Digital Model–Based Project Development and Delivery: A Guide for Quality Management (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

State departments of transportation (DOTs), tollway agencies, local governments, and other infrastructure owners and their representatives can use this guide to solve two core issues associated with digital project delivery: how to implement methods for reviewing three-dimensional (3D) models and use 3D models to review designs in new ways. To solve these issues, the guide provides contextual information—including definitions and essential design quality–management principles—and aligns the relevant design codes and standards with categories of reviews based on a reviewer’s skill set and expertise.

The introduction of 3D modeling technology to design and—more specifically—the design-review process is ongoing. While this guide represents a snapshot in time of the available technology, it is also forward looking. The chapter on implementation identifies opportunities to automate aspects of the review process with software, even though the tools to do so may not exist yet. Finally, the guide offers appendices with resources for implementation. These resources include checklists and sample quality artifacts, which are auditable records of quality checks that have been performed, in use at the time of writing. These resources will quickly be replaced, but they are included to help agencies visualize what quality management tools and artifacts may look like and help expand current checklists.

Using this guide, an agency will be able to identify new roles and responsibilities, create or update resources and checklists, and implement standardized and repeatable review processes for different 3D model reviews following International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 19650 processes. This guide is intended for state DOT quality managers, agency process implementers, and technical reviewers.

1.1 Significance of This Guide

State DOTs, tollway agencies, local governments, and other infrastructure owners have been adopting 3D modeling workflows for over a decade, beginning with the production of 3D design models and mechanisms for using those models in construction. Yet there has been a lag in updating design quality–management frameworks so they can accommodate new media to develop, review, and deliver the design information. This guide serves as a national, software-agnostic resource that agencies can use to update their quality management programs for 3D model–based design and digital delivery.

This report outlines an approach for updating an agencywide quality management program to address changes in workflow, media, and processes engendered by digital delivery. It provides a holistic view of how the use of digital media (including 3D models) affects the quality process. The guidance offers pragmatic suggestions for current conditions, where there are significant gaps in available technology solutions, and will remain relevant as more comprehensive solutions

become available. Appendices contain real-world examples from recent projects. This report is not a turnkey collection of job aids that can be inserted into an existing quality management system; instead, agencies can use it as a resource.

1.1.1 Need for This Guide

The emergence of 3D model–based design has created several gaps in design quality–management processes:

- Long-standing quality management procedures for reviewing designs are based on 2D plans and struggle to handle the content of 3D models or to take advantage of 3D model views to scrutinize designs in new ways.

- Experienced design managers who do not use the latest 3D modeling software may be creating a skill gap within the largest pool of qualified design reviewers.

- Currently available 3D modeling software focuses on design tools and does not adequately address the needs of reviewers, who do not need to edit models. This creates onerous training burdens and makes reviewers reluctant to interact with models.

- Documentation of the quality control (QC) process, including comments and responses located on or attached to model elements or views, is a new process and can be cumbersome.

Agencies need actionable guidance on how to update their quality management frameworks to address risks associated with delivering design information using new 3D model media. These risks can be mitigated by capitalizing on opportunities to review designs in new ways, addressing 3D modeling skill gaps and software limitations, and meeting new requirements for paperless quality documentation.

This guide addresses these needs by providing new types of reviews, new approaches to digital review documentation, opportunities for introducing new software tools and features, and sample checklists and quality artifacts. It can serve as a national industry reference for 3D model–based project delivery and provides a consistent, repeatable, reproducible, and traceable quality management process whose rigor and accuracy equals or exceeds paper-based processes. The guide also defines consistency, repeatability, reproducibility, and traceability in terms of the quality management process.

The need for this guide was identified as part of the study’s literature review and researcher interactions with highway agencies during conferences and AASHTO technical committee meetings.

|

Consistency: When following the procedures, the level of performance does not vary greatly over time. |

|

Repeatability: The methodology has been tested by the same qualified person using the procedures many times to verify that the review process is correct so it can be standardized. |

|

Reproducibility: The procedures capture the steps for performing each review well enough that they can be reproduced by any qualified person to achieve the same results. |

|

Traceability: The process enables any qualified person to track the record of decisions for all reviews performed. |

1.1.2 Scope of Guide Content

This guide addresses reviewing designs using 3D models and reviewing 3D model–based deliverables, including data validation and documentation procedures. It includes the following:

- Recap of design quality–management principles (Chapter 2),

- Considerations for working with digital records and quality artifacts (Chapter 3),

- The connection between information management standards and quality management for project design (Chapters 4 and 5), and

- Suggestions for implementing these guidelines (Chapter 6).

1.2 Quality Management Objectives

This guide advances three quality management objectives:

- Manage risk and trace accountability.

- Follow a multilayered approach.

- Align the quality management process for 3D models and 3D model–based design with the ISO 19650 information management standards for Building Information Modeling (BIM).

1.2.1 Risk Management and Accountability

Quality management is a process with various tools to systematically manage risk and trace accountability. The use of new, 3D model media introduces new types of potential defects, changes the risk profile of potential design defects, and creates barriers to accessing information that are not an issue with paper documentation. Chapter 3 addresses the need for management of digital records and paperless quality artifacts, while Chapter 5 discusses how to update a quality management framework to proactively identify and manage potential defects.

1.2.2 Multilayered Approach

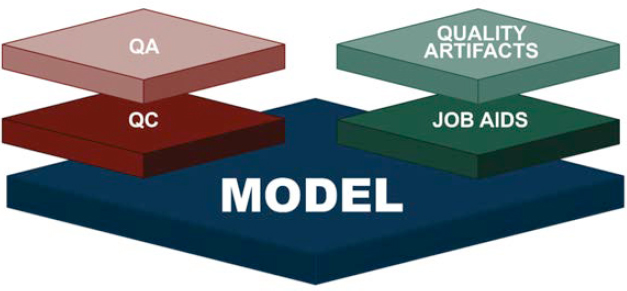

An effective quality management program has built-in redundancy to avoid single points of failure. Quality management frameworks build in redundancy through QC and quality assurance (QA) and by planning how the QC roles are executed. The guide addresses QC through sample job aids and quality artifacts as well as by providing detailed checking procedures for each review type. QA needs are addressed through sections on paperless quality artifacts and digital records management (Figure 1).

Standardized review procedures and job aids help reviewers check for known defects—but by design, they cannot help reviewers look for unanticipated types of defects that may be present.

Section 2.1.1 identifies the need for performance monitoring, documenting the issues that arise in construction, and routine review and updates to the job aids to look for items that slipped through the cracks and resulted in large or consistent cost overruns, delays, or workplace injuries. Once new defect types are identified, job aids and checking procedures need to be updated.

1.2.3 Information Management Standards, Methods, and Procedures

Information management standards contain guidelines, procedures, and best practices for managing data and information within an organization. Standards referenced throughout this guide include

- ISO 7817—Building Information Modeling: Level of Information Need,

- ISO 9000 series—Quality Management Systems,

- ISO 15489—Standard for Records Management, and

- ISO 19650 series—Building Information Modeling.

Implementing methods and procedures that align with international standards allows agencies to maintain a consistent and reliable approach to quality management. Each standard plays a crucial role in defining the use of BIM throughout the project life cycle and, in turn, the quality management required to manage the delivery of reliable information.

BIM is a carefully managed approach to collaboration using digital data and, in particular, 3D models. When BIM is used for a design project, it begins with a BIM Execution Plan (BEP) which lays out a clear plan for creating 3D models to develop, review, and document the design. Switching from 2D plans to a BIM workflow transforms information sharing but opens agencies to risks regarding quality management. The content of this guide aligns with BIM management best practices so that agencies can more easily integrate new quality management procedures and tools into their emerging BIM standards. ISO 7817, adopted as a standard in June 2024, introduces a robust way to describe levels of detail and information for model elements. Note: This guide uses the ISO standard terminology, Level of Information Need (LOIN), instead of Level of Development, which readers in the United States may be more familiar with.

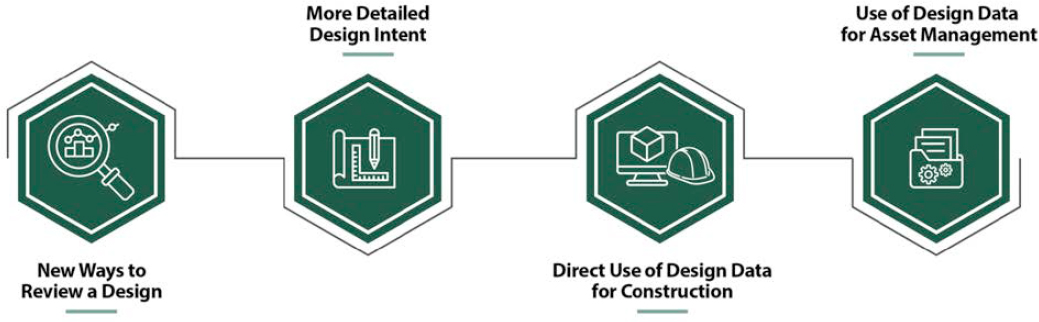

1.3 New Opportunities

The use of new media presents novel opportunities for design reviews and construction documents. This guide provides suggestions on how to realize these benefits, and it incorporates these opportunities into guidelines for the overall quality management processes for 3D models. Figure 2 defines these new opportunities.

1.3.1 New Ways to Review a Design

Many benefits of using 3D model–based designs arise from being able to communicate design intent and inspect designs in new ways. A few benefits include new ways to

- Check sight distances and explore designs from motorist perspectives.

- Automatically detect spatial conflicts, including prescribed buffers around specific asset classes.

- Evaluate quantities directly from model elements using attributed pay item numbers.

- Utilize open data standards and automation tools in project team reviews.

1.3.2 More Detailed Design Intent

Using 3D model–based designs to communicate design intent in greater detail carries numerous benefits. These include the ability to

- Detail all transition areas along a roadway, including merge and diverge areas, driveways, grading around roadside appurtenances, and superelevated sections.

- Analyze drainage through areas with complex geometry.

- Visualize a design without needing to interpret 2D sections.

- Visualize construction staging and maintenance as well as protection of traffic or traffic control during design to identify issues.

- Visualize a design so that design intent can be communicated to external stakeholders, such as attendees of public information meetings and environmental agency personnel with jurisdiction.

- Demonstrate complex interactions between elements, such as steel reinforcement.

1.3.3 Direct Use of Design Data for Construction

One of the biggest changes from 3D design model data arises from its direct use in construction, which can save time during bidding and provide efficiencies throughout construction. Model-based information can be delivered in different formats, such as

- Spreadsheets or other tabular formats;

- 2D or 3D vector graphics in PDF files;

- Open format exports, including LandXML files at the time of writing and Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) files in future; or

- Proprietary 2D or 3D model files.

Each format has a different level of sophistication and, in some cases, requires specific software to correctly access information within it. This guide describes processes on how to prepare and review these 3D deliverables.

2D PDF files are deeply embedded in traditional contractor workflows for estimating, mobilization, layout, and execution. Open file format exports are compatible with most software tools used to prepare construction layout data. Some contractors feel comfortable relying on this data, while others use PDF plans as an underlay to verify that the data has imported correctly. Data in proprietary formats has less universal support and requires increased sophistication to interact with it. Designers should consider what is needed for data exchange, and they should both prepare and review the contractual deliverables with this in mind. If explicit instructions are needed to reconstruct the design information, then those instructions must also be reviewed.

When considering how a contractor may use design model information, it is important to think about the distinction between communicating design intent and attempting to prescribe the contractor’s means and methods. One such example involves construction layout information,

with surface models for automated machine guidance (AMG) in particular. While it is possible to deliver a surface model in a format that AMG equipment can process, a contractor must go through several steps, either by converting design intent information into data on the AMG system or by creating a construction model to import directly into the equipment. A contractor’s steps to verify data include survey setup for layout equipment, checking the actual ground compared to the design-surveyed existing ground conditions and design tie-ins to onsite conditions, and the specific needs of the AMG operators. Another way that design model data can be given to contractors is by providing IFC files in the bid package for fabrication of different components, such as steel reinforcement and girders, which is then provided to suppliers for bidding purposes and fabrication.

1.3.4 Use of Design Data for Asset Information

Another new development arising from digital delivery for design is the use of design models to establish a base for asset information that can be delivered after construction through the asset models or record or as constructed models. For transportation projects, property sets are applied and model elements are tagged after construction on a case-by-case basis across the United States. Asset information embedded in 3D design models and asset information deliverables extracted from a design may need to be reviewed by parties not traditionally involved in the design-review process. These parties may be part of agency divisions or departments such as asset management or geographic information system (GIS), and they may have limited knowledge of 3D design models. New workflows, trainings, and educational opportunities need to be created for these reviewers.

1.4 New Challenges

Existing design-review routines and documentation depend heavily on paper-based processes. A typical approach is to highlight plan elements in one color and markup issues in another color as they are checked, and have the back checker and corrector apply marks in other colors as they comment and track concurrence or completion.

Paper-based workflows can be replicated on “electronic paper” in a PDF file where digital plan sheets are marked up. PDF is also a convenient format to consolidate copies of the reviewed documents with the quality artifacts. This approach avoids the risk of broken links to file locations when a project moves to archival storage.

New challenges arise when an agency moves away from “electronic paper” and utilizes model-based approaches, as identified in Figure 3.

1.4.1 Paperless Design Calculations

Engineers use many different types of software to assist with design computations. Some of these products are commercial off-the-shelf software and others are bespoke, manually created spreadsheet models or programs, such as MathCAD worksheets. The use of paperless design calculations is not a new practice within the industry, but there are new challenges with the accelerated creation and usage of calculations performed by software. These challenges include timely validation of software or bespoke spreadsheets, which can be time-consuming and cumbersome.

Paperless design computations need to be archived so they are accessible over the life of the facility. This means that software-dependent information needs to have the software archived with it, or the calculations need to be archived in a durable and accessible format. Section 2.1.4 discusses process and product control, while Section 3.2 discusses how to manage these digital records.

Intermediate deliverables—incomplete products of design processes—should be reviewed with an eye toward their intermediate condition, their role in the development process, and previously agreed-upon expectations for their level of precision. However, they should still be reviewed in a timely manner that supports further decision-making and sustains the project’s momentum. While most of the industry may have practices in place for checking paperless design calculations, agencies should review their current practices and incorporate defined procedures, if necessary. (See Chapter 6.)

1.4.2 New Media for Executing Reviews

The software landscape is dynamic, with new products and features constantly being developed. Challenges faced with new media include the limited number of software packages that can view 3D models created in a different design authoring software. Choosing a particular review software also highlights challenges with proprietary design authoring software and the interoperability of a specific software. Open data standards will provide an opportunity to use new file formats and software, such as IFC and BIM Collaboration Format (BCF), that may not have been considered before. Section 6.4.3 explores the use of open data standards as part of a prospective solution for expanding the usability of review software.

Another challenge of using new media today is that reviewers need access to specific support configurations and software competencies to obtain the necessary information to perform the review. To perform reviews, agencies may also need software that differs from what was used to prepare designs. This software might have features to track reviews, especially to gather evidence of content being checked when no issues are identified. In either case, the review documentation will need to consider the need for auditable quality artifacts. Chapter 5 expands on model development standards as well as review tools and job aids that can be used to execute reviews using a new medium.

1.4.3 Auditable Quality Artifacts

Quality artifacts need to be in a durable format that is accessible to the quality auditor using commonly available software and typical skill sets. This generally means that the quality artifacts exist in a separate file (and in a different format) from the 3D models that contain the design information. Each quality artifact needs to identify which digital files are related to the documented review, either explicitly or with metadata. Artifacts should also show a complete record of the QC process, including verification and closure sign-offs, as discussed in Section 2.3.2.

Artifacts should be accessible to the extent that legal responsibilities for records retention are fulfilled. Consult state law or agency guidance to establish file format types or specific terms of design versions retained.

1.4.4 New Media for Construction Contract Documents

It can be challenging to archive and manage new media file types that may not be accessible for future audits. Section 3.2.1 offers suggestions for interim solutions during this transition period. Agencies can also explore industry trends with open data standards and new technical solutions that can be implemented in the future.

At the time of writing, AASHTO is working on a national standard Information Delivery Specification (IDS), which is a computer-readable way to interrogate an IFC file and compare the data to the standard. By connecting to the buildingSMART Data Dictionary content that defines the information requirements in detail, an IDS can be used to automate part of the model integrity review. Construction inspection staff and construction bidders also need access to software that provides the project’s design information and 3D models.

Paperless contract documents need to be archived so they are accessible over the life of the facility. This means that proprietary 3D model–formatted information needs to have dependent software versions, configurations, and model structures thoroughly documented so the information can be accurately reconstructed, particularly after the design moves to archival storage. Agencies may also want to consider version control and indicating the status of the paperless construction-contract documents.

1.5 Appendices

This report contains six appendices, described as follows:

-

Appendix A: Glossary.

- – Defines 3D modeling and quality management terminology related to project development and delivery.

-

Appendix B: Model Elements Taxonomy.

- – Shows how model elements are classified into groups and disciplines.

-

Appendix C: Review Documentation Property Set.

- – Provides a collection of 3D modeling terms, definitions, references, synonyms, attributes, and metadata relevant to the design and 3D model–review process and documentation.

-

Appendix D: Competencies.

- – Organizes sample core competencies by computer-aided design and drafting (CADD), common data environment (CDE), and design.

-

Appendix E: Review Procedures.

- – Walks through sample steps for the core review processes: review initiation, modeling standards review, model integrity review, survey, discipline design, and clash detection and spatial coordination.

-

Appendix F: Sample Quality Artifacts and Checklists.

- – Provides examples of different types of quality artifacts discussed throughout the guide.