Blueprint for a National Prevention Infrastructure for Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders (2025)

Chapter: 2 The Evidence Base on Programs

2

The Evidence Base on Programs

This report is focused on the infrastructure needed to support the successful adoption and implementation of interventions to prevent mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) disorders and promote well-being. The breadth and quality of preventive interventions for MEB disorders are the focus of several National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) reports (for example, NRC and IOM, 2009; NASEM, 2019a,b,c, 2020). As noted in these reports and elsewhere, the evidence base regarding the prevention of MEB disorders is robust in some crucial ways and lacking in others: there are a number of interventions with decades of high-quality research to support their effectiveness, particularly focused on children, youth, and families. However, there are related to gaps in the evidence and the mechanism through which high-quality evidence is disseminated to would-be adopters and implementers. This chapter begins with a brief discussion of the translation pipeline from pre-implementation to implementation studies, followed by discussion of approaches (used interchangeably with “interventions” and “package of interventions”) across settings and stages of the life course and a discussion of the gaps in evidence and research needs related to both intervention research and dissemination and implementation research.

RESEARCH TO TRANSLATION PIPELINE

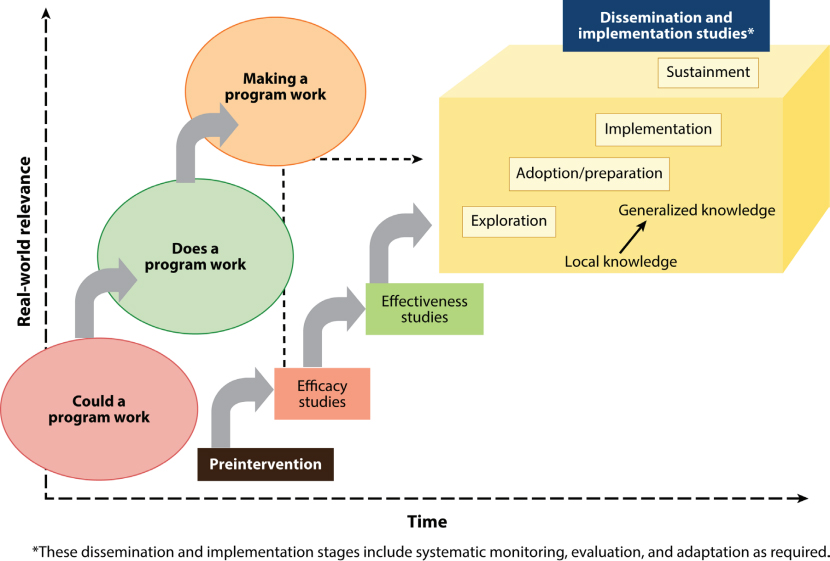

Figure 2-1 illustrates the pipeline from intervention research to implementation research (Brown et al., 2017). Intervention research here also encompasses more foundational questions related to disorder processes, such as pathophysiology, etiology, natural history, and comorbidities. It also encompasses research questions related to

- psychometric properties such as reliability, generalizability, and validity;

- risk assessment and health equity considerations, which includes a wide range of complex risk and protective factors, ranging from individual behaviors or individual biological (including genetic, metabolic, and physiological) risk factors to social drivers of health and lack of fair opportunities to attain one’s full potential for MEB health; and

- intermediate and long-term outcomes, i.e., potential benefits or harms of interventions.

Implementation research encompasses questions about the dissemination and implementation of those interventions: how information about new

SOURCE: Brown et al., 2017. Copyright © 2017 Annual Reviews. CC-BY-SA.

interventions is collected and shared and how interventions can be effectively implemented in real-world settings. This can include research related to the following:

- The effectiveness of evidence-based clearinghouses and improving them, along with other knowledge-sharing resources; and

- Strategies and resources needed to deliver interventions within communities with fidelity and sustainment, including access to and ability to use relevant data, a competent workforce to deliver interventions, and training and other technical support.

It is important to note that this research and practice pipeline is fundamentally a loop, requiring constant feedback to improve research, practice, and ultimately, MEB outcomes—see Smith and colleagues (2024) for another example of the research pipeline. As with a learning health care system, a learning infrastructure focused on prevention of MEB disorders may incorporate data-driven, embedded learning that feeds back into the infrastructure, continuous improvement, collaboration and transparency, and health equity and representativeness. This focus on learning and continuous improvement applies both to the research on interventions and each component of the infrastructure as discussed in each chapter (Abraham et al., 2016; IOM, 2013).

As is discussed in Chapter 1, the committee directed most of its attention to questions related to the infrastructure that would support primary (before MEB disorders occur) and universal (targeted at the entire population) prevention approaches. Primary prevention as used here includes health promotion and consists of approaches to reduce the incidence of MEB disorders and support MEB health (see Figure 2-2 for a visual representation of the spectrum of possible prevention approaches). Secondary and tertiary prevention are grouped together in this report—encompassing approaches to reduce the prevalence of MEB disorders or treatment modalities to prevent relapse. Examples include screenings for depression before clinical MEB symptoms become apparent; medication-assisted treatment for individuals diagnosed with clinical MEB disorders, such as schizophrenia; or lethal means counseling to reduce risk of suicide. Although the committee understood its charge largely to focus on primary prevention, the report touches briefly on secondary and selective interventions—targeted to people or groups with above-average risk, or tertiary and indicated preventive interventions—for people or groups already engaging in high-risk behaviors or experiencing an MEB disorder.

Many preventive interventions have targeted risk and protective factors. The former are characteristics that are associated with negative MEB outcomes. The latter are positive conditions that lower risk factors or prevent negative MEB outcomes. Both can occur in many domains, including

SOURCE: NASEM, 2019a.

individual, family, partner, peer, community, school, and workplace, and intersect in daily life across the entire life course. Risk factors for MEB disorders across the life course include adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), (see Box 2-1), trauma and stress, grief/bereavement, lack of a consistent caring adult during childhood, in utero exposure to maternal stress, racial discrimination, co-occurring psychiatric conditions, adult unemployment,

BOX 2-1

A Note About Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

One crosscutting and multifaceted risk factor for developing an MEB disorder is ACEs, which broadly refers to “childhood exposure to potentially traumatic experience including violence, abuse or neglect, witnessing violence in the home or community or having a family member attempt or die by suicide” (CDC, 2024a). Felitti and colleagues (1998) showed that children with high ACEs scores are far more likely than their peers to face poor health outcomes, including depression, violence, being a victim of violence, and suicide. Phillips and colleagues (2017) suggest that evidence-based home visiting could help prevent the intergenerational transmission of ACEs.

abrupt cessation of pain medication, and bullying. Protective factors include healthy social and emotional development; positive/benevolent childhood experiences; accessible and affordable mental health (MH) care services; building resilience to stress; social support, connectedness, and opportunities for positive socialization; and promotion of parental and family MH (Latimore, 2023; NASEM, 2019a). As illustrated by the socio-ecological framework, risk factors operate at the individual, family, and community levels, as do the social determinants of health (SDOH) that influence them, including economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (see Chapter 7 for a discussion of broader social policies that relate to the SDOH at a more macro level).

Over the last 50 years, the field of prevention science has focused on how best to “promote health and well-being and prevent health conditions from starting or getting worse” (ODP, 2024), drawing from multiple disciplines, including public health, psychology, sociology, and neurobiology. Prevention research explores how biology, behavior, environments, physical and MEB health services and systems, and physical- and MEB-health–related policies can affect physical and MEB health and well-being by identifying risk factors and protective factors to target, developing and evaluating interventions, and developing best practices to disseminate and implement those interventions (NPSC, 2019; ODP, 2024; SPR, 2011).

Much of this research is focused on the beginning of the life course—preconception through young adulthood—and can be found in National Academies reports (see NASEM, 2019a,b,c, 2020) that provide details about healthy development in early life. However, the prevention of MEB disorders and promotion of MEB health can occur later in life as well, which is why this committee also briefly discusses approaches to prevent MEB disorders in adulthood.

PREVENTION APPROACHES

This section offers a brief overview of evidence-based and promising approaches that can prevent MEB disorders and promote MEB health across the life course; it is not a comprehensive review of all relevant interventions, nor does it attempt to assess their reach or impact. As discussed in the introduction, examples of different approaches are used to explore the characteristics of programs that may be delivered within the proposed prevention infrastructure, rather than an endorsement of any particular intervention. Most programs or approaches discussed as exemplars were named in multiple evidence clearinghouses (also referred to as “registries”) for prevention science, healthy youth development, or MEB health promotion and substance use prevention. Some exemplars are newer and may not

be found in any clearinghouses. For newer exemplars that show promise featured in the report, sources are noted.

While many types of approaches are cited in literature as “evidence based,” this report also refers to “practice-based evidence.” In this report, evidence-based programs (EBPs) comprise a rigorous evidence base (often including randomized controlled trials [RCTs]), include considerations for clinical judgment and patient context, and are often considered the “gold standard” for preventive interventions (APA, 2005; NIHB, 2009). Practice-based evidence encompasses interventions that are “derived from, and supportive of, the positive [culture] of the local society and traditions” (NIHB, 2009, p. 10). These categories offer something of a false dichotomy by indicating that interventions can either be rigorously evaluated or culturally appropriate and co-designed with people with lived expertise. However, these concepts need not be mutually exclusive (see “Healing of the Canoe” discussed below for one example). Some examples in this report also highlight what is often called “community-based evidence,” which may lean more heavily on consensus from coalitions and community members (Bartgis, n.d.; Wolfson et al., 2017). Green and Allegrante (2020) outlined three sources of practice-based evidence: participatory research and Practice-Based Research Networks, systems science (helpful in addressing complex problems that affect an entire community), and systematic reviews (which analyze and assemble multiple studies, including practice-based experience).

National Academies reports have provided extensive descriptions of evidence-based interventions (IOM and NRC, 2009; NASEM, 2019a,b,c). In the section that follows, the committee provides a very brief, non-exhaustive overview of some interventions implemented across different settings and for different age groups, and in some cases, for specific groups of people, to underscore that they are one component of the infrastructure and illuminate the infrastructure considerations needed to support the delivery of such a wide range of interventions. This chapter also includes some examples of promising practices that may not have a well-developed evidence base but offer new ideas about preventive interventions among populations or in contexts that are historically lacking (for example, see Box 2-7, a brief review of web-based preventive interventions). The inclusion of a preventive intervention in this chapter is not an endorsement from the committee for its implementation, as this was well outside the committee’s charge. The descriptions are intended to conceptually ground the later chapters on the workforce needed to deliver the interventions; the data needed to select, implement, and evaluate them; the funding needed to support the infrastructure; and the governance and partnerships needed to lead the way in MEB promotion. These examples highlight the considerations needed for a prevention infrastructure to support the delivery of interventions across a variety of settings and life stages, as illustrated by the “exemplar” boxes throughout the other chapters.

The illustrative approaches below are grouped both by settings and/or stage of the life course.

Approaches for Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults

Approaches in Family and Community Settings

Approaches for family and childhood settings include strategies that address parent, family, and other primary caregiver needs to support healthy parenting strategies and home environments, mitigating risk factors and promoting protective factors from conception through young adulthood. As noted in Box 2-2, the Nurse-Family Partnership program targets pre-birth outcomes by addressing risk factors that are associated with poor birth outcomes and continuing the support during the early days of parenting. Group-based parenting interventions can address mental health, particularly depression during pregnancy and postpartum, and prevent substance use disorders (SUDs) and child neglect and abuse. Programs focused particularly on supporting the development of positive parenting skills can also have indirect positive effects on reducing maternal depression and reducing substance and alcohol use (Barlow et al., 2002; Cioffi et al., 2021; Forgatch et al., 2009; Patterson et al., 2010; Shaw et al., 2009).

Overall, the evidence base connects positive MEB outcomes among children and adolescents with interventions that can be tailored to cultural and other community contexts, treat parents as knowledgeable and equal partners in childrearing, integrate services for families with multiple service needs, support peer networks for parents, address trauma among parents, and increase fathers’ involvement in parenting (NASEM, 2019a).

BOX 2-2

Evidence-Based Program: Nurse-Family Partnership

The Nurse-Family Partnership is a home-visiting program that sends registered nurses to visit the families of low-income, first-time mothers from pregnancy through the child’s second birthday. These nurses deliver a strengths-based and trauma-informed program and develop a therapeutic relationship with participants. Child abuse and neglect, arrests, behavioral impairments due to use of alcohol or other drugs, and child mortality are reduced. The results have been sustained over time.

SOURCE: CEBC, 2024.

Approaches in Education-Based Settings

Decades of research supports the use of preventive interventions in school settings, from preschool through college. The committee considered the large base of research of preventive interventions in education settings. For example, socio-emotional learning (SEL) programs have demonstrated effectiveness for improved social skills, MH, prosocial behavior, academic achievement, and the prevention of antisocial behavior and substance misuse. Early childhood education programs are associated with increased educational attainment, consistent employment, and improved self-control and self-esteem. All of these are protective factors to support MEB health and reduced the likelihood of receipt of public assistance, involvement in the criminal legal system, and substance misuse (Latimore, 2023; Reynolds et al., 2011). Many classroom-based programs (including those for adolescents) prevent and reduce disruptive behavior, depression, posttraumatic stress and trauma, substance misuse and SUD, and bullying (NASEM, 2019a). One such example, LifeSkills Training, is a classroom-based universal prevention program designed to address substance use initiation and violence for 12–14-year-olds (Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development, 2024b). Teaching three major skills (personal self-management, social skills, and information and resistance skills) over 3 years, the program has shown to significantly lower rates of polysubstance use at 6.5-year follow-up and violent behavior at posttest and significantly slower growth rates in cigarette initiation and alcohol use at 5.5 years after baseline. Similar types of skills training programs along with brief motivational interviewing programs focused on the risks of alcohol use can reduce problematic use in college students as well, particularly when introduced as a package of multiple interventions (environmental and individual) (NIAAA, 2019a). See Box 2-3 for a description of the Good Behavior Game, which is used in school settings and is part of the U.S. Department of Education evidence clearinghouse.

Out-of-school-time programs can provide similar opportunities as classroom-based programs for children and adolescents. In addition to supporting food security and nutrition education and providing avenues for healthy physical activity, they often offer SEL programs for youth (CDC, 2023; Sparr et al., 2020). Programs that focus on developing interpersonal skills are linked with positive social behavior, another protective factor to support MEB well-being (see Box 2-4 for a promising program) (CDC, 2023).

Healing of the Canoe is one example of PBE specifically developed for tribal youth—an intervention developed in partnership between the Suquamish Tribe, Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, and University of Washington Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute (ADAI) (Healing of the Canoe,

BOX 2-3

Evidence-Based Program: Good Behavior Game

The Good Behavior Game (GBG) is an intervention designed for children grades Pre-K through 6th, delivered by teachers or other adults (parents or school staff). The GBG can be integrated into the school day and involves a set of self-management and self-regulation exercises that can promote healthy social behavior by having children predict good and bad behaviors during transitions between activities. Recipients of the GBG intervention showed reduced drug/alcohol use later in life, reduced conduct problems, and reduced mental health service need.

Teachers can be trained in implementing GBG in the classroom through an initial two-day training, booster training sessions, and GBG coaches. GBG coaches undergo an extra day of training and are audited by the American Institutes for Research on the implementation of GBG in their schools. Coaches can become certified GBG trainers with an additional year of training.

2024). Suquamish and Port Gamble S’Klallam leaders identified community needs to prevent substance use and develop a sense of cultural belonging among youth. They partnered with ADAI to develop a curriculum adapted from the traditional Canoe Journey, tailored specifically for their tribes, for youth to build healthy social and interpersonal skills and prevent the initiation of substance use (Donovan et al., 2015). See also Box 2-5 for details about Family Spirit, an EBP developed for Indigenous families to improve pregnancy and child development outcomes.

Approaches for Adults

Faith-Based and Community Settings

Faith-based settings, such as churches, mosques, synagogues, and other houses of worship, along with other community groups, are well positioned to provide universal preventive interventions and promote social norms that encourage help-seeking (HHS Partnership Center, 2023). Interventions can include support groups, SEL programs, and parenting courses. Leaders may serve as role models, changing social norms and reducing stigma around MEB disorders, by being open about MH or addiction issues, encouraging

BOX 2-4

Boys and Girls Clubs of Washington State Association’s Promising Out-of-School Program

Afterschool programs provide another setting for delivering prevention services to school-age children and adolescents. One example is the Boys & Girls Clubs of Washington State Association (BGCWA), which has developed and is implementing a 3-year pilot program in 14 of its club organizations to provide behavioral health staff support and trauma-informed training in partnership with the Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, Paxis Institute, and Norcliffe Foundation.

BGCWA deployed three implementation strategies. First, it hired 14 full-time behavioral support specialists, one for each of the 14 clubs (representing 169 different communities). They also led staff training, student socio-emotional learning programming, and family engagement. Second, guided by Paxis Institute, BGCWA trained 398 full-time staff and 674 part-time youth development professionals across Boys & Girls Clubs in the state in behavior management approaches that include trauma-informed care. As its third strategy, BGCWA implemented SEL programming using the SMART Moves Emotional Wellness program along with other efforts to provide environments responsive to a range of needs (i.e., “Quiet Corners and Sensory Tools”) and engage teens in small group sessions and build relationships with families and the community through its Family Nights (reprioritized after COVID-19 pandemic disruption).

The BGCWA initiative demonstrated that the workforce pipeline can be enhanced by community organizations participating in this work. The 14 clubs were asked to identify anyone on their staff who was on the continuum of psychology, counseling, or pursuing licensure or study, and if they were not licensed, the club arranged for supervision from a licensed professional in the community and paid for the supervisory contact. The program was viewed as a way to popularize the concepts related to MEB health, destigmatizing the topic, and normalizing the Boys & Girls Club as a place to go for help.

community members to seek help if they are struggling, and providing referrals to MH care providers. A variety of programs supporting protective factors and reducing risk or screening for risk have demonstrated effectiveness in exercise clubs and community spaces, such as libraries, parks, hair salons, and barber shops. Community-partnered depression screenings were

BOX 2-5

Evidence-Based Program: Family Spirit

Family Spirit is a home visiting program designed for Indigenous pregnant women and families. Family Spirit meets Department of Health and Human Services criteria for model effectiveness in tribal populations and can be used for non-Native populations with disparities in maternal and child behavioral health. Family Spirit sends paraprofessional home visitors to conduct visits starting during pregnancy and up until the child’s third birthday to deliver a curriculum that incorporates problem-solving skills and traditional tribal teachings. This curriculum involves 63 lessons that cover prenatal care, infant care, child development, toddler care, life skills and healthy living. The model was shown to be effective in improving child development and school readiness, maternal health, and positive parenting practices.

Family Spirit recommends that home visitors be members of the participating community and allows affiliates to make enhancements to meet needs at the local level. They also encourage paraprofessionals to have familiarity with local or tribal culture, traditions, and languages.

SOURCE: HomVEE, 2022.

demonstrated to be more effective than resources for individual programs improving MH-related quality of life, “physical activity, and homelessness risk factors, and shifted [use] away from hospitalizations and specialty medication visits toward primary care and other sectors, offering an expanded health-home model to address multiple disparities for depressed safety-net clients” (Wells et al., 2013, p.1268).

Approaches for Older Adults

Because the social and MEB needs of older adults are linked, strategies to improve MEB health will ideally be delivered along with health and social services to meet the MEB needs of low-income and homebound older adults (Forsman et al., 2011; Heisel, 2006). Strategies include supporting people by securing low-income senior housing and Section 8 housing vouchers, addressing social isolation and loneliness by providing opportunities for social engagement and volunteering, and facilitating access to improved access to MEB health services (see Box 2-6 for a promising program for older adults).

BOX 2-6

PEARLS: A Promising Preventive Intervention for Older Adults

PEARLS (Program to Encourage Active, Rewarding Lives) at University of Washington screens older adults for symptoms of depression and helps them build skills for more active and self-sufficient living. It is an evidence-based “program for all older adults, especially those who have limited access to depression care because of systemic racism, trauma, language barriers, low income, and/or where they live. This is because PEARLS was designed in collaboration with the organizations that deliver it, validated in partnership with the communities who use it, and adaptable to the people who need it” (UW, 2025).

It is delivered in the older adult’s home or “a community-based setting that is more accessible and comfortable for older adults who do not see other mental health programs as a good fit for them.” Staff at community-based organizations are trained to deliver the program. No counseling training or higher education is required.

SOURCE: Smith et al., 2023.

Workplace Settings

Workplaces can contribute to preventing MEB disorders and promote worker well-being through approaches that target the organization or target the individual worker. Individually targeted approaches are primarily employee assistance programs,1 which have been proliferating despite a lack of evidence of effectiveness (Fleming, 2024). At the organizational level, however, a psychosocial safety climate can play a role in worker well-being and requires organizational change strategies and work redesign (Bouzikos et al., 2022; Zadow et al., 2019). Organizational and group-level interventions also have a universal prevention focus—to support all workers by changing work conditions—addressing workplace stressors by strengthening protective factors (e.g., flexwork and self-scheduling) that benefit even those who do not pursue workplace resources for well-being (Fox, 2021). A systematic review by Fox and colleagues (2021) found that “[i]nterventions that most reliably improved well-being incorporated multiple facets of

___________________

1 EAPs are “voluntary, work-based program that offers free and confidential assessments, short-term counseling, referrals, and follow-up services to employees who have personal and/ or work-related problems.” See https://www.opm.gov/frequently-asked-questions/work-life-faq/employee-assistance-program-eap/what-is-an-employee-assistance-program-eap/ for more detail.

BOX 2-7

Promising Approach: Web-Based Apps

Kaiser Permanente, Veterans Health Administration (VHA), and other U.S. health care systems have launched digital ecosystems for MEB wellness (Wakefield et al., 2024). Many programs have been adapted for web- or app-based delivery, and others are being digitized to promote scale-up, with VHA programming being a great example. MEB health programs include varying types of professional support, from face-to-face interaction in a teleconference setting to entirely digital interactions through a web-based app. Digital apps have proliferated in recent years, intensified by pandemic-era needs for virtual delivery. Estimates indicate as many as 20,000 MEB health apps focused on a wide range of outcomes, from mindfulness and medication to symptoms of anxiety and depression. There is evidence of effectiveness for some telehealth interventions. For example, the Pathways for African American Success was tested in a randomized controlled trial comparing a telehealth to control and group arms and found to be effective (Murry et al., 2019).

change within their overall intervention and provided many opportunities for employee engagement” (p. 46).

Approaches for Veterans

One of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) many approaches to preventing suicide among veterans aims to increase safety planning and follow-up by caring contacts through emergency settings. When a veteran is “assessed as being at risk of suicide but still safe enough to be discharged home, VA deploys a suicide safety planning intervention, including lethal means safety counseling, while the person is still in the emergency department or urgent care center” (Carroll et al., 2020, p.3). This program was found to reduce “suicidal behaviors by almost half” (45 percent) “in the 6 months following emergency department visits” (Carroll et al., 2020, p.3). Box 2-7 discusses web-based apps.

IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE

Although dissemination and implementation (D&I) science is a relatively new field—with the first conference by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in

Health 17 years ago—like prevention science, it has been a part of scientific inquiry since at least the early 20th century (Dearing et al., 2023; Estabrooks et al., 2018). Implementation science is the “systematic, scientific approach to ask and answer questions about how we get ‘what works’ to people who need it, with greater speed, fidelity, efficiency, quality and relevant coverage” (UWDGH, 2024). The uptake of EBPs can take decades, and implementation science has emerged to reduce this gap, to speed the translation of discovery into real-world impact for all people. It can be drawn upon, with established frameworks, methods, outcomes, and strategies, when considering how to implement a national infrastructure to prevent MEB disorders. Implementation occurs at multiple levels, with each being related and optimally collaborative but having differing roles and responsibilities of the constituents. The overall meta-process of setting up a prevention infrastructure for MEB disorders speaks to policy makers, funders, and decision makers, while the hyperlocal community level that will be charged with frontline implementation activities and processes will include providers, faith leaders, educators, activists, and community partners. The interactions between and across these levels of constituents will happen within each community related to implementation of the infrastructure needed for the prevention effort, in a nuanced contextually appropriate way.

Implementation Strategies and Considerations

These implementation strategies encompass a variety of resources, organizations, individuals, and practical and conceptual tools to support the successful sustained implementation of an intervention or group of interventions. In addition to numerous frameworks, there are also blended implementation strategies, in which multiple strategies that address multiple levels or barriers to change are blended as one package (Powell et al., 2012). These include the Communities That Care framework (CTC), Promoting School-community-university Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) or Getting to Outcomes (GTO). CTC is a program that uses a “blended implementation strategy aimed at developing community-based prevention systems that take advantage of multiple evidence-based programs” (NASEM, 2019a, p. 225). This approach aims to foster comprehensive and coordinated community-led prevention that meets the needs of all young people in the community. Trained CTC coaches provide training and technical support to build capacity in community coalitions to use data to assess strengths, needs, and prevention gaps; develop prevention priorities and select and implement appropriate programs; and monitor results. PROSPER is a system that links university researchers with communities to support the delivery of programs related to promoting youth and family MEB well-being—the focus is on maximizing existing education infrastructure to build capacity and allow for sustained program

delivery in partnership with others who are attuned to local needs. The GTO toolkit offers support for community leaders to follow 10 steps: focus on problems; target goals, population, and outcomes; adopt programs; adapt programs; assess capacity and resources for implementation; plan to get started; monitor implementation; evaluate implementation; improve continuously; and sustain if successful. GTO is “intended to strengthen agencies’ and organizations’ use of prevention programs regardless of prior evidence of effectiveness”; it provides tools and supports to help communities identify the best EBP for their needs and context (see Fostering Healthy MEB Development in Youth [2019] for greater detail about blended implementation strategies) (NASEM, 2019a, p. 237). Federally funded implementation organizations include the Prevention Transfer Technology Centers and National Center for Mental Health: Dissemination, Implementation, and Sustainment.

Community Partnerships and Community-Led Work

A wealth of literature suggests that the most successful implementations are led by the community but supported by research and rigor to develop an infrastructure that can evaluate, realize, and sustain outcomes. Prevention requires a long-term lens, where outcomes might not be realized for years or until later in the life-span, and sustained implementation is critical.

Implementing preventive interventions must center the community, be led by it, and result in partnership between community members (see Box 2-8 for steps towards successful implementation of an intervention) (Gunn et al., 2022). Policy makers and funders must have relationships with the communities they represent to identify service gaps, new needs, and emerging prevention issues (NASEM, 2023). Researchers must have relationships with community partners to identify feasible methods and strategies to activate in real-world contexts and prioritize resources toward prevention that is meaningful to communities (NCDD, 2009). And community partners themselves must come together with a shared vision and motivation to enact change through adoption of EBP. While individual “go-it-alone” implementations help bring in innovation, community partnership is necessary to develop the infrastructure for sustained change.

Implementation research has identified that trust and respect are the most important facilitators of community partnerships, while time commitment is a potential barrier (Pellecchia et al., 2018). Implementation partnerships must consider the feasibility of time and resources necessary for success.

Funding Needs

Implementing evidence-based interventions requires adequate and sustained funding. There is some information about the costs of evidence-based

BOX 2-8

Eight Steps for Implementation of Preventive Interventions in Communities

As noted in Chapter 1, these steps are not necessarily sequential, and many can and should be concurrent.

- Identify the Need: To address a problem, communities will need to take steps to clearly identify it. This can be achieved through needs assessments, such as a community health assessment or improvement plan (CDC, 2024b).

- Select the Intervention: Choosing an intervention or package of interventions can be daunting. To support this process, communities can use implementation strategies, such as the GTO toolkit, partner with a university (i.e., PROSPER), or consult the University of Washington’s Center for Communities that Care. Communities can also independently refer to any number of clearinghouses, such as the ACF Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse (ACF, n.d.). Planning for sustainment should also be considered at this step, and tools such as A Designing for Dissemination & Sustainability Action Planner may be of use (D4DS, n.d.)

- Map the Constituents: Mapping the constituents allows communities to determine key players for implementation to ensure that those who are affected by the problem are part of the problem-solving process. Constituent mapping and collaboration also increase buy-in and ensure the implementation addresses the need. I-STEM is one tool that can offer key considerations and activities for conducting constituent engagement activities during implementation (Potthoff et al., 2023).

- Assess Barriers and Facilitators and Understand Context: Barriers and facilitators, or “determinants,” are categories of enablers

programs (e.g., from evidence clearinghouses, such as Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development2 and the National Center for Education Statistics). However, communities have different demographics, needs, and assets,

___________________

2 In July 2024, external funding concluded for Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. Blueprints’ leadership opted to “put Blueprints into dormancy until it is possible to secure a sustainable, high-impact path forward. The dormancy process entails updating information on the existing programs listed on our website and ensuring that Blueprints will remain freely available and searchable while in dormancy. This process will be completed by June 2025” (Buckley, 2024).

- or hindrances to intervention adoption, implementation, and sustainment and may include costs, workforce, and political or collective will in addressing the issue. Communities will need to be able to rapidly assess barriers and facilitators and develop strategies to address them. There are many tools to help support this assessment, such as a pragmatic context assessment tool (Robinson and Damschroder, 2023).

- Create a Logic Model: Once Steps 1–4 are completed, communities can create a road map for the implementation. There is no one correct way to do this, and the important part is that the approach is mapped out intentionally and prospectively and documents the identified need or problem, proposed intervention, required resources, target outcomes, and data and evaluation. The Implementation Research Logic Model may be a helpful starting point (Smith et al., 2020).

- Evaluate: As documented in the logic model, communities will need ongoing evaluation of the intervention to assess if it is effective or changes should be made.

- Adapt: A possible outcome of early evaluations may indicate to a community that an intervention is on the right track but needs to be adapted to suit the community’s needs. Adaptation is necessary to ensure maximum success and fit to context (Chambers, 2023) (Geng et al., 2023; Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2019).

- Sustain: Sustainment is a throughline for the entire process, as noted. In addition to tools such as D4DS, emerging evidence of types of sustainment strategies may be helpful information for communities (Wolfenden et al., 2024).

__________________

NOTE: ACF = Administration for Children and Families; CTC = Communities That Care; GTO = Getting to Outcomes; PROSPER = Promoting School-Community-University Partnerships to Enhance Resilience.

and each community will require a package of evidence-based interventions that is best suited to the local context. Very little published research is available on the cost of scaling prevention programs and associated components of the infrastructure, such as data and resources (see Fagan and colleagues [2019] for one review on increasing scale-up in U.S. public systems to prevent MEB disorders). The following examples are provided to (1) illustrate potential ways to estimate costs of programs, and (2) to help answer the question “what does an investment in prevention infrastructure buy a community?”

TABLE 2-1 Examples of General Cost Estimates for Selected Interventions

| Example of program | Cost |

|---|---|

| Delivering Parent Corps projected to cost $111,000 per school to each of more than 13,000 school districts in the nation (annually) | $1.45 billion |

| Delivering Nurse-Family Partnership (an evidence-based intervention) that costs $12,437 to each eligible family (465,000 eligible families in a year) | $5.78 billion |

| Delivering an evidence-based intervention (e.g., Good Behavior Game) to each elementary school student in birth cohort (approximately 3.6 million/year) at a per student cost of $160/individual | $576 million |

SOURCES: Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development, 2024a,c,d; Zaid et al., 2022.

One could assume an average of five evidence-based programs per county, with programs ranging in cost from an early childhood intervention, such as Nurse-Family Partnership, at $12,437 per family given the intense one-to-one nature of the intervention, to $10,000 to $12,000 per school for school-based interventions that involve training teachers and staff, and delivery to students and/or parents/guardians (Blueprints for Healthy Child Development, 2024b,c). Table 2-1 gives a general idea—for illustration purposes only—of the resources needed by states and localities to ensure that every community has the necessary support for MEB prevention programs.

Another way to think about program costs is to consider the full cost of planning and implementing an evidence-based program in a community (e.g., staffing, technology, office and space). A micro costing study estimated that first year cost of a community-based mental health prevention program in a population of 272,000 across 10 ZIP codes would cost $1,382,669 for the first year in 2022 dollars (Roy et al., 2024). Multiplying by 3,142 U.S. counties (acknowledging the vast range in population across counties), the cost of year 1 of a similar program being implemented in every county in the United States would be $4.3 billion. Note that counties vary widely in size, need, and local resources of all kinds, that the number of counties does not cover some tribal places and communities, and the 574 federally recognized tribal nations would need comparable levels of investment.

RESEARCH NEEDS TO IMPROVE THE EVIDENCE BASE ON INTERVENTIONS AND THEIR IMPLEMENTATION

Developing, testing, and establishing numerous evidence-based preventive interventions for MEB health is a notable achievement within the field of prevention science. However, there are evidence gaps and research needs

related to the existing body of knowledge and the D&I of the interventions. Although many interventions have been developed and demonstrated to show positive outcomes in rigorous trials, EBPs continue to be plagued with low rates of adoption in real-world community settings and even lower rates of sustainment (Wong et al., 2022).

Improving and Maintaining the Evidence Base on Existing Interventions

NIH and other research funders have invested significantly in rigorous research to establish dozens of demonstrated effective programs, policies, and practices that improve MEB outcomes (Murray et al., 2021). As noted, much of the evidence for prevention comes from studies of interventions targeting the early stages of life, among infants, children, adolescents, or their parents and caregivers. Other stages of life are less frequently represented, meaning the prevention and health promotion needs of middle-aged and older adults do not yet have the same volume of evidence-based strategies (Epstein et al., 2023).

Although the fields of prevention and implementation science have steadily increased their focus on developing interventions that reduce health disparities and can be used in any community and cultural context, the longest-established interventions in the evidence base to prevent MEBs predate this shift (Shelton and Brownson, 2023). There is a long history of research that does not include Black and Latino subpopulations, people with disabilities and LGBTQ people, and that was almost exclusively reliant on White male participants (NASEM, 2022; NIMHD, 2024). As such, some interventions with the longest history of RCTs or other research may not be applicable in diverse communities for a number of reasons. Therefore:

- Well-tested interventions may still not apply to groups that were excluded from any of the original studies.

- The interventions may not be well received or applicable in all communities (NIHB, 2009).

- The interventions were not developed to and are not equipped to reduce MEB health disparities (Sanchez et al., 2023).

The first and third points above do not mean that existing EBPs cannot be useful in populations in which they were not included when programs were tested but careful attention must be given to needs and cultural contexts of every community where an EBP is being implemented (Sanchez et al., 2023). These considerations can be developed by focusing on research that assesses generalizability of interventions not only to different groups of people but across different real-life settings.

RECOMMENDATION 2-1: The National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and philanthropic organizations should fund more research on the prevention of mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) disorders that addresses research gaps related to intervention development (to identify what works and the certainty and magnitude of outcomes) and implementation (to identify how to deliver and sustain interventions with fidelity). This research should prioritize interventions that target MEB health inequities, are needed for different age groups, and are co-created with the populations they are intended to serve.

A few process options may be helpful for funders to practically identify research needs, further health equity, and focus on community cocreation in research going forward. Funders can use existing taxonomies,3 develop new ones, or a combination thereof to systematically and consistently identify further evidence gaps and research needs and set priorities so appropriate proposals are funded and the research needs are addressed. Additionally, funders could request that study sections, scientific review officers, and others in similar roles familiarize themselves with theoretical frameworks for expanding fair opportunities for all people to attain their full health potential to be used during the proposal review process. Funders also can set aside sufficient resources for community–academic partnerships specifically for evaluation to support communities that have or are developing practice-based evidence to partner with scientists.

When developing requests for proposals, funders can emphasize the need for

- Interventions that can be tailored for different contexts, settings, and age ranges, using data that has been disaggregated by race and ethnicity, and for an array of participants, from those who are easily engaged to those who have been historically excluded or underrepresented or who experience language access barriers;

- Co-design, co-production, or co-creation of intervention and implementation approaches between investigators, community members, and/or future participants in research proposals and projects; and

- Implementation plans for interventions that prove successful including adequate attention to pre-implementation timelines and resource allocation, understanding that pre-implementation requires different timelines under different community contexts.

___________________

3 See, for example, the clinical prevention foundational issues, analytic framework, and dissemination and implementation taxonomies for identifying research gaps at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/26351/ or the Reconnecting Youth Evidence Gap Map at https://youth.gov/youth-topics/opportunity-youth/reconnecting-youth?q=egm.

Improving Knowledge Dissemination

I get bombarded, as a school district director, from calls all over the

country trying to sell me programs as evidence-based practices,

and you look at the effect sizes, if they have any, and they’re only

observable in laboratory settings. Our school leadership doesn’t

know how to discern that.

—Joe Neigel, Monroe School District Director of Prevention Services,

Washington

NIH and other research funders have invested significantly in rigorous research to establish dozens of demonstrated effective programs, policies, and practices that improve MEB health outcomes (Murray et al., 2021). Two major ways new research is disseminated and eventually implemented are public health campaigns and evidence-based clearinghouses. The former tend to focus more on shifting social norms and behaviors toward promoting health and well-being and reducing disease (ODP, 2023) but can include concrete tips and strategies for communities or leaders to adopt. For example, CollegeAIM is an implementation guide that can be found on NIH’s Office of Disease Prevention’s public health campaigns webpage; it not only evaluates 60 different interventions designed to prevent harmful drinking among college students but provides detailed preimplementation considerations (how administrators can evaluate needs, assess which blend of strategies to use, and assess cost and other resources needed) (NIAAA, 2019b). Evidence-based clearinghouses4 are web-based collections of programs and practices often centered around a particular topic or age group (Lee et al., 2022). Their landscape is dotted with multiple sets of standards, multiple sources, and a range of proprietary or trademarked interventions (see Appendix B for a sample of some of the evidence-based clearinghouses available that share information about preventive interventions for MEB disorders, although most of them do not exclusively cover these).

Barriers to adopting interventions include implementers not being aware of existing interventions or knowing which are applicable to their population or setting needs. Implementers may not be aware of evidence clearinghouses that list and, in some cases, evaluate and rate interventions. In addition, implementers may not understand these rating systems. Many of these issues are compounded by a related challenge: at least three dozen prevention-related evidence clearinghouses exist (Burkhardt et al., 2015; Lee-Easton and Magura, 2023; Lee et al., 2022). The evidence base of interventions is not disseminated or implemented well across communities for a variety of reasons, and developing interventions with validity for

___________________

4 Also called “registries,” although this report uses “clearinghouses” whenever possible.

diverse groups of people and settings is needed, as is continued research and development for existing interventions.

Some clearinghouses only include interventions for child and adolescent populations, and some are broad, spanning prevention and treatment interventions to support physical and MEB health. Clearinghouses can collate and rank prevention programs to support decision makers considering which interventions to implement to promote MEB health. However, the landscape is not able to support these decision makers, because clearinghouses are created, overhauled, and closed without harmonized goals and standards. Reinforcing the overlapping and sometimes confusing aspect of this is a kind of cross-referencing by clearinghouses. For example, Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development included “Endorsements” where applicable in each intervention it reviews, noting which other clearinghouses also recommend the program, presumably to strengthen its credibility. Another example is Youth.gov, which has a webpage titled “The Federal Understanding of the Evidence Base,” linking to clearinghouses managed by AmeriCorps (two), U.S. Agency for International Development (one), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA, one); Department of Defense and USDA-collaboration (one), Department of Education (two); Department of Health and Human Services (HHS, 16); Department of Justice (three); and Department of Labor (one) (Youth.gov, n.d.). These clearinghouses cover topics mostly related to youth but have vast range among what part of the prevention-treatment continuum they address, settings, types of programs, and intended outcomes (some are focused on risk and protective factors, while others focus on reducing specific discrete outcomes, such as teen pregnancy).

The proprietary nature of programs poses barriers as well. These include challenges to transparency and collaboration, and potential conflicts of interest or biases in how those interventions are evaluated (Supplee et al., 2022). Clearinghouses typically include limited information about implementation factors that affect whether impacts from efficacy trials are achieved in real-world delivery. The patchwork nature of the landscape is exacerbated by inconsistent evaluation of programs: many clearinghouses lack transparency about inclusion criteria, and those that offer grades (e.g., “highly recommended” or “strong evidence for. . .”) do not use standardized evaluation measures (Lee-Easton and Magura, 2023). Between the standard for which evidence is assessed and the potentially differing criteria (e.g., one clearinghouse highly prioritizes a criterion, such as health equity, while another does not explicitly consider it at all), high grades may mean vastly different things. One study by Zheng, Wadhwa, and Cook (2022) reviewed 13 clearinghouses and found that 82 percent of 2,525 programs were rated by a single clearinghouse, and of those rated by more than one, agreement of effectiveness was reached about half the time. Similarly, a 2024 study

reviewed 1,359 programs over 10 clearinghouses and found “83% of them were assessed by a single clearinghouse and, of those rated by more than one, similar ratings were achieved for only about 30% of the programs” (Wadhwa et al., 2024). This analysis reveals that the majority of programs are only included in one clearinghouse, limiting replication opportunities for evaluation, and when they are evaluated by multiple clearinghouses, they receive dissimilar ratings more often than not. This inconsistency in inclusion and grading renders clearinghouses less useful to communities trying to determine which programs would be most effective. As an example, one of the programs identified in this report was not endorsed and another was considered “promising” by one clearinghouse. In both cases, another clearinghouse had fully endorsed both programs. For example, Familias Unidas (see Box 3-3) is rated as a Promising Program on Blueprints for Healthy Child Development but given the highest endorsement for the strength of evidence by the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (Pantin et al., 2009). Again, reference in this report to a specific program should not be considered an endorsement by this committee, but illustrative of the needs of the prevention infrastructure.

Perhaps the most well-known clearinghouse of preventive interventions for MEB disorders was the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Registry of Effective Prevention Programs (NREPP), which was launched in 1997. SAMHSA renamed this the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices and added treatment interventions. In late 2017, NREPP was suspended, and in early 2018 funding for the work of evaluating and rating the evidence for programs listed was terminated (Dodge Foundation, 2018). An effort to standardize and preserve the data in the original evidence clearinghouse was undertaken by the Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative, which archived 80 percent of the NREPP links (Bryant-Comstock, 2019). In 2018, SAMHSA launched the Evidence-Based Practices Resource Center (EBPRC) which is extant and is simply a collection of resources that are not rated or evaluated. This has left the field of MEB disorder prevention with incomplete, outdated, and discordant resources to navigate the evidence base.

Despite these challenges, evidence-based clearinghouses have significant potential to improve MEB outcomes for all communities, particularly those that are disproportionately affected, by supporting the dissemination of interventions that promote MEB health and being transparent about the process used to evaluate the intervention (Hirsch et al., 2023). The committee learned from a Federal Register notice and SAMHSA outreach to the field that the agency has been seeking input on the importance and organization of a potentially relaunched centralized clearinghouse of evidence-based prevention programs. The Federal Register notice stated that the EBPRC does not meet the 21st Century Cures Act vision to “make

the metrics used to evaluate applications . . . and any resulting ratings of such applications, publicly available,”5 emphasizing a transparent rating and review system for EBPs (Mayo-Wilson et al., 2022). SAMHSA’s actions are good steps forward. To support SAMHSA’s work, the committee underscores key components of an evaluation system that are necessary to fill the gap of a “decision support tool,” as NREPP was designed to be:

- A set of criteria for both including and evaluating programs that considers both EBP and PBE, implementation, dissemination, fit to population, and generalizability.

- A clear focus on including programs that are diverse and already are/can be tailored to meet the needs of underserved and excluded subpopulations, which should include groups across the life course and settings outside of school.

- A system that can clearly sort programs between levels of prevention and, in particular, includes community-level universal primary/primordial interventions.

- A system that accounts for the proprietary nature of many programs, protects against bias in the evidence submitted and review process, and does not include programs that have not been evaluated. For example, in 2017, one review of 112 programs newly added to NREPP found that 78 percent had some conflict of interest. In the majority of those cases, the point of contact for the program also authored at least one document reviewed as evidence for inclusion (Gorman, 2017); and

- Clear cost/funding information for each program, which should include up-front and reoccurring costs to run programs once they have been implemented in a community and the potential cost of hiring workforce as applicable.

Many clearinghouses have no dedicated and sustained funding source, making it hard to maintain quality or respond dynamically as the evidence base changes. Sustained, non-grant-dependent resourcing is needed. Ideally, support for select clearinghouses would be built into SAMHSA’s budget as a permanent component. In addition to procedures for regularly updating and maintaining the clearinghouse, a feedback loop is needed to outline data collection needs as a program is implemented, so that evaluation can take place during implementation and adjustments made—and learnings (such as tailoring of an intervention for a specific cultural or language contexts) integrated in the clearinghouse.

___________________

5 21st Century Cures Act, Public Law 114-255, §7002, 114th Cong., 1st sess. (December 13, 2016).

Prevention leaders, such as coordinators and directors, in partnership with implementers, are making decisions with significant resource constraints. Opacity and fragmentation of the evidence of effective MEB disorder prevention programs for their communities should not be one of them. With the resources they are able to dedicate to prevention, the committee believes these prevention leaders should be able to explore existing programs that may work for them and use that information to consider which innovative new programs would be promising for the community if there is a gap. A centralized decision support tool is needed to navigate the evidence base, and the committee believes that SAMHSA’s efforts on this point are laudable and important to continue and ultimately lead to the re-establishment of NREPP or something like it.

An evidence base exists of tested and effective MEB disorder preventive and health promotive interventions particularly targeted for children, youth, and families, which address a variety of BH outcomes, and many are cost effective. The evidence base for other stages of the life course is not as robust. Also, the reach and impact of these interventions is limited for several reasons:

- Barriers to successful adoption (knowledge of interventions at all, or difficulty accessing them because of clearinghouse lack of usefulness or cost barriers);

- Other barriers to implementation: lack of tools/knowledge to implement them successfully (no preimplementation plan for sustainability), necessary funding levels not met in the real world and inadequate funding mechanisms, failure to consider implementation factors that moderate impact; and

- Generalizability and external validity: limitations include narrow age range and study demographics and lack of ecological validity (e.g., inadequate research with underrepresented racial, ethnic, and tribal populations, lack of cultural or language appropriateness, or lack of consideration for cultural or other ecological contexts that shape effectiveness of interventions).

CONCLUSION 2-1: Existing prevention strategies and evidence clearinghouses—as critical aspects of the prevention and health promotion infrastructure—are necessary but not sufficient for meeting population mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) health needs and reducing disparities in MEB outcomes that originate during preconception and early life and can increase along the life course.

RECOMMENDATION 2-2: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) should manage and maintain a

centralized and dynamic evidence clearinghouse for mental, emotional, and behavioral health that promotes standardization of criteria for inclusion and evaluation. The clearinghouse should include information about intervention effectiveness, guidance for implementation, and a focus on prevention strategies that address the needs of diverse communities.

To support uptake of effective interventions and integrate practice-based evidence, SAMHSA should also

- Develop clearinghouse navigation tools to help implementers find relevant strategies, ensure implementation quality, and increase the likelihood of impact; and

- Work with state and other grantees to develop a mechanism to integrate evaluation of implementation, new knowledge, and community experience.

Possible criteria for inclusion within this centralized and dynamic clearinghouse could include:

- Quality of the evidence: reliability and internal validity;

- Generalizability of results to specific and new subpopulations, settings, and geographic locations (external validity); and

- Preimplementation, implementation, and cost considerations.

Clearinghouse usability considerations include having straightforward search functions and being tailorable for different needs, concise, and jargon free. To operationalize a focus on health equity, SAMHSA could include a transparent and consistent section on health equity considerations, e.g., whether there are differential impacts across populations and if an intervention worsens, sustains, or reduces MEB health disparities (Hirsch et al., 2023). Managing this resource may fall under the role of the Evidence-Based Practices Innovation and Dissemination Team under SAMHSA’s National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory, as they currently disseminate information about programs through SAMHSA’s EBPRC, along with training and technical assistance providers, listservs, and social media (GAO, 2024). SAMHSA could also provide technical assistance to communities to select appropriate, contextually relevant, and culturally responsive EBPs to meet their needs and active implementation support to ensure success. It could be a function of the HHS Behavioral Health Coordinating Council (or similar cross-departmental structure) to work with SAMHSA in accomplishing working with state grantees to develop a mechanism to further integrate evaluation along with dissemination of new research.

REFERENCES

Abraham, E., C. Blanco, C. Castillo Lee, J. B. Christian, N. Kass, E. B. Larson, M. Mazumdar, S. Morain, K. M. Newton, A. Ommaya, B. Patrick-Lake, R. Platt, J. Steiner, M. Zirkle, and M. Hamilton Lopez. 2016. Generating knowledge from best care: Advancing the continuously learning health system. NAM Perspectives. Discussion paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201609b.

ACF (Administration for Children and Families). n.d. Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse. https://preventionservices.acf.hhs.gov/ (accessed December 16, 2024).

APA (American Psychological Association). 2005. Policy Statement on Evidence-Based-Practice in Psychology. http://www2.apa.org/practice/ebpstatement.pdf. (accessed January 7, 2025).

Barlow, J., E. Coren, and S. Stewart-Brown. 2002. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of parenting programmes in improving maternal psychosocial health. British Journal of General Practice 52(476):223–233. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12030667 (accessed December 31, 2024).

Bartgis, D., and D. Bigfoot. n.d. Evidence-based practices and practice-based evidence. https://ncuih.org/ebp-pbe/ (accessed October 26, 2024).

Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. 2024a. Good behavior game. https://www.blueprintsprograms.org/programs/20999999/good-behavior-game/ (accessed September 9, 2024).

Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. 2024b. Lifeskills training. https://www.blueprintsprograms.org/programs/5999999/lifeskills-training-lst/ (accessed October 9, 2024).

Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. 2024c. Nurse-family partnership. https://www.blueprintsprograms.org/programs/35999999/nurse-family-partnership/ (accessed December 11, 2024).

Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. 2024d. Parentcorps. https://www.blueprintsprograms.org/programs/1291999999/parentcorps/ (accessed December 11, 2024).

Bouzikos, S., A. Afsharian, M. Dollard, and O. Brecht. 2022. Contextualising the effectiveness of an employee assistance program intervention on psychological health: The role of corporate climate. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095067.

Brown, C. H., G. Curran, L. A. Palinkas, G. A. Aarons, K. B. Wells, L. Jones, L. M. Collins, N. Duan, B. S. Mittman, A. Wallace, R. G. Tabak, L. Ducharme, D. A. Chambers, C. Neta, T. Wiley, J. Landsverk, K. Cheung, and G. Cruden. 2017. An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annual Review of Public Health 20(38):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044215.

Bryant-Comstock, S. 2019. Results first initiative saves NREPP from obscurity. https://www.cmhnetwork.org/news/results-first-initiative-saves-nrepp-from-obscurity/ (accessed December 31, 2024).

Buckley, P. 2024. The blueprints bulletin. Issue 29, October 2024. https://www.blueprintsprograms.org/issue-no-29/ (accessed December 16, 2024).

Burkhardt, J. T., D. C. Schröter, S. Magura, S. N. Means, and C. L. Coryn. 2015. An overview of evidence-based program registers (EBPRS) for behavioral health. Evaluation and Program Planning 48:92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.09.006.

Carroll, D., L. K. Kearney, and M. A. Miller. 2020. Addressing suicide in the veteran population: Engaging a public health approach. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11:569069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569069.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2023. Out-of-school time. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/ost.htm (accessed September 11, 2024).

CDC. 2024a. About adverse childhood experiences. https://www.cdc.gov/aces/about/index.html (accessed November 11, 2024).

CDC. 2024b. Community planning for health assessment: CHA & CHIP. https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/public-health-strategy/public-health-strategies-for-community-health-assessment-health-improvement-planning.html (accessed November 11, 2024).

CEBC (The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare). 2024. Nurse-family partnership. https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/nurse-family-partnership/detailed (accessed December 16, 2024).

Chambers, D. A. 2023. Advancing adaptation of evidence-based interventions through implementation science: Progress and opportunities. Frontiers in Health Services 3:1204138. https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2023.1204138.

Cioffi, C. C., D. S. DeGarmo, and J. A. Jones. 2021. Participation in the fathering through change intervention reduces substance use among divorced and separated fathers. Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment 120:108142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108142.

Day, L. 2023. Mental health promotion pilot: Year 1 report. http://www.washingtonclubs.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/BGCWA_Mental-Health-Promotion-Pilot_Year-1-report.pdf (accessed January 10, 2025).

Day, L. 2024. Mental health promotion pilot: Year 2 report. http://www.washingtonclubs.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/BGCWA_Mental-Health-Pilot-Report_Year-2.pdf (accessed January 10, 2025).

Dodge Foundation. 2018. SAMHSA’s Registry of Evidence-Based Programs (NREPP) Suspended. News Release. https://pgdf.org/samhsas-registry-of-evidence-based-programs-nrepp-suspended/ (accessed January 2, 2025).

D4DS. n.d. D4DS planner. https://d4dsplanner.com/ (accessed October 25, 2024).

Dearing, W. J., F. K. Kee, and T.-Q. Peng. 2023. Historical roots of dissemination and implementation science. In Dissemination and implementation research in health, edited by D. Chambers: Oxford University Press. Pp. 69–85.

Donovan, D. M., L. R. Thomas, R. L. Sigo, L. Price, H. Lonczak, N. Lawrence, K. Ahvakana, L. Austin, A. Lawrence, J. Price, A. Purser, and L. Bagley. 2015. Healing of the canoe: Preliminary results of a culturally tailored intervention to prevent substance abuse and promote tribal identity for Native youth in two Pacific Northwest tribes. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research Journal 22(1):42–76. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.2201.2015.42.

Epstein, M., R. Kosterman, and R. F. Catalano. 2023. The potential for prevention science in middle and late adulthood: A commentary on the special issue of prevention science. Prevention Science 24(5):808–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01544-y.

Estabrooks, P. A., R. C. Brownson, and N. P. Pronk. 2018. Dissemination and implementation science for public health professionals: An overview and call to action. Preventing Chronic Disease 15:E162. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180525.

Fagan, A. A., B. K. Bumbarger, R. P. Barth, C. P. Bradshaw, B. Rhoades Cooper, L. H. Supplee, and D. K. Walker. 2019. Scaling up evidence-based interventions in US public systems to prevent behavioral health problems: Challenges and opportunities. Prevention Science 20:1147–1168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-01048-8.

Felitti, V. J., R. F. Anda, D. Nordenberg, D. F. Williamson, A. M. Spitz, V. Edwards, and J. S. Marks. 1998. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14(4):245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8.

Fleming, W. J. 2024. Employee well-being outcomes from individual-level mental health interventions: Cross-sectional evidence from the United Kingdom. Industrial Relations Journal 55(2):162–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/irj.12418.

Forgatch, M. S., G. R. Patterson, D. S. Degarmo, and Z. G. Beldavs. 2009. Testing the Oregon delinquency model with 9-year follow-up of the Oregon divorce study. Development and Psychopathology 21(2):637–660. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409000340.

Forsman, A. K., J. Nordmyr, and K. Wahlbeck. 2011. Psychosocial interventions for the promotion of mental health and the prevention of depression among older adults. Health Promotion International 26(suppl_1):i85–i107. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dar074.

Fox, K. E., S. T. Johnson, L. F. Berkman, M. Sianoja, Y. Soh, L. D. Kubzansky, and E. L. Kelly. 2021. Organisational- and group-level workplace interventions and their effect on multiple domains of worker well-being: A systematic review. Work & Stress 36 (1):30–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2021.1969476.

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2024. Behavioral health: Activities of the National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. GAO-24-106760. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-24-106760.pdf (accessed December 31, 2024).

Geng, E. H., A. Mody, and B. J. Powell. 2023. On-the-go adaptation of implementation approaches and strategies in health: Emerging perspectives and research opportunities. Annual Review of Public Health 44(1):21–36. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurevpublhealth051920-124515.

Gorman, D. M. 2017. Has the national registry of evidence-based programs and practices (NREPP) lost its way? International Journal of Drug Policy 45:40–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.010.

Green, L. W., and J. P. Allegrante. 2020. Practice-based evidence and the need for more diverse methods and sources in epidemiology, public health and health promotion. SAGE Publications.

Gunn C. M., L. S. Sprague Martinez, T. A. Battaglia, R. Lobb, D. Chassler, D. Hakim, M. L. Drainoni. 2022. Integrating community engagement with implementation science to advance the measurement of translational science. J Clin Transl Sci 1;6(1):e107. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2022.433.

Healing of the Canoe. 2024. About us. https://healingofthecanoe.org/about/ (accessed September 11, 2024).

Heisel, M. J. 2006. Suicide and its prevention among older adults. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 51(3):143–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370605100304.

HHS Partnership Center. 2023. Youth mental health and well-being in faith and community settings: Practicing connectedness a toolkit of the HHS partnership center. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/youth-mental-health-and-well-being-in-faith-and-community-settings.pdf (accessed September 11, 2024).

Hirsch, B. K., M. C. Stevenson, and M. L. Givens. Evidence clearinghouses as tools to advance health equity: What we know from a systematic scan. Prevention Science 24:613–624 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01511-7.

HomVEE (Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness). 2022. Family spirit. https://homvee.acf.hhs.gov/models/family-spiritr (accessed December 11, 2024).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2013. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13444.

Latimore, A. D., E. Salisbury-Afshar, N. Duff, E. Freiling, B. Kellett, R. D. Sullenger, and A. Salman. 2023. Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of substance use disorders through socioecological strategies. NAM Perspectives 9(6). https://doi.org/10.31478/202309b.

Lee, M. J., M. J. Maranda, S. Magura, and G. Greenman. 2022. References to evidence-based program registry (EBPR) websites for behavioral health in U.S. state government statutes and regulations. Journal of Applied Social Science 16(2):442–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/19367244221078278.

Lee-Easton, M. J., and S. Magura. 2023. Discrepancies in ratings of behavioral healthcare interventions among evidence-based program resources websites. Inquiry 60:469580231186836. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580231186836.

Mayo-Wilson E., S. Grant, and L. H. Supplee. July 2022. Clearinghouse standards of evidence on the transparency, openness, and reproducibility of intervention evaluations. Prevention Science 23(5):774–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01284-x.

Murray, D. M., L. F. Ganoza, A. J. Vargas, E. M. Ellis, N. K. Oyedele, S. D. Schully, and C. A. Liggins. 2021. New NIH primary and secondary prevention research during 2012–2019. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 60(6):e261–e268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.006.

Murry, V. M., C. Berkel, M. N. Inniss-Thompson, and M. L. Debreaux. 2019. Pathways for African American success: Results of three-arm randomized trial to test the effects of technology-based delivery for rural African American families. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 44(3):375–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsz001.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019a. Fostering healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral development in children and youth: A national agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25201.

NASEM. 2019b. Vibrant and healthy kids: Aligning science, practice, and policy to advance health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25466.

NASEM. 2019c. The promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25388.

NASEM. 2020. Promoting positive adolescent health behaviors and outcomes: Thriving in the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25552.

NASEM. 2022. Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26479.

NASEM. 2023. Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26834.

NCDD (National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation), International Association for Public Participation, and the Co-Intelligence Institute. 2009. Core Principles for Public Engagement. https://www.ncdd.org/uploads/1/3/5/5/135559674/pepfinal-expanded.pdf (accessed February 25, 2025).

NIAAA (National Institute on Alcohal Abuse and Alcoholism). 2019a. Individual-level strategies. https://www.collegedrinkingprevention.gov/collegeaim/individual-strategies (accessed October 13, 2024).

NIAAA. 2019b. Planning alcohol interventions using NIAAA’s collegeaim alcohol intervention matirx. https://www.collegedrinkingprevention.gov/sites/cdp/files/documents/NIAAA_College_Matrix_Booklet.pdf (accessed December 31, 2024).

NIHB (National Indian Health Board). 2009. Healthy Indian country initiative promising prevention practices resource guide: Promoting innovative tribal prevention programs. https://www.nihb.org/docs/04072010/2398_NIHB%20HICI%20Book_web.pdf (accessed September 9, 2024).

NIMHD (National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities). 2024. Diversity and inclusion in clinical trials. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/understanding-health-disparities/diversity-and-inclusion-in-clinical-trials.html (accessed September 11, 2024).