Creating a Handbook for Successful No-Effect and No-Adverse-Effect Section 106 Determinations (2025)

Chapter: State of Practice Survey

STATE OF PRACTICE SURVEY

ONLINE SURVEY RESULTS (AGENCIES AND ORGANIZATIONS/CONSULTANTS)

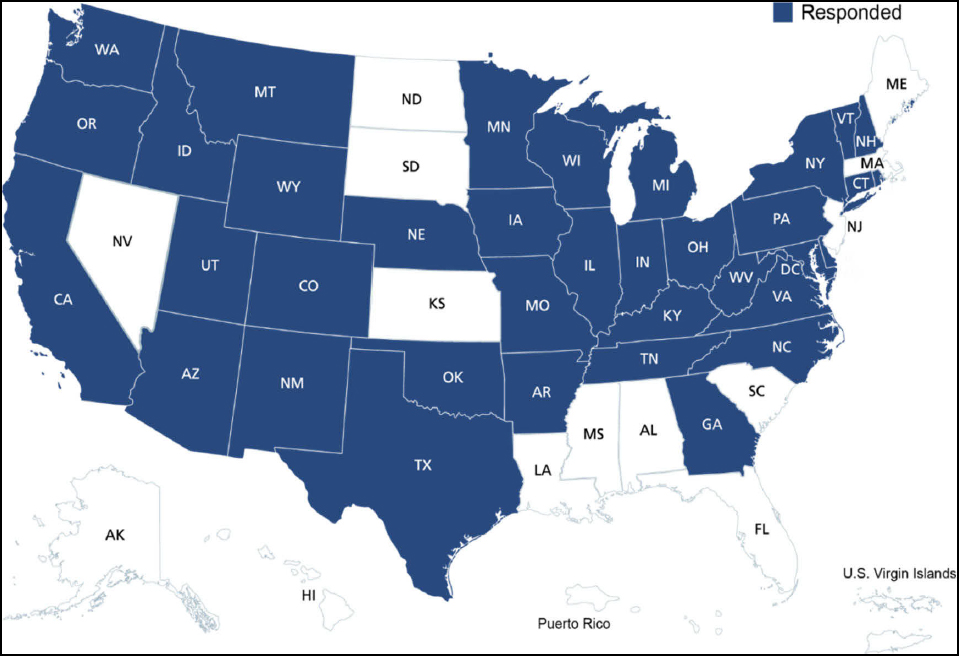

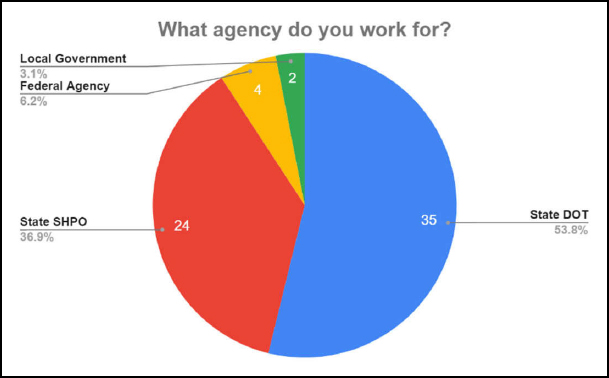

Sixty-seven responses were received from 36 out of 50 states (23 SHPOs, 26 state DOTs, three FHWA Division Offices, and two local governments), a 67 percent response rate (Figure 2). Of these 67 responses, four respondents requested to participate in an interview rather than complete the online survey (identified with an asterisk in Table 2). Twelve states sent responses from both the state DOT and SHPO, and 12 states sent responses from multiple staff within the agency (Figure 3; Table 3). Two additional surveys were received from FPOs (FHWA and FRA). Appendix A contains a matrix of the results of the online survey sent to agencies.

TABLE 2: TOTAL STATE OF PRACTICE ONLINE SURVEY RESPONDENTS BY STATE AND AGENCY

| STATE | SHPO RESPONSES | DOT RESPONSES | FHWA RESPONSES | LOCAL GOVERNMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 1* | - | - | - |

| Arkansas | - | 1 | - | - |

| California | - | 2 | - | - |

| Colorado | - | 3 | - | - |

| Connecticut | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Delaware | - | 1 | - | - |

| Georgia | 2 | - | - | 1 |

| Idaho | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| Illinois | 1 | - | - | - |

| Indiana | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Iowa | - | 1* | - | - |

| Kentucky | 2 | - | - | - |

| Maryland | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Michigan | - | 1 | - | - |

| Minnesota | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Missouri | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Montana | 2 | - | - | - |

| Nebraska | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| New Mexico | 1 | - | - | - |

| New York | - | 1 | - | - |

| North Carolina | 1 | - | - | - |

| Ohio | - | 2 | - | - |

| Oklahoma | - | 1 | - | - |

| Oregon | - | 3 | - | - |

| Pennsylvania | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Tennessee | 1 | - | 1* | - |

| Texas | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| Utah | - | 2 | - | - |

| Vermont | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Virginia | - | 2 | - | - |

| Washington | 1 | 1 | - | 1 |

| West Virginia | 1 | - | - | - |

| Wisconsin | 1 | 1* | - | - |

| Wyoming | - | 1 | - | - |

| TOTAL | 26 | 37 | 3 | 2 |

|

*Requested interview in lieu of completing online survey. Bold face denotes OT NEPA Assign ment states |

||||

Twelve responses were received from eight private-sector consulting firms and one additional local government official.5 Of these 12 responses, two respondents requested to participate in an interview rather than complete the online survey. Appendix B contains copies of the results of the state of practice online survey sent to organizations and private-sector consultants.

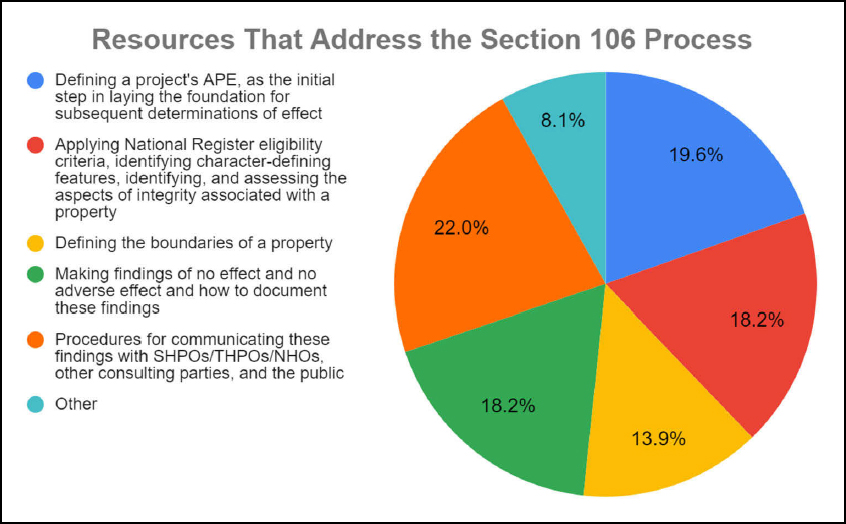

Resources

Survey respondents were asked if the agency/organization they work for has any manuals, guidance, policies, forms, tools, or similar materials that address certain aspects of the Section 106 process, such as defining a project APE, applying NRHP criteria for evaluation (including reevaluation of listings and eligibility determinations), defining boundaries of a historic property, making findings of effect, and communicating with consulting parties about Section 106 decisions and findings. Respondents were then asked if they could provide access to these materials. The survey also included questions about APEs, applying NRHP criteria, and defining property boundaries because these factors play a role in decision-making related to findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect. The survey also included questions about making findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect and communication of these findings to appropriate parties.

Ninety-six percent of the respondents reported having at least some specific resources for the above discussed aspects of the Section 106 process (Figure 4). Two agencies used federal guidelines. One SHPO reported providing guidance on defining the boundaries of a historic property, making findings of No Effect/No Adverse Effect, and communicating findings with SHPOs/THPOs, other consulting parties, and the public during annual training and guidance published jointly with the state DOT.

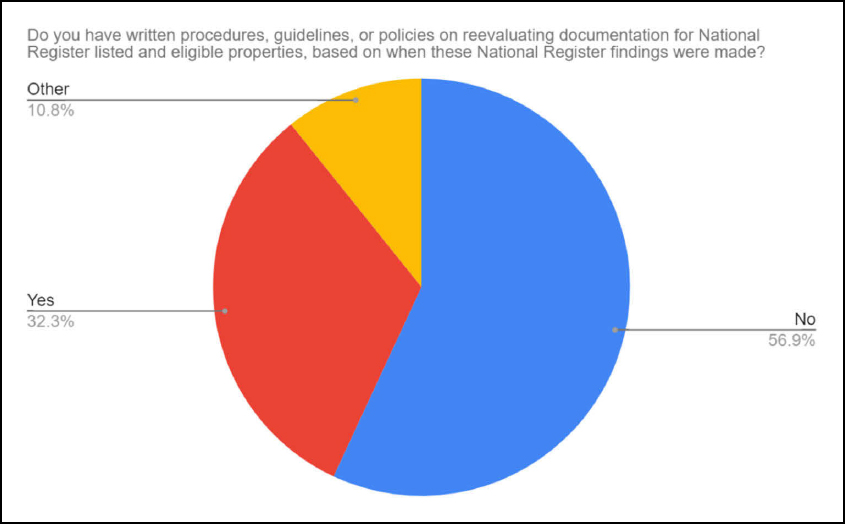

Almost 57 percent of agencies do not have written procedures, guidelines, or policies on reevaluating documentation for NRHP-listed and eligible properties, based on when the initial findings were made (Figure 5). One SHPO addresses reevaluation on a project-by-project basis but also has a general rough guide of five years for reevaluation to conduct “a closer examination…to see if there have been significant alterations made or new historic associations identified.” One state DOT representative reported using SHPO’s reevaluation guidance.

___________________

5 Of the 12 responses from consulting firms, three of the responses came from the same firm. One local government responded to the consultant survey rather than the agency survey.

Practices and Approaches

To understand the current state of practice in making and reviewing findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect, the online survey contained a series of questions on the following topics.

- Have you applied indirect/cumulative effects to your determinations of No Effect or No Adverse Effect? What challenges did you experience in making/reviewing these determinations?

- What are the elements needed in making a well-reasoned and defensible finding of No Effect and No Adverse Effect?

Indirect and Cumulative Effects

Questions were directed to agencies and consultants regarding the application of indirect and cumulative effects. The survey did not define “indirect” or “cumulative” and instead let respondents use their own definitions in responding to the questions.

Eighty percent of agencies and consultants who completed the online survey applied indirect effects to findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect. Fifty-eight percent of the same respondents applied cumulative effects to the same findings. Although most had experience identifying indirect and cumulative effects, many struggled with these assessments for a variety of reasons, including the following.

- Lack of understanding of the ACHP policy on indirect effects.

- Lack of understanding by clients or the public on indirect and cumulative effects.

- Determining how far back cumulative effects should be considered.

- Determining the “tipping point” to reach a cumulative Adverse Effect.

- Assessing indirect effects on historic properties.

Understanding/Use of June 7, 2019, ACHP Memorandum on Direct Effects

The June 7, 2019, ACHP memorandum addresses a court decision regarding the meaning of “direct” in both Sections 106 and 110(f) of the NHPA in the context of Adverse Effects on a National Historic Landmark (NHL) (ACHP 2019a). The memorandum states that the court decision “clarifies how effects in the Section 106 process may be defined as direct and indirect. Importantly, for both Section 106 and Section 110(f), the court recognized that visual effects on historic properties can be direct effects under NHPA.” The memorandum goes on to state that although the court’s decision does not affect the application of Section 106, the decision does instruct how effects should be categorized in the Section 106 review process.

Review of the answers to the question “What challenges if any, have you experienced in making or reviewing direct vs. indirect and cumulative effects?” indicates that only three respondents define noise, visual, and auditory effects as “indirect effects.” In addition, the lack of understanding of how the ACHP (2019a) memorandum should be taken into account in terms of multiple aspects of the Section 106 review process was reported by respondents as a challenge. Respondents provided comments on the specifics of these challenges, quoted below.

- “Inconsistent federal guidance among agencies about what constitutes a direct or indirect effect (for example - FHWA considers viewshed, noise effects, etc. as direct effects, but the USACE [U.S. Army Corps of Engineers] considers them indirect effects). No 106-specific definitions or examples of indirect effects or cumulative effects - usually end up using the NEPA] definition and adapting it to a 106 context.” Consultant

- “Well, there is disagreement among ACHP and other agencies as to what ‘indirect’ vs. ‘direct’ actually means; cumulative effects criteria are VERY vague.” State DOT Representative

- “The client doesn’t understand cumulative effects and different opinions on what is indirect and what is cumulative, even with the SHPO reviewers or State DOT reviewers.” Consultant

- “That most [of] the consultants and agencies do not know how [to] handle indirect and cumulative effects and still are in the mindset that visual effects are indirect, even though they are not.” SHPO Representative

- “The challenge is not in making the finding, but in communicating it to the project proponent in terms they understand.” SHPO Representative

- “That the designers really don’t understand the process and what it means.” SHPO Representative

- “Ensuring the engineers and public understand the difference. Extremely far-removed visual effects. Past effects and how they play into current undertakings.” State DOT Representative

- “Just getting folks to understand how these may apply—there have been very few indirect and cumulative findings. Typically, only for EIS or EA projects.” State DOT Representative

Reasonably Foreseeable and Cumulative Effects

Many respondents also identified challenges with making/reviewing reasonably foreseeable and cumulative effects.

- “With indirect and cumulative, I struggle with finding that ‘enough’ point: ‘you’ve projected effects long enough into the future’ or ‘you’ve looked far enough out from the project’ or ‘you’ve considered enough scenarios/factors.’ It’s not that I’m interested in just checking that box off so ‘tell me what I need to do.’ It’s more about struggling to determine that I’ve really considered these future unknowns well enough. Should I include the potential for alien invasion? (an exaggeration, but it speaks to my point).” Consultant

- “One issue that has come up is if effects that have occurred to a property prior to NHPA and NEPA ever existing (60+ years ago) should be considered as part of cumulative. And if so, how far back should we consider effects - 100 years ago, 200 years ago?” State DOT Representative

- “One of the biggest challenges is determining for cumulative effects is what is the proverbial straw. The initial construction is often the biggest impact, and are later, relatively small changes (in comparison) really changing the conditions much?” State DOT Representative

- “Cumulative effects are very challenging, because they can be nearly impossible to quantify, particularly if my agency is making changes to a setting or landscape that has already been altered by others (i.e. my agency is giving money to a local government for streetscape improvements, but that local government has already constructed a project or two to modernize elements of a historic streetscape). At what point is the work a cumulative adverse effect, and who gets left holding that bag? At what point is it death by a thousand cuts? How do you quantify whether moving heavy truck traffic off a historic main street will result in an economic loss and business closures, versus perhaps creating a safer, ultimately more walkable, attractive, and vibrant downtown because heavy traffic has been moved? Unless we know of actual upcoming future projects, it can be hard to imagine potential future scenarios and then determine with any degree of accuracy if those scenarios could have a cumulative adverse effect.” State DOT Representative

- “Many consultants and federal agency staff do not look beyond physically direct and viewshed analyses of effects. It is hard to get buy-in for indirect and cumulative effects since they are more abstract/not as obvious. It is also hard when it is a larger project that multiple federal agencies are involved with. We have reasonable cumulative effects because there are multiple parts to the larger undertaking, but federal agencies will often only consider their portion of the larger undertaking, but without their portion the project as a whole would not be all that feasible or their portion of the undertaking is directly causing or caused by another portion.” SHPO Representative

- “Developing cumulative effects is much more laborious on our and FHWA’s part. How far or wide do you cast the net in identifying projects? How far back in time does one go? Plus, I thought we were guided in the concept that you can’t have cumulative effects if your project does not adversely affect a resource.” State DOT Representative

- “It’s harder to engage other agencies/project team members to thoroughly evaluate non-physical, reasonably foreseeable, and cumulative effects. Public input tends to recognize the potential for these more readily.” SHPO Representative

Assessing Indirect and Cumulative Effects on Types of Historic Properties and Associated Aspects of Integrity

Many respondents expressed difficulties in gauging the severity of indirect effects that may occur later in time or are farther removed in distance from an undertaking.

- “The aspects of integrity most often indirectly affected by projects (setting, feeling and association) are more subjective and intangible than effects to materials, workmanship, and design. Cumulative effects are always a challenge; there are no guarantees that any action will have a definitive and quantifiable reaction. We also struggle with cumulative effects from HOP [highway occupancy permit] permits; what’s our APE? How do we ignore development project’s effects to historic resources when the HOP permit is part of what makes the project successful?” State DOT Representative

- “We most commonly discuss cumulative effects for linear archaeological sites, where we need to do a high-level evaluation of the whole site to argue if the current impact contributes to a cumulative effect. We will rarely evaluate indirect effects in a formal way, and it is not part of our standard surveys. So, if indirect effects may be an issue with a resource, we need to think of that early in the project so those data points can be included in the survey [scope of work] or have later field visits to gather the data.” State DOT Representative

- “The severity of indirect effects is harder to gauge, and it can be more difficult to relate the impacts of the indirect effect to specific areas of integrity.” SHPO Representative

- “Defining and identifying what indirect and cumulative effects are, and the effects they can have on different types of historic properties.” SHPO Representative

- “Providing convincing evidence over time that destruction or demolition of a type of resource constitutes as a cumulative effect, particularly with historic bridge replacements. Also, buy-in from upper management.” State DOT Representative

Findings of No Effect/No Adverse Effect

Elements of a Well-Reasoned/Defensible Finding of No Effect or No Adverse Effect

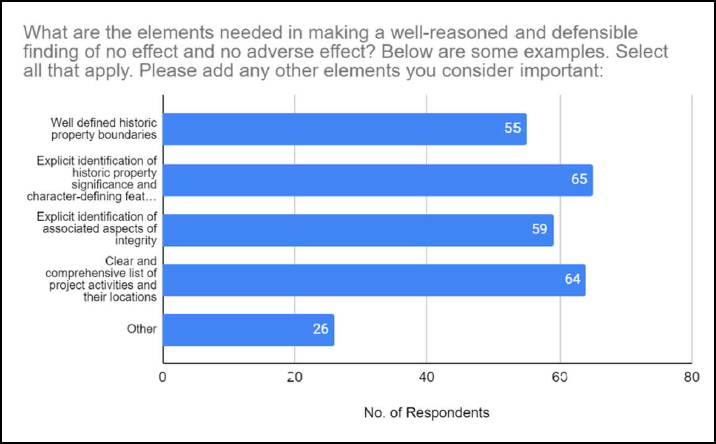

Over half of the respondents considered well-defined historic boundaries, explicit identification of historic property significance and CDFs, explicit identification of associated aspects of integrity, and a clear and comprehensive list of project activities and their locations as-needed elements of a well-reasoned and defensible finding of No Effect or No Adverse Effect (Figure 6).

Below is a sample of survey responses on elements of a well-reasoned assessment of No Effect or No Adverse Effect findings.

Significance and Character-defining Features

- “Local and/or descendant communities’ interpretations of significance and the property’s role to them.” Consultant

- “More general understanding of the overall significance of the property to scholarly or local communities is always helpful.” Consultant

- “Complete identification of CDFs, especially related to landscape, biota, and atmosphere.” Consultant

- “CDFs may not be necessary, but identification of contributing and non-contributing features may be critical. For example, CDFs might be important for a bridge rehab project but overkill for another type of project’s impacts.” SHPO Representative

- “Clear explanation of eligiblity or non eligible. No cut and paste.” SHPO Representative

- “For archaeological properties, an understanding of if ‘marginal’ deposits, i.e., low density/party disturbed deposits, contribute to significance.” State DOT Representative

- “Any applicable replanting or rebuilding necessary to get to a No Adverse Effect. Any landscape changes that may impact the CDFs (setting, location, design).” SHPO Representative

- “For long, linear projects, we routinely consider only if portions of the archaeological site within the APE contribute or not to the eligibility of the overall site. Built environment resources are almost always considered as a whole, even if they extend outside of the APE.” State DOT Representative

- “The resource is not part of a larger district or other cultural landscape or TCP [tradition cultural property].” State DOT Representative

- “Complete land use history.” SHPO Representative

- “Historic context (this may be covered under [historic property significance] but it is extremely important).” FHWA Division Office

- “Identification of specific historic elements within the property boundaries. For example, is the stone retaining wall significant or not? Sometimes the history of the roadway/transportation feature can be important. For example, if the road width has changed significantly over time, that can be an important part of an effect determination.” State DOT Representative

- “Knowledge of what aspects are important in the community.” Consultant

- “TxDOT published studies and regulations.” Consultant

Visual and Noise Effects

- “Understanding of visual and noise impacts generated by project - so noise analyses and visualizations to study and analyze these impacts. I think a set of at least 30% plans is important in addition to a list of project activities to understand and analyze impacts.” State DOT Representative

- “Visual and noise assessments, traffic analysis.” State DOT Representative

- “Address setting, including current/historic noise levels.” SHPO Representative

Direct, Indirect, and Cumulative Effects

- “Clear communication and outreach with descendant communities, and incorporation of their perspective on identification, integrity, effects.” Consultant

- “Depending on the scope of work, an understanding of ways the project may have cumulative effects.” State DOT Representative

- “At times, thinking broader than hard data is important. For example, a property only eligible for architecture can still result in effects or even adverse effects with adjacent changes, even if no physical impacts are proposed.” SHPO Representative

- “Measures to minimize/avoid effects that are part of the project design.” State DOT Representative

- “Locations of and extent of direct effects such as easements, ROW acquisitions.” State DOT Representative

- “[O]ften we need a good understanding of the amount of new ROW to be acquired at the historic property location, depending on the type of project activity.” State DOT Representative

- “Consideration of indirect effects (e.g. new interchange = commercial development).” SHPO Representative

- “Also a well-defined APE that considers direct and indirect impacts based on knowledge of all project-related activities, including any off-site mitigation, water quality/drainage improvements, noise impacts that trigger analyses (i.e., level 1), etc.” State DOT Representative

- “Full consideration of both indirect and direct effects.” SHPO Representative

- “If the finding is ‘No Adverse Effect,’ explaining why - how do the listed items intersect when evaluating the criteria of adverse effect.” SHPO Representative

- “How the undertaking will affect aspects of integrity” SHPO Representative

- “Describing and planning for the worst case scenario.” State DOT Representative

Supporting Documentation/Exhibits

- “The project design – to us, all of the above is valuable but needs to be understood vis-a-vis the project impacts.” State DOT Representative

- “Good photographs (so important, and of more than just the primary facade).” SHPO Representative

- “A variety of attachments that help visually explain the nature of the project activities and their proximity to resources, such as project construction plans, drawings and exhibits, maps, photographs, and mock-ups.” State DOT Representative

- “Sufficient supporting documentation - photos, maps, plans, etc.” SHPO Representative

Consulting Parties/Consultation

- “Understanding of existing agreement documents between the agency and SHPO that govern Section 106 procedures for that particular agency.” SHPO Representative

- “Early consultation to identify consulting parties and their respective responsibilites.” SHPO Representative

- “Input from the Section 106 Consulting Parties.” State DOT Representative

- “Input from CLG [certified local government].” SHPO Representative

Completeness and Quality of Identification of Historic Properties and Documentation of Findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect

Several agency respondents reported that the completeness and quality of work from consultants can vary. Most state DOT respondents reported having established relationships with consultants who generally do quality work. These same respondents reported that consultants who do not often work for them require more review. Some state DOTs have consultant qualification training courses to ensure that consultants are qualified to provide the information a state DOT needs. Many state DOT respondents stated that they do not allow consultants to make recommendations on effects, reserving that task for in-house state DOT staff. Common issues respondents reported that affect quality and completeness of identifying historic properties and documenting findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect include the following, listed in order from most common to least common.

- Less competency in assessing effects.

- Issues with quality and completeness of work products.

- Consultants not well trained in Section 106.

- Built environment evaluations being done by archaeologists.

Experiences

Findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect

Survey respondents were asked to identify challenges in making or reviewing findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect for certain types of transportation projects (e.g., bridge replacements, rural capacity projects). Some project types that were cited include the following.

- Projects involving linear resources, such as railroads and irrigation ditches.

- Road widening and realignment projects.

- Transportation notification systems (pole-mounted cameras, gantries, etc. placed within or adjacent to existing highways).

- Streetscape, pedestrian safety, and micro mobility improvements.

- Projects involving rural historic districts.

- Bridge replacement and rehabilitation.

- Projects involving historic roads/historic road corridors.

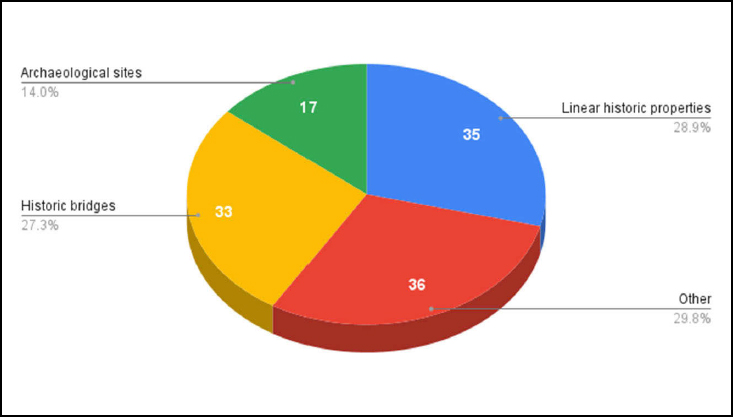

Survey respondents were asked a similar question regarding whether certain property types presented challenges when making or reviewing findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect. Fifty-two out of 64 respondents experienced challenges in making these findings for certain property types. Historic bridges, linear historic properties, and “other” types of properties are listed as the most common property types that presented challenges (Figure 7).

Many of the comments regarding linear historic properties describe the difficulty of assessing effects of projects along historic roadways. Similar challenges were expressed regarding historic districts.

- “Many projects that convert intersections along historic roadways that are considered NRHP-eligible from traditional designs to roundabouts are considered to have No Adverse Effect. When reviewing projects independently of one another, this seems true, however, it appears that eventually a tipping point will be reached where enough intersections have been converted that a design element of the historic roadway will have been lost without ever having been considered an adverse effect. This issue also appears in projects that propose to add sidewalks along segments [of] NRHP-eligible roadways where the rural shoulder is considered a contributing element.” SHPO Representative

- “Road widening projects and introduction of new lanes and how that practice overtime can adversely affect the historic road (cumulative).” SHPO Representative

- “Also, it’s challenging to evaluate effects to linear resources, such as railroads or irrigation ditches, where we may determine the entire resource is significant, but we’re just looking at the segment in our project area for integrity and as the basis for evaluating effects to the ENTIRE resources.” State DOT Representative

- “One challenge [our agency] regularly faces is replacement of small bridges in large rural historic districts. What makes a state standard bridge with no distinguishing design features or use of local materials contribute to, for instance, an agricultural historic district? Is it the location and presence of a crossing, allowing farmers to get their products to markets, which contributes to the district’s significance? Or is it the physical bridge itself? If it’s the former, then is its replacement with a bridge of similar size and scale adverse? If it’s the latter and it is being replaced with a similar bridge, then is it adverse? Is there a standard design that could be used in these situations to either avoid or mitigate for an adverse effect?” State DOT Representative

Linear resources, such as historic roadways, and historic districts also pose challenges when assessing effects resulting from streetscape, pedestrian safety, and mobility improvement projects. These improvements can change historic elements such as street trees, building setbacks, lawns and landscaping, and historic materials such as brick and stone sidewalks, historic street signs and lighting, and other small-scale features that can be contributing elements of the district or linear resource. Several

respondents raised concerns on assessing the effect of relatively isolated/small-scale projects on larger historic districts.

- “No Adverse Effect - for example - The project will remove 1 historic era lamppost. Remaining 23 contiguous lampposts are protected from harm. The one to be removed is located immediately adjacent to existing intersection to be improved (at the end of the series of 23). Measures to avoid any additional impacts to contributing features have been included in design. The eligible district was identified as part of [the DOT’s] review of the project (through ‘good faith effort’) and notified project team early to ensure measures to avoid/minimize were included in design. The SHPO views 36 CFR § 800.5(a) and removal of a contributing feature (even if just one of a series) as adverse effect. Our view is that the context and intensity of the undertaking must be considered and whether the federal action diminishes the significance of the resource so that it is no longer eligible for inclusion in the NRHP. An adverse effect finding due to the removal of one lamppost would trigger an Individual 4f. In the end, the SHPO concurred with No Adverse Effect.” State DOT Representative

- “We have had challenges on projects that are providing safety improvements in historic districts such as crosswalks, pedestrian refuge islands, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant crossing, etc. Our stance has been that the changes benefit the district and make it safer and do not alter the CDFs to the point of jeopardizing integrity or eligibility and therefore, have No Adverse Effect. The SHPO has argued that we are changing the way the historic district looks and therefore, it is an adverse effect.” State DOT Representative

Several respondents also stated that their biggest challenge was establishing an appropriate APE and level of effort for identification that was commensurate with the undertaking.

- “We also struggle with what is the appropriate level of effort to identify what might be a very large rural historic district when the project involves an online replacement of a culvert with minimal ROW acquisitions in the surrounding quadrants. What identification of resources is commensurate with such a small scope of work?” State DOT Representative

- “Properly defining APE for projects that generate foreseeable associated development.” SHPO Representative

Findings of No Adverse Effect with Conditions

Respondents were asked if they had experience in making or reviewing the application and interpretation of the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties in the context of findings of No Adverse Effect such as for findings of No Adverse Effect with the imposition of conditions on a project.

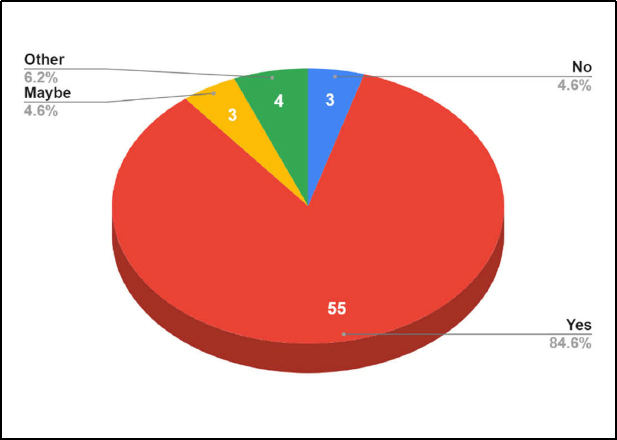

- Fifty-five of 65 agency respondents reported experience with findings of No Adverse Effect through the use of conditions (Figure 8). Only four of 12 consultants reported experience working with No Adverse Effects with the use of conditions. A few agencies stated that they no longer apply conditions to No Adverse Effects, and these are quoted below. “Technically we cannot have NAE with conditions—at least that is what the ACHP training states.” SHPO Representative

- “We no longer use No Adverse Effect with conditions findings. Instead, these types of evaluations would likely result in an adverse effect finding, recognizing minimization efforts which sometimes can contribute to mitigation.” SHPO Representative

Consultation and Communication

The online survey asked a series of questions to understand the successes and challenges of consulting and communicating with partner agencies and the public for projects with findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect.

- Have you had experience with disagreements or disputes on No Effect and No Adverse Effect findings? (Yes/No/Other).

- □ If “Yes” what was the substantive nature of any disagreement?

- What successes/challenges have you experienced in documenting and communicating No Effect and No Adverse Effect findings to the public?

- What successes/challenges have you experienced in consulting with consulting parties such as national preservation organizations and state and local preservation organizations (e.g., state, and local historical societies and commissions) in making findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect?

- In your experience, what are some of the best approaches for establishing and maintaining positive relationships among the transportation agencies and consulting parties in the context of the No Effect and No Adverse Effect determination process?

Disagreements on Findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect

Sixty-six percent of respondents had some experience with disagreements or dispute on findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect, and the elements used in making an effects assessment. Twenty-six of these respondents were state DOTs, 22 were SHPOs, six were consultants, two were FHWA Division Officers, and one was an FPO. The most commonly stated reasons for these disputes included the following, in order from most common to least common.

- Level of effect.

- Eligibility findings.

- Definition of the APE.

- Integrity.

- Noise effects.

- Visual impacts.

Information provided by respondents on disputes indicates that most disagreements were between SHPOs and state DOTs. Three of these disagreements between a SHPO and state DOT were submitted to the ACHP for review. Three other dispute resolutions conducted by the ACHP involved disputes between property owners and SHPO, a state DOT and another agency, and a state DOT and a consulting party.

Successes and Challenges Documenting and Communicating Findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect to the Public

Several respondents indicated that findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect are not communicated to the general public for various reasons: not enough time, no public interest in non-controversial projects, and lack of understanding of the process by the public. When engaging the public on these findings, several respondents indicated that the public’s lack of understanding of the Section 106 process hampers attempts to communicate with the public.

Some respondents cited a variety of different ways in which information on these findings can be communicated to the public.

- Public outreach program or dedicated public outreach officer.

- Project websites.

- Statewide project/undertaking websites.

- Public meetings.

- NEPA public outreach.

Several respondents commented on the importance of communication on these findings.

- “If we can show how we have avoided or minimized effects that is usually a more positive conversation than talking about the categories of effects.” State DOT Representative

- “The locals/project sponsors are learning that [public involvement] is a critical component to achieving SHPO concurrence and ensuring the project takes into consideration effects on historic properties.” State DOT Representative

- [Our state] has an online posting system that is very successful in sharing all our Section 106 documentation with the public. It allows us to increase our transparency, easily share documents with CPs [consulting parties] and other interested parties and helps engage groups and individuals.” State DOT Representative

Successes and Challenges Consulting with National Preservation Organizations and State and Local Preservation Organizations

Respondents provided a number of comments on how consulting with CPs such as national preservation organizations and state and local preservation organizations (e.g., state and local historical societies and commissions) was beneficial to the process and the outcome of findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect.

- “We have had success with local historical societies. They seem to understand the broader context of these kinds of consultations and typically try to be collaborative partners in the solution, rather than pointing out problems.” Consultant

- “Consensus from these types of groups really helps with SHPO consultation and SHPO concurrence.” State DOT Representative

- “If projects are not controversial, bringing them in early and making sure their concerns are heard they can become - if not advocates - at least more trusted parties to relay information.” State DOT Representative

- “Local preservation groups can provide essential information regarding a property’s history. Often, everything is significant or eligible, but if a group feels that a particular resource is identified and addressed, even if it is decided not to be eligible, things typically go smoothly.” State DOT Representative

- “By working with a local historical society, we were able to identify an unmarked enslaved cemetery early in project planning and shift the road widening south to avoid effects on the cemetery.” Consultant

- “Open discussion and compromise have successfully avoided adverse effect determinations for several projects and resulted in No Adverse Effect determinations.” State DOT Representative

- “With local organizations, we have found that once extra explanation is provided about the nature of the effect and the regulatory framework there is agreement.” State DOT Representative

- “CPs can be helpful in prioritizing what is most important for them in terms of minimizing adverse effects or in terms of mitigation results.” State DOT Representative

- “They often provide greater context for the establishment of the significance of a resource.” SHPO Representative

- “Typically, the preservation minded organizations that are involved here are looking out for the best interests of their town, and they add great background information for the project. They tend to be happy when you aren’t impacting their resources.” State DOT Representative

Although some respondents expressed the benefits of national and local consulting party participation, respondents also identified several challenges when working with these groups. Some point to the lack of understanding these groups have of the Section 106 process, which hinders meaningful participation. Respondents also report difficulty in getting consulting party participation for projects that do not pose a threat to historic properties, which is typical of findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect. Additional comments on the challenges of working with these groups are provided below.

- “We don’t get a lot of consulting party feedback but when we do, it is typically because they don’t agree with either how we have identified the property or with effects. There’s a disconnect in general because Section 106 is pretty academic, and I don’t think CPs always understand what we’re asking for and then they don’t understand how we evaluate resources. We have developed a section on our web site for CPs so they understand what we’re asking for and how they can participate, and we include the link to this information in all our letters to CPs.” State DOT Representative

- “Consultant/transportation not leading the discussion effectively. Consultant/transportation not being prepared with all the project info. CPs not knowing the 106 process - learning curve. CPs having different viewpoints as to mitigation, whether there is an effect, minimization measures, etc.” SHPO Representative

- “Many times, the challenges can be getting the parties to comment or to speak with one another and come to an agreement on their stance, rather than having several people speaking ‘on behalf’ of a certain group.” SHPO Representative

- “They don’t know they have a voice in the process.” SHPO Representative

- “Lack of response in timely manner. FINDING the appropriate folks to consult with. Would be nice to be able to use more social media but we are very limited in that as a DOT. DOT feels need to be very controlling on that platform.” State DOT Representative

- “Engaging local preservation organizations is sometimes challenging. Their focus is not always on the types of resources involved in our projects, or they don’t have the staff/volunteers able to devote their time to the CP process. National preservation organizations sometimes lack the local perspective on needs and what communities value, which can lead to people talking past each other or bristling when there’s disagreement. Locals, including the project team members, often question the validity of a national organization’s perspective and their right to be at the table.” State DOT Representative

Best Approaches for Establishing and Maintaining Positive Relationships Among the Transportation Agencies and CPs

A majority of agency and consultant respondents cited early consultation and regular communication with agencies and CPs as best practices for establishing and maintaining positive relationships among these parties. Some respondents stressed the use of all forms of communication with agencies and CPs (telephone calls, meetings, emails, messaging, social media). Respondents also cited being transparent and consistent in communications to build and maintain trust. Respondents report that regular and open communication among state DOT and SHPO staff allows members to “get ahead of the issues,” as one SHPO Representative expressed it. Several state DOT respondents reported having regular meetings with the FHWA, SHPO, and CPs to discuss issues and review projects. Several consultants provided comments on the importance of completeness and quality of reports and early communication of results to agencies.

- “Producing quality, in-depth reports show a technical competence and establishes a mutual respect in the process.” Consultant

- “Early communication about potential eligible properties and districts and the impact the project would have on them.” Consultant

Consideration of Effects During Project Planning

Participants were asked a series of questions regarding consideration of effects during project planning, including long-range planning, a 10-year planning horizon, a five-year planning horizon, and projects included in the State Transportation Improvement Plan (STIP).

- Does your agency consider effects to historic properties during early project planning to avoid or minimize potential effects?

- At what stage in the early planning process does your agency consider effects to historic properties to avoid or minimize potential effects?

- At what stage in the early planning process are SHPOs, Tribes, NHOs, and other CPs involved in terms of the consideration of potential effects to historic properties?

- Is there a reason why your agency does not consider these potential effects in these early planning efforts?

- How are the SHPO and other CPs involved in these early planning efforts?

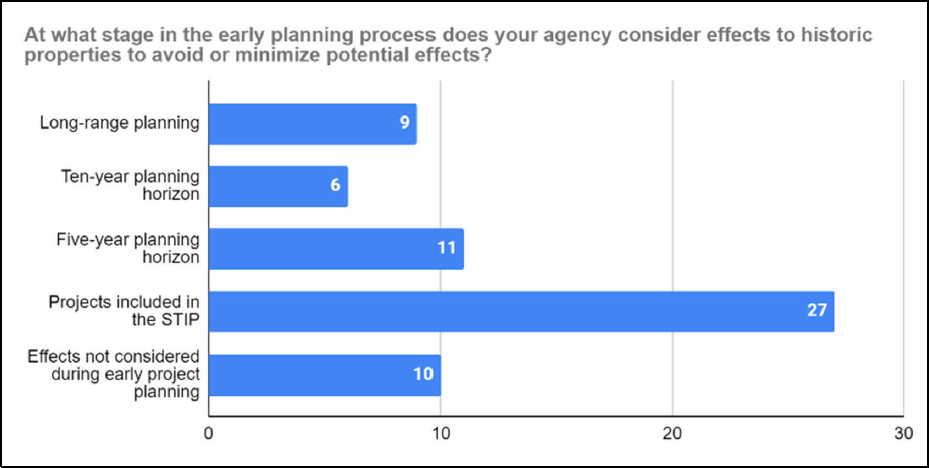

One FPO, one FHWA Division Office, and 29 of the 35 state DOTs that responded indicated that they did consider effects to historic properties during early project planning to avoid or minimize potential effects. Most agencies reported that they consider effects to historic properties when projects are included in the

STIP (Figure 9). Almost an equal number of respondents reported considering effects to historic properties in long-range, 10-year, and five-year planning horizons combined.

When engaging SHPOs, Tribes, NHOs, and other CPs, responding agencies again favored when projects are included in the STIP as the appropriate time for engagement. These results may not reflect actual practice, however, as many state DOTs did not respond to this question. Six respondents indicated that they do not reach out to CPs until a project has been initiated or even until after cultural resource surveys are complete.

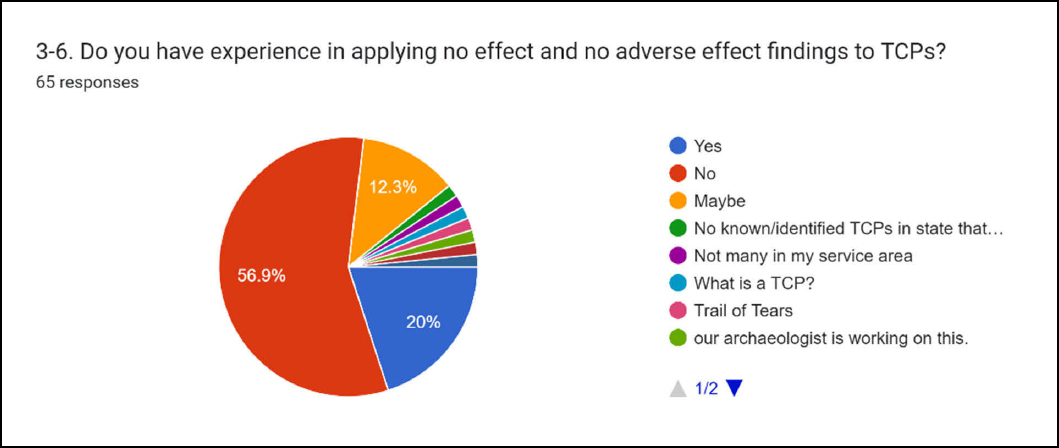

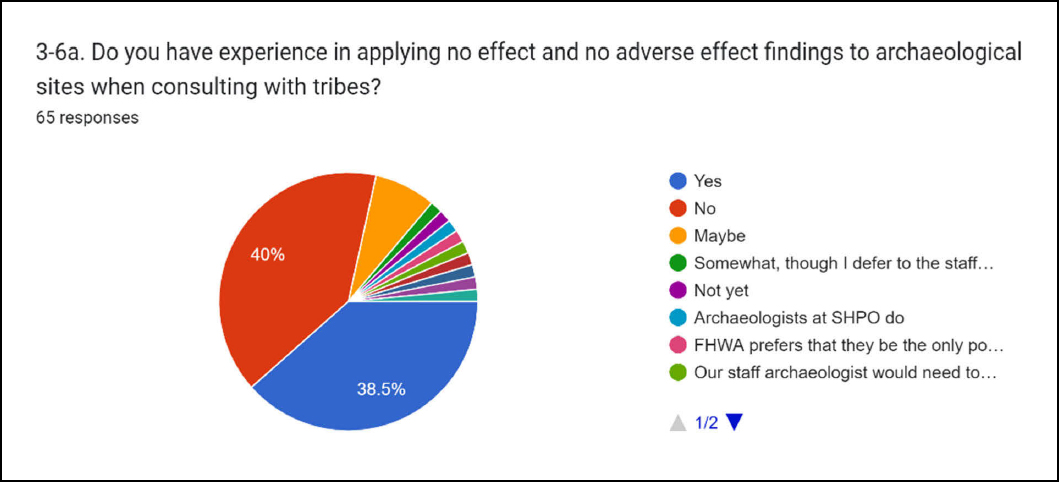

Archaeological Sites and Traditional Cultural Properties/Places (TCPs)

Two questions asked about respondents’ experience with findings of No Effect and No Adverse Effect for archaeological sites and TCPs. Most respondents reported lacking experience making these findings in association with these types of resources and places. Twenty percent of respondents reported having experiences with TCPs, and 38.5 percent had experience with archaeological sites (Figures 10 and 11); however, it was not clear if these rates were low because the respondents had little or no experience given their role within the agency or firm, these effect findings were seldom applied to archaeological sites or TCPs, or other reasons. Two respondents stated that although they did not have such experience, archaeologists on their staff might. As a result, the project team used the interviews (see following chapter) as a way to expand on the limited online survey responses.

Few verbal additional comments were submitted in response to these questions, beyond those explaining why the respondent had no relevant experience. One respondent did note that when it comes to archaeological sites, there is either No Adverse Effect finding or an Adverse Effect finding followed by archaeological data recovery to resolve the Adverse Effect.

ONLINE SURVEY RESULTS (THPOs)

Thirteen responses were received from THPOs (Table 3). Of these 13 responses, one respondent requested to participate in an interview rather than complete the online survey (identified with an asterisk in Table 3). Copies of the results of the state of practice survey sent to THPOs are provided in Appendix C.

Tribal Consultation and Engagement

THPOs were asked the following questions.

- When the agencies are assessing the effects of their projects on archaeological sites and places of religious and cultural significance to your Tribe, has your consultation with FHWA and state DOTs been a positive and constructive experience?

- If yes, what made it a positive and constructive experience?

TABLE 3: TOTAL STATE OF PRACTICE SURVEY RESPONDENTS BY THPOS

| NATION |

|---|

| Oneida Nation of Wisconsin |

| Tohono O’odham Nation |

| Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians |

| Fort Independence Indian Community of Paiute Indians* |

| Squaxin Island Tribe |

| Omaha Tribe of Nebraska |

| Forest County Potawatomi Community |

| Chemehuevi Indian Tribe of the Chemehuevi Reservation, California |

| Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma |

| Hualapai Tribe |

| Miami Tribe of Oklahoma |

| Northern Cheyenne Tribe |

| Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Chippewa Indians* |

| TOTAL =13 |

- How often do these agencies consider the expertise of your Tribe in making No Effect and No Adverse Effect determinations?

- How do agencies consider your Tribe’s expertise in making No Effect and No Adverse Effect determinations?

- When do agencies reach out to your Tribe for expertise?

- If an FHWA and state DOT project touches a place of religious and cultural significance to the Tribe, or if the place is visible from the project area, has the Tribe ever agreed that the project would not affect or have No Adverse Effect on this place?

- Does the type of project influence this decision?

- Have you experienced challenges in consulting on No Effect and No Adverse Effect findings with the FHWA and state DOTs?

- If yes, please discuss the challenges below:

- Have you had experiences with disagreements or disputes on No Effect or No Adverse Effect findings?

- If “Yes” what was the substantive nature of any disagreement?

- In your experience, what are some of the best approaches for establishing and maintaining positive relationships among the transportation agencies and Tribes in the context of the No Effect and No Adverse Effect determination process?

- Do you have specific projects or case studies that you can share with us that exemplify successful and challenging determinations of No Effect and No Adverse Effect?

Some respondents reported that whether they were included in the process seemed to depend on the whims of the agencies and the consultants, and that they were often considered an extra burden rather than an integral part of the process.

Answers to the question, “When the agencies are assessing the effects of their projects on archaeological sites and places of religious and cultural significance to your Tribe, has your consultation with FHWA and state DOTs been a positive and constructive experience?” were as follows.

- “It depends on who the contractors are.”

- “Considered more of an obstacle than a safeguard to protect these sites.”

- “When it benefits the organizations and their projects, my opinion is valuable.”

- “Often, Tribal expertise is considered an afterthought in the process of considering No Effect and adverse effect determinations.”

As far as what made the process work better, respondents emphasized bringing them into the process early and treating them with respect.

- “Bring tribes into the planning process earlier.”

- “The best approaches have been to approach Tribes earlier in the process than some projects in the past have. This allows time for Tribes to prepare information and, should the need arise, to communicate internally to all the departments and individuals involved in the process.”

- “Tribes need to be consulted years in advance of some projects and we need to be viewed in the same way as SHPOs.”

One respondent summed up the benefits of consulting early and often.

- “[The state DOT] generally ask for concurrence on all the major NHPA steps (APE, need for additional work, Determination of effect/s, etc.). By the time they make a determination of No Effect, they pretty much already have concurrence from all parties.”

Other respondents wrote that frequent, face-to-face meetings made the process much smoother.

- “Communication. Regular meetings (we have monthly) to discuss projects.”

- “Building lasting personal relationships has been the best and almost foolproof way to preventing problems with the determination process. Actually, meeting and interacting in non Section 106 settings is the best way for Section 106 to succeed.”

On the specific issue of findings of No Adverse Effect, some respondents thought that not enough work had been done to rule out cultural remains such as burials stretching well beyond the known boundaries of a site.

- “Also, the boundaries from which the minimum approaching distance has been set. How would any of us know how far out our ancestors are/can be buried? This can also be a part of an entire district and or cultural landscape containing burials for specific tribal reasons, as an example.”

One respondent felt that too much work was done in some instances, for example, testing burial mounds rather than accepting tribal views about their nature.