of adaptive differences can be used in management of subpopulations.

- Monitored for 5 years vegetation, fuels, wildlife, insects, and weather at 10 Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project (SageSTEP) sites, all of which were treated to reduce either juniper encroachment (woodland sites) or cheatgrass invasion (sagebrush/cheatgrass sites).

- Identified greater sage-grouse populations at risk of extinction within the GNLCC based on their relative isolation from neighboring populations and core regions of the greater sage-grouse. These results benefited management agencies by focusing regional conservation and land management options in regions likely to sustain long-term sagebrush ecosystems (Knick et al., 2013).

Great Basin LCC

For 2013 and 2014, the Great Basin LCC identified short-term science priorities to guide research (Hughson et al., 2011). The Great Basin LCC is preparing a longer-term plan to guide research for the next 5 years. The Great Basin LCC has contributed more than $825,000 in the funding of 10 projects directly or indirectly related to the greater sage-grouse. Examples of these projects include the following:

- Assessment of impacts of feral horses and livestock grazing on sage-grouse habitats: long-term trends in greater sage-grouse demography and habitats on the Sheldon-Hart Mountain. This project takes advantage of historical patterns of grazing by both feral horses and livestock and new data to assess greater sage-grouse population dynamics and habitats under all combinations of grazing by nonnative ungulates.

- Forecasting changes in sagebrush distribution and abundance under climate change: integration of spatial, temporal, and mechanistic models. The goal of this project is to forecast the effect of climate change on the distribution and abundance of big sagebrush in order to inform conservation planning, and sage-grouse management in particular, across the Intermountain West. The novelty of the work will be the synthesis of models based on spatial, temporal, and mechanistic relationships between climate and sagebrush cover.

- Strategic high-resolution wetland mapping in greater sage-grouse biologically significant areas of Nevada. This effort is a direct result of the Great Basin LCC-led Central Basin & Range Rapid Ecoregional Assessment (CBR REA) Challenges and Opportunities Report, which identified a paucity of available wetland and springs data layers for the CBR REA area. This project will provide wetland mapping at high resolution (1:24,000) for 13 million acres of greater sage-grouse biologically significant areas within Nevada.

Plains and Prairie Potholes LCC

We found no formal plan for research for the Plains and Prairie Potholes LCC (PPLCC) or any specific research objectives related to the greater sage-grouse. However, the LCC provided support for three projects directly or indirectly related to the greater sage-grouse, including

- An evaluation of the impact of conservation-oriented, rest-rotation livestock grazing and climate changes on migratory bird species associated with sagebrush habitat to better inform grazing management practices. While this project was not directly related to the greater sage-grouse, rest-rotation grazing management is likely to enhance important components of sagebrush, shrubland, and grassland habitat for a wide range of species including greater sage-grouse.

- An investigation of the construction and operational effects of wind energy development on greater sage-grouse through the study of survival, movements, habitat use, and lek dynamics, on a 1,000-turbine, 2,000- to 3,000-megawatt wind facility in Carbon County, Wyoming, using a before-after control-impact design. Another study was successful in addressing the study objective of evaluating the impact of wind energy development on greater sage-grouse.

- The development of a rapid assessment method for wildlife issues at potential wind energy sites.

Southern Rockies LCC

No research plan was found for the Southern Rockies LCC (SRLCC), the fourth LCC including a portion of the current range of the greater sage-grouse. The list of ongoing or completed projects on the SRLCC website included two projects related to the greater sage-grouse: $250,000 funding contributed to the Western States Crucial Habitat Assessment Tools; and contributions to the development of a Regional Model for Building Resilience to Climate Change: Development and Demonstration in Colorado for the Gunnison sage-grouse.

Inter-LCC Sage-Grouse Initiative

Because of the nature of the boundaries of the states and the LCCs, it is difficult to coordinate research and management on a wide-ranging species such as the greater sage-grouse. While federal and state governments have worked tirelessly at trying to collaborate on transboundary initiatives, the four LCCs have been focused on smaller-scale projects typically on specific issues within each LCC boundary. And in the case of the SRLCC, the focus has been heavily weighted toward water issues. Region 6 of the FWS administers two of the four LCCs containing greater sage-grouse habitat. In an effort to address larger-scale issues, Region 6 applied for funding from the national LCC Network for large-scale greater sage-grouse projects that transcend LCC

boundaries. Although the region requested funding of $2.54 million spread over 3 years, it was successful in obtaining a grant of $500,000 from the LCC Network office. This money was used to solicit proposals for landscape-scale greater sage-grouse research and management.

The region issued a call for proposals for funding collaborative research and management support projects through WAFWA and Region 6 of the FWS, called the Inter-Landscape Conservation Cooperative (Inter-LCC) Greater Sage-Grouse Initiative.6 Region 6 developed an agreement with WAFWA to collaboratively deliver two specific prongs of this initiative:

- Funding support for priority greater sage-grouse research and management projects.

- Supporting the identification and incorporation of existing data sets on greater sage-grouse and sagebrush ecosystems important to greater sage-grouse into the Landscape Conservation Management and Analysis Portal (LC MAP).

Several projects were funded through the initiative, including the following four projects:

- Range-wide sampling design for population size and trend estimation in greater sage-grouse;

- Sage-grouse hate trees: A range-wide solution for increasing bird benefits through accelerated conifer removal;

- Designing regional fuel breaks to protect large remnant tracts of sage-grouse habitat in Idaho, Oregon, Nevada, and Utah; and

- Forecast trends in sage-grouse populations by predicting future changes in habitat due to fire (Nevada) and climate change (Wyoming).

___________________

6 See http://greatnorthernlcc.org/sites/default/files/lc_map-sage-grouse_rfp_final_v5.pdf.