Macroeconomic Implications for Decarbonization Policies and Actions: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: Global Interactions

Global Interactions

Climate change and decarbonization are multinational, multigenerational, interconnected processes in which one country’s actions can have long-term ripple effects far beyond its borders. In the workshop’s fourth session, moderated by Edmonds and Peng, panelists focused on global interactions and how the energy transition may drive changes in exports, trade dynamics, and foreign investments as countries reduce fossil fuel use and consider border adjustment mechanisms. The panelists were Benjamin Sovacool, Boston University; Valerie Karplus, Carnegie Mellon University; Ryna Cui, University of Maryland; Milan Elkerbout, Resources for the Future; and Jean-Francois Mercure, University of Exeter.

INDUSTRIAL DECARBONIZATION IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

Benjamin Sovacool, Boston University, shared lessons from net-zero industrial decarbonization efforts in the United Kingdom (Sovacool, Iskandarova, and Geels 2024), in particular the work of the United Kingdom’s Industrial Decarbonisation Research and Innovation Centre (IDRIC).1 IDRIC conducted a series of reviews examining sociotechnical policy aspects of industrial decarbonization in areas such as steel, cement, chemicals, oil refining, foods and beverages, and glass. Sovacool explained that this work underscores the sociotechnical nature of decarbonization barriers and policies; in every sector, decarbonization creates multisystem, multidimensional challenges with ramifications beyond the technological or economical. In addition, Sovacool said, each sector shows strong couplings to other sectors. This demonstrates how intertwined national economies are with global markets and trends and, importantly, also creates opportunities or leverage points by which one type of intervention can have the potential to decarbonize multiple parts of the production life cycle or supply chain.

IDRIC’s industrial challenge fund has used these findings to co-create multidisciplinary, systems-level decarbonization solutions in collaboration with re-

___________________

1 See https://idric.org/.

search and non-governmental organizations, industry and trade organizations, government and policymakers, and the public. The organization’s public-private investments in advancing competitiveness support, demonstration and deployment funding, and demand-side policies have made it what Sovacool described as “the one-stop shop for industrial decarbonization,” a model that he suggested could be emulated elsewhere in the world. Sovacool added that the United States in particular could learn from how the United Kingdom has both implemented policy and structured its research on this topic.

GLOBAL AND INDUSTRY-WIDE ENABLERS OF INDUSTRIAL DECARBONIZATION

Valerie Karplus, Carnegie Mellon University, described the need for system-wide enablers to advance industrial decarbonization and discussed examples of how international collaboration can help to facilitate these enablers on a global, industry-wide scale. Key enablers, she said, include advancements needed to evolve or replace technologies and systems; strategies to mitigate worker and community impacts and improve public understanding and acceptance; effective designs, siting, and incentives to support clean power or CCS infrastructures; and incentives to encourage organizations, institutions, and policymakers to take action to deploy decarbonization solutions.

Karplus highlighted that the Industrial Decarbonization Analysis, Benchmarking, and Action (INDABA) partnership is an example of an effort to advance industrial decarbonization by focusing on those types of enablers. INDABA is an international collaboration supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation that spans multiple sectors and stakeholders and uses various research methods and modeling techniques to inform industry-targeted decarbonization efforts, she explained. She described that by understanding industry-specific issues and creating tailored solutions, the initiative aims to advance decarbonization in high-emitting supply chain processes.

Karplus suggested that working at the industry level may make it easier to build a shared understanding and incentivize decarbonization globally. She added that this will require multinational, multi-stakeholder collaborations involving academia, industry, and other stakeholders with relevant industry expertise. She noted that trade policies can also be leveraged to accelerate industrial decarbonization.

DECARBONIZATION STRATEGIES IN ASIA

Ryna Cui, University of Maryland, discussed decarbonization strategies in Asia, where various countries are experiencing different trends and sectoral profiles in greenhouse gas emissions. Electricity generation and industrial sectors are

the main contributors to emissions across the region. Emissions are increasing rapidly in India and Indonesia but have started to decline in South Korea and Japan. China has experienced rapid growth in emissions over the past several decades, but Cui posited that the country is now entering its carbon peaking stage, suggesting that it will reach its emissions peak very soon, if it has not already occurred. She attributed this shift to China’s fast adoption of green technologies like solar and wind power generation, EVs, and batteries, which has also driven the costs of these technologies down, along with a real estate slowdown that has weakened demand for construction materials and other energy-intensive products. Given the rising contribution of green technology investment to China’s economic growth, she suggested the country could hit meaningful 2035 emissions reductions if current trends continue in renewable energy deployments, economic restructuring, and adoption of low-cost abatement opportunities.

Most Asian countries’ energy transition strategies revolve around individual pathways to energy security and economic development. Most Asian countries have lagged behind China in renewable energy and EV adoption, and Cui noted that China’s high level of investment and rapid expansion in solar and EV manufacturing creates concerns that may limit green industry development in other countries, which might struggle to catch up with China in these areas. In light of the increasing challenges of entering U.S. and E.U. markets, Cui said that China in particular is strongly motivated to build new markets in developing countries, which can help accelerate the energy transition globally. She noted that this trend does not necessarily put China in competition with the United States, where the competitive advantage centers more on high-tech, high-value industries.

CARBON BORDER ADJUSTMENT MECHANISMS

Milan Elkerbout, Resources for the Future, described CBAMs as a mechanism to support decarbonization. CBAMs are fees on imported goods based on their production emissions, akin to a tariff on carbon. Elkerbout noted that the European Union will start charging fees under its CBAM in 2026, the United Kingdom is also developing one (like the European Union, linked to its domestic emissions trading system), and there is bipartisan interest in developing a similar mechanism in the United States.

Different stakeholders support CBAMs for different reasons, Elkerbout said. He explained that they have been proposed as a way to prevent or mitigate carbon leakage (when companies move production from countries with more stringent emissions rules to those with looser emissions rules), especially for countries with stringent domestic climate policies; to protect industrial competitiveness and create a more level playing field; to incentivize other countries to adopt certain climate policies; or to reduce emissions linked to consumption. However, implementing border adjustments is a complex undertaking that requires careful con-

sideration of which products or sectors will be affected (usually basic industrial goods and electricity), how to determine fees and measure carbon, and whether any exemptions are allowed, he added. It is also important to consider how they will affect consumers, who ultimately bear the costs, Elkerbout emphasized.

CBAMs come with a number of potential political and economic impacts. Since the E.U. CBAM will provide credit for carbon prices that are already paid in another country, this setup can incentivize other countries to adopt emissions trading systems, creating a policy spillover in which actions taken in one place have unintended consequences or influence decision making in another. However, this leaves open the question of whether such responses represent a true decarbonization policy or merely an effort to dodge CBAMs, Elkerbout noted. Countries could also respond by creating retaliatory tariffs or restructuring their trade to avoid CBAM impacts. Elkerbout also noted that while the revenues generated by CBAMs could be attractive for countries, they could generate resentment if richer countries primarily reap the rewards. Finally, he highlighted that CBAMs can be extremely administratively complex to implement, requiring numerous decisions about which imports they apply to and mechanisms for enforcement.

CROSS-BORDER RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE CLEAN ENERGY TRANSITION

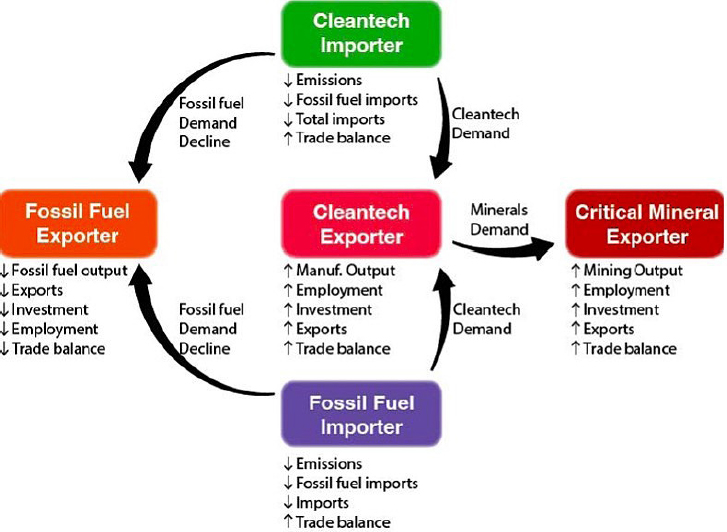

Jean-Francois Mercure, University of Exeter, posited that when and how countries decarbonize impacts other countries, potentially shaping their climate policies and economic competitiveness. He discussed how the low-carbon transition can impact cross-border risks. Outlining five archetypes reflecting different economic structures (Figure 8) (Espagne et al. 2023), he highlighted how reduced demand for fossil fuels in countries that import fossil fuels would affect output, exports, investments, employment, and the trade balance in fossil-fuel exporting countries, while increased demand for clean energy technologies could boost the economy of countries that are in a position to export the critical minerals required to manufacture these technologies.

Mercure described how these demand-driven macroeconomic outcomes can be modeled to show how different structures impact employment rates, industry, trade, and the overall economic activity of countries (Mercure et al. 2021). This has generated broad insights around the incentives different countries are likely to face; for example, large fossil fuel importers such as the European Union and China have incentive to decarbonize; Saudi Arabia and other countries in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) have incentive to capture oil and gas production and exclude other producers from global fossil fuel markets; and high-cost fossil fuel exporters like the United States, Canada, and Russia face losses but can mitigate the economic damage by maintaining domestic fossil fuel markets. However, he cautioned that modeling is complicated by the challenges inherent in predicting a country’s future behavior.

SOURCE: Espagne et al. 2023.

DISCUSSION

Following the panelists’ opening remarks, participants further discussed climate-macroeconomy interactions, modeling improvements, and considerations around the E.U. CBAM.

Climate-Macroeconomy Interactions

Carley asked panelists to remark on climate-macroeconomy interactions. Sovacool stated that it can be useful to focus on the economic benefits of decarbonization other than climate mitigation, such as benefits for resilience, employment, or innovation and competitiveness, to help garner support for industrial decarbonization even where climate is a politicized issue. Karplus noted that decarbonization also presents more countries with the opportunity to join the global supply chain and develop their economies. Building on this point, Cui said that economic development is often a stronger motivation for countries than climate mitigation, although individuals may be motivated by the extreme climate events disrupting daily life. Mercure reiterated that countries will be impacted very differently by the clean energy transition, suggesting that countries that are highly dependent on fossil fuels would be wise to broaden their economy if they want to be com-

petitive in the global race for clean technology. Elkerbout added that the different ways to achieve industrial decarbonization, such as electrification or CCS, will also have different impacts in different geographic areas.

Instead of framing policy as either climate-led or development-led, Field asked whether it would be helpful to use both frames and shift the emphasis in response to political or international relations considerations. Mercure stated that climate mitigation and economic development are not necessarily at odds with each other, despite often being framed that way. Countries can—and increasingly do—see decarbonization as a development opportunity, a framing that he suggested can improve global engagement and acceptance. However, Sovacool cautioned against a purely geopolitical frame and suggested that it can be useful to emphasize the economic potential of decarbonization innovation, which he described as a “$100 trillion opportunity.” Elkerbout agreed that while a geopolitical frame may not always be useful, he noted that it does significantly impact policies, especially around border adjustments and protectionism, which can be contentious.

Sovacool also highlighted the equity and justice benefits of pursuing decarbonization in ways that can revitalize under-resourced communities. “I think it’s very telling that many of the areas most in need of jobs and growth and resilience and energy justice are the same communities where we will do industrial decarbonization,” he said. Karplus agreed that framing decarbonization as energy justice is important globally, and she also emphasized the importance of prioritizing how one country’s policies affect others, especially in the long term or unintentionally. Cui also agreed, stating that this interconnectedness is an enormous challenge.

The panelists also discussed considerations specific to particular fuels and technologies, such as hydrogen, CCS, and oil and gas. In light of the high degree of uncertainty in the trajectories of hydrogen and CCS, Sovacool expressed support for the United Kingdom’s prioritization of energy efficiency, which offers a more certain path to decarbonization with clear domestic and global benefits and opportunities. Hallegatte pointed out that cross-border effects will likely be affected by differences in the types of fossil fuels different countries produce and export; for example, OPEC countries are central to oil while the United States and Qatar will drive what happens with natural gas. Mercure stated that oil and natural gas are affected differently by decarbonization, on both the supply and demand sides. Oil is affected most by EV adoption, wind, and solar; by contrast, natural gas, mostly used in industrial processes, does not yet have an immediate competitor. However, it is very likely that both oil- and gas-exporting countries who choose not to expand their economies will find the energy transition challenging, he said.

Modeling Improvements

Shepard asked panelists to comment on modeling approaches and, in particular, about the role for shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs), which outline five pathways the world could take in the coming decades, in modeling. Sovacool suggested that researchers could look more broadly for modeling improvements, incorporating relevant evidence from many other disciplines. While acknowledging that models are useful, he suggested that today’s climate discourse may be overly reliant on modeling projections, especially given the high degree of uncertainty.

Mercure agreed that current models need more detail and a deeper understanding of economic structures, especially cross-border investment, to better project global interactions, and he posited that current SSPs are not up to the task. He also suggested focusing on efforts to better represent global interactions in modeling for a less Western-centric perspective. Cui agreed with Sovacool and Mercure and said that more research and modeling improvements are needed, especially in the global context and with a global perspective, such as by better accounting for materials in models or coupling emissions and trade models. Elkerbout agreed that improving models is important work, noting that better models could also help to shed light on potential areas of policy spillover.

Karplus emphasized the importance of building broadly applicable shared tools, including models, and cross-sector collaborations to navigate disagreements, uncover assumptions, and present qualitative evidence of the effectiveness of policies, especially at the global level. Edmonds agreed on the need for a broad suite of tools but argued that SSP conventions are useful because they increase inclusivity and participation and enable comparisons across different modeling platforms and resolutions.

The E.U. CBAM

Pascal Weel, Federal Reserve Board, asked panelists to further discuss the effectiveness of the E.U. CBAM as a carbon pricing tool. Elkerbout replied that the European Union’s approach is fairly restrictive in that it expects exporters to provide data on embedded carbon in goods. When asked if the E.U. CBAM could prevent the emergence of dual markets for clean or “dirty” energy goods, Karplus replied that while dual markets may emerge, policy spillovers from different countries are extending the emissions trading system. This, in turn, could potentially enable carbon pricing instruments and fuel the growth of legitimate, responsible supply chain companies, creating a global system that can prevent a “dirty” economy from emerging. Elkerbout added that the design of the E.U. CBAM is unlikely to itself prevent a dual market, and he noted that differentiation between clean and “dirty” goods is not necessarily bad and could even accelerate

uptake of clean-energy goods. In addition, he suggested that countries considering border adjustments could study direct and indirect impacts on other countries and determine ways to reinvest adjustment revenue into decarbonization.