Forecasting the Ocean: The 2025–2035 Decade of Ocean Science (2025)

Chapter: 2 Urgent Ocean Science Research Portfolio

2

Urgent Ocean Science Research Portfolio

In his report that led to the creation of the National Science Foundation (NSF), Vannevar Bush (1945) argued for the importance of basic research, citing the “flow of new scientific knowledge” and the understanding that this “new knowledge can be obtained only through basic scientific research” (pp. 1, 7). Bush argued strongly for U.S. leadership in the pursuit of science; regaining such leadership is still important today, not only for national security but also for the United States’s ability to attract and convene the best scientific minds, generating a workforce with skills that will fuel a thriving economy.

Confirming Bush’s vision, basic research in the field of ocean sciences has resulted in advances in predictive technologies that have led to benefits for humans, including reductions in loss of life. As one example, basic ocean research on air–sea interaction and surface wave dynamics has dramatically improved path and intensity forecasts for hurricanes and their resulting storm surges, thereby saving lives and reducing economic loss (Cangialosi et al., 2020; Miles et al., 2021). The ability to predict or forecast other ocean processes is essential for adapting to change and mitigating loss (Link et al., 2023). For example, basic research has revealed that ocean species can impact the physical and chemical nature of the ocean, including aiding in carbon sequestration, absorption of heat in the surface ocean, influencing the flow of nutrients, and even impacting wave energy. Understanding how ocean life populations adapt to environmental change is essential for forecasting ecosystem resilience.

This chapter emphasizes the importance of and need for basic research and shares urgent ocean research priorities, organized in three overarching themes and framed under a single challenge for the next decade.

BASIC RESEARCH IS KEY

The program officers at the Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE), as those in other divisions of NSF, act as fair brokers to evaluate ocean science research proposals; after conferring with external peer reviewers and a panel or committee of experts, program officers decide which proposals to fund. The goal of the process is to fund those proposals that best stand to advance understanding of the ocean and its role in the Earth system and that have impacts on education and other societal benefits in addition to the proposed research objectives. Funded proposals are often in the category of basic research that lacks immediate known applications, although use-inspired proposals are also encouraged. And in some cases, NSF research announcements solicit proposals that encourage research related to a specific societal benefit. However, it is the support of unsolicited proposals for basic ocean science research that distinguishes OCE from other federal mission agencies in the ocean sciences. This basic research underpins the eventual applied societal benefits.

Over the course of this study, the committee evaluated testimony from the scientific community on the future basic research needed across the field of ocean sciences, including applied and multidisciplinary topics, such as effects on ecosystems, marine geoengineering strategies, potential benefits and hazards associated with a new economy for marine critical minerals and carbon sequestration, precursors to subduction zone geohazards, changes in biodiversity and biogeography patterns for marine organisms, and the multistressed urban seas and coastal ocean (see Appendixes B and C).

CONCLUSION 2.1: NSF is the only U.S. federal funding agency intentionally founded with the explicit mission to sponsor basic research. Such supported research produces the raw intellectual knowledge that will yield tomorrow’s solutions. To support national security, a skilled U.S. workforce, and a thriving economy, continued, dedicated NSF funding is critical for principal investigator–driven

research projects that address questions fundamental to understanding the ocean and its interactions with other parts of the Earth system.

RECOMMENDATION 2.1: The National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences should continue to support a broad portfolio of basic research to ensure that scientists and engineers of the future have access to a continually improved understanding of the ocean to advance and fuel innovation and resilience in the United States.

A CHALLENGE FOR THE NEXT DECADE

Based on the prioritization work described in Chapter 1, the committee developed an overarching challenge for the next decade of ocean sciences: forecasting the state of the ocean at scales relevant to human well-being (Box 2.1).

BOX 2.1

The Challenge

By 2035, establish a new paradigm for forecasting ocean processes at scales relevant to human well-being, emphasizing three interconnected themes: ocean and climate, ecosystem resilience, and extreme events. Establishing this paradigm will require a relentless focus on furthering basic science to observe and understand ocean processes through the lens of innovative disciplinary, as well as transdisciplinary, research practices.

The committee elevates the ability to forecast as its challenge to emphasize the importance of developing testable hypotheses of future conditions. Figure 2.1 illustrates the steps leading to a forecast, as well as the feedbacks from initial forecasts that provide priorities for improving measurements and for better understanding of the process(es) under study. While forecasting is elevated here, all steps in the continuum are essential. Better understanding will in turn improve new forecasts. Forecasts are also key to addressing use-inspired issues beyond basic research and for identifying and prioritizing efforts that are needed to respond to changes in the Earth system that affect human well-being.

Translating basic research into forecasts that are operational requires partnerships with other mission agencies focused on ocean sciences. For some challenges (such as some extreme events), society might best be served with forecasting timescales of days to weeks; others (such as sea level rise) may require longer timescales. Similarly, decisions on fishery management, ecosystem services, or renewable energy considerations potentially contain multiple decision time- and space scales, so no single forecasting system can be constructed that can be helpful in all cases. In other words, forecasting the state of the ocean at scales relevant to human life must occur at various temporal and spatial scales as dictated by the societal questions at hand and by the nature (e.g., rates of change, response times) of the ocean system processes.

Research is also needed on the limits of the predictability of the ocean system. These limitations may be due to the lack of detailed knowledge of the state of the system or to inherent complexities in the system that may lead to chaotic behavior. Thus, some ocean processes may be difficult, if not impossible, to predict with any accuracy (NASEM, 2020). These complexities may necessitate the development of probabilistic approaches to eventually serve as components of forecasting systems.

The ultimate goal of forecasts is to contribute to federal management and policy decisions by government and private entities that promote resiliency and prosperity, and position the United States as a leader in transformative ocean science. OCE-sponsored basic research, including transdisciplinary research, is necessary to achieve this goal of operational forecasting for as many processes as possible.1

2025–2035 OCEAN RESEARCH PORTFOLIO

Basic research across all disciplines of ocean sciences is sorely needed, and an argument can be made for elevating the importance of almost any topic. Yet the committee’s task (Box 1.2) was to develop a “concise portfolio of compelling, high-priority, scientific questions that have the potential to transform scientific knowledge of the ocean and the critical role of the ocean in the Earth system.” Based on criteria included in Box 1.3, and in pursuit of the challenge (Box 2.1), the committee prioritized the following urgent, high-priority science themes and questions for the next decade—ocean and climate, ecosystem resilience, and extreme events (Figure 2.2).

___________________

1 Transdisciplinary research is defined in Box 1.1 in Chapter 1 and further discussed in Chapter 3.

This compelling, cross-cutting research portfolio should galvanize the ocean science community to work together towards the challenge, and common goal, of establishing a new paradigm for forecasting ocean processes at scales relevant to human well-being by 2035.

CONCLUSION 2.2: In addition to continued NSF funding for wide-ranging basic ocean science research, three themes and research questions urgently need to be addressed through the application of improved forecasting capabilities in the next decade and beyond:

- Ocean and climate—How will the ocean’s ability to absorb heat and carbon change?

- Ecosystem resilience—How will marine ecosystems respond to changes in the Earth system?

- Extreme events—How can the ability to forecast extreme events driven by ocean and seafloor processes be improved?

RECOMMENDATION 2.2: The National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences should support basic research that addresses the goal of forecasting ocean processes at scales relevant to human well-being, with emphasis on the following themes and questions:

- Ocean and Climate—How will the ocean’s ability to absorb heat and carbon change?

- Ecosystem Resilience—How will marine ecosystems respond to changes in the Earth system?

- Extreme Events—How can the ability to forecast extreme events driven by ocean and seafloor processes be improved?

Each of these themes and questions are explained further in the sections that follow. In many respects, they amplify the priorities highlighted in past reports (e.g., NASEM, 2017a, 2022a, 2022b, 2024b, 2024c; NRC, 2015), and thus they contain lines of inquiry that are familiar and well supported. Here, however, they are combined in ways that emphasize the connections between elements of ocean processes and ocean life that are fundamental to accurate dynamic forecasting.

The priority research themes are both goal oriented and purposefully general, providing space for researchers to connect their research to the theme while still advancing towards a common goal. Table 2.1 provides an overview of the types of research questions that could be included within each theme, as well as the potential societal uses and outcomes of the research and common resources needed to advance all three themes, with context following in the remainder of the chapter. Each of the next three subsections begins with the importance and urgency of each theme and continues with background and context. The societal relevance and broader impacts of the research are also highlighted, followed by a high-level discussion on the resources required for successful conduct of such research.

TABLE 2.1 Urgent Priorities for Ocean Sciences Research, 2025–2035

| OCEAN AND CLIMATE | |

| Urgent Question | How will the ocean’s ability to absorb heat and carbon change? |

| Example Research Directions |

|

| OCEAN AND CLIMATE | |

| Example Use-Inspired Cases |

|

| Potential Outcomes |

|

| ECOSYSTEM RESILIENCE | |

| Urgent Question | How will marine ecosystems respond to the changing Earth system? |

| Example Research Directions |

|

| Example Use-Inspired Cases |

|

| Potential Outcomes |

|

| EXTREME EVENTS | |

| Urgent Question | How can the ability to forecast extreme events driven by ocean and seafloor processes be improved? |

| Example Research Directions |

|

|

|

| Example Use-Inspired Cases |

|

| Potential Outcomes |

|

| CLIMATE AND OCEAN; ECOSYSTEM RESILIENCE; EXTREME EVENTS | |

| Resources Needed |

|

OCEAN AND CLIMATE

How will the ocean’s ability to absorb heat and carbon change?

The ocean is presently absorbing 90 percent of the heat (von Schuckmann et al., 2023) and roughly 30 percent of the carbon that result from global emissions of greenhouse gases (Gruber et al., 2023). Any decline in these rates of uptake would accelerate increases in CO2 levels and temperature in the atmosphere. In essence, the ocean has been operating to slow the impacts of climate change felt on Earth since the industrial revolution. It is unlikely, however, that the ocean will continue this same rate of absorption (Wilson et al., 2022), and it is likely that the patterns of ocean current circulation will shift; these patterns are crucial for carbon and heat distribution (Gray, 2024; Gruber et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2022). Scientists do not

know whether the expected changes will be gradual or if there is a threshold where such shifts will reach a tipping point, where the shift becomes sudden, dramatic, and potentially irreversible. Shifts in how the ocean absorbs heat and carbon can have differing and far-reaching impacts on global ocean circulation and atmospheric processes that include hurricane and storm development and movement; ice sheet stability; ocean chemistry, including acidification, nutrient speciation, and cycling; and ocean productivity and ecosystem health, including major die-off events (e.g., coral bleaching). Research has uncovered the ways in which the Earth system is coupled with the ocean and other systems, yet there is limited understanding about how the coupled relationships will change in the future. The pace of change in our climate, in particular, linked to heat and carbon stored in the ocean, creates an urgency to understand the changes Earth might experience in the coming decades.

Background and Context

Through its capacity to store and transport carbon and heat, the ocean plays a key role in regulating the climate and the carbon cycle (Box 2.2). Observations and models reveal that the ocean has played a critical role in regulating current and past changes in climate and atmospheric carbon concentrations (e.g., glacial–interglacial cycles). For example, studies of cored subseafloor sediments recovered by scientific ocean drilling have demonstrated a connection between AMOC, regional climate change, and carbon uptake by the ocean. This relationship indicates that changes to the strength of AMOC could be a key component of the ocean’s response to future warming, including altering ocean circulation patterns, which would impact global heat transport, potentially affecting regional climates, global atmospheric circulation, and the hydroclimate in general (e.g., Ait Brahim et al., 2022; Sallée et al., 2023; Walczak et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021).

Long-term, sustained observations supported by OCE in partnership with other directorates and agencies have provided some of the most critical insights into how the ocean’s physical and chemical properties have changed over the last several decades. This includes long-term time-series sites, such as Station ALOHA (sampled by the Hawaii Ocean Time-series) and the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study; long-term regional programs, such as the California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations survey, coastal and ocean Long-Term Ecological Research sites, the global Argo float program; and the Global Ocean Ship-based Hydrographic Investigations Program (GO-SHIP), which has resampled ocean transects that were established in the 1990s. GO-SHIP has provided crucial ship-based measurements on global ocean carbon and related parameters, unavailable to any other observation platform, and has enabled an accounting of the ocean anthropogenic CO2 sink. Higher-frequency regional and seasonal observations by biogeochemical (BGC)-Argo have been needed to complement shipboard measurements, which in turn provide calibration data for Argo, to study the Southern Ocean’s role in CO2 uptake (Bushinsky et al., 2019).

Understanding the Ocean Carbon Sink

Researchers are just beginning to understand the role of the Southern Ocean in CO2 uptake (Gruber et al., 2019; Terhaar et al., 2021), as austral winter measurements become more prevalent (Bushinsky et al., 2019). These observations point to the importance of local, seasonal (both winter and summer), and sub-seasonal episodic events (e.g., storms)—which are much more effectively captured by floats and other sustained measurements—for accurately estimating CO2 uptake in the Southern Ocean (Carranza et al., 2024; Hauck et al., 2023). Recent studies have also demonstrated the importance of considering vertical mixing alongside subpolar gyre circulation and the entrainment of carbon in the horizontal circulation, zonal asymmetric in Antarctic circumpolar current, as well and air–sea exchange (Gray, 2024), for CO2 uptake. This contrasts with previous studies that have suggested a central role for meridional overturning circulation in controlling the air–sea CO2 flux and CO2 inventory in the ocean’s interior (MacGilchrist et al., 2019).

BOX 2.2

The Ocean Carbon Cycle

The carbon content of the ocean increases from the surface to the deep sea. The ocean is stratified with different water masses layered horizontally: a relatively thin, low-density, warm layer overlays layers of thicker, denser, colder, and deeper waters. This layered structure limits exchange of carbon between the near-surface waters and the deep layer that holds most of the carbon. Exchange of carbon between these layers occurs through both physical and biological exchanges (Figure 2.3). The physical exchange delivering carbon to the deep ocean occurs mainly in the polar and subpolar regions. Traditionally, the biological exchange has been characterized as dead marine life sinking from the surface to deeper waters, where much of the carbon is respired as this organic matter decays. This is often referred to as the export flux or the biological carbon pump (BCP). Although the traditional view of the BCP implicates gravitational settling, new observations have determined that a number of other pathways—such as subduction zone disturbance, mixing by wind and currents, and zooplankton migration up and down the water column—may be as important as the gravitational BCP in exporting carbon from the upper ocean in certain regions (Boyd et al., 2019; Nowicki et al., 2022; Omand et al., 2015; Stukel et al., 2017). Predicting how the relative importance of the different pathways will change in the future is challenging, especially as marine ecosystems, and thus human communities, change. Without the BCP, atmospheric carbon concentrations would be roughly 200 parts per million (ppm), or about 50 percent higher (Henson et al., 2022). The respired carbon that accumulates in the deep ocean is eventually returned to the surface after hundreds of years through physical mixing.

Given the mass of the ocean carbon reservoir, the ocean will play a key role in moderating carbon levels in the atmosphere. Over the last century, more than 30 percent of the carbon emitted to the atmosphere has been absorbed by the ocean (Gruber et al., 2019). In the future, as the ocean surface continues to warm, the rate at which the surface absorbs carbon from the atmosphere may slow, in large part due to the increasing temperature difference between the surface and deeper layers of the ocean. The temperature gradient, especially in the open ocean, reduces mixing of carbon with the deep ocean and limits nutrient delivery to the surface, which weakens the BCP but also decreases the return of carbon from depth, thus increasing deep carbon storage.

Much remains to be learned about the magnitude and sign of the expected changes in both mixing and biology, and where in the ocean these changes will be most significant and why. More and better measurements are needed to answer these questions, including seasonally resolved observations, and more accurate and complex models, including improved representation of deep-ocean and seafloor processes, as well as machine learning approaches to fill in gaps where data are missing or sparse.

SOURCE: Galen McKinley, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, and Natalie Renier, Woods Hole Oceanic Institution Creative Studio.

Overall, the Southern Ocean has an outsized impact on the atmospheric CO2 inventory because it is where the ocean’s largest CO2 reservoir comes into direct and rapid contact with the atmosphere (Gray, 2024). The importance of this region on ocean CO2 uptake is uncertain (Chikamoto and DeNezio, 2021; Gallego et al., 2020; Zhong and Rojanasakul, 2024); sustained observations in this region will be key to predicting the sensitivity of the ocean carbon sink.

The latest experiments with coupled ocean–atmosphere models indicate that the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon will likely decline, but the magnitude of this decline varies between models (Gruber et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2022). Model uncertainty reflects the fact that the climate system and the carbon cycle are coupled by interconnected processes, making the task of developing accurate forecasts challenging. For example, at the most basic level, as ocean temperature and acidification increase, the capacity of seawater to store carbon decreases. While relatively small positive feedbacks are easy to represent in the models, more substantial changes, which are expected in the next decades, are much harder to represent. Specifically, as the surface ocean warms, thermal stratification slows vertical mixing, both annually and seasonally, particularly at high latitudes. This has multiple impacts, one of which is to weaken the ocean’s biological carbon pump and thus the large-scale transfer of carbon in sinking particles from the surface ocean to the deep sea (see Box 2.2; Wilson et al., 2022). Changes in the biological pump and ocean mixing could also exacerbate the release of carbon into the atmosphere at some locations (Gruber et al., 2023), and the ongoing acidification of the ocean (Carter et al., 2017; Gregor and Gruber, 2021) will reduce the ocean’s chemical ability to absorb carbon from the atmosphere (Figure 2.4). Addressing these and other factors will be critical for reducing the uncertainty in forecasting trends in atmospheric CO2 under various emission scenarios, as well as for identifying potential tipping points where the rate of ocean carbon uptake changes dramatically.

Understanding the Ocean Heat Sink

The representation of ocean heat uptake and distribution in coupled ocean–atmosphere models is still a work in progress. Globally, GO-SHIP repeated ship measurements (occupying stations every 5–10 years), and the core Argo array have provided the most definitive data on the ocean’s uptake of excess warming (von Schuckmann et al., 2023), in part because these measurements provide an unprecedented look at what is happening in the ocean’s interior (Figure 2.5) in space and in time. The core Argo array provides the highest frequency of observations but is primarily restricted to the upper 2000 meters. Because the oceanographic community has recognized the importance of sustained observations over the full ocean depths, Deep Argo2 was developed by Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Teledyne-Webb Research. Such measurements may be important for reconciling the discrepancy between ocean heat uptake measured by in situ methods and those estimated from satellite observations of ocean thermal expansion (Marti et al., 2024).

Based on spatially detailed observations of ocean heat content as measured by Argo autonomous floats beginning in 2005, a picture is emerging of how the accumulated heat is being distributed across each basin from the surface to intermediate depths (700–2000 m; Figure 2.5; Li et al., 2023; von Schuckmann et al., 2023). Such detailed observational constraints have been critical for testing and improving dynamical models and thus identifying the need for improved representation of key physical processes that regulate heat fluxes on various scales.

Research Advancements Needed to Understand the Ocean’s Ability to Absorb Heat and Carbon

Role of Global Circulation

At the largest scale, freshwater and heat are transported by large-scale ocean circulation (e.g., AMOC). However, some models suggest that a slowdown in AMOC will decrease the efficiency of this heat transport

___________________

2 See https://argo.ucsd.edu/expansion/deep-argo-mission/ (accessed January 22, 2025).

(Curtis and Fedorov, 2024; Mecking and Drijfhout, 2023; van Westen et al., 2024). Based on model predictions, the most recent (sixth) annual report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2023) indicates there is a high likelihood that AMOC will decline sometime in the 21st century. The report also states that “there is medium confidence that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation will not collapse abruptly before 2100” (IPCC, 2023, p. 18). However, questions remain as to how much confidence to place in the models’ forecasting abilities, given their relatively poor ability to simulate past AMOC activity and the lack of observational evidence of AMOC decline (McCarthy and Caesar, 2023). Observations of the past recently collected from sediment cores have shown that the sea ice extent in the Southern Ocean can drive high-amplitude, millennial-scale variations in the strength of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which can also influence AMOC by modulating the Pacific–Atlantic exchange of ocean water (Wu et al., 2021). These studies have demonstrated the importance of understanding change at both poles and in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in order to better forecast the tipping point where AMOC reaches a new stable state, perhaps at a decreased strength from what is observed today.

NOTES: DIC = dissolved inorganic carbon; MLO = Mauna Loa Observatory; pCO2 = partial pressure of carbon dioxide; TA = total alkalinity.

SOURCE: Angelicque White. Data: Measurements by the Scripps CO2 Program and the Schmidt Ocean Institute are supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF); by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fund for Strategic Innovation; and by Earth Networks, a technology company collaborating with Scripps to expand the global greenhouse gas monitoring network. In-kind support for field operations is also provided by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, NSF, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and the New Zealand National Institute for Water and Atmospheric Research.

NOTES: Ocean heat content over time relative to the 2016–2020 mean. The red lines in both panels represent the ensemble mean time series of global ocean heat content (OHC), 1955–2020. SIO RG Argo = Scripps Institution of Oceanography Roemmich-Gilson Argo Climatology; WOCE = World Ocean Circulation Experiment.

SOURCE: Li et al., 2023.

Ice Sheet–Ocean Interactions

Understanding the stability of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets is crucial for predicting future sea level rise and deep-ocean circulation. For the Southern Ocean in particular, input of meltwater can alter local circulation, which in turn can impact the role of the Southern Ocean in heat and carbon exchange with the atmosphere. For example, glacial meltwater input can increase stratification and prevent the release of heat from the Southern Ocean interior, which warms subsurface waters further. Warming subsurface waters can act as a positive feedback, further increasing ice sheet melting (Bronselaer et al., 2018). For marine-terminating glaciers, the grounding zone—where ice sheets transition from being grounded on the continent to a floating ice shelf—is particularly susceptible to ocean warming, which can exacerbate mass loss and lead to further meltwater input (Bradley and Hewitt, 2024; Payne et al., 2021; Robel et al., 2022), So far,

the role of warmwater intrusions near grounding zones, and whether future inputs of meltwater will strengthen or weaken subsurface warming, has been primarily explored in models (e.g., Beadling et al., 2022; Bradley and Hewitt, 2024). Yet the model-predicted sensitivity of ice sheets to warmwater intrusions (e.g., Bradley and Hewitt, 2024) needs to be better constrained with observations around and upstream of grounding zones, and the role of meltwater in controlling the exchange of water between the Antarctic shelf and open ocean requires a better characterization of the currents and cross-slope exchange in this region (Beadling et al., 2022). Water column structure in and around the Southern Ocean impacts the physical processes that drive heat and carbon exchange but can also alter the efficiency and major pathways of the biological carbon pump (Lacour et al., 2023), with consequences that are currently not well understood but may be predicted from past records of Southern Ocean productivity.

Ocean Surface Turbulence

On the other end of the scale of physical processes that impact ocean heat uptake are small-scale turbulent processes near the ocean surface that act to control the transfer of heat, moisture, and dissolved greenhouse gases between the ocean and atmosphere (Dong et al., 2024; MacKinnon et al., 2016, 2021; Seo et al., 2023; Su et al., 2018; Whalen et al., 2020; Wu and Mahdevan, 2024; Yu, 2019). Although global models generally parameterize these as one-dimensional mixing processes (on both the ocean and atmospheric side of the interface), recent observations have shown that turbulence often has a fully three-dimensional geography, varies substantially on meso- and submeso-spatial scales and can lead to strong nonlinear coupling between the ocean and atmosphere on scales that are poorly measured and understood. Resolving these gaps will require new types of intensive, coordinated, multiplatform observations and new numerical and analysis techniques (including machine learning) to be depicted in the models.

These and other advances will help reduce the uncertainties in model forecasts of how carbon and heat uptake may change in the future, globally and spatially. Such an enhanced understanding will also contribute to improving model forecasts of changes in ocean circulation and other processes that affect marine ecosystems. As such, understanding potential changes in carbon and heat uptake represents both a vital and an urgent priority (as defined in Box 1.3 in Chapter 1) for the ocean science research community.

Societal Relevance and Broader Impacts of This Research

It cannot be assumed that the ocean will continue to provide the key climate, heat, carbon and associated societal services that it does presently. There is clear evidence that changes in the efficiency of these processes are very likely to occur and that, while the extent and character of these changes are uncertain, significant disruptions to ocean heat transport and carbon uptake are inevitable. It will be necessary for society to evaluate such changes in the ocean system as it considers the impacts of Earth system changes that are likely in the coming decades.

Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal

The growing field of ocean geoengineering aims to increase the amount of atmospheric carbon uptake by the ocean by enhancing the ocean’s natural capacity to absorb and sequester carbon, referred to as marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR; NASEM, 2022a). Many groups are already exploring mCDR techniques but from a limited knowledge base. There is little clarity on how to determine the success of such experiments, the associated hazards and unintended consequences, or the wider societal benefit that may or may not be associated with their widespread application (NASEM, 2022a). The ocean science research community has a critical role to play in conducting basic research to answer fundamental questions regarding the viability of any mCDR approach, including continuing long-term observations on the ocean’s natural carbon uptake mechanisms and their impact on ecosystems, as well as developing tools to verify the efficiency and effects of proposed mCDR strategies. Important questions for researchers to address are whether the ocean’s natural CO2 removal and sequestration processes can be sped up safely and at a scale that would

help reduce the emissions deficit; whether the scale needed to make an impact is possible; and, if scale-up is possible, how the carbon cycle processes can be measured to verify removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Transdisciplinary research through strategic partnerships is needed to evaluate the cost-benefit trade-offs for the ecosystem and for the communities affected by potential mCDR activity.

Earth System Science

The research proposed within the ocean and climate theme will stimulate the development of new understanding of physical, biological, geological, and chemical processes in the ocean and the links between these fundamental components of the Earth system. Other connected disciplines will include engineering (new platforms and technology), mathematics, computational and computer science (data analysis and modeling), biology (organismal issues), and many others. Additionally, the cross-cutting issues that will need to be addressed to answer the research questions in this theme will require new, transdisciplinary studies that will be supported by the training and education of a new cadre of early career researchers. The results of this work will support the growing understanding and awareness of society as to the scope and scale of the changing ocean and what this means in terms of weather patterns and extremes, sea level rise, and the health of coastal waters and the nutrients harvested within. The research will lead to understanding that may guide the development of new policy around mitigation and adaptation strategies for responding to those changes.

Observations, Tools, Technologies, and Human Resource Needs

The observational needs of this research endeavor will require developing new sensors to measure key ocean variables and applying these sensors on platforms, such as Argo floats and other autonomous observing systems, that are already in use, as well as new platforms and approaches to remote ocean observing. These innovative developments will stimulate the commercial sector to further market new technology for the growing need to measure variables that can quantify heat and carbon uptake and redistribution in the global ocean.

Regional- and Global-Scale Observations

A wide range of process studies in key regions needs to be combined with regional- and global-scale surveys for measuring key ocean variables, including heat, salinity, carbon, oxygen, and other physical, biogeochemical, and ecosystem variables. These measurements will enable better understanding of the ocean, which will support the calculation of key fluxes used in regional- and global-scale forecast models. The data from these large-scale surveys can be used to both initialize and calibrate these models. A good example of such a global-scale survey is the autonomous float program Argo, which is presently being expanded from a primary focus on measuring only the surface heat and salinity (Argo) to include biogeochemical measurements (BGC-Argo), acoustics (Passive Acoustic Listeners), and measurements over the full ocean depth (Deep Argo). However, full process studies, which are necessary for quantifying key ecosystem fluxes, will still need to rely on the use of a modernized U.S. Academic Research Fleet for more specialized measurements.

Model Development and Data Management

A key part of this work will be developing new models that both build upon existing models and apply new modeling techniques, including innovation associated with using high-performance computing software and artificial intelligence. Investments in collecting measurements on different temporal and spatial scales—including global circulation and air–sea exchange—and data curation to support new advances in data assimilation, machine learning, and hybrid methods are particularly relevant to advancing these models. The models needed to do this work include high-resolution regional models paired with biogeochemical

and biological models and coupled ocean–atmosphere climate models that also include key biological and biogeochemical systems. No single-model architecture will be able to ingest and analyze the amount of data needed to understand these questions. This enhanced modeling will require better coordination, integration, and curation of data from all sources, as well as collaboration with other agencies and international partners for an effective approach to data management.

Paleoceanographic Records

Long-term datasets are necessary for deciphering the periodicity of natural climate variability that occurs on timescales that can obscure the changes associated with anthropogenic warming. Furthermore, the climate periods that are most analogous to current global temperatures and/or atmospheric CO2 concentrations are more than 100,000 years in the past and as far back as several million years in the past (Anderson et al., 2024; Shackleton et al., 2020). In this context, direct observations of global climate from less than a century ago provide too little data to adequately assess whether the advanced models are accurately simulating Earth’s climate at greenhouse gas levels significantly higher (or lower) than present. Most notably, climate archives preserved in subseafloor sediment cores recovered by scientific ocean drilling are critical to ground-truthing theories on the dynamics/coupling of the climate system and the carbon cycle (see Figure 3.4 in the Interim Report [NASEM, 2024b]), as well as the nature of tipping points. For example, evidence continues to emerge on key details (timing/patterns and lead–lag relationships) of past changes in ocean overturning circulation, particularly the history of AMOC, a major contributor to heat redistribution over the last several million years of glacial–interglacial cycles. This information, along with new paleoceanographic data on changes in North Atlantic and Arctic sea ice distribution, are enabling identification of the temperature and salinity thresholds that trigger major shifts in the intensity of AMOC (e.g., Ait Brahim et al., 2022; Walczak et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021). These findings, along with new ocean drilling records from geographically sensitive regions and analogous time periods and more detailed modern observations, will be key to testing and improving models that are forecasting a rapid reduction in the strength of AMOC in the coming decades and for forecasting impacts on regional climates (e.g., cooling of England and Scandinavia and possible hydrological shifts, such as monsoon system changes).

Additional paleoceanographic evidence of the modes of ocean circulation present in a warmer world, as well as the ocean’s role in regulating the carbon cycle (and climate), can come from scientific ocean drilling investigations of more ancient episodes (e.g., early Cenozoic and Cretaceous) of extreme greenhouse periods in Earth’s past. For example, sediment cores recovered from the Antarctic margin and elsewhere are providing critical constraints on the evolution of the East and West Antarctic ice sheets (e.g., Marschalek et al., 2021), which—along with the latest reconstructions of past variations in greenhouse gas levels (The Cenozoic CO2 Proxy Integration Project Consortium, 2023)—point to the potential for rapid responses (i.e., tipping points) to future warming. Further constraining the rates of change and the processes that trigger rapid ice sheet decay, such as interactions between warm(er) ocean currents (resulting from circulation changes) and marginal marine ice sheets and ice shelves (Sproson et al., 2022), are important areas for ongoing ocean science research.

Novel Sensors and Platforms

As discussed above, process and regional studies of heat and carbon will require the development of new sensor and platform systems to support the observational programs to collect the data needed. For example, biogeochemical sensors used to measure carbon are either very limited or unavailable. While some approaches, such as the Wendy Schmidt Ocean Health XPRIZE for pH measurement (Okazaki et al., 2017), have been effective in developing a particular sensor type (making a specific type of measurement), such innovation often takes years to decades and has not always led to quick commercial adoption followed by widespread availability of the critically needed sensors. Those making efforts to develop new technology need to look beyond the initial development phase and consider making such systems available to the ocean observers seeking to make the measurements.

Geographic Priorities

Regional studies need to focus on specific areas relevant to ocean climate and carbon cycling, including the convection regions of the North Atlantic; the Southern Ocean; upwelling regions (e.g., Eastern Boundary Currents and the equatorial Pacific Ocean); equatorial regions (e.g., hurricane formation sites in the tropical Atlantic); and coastal and estuarine regions, where freshwater mixing stimulates production. Those designing such region-focused studies need to carefully consider the balance between having a large-scale geographic focus on inventory analysis (e.g., surveys of carbon and nutrient concentrations) and ground-truthing with the need for process studies (e.g., quantifying carbon fluxes to the deep ocean).

Coupled Physical–Biological Models

In addition, carbon budgets are intrinsically linked to ocean life: the dynamics, ranges, and abundance of species, from viruses to whales. Models that include the species that affect carbon cycling, acquisition, and release are fundamental to success, as are models that parameterize fluxes within food webs. There is a need for further model development on ways to assess, measure, and sense ocean life at the species level in the world’s ocean and incorporate this understanding into the models in such a way that they are accurately represented as parameters in the climate models.

Workforce Development

Common to all three urgent research themes, and discussed further in Chapter 3, the groundbreaking research required to resolve these societal challenges will require new cohorts of transdisciplinary researchers and ocean management professionals. In particular, local communities and their resource managers play a crucial role in directing effective research and in using research to formulate practical solutions to local problems. New approaches to providing education, training, and development are key to the scientific process, including in regional and global scale studies. The transdisciplinarity of these themes spans the classical branches of ocean science—biological, chemical, geological, and physical—but also includes ocean engineering, genomics, and computer science, as well as—given the themes’ societal relevance—social sciences and humanities, when appropriate. The need for transdisciplinary research to be collaboratively developed with multiple interest holders and communities is described further in Chapter 3.

ECOSYSTEM RESILIENCE

How will marine ecosystems respond to changes in the Earth system?

Ecosystem resilience, broadly speaking, refers to the capacity of an ecosystem to absorb repeated disturbances or shocks and adapt to change without fundamentally switching to an alternative stable state (Holling, 1973). One of the most highly referenced research papers on the topic of coastal ecosystems discussed the existential threats that disturbances—in particular, eutrophication and overfishing—pose to marine food webs (Jackson et al., 2001). This and other research studies emphasize the connectivity among

organisms and environment, and how environmental impacts can lead to ecosystem state change, including collapse. Drawing on evidence from highly studied ecosystems and long-term datasets, these studies increased understanding of how ecosystems resist and recover from environmental change, and the points at which they can shift to a highly altered state (Heinze et al., 2021). The message of this and related research papers is that life in the ocean will go on despite tragic impacts, but it may do so in a manner so different from present conditions that it lacks much of what humanity values.

Understanding the resilience of marine ecosystems to environmental changes remains a significant challenge. A key component of the challenge of understanding ecosystem resilience is deciphering the patterns of species’ distribution and abundance across space and time, commonly referred to as biogeography, which depend on species-specific interactions, growth rates, predation, and environment changes and resource availability. Early advances in marine ecology have provided foundational concepts of how ecosystems function, including the ideas that the presence of some “keystone” organisms play an outsized role in the function of whole systems, that species diversity increases ecosystem resilience, and that microbes play a fundamental role. These fundamental theories benefit from examination in the context of the wide range of habitats and rapidly changing conditions in the global ocean.

It is also important to consider the physical, chemical, and biological connectivity among marine ecosystems. There are many examples of the depth of interconnection among variable ecosystems and how they bolster one another. For one, vertically migrating animals mix stratified waters (e.g., the epi- and mesopelagic) and move nutrients and carbon between deep and surface zones, providing nutrition for bathypelagic and benthic organisms (Wirtz and Smith, 2020). Coastal coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds and marshes support seashore communities through nursery protection of young fish, nutrient provision, but also by dissipating wave energy delivered to shorelines and minimizing damage. Equally important viruses, bacteria and archaea, and protists play critical roles in the ocean biogeochemistry that affects nutrient availability and productivity among all ecosystems (e.g., Holt et al., 2023; Shah Walter et al., 2018; Suttle, 2007).

These complex issues of ecosystem stability play a huge role in impacts of marine fisheries, coastal habitats, biodiversity, and global climate impacts on humanity. Advancing the understanding of those factors that confer or undercut ecosystem resilience also enhances humanity’s ability to manage—and when necessary, adapt to—changes in marine ecosystem functionality.

The challenge for the next decade is to understand biological communities and their functions in the ocean over multiple temporal and spatial scales. These understandings serve as both sentinels to change and ciphers for how change will emerge under different environmental pressures. This includes the need to predict when ecosystems can and cannot recover from disturbances. Not only is it essential to understand how ecosystems have responded in the past, but there is a strong need to develop the ability to forecast how ecosystem structure function and biodiversity will respond to changes in the Earth system in the near future. As a result, scientific research to establish a basis for change trajectories in ecosystems is vital, and research to forecast where trajectories lead for these ecosystems, especially those that humans depend upon, is urgent. Addressing these themes through a transdisciplinary research lens will create the foundation for understanding of how changing physical, climate, and social environments affect the interdependent relationships between humans and ocean.

Background and Context

What enables a marine ecosystem to be resilient in response to change is an area of significant scientific inquiry (e.g., Ma et al., 2021). Foundational questions remain, in both well-studied systems such as temperate fisheries, coral reefs, and marshes, and less-studied areas such as the deep ocean and hard-to-reach locations (e.g., beneath sea ice in polar regions, seamounts). Ongoing NSF investments in ocean monitoring and long-term ecological studies help set the context for understanding how species and ecosystems respond to natural and anthropogenic environmental change.

Key Concepts in Understanding Ecosystem Resilience

In conducting research on resilience, the three fundamental “Rs”—resilience, redundancy, and resistance—are key to understanding how change will impact ecosystems and the services they provide (Levin and Lubchenco, 2008). Ecological resilience focuses on the capacity of an ecosystem to absorb and adapt to disturbances while maintaining typical structure and function (components and processes). Closely affiliated with resilience is redundancy, the ability of one taxon to play the same important ecosystem role as another, and resistance, the ability for taxonomic composition to remain unchanged in the face of a disturbance (Allison and Martiny, 2008; Levin and Lubchenco, 2008). The facets that delineate variability in these three Rs also warrant more attention.

A parallel concept to resilience is tipping points (Selkoe et al., 2015), or the stress levels at which ecosystems shift rapidly in terms of biological structure and function. Using these scientific concepts to learn more about the dynamics of ocean ecosystems will translate directly to reducing the uncertainty in predictive models forecasting when and how ecosystems change. Accordingly, this research topic is a priority for the ocean science community, spread across myriad ecosystems and millions of species that make up ocean life.

The Importance of Biodiversity in Conferring Ecosystem Resilience

One important facet underpinning ecosystem resilience is the biodiversity inherent within an ecosystem. Biodiversity effects on ecosystem resilience have been a pivotal topic over the past decade, with a series of studies showing that resilience to environmental change is bolstered in habitats with a large number of species (Duffy et al., 2016; Gamfeldt et al., 2015; O’Leary et al., 2017; Palumbi et al., 2009; Stachowicz et al., 2007; Vasileiadou et al., 2024; Worm et al., 2006). Moreover, the rate at which ecosystems recover from perturbations may be accelerated in habitats with greater biodiversity (Lotze et al., 2011). Specifically, it has been posited that ecosystem resilience is conferred when a diversity of organisms in a given habitat can carry out the same ecosystem processes or roles . This functional redundancy has been studied across many habitats using food web analysis, lipidomics, metatransciptomics, and metagenomics (e.g., Allison and Martiny, 2008; Galand et al., 2018; McParland et al., 2024; Sher et al., 2024). Continued studies of functionality are necessary, however, to identify ecological tipping points, where ecosystems can no longer recover to a prior state because of structural shifts in community composition that result from a loss of both biodiversity and function. Such research may be especially important in coastal habitats such as coral reefs, salt marshes, and mangroves where an inability to recover has a major effect on human coastal communities (e.g., Laurance, 2013). More remote ecosystems, such as deep-sea benthic systems, are also impacted by human activity connected to natural resource extraction (oil and gas, critical minerals) and may respond in ways that are difficult to predict, given the relatively more limited study of these places. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill is an excellent example of the importance of addressing knowledge gaps in ecosystem resilience in the deep sea to enhance science-based decision making.

While the understanding of these processes in animal communities is growing, the role of biodiversity and functional redundancy in marine microbial communities is not as well understood for a variety of reasons. First, the physiological repertoire of microbes (specifically, bacteria and archaea) is far greater than that of animals. Second, the mobility of genes among microbes may provide greater resilience to, for example, viral infection within a microbial mat (Hwang et al., 2023). In some cases, microbial communities maintain high biodiversity even when carrying out a limited set of metabolic pathways, which may confer resilience (Louca et al., 2018). How resource-limited conditions—such as the open, oligotrophic ocean—can maintain unexpectedly high diversity is paradoxical (Galand et al., 2018), highlighting the importance of further studies of resilience across taxonomic domains.

The important role of biodiversity in the ocean contrasts starkly with the increasing threats to biodiversity and unprecedented rates of decline. Worldwide, more than 25 percent of plant and animal species are estimated to be at risk of extinction (International Union for Conservation of Nature [IUCN], 2012). In the ocean, unsustainable fishing practices, climate change, and pollution are leading drivers of biodiversity

loss within ecosystems (Jaureguiberry et al., 2022). These losses are characterized by declines in population sizes of many species and extents, as well as the growth of “ecological generalists and disturbance-adapted species” in lieu of endemic species (IPBES, 2019, p. 3). In light of the aforementioned research relating biodiversity to ecosystem resilience, such losses raise the possibility that ecosystems will continue to be more vulnerable as rates of extinction increase. Improving understanding of direct and indirect drivers of biodiversity loss, as well as means of its prevention and remediation, is a key scientific priority in ocean science.

Molecular Genetics Tools for Understanding Ecosystem Resilience

Global surveys—such as the yearlong expeditions of the research schooner Tara—demonstrate how ocean biodiversity can be assayed using combinations of traditional tools (e.g., morphological) and evolving molecular genetics tools (Sunagawa et al., 2020). In the past decade, however, the use of molecular tools to study ecosystems has expanded through use of DNA for monitoring (Garland et al., 2023; Shum et al., 2019; Stat et al., 2017), strengthening the ability to enumerate biodiversity across taxonomic groups, and thus providing quantitative, reproducible data on the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem resilience. Such tools have also been used to measure ancient eukaryotic DNA in ocean sediments (sedaDNA). These new measurements open the possibility to understand ecosystem-wide changes and paleoenvironmental insights across major climatic transitions, including past eras of rapid ocean warming (Armbrecht et al., 2022; Crump, 2021; Harðardóttir et al., 2024). These recent results also establish a relationship between habitat biodiversity and the resilience and productivity of marine ecosystems.

Biodiversity, Resilience, and Connectivity in Distinct Ocean Habitats

Deep Sea Ocean depths below 200 meters (meso, bathy, and abysso pelagic zones) represent Earth’s largest habitat and harbor tremendous animal and microbial biodiversity (Paulus, 2021; Rex and Etter, 2010). Some studies suggest that only two-thirds of deep-sea biodiversity has been identified, yet these and remaining undiscovered species are under threat from anthropogenic activities (Costello and Chaudhary, 2017). Moreover, the deep sea provides a stunning array of ecosystem services that support upper-ocean productivity, including commercially relevant activities (Jobstvogt et al., 2014; Orcutt et al., 2020; Thurber et al., 2014).

Coral Reefs Coral reefs constitute only about 1 percent of the ocean surface but are home to about 25 percent of known ocean species. They tend to have much higher productivity than expected for oligotrophic waters, largely because of the symbiosis between reef-building corals and dinoflagellates (Symbiodiniaceae). Scleractinian corals have been a dominant ecological taxon for 250 million years, yet they have been strongly affected by past planetary periods of high heat and low pH (e.g., the Paleocene-Ecocene Thermal Maximum; Kiessling et al., 2024), making them an important group to study climate impacts on biodiversity and resilience. Reefs also are affected strongly by current climate-driven heat waves and are a model system for understanding the potential for adaptive evolution (Bay et al., 2017; McManus et al., 2021).

Open Oceans Offshore habitats from the poles to the tropics shelter a wide variety of species fundamental to fisheries, carbon flow, and production by photosynthetic plankton. The microbial loop in the open ocean can play a large role in carbon cycling within and between systems (see Gilbert and Mitra, 2022). It is also a place where the transient movement of organisms, including large migratory whales, sharks, fish, and turtles, impacts system resilience and interactions.

Polar Seas Both Arctic and Antarctic habitats have a wealth of species adapted to strong seasonal changes in productivity and to cold conditions. These span microbiomes, microplankton, intermediate grazers such as krill, and migratory predators such as baleen whales. These locations are important for study of ecosys-

tem resilience with examples of recovery, such as whale populations that recovered after aggressive whaling in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries (Savoca et al., 2024); such examples can inform future efforts to understand ecosystem resilience.

Resilience and Connectivity Among Marine Ecosystems

Ecosystems resilience is intertwined with the ability to resist change. Such resistance is often connected to the import and export of taxonomic groups and their associated function. For example, sharks connect reef ecosystems (Dixon and Gallagher, 2023), but their overall contribution to ecosystem resilience remains unclear in many cases. Change in the ocean is connected to both direct and indirect modifications to ecosystems (Watson et al., 2018). Direct modifications include the progressive addition of built and modified habitats in the ocean, known as ocean sprawl (Bishop et al., 2017). These additions stem from natural resource (e.g., energy, aquaculture) activities that have grown logarithmically in shelf, slope, and deep-sea environments since the 1980s (Bugnot et al., 2021; McCauley et al., 2015) and are expected to continue to rise, impacting ecological connectivity in populations spanning whales, fish (Firth et al., 2016), and microorganisms (Hampel et al., 2023). Habitat type and density can speed or impede the movement of organisms between habitats (Bishop et al., 2017) and change their biological character. Macroscale installations on the coasts and seabed (e.g., coastal and energy infrastructure, shipwrecks) are also joined by debris accumulating in the ocean for thousands of years (Amon et al., 2020; Lebreton et al., 2024) with unknown ecosystem impacts, and that may confound focused studies of natural history of naturally occurring deep-sea habitats (e.g., seeps, vents, seamounts).

An example of an indirect modification is eutrophication and the frequently associated changes in the supply and form of organic carbon to the coastal ocean. Such changes have been shown to impact taxonomic composition and life habitat (free living vs. particle attached) of bacterioplankton (Crump et al., 1999), which may be consequential to turnover of carbon in the ocean through the microbial loop, the expansion of oxygen minimum zones, and the export of organic carbon to the deep ocean. How eutrophication interacts with the movement of organisms and how it influences ecosystem resilience are open questions, even after decades of study, that rise in importance when microhabitats, including plastics, are considered.

Societal Relevance and Broader Impacts of the Research

The ocean maintains the habitability of Earth’s biosphere and confers environmental stability upon which humanity depends heavily. The next decade of studying marine ecosystems must include forecasting how changing marine environmental conditions will affect ecosystem resilience and thus impact human communities (and vice versa).

Basic research that informs topics affecting the blue economy, such as food security and long-term resource sustainability, may be particularly valuable. For example, targeted short- and long-term studies of ocean warming, acidification, and deoxygenation across a variety of spatial and temporal scales can help provide the information necessary to anticipate adverse effect on marine ecosystems and the downstream consequences of those effects on other communities, including humankind (see Feeley et al., 2010). Moreover, developing more robust models for predicting the weakening of the biological pump/export production—and how this will affect trophic structure, function, and movement of organisms—is key. Such models require fine-grained understanding of the full suites of ocean biodiversity and how these complex communities intersect with environmental conditions. While this may be aspirational, it prioritizes research areas and will help in conservation efforts, coastal protection, fisheries yields, and food security (e.g., Laurenceau‐Cornec et al., 2023). Co-developing technologies for rapid measurement and assessment of ocean biological and functional diversity could be prioritized, specifically technologies that allow for more rapid, higher-fidelity assessments of species-level biodiversity (e.g., advanced environmental DNA technologies [Takahashi et al., 2023]), as well as function (e.g., advanced technologies for measuring metabolic processes). Understanding matter and energy transfer in and across marine ecosystems, as well as to the continents, will help us better identify the environmental stressors that threaten resilience (e.g., Hoehler et al.,

2023). Finally, studies that better quantify the coupling of benthic and pelagic processes, as well as the coupling across pelagic zones, are essential to understanding how marine ecosystems are linked across ocean biomes. Moreover, they will provide the information necessary to understand the nature and extent of anthropogenic activities—such as deep-sea mining and its midwater pollution—on scales that transcend single-ocean ecosystems (Box 2.3; Drazen et al., 2020). NSF is uniquely situated to support basic research, including that with direct relevance to application, to establish a framework for thoughtful, well-informed discussions about anthropogenic impacts on marine ecosystems.

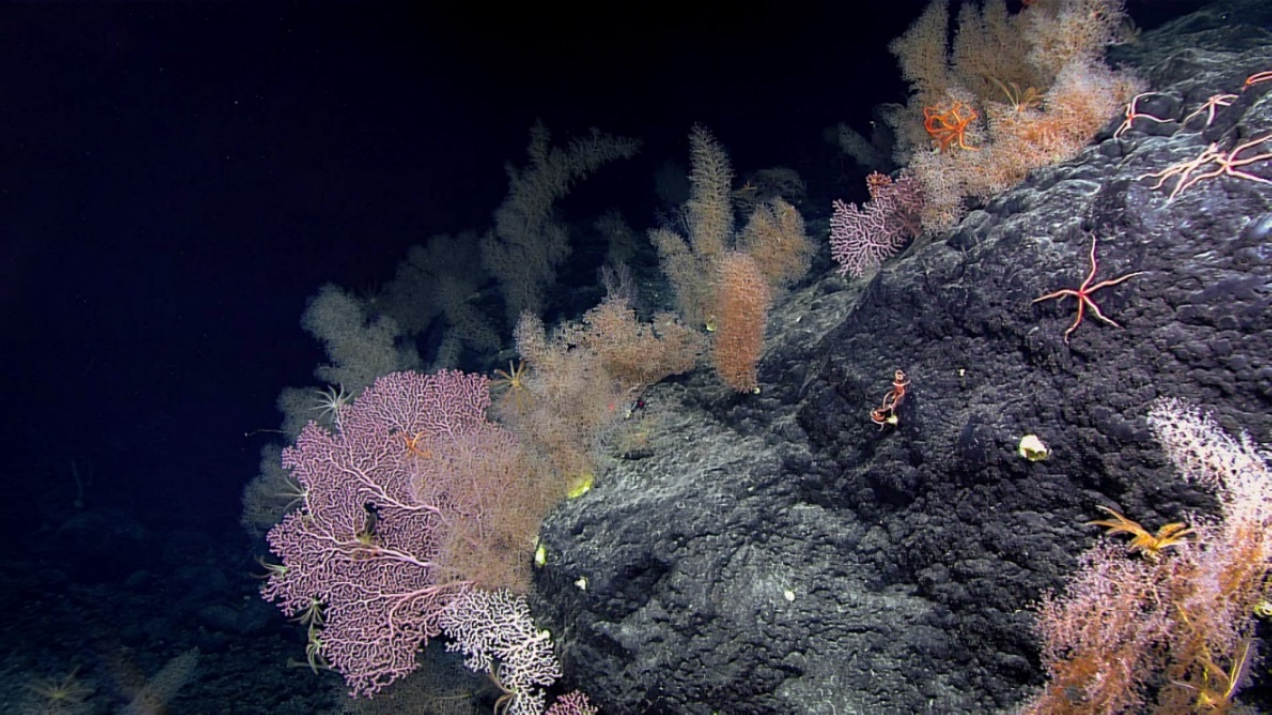

BOX 2.3

Potential Impacts of Deep-Sea Mining

SOURCE: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Exploration and Research, Deep-Sea Symphony: Exploring the Musicians Seamounts.

Deep-sea mining likely has an outsized impact on deep-sea animals, which are adapted to the low-nutrient, low-disturbance conditions (Figure 2.6). These organisms are not equipped with the physiological or biochemical capacity to cope with increased suspended particles, changes in pH or oxygen, and physical perturbation that will almost certainly arise from seabed mining (e.g., Grégoire et al., 2023). Moreover, mining will very likely produce particulate plumes that will reside in the overlying water column (Christiansen et al., 2020). These nano- and microparticles of minerals can have severe impacts on pelagic organisms, especially larva (Drazen et al., 2020). It is equally likely that suspended mining particles will impact commercially relevant species as well. A number of small-scale seabed mining studies support these conclusions (Voonahme et al., 2020), but broadly speaking, there is a massive lack of baseline data (Le et al., 2022), making it difficult to provide quantitative estimates of these impacts and making it easier for mining advocates to misrepresent or disregard existing data.

The demand for rare earth elements will likely fuel continued interest in deep-sea mining. Developing a robust, comprehensive understanding of the potential benefits and costs of seabed mining depends on continued deep-sea research, including on the connectivity between benthic and pelagic zones. Studies to date suggest that the impacts of seabed mining have the potential to be widespread, including impacts on deep-sea biodiversity, deep-sea ecosystem services, and comparable impacts on mid- and upper-ocean ecosystems.

Techniques, Tools, Technologies, and Human Resource Needs

Defining the key functions of healthy ecosystems and understanding what enables an ecosystem to be resilient requires multiple perspectives from the experimental to the societal and will take advantage of a varying set of skills, interests, and investments in capacity. A broad swath of data from many disciplines is required to convey a cohesive understanding of facets that govern ecosystem health. For example, understanding the ecosystem will require extensive data processing of biodiversity patterns across taxa for the dynamic patterns to seed future forecasts and mechanistic hypothesis testing.

Measuring Biodiversity Resilience

The explosion of molecular tools in the past decade has expanded the capability to monitor whole-community dynamics spanning all three domains on the tree of life: bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, and to simultaneously delve taxonomic composition, potential function, and expression of function. Tools that provide results of this nature—such as advancements in environmental and organismal DNA, -omics, and bioinformatics—need to be explored and developed to expand monitoring capacity (Chen et al., 2024; Hendricks et al., 2023). Such capability is necessary if metrics of biodiversity are to be included in forecasting products, and to measure and communicate how ocean change directly affects ecosystem services supported by biodiverse marine ecosystems. However, these techniques remain time and resource intensive and do not provide instantaneous or in situ data. Biosensors for specific taxa (e.g., harmful algal blooms, copepods, pelagic fish, many others) need to be developed to provide dynamic measurements of specific ecosystem components.

Highly productive ecosystems often have lower alpha diversity (e.g., hydrothermal vents and seeps, upwelling ecosystems) due to dominance by few taxa; and research strategies must therefore incorporate concepts of bloom dynamics alongside productivity to better understand biodiversity patterns. Moreover, there is a paucity of technologies for measuring metabolic rates in situ, especially automated technologies. Such technologies would enable a more direct assessment of function and activity that could be related to biodiversity indirectly. In addition, artificial intelligence–enabled video documentation and annotation, coupled with molecular techniques, may further enhance the ability to quickly assess patterns of biodiversity across space and time.

Food Web Dynamics and Emergent Ecosystem Properties

Food web dynamics are fundamental reflections of ecosystem function and resilience. Food web construction and exploration relies on correct identification of species and their diets in complex marine ecosystems (Paine, 1966). This is a serious challenge in complex ecosystems with thousands of predatory and prey species. This problem has required significant simplification of datasets in the past but can now be better managed using the molecular techniques mentioned above. When those approaches are coupled with trait-based or theoretical-based estimates of species interactions (Brose et al., 2019; Krumhardt et al., 2024; McGill et al., 2006; van Denderen et al., 2021) and biogeochemical measurements, they may afford enhanced opportunities to construct marine food webs with greater depth and realism.

Modeling marine food web interactions with improved skill and accuracy is needed in the next decade. In the past, this modeling has relied on simulation testing and sensitivity analysis to advance and critique hypotheses and to calibrate, validate, and verify modeling of marine food web responses to a wide range of phenomena (Coll and Lotze, 2016; Fulton et al., 2011, 2019; Heymans et al., 2014; Libralato et al., 2019). In fact, marine food web models have established international best practices, which are being increasingly considered in applied research (Craig and Link, 2023; Fulton et al., 2011; Heymans et al., 2016). Coupling food web models, however, to other models of oceanographic features remains a challenge, as does coupling them with socioeconomic models. In addition, most food web models do not include microbial components of the ecosystem; if they are included, they are poorly parameterized. Emergent and cybernetic

features of systems thinking may also be helpful to understand ecosystem resilience holistically (Sunagawa et al., 2020).

Insights gained from systematic views of marine ecosystems result in perspectives that would have been missed otherwise. Emergent features of marine ecosystems, such as rapid shifts in species composition or abundance, can serve as early warning signals of approaching tipping points (Heinze et al., 2021). Knowing how well and how fast a system will respond to interventions or insults, such as oil spills, is now possible using cybernetic measures of resilience, including ascendancy, network measures, and trophic throughput (Lewis et al., 2021). Cumulative biomass and production inflection points across trophic levels can serve more effectively than species-level evaluation as early warning signals of responses to change (Libralato et al., 2019). Novel works on food webs and emergent properties will provide a more composite and comprehensive evaluation of ecosystem resilience.

Biological Teleconnectivity and the Geographic Scale of Ecosystems

The connectivity of biological populations at both small (Cowen et al., 2007) and large scales also influences ecosystem resilience. For example, animal tracking data show that migrating macrofauna (e.g., whales, seabirds) transit across ocean basins. There is growing evidence that some species’ populations can be exchanged and intermingled across these basins, such as the movement of marine invertebrates across the Arctic from the Pacific to the Atlantic during the Last Glacial Maximum (Palumbi and Kessing, 1991). Oceanographic connections through this gateway are projected to expand as the Arctic becomes more ice free, and also in response to decreased seasonal stratification of converging Arctic, Pacific, and Atlantic water masses converging in the Arctic and increased inflow of Atlantic and Pacific waters due to large-scale circulation changes. The ecological implications of these changes to ice cover and stratification are not well known at this time and will be difficult to model and predict without further study.

Many questions remain about connectivity, particularly at the base of the food web, spanning prokaryotic and eukaryotic plankton and how they move across ocean basins. Datasets on genetic diversity can help determine the degree of differentiation in populations across vast distances and the role of currents (Hamdan et al., 2012; White et al., 2010). Currents play a strong role in distribution of adaptive genes and the ability of ocean populations to evolve during rapid environmental change (e.g., McManus et al., 2021). An important step in the next decade is quantifying the global, basin, and regional scales of biological teleconnectivity. This will require developing more advanced ocean flow models and testing their ability to predict biological transport of larvae and juveniles. If global-scale, biological teleconnectivity does exist across the ocean basins, understanding the ramifications of genetic mixing, speciation, microevolutionary changes, food web dynamics, other species interactions, and even human dependencies upon these biota will be needed. The impact of such teleconnections may be further amplified in light of the influence of climate change on species distributions and changing water conditions.

The Role of Marine Paleobiology in Untangling Ecosystem Responses

A challenge to forecasting marine ecosystem responses to changes in the Earth system is that natural multidecadal variabilities in ocean conditions, and short records from direct observations, obscure the detection of longer-term trends (Gulev et al., 2021). Additionally, the best analogs for model scenarios of a near-future warmer world occurred at least 100,000 years in the past to several million years in the past (see Figure 3.4 in NASEM, 2024b; see also Rae et al., 2021). For these reasons, the analysis of high-resolution marine microfossils, molecular fossils (i.e., biomarkers), and sedaDNA preserved in subseafloor sediment cores collected by ocean drilling are key to understanding patterns of species’ distribution and abundance across space and time, changes in productivity, and other ecosystem functions and dynamics. Microfossil datasets provide the means to examine how ecosystems responded in the distant, but highly relevant, past warming ocean and to examine the acidification and deoxygenation of ocean waters. Microfossil records have informed predictive models on the vertical compression of habitats as the ocean warms and their expansion as the ocean cools (e.g., Crichton et al., 2023). Molecular fossils from Cretaceous subseafloor

sediments have shown that abrupt, sustained increases in primary production can trigger marine microbial reorganization from the surface waters to the seafloor, destabilizing carbon cycling and promoting progressive marine deoxygenation and ultimately ocean anoxia events (Connock et al., 2022). These paleobiological examples show how changes in plankton ecology and diversity, as well as microbial metabolic activity, could alter the efficiency of the ocean’s biological carbon pump (and thus its ability to absorb carbon) (Crichton et al., 2023; Henson et al., 2022). Other ecological concerns—such as determining whether there is an upper thermal limit for tropical habitability of phyto- and zooplankton as the planet warms and the extent to which poleward shifts may represent precursor signals that lead to extinction—would require new marine palaeobiological records to fully understand.

In summary, the next decade will continue to bring change (natural and anthropogenic) that significantly impacts the health and survival of marine organisms, marine ecosystems, and coastal communities. Transdisciplinary science that seeks to address and understand this change is needed, along with innovative and wide-ranging perspectives applied to the research. As a leader in the field of ocean sciences, the United States has a responsibility to facilitate these unique research approaches in this critical time of change.

EXTREME EVENTS

How can the ability to forecast extreme events driven by ocean and seafloor processes be improved?

The ocean provides many benefits to society, but it also generates extreme events that can be devastating to people and ecosystems. Examples range from coastal hazards, such as subduction zone earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, storm surges, and sea level rise, to phenomena that reach inland, such as monsoons, atmospheric rivers, and heat waves; these extreme events are often defining moments for communities. Likewise, extreme biological events, such as red tides, mass fish die-offs, coral bleaching, and the disappearance of 11 billion snow crabs from Alaska waters, can also disrupt or destroy local economies and ecosystems (Kruse, 2023).

While coastal areas, which are home to 40 percent of the U.S. population (NOAA, 2025a), often bear the brunt of ocean-based extreme events, impacts from large atmospheric phenomena, such as El Niño or the North Atlantic Oscillation, can also lead to extreme weather events across the entire continental United States. Developing the ability to forecast such events relies upon foundational scientific knowledge of the underlying causes of extreme events, which in turn will allow researchers to better assess and inform how changes in ocean conditions and ecosystems will impact society in the future. Many extreme events are increasing in frequency and/or intensity, making the need to understand their mechanisms and improve their forecasts both urgent and vital.

Background and Context

Societal vulnerability to extreme events, both in the United States and abroad, is profound. Society depends on massive, century-scale investments in infrastructure, including port facilities, commercial fishing, offshore energy, coastal development, municipal investments, national defense, and more. And, because the ocean is a major driver of climate, extreme events caused by the changing ocean threaten inland

regions as well, whether it be via flooding, supply of food and energy, or other threads of the social tapestry. Likewise, when human communities depend on the ocean as a food source, for protection from storm damage, or for healthy shorelines, collapse of ecosystems due to extreme events can disrupt individual livelihoods and entire economies.

In light of humanity’s dependence on the ocean, and the socioeconomic benefits of forecasting extreme events, improving the ability to forecast the occurrence of extreme events across spatial and temporal scales relevant to coastal communities is an urgent research priority.

Ocean-based extreme events fall into several broad categories (Table 2.2) and include phenomena acting over widely varying time and space. Specific examples of research pursuits to improve predictive capability include:

- Increasing the ability to model the future impact of global weather extremes, such as agricultural resilience and heat and flood preparedness.

- Forecasting the extent of deoxygenation and dead zones in the ocean, thus being able to anticipate their impacts on ecosystem health.

- Utilizing nature-based solutions that support societal adaptation and ecosystem restoration when forecasting responses to extreme events.

- Integrating existing and new data and knowledge from across disciplines and communities to improve the ability to respond to extreme events.

- Integrating existing and new data and knowledge to elucidate precursory signals that can improve forecasting of earthquakes, underwater volcanic eruptions, submarine landslides, and associated extreme events such as tsunamis.

TABLE 2.2 Categories of Ocean-Based Extreme Events

| Geophysical/Geological Hazards | Weather and Water-Related Hazards | Biological Hazards |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Societal Relevance and Broader Impacts of the Research

Earthquakes and Volcanism