Implications of Artificial Intelligence–Related Data Center Electricity Use and Emissions: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 5 Sustainability Analysis of Data Centers

5

Sustainability Analysis of Data Centers

Eric Masanet, University of California, Santa Barbara, moderated a panel discussion focusing on the environmental and social repercussions of artificial intelligence (AI) data centers, both locally through land, water, and energy demands as well as globally from increased emissions, supply-chain impacts, and pollutants generated throughout the life cycle of data center equipment and infrastructure. The panelists were Davide D’Ambrosio, International Energy Agency (IEA); Julie Bolthouse, Piedmont Environmental Council; Laura Gonzalez Guerrero, Clean Virginia; Sarah Boyd, Aligned Incentives; and Cooper Elsworth, Google.

PANELIST REMARKS

Data Center Electricity Demand Growth

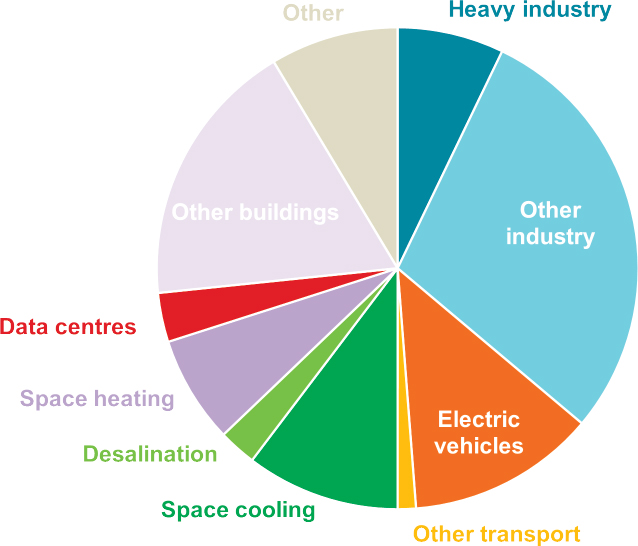

D’Ambrosio shared IEA findings regarding the current and future energy demands of data centers. While data centers account for a relatively small part of the overall projected growth in electricity demand through 2030 (Figure 5-1), they are growing fast globally and nationally, and investment in them has outpaced clean energy investment.1 Compared to other types of industry facilities like steel plants, factories, mines, and even warehouses, data centers also show a high tendency to

___________________

1 International Energy Agency (IEA), 2024, World Energy Outlook 2024, IEA Publications, https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024.

NOTE: See https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-and-climate-model/stated-policies-scenario-steps and https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-and-climate-model/understanding-gec-model-scenarios.

SOURCE: Davide D’Ambrosio, IEA, presentation to the workshop, November 12, 2024. CC BY 4.0.

cluster in the same geographic areas. This clustering is driven by a need for data centers to be located close to available infrastructure, power supply, customers, and workforce; however, it also creates strains on local communities and utilities.

D’Ambrosio emphasized that numerous sources of uncertainty around data and AI deployment, technological advances, and efficiency improvements impede the ability to accurately project U.S. data center energy demands, adding that much of this uncertainty stems from a lack of clear reporting on data centers’ current energy use and operating

characteristics, requiring modelers to make assumptions.2,3,4,5,6,7 Given these uncertainties, D’Ambrosio recommended caution when modeling and using sensitivity analyses and scenario-based approaches.

Impediments to a Clean Energy Transition

Responding to the challenge of rapidly increasing energy demands—which are expected to double in the next 15 years8—creates a daunting challenge for investor-owned utilities (IOUs) such as Dominion Energy. Data centers already account for a large proportion of total load in the state of Virginia—a little over 20 percent—and that is projected to increase to 55 percent of total load by 2039. Guerrero described how, despite a Virginia law mandating the retirement of fossil fuel plants, Dominion Energy has claimed that the only way to meet the coming load is by delaying plant retirements and increasing gas-fired generation, a significant setback for the state’s path to curtailing greenhouse gas emissions.

One challenge is that the regulatory cost-of-service model followed by IOUs is inadequate to price data center demand, Guerrero said. This outdated compensation framework maximizes profits through increased capital expenditures to increase the base rate and generate more shareholder revenue, inadvertently disincentivizing cleaner, more responsible, and more cost-effective ways to manage growth. Residents would see a

___________________

2 J. Albers, V. Dahiya, A. Fraym, and J. Howe, 2024, 2024 Global Data Center Market Comparison, Cushman & Wakefield, https://www.cushmanwakefield.com/en/insights/global-data-center-market-comparison.

3 L. Greden, O. Yashkova, R. Brothers, S. Graham, n.d., Datacenter Trends: Sustainable Datacenter Builds and CO2 Emissions, https://www.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=IDC_P33186, accessed December 15, 2024.

4 A. Green, H. Tai, J. Noffsinger, P. Sachdeva, A. Bhan, and R. Sharma, 2024, “How Data Centers and the Energy Sector Can Sate AI’s Hunger for Power,” McKinsey & Company (blog), September 17, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/private-capital/our-insights/how-data-centers-and-the-energy-sector-can-sate-ais-hunger-for-power.

5 Mordor Intelligence, n.d., “Data Center Market Size & Share Analysis - Growth Trends & Forecasts Up to 2030,” https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/data-center-colocation-market, accessed December 15, 2024.

6 D. Patel, J.E. Ontiveros, and D. Nishball, 2024, “Datacenter Anatomy Part 1: Electrical Systems,” Semi Analysis (blog), October 14, https://semianalysis.com/2024/10/14/datacenter-anatomy-part-1-electrical.

7 E. Masanet, N. Lei, and J. Koomey, 2024, “To Better Understand AI’s Growing Energy Use, Analysts Need a Data Revolution,” Joule 8(9):2427–2436, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2024.07.018.

8 V.B. Link, 2024, “Commonwealth of Virginia, Ex Rel. State Corporation Commission, In Re: Virginia Electric and Power Company’s 2024 Integrated Resource Plan Filing Pursuant to Va. Code § 56-597 et Seq. Case No. PUR-2024-00184,” sent October 15, https://cdn-dominionenergy-prd-001.azureedge.net/-/media/pdfs/global/company/irp/2024-irp-w_o-appendices.pdf?rev=c03a36c512024003ae9606a6b6a239f3.

much lower energy bill in 15 years if IOUs included load growth in their ratepayer cost calculations.

Community Impacts of Data Center Growth

Building on Guerrero’s comments, Bolthouse discussed how Piedmont Environmental Council has sought to understand the impacts of data centers on communities in Northern Virginia, which is home to the largest concentration of AI data centers in the world. The organization focuses on Virginia’s Loudoun, Albemarle, and Clark counties with a mission to protect and restore the area’s lands and waters, improve air quality, and build more sustainable communities. She described how the rapid growth of data centers in this area threatens decades of conservation efforts and undermines Virginia’s clean energy and climate goals.9,10

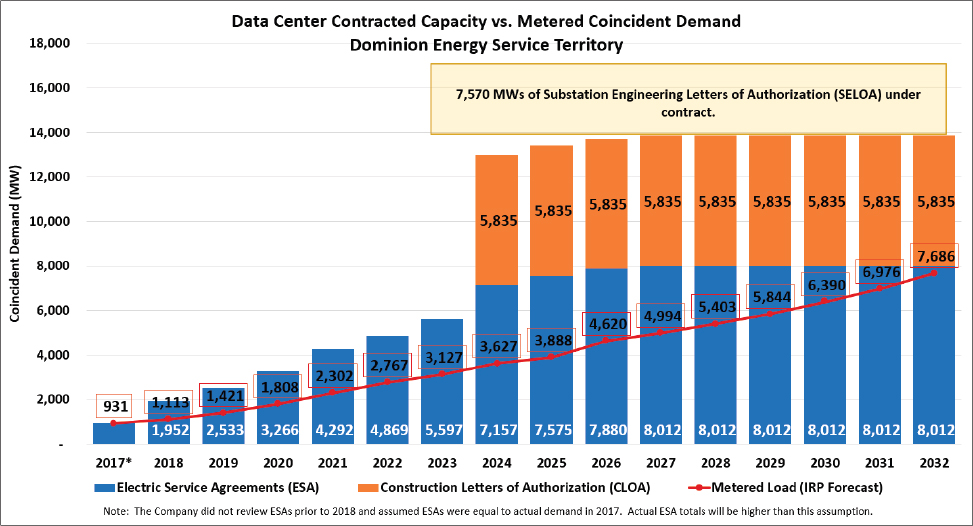

Bolthouse said that the first data centers to come to the area were built far away from protected areas and brought jobs and revenue to the community. However, as more and more energy-hungry data centers have come online, negative impacts for the surrounding communities have begun to accumulate and spread far beyond the data center locations themselves. The utilities claim that they have an obligation to provide power to customers, but she said that in reality this means they are offering power they cannot provide (Figure 5-2).11 Bolthouse also noted that the service agreements that utilities enter into with data centers lack state oversight or consideration of impacts to ratepayers. “All this is happening behind closed doors, so there’s really not that much transparency around it,” she stated.

In practice, electric utilities’ obligation to provide service to anyone who requests it within their service territory, combined with the rapid growth in customer contracts, has created a crisis that utilities say can only be solved through a return to gas-fired generation, in conflict with Virginia’s laws and decarbonization goals. In addition to spurring continued, and even increased, fossil fuel use—through the delayed retirement of coal facilities

___________________

9 Piedmont Environmental Council, n.d., “Existing and Proposed Data Centers—A Web Map,” https://www.pecva.org/work/energy-work/data-centers/existing-and-proposed-data-centers-a-web-map, accessed April 21, 2025.

10 J. Albers, V. Dahiya, A. Fraym, and J. Howe, 2024, 2024 Global Data Center Market Comparison, Cushman & Wakefield, https://www.cushmanwakefield.com/en/insights/global-data-center-market-comparison.

11 V.B. Link, 2024, “Commonwealth of Virginia, Ex Rel. State Corporation Commission, In Re: Virginia Electric and Power Company’s 2024 Integrated Resource Plan Filing Pursuant to Va. Code § 56-597 et Seq. Case No. PUR-2024-00184,” sent October 15, https://cdn-dominionenergy-prd-001.azureedge.net/-/media/pdfs/global/company/irp/2024-irp-w_o-appendices.pdf?rev=c03a36c512024003ae9606a6b6a239f3.

SOURCE: Julie Bolthouse, Piedmont Environmental Council, presentation to the workshop, November 12, 2024.

and the approval of more than 4,000 diesel-powered generators permitted as backup power—Bolthouse added that the water demands of data centers also pose a threat to communities and ecosystems. For example, Loudoun Water reported a 250 percent increase in potable water consumption from data centers between 2020–2024, with the amount of potable water used by data centers now surpassing reclaimed water.

Accounting for Cradle-to-Gate Emissions for Artificial Intelligence Equipment

Boyd discussed the emissions impacts connected with data center expansion that are embodied in data center equipment and occur before a data center even becomes operational. If the infrastructure and computing equipment necessary to build data centers—integrated circuits, semiconductors, cabling, processing units, memory, and more—were manufactured with renewable energy, their overall life-cycle emissions would be dramatically lower. While strides have been made to reduce these “cradle-to-gate” emissions, AI data centers are projected to create an additional 20–50 metric tons of carbon dioxide by 2030 under a business-as-usual scenario for the production of storage wafers, memory wafers, and processor wafers.12

Boyd said that technical solutions are needed to better understand and reduce carbon emissions during manufacturing and operations, along with policy incentives to encourage the adoption of these solutions. In the near term, she highlighted the need to increase the ability to meet supply-chain and production demands for renewable sources of energy, while using effective fluorinated emissions abatement strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions generated during certain manufacturing processes. In the medium term, she said that research is needed to advance alternative process chemistries and to develop more advanced fluorinated greenhouse gas emission abatement strategies. In the long term, she said that it will be important to optimize every part of the AI data center supply chain for minimal emissions. She added that innovative work is being done at the Interuniversity Microelectronics Centre (IMEC), and that IMEC is a close collaborator with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

These challenges are complex, involve multiple actors and fast-changing industries, and will require collaboration to create incentives and

___________________

12 O. Burkacky, M. Pototzky, D. Tang, and W. Zhu, 2024, “Generative AI: The Next S-Curve for the Semiconductor Industry?” McKinsey & Company, March 29, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/semiconductors/our-insights/generative-ai-the-next-s-curve-for-the-semiconductor-industry.

drive action. Boyd pointed to two policies from Europe that can serve as models: the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products (ESPR) Directive. The CSDDD ensures that companies have climate transition plans that address their value chain and 5-year detailed action plans that target achievement and penalize failure. The ESPR sets incentives and drives action through tracking products’ sustainability attributes.

Corporate Sustainability Commitments

Elsworth discussed the role of corporate commitments in advancing sustainability for AI data centers, highlighting the commitments made by Google and the strategies the company is employing to achieve them. Google has committed to ambitious sustainability goals to decarbonize the company’s operations. This includes reducing absolute emissions by 50 percent by 2030 from a 2019 baseline, sourcing carbon removals to neutralize remaining emissions, and running all data centers on carbon-free energy 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The rapid growth of AI data centers has posed a new challenge in achieving these targets; however, and the company is focused on advancing AI innovation without contributing to emissions growth.

To that end, Elsworth said that an important first step is to create tools that can gather more granular emissions data from data centers, enabling users to make informed decisions that minimize emissions. Action-focused emissions data will help companies understand that emissions can be broken down by workloads, AI models, customers, and products; enable the creation of carbon-aware computing optimizations that reduce specific workloads’ emissions; and match hourly workloads with clean energy availability to ensure the grid supports demand.

To support this, Google created an hourly carbon emissions monitoring tool that breaks down emissions by individual workload and location. This helps to shed light on energy supply and demand and enable the use of modeling tools to identify opportunities to make workloads more carbon-efficient, decoupling energy growth from emissions growth. For example, Google’s data centers now work harder when solar or wind generation is strongest. Cloud customers can also access these tools to maximize decarbonization.

While achieving this level of granularity has been challenging given a general lack of consensus on methods to measure AI emissions, Elsworth said that the company is confident that the tools will help to reduce data center emissions. He added that efforts are underway to improve methods to collect the granular data needed to verify that data center processes are using carbon-free energy.

PANEL DISCUSSION

In an open discussion, panelists considered a variety of issues around the impacts of data centers on energy costs and emissions, the responsibilities of different stakeholders, and the importance of addressing uncertainties. They concluded by naming what they see as key sustainability challenges along with possible research directions or policy solutions to address them.

Energy Costs and Responsibilities

Paige Wesselink, Sierra Club, said that in her view, it seems unfair that the high concentration of data centers in Northern Virginia means that a single utility (Dominion Energy) and its customers are bearing the burden of handling approximately 70 percent of the world’s Internet traffic.13 Bolthouse agreed that many of the costs associated with data center expansion ultimately wind up being unfairly subsidized by the public. Even though AI is not yet a marketable product, the infrastructure being rapidly built for it is bringing huge costs to utilities, customers’ energy bills, the environment, and public health.

Guerrero agreed, adding that utilities are not incentivized to change their business model or question data centers’ energy demands, which leaves other customers and communities to shoulder the burdens while the AI industry will ultimately reap the benefits. “How do we make sure that the costs are correctly allocated to those companies that are set to profit the most out of it and make sure that we avoid placing the risk on residential customers that are suffering the burden not only of the cost but of the natural gas facilities, the coal plants, the water issues—all the things we talked about today?” Guerrero asked. “It’s a philosophical question about who is paying and who should pay.”

Arman Shehabi, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, asked panelists to comment on why utilities do not pass on the costs of building more capacity to data centers. Bolthouse replied that IOUs make profits from new capital expenditures and also claim they cannot satisfy contract deadlines without using legacy fossil-fuel energy sources. In one case, she said that Virginia’s State Corporation Commission did not require a data center developer to pay for anything more than distribution for energy delivery, setting a precedent that new transmission lines in Northern Virginia be paid for by ratepayers. She also noted that the Data Center Coalition is a powerful lobby and said that new policies are needed to protect the public interest.

___________________

13 Northern Virginia Regional Commission, n.d., “Data Centers,” https://www.novaregion.org/1598/Data-Centers, accessed April 21, 2025.

Guerrero noted that the commission is considering charging data centers directly for new transmission lines, but developers are fighting it by arguing that that plan is discriminatory. She said that this is in line with a general pattern she sees in which industry initially expresses a willingness to pay for costs associated with their activities, but then when it comes to regulatory proceedings, they “fight tooth and nail” against paying. She praised Google for its transparency and commitment to sustainability, but expressed frustration with other companies and industry associations regarding this behavior.

Masanet asked Guerrero to explain more about what she sees as the impacts on ratepayers and suggested that energy economists could help inform solutions. Guerrero reiterated that utilities make money through capital expenditures and said that they will need new incentives if they are to align maximizing least-cost alternatives with data center demand flexibility—an approach that is rarely considered or reflected in utilities’ resource plans. In addition, she said that stakeholders need to encourage utilities to model different scenarios to account for load forecast uncertainties and avoid relying on traditional, fossil fuel–based infrastructure. The key challenge is to provide reliable power for this uncertain load without over- or under-building. She also said that ratepayers need to be protected from early-cost-recovery schemes that increase the public’s energy rates to cover investments before they are used and useful, a practice that she said has harmed consumers in South Carolina and Florida.

Elsworth suggested that data centers could break down the use of cloud services by customer and product to understand the value created by different sets of AI models and tools and potentially create separate prices for different models, noting that this approach could yield fairer pricing models as opposed to a blanket price that aggregates all data center operations.

Accounting for Environmental Impacts

Panelists discussed different approaches to understanding and addressing the environmental impacts of data center expansion. Wesselink noted that companies can claim net-zero status not only by making their data center operations emissions-free but by purchasing carbon offsets in a different region, away from the impacts they cause locally. As a result, companies may be able to claim they are supporting sustainability even as they create adverse environmental impacts in certain places. Elsworth acknowledged that the definition of net-zero can be massaged, but Google’s overall goals, to reduce emissions and support high-quality carbon removal, can be achieved by closing loopholes in carbon accounting and improving standards to ensure local and hourly matching of carbon-free loads. Bolthouse

added that regulatory oversight is needed to require transparency and ensure a level playing field in accounting for carbon emissions.

Masanet asked Bolthouse to expand on the local impacts of data center clusters. She replied that communities have some agency in solving these issues—for example, with local land use decisions. However, while the impacts of data centers to air quality, water supply, and electricity rates are felt on a regional scale, the decision makers who set policies and grant permits are focused on the local scale, are incentivized to consider revenue and tax benefits, and are not responsible for meeting state regulations. She suggested a need for more transparency and oversight at the state level so that local decision makers are better able to understand regional impacts and react to harms when utilities and data centers move too quickly with minimal supervision. For example, she said that the rush to develop data centers and expand electricity infrastructure to meet their energy demands has resulted in cemeteries being destroyed, water quality being adversely affected, and transmission lines being routed through protected areas, recreational space, and private property.

Andrew Chien, University of Chicago, asked if building infrastructure-intensive super-campuses to attract data centers would be one possible approach to minimize local impacts. Bolthouse replied that it might work in new locations, but the overall pressure on the grid is so large that creating all of that power and building new transmission lines—or even a small nuclear reactor—is an enormous challenge. Guerrero agreed that this may be a solution to one problem, but who pays for the increased cost of power is still unresolved.

Masanet asked Elsworth how AI industry stakeholders can help to drive the decoupling of AI and emissions. He replied that energy is the link between the two, and data centers present an opportunity to test decarbonization methods on a global scale. He said that careful data collection will be essential to informing efforts to decouple energy from AI performance and to decouple energy from emissions. For decoupling energy from AI performance, he noted that Google designed a full-stack data center using more efficient hardware, software, and models, improving energy efficiency by 1.5-fold. Moving data centers into the cloud will also improve energy efficiency. For decoupling the energy used for AI data centers from emissions, he said that each data center action or component must be disaggregated and monitored to optimize workloads for minimal emissions. In addition, he said that incentives are needed to push for carbon-aware data center siting and clean energy procurement to enable data centers to influence the grid hourly and bring more renewable energy online.

Boyd noted that in addition to carbon emissions, the manufacturing of semiconductor chips has high water demands. Factories’ water needs often constrain the local supply, making it important to site fabrication

facilities (“fabs”) with consideration of water availability. In addition, while fabs have waste abatement or treatment facilities, some pollutants are more challenging to abate. She said that research is under way to develop replacements or effective waste treatment for perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), a class of substances used in manufacturing processes across many sectors, which have very extended longevity in the environment. Substitution of PFAS is a major challenge, given the many applications of PFAS-containing materials in fabrication, and will take many years to accomplish.

Addressing Uncertainty

Masanet asked D’Ambrosio how the IEA views and communicates the large amount of uncertainty around data center expansion, energy, and sustainability. D’Ambrosio highlighted many sources of uncertainty that make it hard to predict data centers’ future energy needs. For example, efficiency gains in hardware and software could inadvertently drive-up electricity demand—this is known as Jevons paradox, the idea that increasing efficiency leads to higher overall consumption rather than savings. Jevons paradox is disputed in the AI community. Different economic and technological contexts, actual trends in AI adoption, shifts in AI workloads to edge devices, and sustainability efforts will all affect whether Jevons paradox will hold true. Another source of uncertainty is related to policies that lead to trade restrictions on key components and associated constraints in chip production, infrastructure, grid capacity, power generation, and permitting. The IEA, as a neutral actor, is convening a collaborative, multi-stakeholder conference to discuss these issues,14,15 aggregate critical information, share data securely, and identify solutions. Masanet agreed that such a collaboration could greatly reduce uncertainty. However, he cautioned that more data sharing is needed before analysts can fully understand the current picture and improve models to enable more accurate predictions.

Sustainability Challenges and Solutions

To close the discussion, Masanet asked each panelist to name what they see as a key sustainability challenge along with research or policy opportunities that could advance solutions.

___________________

14 IEA, n.d., “Global Conference on Energy & AI,” https://www.iea.org/events/global-conference-on-energy-ai#overview, accessed April 21, 2025.

15 IEA, 2024, “Chair’s Summary of the High-Level Roundtable on Energy & AI,” December 5, https://www.iea.org/news/chair-s-summary-of-the-high-level-roundtable-on-energy-and-ai.

Suggesting that carbon impacts would become another parameter that influences the commercial readiness of semiconductor research, Boyd posited that programs of the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 and other semiconductor research grants under NIST should require evaluations similar to IMEC’s addressing the carbon impacts of semiconductor processing and architectures early in development.

D’Ambrosio highlighted the need for greater transparency around data centers’ operations in order to more fully understand the granular energy demands and the factors that influence them, from server configurations and network and storage capacity to training and inference. Building on this point, Elsworth underscored the need for stronger monitoring and accounting standards to de-risk the growth of AI. He noted that other industries have faced similar inflection periods and built pre-competitive relationships to collaboratively redefine standards and create methods to disclose emissions that work for all stakeholders.

Bolthouse advocated for greater regulatory oversight to enforce transparency around data centers’ energy and water use. She also added that there is a need for more research to understand the potential air quality impacts from onsite generation at data centers, especially in areas where data centers are highly concentrated. Guerrero highlighted the need for more research into cost allocation. If electricity were more fairly and correctly priced, she suggested, this could drive down demand. AI services today seem free and harmless to use, but in part this is because people do not realize their true costs. “There is a gas plant built in a county in Virginia that is mostly populated by Black communities, Hispanic communities, and low-income communities—and there is a direct link between every time we [use] ChatGPT and how much emissions this gas line is producing,” she said.