Progress Toward Restoring the Everglades: The Tenth Biennial Review - 2024 (2024)

Chapter: 3 Applying Indigenous Knowledge in the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan

3

Applying Indigenous Knowledge in the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan

The National Academies’ Committee on Independent Scientific Review of Everglades Restoration Progress is charged with discussing scientific and engineering issues that may impact progress toward restoring the Everglades (see Chapter 1). In 2021, the Executive Office of the President released a memorandum on Indigenous Knowledge and its role in federal decision making (EOP, 2021c) and subsequently issued guidance to federal agencies on “considering, including, and applying Indigenous Knowledge in Federal research, policies, and decision making” (EOP, 2022a). Based on specific suggestions from Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) agencies, the committee examines the application of Indigenous Knowledge in the CERP in this chapter and opportunities to improve its inclusion as part of the committee’s charge to address scientific issues that could affect progress toward restoring the natural system and Indigenous peoples’ reciprocal relationship with it (i.e., biocultural restoration).

The committee begins with a discussion of the place of the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida (hereafter the Miccosukee Tribe) and the Seminole Tribe of Florida (hereafter the Seminole Tribe) in the Everglades and the importance of the Everglades ecosystem to their cultures. Incorporation of Indigenous Knowledge into restoration planning and management requires active and effective Tribal consultation and engagement. Therefore, the current regulatory and policy context for state and federal Tribal consultation is presented, followed by an evaluation of the recent history of Tribal consultation and engagement. Indigenous Knowledge and its value to existing Everglades science and management is discussed, along with opportunities for improving the inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in CERP processes. Finally, best practices for Tribal consultation and engagement with Indigenous Knowledge are presented based on recent practices initiated by the Miccosukee Tribe and experiences elsewhere in Indian Country.

Information for this chapter was gathered through public meetings, analysis of primary literature, and interviews with leaders and staff of the Miccosukee Tribe. The Seminole Tribe did not engage directly with the committee during this cycle, although available Tribal correspondence to CERP agencies regarding several projects was reviewed. As a consequence, this chapter draws heavily upon responses from and engagement with the Miccosukee Tribe.

PLACE OF MICCOSUKEE AND SEMINOLE TRIBES IN THE EVERGLADES AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE TO THEIR LIVELIHOODS AND CULTURES

The Florida Everglades is the unceded homeland of the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes. Both Tribes have a deep and unique relationship with the lands, waters, biota, and ecosystem processes that make up the greater Everglades. For generations the Everglades has been an integral part of their spiritual, cultural, political, economic, and familial social fabric. The Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes have persisted in their homelands throughout brutal waves of European colonization and control of Florida by the U.S. government, three significant wars, numerous failed or broken treaties, land seizure, forcible removal in the 1800s, and displacement from their homes by increasing settlement and housing development. The Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes originated as members of the Muscogee Creek of Alabama, Georgia, and northern Florida, with ancestral ties to the Calusa people and other Native American Tribes, who moved south beginning in the early 1700s, replacing other Native people who did not survive the earlier incursions of Europeans into Florida. Both Seminoles and their Muscogee Creek ancestors were among those forcibly moved to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears in the 1830s (Sturtevant and Cattelino, 2004).

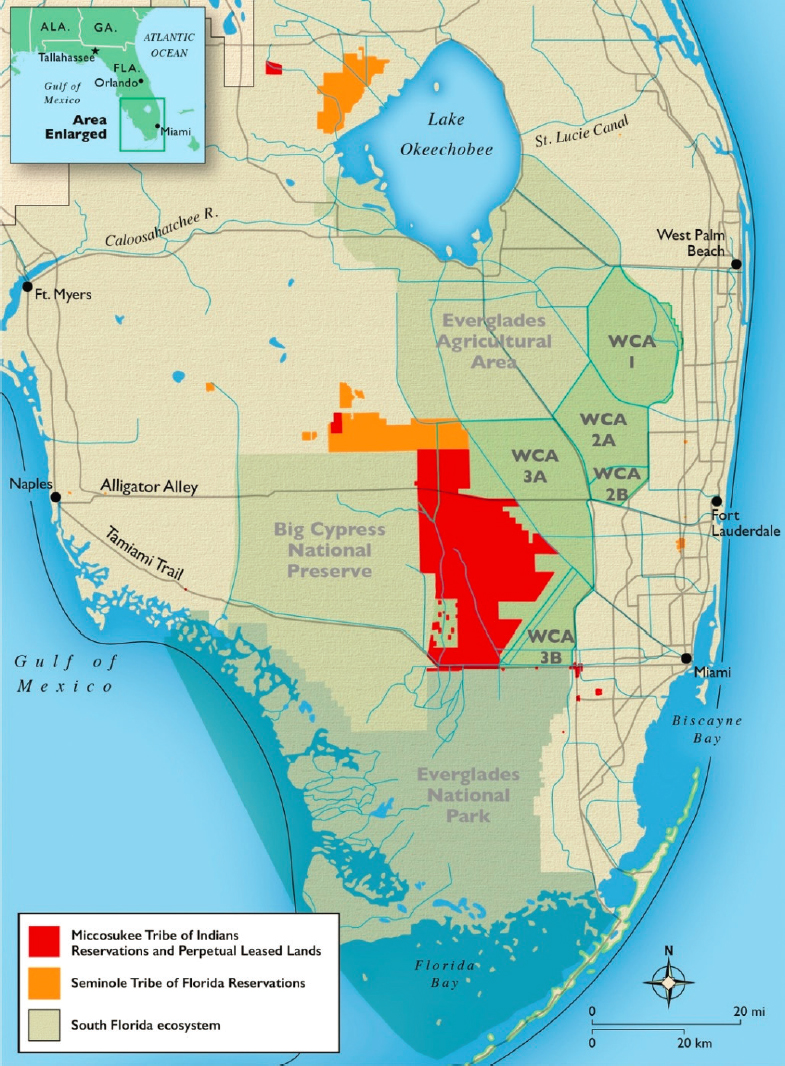

Once occupying lands throughout southern and central Florida, the Seminole and Miccosukee Tribes now inhabit a fraction of their historical homelands. The Seminole Tribe is now scattered across six spatially disjunct small reservations in South Florida—Big Cypress, Brighton, Fort Pierce, Hollywood, Immokalee, and Tampa Reservations—totaling approximately 90,000 acres.1 The Miccosukee Tribe has four reservations in south central Florida totaling a land area of approximately 75,000 acres—the Alligator Alley Reservation, Tamiami Trail Reservation, and two small Krome Avenue Reservations.2 The Miccosukee Tribe also holds a perpetual lease to 189,000 acres of Water Conservation Area 3A (WCA-3A) (Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida v. U.S., 656 F. Supp. 2d 1375, 1378 [S.D. Fla. 2009]; Godfrey and Catton, 2011) (Figure 3-1). Both Tribes are permitted “to continue their usual and customary use and occupancy of Federal

___________________

1 See https://www.semtribe.com/history/seminoles-today.

2 See https://r4data.response.epa.gov/r4rrt/miccosukee-tribe.

SOURCE: Map by International Mapping.

or federally acquired lands and waters within the [Big Cypress National] preserve and the Addition,3 including hunting, fishing, and trapping on a subsistence basis and traditional tribal ceremonials” (16 U.S.C.A. §698, West 2010; Prior, 2013). In 1957 and 1962, the Seminole and Miccosukee Tribes, respectively, gained formal recognition from the United States, thus legally establishing their status as sovereign, domestic dependent nations (Adams, 2016).

The Everglades represents a major part of the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes’ identities as a location for spiritual, traditional, kinship, and cultural connections and activities, including use of native plant and animal foods (Carr, 2002; Sturtevant and Cattelino, 2004), and this connection is passed from generation to generation. Through lived experience and intergenerational oral traditions, the Tribes of the Everglades acquire and preserve knowledge, cultural legacy, and traditions with storytelling, song, and performance—practices that continue to this day (Fixico, 2017; Jackson, 2014; LeBrasseur and Freark, 1982; Sturtevant and Cattelino, 2004).

The Significance of Everglades Tree Islands to the Tribes

Although there are many issues and aspects of Everglades restoration that are of concern to the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes, such as water quality, habitat degradation, and the impacts of invasive species, tree islands are particularly illustrative because of their significance to the Tribes. Tree islands are topographical features in the Everglades formed by geomorphological processes. Most tree islands in the Everglades are elongated islands oriented with a long axis that follows historical water flow patterns (Sklar and van der Valk, 2002). Tree islands are characterized by woody vegetation on the upstream portion that is intolerant to prolonged inundation (Figure 3-2). In contrast, peripheral and downstream portions of tree islands are often occupied by vegetation tolerant of intermediate and longer hydroperiods (Sklar and van der Valk, 2002). These unique features of tree islands, along with their tendency to be nutrient sinks, contribute to their high plant diversity (Heisler et al., 2002; NRC, 2012) and diverse invertebrates and wildlife, including birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians (Meshaka et al., 2002). Tree islands are important to ecosystem processes and biodiversity, and they are among the most vulnerable landscape features of the Everglades to hydrological changes caused by decades of adverse water management practices.

For centuries, the Native peoples of the Florida Everglades—Seminoles, Miccosukee, and those that dwelled there before them—have held deep connections to tree islands. The significance of tree islands to the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes cannot be overstated. Tree islands within the Everglades

___________________

3 The “Addition” refers to the expansion of the Big Cypress National Preserve by about 146,000 acres in 1988. See https://www.nps.gov/bicy/learn/management/addition-lands-gmp.htm.

NOTE: Tree islands are embedded in a matrix of sawgrass plains and ridges, emergent marshes, and deepwater sloughs.

SOURCES: Courtesy of D. Kilbane; Wetzel et al., 2005.

have supported every aspect of Seminole and Miccosukee peoples’ lives. Tree islands have provided places to grow a variety of crops and find food, medicines, and materials for shelter and canoes, which historically provided not only a means of subsistence but also trade and self-determination in the region (Goss, 1995; Sturtevant and Cattelino, 2004). They also provided critical refuge and protection against disease, slavery, massacre, and expulsion by European colonizers and the U.S. government (and allies), and later as retreat from displacement by development of the southeast coast of Florida (Covington, 1993; Cypress, 2023; Reséndez, 2016; Sturtevant and Cattelino, 2004). It is not an exaggeration to say that the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes would not exist in Florida today were it not for the safe harbor tree islands provided deep within the Everglades.

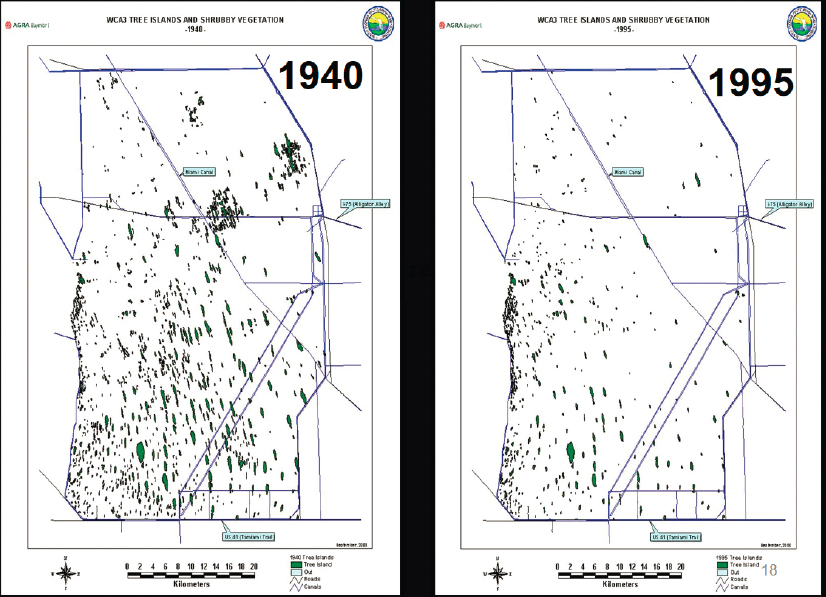

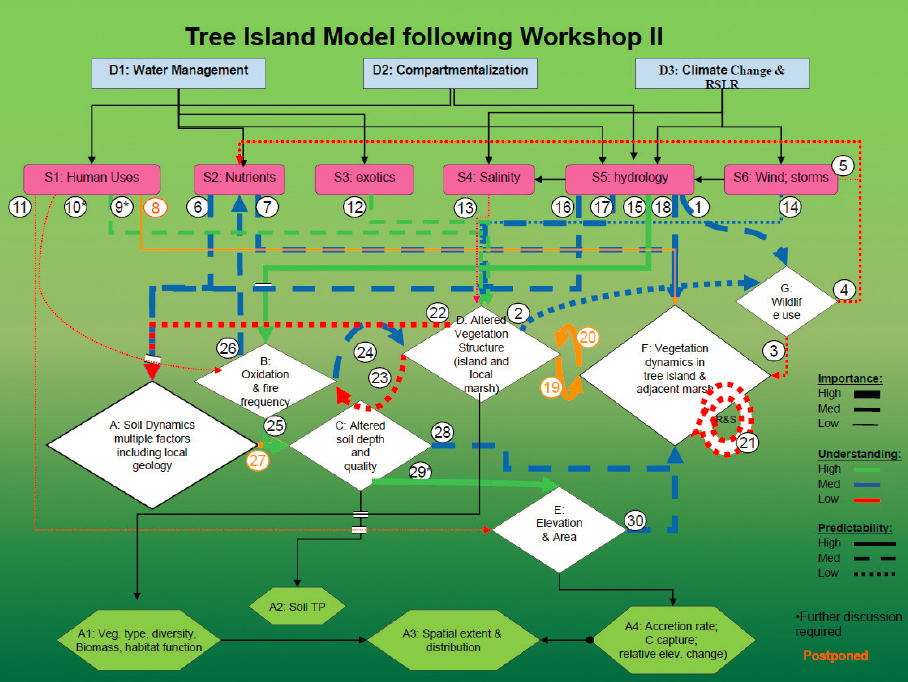

Tree islands are sensitive to changes in water depth, flow, quality, and hydroperiod; altered fire regimes; and invasive species, and they have been severely degraded by prolonged dry and wet hydrologic extremes (Box 3-1 and Figure 3-3). At least 70 percent of tree island land cover has been lost from the Everglades since 1940 (Sklar and van der Valk, 2012; Sklar et al., 2005), and the

BOX 3-1

Drivers of Tree Island Loss

Water management over the past 60 years caused the northern part of WCA-3A to become drier, increasing peat subsidence and fire intensity and frequency, which has led to reduced tree island elevations and tree island loss (Wetzel et al., 2005). Accordingly, much of the tree island acreage in northern WCA-3A has been lost, and because of subsidence, some remaining tree islands have experienced greater inundation during wet weather, alterations in vegetation, and reduction in biodiversity (Sklar et al., 2005). Tree islands in the northern parts of WCA-3A have increased vulnerability to fires because of their drier conditions (Cypress, 2023; NRC, 2010). In contrast, tree islands in the southern areas of WCA-3A experience higher water depths, longer hydroperiods, and ponding. These higher water depths have drowned hardwood species, shifted vegetation to more flood tolerant species, and reduced wildlife (Sklar et al., 2005). Most of these losses will require decades to centuries to recover ecological function under ideal conditions (NRC, 2012).

NOTES: Losses have been attributed to fires, subsidence, or extreme high or low water levels. Almost all remaining tree islands occur in WCA-3, Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge, and Everglades National Park.

SOURCE: https://apps.sfwmd.gov/ci/publicmeetings/viewFile/26687.

spatial extent of tree islands in WCA-3 declined by 61 percent between 1940 and 1995 (Patterson and Finck, 1999). The remaining tree island distribution overlaps significantly with the Miccosukee Tribe’s reservations and current lease holdings in WCA-3A (Figures 3-1 and 3-3).

The degradation and loss of tree islands have had profound impacts on the Miccosukee Tribe. By 1960, the last family still living on the tree islands was forced to move because of uninhabitable conditions (Cypress, 2023). The Miccosukee Tribe notes that sloughs south of Tamiami Trail have become overrun with grasses and sedges due to water impoundment in WCA-3A, compounded by invasive plant species and elevated nutrients in inflows, preventing navigation by canoe and isolating Miccosukee villages in this region. Flooding has reduced opportunities for hunting as wildlife diversity decreased, and it has also interrupted the practice of ceremonies and cultural activities (Cypress, 2023).

Living in and relying on the Everglades in a deeply connected way offers unparalleled understanding of the ecosystem. The Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes’ empirical knowledge and comprehensive understanding of the ecosystem is drawn from their history, current life experiences, and cultural practices. This connection to the landscape as a way of being provides the basic foundation of Indigenous Knowledge. If applied to restoration planning, monitoring, and management, Indigenous Knowledge could enhance restoration outcomes for Tribes, CERP agencies, and stakeholders alike. Careful consideration of Tribal connections to the land and their knowledge of the ecosystem will help achieve a more holistic biocultural restoration of the Everglades, in which the biophysical and sociocultural components of the ecosystem are recognized as interdependent and reciprocal (Lyver et al., 2016; Sena et al., 2022; Winter et al., 2020). Reciprocity is a cornerstone of Tribal identity and lived experience. In short, reciprocity refers to “the Earth, understood as a constantly renewing source of gifts, [and] humans having a responsibility to reciprocate for all they have been given” (Kimmerer, 2017).

In this light, an ongoing practice of meaningful engagement is necessary for effective inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in the restoration process. In the following sections, the committee reviews the legal requirements for Tribal collaboration and consultation, reviews the recent history of collaboration, and offers context and recommendations for meaningful engagement on tree island restoration.

COLLABORATION WITH EVERGLADES TRIBES

In this section of the report, the committee describes the responsibilities for collaboration between state and federal governments with Tribes as well as the history and means of collaboration. Consultation between the lead CERP

agencies—the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD)—and the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes is emphasized, while noting that other federal agencies also have Tribal trust responsibilities and play a role in the CERP.

State Duties to Consult

CERP authorizing and implementing legislation obligates the State of Florida and its agencies involved in restoration to consult with the Tribes (discussed further in the next section). A unique relationship between the SFWMD and the Seminole Tribe was established by a Water Rights Compact that was approved by Congress and ratified by the Florida Legislature in 1987 as part of the Seminole Indian Land Claims Settlement Act of 1987 (Public Law 100-228). The Water Rights Compact of 1987 ensures Tribal water rights and establishes rules and authorities for managing water quality and quantity on Seminole lands (Shore and Strauss, 1990). To date, there is no similar agreement between the State of Florida and the Miccosukee Tribe.

Federal Duty to Consult and Protect

Since 1831,4 federal law establishes that the U.S. government has a trust responsibility to Indian Tribes. Although the trust responsibility has often been ignored, the courts have clearly stated that it consists of “the highest moral obligations that the United States must meet to ensure the protection of tribal and individual Indian lands, assets, resources, and treaty and similarly recognized rights” (DOI, 2014). The CERP authorizing legislation under the Water Resources Development Act of 2000 (WRDA 2000; Public Law 106-541) identified responsibilities and consultation requirements throughout the restoration process for the state and federal agencies. WRDA 2000 noted that “tribal lands designated and managed for conservation purposes, as approved by the tribe” were part of the natural system inclusions in the CERP. The CERP authorizing legislation also stated that with respect to the restoration, “the Secretary of the Interior shall fulfill his [sic] obligation to the Indian tribes in South Florida under the Indian trust doctrine as well as other applicable legal obligations.” The CERP required the Secretary of the Army to consult with both Tribes in the promulgation of programmatic regulations and stated that nothing in the authorizing legislation would impact existing water rights or existing legal sources of water for the Tribes (Box 3-2).

___________________

4 Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. 1, 16 (1831).

BOX 3-2

Consultation Rights of Tribes of South Florida

Five Tribes have rights to consultation and coordination as a result of their ancestral links to the Florida Everglades: the Miccosukee Tribe, the Seminole Tribe, Thlopthlocco Tribal Town, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and the Muscogee (Creek) Nation (C. Thomas, USACE, personal communication, 2023). The latter three were removed from the region but maintain active interest in the Florida Everglades. The Miccosukee Tribe and Seminole Tribe currently reside in a portion of their Everglades homelands and were the sole Tribes to be explicitly included in WRDA 2000 and the Programmatic Regulations. Like all federally recognized Tribes, the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes are independent, sovereign nations that enjoy a government-to-government relationship with the U.S. federal government; they are not simply another stakeholder group. The two Tribes have distinctive language, cultures, governance, and Indigenous Knowledge.

The Programmatic Regulations (FR 66 No. 218) established the requirement for the USACE and the SFWMD to consult with the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes (and other agencies) as they implement the CERP “to achieve and maintain the benefits to the natural system and human environment described in the Plan.” This consultation encompasses changes to water reservations; the development of System and Project Operating Manuals, the adaptive management program, and a master sequencing plan; the periodic “evaluation of the Plan using new or updated modeling that includes the latest scientific, technical, and planning information,” known as the Periodic CERP Update; modifications to the Plan; and reports to Congress. RECOVER, as the coordinating office for the adaptive management program, is required to follow federal and state responsibilities and consult with the Tribes on documents or work products. Consultation with Tribes is defined in the Programmatic Regulations as follows:

In addition to any other applicable provision for consultation with Native American Tribes, including but not limited to, laws, regulations, executive orders, and policies the Corps of Engineers and non-Federal sponsors shall consult with and seek advice from the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida and the Seminole Tribe of Florida throughout the implementation process to ensure meaningful and timely input by tribal officials regarding programs and activities covered by this part. Consultation with the tribes shall be conducted on a government-to-government basis.

The implementing regulations require the USACE and the SFWMD to encourage participation of the Tribes (and other agencies) on Project Delivery Teams and on RECOVER.

Aside from CERP-specific authorities and regulations, executive orders have also established various terms for federal agencies to consult with Tribes that affect Everglades Restoration and the many federal agencies involved. Executive Order 13175 (EOP, 2000) was issued “to establish regular and meaningful consultation and collaboration with tribal officials in the development of Federal policies that have tribal implications, to strengthen the United States government-to-government relationships with Indian tribes, and to reduce the imposition of unfunded mandates upon Indian tribes.” These requirements and responsibilities for consultation obligate every federal agency action that may impact Tribal resources, which can include resource management activities of the U.S. Department of the Interior agencies (National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [FWS], Bureau of Indian Affairs); other federal agencies such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and others as directed by the federal government.

Recent executive directives emphasized the value of Indigenous Knowledge as an important element of the federal Indian trust responsibility (Box 3-3). In 2022, a memorandum from the Executive Office of the President (EOP, 2022a) called upon federal agencies to “pursue and promote inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in Federal scientific and policy decisions . . . including Tribal consultation action plans” (The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, 2022). Accompanying implementation guidance (EOP, 2022b) was provided to assist agencies “in (1) understanding Indigenous Knowledge, (2) growing and maintaining the mutually beneficial relationships with Tribal Nations and Indigenous Peoples needed to appropriately include Indigenous Knowledge, and (3) considering, including, and applying Indigenous Knowledge in Federal research, policies, and decision making” as outlined in the initial guidance (EOP, 2022a; The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, 2022). The Executive Office of the President (EOP, 2022b) notes that Indigenous Knowledge is a valid form of evidence that can be a source of accurate information, valuable insights, and effective practices. These executive directives apply to all the work of the USACE and other federal agencies working on Everglades Restoration.

ASSESSMENT OF CERP TRIBAL CONSULTATION AND COLLABORATION OVER TIME

Consultation and coordination with Tribes have been part of the Florida Everglades Restoration Project mandate from its inception. However, it has not always been honored. The volume and focus of lawsuits brought by the Tribes early in CERP planning and implementation are an indication of the adverse consequences of lack of consultation and failure to include Tribal needs, perspectives, and

BOX 3-3

Executive Orders and Memoranda from the Executive Office of the President Relating to Indigenous Knowledge

- Executive Order 13990 (January 20, 2021) on Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis, which recognized the value of traditional knowledge and directed the establishment of a Federal Task Force and Tribal Advisory Council (EOP, 2021a).

- Executive Order 14049 (October 11, 2021) on the White House Initiative on Advancing Educational Equity, Excellence, and Economic Opportunity for Native Americans and Strengthening Tribal Colleges and Universities, which committed to promoting Indigenous learning through the use of traditional ecological knowledge (EOP, 2021b).

- Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) Memorandum (November 15, 2021) on Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge (ITEK) and Its Role in Federal Decision Making, which acknowledges that ITEK is owned by the Indigenous people that collected it (EOP, 2021c).

- Executive Order 14072 (April 22, 2022) on Strengthening the Nation’s Forests, Communities and Local Economies, in which policy was enacted to support Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge and cultural and subsistence practices in our national forests (EOP, 2022c).

- Executive Office of the President Memorandum (November 30, 2022) on Uniform Standards for Tribal Consultation, which established baseline standards across all agencies for consulting Tribal Nations (EOP, 2022d).

- Executive Office of the President Memorandum (December 1, 2022) on Guidance for Federal Departments and Agencies on Indigenous Knowledge, which assists agencies in understanding Indigenous Knowledge, developing relationships with Tribal Nations, and considering, including, and applying Indigenous Knowledge to federal research, policies, and decision making (EOP, 2022a).

- Executive Office of the President Memorandum (December 1, 2022), on Implementation of Guidance for Federal Departments and Agencies on Indigenous Knowledge, which sets expectations for agencies to implement engagement with Tribal Nations, and inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge according to the Guidance (EOP, 2022b).

- Executive Order 14096 (April 21, 2023) on Revitalizing our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All, which stated clearly that Indigenous people were to be recognized for having unique knowledge of their resource and were to be included in decision making to ensure equity in process (EOP, 2023a).

- Executive Order (December 6, 2023) on Reforming Federal Funding and Support for Tribal Nations to Better Embrace Our Trust Responsibilities and Promote the Next Era of Tribal Self-Determination, which in addition to increasing the flexibility and utility of federal funding and support programs for Tribes, orders agency heads to “respect Tribal data sovereignty and recognize the importance of Indigenous Knowledge by, when appropriate and permitted by statute, allowing Tribal Nations to use self-certified data” (EOP, 2023b).

knowledge. Against this background, it is noteworthy that current representatives of the USACE, the SFWMD, and the Miccosukee Tribe each expressed that there is a growing culture of coordination between the agencies and the Tribes.

The USACE Jacksonville District and the SFWMD each employ a Tribal liaison who manages frequent interactions with both the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes. The SFWMD liaison endeavors to interact with the Tribes daily “as neighbors” (A. Ramirez, SFWMD, personal communication, 2023). In addition, the liaison

coordinates regular interactions between Tribal leadership and SFWMD leadership, with a goal of a minimum of two meetings per year. The USACE Tribal liaison interacts extensively with the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes, generally logging multiple contacts per day. The USACE liaison coordinates consultation between USACE and Tribal leadership, as well as scientists and Tribal staff. The USACE Tribal liaison also participates in key events hosted by the Tribes throughout the year and ensures appropriate participation by other USACE staff and leaders (C. Thomas, USACE, personal communication, 2023). Both agency liaisons indicate that effective engagement with the Tribes requires constant commitment to cultivating and maintaining a long-term relationship.

Both Tribes have also had strong support from the Environmental Protection Agency and have successfully gone through the federal administrative process to establish water quality standards for areas in their jurisdiction (EPA, 2024). Notably, the Miccosukee Tribe was the first entity in the State of Florida to establish a numeric nutrient criterion for phosphorus—10 ppb for their Outstanding Waters (Godfrey and Catton, 2011).

In the following section, the committee discusses the evolution of CERP Tribal engagement over time through presentations of three examples: Lake Okeechobee Watershed Restoration Project (LOWRP), Western Everglades Restoration Project (WERP), and operations of the S-12A and S-12B structures. Then, the committee provides a high-level assessment of current consultation and engagement in the context of establishing a necessary foundation for engagement with and application of Indigenous Knowledge in CERP planning and management.

Examples of the Evolution of CERP Engagement

Lake Okeechobee Watershed Restoration Project

The LOWRP is an example of a project that experienced lengthy delays because of poor quality of Tribal engagement and/or lack of serious consideration of Tribal concerns. Although the time frame of this project overlapped with the more positive example from WERP (see next section), the LOWRP differed in its consideration of Tribal input. An early Lake Okeechobee Watershed planning effort began in the early 2000s but was halted in 2006. LOWRP planning was restarted in 2016, and early on in this process, the Seminole Tribe objected to a large storage reservoir near its Brighton Reservation. A draft Project Implementation Report (PIR) was released in 2018 that proposed a shallow 46,000 acre-feet (AF) above-ground water storage feature (termed “wetland attenuation feature”; Figure 3-4) after considering two alternatives with shallow reservoirs near the Brighton Reservation and one deep reservoir

SOURCE: USACE and SFWMD, 2020b.

at a more distant site (USACE, 2024f). The Seminole Tribe voiced numerous objections to this plan, expressing concerns about the proximity of the storage features to Brighton Reservation, potential impacts to cultural resources, potential flooding, and lack of involvement of the Seminole Tribe in project planning when the preliminary alternatives were identified and screened (USACE and SFWMD, 2020b). The Seminole Tribe also expressed concerns that alternative water storage locations were not given due consideration and evaluated equally (Osceola, 2019).

The “Final” PIR was released in October 2020, but the features were essentially unchanged despite these concerns (see Box 3-4 for an overview of major LOWRP decision points and the stated rationale). However, in 2021 under a new administration, the proposed plan was not approved by USACE headquarters “due in part to concerns raised by the Seminole Tribe of Florida” (USACE, 2024f), and efforts refocused on a previously rejected alternative. As of 2024, planning is still ongoing (Box 3-4). The LOWRP is an example of how lack of meaningful engagement with Tribes led to delays in implementation and significantly impacted planning efforts.

BOX 3-4

Evolution of the Lake Okeechobee Watershed Restoration Project

2016: Project planning was launched.

2018: A draft PIR was released that proposed a shallow 46,000-AF above-ground water storage feature (termed “wetland attenuation feature”) located near the Brighton Reservation, 80 aquifer storage and recovery (ASR) wells, and approximately 4,800 acres of wetland restoration (Figure 3-4).

2020: Despite objections by the Seminole Tribe throughout the planning process and explained in a letter to the USACE (Osceola, 2019), the major features of the plan were unchanged. USACE and SFWMD (2020b) stated,

Throughout the LOWRP planning process, the project has been modified based on Tribal and stakeholder feedback to reconfigure the surface storage footprint to avoid direct northern proximity to Brighton Reservation, avoid a known significant cultural site, reduce the depth of the surface storage pool, provide a buffer between the surface storage feature and Brighton Reservation and Tribal lands, and provide a greater buffer for future commercial development along State Road 78 not approved by USACE headquarters. . . . The project will be designed so there are no changes to flood protection caused by the project.

The 2020 PIR also stated reasons why an alternative located farther from the Brighton Reservation was not selected:

1) this alternative is significantly more expensive than the other alternatives, 2) this alternative proposes deep reservoir storage, which increases overall seepage concerns, 3) this location does not allow co-location of the reservoir with ASR wells, which reduces the overall operational flexibility of the reservoir, 4) entire surface storage lands for this alternative are privately owned, increasing impacts on local landowners and increasing overall real estate administrative and acquisition costs, 5) the entire reservoir footprint for this alternative contains potential habitat for critically-endangered Florida grasshopper sparrows, 6) the reservoir in this alternative impacts the largest amount of wetlands of all the alternatives, and 7) the deep reservoir storage in this alternative is less suitable for the growth of wetland vegetation within the reservoir footprint than the other two alternatives that include shallow surface storage.

2021: USACE headquarters rejected the plan, “due in part to concerns raised by the Seminole Tribe of Florida” (USACE, 2024f).

2022: The project was subsequently revised to remove the wetland attenuation feature and reduce the number of ASR wells to 55 (USACE and SFWMD, 2022a,b), but the 2022 PIR was not approved by USACE headquarters “due to concerns with risks posed by the ASR system and the increase in estimated costs” (USACE, 2024f). The planning team was then advised to reconfigure the tentatively selected plan to consider other above-ground storage alternatives, including those previously screened out (USACE, 2024f).

2024: In February 2024, the SFWMD released a Section 203 final feasibility study for the Lake Okeechobee Component A Reservoir (SFWMD, 2024b)—a 200,000-AF reservoir in the same footprint as one of the 2018 draft PIR alternatives that was not selected. The LOWRP PIR is being reconfigured into a fourth revised draft.a

__________________

Western Everglades Restoration Project

WERP represents an example of positive progress toward more effective Tribal consultation. The western Everglades, which covers an area of 1,200 mi2, encompasses the Big Cypress Reservation of the Seminole Tribe of Indians and is bounded by the Miccosukee Tribe reservations to the east and south. As discussed in Chapter 2, the western Everglades has been negatively impacted by hydromodifications from the Central and South Florida Project and high nutrient inflows from upgradient agricultural land uses, resulting in extreme dryness, poor water quality, habitat destruction, and other impacts on Seminole and Miccosukee Tribal lands. In the early 2010s, the Tribes were concerned that substantial efforts were being directed to the Central Everglades Planning Project (CEPP) but CERP planning was not addressing key Tribal concerns in the western Everglades. During the December 2012 meeting of the South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Task Force (Task Force), the Seminole Tribe filed a minority report concerning unmet environmental water needs in the Big Cypress Reservation including poor water quality and insufficient water flows into the Big Cypress Reservation and Big Cypress National Preserve (SFERTF, 2012). The Miccosukee Tribe expressed similar concerns and was particularly concerned about water quality in the L-28 interceptor canal (L-28i) and its impact on WCA-3A, which is designated as Outstanding Miccosukee Waters Tribe, deemed “essential to the survival of the Miccosukee Tribe” (Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, 2021). This 2012 Task Force meeting was an important turning point for Tribal consultation and engagement that launched a concerted effort to advance restoration progress in the western Everglades. A subgroup of the Task Force was established in early 2013 to address the concerns raised by the Tribes, and planning for the WERP began in August 2016 (see Chapter 2 for discussion of WERP progress).

A common theme that emerged in early meetings of the Task Force subgroup was the lack of data and appropriate modeling tools with which to analyze alternatives for the area. Little was known about the hydrology of the western basin, particularly the interactions between surface and ground waters. Existing model boundaries needed to be expanded to analyze alternatives for the region, reflecting a prior lack of priority for restoration of those regions. The Seminole Tribe cited lack of critical data for the studies, and the Miccosukee Tribe noted the need for a data inventory, assessment of data gaps, and a plan to develop better datasets (SFERTF, 2014). The need for data and new analytical tools was noted again in 2016 (SFERTF, 2016).

Since WERP planning began in 2016, both Tribes have been involved in consultation and coordination (USACE and SFWMD, 2023a), and the Seminole Tribe has also been involved as an official cooperating agency under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) (Billie, 2016). Throughout the WERP planning

process, the agencies and the Tribes have actively communicated through dedicated meetings, written communications, and participation at public meetings. Additionally, the draft PIR (USACE and SFWMD, 2023a) outlines a plan to apply Indigenous Knowledge from the Seminole Tribe to determine flows through the S-223 into the Seminole Tribe of Florida Native Area, with the exact details to be outlined in the final Project Operating Manual. Both Tribes have expressed strong support for the WERP tentatively selected plan, as evidenced through their communications to the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Cypress, 2022; Osceola, 2023).

The WERP process has been lengthy and challenging—from the initial Minority Report filed in 2012, to the recently released draft PIR (USACE and SFWMD, 2023a), with the study extended twice since its inception in 2016. Considerable time and effort have been expended to build trust and a well-functioning process between the agencies and the Tribes. Because trust is of paramount importance to this process, both Tribes specifically asked for assurances that their involvement and cooperation throughout the process will not result in land condemnation or Tribal members losing any part of their lands (Cypress, 2020; Osceola, 2020).

CEPP/Combined Operational Plan (COP) Operations

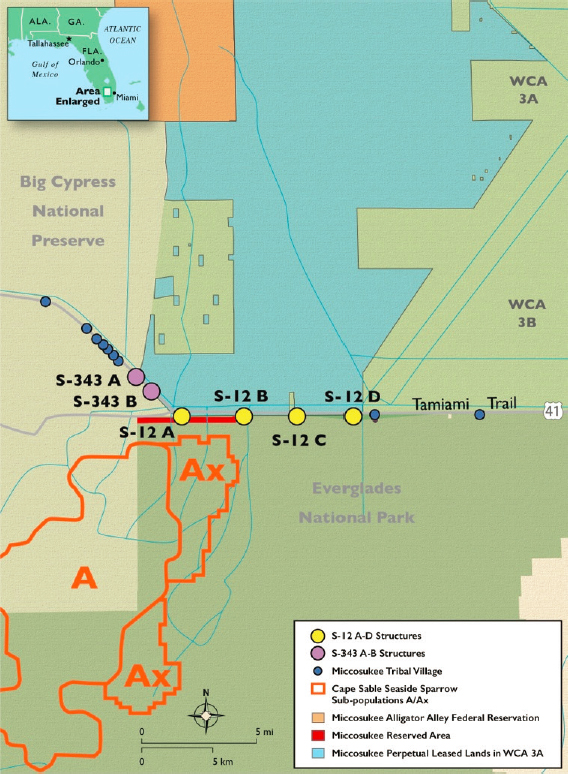

Management of water in WCA-3A has been a source of contention for the Miccosukee Tribe since the 1980s because of its adverse effects on the tree islands that are so fundamental to their culture and identity (Cypress, 2023) (see above; Box 3-1). For the past 25 years contention has especially focused on seasonal closures of the S-12A and S-12B structures through which water flows from southwestern WCA-3A across the Tamiami Trail and into Western Shark River Slough in order to maintain dry conditions for endangered Cape Sable seaside sparrows (Ammodramus maritimus mirabilis) inhabiting the marl prairies adjacent to the slough during their nesting season (Box 3-5). These seasonal closures cause ponding of water in southwestern WCA-3A, exacerbating flooding of tree islands and affecting their native flora and fauna.

Until recently, the Tribe has had no success in affecting a change in the operation of the S-12s or the nearby S-343 structures (Box 3-5) to alleviate this problem, despite persistent attempts. The structures have been opened during the scheduled closures during emergency deviations, but these deviations have been driven primarily by flood control and levee safety (USACE et al., 2023a), and not by the needs of the Tribe for relief from high water. The needs of the sparrow—and avoiding yet another jeopardy opinion for violating the Endangered Species Act—have consistently taken precedent over the needs of the Tribe.

BOX 3-5

Water Management Challenges Affecting Flows into Western Shark River Slough

Prior to the construction of the WCAs in the 1960s, approximately two-thirds of the flow into Shark River Slough came through Northeast Shark River Slough and one-third through Western Shark River Slough (see Figure 2-21 showing distribution of flows). After construction of the WCAs, conditions in Western Shark River Slough became much wetter (90 percent of total flow) and in Northeast Shark River Slough much drier (10 percent of total flow), producing a myriad of adverse ecological effects, including effects on tree islands in WCA-3A (NASEM, 2021).

Attempts to restore the historic distribution of flow, notably the Experimental Water Deliveries Program (1983–1999), had little success (Figure 2-21), chiefly because of flood mitigation constraints protecting residences in the 8.5 Square Mile Area (Las Palmas) that affected flows into Northeast Shark River Slough. The limitations of the water management regime resulted in a crisis when large regulatory releases through the S-12A and S-12B structures into Western Shark River Slough necessitated by high water levels in 1993–1995 nearly extirpated Cape Sable seaside sparrow subpopulation A adjacent to the slough (Figure 3-5). In response to these impacts on the sparrows, FWS issued a Jeopardy Opinion on the Experimental Water Deliveries Program in 1999, effectively ending the program and necessitating new water management (NASEM, 2023).

Subsequently, various operational plans governed water management at the boundary of WCA-3A and Everglades National Park from 2000 to 2016, all of which included seasonal closures of S-12A and S-12B, as well as S-343A, -343B, and -344, through which water in southwestern WCA-3A can be released into the Big Cypress National Preserve (Figure 3-5), in order to ensure that sparrow habitat is suitably dry during their (March to mid-July) nesting season. Subject to the same constraints that plagued previous water management efforts, these plans had little success in redistributing flow in Shark River Slough (Figure 2-21) or protecting sparrows. FWS issued a Jeopardy Opinion on the impact of the last of these, the Everglades Restoration Transition Plan (2012-2016), because of its impact on the sparrows (FWS, 2016). With limited capacity to convey water into Northeast Shark River Slough, closure of the S-12s and S-343s resulted in increased water levels in southern WCA-3A during wet conditions.

The COP, which was fully implemented in 2020, has made progress moving flows from Western to Northeast Shark Slough (Figure 2-21), but seasonal closures remain in place under the COP. Under baseline COP operations, S-12A and S-12B and the S-343s are generally closed October 1 and are not re-opened until the sparrow nesting season ends in mid-July. However, under specified conditions S-12A can remain open until November 1, and S-12B until December 1 (USACE, 2020a). Deviations to this schedule have occurred in 2020 and in 2023 under the COP (USACE et al., 2023a), as they did under the various operational plans in effect during 2000–2016.

SOURCE: Map by International Mapping.

However, the most recent deviation has been different. In fall 2023, heavy rains in September created high-water conditions in WCA-3A, flooding tree islands. Following up on an earlier letter that articulated the Tribe’s Indigenous Knowledge relevant to the adverse impacts of the seasonal closures (Cypress, 2023), vetted through the Tribe’s peer-review process (Ornstein, 2024; see below), in October 2023 the Tribe appealed to the FWS to allow the gates to be opened. Although levels did not reach those that trigger discharges under the COP, or create wildlife emergency conditions, as in past emergency deviations, forecast models indicated that these levels were likely to be reached in the near future. Additionally, no sparrows had been detected in habitat adjacent to Western Shark River Slough since 2018. The USACE proposed a planned temporary deviation, and the FWS responded to the Tribe indicating they would support it (L. Williams, 2023). A planned temporary deviation was declared and the S-12A, -12B, -343A, and -343B structures were opened in November 2023, with provisions to open them again under specified conditions through the remainder of the seasonal closure period, through July 14, 2024 (Ehlinger, 2023).

Tribal engagement and consideration of Indigenous Knowledge played an important role in the decision to proactively open the S-12 and S-343 structures to address high-water conditions (G. Ralph, USACE, personal communication, 2024). The Tribe provided a wealth of relevant information prior to the event (Cypress, 2023), and it is clear that the Tribe was highly engaged in the decision process. For the first time in decades the decision that was made about this recurring, contentious issue coincided with the Tribe’s priorities.

Assessment of CERP Tribal Consultation and Coordination

The USACE and the SFWMD are fortunate to each have skilled, committed Tribal liaisons who facilitate consultation and coordination between their agencies and the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribes. The Tribal liaisons have worked to establish good relationships with Tribal staff and leadership and typically interact with them multiple times each day. They coordinate high-level government-to-government consultations, facilitate Tribal membership on project design teams, and ensure that the Tribes are invited to participate in subteams and attend agency hosted meetings. The agency Tribal liaisons also participate in Tribally led activities (C. Thomas, USACE, personal communication, 2023). The scope of their jobs and the demands on them appear to be excessive for a single individual within each agency. Furthermore, reliance on a single individual as the fulcrum for this critical function represents a risk to the continuity of good consultation and coordination should the individual abruptly be unable to fulfill the role. Progress notwithstanding, some lapses in consultation and coordination continue to occur. Given the volume of work, some measure of this may be inevitable.

However, it is worthwhile to consider and address their causes. Reasons for lapses include understaffing, simple oversight and scheduling conflicts, intensive work schedules, pressure for timely completion of agency work, and in some instances a lack of experience working with Indigenous Knowledge. Nevertheless, some CERP scientific staff consistently engage with the Tribes and consider Indigenous Knowledge in project planning (C. Thomas, USACE, personal communication, 2023), which appears to be increasingly the case. Where there has been resistance, attitudes may be changing, propelled in part by the 2022 guidance from the Executive Office of the President (EOP, 2022a) and as senior scientists learn more about Indigenous Knowledge (e.g., through careful reading of Kimmerer, 2013). The Miccosukee Tribe as well as the Tribal liaisons for the USACE and the SFWMD have stated publicly to the committee that the culture of listening and cooperation is increasing. Progress in scoping and planning for the WERP and recent deviations in operation of the S-12A and S-12B structures reflect the positive trajectory in consultation and coordination.

The Tribes may also face challenges in the consultation and coordination process because of the volume and pace of Everglades restoration work, especially given the much larger USACE and SFWMD staff sizes. It can be difficult for Tribal staff to attend to all the demands of the CERP process. Differences in the timescales on which CERP projects operate and on which Tribes deliberate may also pose challenges, emphasizing the need for early engagement and the understanding that the Tribal process may require multiple levels of Tribal concurrence and approval. In addition, although Tribes are invited to participate in the Task Force Science Coordination Team and Working Group meetings, they have not always believed that there is space for, or interest in, their concerns and knowledge (K. Cunniff, Miccosukee Tribe, personal communication, 2024). However, as relationships between the Tribes and agencies continue to develop through Tribal engagement efforts, the path toward inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge is expected to become smoother and increase in value to decision makers.

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE AND THE SCIENTIFIC PROCESS

Indigenous Knowledge

Broadly speaking, Indigenous Knowledge5 refers to the body of knowledge generated by Indigenous peoples about their environment and appropriate relationships between people and that environment. Understanding Indigenous Knowledge and its interface with western science and land management is fun-

___________________

5 Over the past two to three decades, Indigenous Knowledge has been variously referred to as Indigenous Ecological Knowledge, Indigenous and Local Knowledge, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

damental to honoring the federal trust responsibility and the laws of the State of Florida in Everglades restoration. The Inuit Circumpolar Council6 defines Indigenous Knowledge as

a systematic way of thinking applied to phenomena across biological, physical, cultural, and spiritual systems. It includes insights based on evidence acquired through direct and long-term experiences and extensive and multigenerational observations, lessons and skills. It has developed over millennia and is still developing in a living process, including knowledge acquired today and in the future, and it is passed on from generation to generation.

Just as Indigenous cultures are diverse, so too is Indigenous Knowledge, its forms of expression, and its means of transmission through oral traditions (EOP, 2022a; IPBES, 2022; Robinson et al., 2021). As a result, efforts to understand and include Indigenous Knowledge in Everglades restoration require sustained commitment to understanding the specific knowledge and concerns of each Tribe.

Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science Are Different but Complementary

The fundamental differences between western science and Indigenous ways of knowing have resulted in Indigenous Knowledge being undervalued, marginalized, and often ignored in ecological restoration. Most modern restoration is based on western science, to include hypothesis testing, the scientific method, modern technology, quantitative methods, and a reliance on peer-reviewed scientific publications. In contrast, Indigenous Knowledge is rooted in an intimate holistic understanding of the environment, including the spiritual and ecological relationships between people and their environment, that is often passed down through rich traditions of oral history, rituals, and ceremony. Both pathways of knowledge bring value to ecological restoration, and both have limitations, but western institutions chronically undervalue Indigenous Knowledge because it does not follow the constructs of western knowledge systems (Zedler and Stevens, 2018).

Indigenous Knowledge is often continuously accrued and transmitted over longer timescales, sometimes for centuries to millennia, than knowledge generated from technologies and techniques of western science (Gadgil et al., 1993). It is often based on frequent (e.g., daily) observations and interactions, which is in stark contrast to periodic, seasonal, or short-term observations made in many western scientific studies. Although Indigenous understanding may not always provide the quantitative data that form the foundation of much of western science, Indigenous Knowledge is invaluable for detecting deviations from baseline

___________________

6 See https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/icc-activities/environment-sustainable-development/indigenous-knowledge.

conditions and patterns (or the “normal” range of conditions against which current conditions can be compared) that occur within ecosystems over broad timescales (Riedlinger and Berkes, 2001; also see Box 3-6). Thus, Indigenous Knowledge and western science can provide complementary insights, similar to the way that different disciplines offer unique expertise, methods, and perspectives to solving complex problems.

One shortcoming of western science and monitoring is the lack of long-term, multi-decadal knowledge of most species and ecosystems. Long-term data are especially critical to understanding gradual changes and trends in ecological processes (Hughes et al., 2017; Kuebbing et al., 2018), and are paramount to studying the demography and population dynamics of long-lived species (Clutton-Brock and Sheldon, 2010; Margalida, 2017). In recent decades, anthropogenic pressures on ecosystems have heightened the western scientific community’s collective awareness that long-term research and monitoring are critical for establishing baselines and, therefore, interpretation of changes over time (Kuebbing et al., 2018). Although progress has occurred on several fronts (e.g., National Science Foundation’s Long-Term Ecological Research [LTER] sites and the National Ecological Observatory Network [NEON]7), the western scientific system still struggles to maintain studies longer than typical research funding cycles (~5 yrs) or the focus of individual researchers (approximately two to three decades in most best-case scenarios). Regardless, baselines established through western science generally are recent and developed over much shorter time periods compared to those established through Indigenous Knowledge.

There are examples of Indigenous Knowledge and western science serving as the basis for planning and implementation of successful conservation and restoration projects around the world (Box 3-7). Such collaborations may be especially effective in the development of indicators and monitoring programs (Box 3-6) (IPBES, 2022).

The lack of integration of Indigenous Knowledge in modern ecological restoration projects can manifest itself in several ways. For example, Tribal members are increasingly granted a seat at the decision-making table for restoration projects, but they are seldom placed in a leadership position of these decision-making bodies (Hernandez and Vogt, 2020). Instead, their representation is often a symbolic gesture or in fulfillment of policy requirements or administrative frameworks for best practices. This unintentional “tokenism” ultimately diminishes the importance of Indigenous Knowledge in decision making (Samuel, 2020). Such an approach is particularly problematic because Tribal members represent sovereign nations and are not merely another stakeholder in

___________________

7 See https://lternet.edu and https://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/neon.

BOX 3-6

Case Study on Monitoring, Management, and Restoration of Natural Resources Using Indigenous Knowledge

The Cree Indians of Northern Quebec are well known for their monitoring and management of the natural resources they depend on, including moose, fish, birds, and beavers. Their cultural belief system requires that they harvest responsibly, never taking more than is given to them by the North wind, God, and the animals spirits (Feit, 1986). These cultural views, coupled with their deep multigenerational knowledge of the animals’ biology and the surrounding ecosystem, have enabled the Cree to sustainably manage natural resources for centuries. But the balance they have maintained for generations has repeatedly been disrupted by non-Indigenous people, resulting in overharvest and severe population declines of species in their region. As a result, restoration of animal populations in Northern Quebec has required a combination of Indigenous Knowledge, western science, and government policy to restore the balance.

Beavers are ecosystem engineers that create and change habitats important for maintaining regional biodiversity (Wright et al., 2002) and providing ecosystem services (Thompson et al., 2021). Beavers are also among the more important animals to the Cree people (Berkes, 1998). Beavers require careful monitoring and adaptive management to maintain healthy populations, the habitats that they engineer, and the ecosystem services they provide. To accomplish this goal, the Cree rely on their local knowledge to make decisions about how many beavers can be harvested, when they can be harvested, and in what locations (Feit, 1986).

The Cree’s traditional lands are divided into hunting territories that are each supervised by an individual steward, often a male elder, who maintains intimate knowledge of the status of beavers on his territory based on continuous observations of their activity and population trends, responses of local vegetation to beaver grazing, and personal knowledge of beaver harvests on their territory in prior years (Berkes, 1998; Feit, 1986). Based on the relative trends observed, they then make informed decisions about what portions of their territory, if any, can accommodate harvest. This ongoing assessment sometimes results in stewards not harvesting beavers on some or all of their territory in a particular year or until local recovery is evident, often on multi-year cycles (Berkes, 1998; Berkes et al., 2000), a practice akin to adaptive wildlife management in western science-based systems. This efficacy of Indigenous Knowledge has stood the test of time but also has been challenged by outside influences.

Since the 1700s, beaver populations in Northern Quebec have repeatedly been decimated by overharvest for the lucrative fur trade. For example, in the 1920s, non-Indigenous trappers engaged in unsustainable trapping of beaver on Cree lands, resulting in abrupt crashes in beaver populations, with important consequences for the ecosystem and Cree culture. Faced with a vanishing resource, the Cree management system broke down (Feit, 1986). In response, the Canadian government enacted new laws in the 1930s that created formal recognition and protection of Cree hunting territories, and by the 1950s beaver populations were rebounding under the Cree’s effective management practices (Berkes et al., 1989). Moreover, in 1975, the Canadian government went a step further to enact legislation that gave the Cree full legal authority over beaver management in the region (Moller et al., 2004). In addition to formalizing their legal rights to manage the resource, the agreement also helped forge effective collaborations between the Cree people and western scientists (Moller et al., 2004).

BOX 3-7

Lessons Learned: Indigenous Knowledge and Monitoring Can Provide Insights Where Western Science Falls Short

The sooty shearwater (Ardenna grisea, formerly Puffinis griseus) is one of the most common species of seabirds in the world but has experienced enigmatic population declines over the past 35+ years (Carboneras et al., 2020; Scofield and Christie, 2002; Shaffer et al., 2006). Sooty shearwaters have a broad global distribution, spending most of their life covering great distances at sea to forage and engaging in transequatorial pan-Pacific flights, but they congregate annually in exceptionally large numbers along the coast of New Zealand to breed (Carboneras et al., 2020; Shaffer et al., 2006). The Raikura Māori, Indigenous people from southern New Zealand, are permitted to harvest chicks each year in large numbers (250,000–300,000; Carboneras et al., 2020) from the surrounding Tītī islands for food, soap, oil, and trade. This practice, called muttonbirding, is an important part of the Māori’s cultural identity as well as their economic well-being (Moller et al., 2004). For generations, the Māori have closely monitored their harvest in relation to their hunting effort and the body condition of the chicks harvested, and they often record their observations in multi-decadal diaries (Lyver, 2002; Lyver et al., 1999). Their observations are robust enough to document fluctuations in shearwater populations that are predictive of El Niño-Southern Oscillation patterns, as corroborated by western statistical models (Humphries and Moller, 2017; Lyver et al., 1999).

Importantly, the Māori’s observations also served as early evidence of long-term population declines. The Māori observed declining yields of shearwater chicks per harvest effort, with no changes to chick body condition or nesting habitat quality, leading them to conclude that shearwater populations were gradually declining and that declines were caused by factors not associated with the breeding habitat or their annual harvest. The testable hypotheses generated from the Māori led to intensive studies by western scientists to identify the mechanisms driving the population declines of shearwaters (Moller et al., 2004). Today, it is generally agreed that fisheries bycatch in nets on the open ocean, and the effects of climate change, possibly on food resources, are the primary causes of their population declines in New Zealand as well as in other portions of the world (Brooke, 2004; Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, 2023; Scofield, 2000; Uhlmann and Jeschke, 2011; Veit et al., 1997). Thus, the long-term knowledge of the Māori proved invaluable for detecting deviations from historical conditions as well as identifying distant factors as the most probable causes of the population declines, and it alerted western scientists to deploy technological tools and modeling to identify the underlying mechanisms (Moller et al., 2004). Both ways of knowing proved mutually beneficial for identifying and solving this conservation mystery, which could ultimately lead to management interventions (e.g., altering fishing practices).

these decision-making groups (Robinson et al., 2021). Token representation in meetings and on decision-making bodies perpetuates false western notions that Indigenous Knowledge has secondary value to western science and degrades trust between Tribal members and western practitioners.

Moreover, failure of western practitioners to effectively consider Indigenous Knowledge in ecological restoration and monitoring undermines the

BOX 3-8

Klamath Tribes and Watershed Restoration

The Klamath River Basin is an example of where multiple Tribes have worked collectively with western science practitioners to restore land, water, and ecological resources. At the watershed level, the Karuk Tribe has focused on using traditional Indigenous Knowledge based in its cultural relationship with the Klamath watershed to establish restoration goals to enhance the social and ecological resilience to natural and anthropogenic disturbances and climate change stressors. Through a mix of methods grounded in both Indigenous and western science methods, the Karuk Tribe developed metrics for assessment centered on land use and land cover change detection and interviewed Tribal community elders and keepers of knowledge to collect information on land use history and changes over time.a This approach has been credited with contributing significantly to ecocultural-based restoration planning strategy.

__________________

a See https://nature.berkeley.edu/karuk-collaborative.

SOURCE: Eitzel et al., 2024.

rigor of their efforts and broad utility of restoration outcomes by relying on a narrow suite of perspectives and toolsets. For example, modern paradigms related to coupled socioecological systems require a clear understanding of the complex, nonlinear, and deeply interdependent relationships between human societies and the environments within which they operate and are part of (Berkes, 2017). Thus, modern ecological restoration is maximally effective when it considers similar complex relationships in pursuit of integrated ecological, social, and cultural indicators of restoration success (e.g., biocultural or ecocultural restoration; Lyver et al., 2016) (Box 3-8). Likewise, monitoring the efficacy of ecological restoration projects can be improved with the inclusion of Indigenous monitoring criteria, which often account for indicators of success that differ from those prioritized by western science (Thompson et al., 2019, 2020). Indigenous cultures generally have a richer understanding of the place and context of human communities in nature than western societies do (e.g., kincentric ecology; Salmón, 2000). Because modern restoration projects are typically societal problems, they cannot be fully resolved with technical tools and thus require a deep understanding of the bi-directional nature of the relationship between humans and their environment (Lyver et al., 2016). As a result, restoration efforts have a lot to gain by incorporating the deep understanding of socioecological systems afforded by Indigenous Knowledge, just as most modern problems benefit from the integration of multiple disciplines, perspectives, and approaches.

Challenges

There is concern among staff in some agencies about the compatibility of Indigenous Knowledge with NEPA requirements. At least two types of concern are present: (1) satisfying requirements for academic rigor, as defined by the western scientific community, for federal decision making under the Information Quality Act (2000) (Section 515 of Public Law 106-554; 67 FR 8452) and (2) safeguarding Indigenous data sovereignty and governance while meeting the federal transparency requirements. Understanding and resolving these issues is paramount to including Indigenous Knowledge in any endeavor and requires true partnership with trust.

Satisfying Agency Requirements for Western Scientific Rigor

Complicating efforts to include Indigenous Knowledge in federal decision making is a perception that such knowledge, by its very nature, falls short of satisfying western scientific scrutiny and thus federal information quality standards. For example, the Office of Management and Budget Guidelines for Ensuring and Maximizing the Quality, Objectivity, Utility, and Integrity of Information Disseminated by Federal Agencies (67 FR 8452) present a requirement of “objectivity” that presumes favoring peer-reviewed western academic science and research. These guidelines, in conjunction with the Information Quality Act of 2000 (Section 515 of Public Law 106-554), stipulate that “influential information . . . is required to provide sufficient transparency about data and methods to allow reproducibility of the results,” constraining the type of Indigenous Knowledge that can be applied in federal decision making and potentially compromising Indigenous data sovereignty and governance. A significant obstacle to inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in agency decision making is the enforcement of a “highly bureaucratic process of translating traditional knowledge into a format that fits federal requirements for information quality and evidence management” (Ornstein, 2024). Much of the guidance on data quality implies that knowledge-bearers possess the acumen to navigate voluminous government procedure and package Indigenous Knowledge to satisfy the constraints of western evidence, potentially altering the nature and interpretation of the information. However, as discussed in the previous section, Indigenous Knowledge can provide a deep understanding of socioecological systems necessary for successful restoration efforts (Ban et al., 2018; Jessen et al., 2021). Agencies will need to work with Tribes to gain a better understanding of the rigor underpinning Indigenous Knowledge using the recommendations for meaningful engagement highlighted in this chapter.

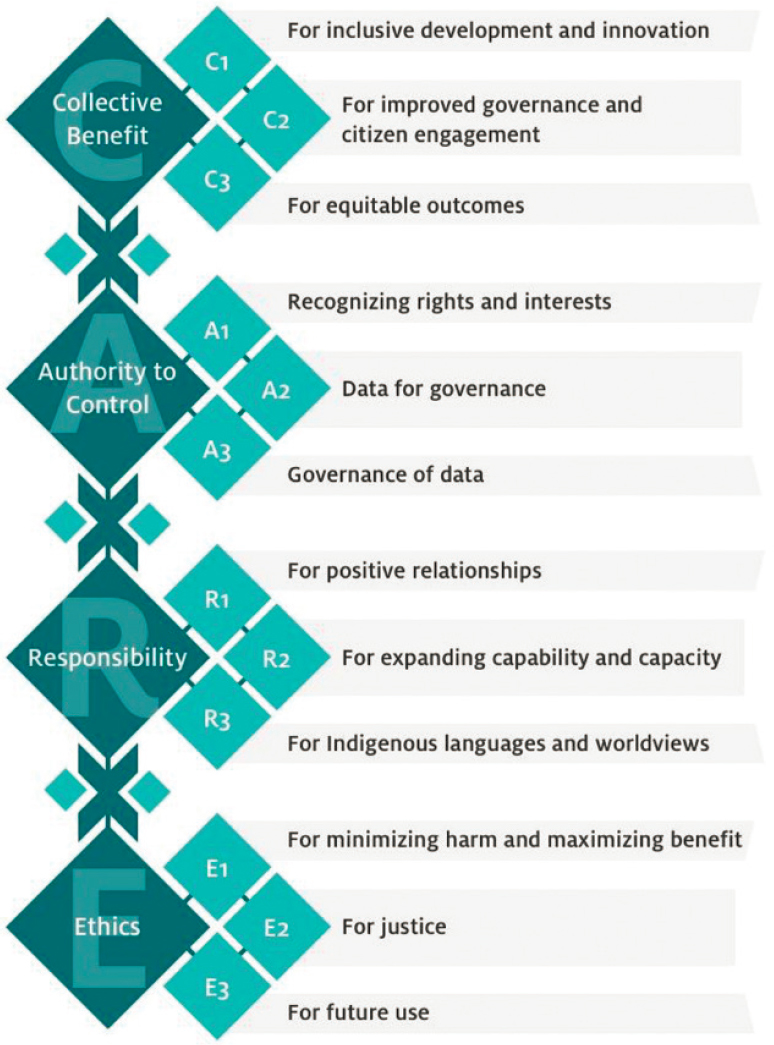

Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance

Indigenous data sovereignty is “the right of Indigenous peoples to exercise ownership and protection over Indigenous data. Ownership of data can be expressed through the creation, collection, access, analysis, interpretation, management, dissemination and reuse of Indigenous Data” (Williamson et al., 2023). Indigenous data governance is “the stewardship and the processes necessary to implement Indigenous control over Indigenous data” (Carroll et al., 2020). Indigenous data sovereignty and governance are founded on the inherent sovereignty of Indigenous peoples affirmed in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Article 31.1; United Nations, 2007):

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.

Indigenous data sovereignty and governance are therefore part and parcel of Indigenous self-determination and autonomy.

In the face of climate change and environmental degradation, ecological and climate research studies increasingly include Indigenous Knowledge, often without meaningful participation or decision-making authority from the communities who are stewards of this knowledge, despite the purported value placed on Indigenous Knowledge by western scientists (David-Chavez and Gavin, 2018; Jessen et al., 2021; Williamson et al., 2023). Of particular concern to Indigenous communities is the misrepresentation and misuse of Indigenous Knowledge outside of its full cultural context in a western information ecosystem that perpetuates power imbalance (Kukutai and Taylor, 2016). For instance, Indigenous Knowledge of the medicinal properties of plants in remote biodiverse regions has been appropriated for commercial pharmaceutical breakthroughs that harm local Indigenous communities because of patenting and restricting the use of plants and animals to those same communities, a practice known as “biopiracy” (Cottrell, 2022; Shiva, 2016). The long and harmful history of appropriation and misuse of Indigenous Knowledge by westerners has led to recognition of “the right of Indigenous peoples to autonomously decide what, how and why Indigenous data are collected, accessed and used to ensure that data on or about Indigenous peoples reflects their priorities, values, cultures, worldviews and diversity” (Williamson et al., 2023).

Without recognition of Indigenous data sovereignty and multi-lateral data-sharing agreements on the terms under which it can be used, Everglades restoration cannot fully benefit from the wealth of knowledge that Tribes have accumulated over generations—knowledge that can provide important alternative perspectives and ultimately inform a richer suite of management options and outcomes. These two obstacles to applying Indigenous Knowledge to support Everglades restoration—western perceptions and requirements applied to the quality of Indigenous data and Indigenous data sovereignty—are not insurmountable; examples of and principles for overcoming these obstacles abound in the literature and in practice. In the sections below the committee highlights best practices, case studies, and recommendations for partnering with the Tribes to include Indigenous Knowledge in decision making for Everglades restoration.

BEST PRACTICES FOR INTEGRATION OF INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE IN FLORIDA EVERGLADES RESTORATION

Building Trust Through Meaningful Engagement

Different levels of consultation are presently practiced as part of the CERP, including informal discussions, formal information meetings, and formal agency-to-agency consultation. Effective consultation and meaningful engagement depend on the establishment of trust and good relationships between organizations and the individuals within those organizations. Frequent, open, and consistent communication between key agency leaders and staff and Tribal leaders and staff is key to establishing and maintaining good relationships. Building trust occurs across a range of activities from the ground up rather than as top-down reactions to contentious decisions or disputes, where much of government engagement with Tribes has historically occurred.

Principles of meaningful engagement should govern all interactions with the Tribes. Box 3-9 summarizes current guidance on meaningful engagement. These best practices should ideally be initiated before the start of any project with an understanding that gathering and conveying Indigenous Knowledge does not operate on the same timetable as planning requirements (e.g., see Box 3-10). However, strengthening relationships and partnerships should be viewed as a continual and ongoing process. Although Everglades restoration has been in the planning stages and under way for decades, opportunities still abound for forging strong reciprocal partnerships with the Tribes. Indeed, there is an imperative to do so.

Ultimately, the inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in planning and restoration requires genuine partnerships based on trust, joint goals, and mutual respect.

BOX 3-9

Recommended Practices for Meaningful Engagement

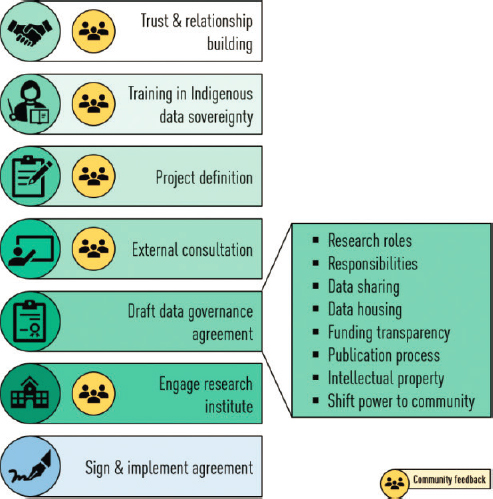

Meaningful engagement is established through building strong, trusting, and reciprocal relationships. The groundwork to foster meaningful engagement takes time but ultimately strengthens relationships and outcomes over the long term. Several non-exhaustive best practices for establishing meaningful engagement are outlined below. They have been adapted primarily from Shelter, Support and Housing Administration (2019) and supplemented with recommendations from other sources (CTKW, 2014; Lukawiecki et al., 2021; Reo et al., 2017).

- Understand the historical and current colonial context of the region and people with whom you are engaging. Understand how this context impacts Indigenous communities and your own power and privilege as it relates to Indigenous peoples. Take cultural competency/safety training and spend time reading about the history and culture of Indigenous peoples in the region.

- Recognize Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination and autonomy. Engagement with Indigenous peoples should be viewed as a nation-to-nation interaction rather than stakeholder outreach.

- Engagement must be mutually beneficial. Benefits must relate not only to the project’s mission, values, and priorities but also to those of the Indigenous communities impacted. Ensuring the needs of the community, and not solely the needs of the project, should be the foundation of good engagement.

- “Nothing about us without us.” Indigenous partners have emphasized the importance of policy, planning, and program development being Indigenous-led or co-created in recognition of Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination and autonomy. This approach will ensure that the work is grounded in an Indigenous perspective, follows appropriate protocols, and better addresses the needs and priorities of Indigenous communities.

- Good engagement is a process that focuses on relationship building. Engagement is an ongoing, reciprocal, and cyclical process. Consider how you will know whether you have done good consultation work and how you will obtain this feedback. How will it be determined that effective engagement has been achieved and the opinions of Indigenous communities have been heard and understood?

- Engagement should begin early in the project and continue throughout all stages of the project (project initiation, planning, implementation, reporting back to communities, and evaluation). In some cases, multiple meetings will be necessary to ensure the community has been thoroughly informed as to the outcomes of the consultation.

- Whenever possible, meet Tribes in the location of their choosing. Endeavor to understand and respect Tribal protocols and be attentive to opening ceremonies. In Tribal territory, know that meetings commonly begin with prayers and/or ceremonies, often conducted in the Tribe’s native language. These rituals set the tone and aspiration for the event and much can be learned from them. Take them in with respect and endeavor to maintain that tone throughout the engagement.

- Engagement is not outcome-based and will not necessarily result in Indigenous peoples agreeing with or supporting the intentions or goals of the project. Using appropriate engagement is a relational practice and not intended to sway the opinions of communities.

- Take time to learn and understand the concerns of the community. Often the community will raise concerns that will strengthen the project and the well-being of the community. Do not assume that if a certain approach or form of engagement worked with one group/community that it will work with another. Although it is helpful to draw on previous engagements, there is no “one size fits all” approach. Seek the community’s advice on appropriate engagement.

- Develop reciprocal processes for knowledge sharing that respect Indigenous Knowledge and data sovereignty and governance. Create opportunities for co-production of knowledge and co-authorship on publications.

- Build capacity for Indigenous communities to participate in the project and find ways to support Indigenous-led initiatives to govern and manage aspects of the project that are important to them.

BOX 3-10

Tribal Engagement in the Klamath Dam Removal Project

The Klamath River Hydroelectric Project has blocked fish passage and altered the Klamath River flows for more than 100 years. The Klamath River watershed is the traditional homelands of the Klamath Tribes, Yurok Tribe, Karuk Tribe, and Shasta Indian Nation. The Klamath River has been diverted, dammed, and impacted by changed water quality and blockage of access for salmon due to upstream agricultural, logging, and development pressures. To the Tribes, the Klamath River and the salmon that it supports are central to their culture. Socially and culturally the river itself represents the essence of life and is essential to the health and social well-being of the Indigenous people and the watershed.

After years of discussion, debate, and failed legislative attempts at resolution of Tribal and conservation concerns, an agreement was reached with the dam owners to remove four Klamath River dams. In the early 2020s consultation with the Tribes was initiated, and baseline scientific data and cultural resource work was initiated. In 2023 work on the removal of the four dams was initiated. The Tribes have been invested in the dam removal and river restoration process from the beginning. The company hired to design, implement, and oversee the restoration process consulted with the Tribes to integrate Indigenous Knowledge. The Yurok Tribe and the Shasta Indian Nation have been active participants in the restoration and revitalization of the Klamath River canyon, the watershed, and the salmon runs that historically populated the river.

Indigenous Knowledge has been applied in conjunction with western science, resulting in a dynamic approach to river restoration. Examples of how Tribal knowledge has been applied in the Klamath restoration effort include the following:

- Early and continuous conversations with the Tribes ensured their history with the river was understood and considered in the restoration planning.

- For 5 years prior to the first dam removal, the Klamath River Tribes have been gathering native seeds by hand and sending them to nurseries for storage until conditions are favorable in the exposed reservoir sediments along the restored river corridor for replanting.

- The Tribes identified areas where temporary habitat can be placed in the new river channel to aid migrating salmon and trout.