Promising Practices for Addressing the Underrepresentation of Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Opening Doors (2020)

Chapter: 6 Recommendations

6

Recommendations

This report is not the first report of its kind. There have been many past reports published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and other groups that have described the factors that drive the underrepresentation of women in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) and have laid out the evidence-based steps that organizations and institutions can take to improve the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women in these fields (see Appendix B). Some institutions and organizations have intentionally implemented such policies and practices and seen great improvements in the participation of women in science, engineering, and medical education and careers. For example, following the release of the 2007 National Academies report Beyond Bias and Barriers: Fulfilling the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering, the National Institutes of Health formed the Working Group on Women in Biomedical Careers and created a grant program, Research on Causal Factors and Interventions that Promote and Support the Careers of Women in Biomedical and Behavioral Science and Engineering, which funded 14 institutions to directly address the recommendations in the report (Plank-Bazinet et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the issue persists at a national level.

This report concludes that entrenched patterns of underrepresentation in STEMM disciplines persist due to a range of factors, including: lack of broad awareness of the evidence-based practices reviewed in this report, a need for greater prioritization and resource allocation by institutions toward targeted, data-driven equity and diversity efforts, and because real progress on this issue will require culture change driven by systemic, coordinated efforts from a range of stakeholders—Congress, the White House, federal agencies, faculty, employees, academic administrators, professional societies, and others.

Below we offer a set of recommendations aimed at providing the appropriate incentive structures, grounded in the need for transparency and accountability, to allow these many stakeholders to work in concert to implement promising and effective practices to improve the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women in STEMM.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee’s recommendations are grouped into four broad categories, which are targeted at incentivizing and informing the broad adoption of evidence-based promising practices for improving the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women in science, engineering, and medicine:

- Driving transparency and accountability. Institutions must articulate and deliver on measurable goals and benchmarks that are regularly monitored for progress and publicly reported. Multiple studies have demonstrated that transparency and accountability are powerful drivers of behavior change.

- Targeted, data-driven approaches to addressing the underrepresentation of women in science, engineering, and medicine. Rather than guessing at the interventions that work best for all women of all intersectionalities across all disciplines, the committee recommends a targeted, focused, data-driven approach to closing the gender disparities in science, engineering, and medicine. Such an approach includes, for example, dissecting the challenges and barriers by discipline and career stage, acknowledging the fact that interventions and strategies that work well for White women may not work well for women of color, and using disaggregated data collection, analysis, and monitoring as the basis for constructing specific interventions within the unique context of a given institution.

- Rewarding, recognizing, and resourcing equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts. Equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts by institutions are often hindered by a lack of sufficient resources and by the expectation that individuals, particularly women and men of color, who care about these issues will take the lead on promoting positive change without compensation or real authority. Even more concerning is the fact that those individuals who take responsibility for promoting equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts may be penalized for devoting time and energy to such efforts if they take time away from other activities the institution prioritizes and rewards, such as securing research grants and publishing peer-reviewed papers. The committee recommends that institutions, both academic and governmental, sustainably allocate resources and authority to the leaders of equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts and provide incentives that communicate that the promotion of an inclusive scientific, engineering, and medical enterprise is everyone’s responsibility.

- Filling knowledge gaps. Although scholarly research on gender disparities in science, engineering, and medicine has yielded an abundance of information that can be applied toward reaching gender equity, there are critical knowledge gaps that require closer attention.

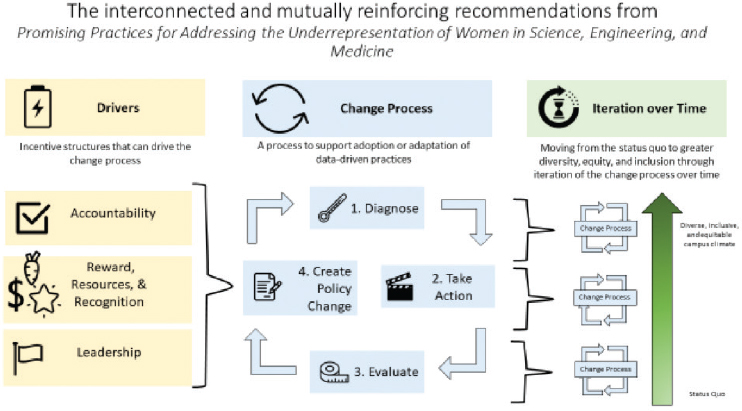

The rationale for the recommendations the committee offers within each category is rooted in the notion that there are certain levers of change that, if pulled, can drive greater, more widespread, systemic action. However, it is important to acknowledge that the four broad categories into which the committee’s recommendations are grouped are not, in fact, distinct, but instead are fundamentally interconnected components of a complex system of actors, incentives, and information (see Figure 6-1). For example, drivers of transparency and accountability yield new information that can inform targeted, data-driven interventions, while also acting as an incentive that can drive greater resource allocation for equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts. The committee contends that the interconnectedness of these recommendations underlies their strength. This is not to say that individual recommendations, if implemented by stakeholders, cannot have a tangible impact, but the systemic change that is needed to drive swift change on this issue is suited to a systemic approach.

In addition to high-level recommendations, the committee offers a series of implementation actions for each recommendation that are designed to provide stakeholders with specific, practical advice. In many instances, the committee intentionally developed these implementation actions such that they take advantage of existing infrastructure and activities, and sometimes modify them in specific ways, to facilitate the implementation of the recommendations.

I. DRIVING TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY

The legislative and executive branches of the federal government have the power to serve as drivers of transparency and accountability in the scientific, engineering, and medical enterprise. In Chapter 5, the committee found that transparency and accountability are critical levers for driving positive change in equity and diversity efforts. Therefore, the committee recommends several actions that can increase public transparency and accountability so that the nature, extent, and impact of federal agency and university efforts will ensure equity, diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity in the scientific, engineering, and medical workforce. As explained, these recommendations, while focused primarily on driving transparency and accountability, also serve other functions. For example, if implemented with fidelity, these recommendations can serve to highlight the extent to which each federal agency is making equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts a priority, and shine a light on whether such programs are properly resourced. Further, the implementation of these recommendations may provide the government and universities with information on the impact of the

Drivers: Transparency and accountability; rewards, resources, and recognition; and committed leadership can provide positive and negative incentives that increase the likelihood that institutions will take action and adopt a change process. Recommendations 1, 2, 6, 7, and 8 and their associated implementation actions are aimed at establishing such drivers.

Change Process: The process consists of four stages: (1) an institution, school, or department collects, analyzes, and monitors quantitative and qualitative data to first diagnose the particular issues they are having with recruitment, retention, and advancement of White women and women of color; (2) institutional leaders take action to address their shortcomings at the program, school, or department level by drawing upon the existing research and practice to adopt or adapt targeted, evidence-based approaches; (3) the institution, school, or department repeats the data collection and monitoring to determine whether the treatment has been effective or whether it is time to try a new approach; (4) leaders formally institutionalize effective practices through policy changes so they can sustain transitions in leadership, budget fluctuations, and other potential disruptors that could undermine the sustainability of the effort. Recommendations 3, 4, and 5 and their associated implementation actions are intended to support this change process. Recommendation 9, which calls for future research to fill knowledge gaps, will also support this process by providing additional information on the efficacy of certain strategies and practices.

Iteration over Time: The goal of the change process outlined above is to move from the status quo, in which women, and particularly women of color, are underrepresented in STEMM, to a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive STEMM enterprise. To achieve this outcome will require institutions to invest in an iterative cycle of action and evaluation that supports the development and, ultimately, institutionalization of strategies and practices that will work within the particular context of the institution. All of the recommendations offered by the committee are intended to support iteration over time to reach the ultimate goal of greater equity, diversity, and inclusion in STEMM.

various efforts by the federal agencies and universities to support greater equity, diversity, and inclusion in science, engineering, and medicine such that more successful programs could be scaled and amplified, while less successful programs could be improved or replaced.

There is considerable debate as to whether new public policies have their intended positive impacts. The answer, of course, is that it depends. Some government policies help some people they intend to serve, but might hurt others. For example, there is evidence that minimum wage laws do, in fact, increase the average incomes of current low-wage workers in communities where the laws are enacted. But there is still considerable uncertainty as to whether minimum wage laws have a negative effect on the employment rate (Allegretto et al., 2018; Jardim et al., 2017). Based on its extensive experience in observing the consequences of government policies over the past half-century, the committee recognizes both the potential for good and the very real limitations of government policy to drive and sustain change. In that context, we see government policies as one vital part of a systemic strategy to catalyze and incentivize the kinds of changes needed to open the doors to more women in STEMM disciplines and STEMM careers. Even if government policies only remove a few barriers, rather than mandate actions and impact that may be sufficient to create pathways for change that conscientious leaders can use to implement effective strategies and practices. It is in that spirit that the following recommendations are offered.

Recommendation 1.

The legislative and executive branches of the U.S. government should work together to increase transparency and accountability among federal agencies by requiring data collection, analysis, and reporting on the nature, impact, and degree of investment in efforts to improve the recruitment, retention and advancement of women in STEMM, with an emphasis on those existing efforts that take an intersectional approach.

Implementation Actions

Action 1-A. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF) co-chairs of the Subcommittee on Safe and Inclusive Research Environments of the Joint Committee on the Research Environment should annually catalog, evaluate, and compare the various efforts by the federal science agencies to broadly support the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women in science, engineering, and medicine. The director should task the subcommittee with publishing an annual, open-access report, modeled after NSF’s summary table on programs to broaden participation in their annual budget request to Congress, that documents existing programs at each agency, with a particular emphasis on those programs that take an intersectional approach, accounting for the experiences of women of color and women of other intersecting identities (e.g., women with

disabilities, LGBTQIA), and the qualitative and quantitative impact of these programs, using program evaluation metrics and data, when collected.1

Action 1-B. Congress should commission a study by an independent entity, such as the Government Accountability Office, to offer an external evaluation and review of the existing federal programs focused on supporting greater equity, diversity, and inclusion in science, engineering, and medicine. Such a study should result in a publication that documents the nature, impact across various groups, and prioritization of these programs, as described above, across federal agencies.

Recommendation 2.

Federal agencies should hold grantee institutions accountable for adopting effective practices to address gender disparities in recruitment, retention, and advancement and carry out regular data collection to monitor progress.

Implementation Actions

Action 2-A. Federal funding agencies should carry out an “equity audit” for grantee institutions that have received a substantial amount of funding over a long period of time to ensure that the institution is working in good faith to address gender and racial disparities in recruitment, retention, and advancement. Institutions could be electronically flagged by the funding agency for an equity audit after a certain length of funding period is reached. An evaluation of the representation of women among leadership should be included in such an audit. Equity audits should include a statement from institutions to account for the particular institutional context, geography, resource limitations, and mission and hold that institution accountable within this context. It should also account for progress over time in improving the representation and experiences of underrepresented groups in science, engineering, and medicine and should indicate remedial or other planned actions to improve the findings of the audit. The equity audit should result in a public facing report that will be available on the agency’s website.

Action 2-B. Federal agencies should consider institutional and individual researchers’ efforts to support greater equity, diversity, and inclusion as part of the proposal compliance, review, and award process. To reduce additional administrative burdens, agencies should work within the existing proposal requirements to accomplish this goal. For example, NSF should revise the guidance to grantees on NSF’s “Broader Impact” statements, and NIH should revise the guidance to grantees on the “Significance” section in the research plan to include an explicit

___________________

1 The committee recognizes that programs will have different metrics of success, depending on what the goals of the program are and that direct comparison of programs across agencies will not be possible. However, the evaluation will examine the data collected on the outcomes of the programs included and the extent to which the program met its goals.

statement on efforts by the prospective grantee and/or institution to promote greater equity, diversity, and inclusion in science, engineering, and medicine. While many grantees currently describe equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts as part of these sections of NSF and NIH proposals, historically, these sections of the proposals have served, first and foremost, to document the societal impact of the research (e.g. addressing climate change, curing cancer). The latter function of these sections of the proposal is critical and should not be replaced by the description of equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts. Rather this section of the proposal should be expanded to include commentary on both of these critical components of federally funded research. Moreover, these sections of proposals should be assessed and taken seriously in funding recommendations by review panels and funding decisions by agency personnel. If such sections of proposals are given different consideration by different institutes, departments, and directorates, effort should be made to standardize the weight rating given to these sections of the proposal across the agency. For example, the National Science Board could carry out a review of past NSF awards to determine how the NSF Directorates have accounted for gender equity, diversity, and inclusion among the metrics evaluated in proposals submitted to NSF.

II. TARGETED, DATA-DRIVEN INTERVENTIONS BY COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES2

In many ways, the recommendations in this section (particularly the many sub-recommendations under Recommendation (4) represent the most direct action items of this report. These recommendations are based on the committee’s analysis of years of research, data, and evidence on specific strategies and best practices that can improve the participation and advancement of women in science, engineering, and medicine.

The recommendations offered by the committee in this section also outline a change process. The process starts with an institution, school, or department collecting, analyzing, and monitoring quantitative and qualitative data to first diagnose the particular issues they are having with recruitment, retention, and advancement and then to take action to address their shortcomings by drawing upon the existing research and practice to adopt targeted, evidence-based solutions. The next step in the process is to repeat the data collection and monitoring to determine whether the treatment has been effective or whether it is time to try a new approach. The final step in the process is to formally institutionalize effective practices through policy changes so they can sustain transitions in leadership,

___________________

2 Because there is a significant academic orientation to this report—with college and university administrators being a primary audience—the committee has configured recommendations targeted directly to higher education leaders. Many of the ideas and recommendations here, however, can be easily adopted or adapted by private sector employers and government agency employers that also aim to close the gender gap in science, engineering, and medical fields.

budget fluctuations, and other potential disruptors that could undermine the sustainability of the effort.

The committee recommends a change process, rather than a single blueprint for change since there is no one-size-fits-all approach that will work in every institutional context. Institutions vary in mission, student demographics, student needs, and resource constraints and a particular strategy may work well at one institution and not well at another. For this reason, the committee recommends that institutions work to adopt or adapt the strategies and practice outlined in this report (see implementation actions 5 A-C) and iterate over time to develop an approach that will work well for their particular institution and the people it serves.

Recommendation 3.

College and university deans and department chairs should annually collect, examine, and publish3 data on the number of students, trainees, faculty, and staff, disaggregated by gender and race/ethnicity, to understand the nature of their unit’s particular challenges with the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women and then use this information to take action (see Recommendations 5 and 7 for guidance on specific strategies and practices leaders can adopt or adapt to address issues with recruitment, retention, and advancement, piloting and modifying them as appropriate, such that they are effective within the particular context of the institution).

Implementation Actions

Action 3-A. College and university deans and department chairs should collect and monitor department level demographic data, leveraging data already being collected by their institution in compliance with data reported to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) annually to determine whether there are patterns of underrepresentation among students, trainees, residents, clinical fellows, faculty, and staff, including in leadership roles. Specifically, deans and department chairs should request the following types of data and track these data over time:

- The demographic composition of the students currently enrolled and recently graduated in a given department or college. These data should be disaggregated by gender and race/ethnicity and should be tracked over time.

- The longitudinal demographic composition of the faculty disaggregated by faculty rank, department, gender, and race/ethnicity.

___________________

3 Except in cases for which reporting such data would publicly identify individuals and breach anonymity. For such data, the report should indicate that the numbers are “too low to report.”

- The longitudinal demographic composition of postdoctoral researchers, residents, clinical fellows, and staff scientists disaggregated by department, gender, and race/ethnicity.

This information should be used to adopt or adapt evidence-based promising and effective practices, taking into account the particular context of the institution (see Recommendation 5).

Recommendation 4.

College and university administrators should dedicate resources to carry out qualitative research on the climate in the school or department and the experiences of underrepresented groups and use this information to shape policies and practices aimed at promoting an inclusive climate and supporting underrepresented groups enrolled or employed at the institution.

Implementation Actions

Action 4-A. College and university administrators should work with an evaluator outside the relevant unit to support periodic climate research to assess the climate in the school or department in a manner that is methodologically sound, independent, objective, and free from bias and conflict of interest. Climate research can take the form of surveys, focus groups, and/or interviews.

Action 4-B. Given the extremely low representation of women of color in most science, engineering, and medical fields, administrators and external evaluators should work together to adopt a methodological approach that can protect the anonymity of such individuals and accurately capture their experiences. In some instances, interviews may serve as the most appropriate means to gather this information. It should be noted that, in some settings, researchers from a single institution may not be able to sufficiently protect the anonymity of women of color, who make up an extreme minority in certain fields, and so it may be best to conduct such research across an institutional system. Protecting sensitive, personal information will also be aided by the use of an external consultant that can hold the raw data and report only aggregated findings to the departmental leadership.

Recommendation 5.

Taking into account the institutional context, college and university presidents, deans, department chairs, and other administrators should adopt or adapt the actionable, evidence-based strategies and practices (see implementation actions 5 A-C) that directly address particular gender gaps in recruitment, retention, and advancement of women in science, engineering, and medicine within their institution, as observed by quantitative and qualitative data analysis and monitoring (see Recommendations 3 and 4 above).

Implementation Actions

Action 5-A. To work to improve the recruitment and retention of women in STEMM education, faculty and administrators in higher education and K-12 education should adopt the following approaches:

- Reorganize STEMM courses to incorporate active learning exercises (e.g., having students work in groups, use clickers) and integrated peer-led team learning.

- Promote a growth mindset by communicating to students that ability in STEMM fields can be improved by learning.

- Challenge stereotypical assumptions about the nature of STEMM careers by communicating to students that scientists often work in teams, conduct research focused on helping others, and have lives outside of work.

- Take steps to expose students to a diverse set of role models in STEMM that challenge the persistent societal stereotype that STEMM professionals are heterosexual, cis-gendered, White, men. For example, faculty and administrators should give assignments that require students to learn about the work of women who have made significant contributions to the field; work to ensure that the faculty in the department are diverse, such that students take courses and conduct research with people from a range of different demographic groups; and invest in educational materials (e.g., textbooks and other instructional media) that highlight the diverse range of people who have contributed to science, engineering, and medicine.

- Strive for gender-balanced classroom and group composition and take steps to promote equitable classroom interactions.

Action 5-B.4 To address issues with the recruitment of women into academic programs and science, engineering, and medical careers, admissions officers, human resources offices, and hiring committees should:

- Work continuously to identify promising candidates from underrepresented groups and expand the networks from which candidates are drawn.

- Write job advertisements and program descriptions in ways that appeal to a broad applicant pool and use a range of media outlets and forms to advertise these opportunities broadly.

- Interrogate the requirements and metrics against which applicants will be judged to identify and either eliminate or lessen the emphasis given to those that are particularly subject to bias and may also be poor predictors of success (e.g., certain standardized test scores).

___________________

- Decide on the relative weight and priority of different admissions or employment criteria before interviewing candidates or applicants.

- Hold those responsible for admissions and hiring decisions accountable for outcomes at every stage of the application and selection process.

- Educate evaluators to be mindful of the childcare and family leave responsibilities often faced by women, especially when considering “gaps” in a resume.

- When possible, use structured interviews in admission and hiring decisions.

- Educate hiring and admissions officials about biases and strategies to mitigate them.

- Increase stipends and salaries for graduate students, postdocs, nontenure track faculty, and others to ensure all trainees and employees are paid a living wage.

Action 5-C.5 To address issues with retention of women in academic programs and within science, engineering, and medical careers, university and college administrators should:

- Ensure that there is fair and equitable access to resources for all employees and students.

- Take action to broadly and clearly communicate about the institutional resources that are available to students and employees and be transparent about how these resources are allocated.

- Revise policies and resources to reflect the diverse personal life needs of employees and students at different stages of their education and careers and advertise these policies and resources so that all are aware of and can readily access them.

- Create programs and educational opportunities that encourage an inclusive and respectful environment free of sexual harassment, including gender harassment.

- Set and widely share standards of behavior, including sanctions for disrespect, incivility, and harassment. These standards should include a range of disciplinary actions that correspond to the severity and frequency for perpetrators who have violated these standards.

- Create policies that support employees during times when family and personal life demands are heightened—especially for raising young children and caring for elderly parents. For example, stop-the-clock and modified duty policies, which should be available to as wide a group as possible, should be a genuine time-out from work and should not penalize those who take advantage of the policies.

___________________

- Provide private space with appropriate equipment for parents to feed infants and (if needed) to express and store milk.

- Create policies and practices that address workers’ need to balance work and family roles (including not only child and family care but also responsibilities for attending to children’s school and extracurricular activities).

- Limit department meetings and functions to specified working hours that are consistent with family-friendly workplace expectations.

Action 5-D. In order to be effective mentors and to create more effective mentorship relationships, faculty and staff should recognize that identities influence academic and career development and thus are relevant for effective mentorship. As such:

- Institutional leadership should intentionally support mentorship initiatives that recognize, respond to, value, and build on the power of diversity. Leaders should intentionally create cultures of inclusive excellence to improve the quality and relevance of the STEMM enterprise.

- Mentors should learn about and make use of inclusive approaches to mentorship such as listening actively, working toward cultural responsiveness, moving beyond “colorblindness,” intentionally considering how culture-based dynamics can negatively influence mentoring relationships, and reflecting on how their biases and prejudices may affect mentees and mentoring relationships, specifically for mentorship of underrepresented mentees.

- Mentees should reflect on and acknowledge the influence of their identities on their academic and career trajectory and should seek mentorship that is intentional in considering their individual lived experiences.

Action 5-E. Institutional leaders, as well as individual faculty and staff, should support policies, procedures, and other infrastructure that allow mentees to engage in mentoring relationships with multiple individuals within and outside of their home department, program, or institution, such as professional societies, external conferences, learning communities, and online networks, with the ultimate goal of providing more comprehensive mentorship support.

Action 5-F. Colleges and universities should provide direct and visible support for targets of sexual harassment. Presidents, provosts, deans, and department chairs should convey that reporting sexual harassment is an honorable and courageous action. Regardless of a target filing a formal report, academic institutions should provide means of accessing support services (social services, health care, legal, career/professional). They should provide alternative and less formal means of recording information about the experience and reporting the experience if the target is not comfortable filing a formal report. Academic institutions should develop approaches to prevent the target from experiencing or fearing retaliation in academic settings.

Action 5-G. Colleges and universities should create “counterspaces”6 on their campuses that provide a sense of belonging and support for women of color and serve as havens from isolation and microaggressions. Such counterspaces can operate within the context of peer-to-peer relationships; mentoring relationships; national STEMM diversity conferences; campus student groups; and science, engineering, and medical departments. Counterspaces can be physical spaces, as well as conceptual and ideological spaces.

Recommendation 6.

Federal agencies should support efforts and research targeted at addressing different profiles of underrepresentation in particular scientific, engineering, and medical disciplines throughout the educational and career life course.

Implementation Actions

Action 6-A. Given that women are underrepresented in computer science, engineering, and physics as early as the undergraduate level, agencies that support research, training, and education in these fields should incentivize institutions to adopt educational practices that research shows can improve interest and sense of belonging in these fields among women. For instance, the NSF Director should direct the Deputy Directors of the NSF Directorates for Engineering (ENG), Computer and Information Science and Engineering (CISE), and Mathematical and Physical Sciences (MPS) to set aside funding and work collaboratively with the Education and Human Resources Directorate to support education grants that address the following:

- Adoption by college and university faculty and administrators of classroom and lab curricula and pedagogical approaches that research has demonstrated improve interest and sense of belonging in computer science, engineering, and physics among women, such as:

- those that incorporate growth mindset interventions that impress upon students that skills and intelligence are not fixed, but, rather, are increased by learning;

- those that highlight that scientists and engineers are well positioned and equipped to do work that has a positive societal impact; and

- those that highlight the contributions of a diverse array of people to the scientific, engineering, and medical enterprise today and throughout history.

___________________

6 Researchers have defined counterspaces to be: “academic and social safe spaces that allow underrepresented students to: promote their own learning wherein their experiences are validated and viewed as critical knowledge; vent frustrations by sharing stories of isolation, microaggressions, and/or overt discrimination; and challenge deficit notions of people of color (and other marginalized groups) and establish and maintain a positive collegiate racial climate for themselves” (Solórzano et al., 2000; Solórzano and Villalpando, 1998).

- Research and development of new models of curriculum development in engineering, computer science, and physics that take into account the experience level that different students bring to introductory courses and draw upon the lessons learned from successful programs at other institutions (e.g., Harvey Mudd, Dartmouth, Carnegie Mellon).

- Development of new media (e.g., podcasts, videos, television, graphics, and instructional materials (e.g. textbooks, syllabi) that provide students with a diverse array of role models and feature the diversity of individuals whose contributions to science, engineering, and medicine are substantial but may not be as well known by the public. Such an effort could benefit from an interagency collaboration between NSF and the National Endowment for the Arts, which could operate under an existing memorandum of understanding (MOU) between these two agencies.

Action 6-B. Across all science, engineering, and medical disciplines, federal agencies should:

- Address funding disparities for women researchers, particularly for women of color. For example, NIH should address disparities in success rates of Type 1 R01 awards for African American women compared to White women;

- Directly (e.g., through supplements) and indirectly (e.g., through specific programs) support the work-life integration needs of women (and men) in science, engineering, and medicine; and

- In addition to programs designed to support mentorship, support investigation into the impact of sponsorship on the advancement of both White women and women of color into leadership roles in science, engineering, and medicine.

III. PRIORITIZE, RECOGNIZE, REWARD, AND RESOURCE

The recommendations the committee offers here advise institutions, both academic and governmental, to sustainably allocating resources and authority to the leaders of equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts, while providing positive incentives for faculty—in the context of promotions and rewards and recognition by honorific and professional societies—that could pave the way toward culture change yielding broader recognition that the promotion of an inclusive scientific, engineering, and medical enterprise is everyone’s responsibility.

Recommendation 7.

Leaders in academia and scientific societies should put policies and practices in place to prioritize, reward, recognize, and resource equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts appropriately.

Implementation Actions

Action 7-A. University administrators should institutionalize effective policies and practices so that they can sustain transitions in leadership by, for example, writing them into the standing budget and creating permanent diversity, equity, and inclusion-related positions.

Action 7-B. University and college administrators should appropriately compensate and recognize individuals responsible for equity and diversity oversight and equip them with sufficient resources and authority.

Action 7-C. Academic senates of universities should adopt amendments to faculty-review committee criteria that formally recognize, support, and reward efforts toward increasing diversity and creating safe and inclusive research environments. Adopting this criteria sets the expectation that promoting inclusivity is everyone’s responsibility and encourages faculty involvement in university diversity initiatives. Formal recognition of efforts to promote equity, diversity, and inclusion should include consideration of effective mentoring, teaching, and service during hiring decisions, in determining faculty time allocations, and in decisions on advancement in rank, including tenure decisions.

Action 7-D. Professional and honorific societies should:

- Create special awards and honors that recognize individuals who have been leaders in driving positive change toward a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive scientific, engineering, and/or medical workforce;

- Monitor the diversity of nominees and elected members in the society over time; and

- Adopt policies that discourage panels of speakers composed entirely of a single demographic group (e.g., all White men) at meetings.

Recommendation 8.

Federal agencies and private foundations should work collaboratively to recognize and celebrate colleges and universities that are working to improve gender equity.

Implementation Actions

Action 8-A. NIH and NSF should collaborate to develop a recognition program that provides positive incentives to STEMM departments and programs on campuses to make diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts a high priority. Departments and programs would compete to be recognized for their successes in closing the gender gaps in STEMM. Such a program would include multiple rounds: the first to allow departments and programs to develop plans to self-assess their progress and plans

toward the goal; the second to create and implement new programs and practices; and the third to show improvement from the original evaluation. In order for institutions to compete equitably for this recognition, departments and programs that apply should compete against similar institutions. For instance, departments and programs that apply could compete only against others within institutions with the same Carnegie Classification as their own. After the initial exploration of this model by NIH and NSF, other federal agencies could be encouraged to adopt a similar model.

Action 8-B. Federal agencies should provide financial assistance to institutions that would like to be recognized for their efforts to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion. These grants would support the resource-intensive data collection that is required to compete for these awards, which, for example, in the UK often falls to women, and would be granted on a needs-based justification, with priority given to under-resourced universities.

Action 8-C. Private foundations should require that awardee institutions complete a self-evaluation of themselves, specific to the departmental policies, similar to the New York Stem Cell Foundation’s Initiative on Women in Science and Engineering, which required institutions to complete a gender equity report card before receiving funding. In order to continue receiving funding from these private foundations, departments must show improvements, or plans to make improvements, in improving gender equity in their departments.

IV. FILLING KNOWLEDGE GAPS

Although the recommendations offered by the committee speak to the fact that there is much that leaders and employees at academic institutions and in the government can do immediately to promote positive change that is more broadly experienced by women in science, engineering, and medicine, there are critical knowledge gaps that must be filled, with deliberate speed, to support most effectively the improved recruitment, retention, and advancement of all women in science, engineering, and medicine.

Recommendation 9.

Although scholarly research on gender disparities in science, engineering, and medicine has yielded an abundance of information that can be applied toward reaching gender equity, there are critical knowledge gaps remain and require very close attention. These include:

- Intersectional experiences of women of color, women with disabilities, LGBTQIA women, and women of other intersecting identities (e.g., age).

- Strategies and practices that can support the improved recruitment, retention, and advancement of women of color and women of other intersecting identities.

- Factors contributing to the disproportionate benefit accruing to White women of practices adopted to achieve gender equity.

- Specific factors contributing to successes and failures of institutions that have adopted policies and/or implemented programs aimed at diversifying the science, engineering, and medical workforce.

- Long-term evaluation of the promising practices listed in the report, specifically, how their sustained implementation impacts the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women over time.

- Strategies and practices that have proven most effective in supporting STEMM women faculty and students in nonresearch intensive institutions, such as community colleges.

- Characteristics of effective male allies and approaches to training allies.

This page intentionally left blank.