Rethinking Race and Ethnicity in Biomedical Research (2025)

Chapter: Summary

Summary1

The concepts of race and ethnicity have been used in a variety of contexts throughout history, and their use has evolved over time. Often connected to observable traits such as skin color, “race” developed from a belief in innate differences between socially created groups of people and has been used to justify unequal treatment. The use of race can be traced to the origins of the United States and hundreds of years into history.2 Ethnicity, sometimes used as a synonym for race, can be defined as a more recent socially and politically constructed term used to describe people from a similar national or regional background who share common cultural, historical, and social experiences. As sociopolitical constructs, race and ethnicity have been used in society to determine citizenship, rights, status, and in other discriminatory ways.

The everyday use of race and ethnicity is so engrained in U.S. society that these constructs are commonly used as demographic identifiers in many settings—on a loan application or at the doctor’s office. Race and ethnicity are widely used in medicine, including in cardiology, nephrology, obstetrics, urology, and pulmonology. A recent systematic review found that 30 percent of 414 pediatric clinical practice guidelines incorporated race or ethnicity phrases, often in harmful ways. Yet race and ethnicity are an important part of how people describe themselves and experience the world.

With the ubiquitous use of race and ethnicity, it is unsurprising to find the terms used in biomedical research, which spans research on human health and disease from preclinical methods to population health. Federal biomedical research grants require the use of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) minimum set of racial and ethnic categories for tracking enrollment of study participants. The OMB directive states, “the race and ethnicity categories set forth are sociopolitical constructs and are not an

___________________

1 References are not included in this report summary. Citations appear in subsequent report chapters.

2 See Chapter 2 for discussion of the meaning and history of race and ethnicity.

attempt to define race and ethnicity biologically or genetically.” However, using these categories for the purpose of inclusion has been conflated with other uses, such as scientific analyses.

These categories are not useful proxies for biology because there is no genetic, or biological, basis for race. The Human Genome Project found in 2003 that humans were 99.9 percent identical to each other at the DNA level. Moreover, genetic variation overlaps across racial and ethnic groups instead of creating distinct clusters. A single racial category used in social and political contexts encompasses people with diverse genetic features. Combining these individuals into one group for scientific analyses can lead to oversimplification, misinterpretation, and inaccurate science. Moreover, the use of race and ethnicity in this scientific context can distract from deeper investigations into the true drivers of disease (e.g., genetics, environmental exposures).

It is well established that race and ethnicity are not valid biological markers, but there is a lack of consensus as to whether and how they should be used in research studies or in medical decision making. For example, race and ethnicity categories have been useful in identifying and tracking health disparities such as the profound disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Conversely, practices of race correction or race adjustment—that is, developing clinical calculators or guidelines that modify their output based on the patient’s race or ethnicity—have faced criticism in recent years for contributing to health disparities and reinforcing the misconception that there are innate biological differences between racial and ethnic groups. However, removing race and ethnicity from clinical tools, algorithms, and guidelines is complicated and requires comprehensive evaluation to assess potential tradeoffs that can vary across populations and depend on the health outcome of interest.

Given the complexity of these considerations, researchers need guidance for deciding if, when, and how to use race and ethnicity, so that when they choose to do so, their approach is rigorous and valid. This report provides resources to guide decision making about the use of race and ethnicity in biomedical research, including consideration of when other measures could better address scientific aims. The committee engaged in this work with the goal that the biomedical research community will move beyond harmful uses of race and ethnicity that create or perpetuate health inequities to a future where race and ethnicity are used thoughtfully in research and its clinical applications.

THE COMMITTEE’S TASK AND APPROACH

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) assembled an ad hoc committee, composed of biomedical scientists, physician and nurse scientists, epidemiologists, social scientists, and experts in law, anthropology, ethics, and clinical informatics, to assess the current use of racial and ethnic categories in biomedical research, review existing guidance, and provide recommendations to guide the future use of race and ethnicity. The Doris Duke Foundation and Burroughs Wellcome Fund asked the committee to provide guidance to the research community on whether, when, and how to use race and ethnicity in biomedical studies.

In developing its approach, the committee defined biomedical research as scientific research across biological, social, and behavioral disciplines that pertains to human health.3 This report focuses on biomedical research beyond preclinical models on the translational spectrum because race and ethnicity become increasingly relevant in research with groups of people.

The committee assessed current practices related to race and ethnicity across a range of research contexts including race correction, medical devices, secondary data analysis, and clinical decision-making tools, including the expanding use of artificial intelligence (AI)4 in clinical algorithms. The committee also examined existing guidance for the use of race and ethnicity in related sectors such as publishing guidelines and clinical guidelines development. Based on this analysis, the committee developed recommendations for biomedical scientists, journal publishers and editors, professional societies, and funders of biomedical research. The committee created resources, which can be found throughout the report, to help researchers implement its high-level recommendations.

COMPLEXITY AND NUANCE IN DEFINING AND UNDERSTANDING RACE AND ETHNICITY

Using race and ethnicity in biomedical research is challenging because there are multiple truths and realities that coexist in tension with one another. For instance, describing race and ethnicity as social constructs gives rise to an intrinsic tension—race and ethnicity affect people’s experiences and social realities, yet these concepts are not themselves suitable proxies for biological mechanisms. In addition, the concepts of race and ethnicity are defined, understood, and used differently across various domains of research and medicine, which has exacerbated confusion and misunderstanding. Sociology, for example, has long described race and ethnicity as socially constructed, but other disciplines and public perception have been slower to adopt this understanding. This section will unpack why race and ethnicity are not suitable proxies for biology, discuss why it is inappropriate to ignore race and ethnicity altogether, and address apparent contradictions in certain use cases.

The pervasive use of race and ethnicity in society has driven a persistent misconception that humans can be divided into biologically separate groups with distinct characteristics. This idea, known as “race science,” has been disproven by decades of research. Research has made clear that race has no genetic basis—that is, race does not explain human genetic variation and vice versa. Human genetic variation is continuous and overlapping, thus refuting the notion of discrete human races. Some genetic variants can be geographically clustered, reflecting long periods of geographic isolation of human populations, which is why some genetic diseases appear

___________________

3 The committee did not focus specifically on genetics and genomics research, because these fields were addressed by a 2023 National Academies report, Using Population Descriptors in Genetics and Genomics Research.

4 See Chapters 3, 4, and 6 for more information on AI.

more prevalent in some racial and ethnic groups than in others. For example, sickle cell disease has been stereotyped as a “Black” disease in the United States, but the geographic distribution of sickle cell trait is explained by the global distribution of malaria, not race. An evolutionary adaptation that protects against malaria, sickle cell trait occurs in many countries, in people who may identify with various racial and ethnic categories.

Perhaps seeming at odds with these findings, differences in individual characteristics such as eye, skin, and hair color are partially explained through genetic inheritance, but the idea that race has a biological basis is erroneous. Skin color is often viewed as synonymous with race but is a complex trait with contributions from multiple genes and the environment. Skin color does not follow a clear distribution based on racial and ethnic categories, and it is not a substitute for measuring underlying biological mechanisms. In other words, visible differences in traits like eye color do not mean that cells in the eye function differently, nor is eye color a proxy for eye function. The purported connection between race and biology falls apart completely when examining other complex traits and genetic variation.

Conclusion 5-5:5 Genetic differences among groups of people are not racial differences. Genetic differences may have meaning in biology and a role in medicine and research. Race, though, is not a substitute for unseen or unmeasured biological predictors of interest.

Though not biological, race and ethnicity shape social realities and lived experiences. Identity is highly personal, and race and ethnicity are important elements of how people see themselves, relate to others, and experience the world. An added complexity is that the terms individuals use to identify themselves have changed across generations as has the extent and form of racism they have experienced. Referring to race and ethnicity as social constructs may be useful among scientists to reinforce that these concepts are not rooted in biology, but this phrase can appear dismissive, labeling the social reality and impacts of race and ethnicity as imagined or unimportant.

Health disparities are one manifestation of the social realities of race and ethnicity. While research may uncover differences in the prevalence or severity of disease across groups of people, evidence indicates that race and ethnicity do not themselves cause health differences. Rather, because they are socially constructed, race and ethnicity can be correlated with factors such as social determinants of health (e.g., socioeconomic status, discrimination), which influence biological systems and health. Differences in disease prevalence and contributing social and environmental factors do not indicate that underlying biological mechanisms differ across racial and ethnic groups. For example, rates of cardiovascular disease may vary across populations, but the cellular mechanisms and biological pathways are generally the same despite some genetic variation among individuals. In fact, many molecular and cellular

___________________

5 The conclusions in this summary are numbered according to the chapter of the main text in which they appear.

mechanisms are so fundamental that they often do not differ across species, much less racial or ethnic groups.

In clinical settings race and ethnicity are commonly described as risk factors and used to assess patients’ disease risk. This can sometimes be misconstrued as suggesting that these factors have some biological basis. While risk factors are attributes associated with increased likelihood of developing a disease or a health outcome, the presence of a risk factor does not make a particular health outcome inevitable. Many variables affect human health, including genetics and environmental exposures, and there remains much to learn about their interactions and impact on health outcomes.

Based on these examples and evidence, race and ethnicity should never be construed as biological, observed group associations should not be mistaken for causal explanations, and an individual’s race or ethnicity should not be relied upon to predict health outcomes. Despite these potential pitfalls, race and ethnicity can serve several purposes in research—for instance, to ensure adequate rigor with sample populations representing a range of life experience and social contexts, to track health disparities, and to account for how individuals self-identify.

CURRENT USE OF RACE AND ETHNICITY IN BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH

U.S. funders such as the National Institutes of Health often require the use of categories from OMB Statistical Policy Directive 15 to report demographic information about research participants to monitor inclusion in study enrollment. The OMB categories are widely used both by government agencies and by many nongovernmental institutions, such as health care systems. Directive 15 specifies that the categories should not be considered scientific, biological, or anthropological in nature, but sometimes they are used unnecessarily for scientific analysis.

Conclusion 5-1: The OMB categories are a minimum set of categories unique to the United States. The OMB categories are often required for inclusion reporting purposes in research. However,

- the OMB categories are a sociopolitical construct with no biological basis.

- the OMB categories are a minimum set of categories, but federal agencies and the scientific community can collect more detailed information.

- the OMB categories do not need to be used for scientific analysis, even if they are required for reporting recruitment statistics.

Due in part to the emphasis on the OMB categories, the current use of race and ethnicity in research is sometimes seen as an exercise in checking boxes or a matter of using the “right” labels rather than understanding why they are used. However, improving the use of race and ethnicity in biomedical research will require thinking about race and ethnicity with intentionality at every step of the research process and understanding the nuances involved in doing so.

SOUND USE OF RACE AND ETHNICITY DEPENDS ON PERSISTENT ASSESSMENT AND DECISION-MAKING

Decisions about the use of race and ethnicity in biomedical research require careful deliberation. Although some situations may be clear-cut, most are nuanced,6 involving balanced consideration of ethical, contextual, and scientific factors. Even for well-intentioned purposes, such as recruiting a diverse population of participants, the correct approach to using race and ethnicity depends on the research question and the specific context. Context can encompass a variety of biological, social, cultural, behavioral, and environmental factors, including social and historical background that may have contributed to the existing evidence base. In addition, the context varies throughout the research process—from study design, to recruitment, to analysis, and dissemination of results. Therefore, race and ethnicity require ongoing consideration throughout the entire study process to determine whether their use is appropriate or inappropriate.

Conclusion 6-1: Both deciding to use race and ethnicity and deciding to omit race and ethnicity can have advantages and disadvantages in biomedical research. It is important to evaluate potential implications, benefits, and risks not only of using race and ethnicity but also of forgoing collection of these data entirely.

Conclusion 6-2: Addressing the use of race and ethnicity at only one stage of a study fails to capture the unique factors and consequences that can emerge at subsequent steps of the process.

Recommendation 1: At every stage throughout the biomedical research process, researchers should scrutinize, evaluate, and decide whether the use of race and ethnicity is appropriate or inappropriate. Researchers should:

- Identify how the historical or social context, including prior uses of race and ethnicity in research, affects the underlying evidence base for the question of interest;

- Use race and ethnicity in ethical ways based on the context and research question, with a principled scientific rationale documented throughout the study;

- Understand the contexts and requirements for partnering with specific populations and communities, which could include American Indian or Alaska Native Tribes and their distinct political status as sovereign nations;

- Consider the benefits of collecting race and ethnicity information for research purposes, including promoting diverse representation and equity when these constructs are not central to the research question;

___________________

6 See discussion in Chapters 3 and 4 about pulse oximetry, race correction, and clinical decision-making tools.

- Refrain from making unsupported inferences from the analysis, such as relying on race and ethnicity as causal attributes that drive biomedical research outcomes in individuals; and

- Weigh the potential implications, limitations, benefits, or harms of using or not using race and ethnicity.

In publications, researchers should articulate their decisions about whether and how to use race and ethnicity in their research studies and reflect on the outcomes.

RIGOROUS METHODS TO STRENGTHEN SCIENTIFIC INQUIRY ABOUT RACE, ETHNICITY, AND RELATED CONCEPTS

Race or ethnicity has often been used as a proxy for concepts or variables that may be more precise or better suited to the scientific line of inquiry (Box S-1). This reliance on race and ethnicity, especially the OMB categorization, collapses multidimensional information about people into simple labels, making it challenging to tease apart nuanced mechanisms of interest. Furthermore, using race and ethnicity as interchangeable terms exacerbates confusion among researchers and the public. However, avoiding conflation and identifying more targeted approaches can reveal more dynamic and meaningful information. For example, such concepts as structural racism and social determinants of health reveal how broader social contexts have consequences for everyone’s health. As another example, race and ethnicity have sometimes been relied on to capture unspecified variation, and further investigation into biomarkers, physiological mechanisms of action, and environmental factors may better explain observed differences and phenomena in biomedical research.

BOX S-1

Concepts Related to Race and Ethnicity

Race and ethnicity categories are often used as proxies for the true concepts or variables of interest. In addition to self-identified race and ethnicity, researchers may choose to investigate:

- Relational aspects of race

- Structural racism

- Social determinants of health (e.g., environment)

- Ethnic and cultural practices (e.g., language, religion)

- Immigration status and degree of acculturation

- Indigeneity

- Skin color and pigmentation

- Known ancestry

- Genetic markers, genetic variation

- Social and stress-related biomarkers

- Other biomarkers and biological indicators

Conclusion 6-5: Race and ethnicity conflate many concepts and collapse multidimensional information about people’s experience and identity. There is a need for disaggregation of related concepts and for increased granularity in the data collected to better capture the information for which race has been a proxy. Greater methodological specificity will be required to disentangle the various concepts that are often collapsed into a single “race or ethnicity” descriptor or variable.

Decisions to use race and ethnicity should uphold scientific validity, given the research question of interest. It is important to consider whether race and ethnicity are best suited to the scientific purpose or whether another measure might better address the question. Since race and ethnicity can be measured in various ways, as can other related concepts,7 reporting definitions and methodology clearly will be essential as more of this work is undertaken.

Recommendation 2: Whether conducting primary research or secondary data analysis, biomedical researchers should provide an operational definition of race and ethnicity, if used, in all grant applications, manuscripts, and related products. Within these products, researchers should explain their rationale and the limitations of their approach as well as describe attributes of data provenance, such as:

- Which race and ethnicity categories were used for enrollment and/or scientific analyses and why (e.g., which version of the Office of Management and Budget categories was used);

- How race and ethnicity data were reported (e.g., self-identified or socially assigned);

- When data were collected;

- Whether any subcategories were aggregated, including whether samples were relabeled, combined, or harmonized across various sources;

- Whether any race and ethnicity data were derived (e.g., imputation, estimation), and how; and

- Whether bias may exist due to the way categories were defined and handled (e.g., sampling, classification, method of data collection, completeness of data).

Recommendation 3: Researchers should operate with transparency at every stage in the development, application, and evaluation of biomedical technology that may influence health (e.g., clinical algorithms, artificial intelligence [AI] models and tools, medical devices). Researchers should assess and report the performance of biomedical technology across a range of racial and ethnic groups.

___________________

7 See Chapters 5 and 6 and Table 6-1 for more information about race- and ethnicity-related concepts and ways to measure them in research contexts.

Recommendation 4: Researchers should strive to identify which concepts often conflated with race or ethnicity (e.g., environmental, economic, behavioral, and social factors, including those related to racism) are relevant to their study. Based on those concepts, researchers should select applicable measures and do the following:

- Researchers should not rely solely on self-identification with OMB race and ethnicity categories.

- To the greatest extent possible, researchers should incorporate multiple measures in study design, data collection, and analysis to allow for comparison or combination.

- If using a single measure, researchers should articulate a clear scientific justification for why it was chosen and discuss its limitations.

As specified in Recommendation 1, in addition to thoughtfully selecting variables for study design and analysis, care should be taken when interpreting and reporting results to avoid making misleading or unsubstantiated conclusions. In general, race and ethnicity cannot be isolated as independent variables in an experimental setting in biomedical research. Therefore, race and ethnicity can be correlated with an outcome, but the constructs did not cause the outcome. Even so, sometimes results are misattributed to race and ethnicity, and it is important to be aware of limitations surrounding these constructs in biomedical studies.

PRACTICAL APPROACHES TO ACHIEVE INCLUSION THROUGHOUT THE RESEARCH PROCESS

Some research participants are left out of research analyses due to missing race or ethnicity data or because none of the available categories reflects their identity. Others are excluded due to small group sizes or because they selected multiple race and ethnicity categories, making their data more challenging to analyze. There is no single best practice for analyzing data from people who are members of small populations or are multiracial, but the research question and context can guide methodological decisions. Moreover, it is worth considering methods that retain as much information about individuals as possible. Since much of the existing evidence base excludes data that are difficult to work with, there is a need for more research in this area.

Conclusion 6-6: Many people are left out of research analysis either due to missing data or because none of the available categories reflects their background. More granular categories may be aggregated, potentially obfuscating missing data or a misalignment of participants’ identities with the available categories. “Other” is a category label sometimes used to aggregate data—combining race and ethnicity categories that are too small for separate analysis, individuals with missing data, and individuals who do not identify with the available race and ethnicity categories.

Conclusion 6-7: There is an increase in multiracial identification in the United States, but there is no standard way to account for multiracial or multiethnic people in biomedical research. Even if they are recruited, many people who are multiracial or multiethnic are left out of analysis, often because of small sample sizes or uncertainty about how to conduct the analysis. There is a need to include people with mixed ancestry or multiple identities in biomedical research and to appropriately incorporate them in analysis to the greatest extent possible to ensure a diverse sample population.

Recommendation 5: At each stage of the research process, all racial or ethnic category inclusions and exclusions should be based on a clear scientific rationale motivated by the research question.

Researchers should:

- Consider oversampling for smaller populations to ensure adequate power for analysis.

- Describe and characterize all recruited populations, even if some cases cannot be included in analysis due to limits of small sample size.

- Articulate the purpose of aggregating categories, deriving missing data, or omitting cases.

- Use aggregate category labels that are motivated by the research question (e.g., “Members of minoritized racial and ethnic groups”) or reflect the analytical approach (e.g., “Remaining participants”).

- Justify the choice of reference population.

Researchers should not:

- Combine categories solely to improve statistical power.

- Make inferences about residual categories.

- Aggregate participants into the nonspecific categories “Other” or “non-White” because these labels can be isolating and reinforce one category as the norm.

Recommendation 6: Researchers should consider the inclusion and analysis of multiracial and multiethnic participants at each stage of the research process, especially when developing research questions and designing the study. Throughout the course of a study, researchers should:

- Identify relevant concepts (e.g., ancestry, self-identification);

- Ensure that respondents can select multiple races, ethnicities, or ancestries during data collection;

- Report granular data for multiracial or multiethnic respondents to the greatest extent possible, while respecting confidentiality concerns; and

- Identify a plausible classification scheme for including multiracial and multiethnic people in analysis, based on the research question or context; or provide a comparison of results using alternate approaches.

In line with broader community-engagement efforts, the committee emphasizes partnering with communities to understand how race, ethnicity, and related concepts affect people’s experiences. Collaborative engagement at every stage of the research process is essential to doing this work in alignment with ethical and scientific principles.8 However, the most suitable type of engagement depends on the type of study, line of scientific inquiry, and community context. For example, biomedical studies that emphasize social aspects have a higher need for community partnership than basic science studies about biological questions (e.g., analyzing a biological mechanism, identifying drug targets).

Conclusion 6-8: Basic, preclinical, and proof-of-concept studies that seek only to interrogate a biological mechanism can, but need not, invoke questions of race and ethnicity. Regardless of this choice, representing human biological diversity, including in early-stage research, is essential to assure generalizability. Biomedical studies that involve human populations and that hold social and clinical implications necessitate a high degree of cooperative community engagement or partnership.

Forming partnerships with community leaders and members requires patience, time, funding, and expertise. Early on, study teams should incorporate the necessary expertise, including experts in community engagement or community leaders and liaisons. Community members can provide valuable input throughout a study, from development of research questions to collection and analysis of race and ethnicity data and dissemination of results. It is important for the study timeframe to account for the steps and time required for successful community outreach. Considerations for building community partnerships should be embedded at each stage of the research process to customize the use of race and ethnicity based on the study and community context. For instance, American Indian or Alaska Native Tribes have a unique legal status as sovereign nations in the United States, so conducting research with a Tribe may require demonstrated understanding of its history and entails unique requirements for institutional review board approval, data sovereignty, and dissemination of results.

Recommendation 7: Researchers collecting and using race and ethnicity data in biomedical research with human populations should identify and partner with specific communities relevant to the research context. Researchers should collaborate with community engagement experts and organizations and, to the greatest extent possible, partner directly with community members to optimize authentic, continuous, and sustained researcher-community member engagement undergirded by mutual trust.

- From the earliest stages of the project, these partnerships should be established to inform hypothesis development and study design, including how race and ethnicity information should be collected and used, through results interpretation and dissemination.

___________________

- Research teams should communicate potential benefits to community partners from project initiation through results dissemination.

- In the case of secondary data use, researchers should consult documentation or original investigators from participating studies to understand how communities were involved in the process.

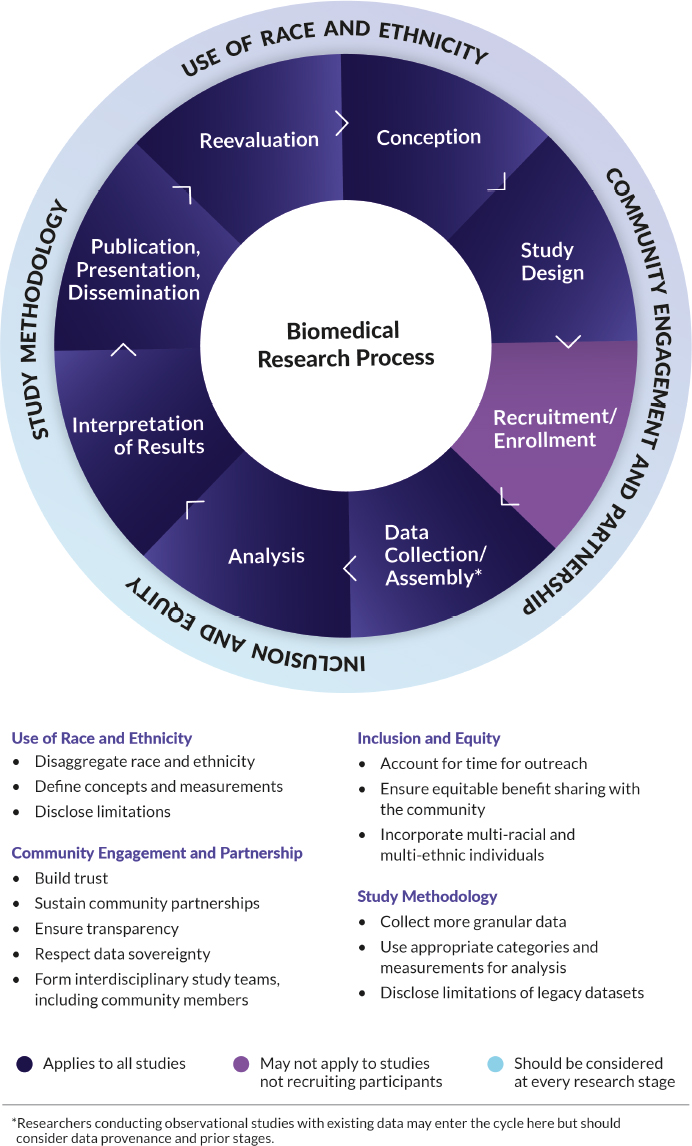

VISUAL SUMMARY

As this report emphasizes, race and ethnicity must be addressed in an ongoing manner. To help researchers operationalize these recommendations, the committee identified four key considerations to bear in mind at each stage of the research process (Figure S-1):

- Assessing whether to include race and ethnicity and, if so, how to use them.

- Forming enduring partnerships with communities.

- Ensuring inclusion and equity for everyone involved in the study and those most affected by the study results.

- Recognizing and characterizing data biases and limitations.

LOOKING FORWARD

This report offers ways to change how race and ethnicity are used, analyzed, and reported in biomedical research. When implemented, these changes have the potential to improve the scientific rigor of biomedical research, mitigate bias that continues to affect research and health care, and build lasting trust among the scientific community and racial and ethnic communities. As this report underscores, appropriate or inappropriate use of these concepts is context dependent. Adopting these recommendations will require coordinated efforts and investment across the biomedical research ecosystem. Addressing the complex issues inherent in how to use race and ethnicity thoughtfully in biomedical research will require sustained, in-depth conversations across disciplines and sectors. It will take time and effort to unlearn old thought patterns and to retrain the workforce with new ways of thinking. Key sectors, such as biomedical journal editors and funders of biomedical research, could help cultivate intentionality, ensure accountability, and catalyze change for the better.

Recommendation 8: Funders, sponsors, publishers, and editors of biomedical research should provide consistent guidelines to assist researchers in developing and examining their work and to promote the thoughtful use of race, ethnicity, and related concepts to enhance adoption of these recommendations.

- Journal publishers and editors, research funders, and sponsors should require researchers to provide a scientific rationale for their use of race and ethnicity, describe data provenance, and acknowledge limitations of their use.

- Journal editors and funding agencies should provide reviewers with specific guidelines for reporting race and ethnicity that should be used to assess publication and funding decisions.

- Funders of research to develop health technologies should require researchers to report results across racial and ethnic groups and encourage researchers to provide datasets, algorithms, and code in an open-source format to the greatest extent possible.

Funders, sponsors, publishers, and editors of biomedical research should periodically evaluate their policies on the use of race and ethnicity to assess the extent to which the policies are followed and upheld, monitor progress, consider the need for updates, and ensure the guidelines reflect current best practices.

Recommendation 9: To support partnerships between communities and research teams, funders and sponsors should require as appropriate a community engagement plan as part of the application. Funders should provide resources and timelines that encourage researchers to build and sustain collaborations. Research institutions, medical centers, and other biomedical research organizations should develop and support lasting, equitable relationships with community partners.

The report represents a vision of the future where the biomedical community moves beyond the limits of focusing on race to adopt practices that will facilitate an understanding of the true factors of disease.

Conclusion 6-12: The biomedical research enterprise has long emphasized race at the expense of exploring other concepts such as racism and discrimination that may have more direct effects on health. Much of the existing evidence base has deep-rooted bias and requires reexamination. Rebuilding the evidence to examine the role of racism and other associated concepts beyond race and ethnicity categories will require investment from funders and sponsors of biomedical research.

Moving forward starts with recognizing and acknowledging assumptions, biases, and flaws in the existing evidence base. Yet making progress does not have to be daunting. It is an exciting time for the biomedical research community to chart a path forward to improve the use of race and ethnicity for better science and better health.