Regional Disaster Response Coordination to Support Health Outcomes: Community Planning and Engagement: Workshop in Brief (2014)

Chapter: Regional Disaster Response Coordination to Support Health Outcomes: Community Planning and Engagement - Workshop in Brief

|

WORKSHOP IN BRIEF |

INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE Advising the nation • Improving health |

Regional Disaster Response Coordination to Support Health Outcomes: Community Planning and Engagement—Workshop in Brief

When disaster strikes, it rarely impacts just one jurisdiction. Many catastrophic disaster plans include provisions of support from neighboring jurisdictions that likely will not be available in a regional disaster. Bringing multiple groups and sectors together that don’t routinely work with each other can augment a response to a disaster but can also be extremely difficult because of the multi-disciplinary communication and coordination needed to ensure effective medical and public health response. As many communities within a region will have similar vulnerabilities, it is important to establish responsibilities and capacities and be able to work toward common goals to address all-hazards when the entire region is impacted.

“Community planning and engagement is a domain that has been lagging significantly behind in meeting the preparedness challenge,” stated W. Craig Vanderwagen, workshop chair.

The Institute of Medicine’s Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events is organizing three “regional” workshops in 2014 to explore opportunities to strengthen the regional coordination required to ensure effective medical and public health response to a large-scale multi-jurisdictional disaster. For the purposes of these workshops, “region” is defined as a multi-county or multi-state affected area, not necessarily abiding by the regions defined by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Each regional workshop will include discussion of mechanisms to strengthen coordination between multiple jurisdictions in various regions to ensure fair and equitable treatment of communities from all impacted areas.

In March 2014, the Forum convened the first regional workshop bringing together key stakeholders to examine community planning and engagement when planning for health incidents in a large-scale response. Two additional workshops focusing on ensuring health outcomes in a regional disaster will explore issues of incident and information management and surge management in July and November 2014, respectively. A full summary of the entire workshop series will be available in spring 2015. This brief summary highlights the discussions that emerged from the presentations and discussions at the workshop. These conversations represent the viewpoints of the speakers and should not be seen as the recommendations or conclusions of the workshop, but they provide a valuable snapshot of the current state of community planning and engagement for regional preparedness initiatives and potential paths forward.

The National Health Security Preparedness Index defines community planning and engagement as “coordination across the whole of community—organizations, partners, and stakeholders—to plan and prepare for health incidents, and to respond to and recover from such incidents with the goal of ensuring community resiliency, well-being, and community health.”1 To focus in on fundamental pieces of community planning, discussions were held on cross-sector collaboration, at-risk populations, management of volunteers during emergencies, and social capital and cohesion.

“At the bottom line is engagement and empowerment to increase the survivability for individuals and populations.” —W. Craig Vanderwagen

1 http://www.nhspi.org/content/domain-community-planning-engagement

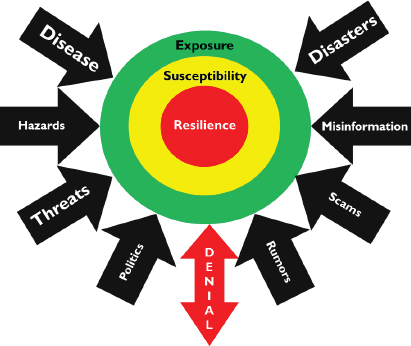

FIGURE 1 Planning beyond “resilience” frameworks for cross-sector collaboration.

SOURCE: Jones presentation, March 26, 2014.

Cross-Sector Collaboration

“If you start looking at the ‘why’ every time you go into a collaboration, you’ll actually have better conversations with people because it matters if you’re collaborating for the same reasons and for the same outcomes.”

—Ana-Marie Jones

Despite great effort, traditional disaster response agencies are often unable to address all of the emergency preparedness, planning, and response needs of increasingly diverse communities. The concept of “collaboration” remains largely misunderstood by key stakeholders, stated Ana-Marie Jones, Executive Director of Collaborating Agencies Responding to Disasters. Most of the struggles and failures around collaboration stem from unrealistic expectations and a lack of understanding of the component pieces involved. In pursuit of more and higher-quality cross-sector collaboration in disaster planning, Jones and individual participants explored how to expand collaborative efforts, as well as the changes in focus and organization that would promote this.

According to Jones, the concept of “collaboration” has long been assumed, expected, advocated, romanticized, and scapegoated in the face of failure although it is not very well understood. Various participants stated that cross-sector collaboration is not an easy task and that it depends first on understanding an organization’s partners, then making commitments, communicating, and coordinating.

- Plan beyond resilience, Jones said. Recently, the focus of emergency managers has been resilience; however, the field should look beyond communities just “bouncing back” from a disaster, she noted. Limiting a region’s potential exposure to an incident and working within and across communities to make them less susceptible to a disaster are two preventative layers that are important to consider with cross-sector collaboration (see Figure 1).

- Ensure coordination of the mission among partners, was a point emphasized by John Hick, Associate Medical Director for EMS at Hennepin County Medical Center. Consideration of all partners across a region and understanding of similarities and differences in regulations and operations in different environments can help define each partner’s role in the region and garner support from participants.

- Decrease reliance on intangibles, Jones noted. Given the staffing and financial constraints that can negatively affect the sustainability of partnerships across a region, a few participants opined that it is important to build systems that are independent of individuals to memorialize buy-in from provider organizations and maintain continuity.

- Balance the needs of each community, Vanderwagen reiterated. Jones and several participants said that including diverse perspectives within and between urban, rural, and frontier settings is essential for successful day-to-day partnerships and the operation of the incident management structure with multiple jurisdictions involved.

At-Risk Populations

“We need partnerships. Having a key person with the Division of Emergency Management has made just a critical difference in support throughout the state and all of the counties, having county emergency managers on board and tribal emergency managers.” —Teresa Ehnert

Teresa Ehnert, Bureau Chief of Public Health Emergency Preparedness of the Arizona Department of Health Services, discussed considerations for at-risk populations2 (see Figure 2) in regional disaster preparedness and planning, using strides made in Arizona as an example. In 2010, Arizona developed a strategic framework to prepare public health systems for all-hazards responses with one major goal being to sustain and develop programs for at-risk population preparedness. Within this priority, she said, planners created four strategic objectives:

- Strengthen preparedness planning with access and functional needs stakeholders

- Integrate behavioral health, public health, and health care system response capabilities

- Engage and establish partnerships with non-English-speaking/limited-English-proficiency stakeholders

- Implement strategies for communicating with geographically isolated populations

To achieve its strategic objectives, Ehnert explained that Arizona found it essential to forge community partnerships, especially between emergency management and disability groups, observing the mantra “nothing about us, without us.”

During these conversations, individual participants highlighted important discussion topics for improving regional disaster preparedness and planning for at-risk populations:

Arizona’s new goal is to ensure equality by integrating the planning for people with access and functional needs (physical, sensory, cognitive, and medical) with the general population, explained Ehnert. Under this approach, all shelters across the state have become completely accessible for people with specific needs, and Arizona no longer sponsors special health care or medical needs shelters.

- Communities that can define and understand the needs of their at-risk populations are better prepared, Ehnert noted. Connecting emergency planners with “whole of community” organizations and individuals that serve or represent at-risk populations can create comprehensive regional planning inclusive of at-risk populations.

- Facilitation of regional information sharing regarding at-risk individuals could be done by enhancing mechanisms for sharing information across entities in the same region, shared Suzet McKinney, Deputy Commissioner at the Chicago Department of Public Health. Identification of at-risk populations is often challenging, and shared information from the health care system across state or county lines could help better prepare the distribution of regional assets and capabilities.

2 “Before, during, and after an incident, members of at-risk populations may have additional needs in one or more of the following functional areas: communication, medical care, maintaining independence, supervision, and transportation. In addition to those individuals specifically recognized as at-risk in the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act (i.e., children, senior citizens, and pregnant women), individuals who may need additional response assistance include those who have disabilities, live in institutionalized settings, are from diverse cultures, have limited English proficiency or are non-English speaking, are transportation disadvantaged, have chronic medical disorders, and have pharmacological dependency” (HHS, 2012) https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Pages/at-risk.aspx.

FIGURE 2 Examples of at-risk populations that may require extra planning considerations in a disaster.

SOURCE: (a) Ehnert presentation, March 26, 2014; (b) Andrea Booher/FEMA photo, August 17, 2010; (c) FEMA photo, September 15, 1995.

Management of Volunteers During Emergencies

“Being able to have volunteers within your pool that come from all these cross-sector areas, to bridge some of those gaps, helps with coexistence, the communication, and ultimately the collaboration in a regional response.” —Captain Robert Tosatto

There are common misperceptions about volunteers from the viewpoint of emergency managers, noted Captain Robert Tosatto, Director of the Division of Civilian Volunteer Medical Reserve Corps. Although they may be perceived as unskilled, undisciplined, and unprofessional, the truth is that volunteers can often bring subject matter expertise that is not otherwise accessible. Another common misconception is that volunteers are free. There are always costs associated with volunteer coordination, training, supplies, and equipment. Having a large pool of volunteers to access during a disaster is important, explained Tosatto, but so is having good volunteer management practices in place to increase volunteer comfort level and improve their overall preparedness and skills in a disaster setting. Having volunteer networks able to operate at a grassroots community level is a strength but also a weakness, he said, because each unit across a geographic area may have different methods or protocols in their operations.

Tosatto explained that there are three types of volunteers:

- Generic (no license or certification needed) versus skill-based (e.g., emergency medical technician)

- Planned versus spontaneous

- Affiliated (e.g., Medical Reserve Corps) versus unaffiliated

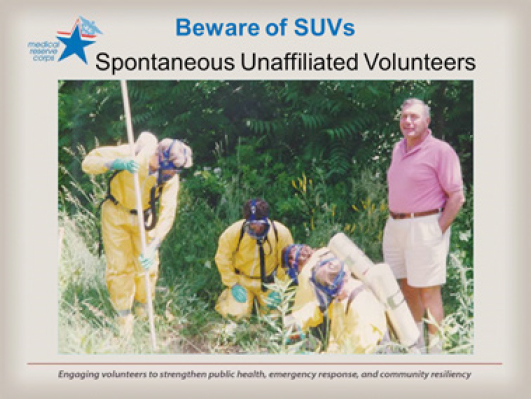

FIGURE 3 Spontaneous unaffiliated volunteers.

SOURCE: Tosatto presentation, March 26, 2014.

Spontaneous unaffiliated volunteers—people who show up to volunteer during an emergency without any preregistration or notification—can be the most problematic, noted Tosatto (see Figure 3). Emergency managers have to provide just-in-time training, rapid screening, background checks, and verification of credentials, and each jurisdiction may do this differently. Having a system in place for volunteer management is critical, said Tosatto.

To improve volunteer coordination in disaster preparedness and response, several participants explored promising practices for the management of volunteers during emergencies across a region.

“As a regional disaster happens,” Tosatto proposed, “and eventually it will, what are things we need to be concerned about, like coordination of volunteers between the many voluntary organizations, and how can they not only partner with each other, but how can they assist with the official response? What about things like competency, and how do you ensure that the people that are volunteering are competent? What about legal protections? How do you ensure that there are legal protections in place for the volunteers that you want to assist?”

- Create a standardized capabilities framework for medical and public health volunteer response agencies, voiced Hick. Given that there are no recognized definitions for voluntary organization capabilities in a public health and medical response, sharing volunteers across jurisdictions can be challenging. Several participants suggested defining a research agenda on capabilities and expectations and developing a pilot categorization tool to optimize use and sharing of volunteers across organizations.

- Developing a structure for management of spontaneous unaffiliated volunteers could improve use of volunteers during an event, was pointed out by Tosatto. Currently, there is no standardized method for managing spontaneous volunteers across organizations. Individual participants noted that by setting up a standard process of registering volunteers across organizations and allowing physical and virtual means of registration, prospective volunteers could be solicited across counties and integrated into existing volunteer databases. From here, their documented skillsets could be matched to the situational needs in different areas.

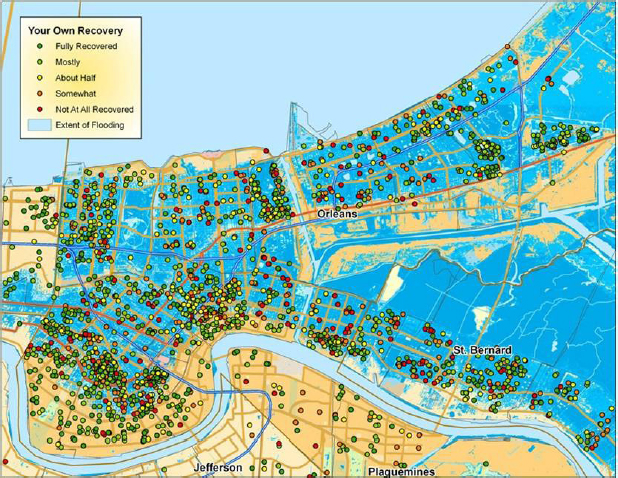

FIGURE 4 Perceived recovery after Hurricane Katrina (yellow and white areas are between 1 and 2 feet; darker blue areas are up to 13 feet of water).

SOURCE: Aldrich presentation, March 26, 2014.

Social Capital and Cohesion

“There’s no way of guaranteeing any bridge you build, any levee you build will hold, but these kind of social ties, in contrast, social infrastructure: this we know from experience and from data, this drives the resilience process.” —Daniel Aldrich

Social capital and cohesion is a concept that refers to the social networks, degree of connectedness, and a sense of belonging that residents feel within their community (e.g., knowing one’s neighbors; volunteering; participating in civic groups, school groups, churches, and other neighborhood organizations). Daniel Aldrich, Associate Professor of Political Science at Purdue University, discussed the importance of social capital and cohesion when it comes to regional disaster preparedness and recovery. Six months after Hurricane Katrina, he and a colleague conducted a house to house survey of 1,000 New Orleans residents to determine factors associated with rebuilding. He found that rebuilding was not correlated with less water depth (2 feet versus 15 feet), more resources (insurance and savings), lower population density (which offers more routes of evacuation), or fewer deaths. Instead, rebuilding occurred in clusters that were correlated to the residents’ social ties within the community (see Figure 4).

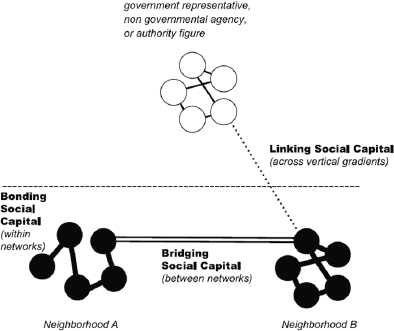

Based on subsequent research of four different disasters (1923 Tokyo earthquake, 1995 Kobe earthquake, 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, and 2005 Hurricane Katrina), Aldrich found that three types of social connections were associated with recovery and resilience (see Figure 5): Bonding social capital: cohesion within social networks, such as ethnicities and religions; Bridging social capital: linkages across different social networks through institutions, schools, and sports clubs, among other venues; and Linking social capital: connections between citizens and government and/or elected officials who hold positions of authority and power.

FIGURE 5 Theoretical approach to social capital and cohesion.

SOURCE: Aldrich presentation, March 26, 2014.

Several participants said that historically there has been a top-down approach to disaster recovery in which people relied on the system to rebuild their community, rather than seeing it as a shared responsibility. However, as evidenced by Aldrich’s data from Hurricane Katrina, having pockets of social capital in isolated neighborhoods may not contribute to the full recovery of a geographic region. While social capital efforts may need to start at a neighborhood level, where Aldrich noted that people can find similarities among their neighbors, connecting neighborhoods and communities across city, state, and tribal lines could help promote resiliency and recovery in states and larger regions.

During this discussion, individual speakers and participants highlighted important ideas to assist in creating more robust social capital and connecting communities across a region:

- Building ownership of resilience from within a neighborhood and community can foster community stewardship and strengthen capacity at the neighborhood level, several participants noted. Aldrich said flexibly engaging with neighborhoods toward shared goals is critical, creates a sense of empowerment at the community level, and strengthens ties within and outside the community.

- Creating an evidence base for community members was an idea emphasized by Kenneth Schor, Acting Director of the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health. An evidence base could serve to increase access to the best data available to inform academia, policymakers, and community organizers and augment community resilience on a larger scale. By mapping the methodology used in various cities, several participants said, neighborhood leaders can leverage successes of individual communities and build linkages across jurisdictions.

Workshop chair W. Craig Vanderwagen closed the meeting stating that when disaster strikes, social cohesion is what makes the difference. Combining social cohesion with robust volunteer management, inclusive planning for at-risk populations, and holistic community collaboration can contribute to more coordinated and streamlined public health responses in large-scale disasters. Regardless of how many communities may be affected, prior engagement across jurisdictions in a variety of disciplines is important to ensure community resilience, well-being, and population health of a region.![]()

Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events

Robert P. Kadlec (Co-Chair)

RPK Consulting, LLC, Alexandria, VA

Lynne R. Kidder (Co-Chair)

Consultant, Boulder, CO

Alex J. Adams

National Association of Chain Drug Stores, Alexandria, VA

Roy L. Alson

American College of Emergency Physicians, Winston-Salem, NC

Wyndolyn Bell

UnitedHealthcare, Atlanta, GA

David R. Bibo

The White House, Washington, DC

Kathryn Brinsfield

Office of Health Affairs, Department of Homeland Security, Washington, DC

CAPT. D. W. Chen

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, Department of Defense, Washington, DC

Susan Cooper

Regional Medical Center, Memphis, TN

Brooke Courtney

Office of Counterterrorism and Emerging Threats, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Washington, DC

Bruce Evans

National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, Upper Pine River Fire Protection District, Bayfield, CO

Julie L. Gerberding

Merck Vaccines, Merck & Co., Inc., West Point, PA

Lewis R. Goldfrank

New York University School of Medicine, New York

Dan Hanfling

INOVA Health System, Falls Church, VA

Jack Herrmann

National Association of County and City Health Officials, Washington, DC

James J. James

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, Onancock, VA

Paul E. Jarris

Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, Arlington, VA

Lisa G. Kaplowitz

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Ali S. Khan

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA

Michael G. Kurilla

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Washington, DC

Donald M. Lumpkins

Federal Emergency Management Agency, Department of Homeland Security, Washington, DC

Jayne Lux

National Business Group on Health, Washington, DC

Linda M. MacIntyre

American Red Cross, San Rafael, CA

Suzet M. McKinney

Chicago Department of Public Health, IL

Nicole McKoin

Target Corporation, Furlong, PA

Margaret M. McMahon

Emergency Nurses Association, Williamstown, NJ

Aubrey K. Miller

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD

Matthew Minson

Texas A&M University, College Station

Erin Mullen

Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, Washington, DC

John Osborn

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

Andrew T. Pavia

Infectious Disease Society of America, Salt Lake City, UT

Steven J. Phillips

National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD

Lewis J. Radonovich

Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC

Mary Riley

Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Kenneth W. Schor

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD

Roslyne Schulman

American Hospital Association, Washington, DC

Margaret Vanamringe

The Joint Commission, Washington, DC

W. Craig Vanderwagen

Martin, Blanck & Associates, Alexandria, VA

Jennifer Ward

Trauma Center Association of America, Las Cruces, NM

John M. Wiesman

Washington State Department of Health, Tumwater

Gamunu Wijetunge

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Washington, DC

DISCLAIMER: This workshop in brief has been prepared by Meghan Mott, Sheena Posey-Norris, and Megan Reeve, rapporteurs, as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the authors or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies.

This workshop in brief was reviewed by Dan Dodgen, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, and Kate Garay, Marin County Medical Reserve Corps; and coordinated by Erika Vijh, Institute of Medicine, to ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity.

This workshop was partially supported by the American College of Emergency Physicians; American Hospital Association; Association of State and Territorial Health Officials; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Department of Defense; Department of Defense, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; Department of Health and Human Services’ National Institutes of Health: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Environmental Sciences, National Library of Medicine; Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response; Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency; Department of Homeland Security, Office of Health Affairs; Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Department of Veterans Affairs; Emergency Nurses Association; Food and Drug Administration; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Martin, Blanck & Associates; Mayo Clinic; Merck Research Laboratories; National Association of Chain Drug Stores; National Association of County and City Health Officials; National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians; Pharmaceutical Research and Manufactures of America; Target Corporation; Trauma Center Association of America; and United Health Foundation.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit www.iom.edu/Activities/PublicHealth/MedPrep/2014-MAR-26.aspx.

Copyright 2014 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.