Science and Art Collaborations: Engaging Gulf Communities in Understanding and Addressing Complex Environmental Issues: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (2025)

Chapter: Science and Art Collaborations: Engaging Gulf Communities in Understanding and Addressing Complex Environmental Issues: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

|

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief |

Convened February 19, 2024

Science and Art Collaborations: Engaging Gulf Communities in Understanding and Addressing Complex Environmental Issues

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

BACKGROUND AND WELCOME

On February 19, 2024, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Gulf Research Program (GRP) and the Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences (CPNAS)1 convened a one-day workshop at the 2024 Gulf of Mexico Conference in Tampa, Florida focused on artist and scientist collaborations—and how they could support and inspire a healthy, resilient, and sustainable future across Gulf Coast communities. An ad hoc committee planned a workshop that delved into areas including creative problem-solving, ways to understand and engage with complex topics through creative practices, mutual learning and educational opportunities that result from artists and scientists working together, and how art and science collaborations can elevate community voices.

This activity was designed to combine panels and presentations with a series of interactive activities that encouraged participants to engage with topics throughout the day in both traditional and new ways. In addition to the panel discussions, the workshop employed other creative approaches such as the participation of a graphic illustrator who visually captured key points of the discussion in real time. Furthermore, art supplies on each table encouraged audience members to draw images in response to what they heard or experienced, and a musical performance expressed not only the outcomes from the day but also the spirit of what it means to collaborate and share. These artistic engagement strategies provided an opportunity for workshop participants to experience some of the engagement techniques discussed by panelists and learn more about how they might be used in practice.

Presenters and audience participants were asked three questions to consider and respond to throughout the workshop and were provided opportunities to respond through discussion and written activities throughout the day:

- What role can art and science collaboration play in socio-ecological innovation?

- In what ways is art able to engage broader audiences about complex issues?

- What are some challenges to the Gulf region that the group should address?

ICEBREAKER: STARTING WITH STORYTELLING

Nic Bennett, a performance artist and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Austin whose research focuses on inclusive science communication, opened the workshop by engaging attendees in a “speed storytelling”

__________________

1 For further information on CPNAS see: https://www.cpnas.org/

icebreaker activity that set the tone for the workshop and acclimated participants to the interactive nature of the workshop. During the activity, participants partnered to share 30-second answers to the following questions: “What do you love about the Gulf?” and “What brings you hope?” A sample of the responses that resonated with participants included: there is a critical mass of people in the Gulf who “want to do something to fix the problems;” the next generation is galvanized around issues of climate change and social justice; and art and science working in concert can help these powerful ideas “go everywhere.”

The foundation for discussion throughout the workshop was set by a video provocation provided by Mel Chin, a conceptual visual artist from Houston, Texas, who focuses on multi-disciplinary collaborations and works that “enlist science as an aesthetic component to developing complex ideas.” (See Figure 1.) In response to the three questions posed, Chin shared several examples of his work that engage with complex environmental themes.

In response to the first question, Chin pointed to his pioneering project, Revival Field,2 in which he partnered with Rufus Chaney, a research agronomist at the United States Department of Agriculture, to create a collaborative art/science project that “confirmed the technology of green remediation,” the ability of plants to pull heavy metals from the soil and recycle them. Chin stated that the importance of this project went beyond the site itself, to its creation as a “combination of dreams” between the two collaborators—Chaney’s “to fulfill a lifelong effort to prove that … hyper accumulation in plants was possible” and Chin’s “to sculpt the earth to remediate it using plants as sculptural tools.” Through collaboration, they agreed to “learn each other’s languages,” Chin said, “to seek out the poetics of science and art and apply the pragmatism that each discipline could bring to it.”

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Mel Chin.

To the question about engaging broader audiences, Chin referenced his work for the centennial of the Panama Canal, entitled Sea to See. He aimed to explore the future of the bodies of water on each side of the canal through “a cinematic portrait” of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, capturing their dynamic changes over time. Inspired by the constant flux of these oceans and their interactions, Chin collaborated with scientists to translate complex oceanic data into a video piece. Although the resulting work did not explicitly teach viewers the specifics of the data, it was “compelling enough to make people desire to want to know what the science was saying.”

Contemplating the last question about challenges in the Gulf region, Chin shared his work Revisitation, a painting that reflects his contrasting experiences at Port Bolivar, outside of Galveston, Texas. During his first visit there, he was deeply moved by the natural beauty and splendor of the area. However, in a subsequent experience years later, he was struck by the environmental degradation and pollution that had marred a once beautiful place. In Revisitation, each corner of the painting depicts water in different contexts, including references to oil spills and pollution. The painting is intended to convey Chin’s “anxiety or sorrow about the ecological reality that has befallen this place I loved very much as a child,” he said.

In closing, Chin urged the workshop participants to think not strictly about art or science but “catalytic structures,” a term he uses to signify a transformative way of thinking. “[Art] makes a place for the languages that have not yet formed to exist, to give them space,” he said. The challenge is creating something “that activates the imagination and desire to understand our world deeper, and [subsequently] have enough care and love of it to do something about it.”

__________________

2 Revival Field is an art/science collaboration located in the Pig’s Eye Landfill, a superfund site in St. Paul, Minnesota, with soils contaminated by heavy metals (MelChin.org, n.d.). To help extract heavy metals from the soil, Chin and Chaney planted Thlaspi, a plant with the capacity to extract cadmium and other heavy metals from the soil. The project began in 1991 and continues to the present. To read more about Revival Field: https://melchin.org/oeuvre/revival-field

PANEL 1: BRIDGING THE FIELDS OF ART AND SCIENCE

William (Bill) Fox, director of the Center for Art and Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art, introduced the next panelists, Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry, an artist and architect, respectively, who co-founded the LandArt Generator Initiative (LAGI),3 an initiative that seeks to advance a just and equitable energy transition in response to the climate crisis. To set the stage for the discussion, Fox discussed some of the past work of land artists4 and their relationship to working in the environment. Land artists of the 1960s and 1970s used the land as material, for example. As the art movement evolved, he explained, “land art move[d] from being very ... abstract ... to more about where it’s taking place.” Fox observed that techniques originally developed by land artists have been adopted by other people who wanted to intervene in the landscape to address environmental challenges, with ongoing themes that resonate today—such as sustainability, resilience, adaptation, and regeneration. Artists have an important role to play in the sciences, he noted, because they champion “the data and the information,” infusing it with emotion to effectively communicate it to policymakers.

To start the discussion, Fox invited Monoian and Ferry to introduce their work with LAGI. LAGI projects are aimed to address challenges to the renewable energy transition through artist-led interdisciplinary teams that design the “power plants of the future” to be beautiful places that help people better understand and connect to renewable energy technologies. For Monoian and Ferry, these activities represent a return to an earlier type of power infrastructure, where lack of ability to transmit electricity over long distances meant that power plants were centrally located within cities and designed by artists and architects as part of the fabric of the built environment. They hope that by designing renewable power facilities, they might allow “people to have intimate relationships with the places that power their worlds” and “let loose some of those [imaginative] roadblocks” to cleaner energy.

Their first LAGI competition received 150 submissions from interdisciplinary teams in more than 60 countries; some of those ideas were featured prominently at the World Future Energy Summit in early 2011. “We’ve always been an art project, but suddenly we were bigger than that,” Monoian said. Since that initial call, they have held design competitions for a variety of sites—brownfields, landfills, coastal sites, urban gateway sites, etc.—and now have 1,600 ideas in the competition’s portfolio. If a city wants to work with them, they can look through the portfolio and “see what site typology matches up with their needs.”

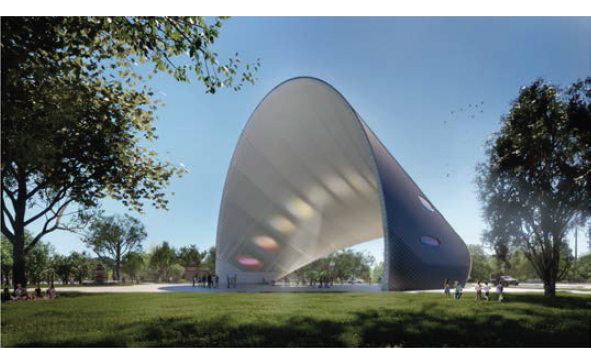

Arch of Time in Houston

The Arch of Time5 is a public artwork by German architect Riccardo Mariano that is currently being constructed in Houston’s Second Ward (see Figure 2). This installation, which will generate solar energy, “engages the public [and] also provides 25,000 square feet of shade in a city undergoing the extreme consequences of global heating,” Ferry said. “There are 11 apertures at the top of the artwork,” shifting the sun’s light in a way that changes every hour, like a sundial. Light that does not go through the apertures is converted into electricity through 60,000

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Riccardo Mariano and the Land Art Generator Initiative.

__________________

3 Land Art Generator is an initiative that “engages the public in the co-design of our clean energy future, bringing together the disciplines of public art, urban planning, creative placemaking, renewable energy, and environmental justice.” Land Art Generator supports some STEAM education projects and a variety of renewable energy projects, most notably their annual open call design competition hosted in a different city each year. (See: https://landartgenerator.org/index.html).

4 Land art is defined as art that is “made directly in the landscape by sculpting the land itself or by making structures in the landscape with natural materials.” See, for example: https://umfa.utah.edu/land-art/about. While people have been producing land art for thousands of years, the land art conceptual movement was popularized in the 1960s and 1970s as an “alternative [method] of artistic production” and a way for artists to “circumvent the commercial art system” (UMFA).

5 The Arch of Time was an entry to the 2019 LAGI competition. The arch is a 100-foot-tall structure composed of photovoltaic cells that generate solar energy. Inspired by the sundial, the Arch of Time’s cylindrical shape is modeled on the sun’s path of motion, with 11 openings oriented in the direction of each solar hour on its surface. A system of louvers allows the sun’s light to shine through the openings into the center of the arch to indicate the time of day (Mariano, n.d.).

solar cells along the south-facing surface. They estimate it will produce about 400 milliwatt hours a year, helping power the neighborhood around it, he explained.

They consider this a regenerative artwork, Ferry said. While there are embodied carbon emissions in all the building materials, they expect the solar energy produced by the artwork will offset that figure and become a “net positive for the climate” around year six, continuing to provide power for 30 years afterwards. They will be tracking the output and plan to celebrate the day the generated power outweighs the embodied emissions.

LAGI requires the submissions to include educational programming suggestions, Monoian said. In Houston, they are putting together a committee with educators and a variety of stakeholders to help them develop curriculum onsite at the Arch of Time as well as related programming. Because funding only allowed for one large project, they are also working on developing a collection of solar murals in communities around Houston, providing an opportunity to work with schools and communities to design their murals focusing on local stories.

Fly Ranch

Fly Ranch6 is an off-grid parcel of land in Nevada owned by the Burning Man Project.7 The owners wanted to treat this land much like Burning Man, “with creativity and collaboration at the core,” Monoian said. Fly Ranch became the site for the 2020 LAGI competition, in which submissions had to consider how to tread lightly upon the site, “respec[ting] and work[ing] with nature,” Ferry said. The winner of that year’s competition designed a project made from local and/or rapidly regenerative materials. The structure includes a learning area, a composting toilet, and a bird habitat. They are building a prototype on-site. This project is “regenerative in a very broad sense of the word,” Ferry said. “It’s not just about creating kilowatt hours or drinking water ... it’s about valuing beyond those things that are very limited.”

Discussion

During the discussion, one participant noted the lack of support for solar panels in Texas because they are not part of the oil and gas industry. She asked how LAGI plans to make use of the Arch of Time as an opportunity to push for people to change that mindset.

Ferry responded that they are aware of difficulties homeowners face with net metered rooftop installations and the antagonistic relationship between utilities and the people who would like to be “prosumers.”8 They hope that the Arch of Time is part of helping to change the conversation. “Conversation leads to political action and hopefully the ‘Arch’ can be... one of many different catalysts to change the situation in Texas.” The arts can be a way to educate about existing opportunities that people may not be aware of, including federal benefits for solar use in the Inflation Reduction Act, he said. “We’re going to use the ‘Arch’ to communicate about those opportunities.”

Another speaker asked what they have learned from challenges of going from the design idea to constructing the project. Monoian responded that initially, the competition was an experiment and could not promise construction of the designs. Now that they have proof of concept, the goal is to focus on building and finding the right partners and funds for the work in the LAGI portfolio.

Ferry framed these projects as an investment for communities rather than a cost, stating “all art gives back.” Monoian went on to identify public art projects’ economic benefits to cities, including the incremental local spending from works like The New York City Waterfalls9 and

__________________

6 Fly Ranch is a 3,800-acre ranch in Northern Nevada owned by the Burning Man Project. Fly Ranch serves as an “open-source land stewardship project, a year-round community and Burning Man space, a place for people to gather, be creative, and innovative, and an oasis for ecology and art.” For more information, see: FlyRanch.BurningMan.org. Additionally, Fly Ranch is a large part of the Burning Man Project’s goal to become carbon negative by 2030. Read more at: https://flyranch.burningman.org

7 Burning Man is “a network of people inspired by [a set of guiding principles] and united in the pursuit of a more creative and connected existence in the world.” Each year, the Burning Man Project creates a temporary city in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert based around community, art, self-expression, and self-reliance. See: Burningman.org

8 “Prosumer” is a portmanteau of the words “producer” and “consumer.” A prosumer is therefore someone who is engaged in both the production and consumption of goods (Cambridge English Dictionary, n.d.). In the context of energy specifically, prosumers are people who both produce and consume the energy they use, often through using renewable power sources like solar and wind (U.S. Department of Energy, 2017).

9 The New York City Waterfalls were a public art installation by Olafur Eliasson on view from June–October 2007 and funded by the Public Art Fund (Public Art Fund, n.d.). The exhibition included four manmade waterfalls located throughout different locations in the city. Eliasson made the waterfalls to encourage viewers to “reconsider their relationships to these spectacular surroundings,” blurring the boundary between urban areas and the natural world (Public Art Fund, n.d.). Read more about the exhibit on the Public Art Fund website: https://www.publicartfund.org/exhibitions/view/the-new-york-city-waterfalls/

Seven Magic Mountains10 outside Las Vegas. “The numbers work out very well for the kind of work that we’re doing.” Although they can’t necessarily power the world with art, they can create exciting designs in important places that engage people and accelerate the deployment of the massive energy infrastructure we need, Ferry said, and “be a counterpoint to the doom and the gloom that sort of paralyzes people to political action.”

PANEL 2: ENGAGING GULF COMMUNITIES TO ADDRESS SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES THROUGH ART AND SCIENCE COLLABORATION

Ghosts of the Gulf

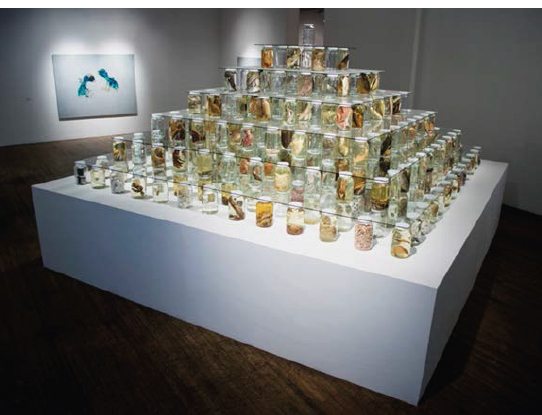

Brandon Ballengée, a biologist and artist, invited a panel to share about their experiences engaging communities in local environmental challenges through art and science collaborations. He began by sharing his own creative projects that he started in response to the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. As a biologist, he focused on studying fish that had been impacted, including 14 “missing” fish species not seen in the Gulf since the spill. As an artist, he made a “sculptural response”—an installation of 26,000 preserved specimens, including some that are oil stained, as a “memorial to the loss of life, [and as a way to] think about what happens when chemicals enter a complex ecosystem like the Gulf of Mexico,” he said (see Figure 3).

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Brandon Ballengée and Various Small Fires, Los Angeles/Dallas/Seoul.

Ballengée highlighted his work, Searching for Ghosts of the Gulf, a Louisiana-based two-year creative placemaking activity in collaboration with Studio in the Woods11 and the Plaquemines Parish government. The goals of this participatory art and science project included looking for the “missing” fish through citizen science programs, an activity that sought to inspire climate adaptation actions, empower community members’ scientific observations, nurture their artistic expression, and share that expression widely (see Figure 4).

The project engaged local communities that are grappling with numerous environmental challenges and socio-ecological stressors, such as some of the fastest rates of land loss globally and the effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the ongoing Taylor Energy oil spill. According to Ballengée, the people of Plaquemines Parish “are suffering some of the same consequences as the fishes.” In considering how they could work with the community to better understand and engage with the complex challenges they are facing, “we came up with the idea of playing with dead fish,” Ballengée shared. Community

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Brandon Ballengée and Various Small Fires, Los Angeles/Dallas/Seoul.

__________________

10 Seven Magic Mountains is an art exhibit by Ugo Rondinone in the desert 10 miles south of Las Vegas. The exhibit is comprised of seven 30–to 35-foot-high cairns or “mountains” made from colorfully painted locally sourced boulders. The exhibit, which has been in place since 2016, is “physically and symbolically mid-way between the natural and the artificial, once again prompting audiences to question the boundaries between the natural and built environment.” For more information, see: SevenMagicMountains.com

11 A Studio in the Woods is an artistic and academic residency program run out of Tulane University’s ByWater Institute whose mission is to “foster creative responses to the challenges of our time by providing retreats to artists, scholars, and the public in [a] protected forest on the Mississippi River” For more info, see: AStudioInTheWoods.org. In addition to offering residencies, A Studio in the Woods also conducts programs around forest restoration and research and community outreach.

members were invited to fish drawing workshops where they drew preserved specimens and discussed how fish in the Gulf are adapting to various pressures. The discussion on fish adaptations provided a way to talk about environmental and social stressors and explore how the community can foster “positive changes in our society and [the] ecosystems around [them].”

Ballengée facilitates these workshops with students and faculty at schools, YMCAs, marinas, parks, and other places, including the Royal D. Suttkus Fish Collection at Tulane University, the largest preserved fish collection in the world. Ballengée and a team of engaged community members also started a festival called Fishstock, which billed itself as a celebration of Plaquemines’ rich natural resources and culture. There were fish-drawing workshops alongside other hands-on activities and musical entertainment, he said, and more than 400 people attended. Over the course of two years, this activity included 54 events and reached more than 2,500 people, including a third of the total children in the parish. They exhibited drawings through pop-up exhibitions and a coloring book, which was distributed to Plaquemines schools. On the science side, they discovered some of the missing species, he said, including one during a fish drawing workshop.

Resilience in Broward County: Underwater HOA

Jennifer Jurado, chief resilience officer for Broward County, Florida, shared the beginnings of a new collaboration with artist Xavier Cortada, a Miami-based artist who uses socially engaging art to support community-led climate conversations. Jurado explained that the county has complex climate-related challenges and is already facing severe economic and public health issues resulting from the impacts of intense rainfall, severe heat, storm surge, and degradation of coral reefs.

Jurado highlighted that Broward County is engaged in resilience efforts, including developing climate action plans, regional plans, and sea level rise projections in collaboration with four southeastern Florida counties. Her office is developing a community-wide assessment and resilience plan.12

Despite involving diverse stakeholders, discussions have remained predominantly government focused. Even with various outreach efforts, including dashboards and different channels to share this work, many people prefer to receive their information from non-governmental sources, she said. Broward County also engages students through regional climate summits, inviting them to participate as keynote speakers and join in listening sessions. However, participating students say they are the only ones in their schools discussing these issues. This is particularly disheartening, Jurado noted, because her office and others gain so much substance and thoughtfulness from their conversations with students.

Xavier Cortada is bringing his experience working with communities on resilience issues to the collaboration in Broward County. For example, in Miami-Dade County, he created the Underwater Homeowners’ Association (UHOA13) project. In this initiative, Cortada works with community members to research sea-level rise and elevation where they work and live. Participants create art reflecting this research, such as yard signs displaying the number of feet their home or workplace is above sea

SOURCE: Photo and caption courtesy of the Xavier Cortada Foundation.

__________________

12 Broward County is developing an official county-wide resilience plan that includes improvements in a variety of areas to adjust to changing environmental conditions in the next 50 years. This plan includes infrastructure improvements and other physical redevelopment strategies, but it also places a significant emphasis on community engagement and advancing resilience priorities identified by Broward County residents (Broward County, 2023). Read more about the planning efforts on Broward County’s website at: https://www.broward.org/ResiliencePlan/Pages/default.aspx

13 Read more about the Underwater HOA project on Xavier Cortada’s website: https://cortada.com/art2018/underwaterhoa/

level (see Figure 5). The art serves as a “visible, constant reminder that connects you to the landscape and the exposures,” Jurado explained (see Figure 6).

In Broward County, Cortada will initially work with 10 high schools to create murals, invite students to create their own elevation yard signs, and host climate ambassador workshops. Cortada and the students will also create a tile mural with underwater imagery in a parking garage in downtown Fort Lauderdale, near an intersection that experiences extreme flooding during storm surge events.

Broward County is just getting started with this collaboration, Jurado said, but they are hopeful that it can be a demonstration of the “power of a new communicator supporting [their work].” The office of community resilience’s partnership with Cortada has precipitated an additional partnership with the cultural affairs division and the Community Foundation of Broward. Jurado hopes this initiative leads to new, sustained partnerships.

During the Q&A, an audience member noted it was relatively rare for governments to reach out to artists and asked Jurado how the partnership with Cortada came to be and what challenges they have encountered. Jurado noted Cortada was already working with Miami-Dade County, so he had familiarity with local governments.

SOURCE: Photo and caption courtesy of the Xavier Cortada Foundation.

Broward County has a strong record of investing money for the arts in capital projects, she added. Flexibility on both sides is important, Jurado explained. Their plans for crosswalk art and utility box wraps ran into permitting issues, so they shifted to art installations at schools instead.

Flow Tuscaloosa

Jamey Grimes, assistant professor of art, sculpture, and museum studies at the University of Alabama, introduced his project, Flow Tuscaloosa,14 an art and science collaboration that began with a faculty fellowship at the University of Alabama’s Collaborative Arts Research Initiative (CARI),15 a program that is intended to enhance creative collaborations in academia. Grimes partnered with another CARI fellow from the history department to create the Flow Tuscaloosa project as “an outdoor light celebration of ecology and history,” featuring local waterways and light-based sculptures. By collaborating and combining resources, they were able to secure funding and expand the project to include public educational workshops, a series of art exhibitions, and a walking lantern

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Jamey Grimes.

__________________

14 Flow Tuscaloosa is an art-science collaboration that began in 2022 between faculty at the University of Alabama and the Selvage Collective, a curatorial collective focused on showing different sides of historical events, as an attempt to “inspire protection of the Black Warrior River and its tributaries and to bring attention to the unique history and ecology of [Tuscaloosa’s] watershed” (FlowTuscaloosa.com, n.d.). Programming includes artist exhibitions, park cleanups, lantern making workshops, and subsequent lantern parades at Hurricane Creek (FlowTuscaloosa.com, n.d.). Programming is aimed at Tuscaloosa community members, with a special focus on youth.

15 CARI is an interdisciplinary, arts-focused research engine driven by the interests of faculty across the university. CARI offers a 2-year fellowship for faculty at the University of Alabama to develop new interdisciplinary work and increase the impact of their work (CARI, n.d.). Additionally, CARI co-sponsors the Collaborative Arts and Museums Program, which encourages public engagement with art through University of Alabama Museums. For more information, see: https://cari.ua.edu/

parade along Tuscaloosa’s Riverwalk that turned into a celebration for the community (see Figures 7 and 8).

Grimes discussed some of the opportunities that emerged with the project as well as some of the lessons they learned in the initial phases. Since these activities fundamentally required active engagement with the public, Grimes explained, they also required significant collaboration with other diverse partners (including local and state art councils). While combining resources with community partners made difficult tasks much easier, it also caused the project scope to grow significantly. An important consideration became not to overburden contributors but to understand and respect their motivations and limitations. “The goal was that everyone who helped would want to return for more, rather than getting burned out,” Grimes shared.

Ultimately, the team hosted 25 community workshops in which residents learned about the history of human interactions with local waterways and the diverse flora and fauna inhabiting them. Regional experts shared their personal connections to the waterways, and participants crafted their own unique lanterns. Throughout these events, the team aimed to encourage diverse audiences to mingle, Grimes said. “When I typically share my art in a museum or gallery, it’s all about me. As this project grew and grew, it became something bigger than what I was used to doing with art. It was more rewarding, more powerful, and more effective,” he shared. He viewed each workshop and parade participant as a collaborator.

In the second run of Flow Tuscaloosa in the spring of 2024, Grimes’ team included an amphibian exhibit that he had been working on independently. They also held fewer workshops for longer periods, providing more extensive education, as the original experience felt rushed. He noted that their 2022 experience enabled them to apply more confidently for grants and explain the project to new partners.

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Jamey Grimes.

Grimes shared that working with students has taught him the importance of investing energy in youth education and the need to adjust adult expectations and measures of success. He noted that “the stubborn world of adults” is using outdated measures of success that do not take environmental well-being into consideration, and welcoming the youth into the discussion can help us move past this. These larger community-based projects are also starting to “transform what [he] see[s] as legitimate research,” Grimes said, leading him to question traditional measures of success, and noting the distinction between academic research and community engagement and service.

Creative Forces

Art therapist Heather Spooner spoke about her work with Creative Forces,16 an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with the U.S. Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs. This program supports the health, well-being, and quality of life for military service members, their families, and their communities, particularly in relation to trauma and traumatic brain injury. The network includes art, music, and dance movement therapists, as well as artists from various disciplines, policymakers, and increasingly, researchers.

Spooner noted that creative arts therapies are unique because many patients want to continue receiving therapy. However, once treatment goals are met, arts therapists often encourage patients to engage with their communities, potentially through community arts partners. One of her favorite examples of multi-directional work involved a former army officer who wanted to share her story through quilting. While Spooner could teach the offi-

__________________

16 There are three main components of the Creative Forces program: clinical programming, community programming, and research. Clinical art therapists are mental health professionals embedded in treatment teams and addressing individual treatment goals in Veterans Affairs and military hospitals around the country. Community programming involves community arts organizations working with service members and veterans in multi-directional ways. Sometimes people may not need to work with a therapist but could use the quality of life or health benefits that come from arts engagement, she added.

SOURCE: Photos courtesy of Heather Spooner.

cer how to express herself through metaphor, color, and composition, Spooner did not know how to teach quilting. The former Army officer found a community quilt group to work with, and she alternated between Spooner and the quilt group to develop her art (see Figure 9).

Spooner highlighted that research is becoming a significant part of Creative Forces, involving partnerships with researchers, clinicians, and neuropsychologists. Approximately 20 of their therapists across the country publish peer-review articles and conduct small-scale research studies with other therapists. Recently, they completed four larger pilot projects: two on art therapy and emotional processing, and two on music therapy and chronic pain. Spooner meets weekly with an interdisciplinary group, including statisticians and neuropsychologists, to determine how to demonstrate the impact of art therapy work, including the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain imaging. This scientific research provides an evidence-base for the art-based interventions employed by Spooner and others at Creative Forces.

One of the Veteran’s Affairs lesser-known missions is disaster readiness and response, Spooner concluded, and the Creative Forces initiative is exploring whether some of what they have learned about trauma and resilience could apply to disaster response, including chronic long-term disasters. They are conducting an initial exploration through the Uvalde Love Project,17 including mural work at the site of the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde, Texas.

Discussion

A workshop participant asked the panel whether they had experience programming for younger audiences, including nonverbal participants and/or those on the autism spectrum. Ballengée highlighted his fish project, emphasizing its tactile nature. He recommended incorporating tactile or sensory elements and providing quiet spaces as being beneficial for learners on the autism spectrum. Spooner added, “The arts in general are very good for reaching people who are nonverbal,” suggesting music, movement, drama, or integrating arts into various ways of learning.

Another audience member asked how the panelists’ evaluated and measured their projects, especially if donors were involved. Grimes responded by detailing how Flow Tuscaloosa enlisted a survey evaluation expert. Early survey questions focused on attendance to multiple events and how people were making connections. This year, his team is refining evaluations to directly address the art, seeking measurable outcomes in the created works. For instance, if students depict elements representing the life cycle of a frog or incorporate something they learned about the environment into their art, these are aspects they can evaluate, Grimes explained.

An audience member asked about the reproducibility of the projects discussed and whether any project had an accessible implementation tool kit. Ballengée shared that two students, who double-majored in art and biology, worked with him on Ghosts of the Gulf and learned to be teachers themselves when he provided them with a template, which he encouraged them to modify. They also distributed written resources to interested faculty and teachers and brought specimens to those interested. Jurado mentioned that artist Xavier Cortada’s website has extensive information about the “Underwater HOA,” including a document demonstrating his approach. Spooner noted that in Creative Forces’ research, there is tension between the pressure to conduct randomized controlled trials and the inherent creativity of art therapy. Her group is exploring ways to document the process so others can follow it without stifling creativity.

__________________

17 The Uvalde Love Project is a mosaic art project led by Wanda Montemayor intended to help the survivors of the 2022 Robb Elementary School shooting heal and bring hope to their community (UvaldeLove.com, n.d.). The project was led by a team of art therapists who also met with teachers, tutors, and city personnel to provide “trauma specific training and hands-on workshops” To learn more about the project, see the Uvalde Love Project Website see: https://www.uvaldelove.com/project

Another question focused on the “ingredients” for successful collaboration. Ballengée emphasized the importance of learning to listen, which he found surprisingly challenging. He noted that young community members possessed significant knowledge about their environment, and listening to them helped his team develop ideas about adaptation. Jurado agreed, recalling how early in her work, other agencies often offered standard solutions regardless of the constituents’ stated need. “We’ve tried really hard to have those listening sessions and hear what’s important to the community,” she said, recognizing that everyone has different, valid motivators. She also suggested giving credit to others and not needing to be perceived as the source of the “right” answer.

Grimes added that while overburdening collaborators may get work done, “if you use people that way, you’ve lost a long-term asset.” He also mentioned that it is easy to become overwhelmed and lose sight of the purpose of collaboration if there is no intent to move from the theoretical to actualization and implementation.

In his final thoughts, Ballengée noted that one reason art complements science is that art allows people to experience scientific concepts on another level, making science more accessible to a broader audience outside the scientific community.

PANEL 3: STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY

Artistic Intervention: Fred Johnson

In planning the workshop, the organizing committee requested an artistic intervention to provide participants with (1) a creative disruption to engage them in a new experience beyond the typical workshop format and (2) an exploration of the possibilities of engaging with art, music, and storytelling to inspire more meaningful discussions of complex topics. Fred Johnson, musician and artist in residence and community engagement specialist at The Straz Center for the Performing Arts,18 provided a performance in which he played two instruments, a Kordafone (a stringed instrument that he made himself) and a laptop Cajon (a percussion instrument) (see Figure 10). Johnson improvised a song on the spot that summarized the workshop thus far and reflected his response to the workshop’s themes and discussions. Throughout his performance, the audience clapped and responded to Johnson’s cues in seeming delight and appreciation of his novel approach to summarizing the first half of the day.

SOURCE: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Gulf Research Program event recording.

There are many ways to blend art and science, but when “all is said and done, it’s how we choose to be with each other,” Johnson sang. “You can have a conversation all day long, but if it just stays in your head, if you don’t feel it in your heart, then the chance of change is small.”

The Gulf is always going to be there, but we won’t; he sang: “But what will we feel in our last breath; will we feel that we did all that we should to make a change?” Creating that change happens every day, by thinking about how we are going to be with each other. “The challenges we face, we face them together.”

“The greatest distance is between the heart and mind,” Johnson concluded, though art can function as a bridge to close this gap. “Art moves us into the feeling place and moves us into the opportunity to recognize what we do matters.”

Minorities in Shark Science

The day’s final panel began with a short film from Jasmin Graham on Myrtle Beach’s Black fishing community and their connection to ocean conservation. Graham, a marine biologist and president of Minorities in Shark Science, is a member of this community. Her family has lived in Myrtle Beach, “for as long as we can remember,” she said, descending from enslaved people in the Gullah Geechee culture.

__________________

18 The Straz Center for Performing Arts is a nonprofit organization based in Tampa, Florida, with a mission to “inspire, educate and connect our community through the power of shared performing arts experiences” (Straz Center, n.d.). In addition to showing traditional theater and dance performances, the Straz Center also makes community engagement a top priority, offering programming around arts education, arts and the military, arts and health, and more. Read more on the Straz Center’s website: https://www.strazcenter.org/

Graham grew up connected to the water through her father’s fishing. However, as she began her marine biology career, she noticed that conversations around ocean conservation often excluded fishers, who were frequently blamed for various environmental issues. She expressed that she found it confusing to hear how her community could be considered “the problem,” saying, “Do you know that in my community, all of the fish that are caught, the first thing they do is give it to elders who can’t leave their homes to go get food?” She emphasized that the Myrtle Beach fishing community understands that their primary food source is from the ocean, so the last thing they want to do is harm it.

Graham shared that the community is often frustrated by approaches to ocean management and shoreline decision-making. When fishers are told they cannot catch certain fish and are cut off from the water because of privatization of beach access, “what they see is just more of the same oppression that they have been subjected to for generations and generations and generations.” She highlighted that those most impacted make sacrifices and are often not included in decision-making processes. Fishers have told her that “rich White people get to decide what happens” while the fish and Black fishing community suffer the consequences. Despite having first-hand knowledge about the effects of beach renourishment on fish, their insights are disregarded. Graham uses digital storytelling to amplify the voices of those not typically heard in these decisions.

Bayou Culture Collaborative

Maida Owens, Folklife Program Director at the Louisiana Division of the Arts, discussed her involvement with the Bayou Culture Collaborative,19 which has two missions: to sustain traditional cultures and artisans and to bring together people who care about these issues. Owens shared several initiatives, such as the micro-grants program, “Passing it On,” which pays master artisans to pass on traditions within their communities (see Figure 11). Additionally, with the help and vision of her colleague Shana Walton at Nicholls State University, the collaborative hosts online gatherings about Bayou culture. Initially aimed at introducing these issues to the larger arts network, the conversation has since broadened to include people in science and environmental groups. “Basically, we’re sharing stories; we’re helping people connect,” she said.

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Gene Hebert and the Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program.

Owens emphasized that discussions about community resilience must include both the physical environment and people and their cultures. The initial online gathering of the Collaborative was a success; participants began creating working groups, and she now receives calls from state agencies about various plans. The state chief resilience officer “follows us closely,” she said, noting that the Collaborative influenced his first statewide resilience report.

Owens acknowledged that much work remains, explaining that much of south Louisiana is in “active collapse,” with some of the highest land loss in the world and many residents not returning after hurricanes. At every Collaborative gathering, it is reiterated that they “do not have the answer[s],” but together they can “explore issues and options.” Owens highlighted the importance of culture sharing, stating “culture provides a sense of well-being and helps people connect.” In Louisiana, culture is celebrated and is a “dominant force for social cohesion.” As the state starts to depopulate, she is concerned that people will become disconnected from local culture. “If you don’t take care of [culture], it can be lost in a generation,” she concluded.

__________________

19 Read more about the Bayou Culture Collaborative on the Louisiana Folklore Society’s website: https://www.louisianafolklore.org/?page_id=1215

Discussion

Henry G. Sanchez, founder and director BioArt Bayou-torium,20 asked the panel if these kinds of conversations could be maintained given that some state governments around the Gulf are not necessarily sympathetic to some of these voices.

In response, Graham said that “we can’t be bullied into not talking about [these issues].” She explained that one reason she left academia was to have the freedom to speak openly. Running her own non-profit allows her to do this. However, she emphasized that funding agencies need to “back people up,” especially when their work is attacked. “You can’t fund something and then say ‘but also if you get sued, you’re on your own,’” she said. Graham criticized funders for retracting their outspoken support for certain projects and grantees when their work was no longer politically supported. She urged those with even a small amount of influence to speak out.

Fred Johnson responded that it is really a question about how we choose to be with one other. As an arts institution, the Straz Center aims to “give a voice to the voiceless,” including through their arts and health initiative. “One of our big goals is to help people regain their sense of humanity,” he said, especially in a politically divisive climate. “Storytelling is really important,” Johnson added. He has witnessed many situations in which people were at odds, but hearing each other’s stories shifted the conversation in a positive direction.

Owens noted that conversations among and between state agencies are very different than those between any state agency and a constituent. “The anger [toward agencies] is justified, and very appropriate in many situations,” she said. However, they have chosen to approach agencies by asking, “How can we help you?” Communicating on an interpersonal level and remaining relatively out of the public eye has helped them achieve their goals.

Sanchez asked whether greater involvement within the formal economy, specifically participation in the petrochemical sector, should carry a negative implication for artists and scientists. Graham responded that Sanchez’s question indicates a tendency to assign blame individually rather than address systemic issues. She pointed out that entire groups of people depend on such industries to live. Blaming them is misguided, just as blaming a neighbor who is not recycling rather than the company creating the plastic.

Nic Bennett recalled an exercise they do in theater work called “Where Did You Get Those Shoes,” in which the group tries to trace back all the elements that made a participant’s shoes. This exercise reveals how “lives are entangled with the making of our shoes and the materials all over the world,” they said. Even if much of that information is hidden or unknown to us, “we start to see the systems; we start to see how it’s messy.”

In ocean conservation, the question often arises about whether to work with people in industries contributing to climate change, said Ombretta Agró Andruff, executive director of the ARTSail Residency and Research Initiative.21 To her, it is essential to have all stakeholders at the table. In a recent effort to bring together women who are impacting ocean conservation, she invited someone who works in the plastic industry. She has received significant pushback over this, but she thinks that it is important to understand the conversations and innovations in those industries.

A participant from the audience shared her experience working as a scientific illustrator in the defense industry, saying it taught her that she could argue for and support change within that industry. “I was able to give them another perspective,” she said.

In final takeaways from the panel, Agró Andruff expressed hope that those listening had started thinking more about collaborations and how to engage people where they are. Owens emphasized the importance of the art and science conversation, stating “Art will reach people who will never read a report or study a graph—it’s really a means to broaden the audience.”

__________________

20 The BioArt Bayou-torium is a “socially engaged, bio-art based project invites the general public to make art by investigating nature through the aid of science tools and provides bilingual pontoon boat tours of the nature and history of the Bayou” (bioartbayoutorium.org, n.d.). The exhibit, originally based in a shipment container in Houston, Texas, has now expanded to offering activities throughout Houston’s Buffalo Bayou, including pontoon boat tours of the landscape. Read more at: https://www.bioartbayoutorium.org/

21 ARTSail is an artist residency program that “fosters collaborations between cultural creators and climate experts to address South Florida’s climate crisis” (Artsail.info, 2020). In addition to offering residencies, ARTSail also hosts exhibitions, engages in community outreach, builds awareness of climate issues, and uses art to engage in political advocacy (Artsail.info, 2020). To learn more, see: https://www.artsail.info/about

FINAL THOUGHTS & NEXT STEPS

As a wrap-up to the workshop, J.D. Talasek, director of CPNAS, asked participants to share a one-phrase or sentence takeaway from the workshop, as well as their next steps to move forward.

Participants’ takeaways included: “art bridges barriers,” “community is power,” “consider who benefits from your silence or shame,” and “the importance of listening to everyone.” One participant was particularly struck by collaborations that engaged children. In this participant’s work with students in St. Petersburg’s elementary schools, she noted that the kids are deeply interested in and concerned about the state of the environment, and engaging children often means parents will learn too. Participants also had the opportunity to reflect on the day’s guiding questions and take a moment to write down any final responses on sticky notes that were collected by workshop staff. Samples of the most resonant responses are in Table 1 below.

As next steps, one participant said they would continue to create art with their friends but redirect their focus toward “what we can do.” Another participant stressed the importance of making new connections and fostering those relationships, while another wanted to bring these kinds of conversations “out of the convention centers.”

TABLE 1

Compiled Engagement Questions and Responses

| QUESTION | RESPONSES |

|---|---|

| What role can art and science collaboration play in socio-ecological innovation? |

Innovate biologically inspired designs We need diversity of thought to address complex unsolved problems facing us regarding climate and the ecological crisis Science asks questions to seek answers while art points out the questions we did not even see |

| In what ways is art able to engage broader audiences about complex issues? |

For a community that is visited by tourists, [art] can make our value and love for the environment visible. Make something compelling enough to dare people to want to know more Art helps present big topics in different or kinesthetic ways Artists translate knowledge for others to understand Artists can reach people who will never read a report or study a graph |

| What are some challenges to the Gulf region that the group should address? |

Empower youth, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, and community voices Activate changemakers Work to engage local communities more We need industrial level solutions to pollution and environmental protection Address issues of water quality and human waste |

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Taylor Kate Brown and Sasha Allison as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the author or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants; the planning committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

PLANNING COMMITTEE William Fox (Chair), Nevada Museum of Art; Ombretta Agro’ Andruff, ARTSail Residency and Research Initiative; Brandon Ballengée, Atelier de la Nature; Samantha Joye, University of Georgia; Nancy Knowlton, Smithsonian Institution; Henry Sanchez, BioArt Bayou-torium

STAFF Lauren Alexander Augustine, Executive Director; Sasha Allison, Research Associate; Dan Burger, Program Director; Sherrie Forrest, Program Director; Laila Reimanis, Associate Program Officer; Juan Sandoval, Senior Program Assistant and Research Assistant

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Francisco De Caso, University of Miami; Jody Deming, University of Washington; William Fox, Nevada Museum of Art; and Weston Twardowski, Rice University. Marilyn Baker, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS This workshop was supported by the Gulf Research Program.

For more information, visit https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/art-science-collaborations-for-healthy-and-resilient-gulf-of-mexico-communities-a-workshop

SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2025. Science and Art Collaborations: Engaging Gulf Communities in Understanding and Addressing Complex Environmental Issues: Proceedings of a Workshop in—Brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/29062.

|

Gulf Research Program Copyright 2025 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. |

|